Reactive Ni–Al-Based Materials: Strength and Combustion Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

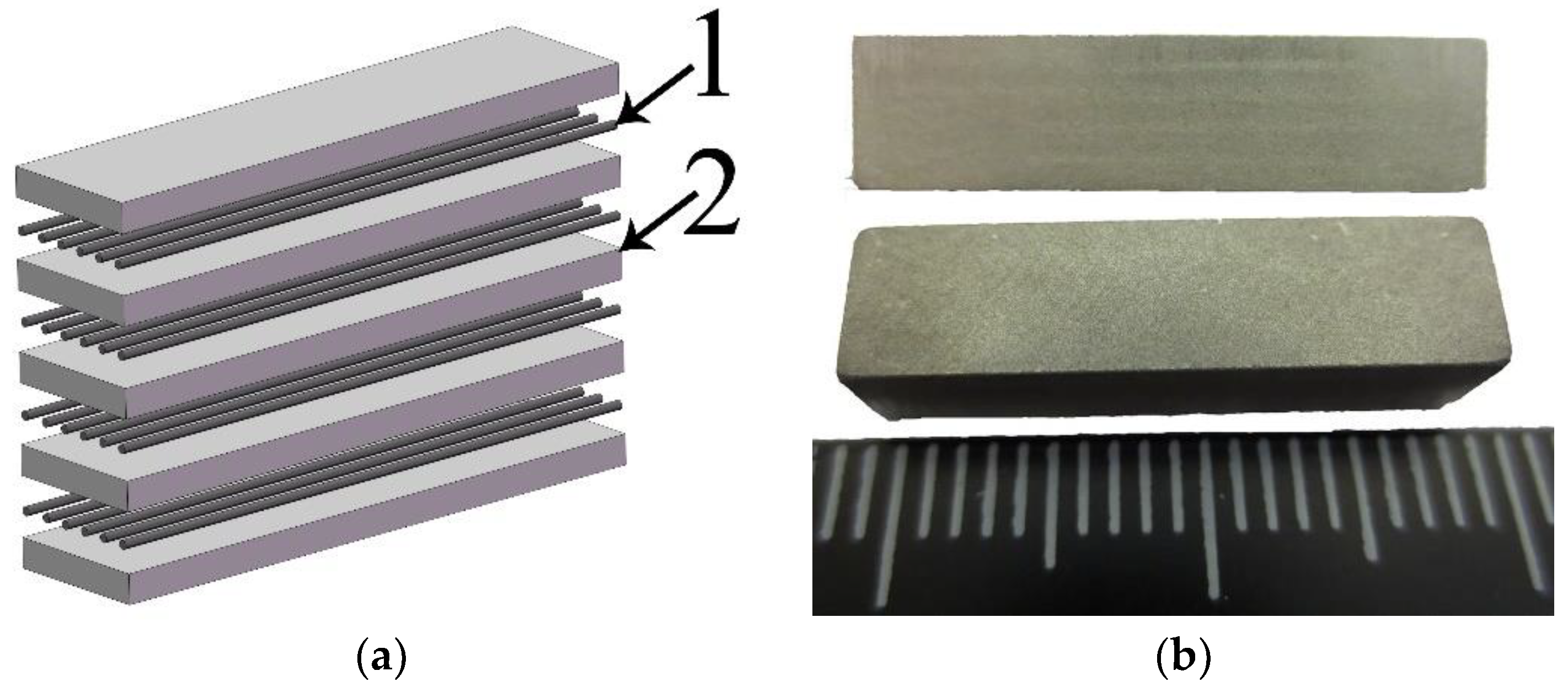

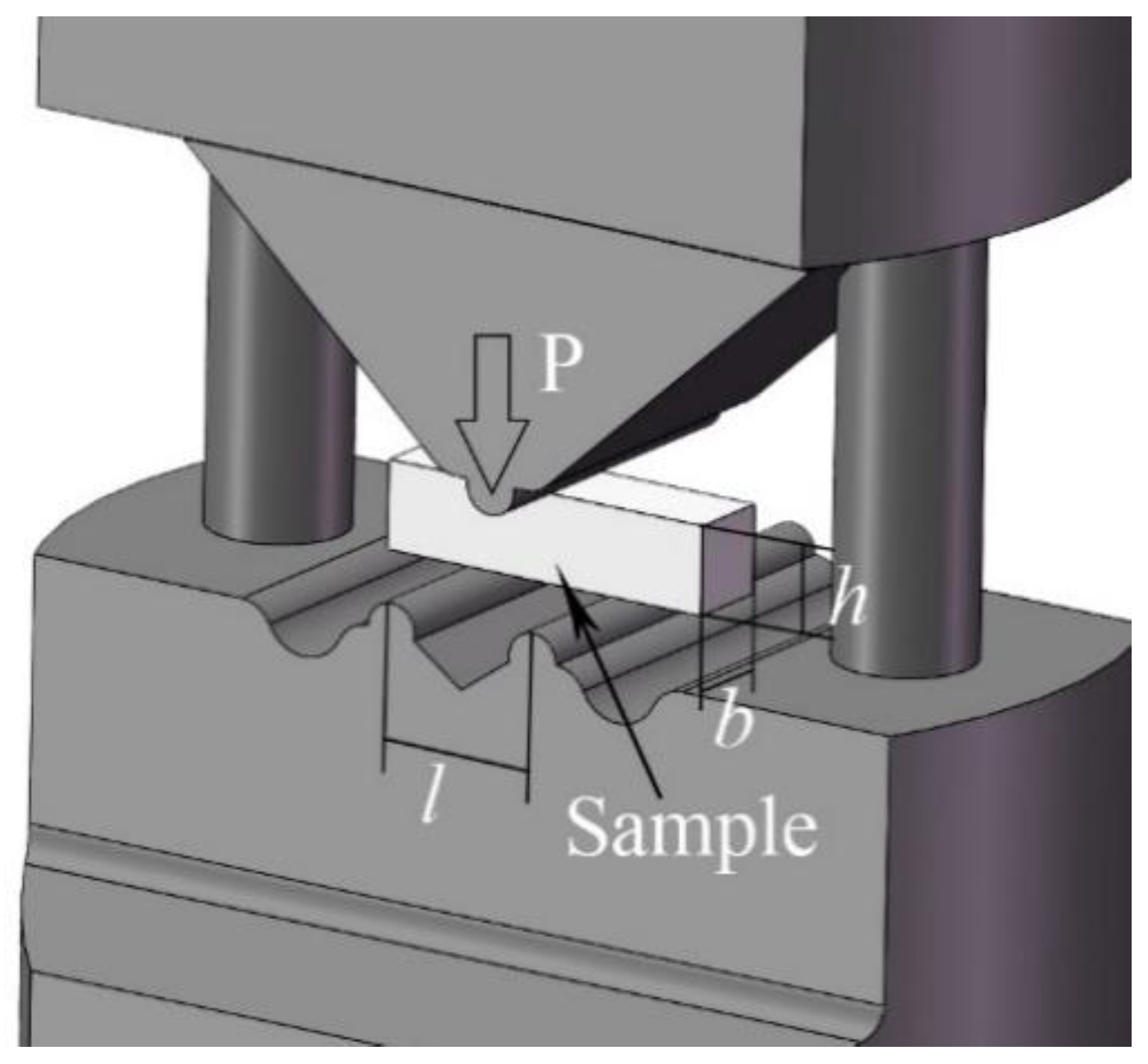

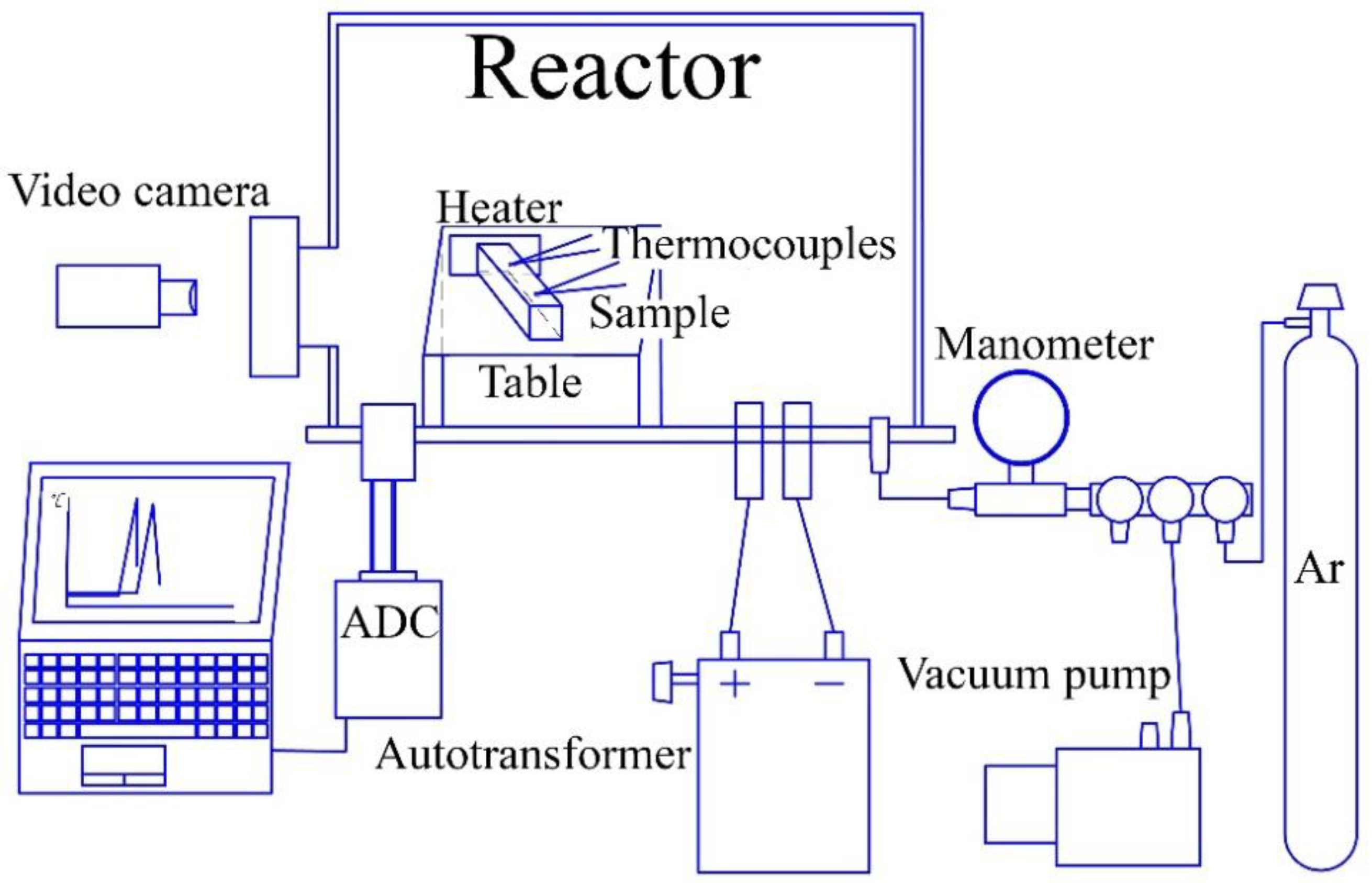

2. Materials and Methods

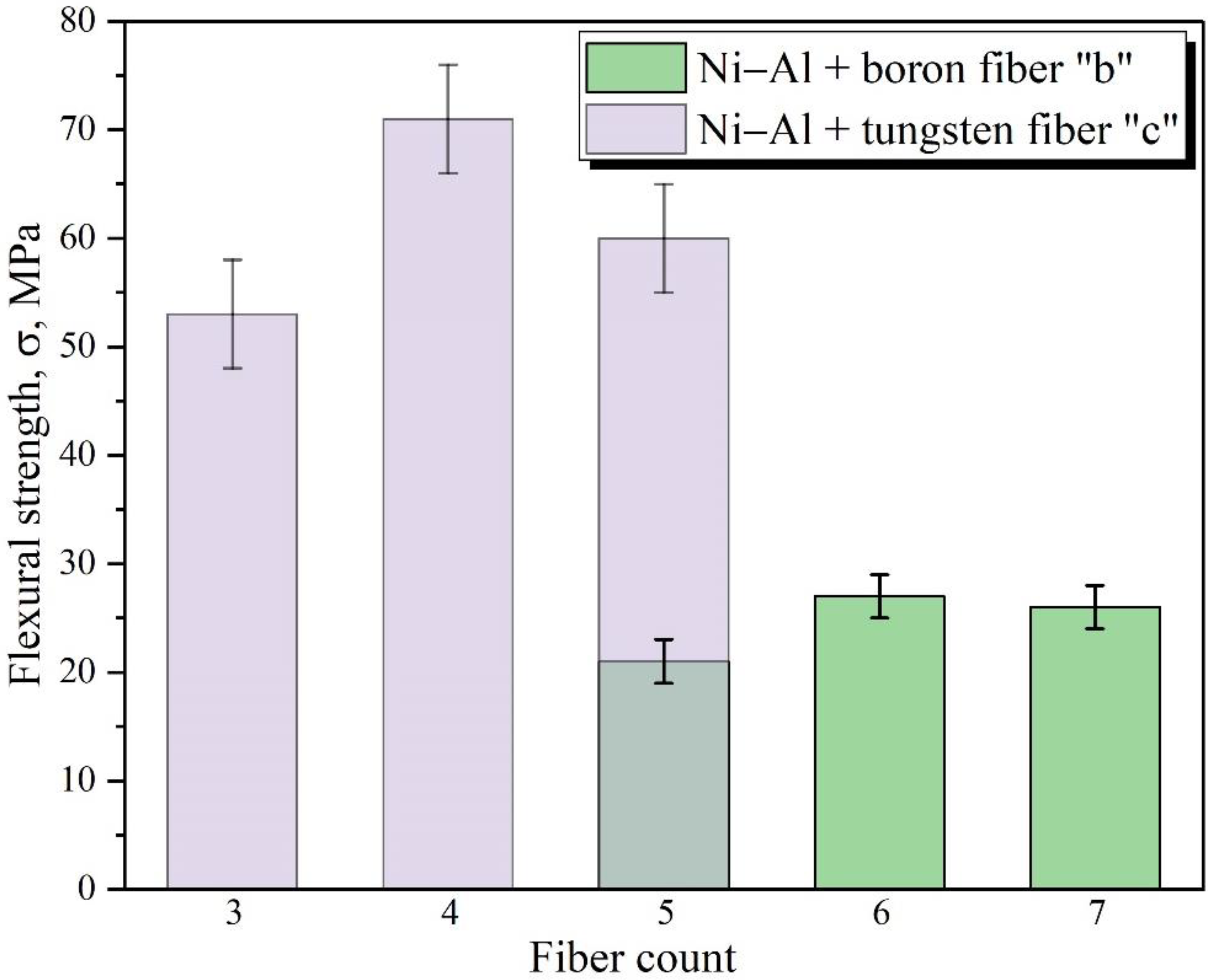

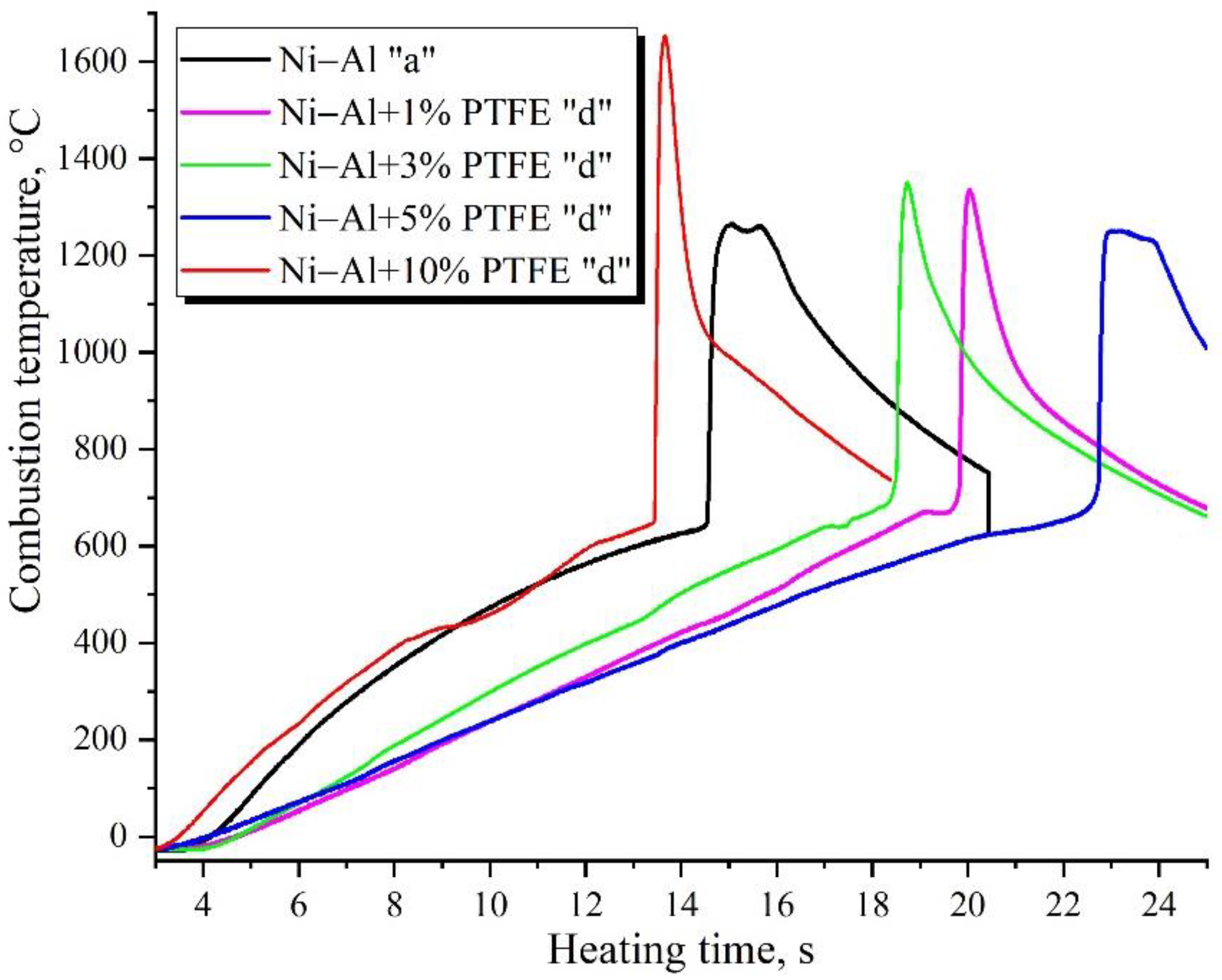

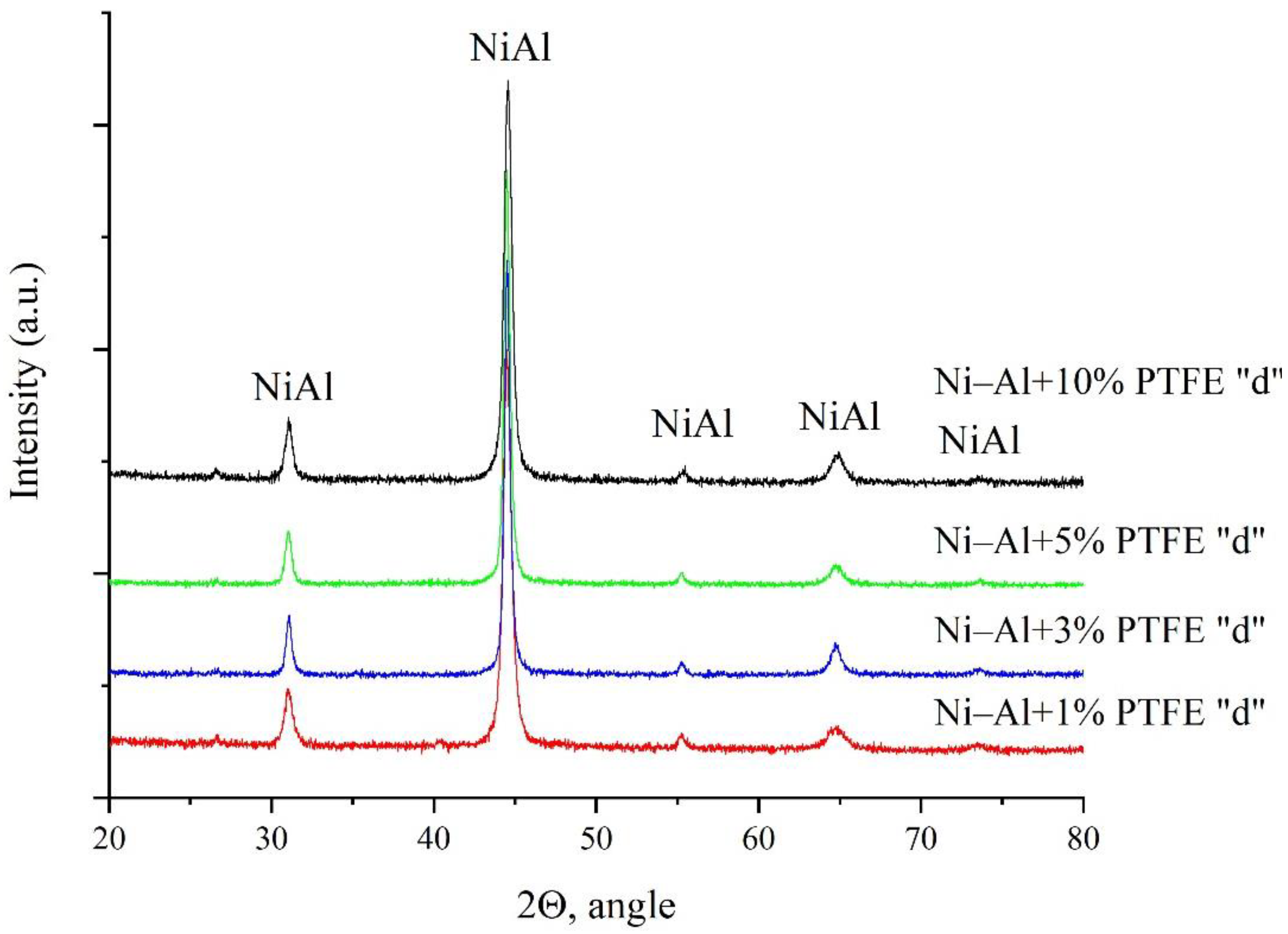

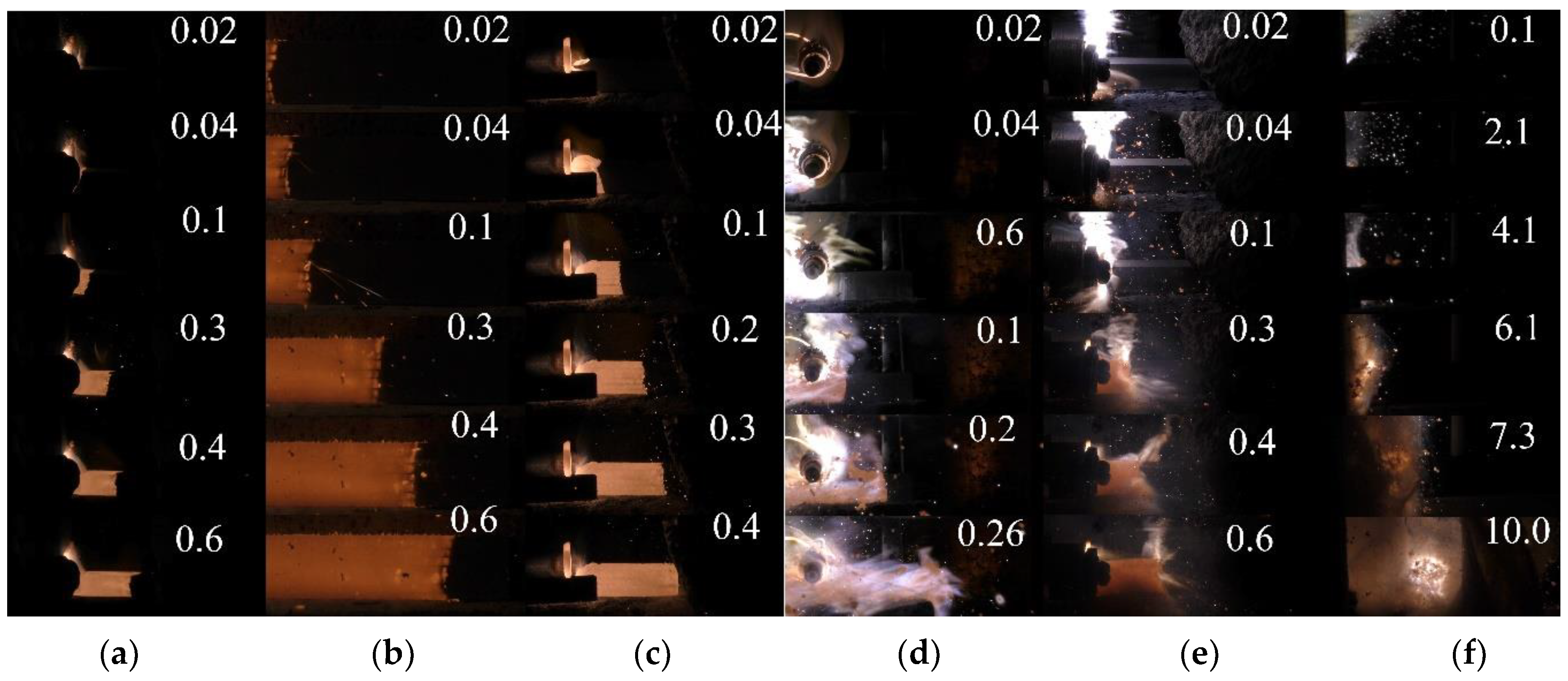

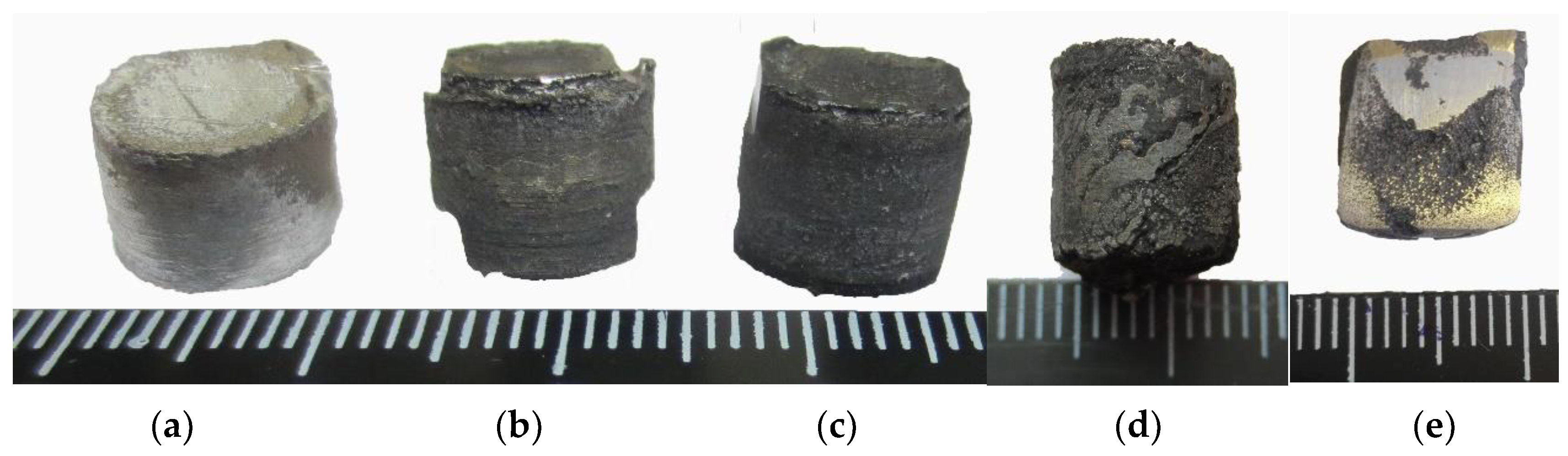

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hastings, D.L.; Dreizin, E.L. Reactive Structural Materials: Preparation and Characterization. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2017, 20, 1700631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Liu, P.-J.; He, G.-Q.; Gozin, M.; Yan, Q.-L. Highly Reactive Metastable Intermixed Composites (MICs): Preparation and Characterization. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1706293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Liu, X.; Ning, J. Impact-initiated behavior and reaction mechanism of W/Zr composites with SHPB setup. AIP Adv. 2016, 6, 115205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X.; Hu, X.; Liu, Y. Reactivity and Penetration Performance Ni–Al and Cu–Ni–Al Mixtures as Shaped Charge Liner Materials. Materials 2018, 11, 2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Hu, Q.W.; Wang, B.; Zhou, B.B.; Chen, P.W.; Liu, R. Fabrication and characterization of the Ni–Al energetic structural material with high energy density and mechanical properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 832, 154894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbins, J.D.; Stover, A.K.; Krywopusk, N.M.; Woll, K.; Weihs, T.P. Properties of reactive Al:Ni compacts fabricated by radial forging of elemental and alloy powders. Combust. Flame 2015, 162, 4408–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, P.-H.; Olney, K.L.; Benson, D.J.; Braithwaite, C.; Collins, A.; Nesterenko, V.F. Dynamic fragmentation of Al–W granular rings with different mesostructures. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 121, 045901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Mao, Z.; Weng, Z.; Wang, H.; Tao, J. Microstructure Evolution and Compressive Properties of Multilayered Al/Ni Energetic Structural Materials under Different Strain Rates. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renk, O.; Tkadletz, M.; Kostoglou, N.; Gunduz, I.E.; Fezzaa, K.; Sun, T.; Stark, A.; Doumanidis, C.C.; Eckert, J.; Pippan, R.; et al. Synthesis of bulk reactive Ni–Al composites using high pressure torsion. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 857, 157503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baras, F.; Turlo, V.; Politano, O.; Vadchenko, S.G.; Rogachev, A.S.; Mukasyan, A.S. SHS in Ni/Al nanofoils: A review of experiments and molecular dynamics simulations. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2018, 20, 1800091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Ning, X.; Tan, C.; Yu, X.; Nie, Z.; Sun, X.; Cui, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, F.; Cai, H. Influence of Al12Mg17 Additive on Performance of Cold-Sprayed Ni–Al Reactive Material. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2019, 28, 780–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ning, X.; Yu, X.; Tan, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, T.; Li, L.; Nie, Z.; Liu, Y. Energy Release Characteristics of Ni–Al–CuO Ternary Energetic Structural Material Processed by Cold Spraying. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2020, 29, 1070–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, S.; Izumi, T.; Yamamoto, R. Effect of the Particle Size of Al/Ni Multilayer Powder on the Exothermic Characterization. Materials 2020, 13, 4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Tan, C.; Yu, X.; Ning, X.; Nie, Z.; Cai, H.; Wang, F.; Cui, Y. Enhanced reactivity of Ni–Al reactive material formed by cold spraying combined with cold-pack rolling. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 741, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Fang, X.; Li, Y.; Mao, Y.; Yang, L.; Yin, Q.; Wu, S.; Yao, M.; Song, J. Investigation on shock-induced reaction characteristics of an Al/Ni composite processed via accumulative roll-bonding. Mater. Des. 2017, 116, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamenko, N.A.; Kazurov, A.V.; Agafonova, G.V.; Savin, D.V. Structure Formation in Nickel-Polytetrafluorethylene Composite Materials upon Explosive Pressing of Powders. Inorg. Mater. Appl. Res. 2020, 11, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Han, Y.; Guo, C.; Chang, Y.; Han, X.; Lan, L.; Jiang, F. Synthesis and mechanical properties of novel Ti–(SiCf/Al3Ti) ceramic-fiber-reinforced metal-intermetallic-laminated (CFR-MIL) composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 722, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, N.; Zhang, M. Fiber-reinforced geopolymer composites: A review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 107, 103498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, S.; Fan, M.; Rees, D.W.A. Bonding Mechanisms and Strength of Steel Fiber–Reinforced Cementitious Composites: Overview. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E.; Li, S.; Chen, C.; Han, Y. Dynamic compressive behavior of fiber reinforced Al/PTFE active materials. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 8391–8400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Nie, Z.; Wang, Z.; Du, Y.; Tang, E. Energy release behavior of Al/PTFE reactive materials powder in a closed chamber. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 127, 165106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Gao, R.; Guo, K.; He, L.; Chang, M.; Han, Y.; Tang, E. Thermoelectric behavior of Al/PTFE reactive materials induced by temperature gradient. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer. 2021, 123, 105203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkachev, V.F.; Ivanova, O.V.; Zelepugin, S.A. Initiation and development of exothermic reactions during solid-phase synthesis under explosive loading. Therm. Sci. 2019, 23, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelepugin, S.A.; Ivanova, O.V.; Yunoshev, A.S.; Zelepugin, A.S. Problems of Solid-Phase Synthesis in Cylindrical Ampoules under Explosive Loading. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 127, 012057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Dong, Y.X.; Maimaitituersun, W.; Ren, Y.M.; Feng, S.S. Experimental study on impact-induced initiation thresholds of Polytetrafluoroethylene/Aluminum composite. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2017, 42, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Tang, E.; Zhu, W.; Han, Y.; Gao, Q. Modified model of Al/PTFE projectile impact reaction energy release considering energy loss. Exp. Therm Fluid Sci. 2020, 116, 110132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Cai, S.; Mao, L.; Wang, Z. Effect of Porosity on Dynamic Mechanical Properties and Impact Response Characteristics of High Aluminum Content PTFE/Al Energetic Materials. Materials 2020, 13, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Qu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zheng, Y. On dynamic response and fracture-induced initiation characteristics of aluminum particle filled PTFE reactive material using hat-shaped specimens. Mater. Des. 2020, 188, 108472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Li, W.; Ning, J. Effect of temperature on the impact ignition behavior of the aluminum/polytetrafluoroethylene reactive material under multiple pulse loading. Mater. Des. 2020, 189, 108522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Fang, X.; Li, Y.C.; Wang, H.X.; Mao, Y.M.; Wu, S.Z. An Initiation Phenomenon of Al–PTFE under Quasi-Static Compression. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2015, 637, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Dong, Y.; Maimaitituersun, W. Microscale Simulation on Mechanical Properties of Al/PTFE Composite Based on Real Microstructures. Materials 2016, 9, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-X.; Fang, X.; Gao, Z.-R.; Wang, H.-X.; Huang, J.-Y.; Wu, S.-Z.; Li, Y.-C. Investigation on Mechanical Properties and Reaction Characteristics of Al–PTFE Composites with Different Al Particle Size. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.F.; Geng, B.Q.; Guo, H.G.; Zheng, Y.F.; Yu, Q.B.; Ge, C. The effect of sintering and cooling process on geometry distortion and mechanical properties transition of PTFE/Al reactive materials. Def. Technol. 2020, 16, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E.; Luo, H.; Han, Y.; Chen, C.; Chang, M.; Guo, K.; He, L. Experimental study on burning of two Al/PTFE samples. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 180, 115857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E.; He, Z.; Chen, C.; Han, Y. Characterization of dynamic compressive strength and impact release energy of Al/PTFE energetic materials reinforced by aluminum honeycomb skeleton. Compos. Struct. 2020, 241, 112063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Tang, E.; Ou, X.; Gao, X.; Jiang, L.; Chen, C.; Chang, M.; Han, Y. Energy release of Al/PTFE materials enhanced by aluminum honeycomb framework subjected to high speed impact under vacuum environment. Journal of Materials Research and Technology. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 14528–14539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valluri, S.K.; Schoenitz, M.; Dreizin, E.L. Metal-rich aluminum–polytetrafluoroethylene reactive composite powders prepared by mechanical milling at different temperatures. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 7452–7465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Tang, E.; Luo, H.; Han, Y.; Duan, Z.; Chang, M.; Guo, K.; He, L. Heat conduction and deflagration behavior of Al/PTFE induced by thermal shock wave under temperature gradient. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 118, 104834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Zhang, X.; Tan, M.; Liu, C.; Wu, X. The Energy Release Characteristics of Shock-Induced Chemical Reaction of Al/Ni Composites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 24551–24559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiryaev, A.A. Thermodynamics of SHS: Modern approach. Int. J. Self-Propag. High-Temp Synth. 1995, 4, 351–362. [Google Scholar]

- Alymov, M.I.; Vadchenko, S.G.; Saikov, I.V.; Kovalev, I.D. Shock-wave treatment of tungsten/fluoropolymer powder compositions. Inorg. Mater. Appl. Res. 2017, 8, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadchenko, S.G.; Alymov, M.I.; Saikov, I.V. Ignition of Some Powder Mixtures of Metals with Teflon. Inorg. Mater. Appl. Res. 2018, 9, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zeng, C.; Zhan, C.; Zhang, L. Tuning the reactivity and combustion characteristics of PTFE/Al through carbon nanotubes and grapheme. Thermochim. Acta 2019, 676, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaurav, M.; Ramakrishna, P.A. Effect of mechanical activation of high specific surface area with PTFE on composite solid propellants. Combust. Flame 2016, 166, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, W.; Fan, Z.; Liu, L.; An, Y.; Ren, J.; Zhao, M.; Liu, P.; Li, L.K.B. Agglomeration and combustion characteristics of solid composite propellants containing aluminum-based alloys. Combust. Flame 2020, 220, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, A. Interfaces in Metal Matrix Composites. In Composite Materials, 1st ed.; Metcalfe, A., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; Volume 1, pp. 64–126. [Google Scholar]

- Turlo, V.; Politano, O.; Baras, F. Alloying propagation in nanometric Ni/Al multilayers: A molecular dynamics study. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 121, 055304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beason, M.T.; Gunduz, I.E.; Son, S.F. The Role of Fracture in the Impact Initiation of Ni–Al Intermetallic Composite Reactives during Dynamic Loading. Acta Mater. 2017, 133, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, M.; Oh, M.C.; Han, D.; Jung, S.-H.; Ahn, B. Exothermic Reaction Kinetics in High Energy Density Al–Ni with Nanoscale Multilayers Synthesized by Cryomilling. Metals 2018, 8, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Rehwoldt, M.; Kline, D.J.; Wu, T.; Wang, P.; Zachariah, M.R. Comparison study of the ignition and combustion characteristics of directly-written Al/PVDF, Al/Viton and Al/THV composites. Combust. Flame 2019, 201, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

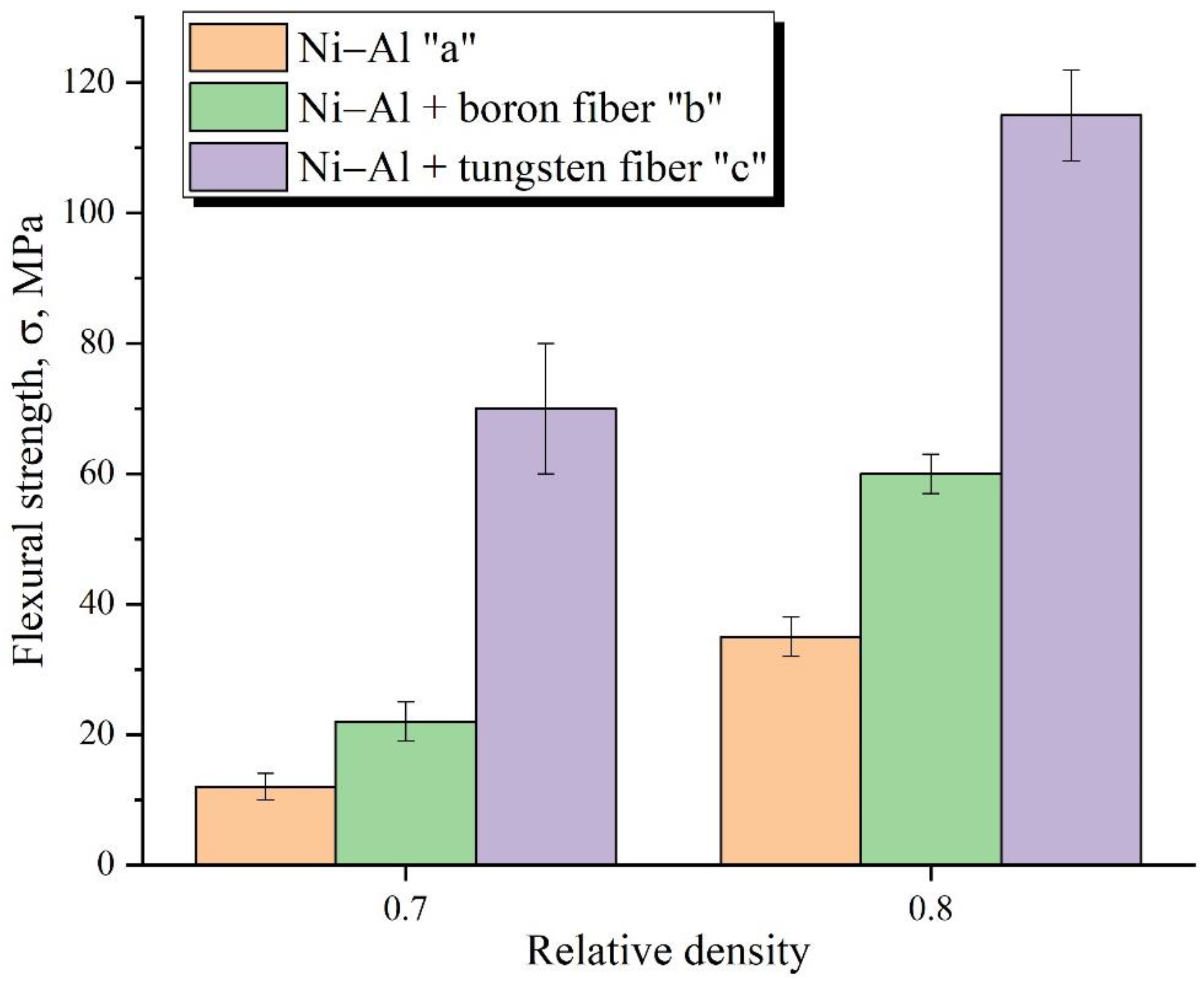

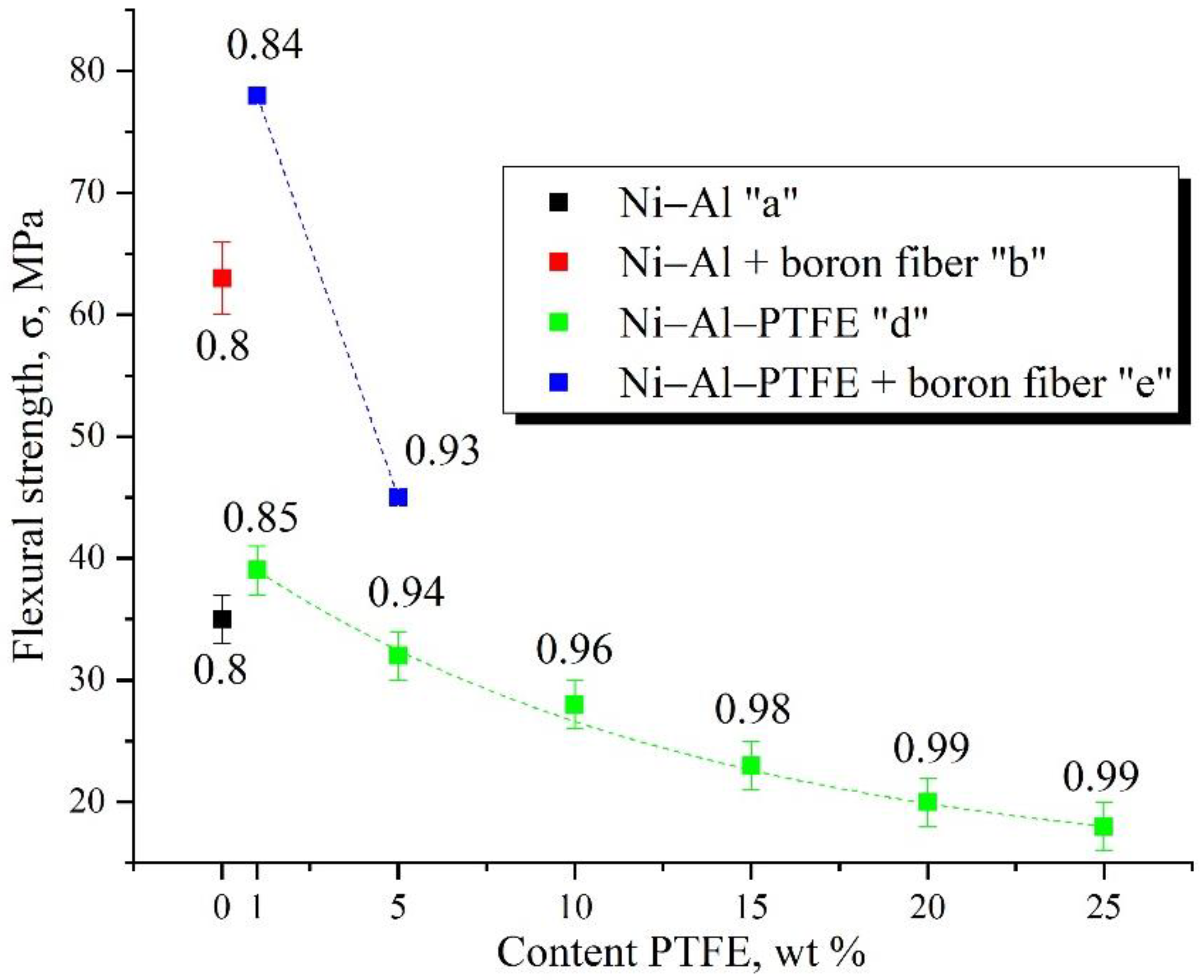

| Composition | Ni–Al | Ni–Al + Boron Fiber | Ni–Al + Tungsten Fiber | Ni–Al–PTFE | Ni–Al–PTFE + Boron Fiber |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of specimens | a | b | c | d | e |

| Relative density | 0.7; 0.8 | 0.7; 0.8 | 0.7; 0.8 | 0.84–0.99 * | 0.84–0.94 * |

| PTFE, wt % | – | – | – | 1; 3; 5; 10; 15; 20; 25 | 1; 3; 5 |

| Type of Specimens | a | a, b, c | a, b | a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holding Time, h | Temperature of Heating, °C | |||

| 1 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 550 |

| 2 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 550 |

| 3 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 550 |

| Temperature of Heating °C | 400 | 500 | 550 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holding Time, h | Temperature of Ignition, °C | ||

| 1 | 760 | 720 | 785 |

| 2 | 770 | 810 | 915 |

| 3 | 740 | 820 | 980 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seropyan, S.; Saikov, I.; Andreev, D.; Saikova, G.; Alymov, M. Reactive Ni–Al-Based Materials: Strength and Combustion Behavior. Metals 2021, 11, 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/met11060949

Seropyan S, Saikov I, Andreev D, Saikova G, Alymov M. Reactive Ni–Al-Based Materials: Strength and Combustion Behavior. Metals. 2021; 11(6):949. https://doi.org/10.3390/met11060949

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeropyan, Stepan, Ivan Saikov, Dmitrii Andreev, Gulnaz Saikova, and Mikhail Alymov. 2021. "Reactive Ni–Al-Based Materials: Strength and Combustion Behavior" Metals 11, no. 6: 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/met11060949

APA StyleSeropyan, S., Saikov, I., Andreev, D., Saikova, G., & Alymov, M. (2021). Reactive Ni–Al-Based Materials: Strength and Combustion Behavior. Metals, 11(6), 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/met11060949