Abstract

Based on two-year ethnography of boxe popolare—a style of boxing codified by Italian leftist grassroots groups—and participant observation of a palestra popolare in an Italian city, the article purports to (a) deepen understanding of the nexus between physical cultures and politics and (b) contribute to understanding the renewal of political cultures by overcoming the disembodied perspectives on ideology. The first section of the paper tracks down the relation that ties boxing to the sociocultural matrix of the leftist grassroots groups. Boxing draws its significance from the antagonistic culture of the informal political youth organisations in which the practice is embedded and reflects the main changes that have been occurring in the collective action repertoires of the street-level political forces over the past few decades. The second section analyses the daily activities of boxe popolare. The paper thereby demonstrates how training regimes manipulate the bodies to inculcate a set of corporeal postures and sensibilities inherent to a mythology of otherness peculiar to the far-left ethos. In conclusion, the lived experience of boxe popolare addresses the importance of placing the situated practices and the socialised body at the centre of the study of political cultures in the contemporary post-ideological era.

1. Introduction

So far, social science has explored the physical culture and politics nexus from different standpoints. According to the grand theories, the theory of nationalisation of the masses retraces the contribution of gymnastics in shaping the modern nationalisms in several European countries [1]. Figurational sportization theory understands the modern forms of leisure and sport in terms of a civilising process, which has tended, over the last three centuries, to diminish the degree of spontaneous violence in order to create productive citizens [2].

In clarifying the political nature of sport, exercise and physical culture, Hoberman [3] highlighted the “ideological differentiation” in sport by taking into account how the most prominent thinkers of both socialist and nationalist cultures conceived bodily disciplines in the Twentieth Century. More recently, reflecting on the somatic articulation of politics, McDonald [4] has analysed the organisation of sport, exercise and physical culture under the fascist regimes in Europe. Sport reforms and physical education curricula were parts of a large-scale biopolitical project aiming at giving shape to fascist personalities and mentalities. As Mangan [5] (p. 1) puts it with reference to global fascisms, “the reasons are not hard to find. Sport develops muscle and muscle is equated with power—literally and metaphorically”.

Shifting their attention from the political forces and ideologies of the past to current everyday life, several scholars have put an emphasis on the role of martial arts and combat sports in spreading beliefs of broader political communities embedded in different social contexts. By studying the wresters’ lifestyle in North India, Alter [6] is one of the first authors concerned with understanding ethnographically how martial settings, working the human bodies, can bring about complex “systems of meanings” [7]; for instance, health and moral reforms. Inspired by Alter, Cohen [8] pinpoints the creation of an “utopian Israeliness” in ju jutsu schools located in Israeli cities, where the youth is exposed to the glorified destiny of the nation through daily training rituals. Analysing the “moral economy of làmb”—a vernacular wrestling in Senegal—Fanoli [9] sheds lights on the Muslim political forces and traditions that contribute to produce the bodies of the fighters.

With regard to popular culture, mixed martial arts competitions across the globe are becoming theatres in which the athletes display political belonging through their skills, discourses and aesthetics. In this sense, the Finnish Nazi Niko Puhakka and the American-Russian anarcho-communist Jeff Monson represent two examples of opposite extremes among dozens of other fighters.

In a similar vein, this paper explores the processes of political cultures’ regeneration through “martial arts and combat sports” (MACS) [10], which can be treated as forms of “physical culture”, namely “cultural practices […] within which the moving physical body is central”, according to Hargreaves and Vertinsky’s definition [11] (p. 1).

The article draws upon data gathered in an ethnographic study about the social organisation of ‘boxe popolare’. The term boxe popolare (people’s boxing) refers to a style of boxing promoted by leftist grassroots groups in contemporary Italy. Boxing is one example of ‘sport popolare’: a set of physical disciplines, widespread in the main cities of the country, carried out in specific spaces and according to alternative forms of organisation compared to mainstream sport and leisure institutions. To be more precise, boxe popolare is arranged outside the jurisdiction of the ‘Italian Boxing Federation’ (Federazione Puglistica Italiana, FPI). Several public fight nights between boxe popolare teams take place throughout the year. These events are illegal and function with reference to a framework, codified by the teams belonging to a network called ‘CAPPA’ (Coordinamento Antifascista delle Palestre Popolari Autogestite), in which trophies or belts are not at stake. Therefore, how does boxe popolare articulate its attitudes and values that define its far-left identity?

The aim of the paper is two-fold. Firstly, it presents fresh data about a hidden physical cultural cosmos—boxe popolare—and, above everything, about the internal makeup of a political (sub)culture: i.e., the radical left in Italy. To date, many studies about leftist grassroots groups focus their attention on the role of these collective actors in the political process at the local [12,13], national and international level [14]. Further studies have considered the leftist grassroots group nodes of the “centri sociali autogestiti (social centres) social movement” [15]. A few studies examine how the practices of the leftist groups interact with mainstream society, producing cultural change; for instance, in music festivals and soccer [16,17].

Only singular and notable exceptions understand leftist grassroots groups in terms of a political culture in its own right, even if it would be more precise to say that “urban antagonism” represents a political subculture since the grassroots groups have different logics of functioning compared to institutional politics [18,19]. The paucity of such explorations seem surprising given that urban antagonism has been part of the European political landscape since the end the 1960s [20].

Secondly, the paper aims to approach the axiological orientation of political groups from an embodiment perspective “centred on the living, moving and feeling social experiences of human beings” [10] (p. 774). In the wake of the “somatic turn” that has stimulated social and cultural theory in the past decades [21], this approach considers the body as not just “a socially construct-ed product, but also a socially construc-ting vector of knowledge, practice, and power” [22] (p. 9). The study of the social organisation of boxe popolare thus tries to overcome the disembodied approach to discourse and ideology by placing the socialised human organism, the situated practices, micropower dynamics and emotions at the centre of analysis. From a theoretical standpoint, the perspective of embodiment applied in the present paper aligns with the processes occurring in the current “post-ideological” Europe [23] (p. 727), where political identities are not declining entirely due to the collapse of the modern society, the “grand narratives” [24] and the mass organisations. Rather, these are increasingly guided “by the manner in which people participate and interact through the social networks which they themselves have had a significant part in constructing” [23] (p. 718).

In order to better illustrate the perspective and ground the study about the social organisation of boxe popolare within the ethnographic method, I begin with a discussion of the emerging explorations of embodiment in martial arts and combat sport through ethnography. In the third section, I elucidate the methodology used for the research. The fourth section is devoted to the space of boxing practice by focusing on boxe popolare in an Italian large urban area. The fifth section is devoted to the time of boxing practice. It reconstructs the path of the boxer enculturation according to the pedagogy of one ‘palestra popolare’. Both Section 4 and Section 5 begin with an overview of the main concepts and hypothesises that guide the interpretations that follow. The conclusion summarises the main findings and highlights points of debate for future inquiries.

2. Embodiment in the Ethnographies of Martial Arts and Combat Sports

The term “martial arts and combat sports” (MACS) refers to a huge range of physical culture practices [10]. According to the “triadic model” proposed by Channon and Jennings [10] (p. 777), the spectrum of these physical activities includes “combat sport disciplines”—such as boxing and MMA—“military/civilian self-defence systems”—for example, Krav Maga—“traditional and non-competitive martial arts”—as Silat and Taijiquan—and practices “struggling these boundaries”.

The ability of creating and recreating martial arts and fighting/self-defence systems represents one of the more astonishing traits of human cultures. Over the last two decades, the ethnographic approach has been providing a crucial contribution for sociological and anthropological understanding of the embodied practices of MACS throughout the globe, as well as for the development of the emerging interdisciplinary field of “martial arts studies” [25].

Although the increasing ethnographic inquiries are heterogeneous, it is possible to claim that they share a unifying concerning in “embodiment”, that is a “paramount interest in the embodied experiences, sensations and life worlds of MACS practitioners” and supports [10] (p. 775).

To date, embodiment explorations in MACS have been conducted with a variety of approaches, as more traditional “thick participation” and description [26], “sensory ethnography” [27], “ethnobiography” perspective [28] and “netnography” of MACS cybercommunities [29]. In addition, several studies have conducted “narrative analysis” on practitioners’ viewpoint about their own experience and on official documents; for two example, see [30,31]. Despite that the conducted narrative analyses are not based on fieldwork and participant observation, these studies have contributed to shed light on and deconstruct important features of MACS physical culture

From the theoretical perspective, scholars have applied a variety of theorisations and concepts. However, the well-established Eliasian “civilisation” theory and Bourdieusian notion of “habitus” constitute the two main frameworks in current ethnographies [32,33,34].

This growing body of literature is deeply influenced by the trailblazing studies of Wacquant on the plebeian bodily craft of prize fighting and of Downey on capoeira [35,36]. Both authors examined the experience of two martial arts using their body as the instrument of data collection. In particular, the book entitled Fighting Scholars presents of a variety of explorations in embodiment within a broad range of MACS that are theoretically and methodologically driven by previous studies of Downey and, especially, Wacquant [37]. The examinations of specific practices address a series of topics and offers a paramount contribution in outlining the current research agenda.

2.1. An Ever-Expanding Research Agenda

Regarding the state-of-the-art literature, even if the anthropological and sociological inquiries are ongoing, some clear lines of research underlie the existing ethnographies of the MACS.

First and foremost, one of the main substantive topics of empirical research deals with the technical skill of the art. Several inquiries deepen the processes of “techniques of the body” transmission and acquisition [38]. On the one hand, many scholars describe in detail the phenomenology of the embodied micro-processes occurring within the training groups that give shape to the interconnected set of dispositions—i.e., habitus—associated with MACS [31,39]. On the other hand, scholars put more emphasis on tacit knowledge of technical enculturation and habitus acquisition by showing, as Delamont and Stephens do in their study about diasporic capoeira in the U.K. [40,41,42], the symbolic significance attached to bodily postures; such a thing called by Bourdieu the “meaning of the game” [33]. Acquiring a habitus means embodying a state of body and a state of mind [34]. The way in which capoeira practitioners’ shape their habitus relies on the group to which the students belong and both on the individual biology and individual biography within a specific culture.

Strictly related to the study about social construction of specific martial artist identity, the ethnographies address a series of issues related to the topic ethnicity, namely collective identity, belonging and authenticity. For example, the compelling book of Delamont, Stephens and Campos on capoeira [43]—which summarises a decade of inquiries—shows how a diasporic martial art allows practitioners to embody the “exotic other”. In so doing, they change embodied traits that define the native/national culture shared by the practitioners. In a different vein, Nardini studies the modern Gouren—the wrestling style practiced in Bretagne—to demonstrate how the practice develops attachment of youth to Breton ethnic identity in the current multicultural and globalised France [44]. The study of Beauchez about boxing in marginalised French neighbourhoods argues that the discipline constitutes a social resistance practice for the citizens with an Arab background and a means to affirm a collective identity that subverts the dominant representations that reproduce the social marginalisation of certain groups [28]. With regard to authenticity, Spencer deconstructs the “Westernisation theory” of Eastern culture by highlighting the commitment of Western Thai boxers—that is, an integral part of the practitioners’ habitus—to travelling in regions of Thailand to experience the authentic Thai fighting style [45].

Moreover, the ethnographies of MACS offer several intriguing considerations about gender relations and construction. In the public opinion and mainstream representations, MACS are often seen as sites for reproduction of hegemonic masculinity. For example, the work of Spencer demonstrates that, on the one hand, MMA celebrates the values of the alpha-male identity [31]. On the other hand, as in many MACS male subcultures, MMA fraternities are characterized by openness, tactility and intimacy, without the fear of homo-sexualization accompanying such a thing [10]. Channon’s inquiries provide several counterintuitive examples that face the “hegemonic masculinity”, “gender order” and sexual discrimination theses [29,46,47,48]. On the contrary, MACS can represent the locus for experimenting with sex integration and sexual orientation acceptance—by the communities of the practitioners and the fans—that are not common in other popular sports and physical cultures. In terms of female experience [49,50], the findings of several case-studies across the globe highlight the potential offered by self-defence practices, vernacular arts and combat sports to empower women and liberate them from the patriarchy relations. However, such outcomes are never fully guaranteed and vary across countries and practices.

In relation to issues of gender dynamics and sexuality, ethnographies focus attention on the management of violence, which is intrinsic to every fighting practice. Drawing from the civilising process theory of Elias and Wacquant’s argument of the gym as “civilizing machine” [51] (p. 449), which protects the club members from everyday violence teaching them how to internalise self-control between and outside the ropes, some participant-based studies about boxing, aikido and MMA, for instance, pay attention to the ability of taking and giving pain following certain implicit norms of conduct within the gyms or the dojos. Findings suggest that managing violence and “confrontational tension” are crucial factors for becoming attached to the community of the practitioners and acquiring specific fighter habitus [27,37,52,53]. With similar theoretical references, but different substantive interests in civilizing processes within a nation, by studying the vernacular practice of “stick fighting” in Venezuela, Ryan touches a relevant point of debate connecting the production of a “warrior habitus” to the social reintegration of populations that were exposed to violence in their past social experiences [54].

Self-transformation by means of MACS is another broad topic that has been approached in relation to miscellaneous issues. For examples, ethnographies of Wing Chun in the U.K. [55] and Kalarippayattu in south-west India [56] demonstrate how commitment to a martial art can assume religious meaning. The authors suggest that, for the core members of different organisations, the experience of self-transformation through martial art can evolve from an “efficacy” perspective to a “sacralised” activity over the life course1. Other emerging explorations about the MACS, self and society nexus are expanding their interest towards a variety of issues as the pursuit of “health” and “wellbeing” through the practice [60] or the development of an “environmental awareness” [61].

Within this agenda, the somatic articulation of politics remains underexplored excepting the afore-mentioned inquiries of Alter, Cohen and Fanoli about different cultures of nationalism [6,8,9]; and none of the quoted ethnographies refer to Western countries.

This does not mean that scholars are not interested in politics broadly speaking. Techniques of the body and enculturation are a means to reproduce, renew or conflict with traditions, beliefs and values [38]. Cultural identity is a political claim for the social groups in the public realm [62]. Gender order is a matter of politics [63]. The relationship with violence differs across social classes, sexes and political ideologies [64]. Civilising processes are related to political change at the institutional level [32]. In theoretical terms, politics can be framed as everything that reshapes the existence and transforms the self as religion does [65].

Nonetheless, from a substantive level, current ethnographies do not connect empirically the popular practices of MACS to the political cultures and identities circulating in different societies. This article engages with the existing literature to address the underestimated question about if/how habitus associated with specific physical disciplines vehicles axiological orientations of political cultures embedded in a different milieu. My general argument sustains that MACS may be seen and approached in terms of a medium for the embodied transmission, both explicit and tacit, of politics. Being promoted by leftist groups, boxe popolare offers a magnifying ethnographic entry point for grasping the mundane ways by which political culture socialises, rather than focusing theoretical and analytical attention on the role of the extant representations undergirded by political forces in shaping mentalities and social conducts.

3. The Carnal Ethnography of Boxe Popolare2

Like several recent ethnographies of martial arts and combat sports, the study methodology of boxe popolare is significantly inspired by Wacquant’s inquiry on boxing in the U.S. post-industrial black ghetto and applies the premise of “carnal ethnography” [35,66]: a brand of research based on deploying the researcher’s body in action in the field. Recently, Wacquant has clarified the epistemological presumptions of this proposal in terms of “immersive fieldwork through which the investigator acts out (elements of) the phenomenon in order to peel away the layers of its invisible properties and to test its operative mechanisms” [22] (p. 5).

For this purpose, apprenticeship represents a powerful method in understanding the “social nature of epistemic, affective, and moral dimension of embodied practice” as “fighting scholars” put it [37] (p.1). More precisely, the practical acquisition of the corporeal and mental dispositions of the social agents serves as a vehicle for penetrating their logics of assemblage and meaning. Quoting Wacquant and his double usages of “habitus as a topic and a tool” [67], “the apprenticeship of the sociologist is a methodological mirror of the apprenticeship undergone by the empirical subjects of the study” (p. 5). Furthermore, for Downey, Dalidowicz and Mason [68] (p. 183), the accomplishment of social competency may offer “an essential research method” to study bodily arts and martial arts. More precisely, apprenticeship-based research provides fruitful opportunities to track down the pathway of social inclusion, access emic knowledge, delve into the pedagogical dynamics that regulate power relationships and technical proficiency in a situated context.

Without any previous experience in martial arts, I practiced boxe popolare over the last two years. In April 2016, I decided to join a boxing team conducting a covered “observant participation” [35]. Since then, I trained three/four times weekly, practicing sparring with the men and the women of the gym and became, day-by-day, an established member of the team. This involvement has allowed me to experience the social genesis of the local “pugilist habitus”; “that is, the specific set of bodily and mental schemata that define the competent boxer” [66] (p. 224). At the end of every training session, I took notes of such a process in a fieldwork diary by writing the events of the day, the recurring training boxing routines and the locker-room chat before and after the classes. Therefore, the personal acquisition of the pugilist habitus allowed me to gather data about the pedagogical mechanisms of its production and conjoin the boxing gestures and routines to their attached connotations. Boxe popolare apprenticeship also allowed me to create a relationship of trust and friendship with the core members of the gyms and disclose to them my research interests after a few months of fieldwork. Thanks to my direct involvement, I obtained the permission to record training to better understand some implicit rules underlying the daily interactions.

In this way, borrowing Wacquant’s usage of a Garfinkel’s expression [66], I “followed the animal in the foliage” [69]. Along with the boxing team, I sparred in other gyms. I got the access to the backstage of the fight nights playing the role of the video maker, the motivator, the ticket clerk and the supporter. In June 2016, I attended the gathering between several boxe popolare teams in which the gyms of the CAPPA network created the fight night regulatory framework. In that event, the gyms defined the equipment of the fighter, the role of the referee, the judgment criteria and some rough fair play ideas in order to figure out a shared definition of boxing; or, to put it differently, the “meaning of the game” [33].

The trust I established over time within the boxing community has given me the chance to conduct forty-six semi-structured interviews across the gyms of the same urban area. Ten gym founders were interviewed with regard to the palestra popolare project. Sixteen boxing coaches and fifteen practitioners—chosen on the basis of age, sex, ethnicity, sport and political background—were interviewed about their social trajectory and their commitment. Two former boxers who had decided to leave the gym before I trained were interviewed in relation to their dropout. I have also collected information in interviewing three political activists of the 1970s who practiced martial arts in the leftist political contexts.

Last but not least, I collected documents from websites—for example, radio interviews, blog pages, information on the Facebook pages—and stored the material culture and the existing first-hand literature about boxe popolare, e.g., books, fanzines and leaflets.

Much data were gathered, and just some of them are presented in the pages that follow. I choose to use pseudonymous for identifying practitioners and organisations in order to ensure confidentiality and anonymity. Due to a visiting period abroad during the PhD programme, I could not complete my apprenticeship and step into the ring to represent the gym where I trained for many months. ‘This gym is your home’ the oldest coach of the gym said when I recently apologized for my three-month absence because of a new job and an injury. To sustain the importance of fighting in the boxe popolare community team after a long period of training, he added:

‘Don’t exaggerate in training regularly because we should push you in competing. That’s what you can do in order to return us your research finding’.—Patrick

3.1. The Main Research Location: Bread and Roses Club

The main research location of the study is a typical palestra popolare gym that I call ‘Bread and Roses’ from here onwards. In order to “methodically historicise the concrete agent embedded in concrete situations” [70] (p. 171), the Bread and Roses environment has provided relevant insight into exploring the articulation of a political identity by means of MACS for the following reasons.

First, the gym is located in a meaningful political area of the country. The gym is in one of the oldest neighbourhoods of a downtown in one large city. Since the beginning of the Twentieth Century, the neighbourhood developed around a network of water channels in a sort of gangland inhabited by heterogeneous social classes and ethnic backgrounds; in local popular culture, it was defined ‘The Kasbah’. Over the years, the location nearby the city centre, the tradition of tolerance and the low rental for the apartments attracted several militants from all over Italy. From 1972 to 1979, more than forty leftist groups—such as parties, social centres and radio stations—stationed their headquarters in this neighbourhood. The mapping does not include the countless “third places”—bars, pubs, restaurants, barber shops, clubs, parks, open markets—and the private houses that composed the milieu [71]. One militant of that period uses these words to describe the effervescence of the area:

In the Seventies, red and black flags waved in that mythical fortress surrounding the water channels. Several urban legends circulated across the city. Perhaps, one of the first ‘Brigate Rosse’ [the well-known terroristic leftist group] headquarters was located down there […] The workers’ taverns were turned into roaring political and sociability spaces in which the traditional chants about the local underworld merged with the political songs […] This peculiar territory was a recognized Zenith of leftism, engagement, and freedom. At the entrance of [a popular bar …] someone wrote: ‘this zone is to all those who are the others; otherness means beautiful’.[72] (p. 173)

The neighbourhood is massively gentrified nowadays. However, it continues to maintain a crucial significance for the political imaginary, although only a few ‘Indian reservations’ of the radical left—to quote what one of my informants has said once—are still existing. This is the case of the gym, which mirrors the transformation of the local political scene in which the boxing team is imbricated. The gym is located in the courtyard of a building. In the 1970s, it was squatted in a mass mobilization campaign for multiple purposes: housing; union support; leisure and culture. In the origins, the gym space was devoted to carpentry. After a period of under-use, it was arranged as a gym by some anarchist skinheads in the early 2000s.

Second, the choice of this gym as a research location is due to the fact that the Bread and Roses club is one of the first palestra popolare in Italy. At the local level, many of the gym’s founders had practiced martial arts here before they built up a dedicated space in other neighbourhoods. The connections among the founders’ impact the organisational features of the gyms, regardless of their urban location and connections to a social centre. All the palestre popolari in the same urban area are manged by the attendees in squatted or rented spaces. Mirrors, benches, punching bags, ropes, gloves, pads and further boxing equipment are partially recycled, given by other gyms often. The gyms present the same symbolic structure. Political icons, flags, tags and stickers quiddle the walls, the doors and the lockers, creating a patchwork that depicts the orientation of those who train in these spaces. In every gym, sport images and icons are relatively scarce compared to the political ones.

Third, the boxing team of Bread and Roses is one of the central nodes of the CAPPA network at the urban scale and the national scale. The team is part of the fight nights organising committees, both supporting the boxing gatherings and training those who fight. A ring manufactured by an artisan working in a squatted factory is placed in the basement of the gym. The ring is adopted by the boxers belonging to different teams to train for the fight nights in specific sparring sessions. Training with the fighters and observing sparring sessions gave me the chance to investigate some dynamics between the groups and better appreciate the importance of the sparring. To emphasise the relevance of the infrastructure, this ring is being used for the fight nights held in the city. Apprenticeship of boxe popolare in the Bread and Roses club thus has meant learning the embodied practice of boxing and uncovering its moral universe in one of the focal points of this boxing community. At the same time, the boxing team is enmeshed in a web of relationships with other past and present political groups and gyms. Hence, the membership provided the “carnal connections” with other sociocultural leftist groups to test broader interpretations [73].

4. Contextualising Boxing

The first fundamental hypothesis guiding the study is that deep structural and symbolic relationships connect a specific kind of boxing to the orientations of the repertoires of the radical left in Italy. This particular political culture emerged in Italy in the 1960s among the youth at that time thanks to the praxis of creating self-managed organisations that would be independent from the parties.

In this section, I argue that the organisation of boxe popolare embodies the “antagonist attitude” of the far-left milieus reflecting the evolution occurring in the values and the logics of their conflicting collective actions [16]. Boxing marks a general trend: the shifting from power-achieving strategies—characterising the first generation of grassroots organisations—to daily-resisting tactics. Melucci [74] defines these tactics as “challenging codes”, which means the invention of alternative moral spaces inside the city for fighting commodification of culture, on the one hand, and cultural traditions shaping several spheres of everyday life, on the other hand.

To grasp how boxe popolare sustains a leftist identity in contemporary Italy, I historicize the practice in relation to the grassroots leftist organisations embedded in one of the larger metropolitan areas of the country. In the following section, two key dimensions are explored: (a) the organisational style of martial practices over the years; (b) the accounts of the diffusion of boxing according to the founders and the coaches of palestre popolari.

4.1. From Revolution to Challenging Codes

In Italy, the youth political participation outside the parties and masses’ organisation started in 1968, in the period of mobilisations that would have changed the cultural, political and social scenario of the country years later. In 1969, the bomb explosion in ‘piazza Fontana’ in Milan—due to a neo-fascist terroristic attack—marked the beginning of the ‘anni di piombo’ (years of lead): a period embracing the end of the 1960s and the early 1980s that was characterised by massive political engagement—also known as “the movements season”—and violent confrontations between street-level forces throughout the country [75]. By that time, several leftist grassroots groups and new far-left parties composed the political mosaic. Political demonstrations occurred about every day throughout the country. Every march was shielded by the “military apparatus” of the city “movement”.

In accounting his experience, one member of one of these groups—a well-known proletarian street gang converted to political engagement—clarifies the importance of practicing martial arts for street-fighting purposes [76]. The gang led the demonstrations and was in charge of clashing with police, as well as in chasing fascists throughout the city. Along with Marx and other theoretical readings, debates concerning the different leftist positions among the “comrades” and planning strategies to face the enemies in the streets, karate classes were part of the daily activities of the gang. Martial art practice was conceived as an integral part of their “fighting culture”: a vehicle to forge determination and solidarity “in order to fight while staring at the eyes of the boss’ toadies”, namely, the police forces [76] (p. 110).

In 1975, the birth of ‘centri sociali autogestiti’ (self-managed social centres) opened a new stage in the developmental history of youth civic cultures. Social centres were created in squatted buildings to replace the traditional working-class unions and associations disappearing during the first stages of the deindustrialisation process [15]. These multifunctional illegal spaces promoted countless practices aiming at promoting alternative values in answering the needs of the youth and several fractions of the marginal populations. Promoting both “single issue” campaigns and underground culture, the politicised groups started to move the conflict against society from a muscular direct confrontation in the streets to a more indirect “symbolic level” [74,77].

Throughout the 1970s and the 1980s, martial arts were practiced in these spaces by small groups, yet remained anchored to the militant cultural baggage. One former activist describes the microclimate of a martial class along with its scopes:

‘Martial arts among the grassroots groups were born in the Seventies. The first ‘centro sociale’ experiences were projected to forge the avant-gardes that would have changed society, too. You know, self-defensive skills were part of the militant toolkit. Street-fighting was ‘the main activity in sport and leisure’ I said with friends […] I remember I practiced muay thai with a group of girls in the back of the kitchen or other parts of the squatted space. Militant feminism was massively active by that time. We wrote messages against patriarchy on the porno-cinema façade; we distributed leaflets pro-abortion, against drug dealers, and so on and so forth […] I wasn’t a good and disciplined boxer. But muay thai was quite useful to reinforce my mental attitude at least’.—Elena

The former activist sketched a period in which practicing martial arts was organic to militant projects of subverting the axiological orientation of the entire society. Muay thai was practiced in a space not entirely devoted to it. The art was connected to further political activities, and it was not accessible to those who were not included in the militant clique.

In the 1990s, social centres and similar self-managed groups reframed their repertoires, implementing their practice according to functional specialisation and “bottom-up welfare” [13] logics. At the same time, the politicised groups reinforced their conflicting orientation towards specific institutions, instead of the whole social and cultural system.

4.1.1. Against (the Moral Ideals of) FPI Boxing

In the wake of these logics, sport popolare has been mushrooming over the last two decades. Along with soccer and basketball, boxing is one of the main physical disciplines promoted by the leftist groups, and its organisation style reflects the trends sketched out above.

Actually, boxing is now practiced in dedicated spaces, which is palestra popolare, and run by dedicated groups. The classes are advertised on the Internet and are easily accessible. While the average monthly fee in a mainstream boxing gym of the city costs €70, boxing is free in four out of ten palestre popolari. In four gyms, the monthly fee fluctuates between €10 and €20 per month. In two of those, the fee costs between €20 and €40. No membership cards are required/provided to practice in a boxe popolare class. This kind of boxing is illegal because it is carried out outside the boxing jurisdiction; in Italy, everyone that wears a pair of gloves outside an FPI boxing gym could be reported. In addition, none of the normally required health certificates to carry out exercises and sport are requested by any of the teams. Moreover, the coaches train without any license. Their role is based on the personal boxing skill, in general, and experience in boxe popolare, in particular.

The difference between a palestra popolare and a mainstream boxing gym has not only to do with accessibility, prices and (il)legality; it embraces the practice per se. The founder of the first boxe popolare class, as well as the main teacher of the current coaches in the Bread and Roses club expresses this point with the following words:

‘The first boxe popolare class was created to reframe the traditional concept of boxing. Ten years ago, I think boxing in FPI was perceived a right-wing practice […] The boxer had to injure his body in order to become a proper fighter. Fighting was compulsory, unless one would be stigmatised as ‘faggot’. I was wondering: is it really important fighting in public? Is it mandatory knocking out the opponent? I questioned myself many times because I didn’t like what I’d experienced before. Boxe popolare has been flourishing since 2007. I’m happy that so many people share this fundamental idea today’.―Francis

This seems to echo Bourdieu’s stance [78], when he refers to sport and exercises in terms of distinctive practices that spread “moral ideals”. More precisely, such a distinction would affirm political views and values that draw their sustenance by symbolically differing from the ones that are promoted in the concurring practices of the same field [44]. The mechanism that defines boxe popolare as a practice that spreads values of an alternative political community compared to boxing in FPI gyms is strongly highlighted by another coach:

‘Someone has told me, it’s a legend probably that would warrant to be proved, that ‘niggas’ are brutally punched in the Olympia gym [a well-known boxing gym of the city] The ‘negro’ is like a punching bag ... [he uses the strong politically incorrect language deliberately with reference to mainstream gyms to connotate the racism of the FPI boxing tradition according to his view] Brian [a black asylum seeker] is training with us for one year. I boost his self-confidence constantly. I want him here in the gym; I want him to fight. I wish he would be active in his daily life, not just waiting passively a certification from the court… I wish he would create fair friendships […] I mean, we should act differently compared to those fascist gyms!’.—Stefano

Boxing in FPI would boost a set of moral attitudes completely opposite to a leftist identity. As long as the ‘legend’ is still existing and circulating, boxe popolare teams use rumours, as they are the benchmark of alternative values.

However, the production of an alternative moral universe compared to FPI boxing is also related to the collusion of radical right groups in the martial arts field. For example, the ‘Wolf of the ring’ is an informal association of athletes that is active both in mainstream gyms and in organising self-managed sport-related events for promoting moral ideals as ‘militarism’, ‘sacrifice’ and ‘belonging’. The organisation is connected to ‘Lealtà e Azione’: an emerging neo-Nazi party widespread among the youth in the northern neighbourhoods and the outskirts of Milan. The party emulates the activities and the organisational style of ‘Casa Pound’ in Rome. Currently, the most popular neo-fascist party promotes specific associations involved both in FPI boxing and in organising alternative events to the general public.

According to the boxing coach of an anarchist gym, the promotion of a martial art in a grassroots leftist gym also has as the goal of the limitation of the diffusion of the current forms of fascism:

‘I guess that every single guy participating in our class counts one fascist less in current society and fewer enemies I have to face in the street’.—Simone

4.2. The Narrative of an Elective Affinity

The last quotation suggests that the changing of the logics of actions has not entirely eradicated the strategy of, and the interest in, street fighting. Although the grassroots groups occupy slightly different positions in the political spectrum, facing police and opposite street-level groups remains the most fundamental shared repertoire—both real and imagined—that defines the urban antagonism in terms of a political subculture [79]. Indeed, there exists a sort of “elective affinity”, to use a Weberian term, that brings together boxing and clashing in order to sustain an antagonist attitude. A coach addresses the continuity between boxing and direct actions with these words:

‘Boxing training is relevant to carry on the values we trust instead of fighting per se. We’re the streets: that’s why the body is more important than the mind sometimes… public speaking and debating are fine, but they don’t top off politics. We should be as well muscled as possible considering that both cops and fascists are hyper-trained these days’.—Mario

In this quotation, ‘action’ and ‘rhetoric’ are seen as the two poles that compose the overall politics conducted adopting the whole body. As Löwy [80] explains, “elective affinity is a process through which two cultural forms […] who have certain analogies, intimate kinships or meaning affinities, enter in a relationship of reciprocal attraction and influence, mutual selection, active convergence and mutual reinforcement”.

Much like in other martial arts fields, where several practitioners carry out a practice because of their former street fighting background [81] (p. 38), the fighting continuum explains the “self-selecting” accorded by the activist for this martial art [66]. In their interview, all the coaches plus several practitioners that act in current political groups—social centres, unions, neighbourhood associations—have justified their boxing interest for self-defence purposes in risky direct actions and to shield their bodies from the unpredictable neo-fascists assaults.

However, boxing and street fighting affinity play a central role in sustaining a political identity, not just at the individual level. The reason why boxing is so often practiced among the leftist grassroots groups is due less to a crucial factor such as the material accessibility of the practice rather than a vehicle for political identity confirmation and transmissions3.

This field note highlights the perspective of the main boxing coach of Bread and Roses club:

I ask Patrick information about the kung-fu class recently implemented in the gym. The coach shakes his head and reacts strongly: ‘I hate eastern martial arts! The philosophy of martial arts is so fucking concerned with achieving nirvana. That’s Bullshit! Everything is going wrong today. Should I be a tamed citizen? Boxing is our business. Due to training, we’re not doing any revolution, but we learn how to resist at least. Boxing pumps up our immune system and mentality. What will you do once police smash your head in a demonstration? I’m not saying that violence solves social problems. However, a collective passive resistance is a powerful weapon at our disposal. We don’t have to be like those martial masters that fire themselves in silence to blame the system. That’s what’s happening in Asia where martial artists have some political roles, yet not effective here and now […] In my opinion, one aim of boxing in palestra popolare is to prepare people for direct action. It doesn’t matter if clashes never happen. We’ve got to be ready, anyway’.(Field note. 13 March 2017)

By highlighting the hypothetical chances of facing police, Patrick outlines that especially boxing, compared to other martial arts and physical cultures, contributes to defining the boundaries of an “imagined political community” of resistance to which the boxers’ bodies should belong [82], regardless of real direct actions. This contribution is narrated in several ways from the boxing teams thanks to language and symbolism, which are two tools for community building in Andersons’ perspective [82].

For example, in the fight night held in the city in 2016, the organising gyms distributed sheets to advertise their specific martial art. The last sentence of the leaflet was this: ‘when the fascists raise their heads, our fists will knock them down; let’s stand for boxing; let’s resist’. Quite often, the nexus between boxing and direct action is represented by the gym’s symbols, logos and names. The next conversation presents a paradigmatic example of defining the boundaries of a political identity narrating the boxing and clashing affinity:

- Lorenzo:

- ‘Why is the bull the logo of your gym?’

- Luca:

- ‘This is an interesting point. About two years ago, I was in a demonstration with Johnny, the one who helped me in building up the gym. We were ‘doing the situation’: we’re crossing each other arms and kicking the riot police that locked the street pared. Suddenly, one cop exclaimed towards one of his colleagues: ‘help me against these fucking bulls’. Ha ha ha [Luca laughs] The day we’re deciding the symbols of the gym I proposed to insert the bull […] to remember that demonstration of force […] One fella said: ‘well done, dude. Both fascists and hipsters will think twice before stepping in our lane’. —Luca

4.3. A Distinctive Social Word

Although boxing draws its meaning from continuity to the broader political community and presents strong similarities with several grassroots groups in terms of organisational patterns, languages and symbolisms, boxing produces a further difference—that is physical, relational and moral simultaneously—in comparison to the rest of the activist networks. A field note written at the end of a training session while walking in the neighbourhood with Patrick depicts this intrinsic “ambivalence”, borrowing Simmel’s expression [83]:

Patrick comments the quick encounter we had in front of a pub with one of his acquaintances. The guy was crazy because he had found a leaflet attached to a wall signed by a housing organisation. ‘What the fuck… He’s angry because he thinks this is not the territory of that organisation’, Patrick exclaims. And he adds: ‘I know this boy and how his brain works: he’s a dope fiend. It’s such a shame the comrades are wasting their life. Drug using is one of the main causes of our failures […] I’m happy when Ali and Gianluca [two young boxers] tell me: ‘I’m different. I hate cocaine’. This is an important result. How could you trust in one who declares his anticapitalist identity and spends money on drugs? Drug addiction triggers the worst dynamics between humans. You’d fuck everybody for your daily dose. I don’t want to say that we, as comrades, must be straight edged. However, this could be an extreme example of commitment and determination. How could one act differently? I consider the importance of promoting real solutions. The gym is one alternative. Human beings are like dogs, once they get the bone they won’t let it go!’(Field note. 3 July 2016)

According to every “idioculture”—”cultural forms as originating in small-group context”—boxe popolare teams represent small-scale worlds on their own, with their specific networks, routines of interactions, beliefs and norms [84].

The Bread and Roses club provides five boxing classes over the week. Fifty people on average attend the classes. Turnover of the new members is quite high due to the accessibility policy of the gyms. In my experience, each class is attended by about fourteen people, both females and males, with a prevalence of the latter. The practitioners are between 16 years old and 40 years old; but most of the boxers are about 25 years old. The boxers are heterogeneous in terms of ethnic backgrounds, social class, education, sport and political background, as well; that means they could be classified as political militants or disengaged citizens that share the general value orientations of the group. ‘Fascists’ and ‘cops’ are considered the outsiders. Four ‘Stalin’—the name given to the wooden bats used to face political enemies by the leftist groups—lay down the stairs to be used to protect the space from undesired intruders.

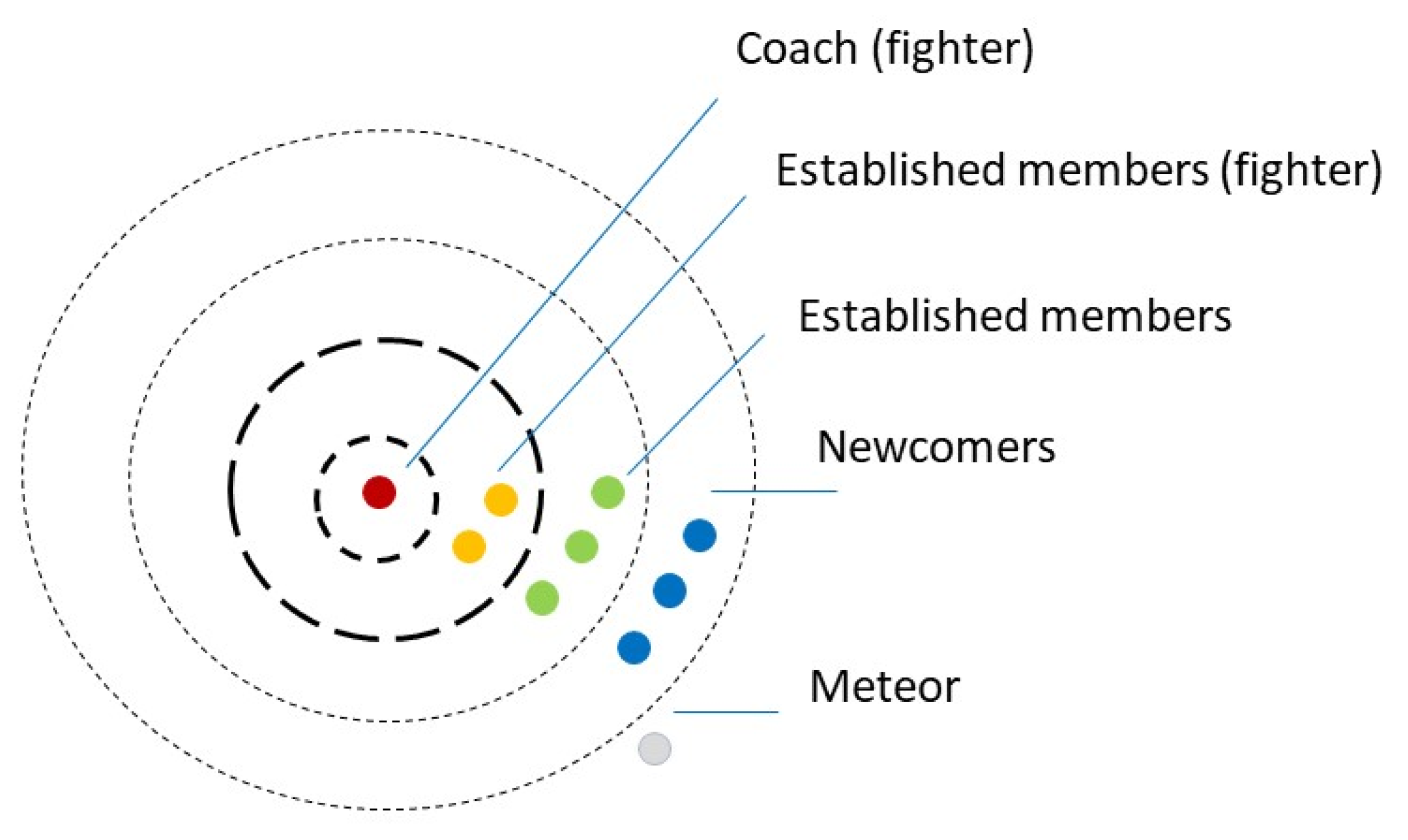

Much like every boxe popolare class, both the gym space and the classes are managed by practitioners. The following figure represents the structure of the teams as an ensemble of concentric circles.

Figure 1 shows the two internal circles that refer to the clique of the ‘fighters’, which means the established members allowed to fight in public. The clique of the fighters corresponds to all those who are involved in coaching. They are recruited within the team and chosen via a process of autonomous regeneration marked by fighting in public representing the gym: a “rite of institution” that endorses the individual transition from one status to another [85]. In other terms, the greater the individual participation and know-how acquisition inside the “communities of practice” [86], the greater the responsibility to run the team. All the coaches consider their commitment—that is completely volunteer based—as a form of ‘activism’.

Figure 1.

The (ideal) team structure of one boxe popolare class.

The other roles are the established, namely the practitioners that do not fight, and the newcomers, namely the ones attending the class for one month. The ‘meteor’—an idiomatic term used in the gym—is a marginal figure that is located at the border of the team. This role is the one of the former boxers who left the gym to box in FPI; but they are still connected to the established core members of the team and train the boxers for fighting in specific periods.

Every training session is led by one coach supported by established fighters. However, the boxing corresponds to a specific style—that means the defensive guard and the attacking movements—shared by the different coaches over the week. Furthermore, two fundamental rules of the classes are supposed to be shared with the gyms belonging to the CAPPA network: the gloves adopted to spar weigh 14 ounces or 12 ounces and are provided with an extra-padding technology to reduce the force of fist impact; knockdowns and knockouts are taboos avoided in the local boxing curricula.

A few elements of team functioning are clarified with the novices in the first training session. Frequently, this happens when coaching is carried out by Patrick, the oldest coach and the most prominent fighter of the gym:

Patrick speaks with a boxer at the conclusion of his first training session. The boy is a 27-year-old former judoka, and he has discovered the gym thanks to a friend who is involved in a grassroots political group.

- Patrick:

- ‘I’ve noticed your defensive guard is vulnerable’

- Andrea:

- ‘I thought it would be fine’ [he shows a shoulder roll technique]

- Patrick:

- ‘It’s too dangerous! If I saw a boxer acting this guard in our network, he would be a fucking idiot. Only a small number of pro boxers are good enough in this defensive technique. In this gym, the team teaches the traditional guard by pushing arms against the core and the jaw. Certainly, there are several boxing methodologies, but we own a specific style. Today, I’m the teacher. Tomorrow, you will find Laura. Tuesday, you will find Fabio. Another day, Paolo or Enrico will teach. Everyone is a different coach, but boxing configuration is the same’

- Andrea:

- ‘Ok. Super easy. I practiced judo in the past; I will learn boxing very fast’

- Patrick:

- [speaking lauder] ‘Don’t be pretentious! You need time to learn the craft and the surrounding philosophy’

- Andrea:

- ‘Philosophy? It’s just punching each other, isn’t it?’

- Patrick:

- [shaking his head] ‘No. The mainstream gyms don’t teach boxing. They’re promoting ‘fitboxe’ ‘lightboxe’ and other commercial bullshit, because people want to get fit and don’t mind about boxing. This is not our view. Above everything, we consider boxing a political means of self-discipline’

- Andrea:

- [doesn’t reply, he just stares at the coach]

- Patrick:

- [pointing his right-hand finger at Andrea] ‘Those fucking beatnik comrades are pissing me off! They must learn how to find out sources of self-determination. If you accomplish the mental strength to learn a discipline, and being self-disciplined, you can do political stuff. This is the way. No pain no gain, right?’

The boy doesn’t say anything. He rolls up the bands as quick as possible and leaves the gym in silence [I will never meet him in training].(Field note. 6 June 2016)

Although it is expressed by words, especially when some norms are violated, internal regulation of the team becomes more visible and clear in conduct; this process seems to be akin to other boxing gyms and martial contexts [66,87].

The observations conducted suggest that those who do not accept to internalise the expected codes of behaviour leave the gym very soon on their own accord. Less frequently, practitioners spend a few weeks in the space. They leave when they realise that the commitment to boxing can affect their daily life deeply.

5. The Political Mythology Incarnate

According to Wacquant [66] (p. 237), “pugilistic knowledge consists of a practical knowledge composed of schemata that are thoroughly immanent to practice”. It follows that discipline training represents a pedagogical process that has a double importance: including the individuals in the practice; absorbing the practice and the knowledge related to it [86]. To say it as Bourdieu [34] (p. 196), “the function of pedagogical work is to substitute to the savage body a body ‘habituated’, that is, temporally structured” and “physically remodelled according to the specific demands of the field” [66] (p. 273). With regard to boxe popolare, pedagogical work has a specific temporality in shaping the local boxer’s “bodily hexis”; that is “a political mythology realized, em-bodied, turned into a permanent disposition, a durable way of standing, speaking, walking, and thereby of feeling and thinking” [33] (pp. 69–70).

In this section, I argue that the daily pedagogy is systematically organised to inculcate the rules and attitudes of boxe popolare in the boxer’s flesh via “direct embodiment” [73]. The following pages show that shaping the local boxer’s bodily hexis lays on a double “ambivalence”, to maintain earlier use of Simmel’s expression [83]. One the one hand, the production of the local boxer’s bodily hexis sustains the attitudes of a broader political community; at the same time, the pedagogical work marks the distinction of the attitudes and the values promoted by the team from the ones embodied by the hexis of different politicised individuals and groups. On the other hand, the local boxer’s bodily hexis reinforces the boxe popolare community and the politics of distinction of the network from FPI boxing; at the same time, pedagogical work marks a further difference among the boxe popolare teams. To sustain the argument, the key dimension explored is the training regimes of the Bread and Roses boxing team.

5.1. A Perpetual Resistance

The pedagogical work in Bread and Roses presents a largely implicit, but strict regulation. Everyone has to respect the same training discipline and follow the same path in order to fight, regardless of age, sex, sport and political background, and other individual factors. One year is the period—estimated by the coaches—to allow a new member to embody the practice kinetically and represent the gym in fight nights for every event occurring over the year; to date, 5/6 fight nights are organised by CAPPA yearly.

Repetition is the main feature of the activities. The yearly calendar envisages the fight night participation as a member of the audience or doing voluntary activities, attending ‘collective training’ with other palestre popolari or in boxe popolare events, assembling with other boxers to manage the gym and cleaning the space.

However, it is especially in the daily training when the boxer’s physicality is being produced. The menu of a class is the same over the weeks and months. One single training session lasts about one hour and 30 minutes. It is carried out collectively and contains the same schedule of activity. First of all, 15 minutes are devoted to jumping rope. Then, 15 minutes are dedicated to warming up gymnastics. After that, a set of floor works—for instance, shadowboxing, weightlifting—are conducted over 15 minutes. Then, 20 minutes are for working the punch bags or the pads. Eventually, the established boxers spend 10 minutes in sparring, while the newcomers along with the ones that do not spar watch the performances. At the end of the class, about 15 minutes are devoted to sit ups and stretching exercises. ‘Work’, ‘working’ and ‘keep going’ are the most common words communicated—or better, shouted—by the clique of the coaches over the single exercise sessions. Every working session lasts three minutes and one minute is for breaks. Timing is managed by an electronic device—a Lonsdale timer—that rules the workouts and the efforts precisely. Such a regulation and the emphasis on ‘working’ sound quite curious by considering that boxe popolare is conceived in terms of a leisure activity. Such a pattern refers to a run-of-the-mill daily training schedule.

For all those who represent the gym in public, workouts intensify, and breaks diminish. Piero’s training session provides a typical example of the fighter training:

Thirty-seven days before the fight night.19.30. I arrive at the gym. Boys and girls bring their ropes and place themselves on the tatami. I greet everybody and start to get changed. Piero does not notice me, he is immersed in boxing with his figure in front of the mirrors. Fabio leads the session. We jump the ropes for three minutes, by alternating different speeds every ten seconds. After twenty seconds, Fabio says Piero: ‘we speed up ten seconds. You do it fifteen’. Pietro executes the instructions for three minutes. Surrounded by the Che Guevara portrait, the Antifa flag and the Soviet art devoted to Vsevobuch [a system of compulsory military training for male citizens practiced in USSR] Piero slashes the air with his fists during the one-minute break […]Around 20.20, Fabio splits the group in two and gives Piero an elastic strip that is being stretched by the boxer across his ankles. The coach gestures towards me and Stefano: ‘collect bands, gloves, and go downstairs in the ring; set the timer on three-minute work and twenty-second break. Bring head guards and mouthpiece: don’t give Piero a hand job, please; he is training for fighting!’ […]We spar two against one in the ring. I and Stefano attack Piero for five rounds. He defends and counterattacks with his heavy fists. After fifteen minutes, I drag my soaking body out of the ring. My lungs burn. My head is on fire due to the punches I have received. I contract my face and breathe deeply. I’m feeling completely wrecked. A completely relaxed version of Piero jumps quietly; he watches the elastic strip and checks the distance between his legs. Fabio joins us in the basement and tells Piero: ‘remains in the ring for sparring’.Three rounds of sparring. Piero spars against Fabio for two rounds and against Stefano for one round. Stefano concludes the sparring few seconds earlier; his nose is bleeding. Piero doesn’t say anything. He spits his mouthpiece in the right glove and ask Fabio: ‘how did I spar?’. Fabio: ‘you did well. But you must be careful. You forward your head instead of the body. It could be dangerous in fighting, because your opponent can anticipate your attack and hit. Check the posture with the strip’ […]Keeping the elastic strip across the legs, Piero concludes training upstairs by practicing six-minute shadowboxing first, and nine-minute punching the heavy black bag next. When I resurface from the basement Piero is striking the punching bag with multiple fists combinations emanating wild sounds. Fabio congratulates the boxer inviting him to conclude the session: ‘very good boy! Ok, it’s enough today. You have worked really well’. While hitting the bag furiously, Piero replies: ‘One minute more… uha uha uha [wild noises] I am aligned to the timer… uha uha uha’ […]I ask Piero while he dries his sweaty body at the end of his exercising: ‘How many days do you train weekly?’. He sighs and says sorrowfully: ‘Only four, dude… only four… I’d train more if I could. But my job and my girlfriend need time’ […]Once he leaves the gym I point out Piero’s commitment in front of Fabio and Stefano—the latter is still fixing his bleeding nose. Fabio murmurs: ‘he is a tough guy!’.(Field note. 7 October 2017)

Because boxing correctly represents an “ongoing practical achievement” [88], consistent training is crucial to physically incarnate the rules and the meaning of the practice. This process seems to be quite common in any boxing field [35,66]. In boxe popolare in this particular team, fighting training lasts two months. In the first month, training is entirely devoted to straighten the boxer’s posture and enlarge the heart muscle for improving personal stamina. Especially in the last month, training is organised around the acquisition of specific attacking and defensive tactics. These physical dispositions own specific symbolic essence. A straight back indicates the self-composure of the boxer. A big ‘heart’ indicates the personal commitment and the attachment to the team. Very often, Patrick says that the boxers he trains own ‘a big heart’ to connotate them positively.

In that two-month period, all the fighters I have observed trained themselves no less than four times per week. In addition, many boxers practice running sessions or other activities outside the gym. Some of them approach fighting so seriously that they decide to take some days off and leave the city for intensive preparation. Examples I have heard of include: finding gyms in other cities for sparring; exercising shadowboxing in the cold spring sea of Corsica twice per day; spending one week in a countryside pigsty to focus on exercises and deal with personal ‘bestiality’.

The devotion of time in training is justified by the coaches in terms of a necessary strategy to face the opponents in the fight nights, especially since new gyms have been joining the matches with a different attitude compared to the one of Bread on Roses:

‘Four years ago, it was different. There were random boxers and the environment was more relaxed. Today, it’s completely different. The boxers are well trained and skilled. Many of them want to knockdown. That’s why I want to kick the guys’ ass. They can focus on themselves to learn how to tackle tension and perform our boxing style that is pretty respectful. I mean, we have never knocked anybody down’.—Patrick

To better prepare the boxers for fighting, the coaches do not provide detailed information about the contenders; for example, his/her body shape, length and boxing style. They just assure the fighters about the same weight and experience of the challengers. Very often, the fighters’ focus on their own training—which turn into a sort of over-training I would say—that causes several injuries.

So far, the 11 fighters I have observed fought injured. They fought with cracked ribs, pain in their back, nose, elbows or knees. Sometimes, they approached the match with bruised eyes, although the team prefers to exhibit ‘cleaned faces’, or a ‘lord’s face’ to adopt another term used by Patrick. For this reason, sparring exercises end one week before the match to let the face recover from past punches and prevent further injuries. However, enduring the internal physical sufferance, which is produced by continuing training, is considered an essential part of the game by the coaches.

Ten days before the fight nightPiero feels a strong pain on his back. He tells us that he would quit fighting. The coach hears his words and reacts resolutely: ‘fuck you, Piero. You don’t give up! You have been training for eight months […] This is what my coach has taught me. Once I had an injured knee and I didn’t want to fight. He got super angry when I had told him my feeling. He said: ‘wear those fucking gloves without complaining. Are you rotten? This is the strategy: you stand in the middle of the ring and defend’. Do you understand Piero? We have mobilised other people. So, you have to respect this agreement. It’s just a 9-minute performance’. The words make Piero’s face turn pale.(Field note. 1 November 2017)

In short, the pedagogical work of training produce a specific “legitimate body” for fighting in boxe popolare [78]. The outcome of training is a hyper-civilised boxer, a “symbolic body” that can perform public demonstrations of self-discipline, control, determination, resistance and solidarity with the entire boxing community by being able to take and give pain, deal with emotional tension and show compassion in limiting the use of force [89]. Therefore, fighting in public means struggling for affirming the broader legitimate moral cosmos surrounding boxing. To some extent, it also means resisting alternative conceptions of the practice embodied by the fighters belonging to other boxe popolare teams. The following section aims to show how the sparring routine can be interpreted as the most relevant physical daily exercise for the continuous (re)production of the boxe popolare moral cosmos.

5.2. The Sparring Dispositif

Although several exercises compose training, “the climax and yardstick of training remains the sparring” [66] (p. 241). Similar to other boxing and martial art fields, fighting simulation is a meaningful pedagogical activity [28,66,87]. More exactly, sparring can represent a small-scale-level “dispositif” in Foucauldian terms [90]: that means a network of interacting routines, discourses, explicit and tacit knowledges created and adopted in specific contexts with the purposes of manipulating the human flesh, energies, desires and thoughts, so as to configure certain power/knowledge relations and shape ways of being4.

In the Bread and Roses boxing team, language enshrines the importance of fighting simulation. Unlike the overall workouts, several “indexical expressions” identify the exercise [88]: ‘turning’; ‘punching’; ‘putting the gloves on’; ‘gloves’; ‘trading’; ‘doing one’. Sparring is the most commented on training routine. It is evoked in other exercises: for example, the coaches mention sparring to explain to the newcomers the defensive guard or to teach a specific punching combo; the established mention of sparring to justify shadowboxing practice and how to relax nerves, or why sit ups are practiced to strengthen the core. Legends and reputations of the boxers are created referring to past sparring performances.

Even if the sparring routines embrace a huge variety of confrontations and do not respect specific norms of action—namely, like the kata or patterns of many Eastern martial art styles [57]—it owns some implicit rules. Actually, sparring is an illegal activity, and every session can cause injuries from bleeding of the nose to breaking bones. Only the established ones—in other terms, the ones able to control their instincts and avoid knockouts and knockdowns—thus spar freely. However, the coaches supervise the exercises constantly by watching the boxers next to them, unless one of the senior members of the team is sparring and managing the situation in actu. The male boxers must wear the 14-ounce gloves, while the female boxers put on the 12-ounce ones. A mouthpiece is mandatory. The head guard is not compulsory except for the sessions that are carried out by those who train for fighting.

In addition, the single confrontations have a certain degree of “legitimate violence” [87]. That means that every “fistic conversation” contains a “lower threshold” and an “upper threshold” of physical conflict and danger [62,82]. The range is not precise and permanent. On the contrary, it represents a negotiated accomplishment varying with regard to the bodily shape and experience of the partners, the yearly calendar, the place of the routine—inside vs. outside the ring—and equipment of the partners.

By considering the dimensions of language and implicit regulation, sparring warrants specific attention. Working out the boxers’ organism, the pedagogy of sparring presents a complex “interplay […] of functions” that produce sets of physical, mental and moral dispositions [90] (p. 195). To say it in Elias’ terms [32], the sparring dispositif sparks off interrelated “sociogenetic” and “pyschogenetic” processes. It means that social, cultural and biological factors interweave. They do not exist with degrees of isolation. Patterns of repeated interactions connect individuals to perform the very existence of social organisations (sociogenesis) and impact on personality structure, corporeal and mental (psychogenesis).

Analysing sparring thus is crucial to highlight both the genesis of the team structure and how the rules, the values and the meaning of the practice are spread and reaffirmed while shaping the legitimate boxer’s bodily hexis.

5.2.1. Relational Dispositions

First and foremost, sparring plays morphological functions and serves to create the boundaries within the gym. In this sense, sparring is a “liminal rite marking the carnal inclusion of the individual in the pugilistic community” [28] (p. 120). The initiation to sparring is a process that varies among the practitioners without respecting any specific norm; very often, the first sparring experience of the boxer is practiced against one of the coaches. Not every established member accepts to spar because of the fear to ‘ruin’ his/her own face; that means, get the body cut, hurt or a bruised eye. All those who do not spar after a period of attendance, and refusing the invitation of the coaches, remain at the periphery of the team. Initiation is a never-ending process because an injury is always a risk. Severe injuries or unintentional knockdowns could occur in every session inhibiting the personal involvement in the practice.

However, once one is allowed to spar, the exercise is largely encouraged with a countless number of partners; in the past two years, I have sparred with more than sixty partners both males and females. Invited to explain the rules of the gym functioning in a radio show, one coach claims: ‘no one can refuse to spar with a partner because of his or her low skills’.

This etiquette rule is a powerful means to create attachment. Although sparring within the correct range of violence makes the exercise useful for both the partners, the effective intensity of the fists can never be achieved easily. In other words, some fixed elements are not enough to define the right degree of legitimate violence. Therefore, while punching each other, both coaches and partners communicate to affirm mutually the “line” of the fistic conversation [93]:

Patrick asks Laura to get into the ring and tells me: ‘now, you work with Laura, she’s an expert’.[…] I attack her quite scared due to her reaction. Patrick shouts: ‘hit, hit! Don’t be afraid to attack her. She punches you four times at the most then she stops. You must attack her as soon as she finishes’. She punches me again and with more precision. One of her hooks impacts on my nose: ‘oh sorry’, she says immediately. I move my head up and down to communicate that I’m fine. Laura attacks me repeatedly and I reply with one of the basic combinations I have learnt—left, right, left hook, right hook.Patrick exhorts me: ‘c’mon, hit this girl, more pressure, more punches’. Laura invites me to do the same: ‘punch me. I want to feel your hooks on my body, give me the overcuts’.Convinced by both, I focus on hitting Laura’s body and face. To react, she holsters up her arsenal composed of sequences of fast hooks. I move towards her left side and throw two uppercuts and one hook to barricade her attacks. I try to take punches without stumbling back (that’s pretty complicated, shit!). When one of her uppercut hurts my mouth, I understand it’s time to keep distance with my jabs. Laura doesn’t want to move backward and attack me again. She clings on my right. I step on the left and double a left uppercut and one right hook (noise of our punches is thumping throughout the room, it’s exciting now!) Apparently, Patrick is enjoying the performance; he jumps, yanks the ring ropes and screams: ‘yes, yes, keep going ha ha ha’ [laughing] (That’s a punches maelstrom, I feel myself both nervous and exalted!).‘Time’s up’, Patrick screams.(Already finished?). I stagger onto Laura: ‘super, thanks!’ (wow, heart is beating, adrenaline is rushing, I would spar five minutes more). A smile crosses her sweating shining face, she tells me breathing smoothly: ‘it’s such a fatigue. Woow. Very, very good. Thank you so much!’. We touch our right gloves. I have received so many punches. But I’m so excited that I don’t feel pain. I just perceive a vague ringing in my ears.(Field note. 12 December 2016)

The ability ‘to listen’ to the conversation, as Patrick says, and achieve a “working consensus” about the legitimate violence bond the boxers together [93]. The field note shows that dealing with conflicting emotions—fear, excitement, aggressiveness—is a fundamental process in developing the attachment of the boxers towards each other and the group. Attachment is confirmed by the gesture of touching gloves, which is a sign of “respect” collectively excepted before and after every single duel [35], from an apparently insignificant first fighting experience to the toughest combat between expert boxers. As one of the coaches told me once: ‘we can easily break our noses. It’s fine when we share the same experience. This is respect!’

Working on the human emotions and experiential tension, sparring is also an exhibition of the individual qualities that produce and renew hierarchies within the gym. The nicknames of the boxers clearly embody this process. After a period of participation in sparring, the established members of the fighter clique that supervise sparring sessions give a nickname to the boxers. Every nickname expresses the individual ability in dealing with tension, as well as the corresponding position in the local structure. For example, ‘chicken’ and ‘gumby’ are two typical nicknames given to those who are scared by punches. ‘Gorilla’ and ‘boar’ are nicknames that refer to the boxers unable to control their aggressiveness. ‘Warrior’ and ‘killer’ classify the best boxers good at regulating the intensity of the confrontation according to the situation and able to knockdown, as well as to control and avoid this occurrence. For this reason, the nicknames put the boxers on top of the local hierarchy.

Because the “working consensus” of the fistic interactions is always the product of negotiation [93]—and injuries could occur at any point—sparring can violate the “upper threshold” of legitimate violence [87]. When the boxers are not able to limit the damage of their hitting according to the surrounding communication, moral reaction of the established can cause the exclusion of all those who are not aligned to the local rules and values.

‘Once I broke the ribs of a guy from another gym. He was fighting against Gianluca and he beat him like crazy… I mean, you punch strong three times; you hurt the opponent; the opponent shakes his body. So, why should you bruise his face continuously? What can a mother say of the swollen face of her son? If you are stronger, you must allow the opponent to conclude the round and respect the dignity of the person. That sparring was a training god damn it; it wasn’t a real fight. In addition, we are in the boxe popolare network. We don’t knockdown. We told him to stop and he didn’t […] I broke his rips on purpose in a punishing sparring. His coach told me: ‘oi, man. You crook his ribs!’. Fuck you, mother fucker. Do you want to show off your toughness in my home? You’re welcome!’.—Daniel

In the given example, the ‘punishing sparring’ serves to re-affirm the collectively expected conducts. The exclusion refers to the members of the CAPPA network belonging to another gym. However, the same mechanism works within the team.

During my fieldwork, only once a severe injury occurred: it happened to a newcomer that wore gloves that weighted 10 ounces and broke the left cheekbone of one well-known boxer. A few days later, a coach knocked down the guilty boxer in front of several practitioners. That person came back in the gym only a couple of months later bringing a new pair of 14-ounce gloves with him.

5.2.2. Technical Dispositions

Sparring can be considered a dispositif not only because it realises the very “conjunction of position and disposition” within and across the boxe popolare clubs [70] (p. 171). A second, crucial, socialising effect of the sparring is that of producing “conative dispositions”: they consist of “proprioceptic capacities, sensorimotor skills, and kinaesthetic dexterities that are honed in and for purposeful action” [70] (p. 173).

More than the other exercises, sparring forges the ability of taking and giving pain. To achieve this purpose, it is a consistent sparring routine that mainly restructures the physiology of the practitioners, his/her anatomy and perceptual skills.

‘You must learn how to breathe, control your heart rate, control the tension in your nerves, understand how much oxygen you have and how to govern your stamina. It’s so damn’ difficult. Many extra trained fighters are exhausted at the beginning of the third round: they are nervous and emotional, they don’t have enough oxygen to face the tension of the performance. You can get relaxed thanks to experience in sparring: sparring; sparring; sparring; and repeat’.—Patrick