Abstract

Little attention has been given to the processes and dynamics involved in community-engaged research with hard-to-reach and marginalized communities. This concept paper focuses on experiences with and lessons learned from the developmental phase of a community-engaged research project aimed at promoting the economic self-sufficiency of refugees with disabilities in Illinois. Steps taken to foster collaboration between academic researchers and community stakeholders are described, followed by the authors’ commentary on challenges encountered and how these were addressed. Several methods were used to facilitate engagement of community stakeholders. In the pre-funding stage, lead researchers identified potential community partners by networking with coalition groups and task forces focused on disability- and refugee-related issues. In the post-funding stage, relationships with partners were formalized, partners’ roles were defined, and contractual agreements were developed. An advisory board consisting of representatives from partner agencies and self-advocates with disabilities was also assembled to help guide the project goals and deliverables. Structured group and one-on-one meetings were held to sustain community partner engagement. These community engagement strategies were deemed successful. However, challenges did emerge due to conflict between community stakeholders’ preferences, and research logistics and regulatory requirements of the academic institution. Findings suggest that with careful planning, barriers to community-academic collaborations can be addressed in ways that benefit all parties. This paper offers practical strategies and a roadmap for other community-engaged research projects focusing on vulnerable and marginalized groups.

1. Introduction

By the end of 2016, a record number of more than 65 million people around the world were forcibly displaced from their homes and communities due to war or persecution [1]. These numbers included 20 million refugees and asylum seekers compelled to leave their countries of origin in search of stability and security elsewhere [1]. Many of these individuals have sought to build new lives in North America and Western Europe. In 2015 and 2016, more than 2.5 million people applied for asylum in European Union countries [2] while nearly 85,000 refugees were resettled in the United States (US) in fiscal year 2016 [3]. Although these numbers declined in 2017 due to political backlash, a steady flow of refugees and asylum seekers continues into North America and Western Europe [4]. Many of these individuals have disabilities, either as a result of preexisting conditions, due to injuries or trauma experienced before and during flight, or from injuries or conditions developed after resettlement [5]. Host countries struggle to accommodate refugee migrants with disabilities, and few models exist to support their integration into unfamiliar economic and social structures.

In this paper, we describe and reflect on the developmental phase of a community-engaged research project known as Partners of Refugees in Illinois Disability Employment (PRIDE). The project is funded by a three-year federal grant and was launched in September 2016 to improve the economic self-sufficiency of refugees with disabilities who have been resettled in the US state of Illinois. The project is currently in its second year with an anticipated goal of 50 refugees with disabilities served by the end of Year 3. Data collection on participant satisfaction, employment/career goals, and workforce outcomes is also underway. This paper focuses not so much on the results of the project, but more so on the process of developing and launching it. The information and reflective commentary presented are largely based on minutes and notes from project-related meetings and post-meeting debriefings between the three authors, who are the lead researchers for the project.

The objectives of this paper are to: (1) describe the context of the project; (2) discuss the project’s roots in community-engaged research and summarize unique aspects of PRIDE’s community-academic partnerships; (3) share development activities and strategies for community stakeholder engagement; and (4) reflect on the challenges of conducting community-engaged research with a large number of multi-sector partners and marginalized refugee communities.

2. Context of PRIDE

Historically, the US has had the largest refugee resettlement program worldwide, with nearly three million resettled since 1980 [6]. Admission of refugees into the US is based on processing priorities [3], and one important objective is to resettle the most vulnerable refugee populations, which includes those with physical injuries and psychological trauma [7]. Many refugees arrive with either pre-existing chronic health conditions, physical and mental disabilities, or a combination of these due to turbulent migration histories, war injuries, and associated traumas, while others may become disabled post-resettlement due to an accident, injury, and/or a secondary health condition. Illinois, where PRIDE is based, is among the top destination states in the US for refugee resettlement [6]. According to one report, an estimated 13% of refugees resettled in Illinois had a disability upon arrival [8].

Resettled refugees with disabilities generally find limited opportunities for integration into their host society [9]. Language barriers, cultural differences, and limited awareness of disability-related supports and resources all contribute to their social isolation and negatively impact their ability to thrive economically. Given that economic participation is an important way for refugees with and without disabilities to integrate into their host countries, resettlement programs in economically advanced nations emphasize learning local languages and acquiring viable job skills for resettled refugees [10].

Early employment and economic self-sufficiency for all newly-arrived refugees is a major focus of the US refugee resettlement program [11]. State and local non-profit agencies receive federal funding to provide reception services for refugees, such as transportation from the airport, housing assistance, and basic household supplies. These services are available for the first 90 days, after which refugees are expected to find paid employment or enroll in the social welfare system.

To help refugees find employment, US resettlement agencies also offer English-language training, as well as job search and job placement services during the first few months after resettlement [11]. Disability-related supports, such as wheelchair-accessible locations, sign language interpreters, or access to disability-related work incentives, are seldom accommodated within this support system [12]. Furthermore, service providers may perceive refugees with disabilities as unemployable and consequently channel them toward welfare assistance rather than encouraging them to pursue income-generating opportunities [9]. Refugees with disabilities may also be disconnected from mainstream support services [12]. For example, vocational rehabilitation (VR) constitutes a package of services available in every US state and territory to help people with disabilities prepare for, obtain, and maintain employment. Refugees are eligible for VR services upon arrival and/or at any time during resettlement or post-resettlement. However, our preliminary research indicates that refugees with disabilities in Illinois are seldom referred to VR services [13]. The combination of these circumstances places refugees with disabilities at a disadvantage and greatly hinders their economic participation, subjecting them to further isolation and marginalization.

3. PRIDE’s Roots in Community-Engaged Research and Unique Aspects of PRIDE’s Community-Academic Partnerships

PRIDE is an interdisciplinary project that uses a community-engaged research approach to build capacity among refugee service providers in order to promote employment and self-sufficiency among refugees with disabilities. Community-engaged research first emerged as a corrective to the insularity of the traditional research paradigm [14,15,16], which typically has been the domain of university-based scholars. The traditional approach to research is far removed from the everyday realities of individuals, families, and communities—the very people that social science research purports to benefit [17]. By contrast, a central component of community-engaged research is collaboration with all stakeholders associated with the problem under study: including individuals, families, service providers, educators, public officials, and policymakers. Each stakeholder is free to participate in the research process along a continuum, from partial to full engagement, according to availability, interests, and preferences [18].

Community-engaged research is especially well-suited to projects that involve isolated and marginalized groups, such as resettled refugees experiencing barriers to economic and social integration [19]. Several recent community-engaged research projects have focused on refugee communities in the US [20,21,22]. Published literature, however, tends to focus on the outcomes of such projects, while paying scant attention to the actual process of community engagement. According to experts in the field, the process of community engagement begins with building and sustaining community-academic partnerships [15,17]. If done right, partnerships between academic researchers and community stakeholders can provide a strong foundation on which to build community programs that are feasible and meaningful for target communities while also being amenable to rigorous research and evaluation [17]. Brookman-Frazee et al. proposed an iterative model to illustrate the processes and outcomes of developing community-academic partnerships based on their own experiences of creating a collaborative of transdisciplinary practitioners, funders, researchers, and families of children with autism spectrum disorders. The authors’ model calls for close attention to formative processes such as navigating the interpersonal and organizational processes that lie at the heart of community-academic partnerships [23].

A few recent studies have attempted to unpack the interpersonal and organizational processes involved in creating and sustaining community-academic partnerships. One large-scale study of 109 community-academic partnership projects identified several foundational attributes of successful partnerships. These attributes included: spending time on establishing trust and building relationships, developing strategic plans and creating advisory committees to oversee plans, making adjustments to plans given emerging insights and clarity about the project, regular and ongoing communication among partners, and consistent efforts to elicit community involvement during various stages of the project [24]. Overlapping findings emerged from a study involving 25 semi-structured interviews with community members who represented five community-academic partnerships. Key attributes of effective partnerships identified in this study included nurturing trusting relationships among partners, prioritizing community needs and preferences, clear division of roles and responsibilities, flexibility and compromise during project execution, and adequate resource allocation to partners [25].

In another study, eleven community stakeholders and researchers collaborating on an autism-focused project ranked the importance of factors essential for the formation of community-academic partnerships. Essential factors at the organizational level included strong leadership and well-structured meetings. At the interpersonal level, a shared vision for the goals and mission of the partnership, respect, and a good relationship among partners were identified as critical [26]. In a similar vein, Caldwell et al., writing from the perspectives of three long-time community partners, identified relationship building as the most important recommendation for academic researchers interested in community-engaged scholarship [27]. Ergo, researchers need to invest time and effort in building community relationships before planning community projects rather than rushing into partnerships after projects are funded.

Existing research has also identified several challenges associated with the functioning of community-academic partnerships. Some prominent challenges that can strain community-academic partnerships include inconsistent participation of members of the partnership [26], the need to adjust partnership plans due to shifting roles or replacement of members [24], excessive demands on community partners’ time [17], poor and/or inconsistent communication between community and academic partners [17], and funding periods that are insufficient for community partners to complete designated work [24,25]. Other sources of tension include differing points of view among community partners, differences between academic and community partners’ preferences for implementation, and misgivings that can emerge when scientific knowledge is privileged over experiential knowledge [28]. Partnerships can also become strained by administrative delays, such as delays in receiving authorization to pursue research activities from institutional review boards [24].

In summary, the existing literature identifies common facilitators and barriers in the process of developing and sustaining community-academic partnerships for community-engaged research. However, a contextual understanding of how these barriers are negotiated and addressed in relation to specific projects would provide greater insight into best practices. Thus, there is a need for detailed exposition of and critical reflection on the developmental phase of community-engaged research, both to demystify this approach for researchers unfamiliar with it, and to facilitate its continued use with refugees and other marginalized communities.

Table 1 summarizes unique aspects of PRIDE’s partnerships with community stakeholders. We chose specific strategies to address common facilitators of and barriers to community engagement in research, as identified in one of the most recent and comprehensive systematic reviews on this topic [17]. The following sections further describe PRIDE’s development activities and strategies for community stakeholder engagement.

Table 1.

Community engagement strategies, barriers, and facilitators.

4. PRIDE’s Development Activities and Strategies for Community Stakeholder Engagement

4.1. Engaging Community Partners Before Seeking Funding

This section describes efforts made by PRIDE’s lead researchers to engage community partners even before the project was conceived. An important first step in community-engaged research is to establish relationships between academic researchers and community-based partners that allow all stakeholders to collaboratively identify pressing issues affecting the target population and to work together to secure funding for an agreed-upon project [27,29].

For PRIDE, a critical first step was to identify community stakeholders who had been refugees themselves and/or were known to support refugee-related causes. For some projects, it is easy to define community stakeholders because they are affiliated with a single group with whom the academic researchers can partner (e.g., religious bodies, civil/human rights groups, or social organizations). For other projects, it is difficult to identify community partners because no single structured group exists that includes all types of stakeholders [30]. In the latter situation, academic researchers must partner with multiple individuals and organizations to ensure that the widest possible range of potential stakeholders are represented in the community-academic partnership.

The latter situation applied to PRIDE because no existing Illinois-based coalition or alliance brought together stakeholders concerned with economic self-sufficiency of refugees with disabilities. Therefore, in 2007, PRIDE’s lead researchers took the initial steps of reaching out to multiple local organizations that served refugees and/or people with disabilities. They also joined several coalition groups and task forces pertaining to disability- and refugee-related issues. These actions enabled the researchers to develop short-term and long-term relationships with a wide range of community-based organizations (CBOs) that serve refugees, as well as city and state agencies, civil and disability rights groups, and workforce and vocational networks (e.g., workforce centers, employers, and local chambers of commerce). These connections allowed PRIDE researchers to gain insights into the various barriers and opportunities encountered by refugees with disabilities as they attempt to integrate into American life.

Through targeted dialogues with stakeholders, we learned that existing refugee- and disability-focused employment programs were not meeting the needs of refugees with disabilities. For example, we found little to no evidence of efforts to make refugee-focused programs accessible through use of resources such as large print materials, sign language interpreters, and wheelchair-accessible locations [12]. We also found that few working-age refugees with disabilities had participated in disability-focused employment support services and programs available through the state Division of Rehabilitation Services [13]; in fact, most were unaware that work was a viable option for people with disabilities in the US. Thus, it was evident that any effort to support the economic self-sufficiency of refugees with disabilities would require a multifaceted, holistic approach that would bridge gaps among fragmented service systems while also leveraging existing resources and social capital within multicultural communities.

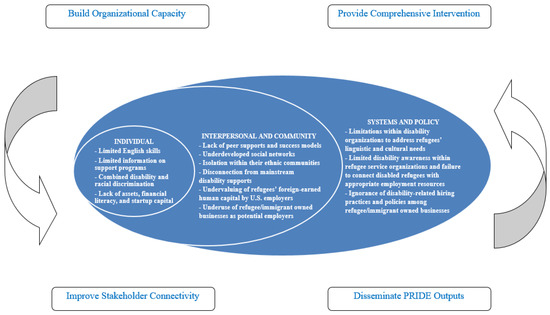

In the third quarter of 2012, PRIDE’s lead researchers formally invited the numerous community organizations we had been networking with since 2007 to collectively create a project proposal to develop employment initiatives for refugees with disabilities in Illinois. Over a series of meetings, PRIDE researchers and community partners collaborated to identify risk factors, as well as protective factors at the individual, family, community, organizational, and systems levels, which could affect employment and career opportunities for refugees with disabilities. We used this information to design a conceptual framework (Figure 1) for a comprehensive employment support program that could benefit this target population. PRIDE’s conceptual framework was informed by the social ecological model of human development [31]. We specifically chose and adapted this framework to reflect how employment opportunities for refugees with disabilities are influenced by the interplay between a multitude of factors operating at the individual, interpersonal and community, and systems and policy levels. The framework also serves as a reminder that PRIDE’s efforts need to address all of these levels for any meaningful impact on refugees with disabilities.

Figure 1.

PRIDE’s conceptual framework based on the social ecological model of human development.

We submitted our first grant proposal to secure funding for PRIDE in the second quarter of 2013. This attempt was unsuccessful, as was another submission to a different funder in the second quarter of 2014. However, we received helpful feedback which suggested that our original proposal listed too many community partners without explicitly defining their roles in the project as unique and supportive of the project goals. Reviewers also pointed out the need for stronger connections with potential employers and businesses that had a history of hiring people with disabilities. A third critique indicated a lack of clarity about how program materials would be made culturally- and linguistically-accessible for multiple ethnic groups.

After these critiques were duly noted and discussed with community partners, the original proposal was modified to highlight PRIDE’s core community partners. We listed all other community stakeholders as collaborators. Each core partner (defined below) then provided a support letter that highlighted its unique contribution to the project. The revised proposal was submitted in the first quarter of 2016 and was funded the same year.

4.2. Defining Stakeholder Roles and Expectations

This section outlines efforts made to define and clarify roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders involved in PRIDE. For community-academic partnerships to be successful, it is important to implement an organizational structure in which roles and expectations for community partners are clearly defined [17,25]. PRIDE works with three groups of community partners: core, primary, and complementary partners.

Core partners are defined as agencies whose staff work closely with PRIDE’s research team to provide direct employment-focused services to refugees with disabilities. Direct services include case management, employment counseling, job training and placement, assistive technology supports and workplace accommodations, and linkage to public benefits. PRIDE has six core partners: (1) the Division of Rehabilitation Services (DRS), the state’s lead agency that provides a range of vocational rehabilitation services related to employment, education, and independent living opportunities for people with disabilities; (2) the Social Security Administration, the federal agency that operates one of the most vital social insurance programs as well as provides work incentives for employment-seeking people with disabilities; (3) the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities, a local agency that promotes equal opportunity for people with disabilities through systemic change, education and training, advocacy, and direct services; (4) a provider of commercially-available, modified, and custom-designed assistive technology to help maximize the independence of people with disabilities; and (5, 6) two community rehabilitation agencies that specialize in providing employment services for refugees and immigrants.

PRIDE is also supported by more than ten primary partners. These include refugee service organizations, disability service organizations, technical assistance centers, employers and chambers of commerce, experts in mass media and broadcasting, and non-profit organizations and university-based programs that promote small businesses development in underserved communities. Primary partners are defined as agencies committed to providing PRIDE’s research team with technical or programmatic support. For example, the Great Lakes ADA Center is a primary partner that offers technical assistance to ensure that PRIDE’s activities and products comply with regulations established by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a federal law that prohibits discrimination based on disability. Similarly, the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University provides technical assistance with the development of promotional videos that feature testimonials from PRIDE participants and highlight employment success stories. Another primary partner is Accion Chicago, a non-profit organization that assists PRIDE’s research team with the development of programmatic tools to help refugees with disabilities establish small businesses.

Finally, PRIDE also derives support from more than 30 complementary partners. These fall into two main categories. One category includes agencies that provide guidance to make PRIDE’s products culturally-relevant and linguistically-accessible. The other category includes agencies that help PRIDE connect with refugee communities, businesses, potential employers, and employment-related resources.

A complete list of PRIDE’s community partners and their defined roles can be found on the project website [32]. We obtained written permission from partner agencies before publishing their names and logos under the designated categories (i.e., core, primary, and complementary). In addition, we developed an official contractual agreement with each core and primary partner that delineates the scope of work and expected deliverables along with associated timelines. Some agencies received a portion of PRIDE’s funding to build the capacity of service providers/agency staff to better support refugees with disabilities, as well as offset expenses (e.g., personnel hours, printing costs) incurred from PRIDE-related activities. This was a critical step as allocation of adequate resources to community partners is considered a key attribute of successful community-academic partnerships [25].

We took the above steps to prevent several possible threats to our community-academic partnerships. First, we wished to avoid misunderstandings about expectations between PRIDE’s community partners and the academic institution hosting PRIDE. Second, explicit agreements made each agency’s involvement in PRIDE transparent in order to prevent competition and mistrust among partners. Third, public statements about each partner’s respective role within PRIDE made it clear that all are involved in PRIDE to varying extents in order to avoid ill will that could arise if some agencies were seen as “lesser” participants.

4.3. Stakeholder Engagement during Development Activities

The literature on community-engaged research recommends that academic researchers make consistent efforts to engage community members during various stages of the project [15,24]. This section describes steps undertaken to promote stakeholder engagement during PRIDE’s developmental phase.

The cornerstone of any community-engaged project is a strong sense of trust between academic researchers and community stakeholders. Developing a shared vision for a project and how it will be executed is a key facilitator of trust [17,26]. To this end, we assembled a PRIDE advisory board that includes representatives from partner agencies as well as independent disability self-advocates. The advisory board was entrusted with the task of providing structured advice to guide the development and execution of PRIDE’s activities.

Three months after PRIDE was funded, the research team organized the first advisory board meeting. One of our core partners, DRS, hosted the meeting at one of its office locations as a means of introducing refugee agency representatives to the disability-focused services it provides. Fifty community stakeholders attended. In keeping with recommendations from the literature [17], we structured the meeting to both facilitate productivity and create opportunities for interactive dialogue.

For example, after an introductory presentation about the project, attendees participated in one of five brainstorming breakout groups. Each group was assigned a topic corresponding to one of PRIDE’s five objectives: (1) developing and implementing a culturally- and linguistically-appropriate employment-focused training curriculum and a comprehensive vocational assessment inventory for refugees with disabilities; (2) developing and implementing a training curriculum to foster disability awareness among refugee service providers; (3) creating an information technology tool to connect refugees with vocational supports and potential employers; (4) developing resources to facilitate small business opportunities for refugees with disabilities; and (5) assembling a network of employers willing to hire and train job-seeking refugees with disabilities. Members of PRIDE’s research team paired up with community partners to serve as facilitators and note-takers at each station.

Each brainstorming station was tasked with answering a list of guiding questions specific to the assigned topic, such as: What is already happening in this area? What is working or is not working? What content should be included in training curricula? What format should be used for trainings (i.e., individual, group, in-person, online, or mixed)? How can small business loans be arranged for refugees interested in self-employment or entrepreneurship? What existing information technology applications can serve as a template for PRIDE’s technology tool? What would be the best outreach method to connect with employers?

This process provided a structured format for community stakeholders to endorse and refine PRIDE’s main objectives. By the end, all five objectives had been unanimously validated, and PRIDE’s research team had a set of cohesive ideas for achieving a unified mission. It was also decided that the initial advisory board would be split into a community task force and a business task force. The community task force took on the responsibility of guiding the development and execution of PRIDE’s first three objectives, and the business task force agreed to oversee the latter two.

Stakeholder engagement did not end with the advisory board and task force meetings, however. Given that the literature highlights poor and inconsistent communication between researchers and community stakeholders as a major hindrance to community-academic partnerships [17], PRIDE’s research team initiated separate meetings with partner agencies in order to keep the lines of communication open. Site visits and/or conference calls were conducted with six refugee service agencies, six disability service agencies, four business partners, and two employment support agencies. These occurred at times and locations that were most convenient for community partners. The majority of PRIDE’s community partners are non-profit organizations that operate with tight operating budgets and limited staffing, so staff time is at a premium. In recognition of these exigencies, before each meeting or conference call we prepared and circulated an agenda with input from community partners so they had advance notice of the time and personnel commitments required.

Well-structured meetings are considered a cornerstone for smooth functioning of community-academic partnerships [26]. Therefore, each meeting was conducted using a set of guiding questions about the participating agency’s existing infrastructure and core activities, characteristics of its client base and eligibility criteria, the possibility of PRIDE’s activities being integrated into existing employment programs, and the types of support the agency could realistically contribute to PRIDE (e.g., assisting with recruitment of refugee participants; sharing data collection forms and employment training curricula, if available; providing meeting space for training participants; or releasing bilingual staff from other responsibilities to serve as interpreters and translators for PRIDE’s activities).

4.4. Respecting and Responding to Stakeholder Preferences

The prioritization of community needs and preferences is considered to be a key attribute of successful community-academic partnerships [25]. This section describes how PRIDE’s activities and deliverables were carefully planned in accordance with community needs and stakeholder preferences. Fortified with information from the first advisory board meeting and subsequent site visits, PRIDE’s research team set out to develop materials related to the project’s first three objectives as listed in the previous section: a training curriculum and vocational assessment inventory (VAI) for refugees with disabilities (objective 1), training modules for refugee service providers and peer mentors (objective 2), and an informational technology tool to facilitate referral and tracking of refugee participants to employment supports and services (objective 3). All of these materials were developed in accordance with stakeholder preferences, on-going feedback, and input sessions.

For example, the VAI incorporated questions from medical case management forms and employment intake forms routinely used at some of PRIIDE’s partner agencies in order to create a screening process already familiar to refugee participants. As another example of responding to stakeholder preferences, the provider and peer mentor training had originally been conceived as a two-day in-person event; however, community stakeholders overwhelmingly agreed that the provider training should be made available in a format that would allow each provider to complete it at their convenience. Accordingly, we developed the training as a series of narrated and captioned slide shows, approximately 15 to 40 min long, and offered in multiple accessible formats. The slide shows focus on a number of high-priority disability and employment topics and are hosted on a virtual learning platform that can be accessed from any web-enabled device using a unique username and password.

PRIDE’s information technology tool was similarly designed in response to stakeholder requests for a user-friendly interface. As originally planned, the tool was heavily text-based. Its current iteration, however, includes a visual dashboard for quicker and easier tracking of PRIDE participants’ progress along their journeys toward employment.

Once the preliminary versions of these materials had been developed, we convened a second meeting with a formal agenda and guiding discussion questions. Twelve members of the community task force attended this meeting. The purpose of the meeting was for PRIDE’s research team to share summaries and templates of materials developed and to solicit feedback about them. This second meeting also served as an opportunity to consult community stakeholders about logistics, such as locations of refugee trainings, cultural and linguistic adaptation of training materials for non-English-speaking refugees, and strategies for initiating conversations about disability (a potentially taboo topic) with providers, refugee communities, PRIDE’s refugee participants, and their families.

Several important decisions were made at this meeting. One decision was to host refugee trainings at community agencies that refugee participants were most familiar with and that could be easily accessed via public transportation. Another was to offer the trainings to groups of five to twelve refugee participants. Community stakeholders and the research team also agreed that the composition of each group should be defined not by the refugee participants’ ethnicities or nationalities but by their preferred language. For example, one training would bring together Arabic-speaking refugees from Syria, Iraq, and other Middle Eastern and African countries; another would include French-speaking refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Burundi; and so on. Community stakeholders assured the research team that organizing groups by preferred language would facilitate translation of materials and scheduling of interpreters. Community stakeholders also advised the research team to develop a script to initiate a conversation about disability with refugee participants. Stakeholders also suggested that the script should include a fact sheet listing myths and realities related to disability and employment. Since the term ‘disability’ does not have equivalent and/or respectful parallels in all languages, the research team was advised to avoid using this word in recruitment and outreach materials in favor of neutral, deliberately vague terminology, such as “health condition”.

Collectively, the above activities ensured a systematic and iterative process for stakeholder engagement through all of PRIDE’s development activities.

5. Challenges Encountered and Addressed

We encountered several unanticipated challenges during PRIDE’s developmental phase. First, the project was funded around the same time as the 2016 US presidential election, when a new president was elected. Unlike previous administrations, the new one held an unfavorable view of refugee resettlement. In fact, PRIDE’s initial advisory board meeting occurred on the same day that the new president signed an executive order that barred entry for 120 days of all refugees from anywhere in the world and placed an indefinite ban on Syrian refugees [33]. This order and its aftermath triggered such anxiety among PRIDE’s community stakeholders that advisory board members at the meeting described PRIDE as “the one wave of positivity in a sea of negativity”.

However, this enthusiasm also fueled a desire for PRIDE’s services to be made available more rapidly than could be managed considering the demands of university-affiliated research projects. A few partner agencies began referring refugee participants for PRIDE services before the research team was ready with contracts and approvals. For example, institutional bureaucracy delayed the development of contractual agreements with some core partners. The process for obtaining approval from the university’s institutional review board that oversees human subjects research ethics was long and arduous as well. As a result, the initial referrals to PRIDE had to be put on hold. Out of concern that these unavoidable, but frustrating, delays would cause disillusionment among community stakeholders, the lead researchers made special efforts to keep everyone apprised of changes in the project’s timeline and to explain the reasons for various delays. Regular updates were given at bi-monthly meetings of the Illinois Refugee Health Task Force, a statewide coalition of refugee-serving agencies and during ongoing in-person and/or phone meetings with community partners. Ultimately, these meetings provided opportunities to highlight PRIDE’s progress and thereby maintain stakeholders’ support for the project.

Discrepancies between community stakeholders’ preferences and the realities of the internal workings of academic institutions raised additional challenges. For example, institutional review boards require that project participants provide written consent before enrollment. Some of PRIDE’s community stakeholders, specifically refugee service providers and refugee community leaders, supported the idea of informed consent in principle but were wary of legal and social risks that could be incurred by refugees who signed consent forms. If confidentiality were to be breached, a signed consent document could be linked to a participant’s identity and reveal their status as a refugee. Such breaches could have grave consequences for refugee participants in an increasingly hostile political environment. This concern was amplified by the prospect of refugee participants consenting to be recorded for video testimonials of their employment journeys (including successes, as well as challenges) via the PRIDE program. As originally developed, the informed consent form included a checkbox for participants to consent to video recording. However, a single sentence within a four-page consent document was deemed insufficient to indicate an informed decision about being featured in a video that would be widely disseminated.

PRIDE’s research team addressed the above concerns in two ways. First, the statement about video recording was deleted from the main consent document and was expanded as a separate one-page video recording and photo release form. This form included specific details about the purpose of recording video footage, how footage would be used to develop video testimonials, and where and how videos would be disseminated. Separating this form makes it clear to potential participants that video and photo consent is optional and provides detailed information about what they are consenting to. In addition, PRIDE’s research team sought a Certificate of Confidentiality from the US National Institutes of Health. This is a legal document that protects the privacy of research participants by prohibiting disclosure of identifiable, sensitive research information to anyone not directly involved in the research. These strategies enabled PRIDE’s research team to allay community stakeholders’ concerns while also satisfying institutional expectations.

A few logistical challenges related to recruitment and data collection also arose. For example, the original plan for recruitment of refugee participants involved frontline staff at selected partner agencies. Designated staff members at each refugee-serving agency were to identify individuals from their client roster who would be suitable candidates for PRIDE. Agency staff would then reach out to potential participants, inform them about PRIDE, screen them for eligibility, and help them (if necessary) to complete the informed consent process. However, in order to assist with recruitment, screening, and consent procedures, staff at partner agencies would have been required to complete an intensive and time-consuming training in research ethics. This was a mandatory and non-negotiable condition stated by the institutional review board at the academic institution hosting PRIDE.

Knowing that partner agencies were already short-staffed, we reduced their participation in the recruitment process to dissemination of printed flyers (translated into multiple target languages) at PRIDE’s partner agencies. The flyers featured a brief description of PRIDE, outlined eligibility criteria for refugee participants, and included a contact form for interested refugees to indicate their consent to being contacted by PRIDE’s research team. Flyers could be posted on bulletin boards, placed at reception desks, or simply handed to refugee clients at partner agencies. Each partner agency received a lockbox with a secure lock into which interested individuals could deposit their completed contact forms. A member of PRIDE’s research team visited each agency to pick up contact forms, place them in a sealed envelope, and transport them to the academic institution. A member of the research team then contacted interested individuals by phone (aided by an interpreter if needed) to schedule a meeting for completion of eligibility screening and informed consent procedures. This recruitment process minimized the burden on agency staff and also ensured the security of recruitment and screening data.

Another logistical challenge related to the collection of VAI data from refugee participants. The VAI developed for PRIDE includes five questionnaires. Given the large amounts of data involved, the research team wanted to increase efficiency by entering data in real time, as assessments were being administered. In other words, assessment results would be entered directly into a secure database instead of using hard copies of forms first and entering data afterward. Real-time data entry, however, would have required refugee participants to travel to the academic site, where PRIDE’s secure database is hosted and to complete all assessments there. Community stakeholders were concerned about this arrangement and recommended that all assessments be conducted at community sites at which refugee participants would be most comfortable. The ensuing dilemma was resolved by using REDCap, a free web-based application that allows secure data collection and complies with federal regulations related to protection of sensitive information gathered from research participants [34]. A REDCap database was developed for PRIDE using data input fields derived from items in the VAI. Members of PRIDE’s research team can access this web-based secure database from any location, which means they can conduct assessments at community sites and input data in real-time. Thus, we devised a solution that met the needs of the research team and accommodated the preferences of community stakeholders.

PRIDE’s VAI is another example of how to keep community stakeholder needs at the forefront. The inventory includes self-reported work histories, work interests, job preferences, and functional abilities. We undertook a comprehensive review of VR literature before deciding which assessments to include in PRIDE’s inventory. Twenty-five assessments were considered for inclusion and appraised for relevance as well as feasibility. For each, the following information was compiled: target population, mode of administration, number of items and time required for administration, need for administrator training and expertise, available translations in other languages, and associated costs. PRIDE’s research team appraised each assessment for relevance and feasibility of use. One important criterion for determining whether an assessment would be included in the final inventory was if it could be administered by someone without any specific clinical training or expertise such as partner agency staff with various backgrounds and roles. Cost of the assessment was an additional important criterion given partner agencies’ limited budgets. At all times PRIDE staff gave priority to criteria that would ensure sustained use of assessments by partner agencies after completion of the PRIDE project.

6. Discussion

In today’s culturally-sensitive academic, social, and political environments, community-engaged research is acknowledged as more effective than traditional research for addressing real-world problems faced by underserved and disenfranchised populations [14,15]. Community engagement entails both fostering partnerships with agencies that serve a target population and seeking input from community stakeholders associated with that population in order to design interventions that are culturally-appropriate, feasible, and sustainable.

There is no standard recipe for successful community engagement in research projects that involve refugee communities. Lack of a single prescribed template might make this approach daunting for beginning researchers, or for those who have only used traditional research approaches. Therefore, it is imperative that researchers who have undertaken community-engaged research with underserved and isolated communities share their experiences so that the academic community can learn from their experiences. Candid discussion of challenges is especially important for creating a legacy of problem-solving strategies [35].

The lead researchers involved in PRIDE became involved in community engagement activities well before the actual project was conceived and funded. Once funding was obtained, community partnerships were formalized, and partners’ roles were defined based on the extent of their involvement and contributions. Strategies for facilitating community partner engagement were systematized and sustained during project development. This approach has proved successful in developing community-informed products related to PRIDE’s first three objectives. We have learned many lessons along the way. Perhaps most important was that developing and sustaining community-academic partnerships with refugee communities and service providers is not a linear process; rather, it is an iterative process of trial and error that involves multiple starts and stops, ups and downs. Our experience resonates with Wright et al.’s description of community-engaged research as a non-linear process, where researchers need to be prepared to revert back to the beginning, pause to reflect, and start again [36]. PRIDE was funded after two failed attempts to secure a grant. Lead researchers treated these setbacks as opportunities to regroup with core community partners, reflect on deficiencies in the proposed project, and invite new partners who could strengthen the project mission.

Our experience with PRIDE is also a lesson for future researchers to reach out to potential partners early in the life of a project and to invest in collaborative planning with communities rather than seeking token feedback on plans developed exclusively by researchers. Another effective strategy we used was ensuring that our meetings were well-planned with structured brainstorming activities. Planning ahead allowed us to use community partners’ time judiciously, yet productively, while also creating a space for in-depth dialogue and debate. While these operational details might seem trivial, research shows that they are critical for smooth functioning of community-academic partnerships [26].

There were also times when community partners expressed strong reservations about proposed plans. These occasions called for careful conflict resolution and the strategizing of alternative solutions to maintain the necessary balance between research requirements and community partners’ preferences. Although no formal conflict resolution plan has yet been created for PRIDE, the literature recommends that community stakeholders and academic partners jointly develop such guidelines in written format, ideally at the beginning of the project [35]. Existing conflict-resolution templates and models may be adapted for community-academic partnerships [35] such as ours.

Our experience with encountering and addressing tensions between community and academic partners is not unique. Benoit et al. describe similar tensions when working on a community-engaged project with sex workers, also a hidden and marginalized population [28]. Our experience and that of other researchers serves as a reminder that tension in community-academic partnerships is healthy and keeps all stakeholders involved in the project conscious and responsive to divergent perspectives within the partnership [28].

PRIDE’s research team encountered additional challenges in reconciling community-partners’ perspectives with regulatory requirements that the institutional review board at the sponsoring academic institution enforced to ensure the protection of our project participants. Other researchers have shared accounts of similar discord between community stakeholders’ preferences and the procedural obligations of university-based institutional review boards [37]. Previous research also suggests that delays associated with procuring regulatory permissions can threaten community-academic partnerships and derail proposed projects [24]. These concerns have triggered a research ethics discourse on balancing regulatory requirements with the contingencies and exigencies of complex community problems. Within PRIDE, we resolved these tensions through strategic planning and open dialogue with both community partners and the academic institution’s review board. It is important to resolve such emerging tensions with a collaborative rather than adversarial approach. Each new project can serve as an opportunity for community-engaged researchers to educate institutional review boards about the needs and concerns of community partners [38].

Finally, we learned to value the process of community-engaged research as much as its outcomes. Unlike academic researchers, whose training and perspectives encourage them to see evidence-based products as measures of success, community partners tend to measure the success of community-academic partnerships through process-related indicators, such as relationships, communication, and trust among partners [36].

As we reflect on PRIDE’s developmental phase, it is encouraging to note that we were successful in facilitating each of these indicators. Launching the project with a large advisory board meeting was beneficial in terms of cultivating trusting, long-term relationships among the community partners standing together under PRIDE’s umbrella. Making the effort to maintain contact and share updates with community partners, in person and by phone, ensured that lines of communication with the research team stayed open. Dividing the initial advisory board into two task forces and holding subsequent meetings invited continuing input from community partners and also deepened the trust between community partners and the research team [36].

While our community-engagement efforts were largely successful, and while we gained important insights, it is important to note that the account presented here is a reflective commentary from the perspectives of the researchers involved in PRIDE. The absence of community partner perspectives is a limitation of this paper. However, we are in the process of gathering feedback from community partners and also from refugees with disabilities participating in PRIDE. In the words of community development researcher Peter Westoby [39], academics needs to reimagine their work with communities as “a dialogical journey” of discovery. We hope that this account of PRIDE’s journey will offer a roadmap for future researchers interested in community-engaged research with refugee-seeking communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.P.M. and R.H.; funding acquisition: M.P.M. and R.H.; methodology: M.P.M. and R.H.; project administration: M.P.M., R.H., and K.B.D.; validation, K.B.D.; visualization: M.P.M.; writing—original draft: M.P.M.; writing—review and editing: M.P.M., R.H., and K.B.D.

Funding

This project was funded by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (US) (grant number 90IF0110-01-00).

Acknowledgments

The authors express their thanks to Jian Kim, Ivan Li, and Janet Ro of Asian Human Services, Francisco Alvarado of the Illinois Division of Rehabilitation Services, and the research assistants who contributed to this project: Vineeta Ram, Aman Khan, Ayush Misra, Naba Khan, Sumithra Murthy, Kelly Cloninger, Carlene Yearwood, and Elizabeth Harrison.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2016. Available online: http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/statistics/unhcrstats/5943e8a34/global-trends-forced-displacement-2016.html (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- European Parliament. EU Migrant Crisis: Facts and Figures. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20170629STO78630/eu-migrant-crisis-facts-and-figures (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Zong, J.; Batalova, J. Refugees and Asylees in the United States. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/refugees-and-asylees-united-states (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Connor, P.; Krogstad, J.M. Key Facts about the World’s Refugees. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/10/05/key-facts-about-the-worlds-refugees/ (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Women’s Refugee Commission. Fact Sheet: Refugee Program. Available online: https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/disabilities (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Krogstad, J.M.; Radford, J. Key Facts about Refugees to the U.S. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/01/30/key-facts-about-refugees-to-the-u-s/ (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Brown, A.; Scribner, T. Unfulfilled promises, future possibilities: The refugee resettlement system in the United States. J. Migr. Hum. Secur. 2014, 2, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermette, L. Illinois Refugees Medical Cases Survey: Oct 2009–Sept 2010; Unpublished Report; Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M. Occupational upheaval during resettlement and migration: Findings of global ethnography with refugees with disabilities. OTJR 2012, 32, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The Integration of Resettled Refugees: Essentials for Establishing a Resettlement Programme and Fundamentals for Sustainable Resettlement Programmes. Available online: http://www.unhcr.org/52a6d85b6.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Capps, R.; Newland, K.; Fratzke, S.; Groves, S.; Fix, M.; McHugh, M.; Auclair, J. The Integration Outcomes of US Refugees; Migration Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M.; Heinemann, A.W. Service needs and service gaps among refugees with disabilities resettled in the United States. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirza, M.; Matthews, B.; Luna, R.; Hasnain, R.; Alngede, A.; Hebert, E.; Mishra, U.D.; Neibauer, A.; Pyaohn, E. Policy Brief: Barriers to Accessing Health and Disability Services among Refugees with Disabilities and Chronic Health Conditions Resettled in the Chicago Metropolitan Area; Northwestern University and Access Living: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cargo, M.; Mercer, S.L. The value and challenges of participatory research: Strengthening its practice. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minkler, M.; Wallerstein, N. Community Based Participatory Research for Health; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schensul, J.J. Engaged universities, community based research organizations and third sector science in a global system. Hum. Organ. 2010, 69, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahota, A.; Meza, R.D.; Brikho, B.; Naaf, M.; Estabillo, J.A.; Gomez, E.D.; Vejnoska, S.F.; Dufek, S.; Stahmer, A.C.; Aarons, G.A. Community-academic partnerships: A systematic review of the state of the literature and recommendations for future research. Milbank Q. 2016, 94, 163–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldrich, R.; Marterella, A. Community-engaged research: A path for occupational science in the changing university landscape. J. Occup. Sci. 2014, 21, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, J.; Oscós-Sánchez, M.A. Community-academic research partnerships with vulnerable populations. Annu. Rev. Nurs. Res. 2007, 25, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miner, S.; Liebel, D.V.; Wilde, M.H.; Carroll, J.; Omar, S. Using a clinical outreach project to foster a community-engaged research partnership with Somali families. Prog. Commun. Health Partnersh. 2017, 11, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieland, M.L.; Weis, J.A.; Palmer, T.; Goodson, M.; Loth, S.; Omer, F.; Abbenyi, A.; Krucker, K.; Edens, K.; Sia, I.G. Physical activity and nutrition among immigrant and refugee women: A community-based participatory research approach. Women’s Health Issues 2012, 22, e225–e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, M.; Bimali, M.; Cott, A.; Brimacombe, M.; Ruhland-Petty, T.; Daley, C. Methodological Challenges in Conducting Research with Refugee Women. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 38, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brookman-Frazee, L.; Stahmer, A.C.; Lewis, K.; Feder, J.D.; Reed, S. Building a research-community collaborative to improve community care for infants and toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorders. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 40, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.M.; Maurana, C.; Nelson, D.; Meister, T.; Young, S.N.; Lucey, P. Opening the black box: Conceptualizing community engagement from 109 community–academic partnership programs. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2016, 10, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, M.; Maurana, C. Building effective community-academic partnerships to improve health. Acad. Med. 2001, 76, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, E.; Drahota, A.; Stahmer, A.C. Choosing strategies that work from the start: A mixed methods study to understand effective development of community–academic partnerships. Action Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, W.B.; Reyes, A.G.; Rowe, Z.; Weinert, J.; Israel, B.A. Community partner perspectives on benefits, challenges, facilitating factors, and lessons learned from community-based participatory research partnerships in Detroit. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2015, 9, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, C.; Jansson, M.; Millar, A.; Phillips, R. Community-academic research on hard-to-reach populations: Benefits and challenges. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobransky-Fasiska, D.; Brown, C.; Pincus, H.A.; Nowalk, M.P.; Wieland, M.; Parker, L.S.; Cruz, M.; McMurray, M.L.; Mulsant, B.; Reynolds, C.F., III; et al. Developing a community-academic partnership to improve recognition and treatment of depression in underserved African American and white elders. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 17, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, L.F.; Loup, A.; Nelson, R.M.; Botkin, J.R.; Kost, R.; Smith, J.R.; Gehlert, S. The challenges of collaboration for academic and community partners in a research partnership: Points to consider. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2010, 5, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Our Partners. PRIDE: Partners of Refugees in Illinois Disability Employment; University of Illinois System: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016; Available online: http://pride.ahslabs.uic.edu/ (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- The White House, Executive Office of the President. Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States. Fed. Regist. 2017, 82, 8977–8982. [Google Scholar]

- Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). Available online: https://projectredcap.org/ (accessed on 5 February 2018).

- Jones, L.; Wells, K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA 2007, 297, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, K.N.; Williams, P.; Wright, S.; Lieber, E.; Carrasco, S.R.; Gedjeyan, H. Ties that bind: Creating and sustaining community-academic partnerships. Gatew. Int. J. Community Res. Engagem. 2011, 4, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, R.E.; Yerger, V.B.; McGruder, C.; Froelicher, E. ‘It’s like Tuskegee in reverse’: A case study of ethical tensions in institutional review board review of community-based participatory research. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 1914–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, L. The research ethics committee is not the enemy: Oversight of community-based participatory research. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2010, 5, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westoby, P. Developing a community-development approach through engaging resettling Southern Sudanese refugees within Australia. Community Dev. J. 2008, 43, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).