1. Introduction

Powering community development (CD) requires an amplified level of community participation and empowerment [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Such an approach relies on an asset-based community development (ABCD) strategy which has gained purchase in most of Africa as an emerging development approach against the backdrop of the system’s perspective underpinned by assets and capabilities. The ABCD praxis is credited to the ABCD Institute, formerly at the Centre for Urban Affairs in Northwestern University in Chicago, which moved in 2016 to De Paul University in Chicago. According to its main proponents (Kretzmann and McKnight [

6], the ABCD is premised upon building up community assets and resources that already exist in the community through mobilization of individuals, associations, and other allied institutions [

2,

4,

6,

7]. The ABCD Institute identified six assets which include: 1. Individual resident capacities 2. Local associations 3. Neighborhood institutions –business, not-for-profit, and government 4. Physical assets –the land, everything on it and beneath it 5. The exchange between neighbors, such as giving, sharing, trading, bartering, exchanging, buying, and selling Stories [

6,

8]. While several studies have highlighted the role of assets in ABCD linked to CD [

4,

6,

8,

9], very few studies have emphasized the intersection of cultural assets and relational networking in CD within resource depleted communities of sub-Saharan Africa.

Essentially, this paper explores ways in which CD is being re-invented, with focus on cultural assets and relational networks deployed to provide much-needed infrastructure. This bottom-up development approach is embedded in the development trajectory of the Ndong Awing Cultural and Development Association (NACDA) in Cameroon’s north-west region. I engage with the intersecting elements of CD underpinned by cultural assets, matched with the propelling influence of relational networking. For CD to flourish, community capability, collective advocacy, social mobilization, and rebuilding social networks by fostering relationships across socio-economic differences are crucial [

3,

10]. It is contended that mass poverty can be scaled back through the empowerment of disadvantaged groups, taking into consideration the context of development practices [

11]. Cultural assets—tangible and intangible resources within the community, mostly under community hierarchy of traditional power, are habitually managed by the Fon (traditional authority) at the helm of the village [

12], in collaboration with village development associations (VDAs) which are community institutions championing grassroots development, created largely to fill the gaps in infrastructure [

1,

13]. Cultural assets both visible and invisible enable the community to build on its capability. Such assets are accessible to all members, while the support of partners is enlisted, ensuring the voice and participation of the community which is crucial for greater control [

14]. Prudent use of these assets offers communities greater leverage, fostered through conscientised empowerment [

3,

6].

Building on my previous research [

3], this paper interrogates whether utilizing cultural assets and relational networking incrementally, provides an arena for VDAs to execute CD initiatives. Infrastructure represents constructed amenities and facilities such as pipe-borne water, roads, bridges, community halls, schools, and health centers used collectively and catering for the wellbeing of the community [

1]. VDAs engage community members through a gamut of socio-cultural activities, such as annual cultural festivals, meetings, social groups, project development committees, diaspora linkages. Decision making is largely overseen by the VDA president in conjunction with members of project boards and committees and important decisions on funding are taken by presidents of operational branches/wards and relayed back to the general president and its executive bureau [

1,

3,

15]. Drawing from case studies and analysis of the NACDA, the process of galvanizing community members were scrutinized. The intertwined elements of cultural assets and relational networking marshaled to promote community development are laid out (

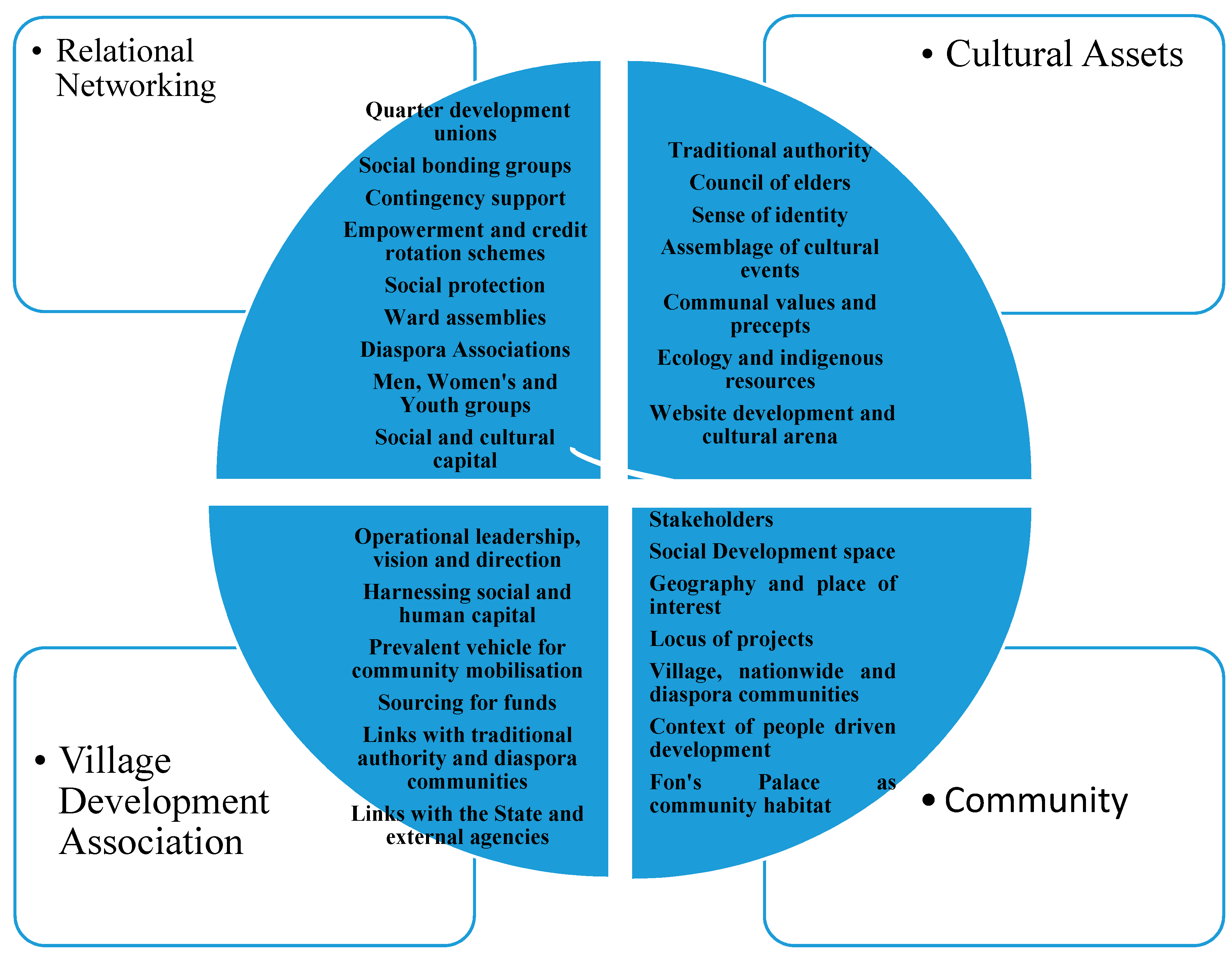

Figure 1). Such an approach ties in with rethinking CD from the bottom-up. It is anchored on defining the role of proactive citizens, and how they can work together with the main purpose of improving the well-being of their communities [

6,

16]. This strategy underpins the conceptual grounding of community development—a mutual process from everyday existence, understanding histories, cultures, and values, listening to the hopes and concerns of the community aimed at ushering in a process of empowerment and change [

3,

17]. A major outcome of Cameroon’s stagnating economy has been the crushing impact on vast segments of its rural population, who are trapped in decayed and weak infrastructure. This has subjected many, particularly those without access to income, to unprecedented levels of economic and social dislocation, exacerbated by institutional failings and government dithering [

18]. Yet, there is little investigation into the deployment of relational networking to fill the gaps in infrastructure provision through needs identification and local solution-focused strategies.

With an estimated population of over 21 million, Cameroon is an ethnically and geographically diverse country with more than 280 ethnic groups and dialects. As a result, social structures and systems of authority vary across ten different regions. There are perceived tensions between traditional systems of governance and the state administrative apparatus. Cameroon’s economic situation is exacerbated by the growing inability of the state to respond adequately to the growing development concerns and essential needs of rural communities. Community participation has been advanced, and in fact tried, as a strategy that can be potentially viable in complementing government efforts to meet community needs [

19].

The NACDA has a track record of operationalized wards and development assemblies, amplified through strategic leadership and capacity building, a prevalent approach to grassroots development in Cameroon’s north-west region [

3,

13]. The foundational elements of community development are perceived through the prism of relational networking and utilization of cultural assets by VDAs, creating a people-oriented and outward-facing community. Case study evidence in tune with recent research on the subject area underpins the elements of relational networking and cultural assets, calibrated for a meaningful CD (

Figure 1).

While these elements are crucially important in CD initiatives, implementation lags, hampered by intersecting factors must be proportionately balanced to fulfill the potential of community-driven development (CDD). For the NACDA to take charge of its development, priorities are set and agreed, and local solutions devised. Visionary leadership and a sense of community engagement championed by traditional authority and the leadership of VDAs are crucial. This strategy is anchored on mobilizing available assets through streamlined networking and partnerships (

Figure 1).

2. Conceptualizing Relational Networking and Cultural Assets

Community development occupies a contested space between top-down and bottom-up, which attracts many competing agendas [

17]; plural objectives and contested practices [

20,

21], which people experience as standard [

22]. Given the complexities inherent in engineering development in resource-poor settings, the theoretical literature situating agency, community empowerment and capability (strengths-based approach) are critical to understanding the contextual realities. A strengths-based approach (SBA) is an emerging approach in development practice to operationalize participatory development principles [

11,

23]. Other proponents of the approach emphasize a focus on both assets and strengths [

4,

7,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Reflecting the strengths and capability perspective, relational networking is grounded in human agency and the belief that change is possible, which creates a process of empowerment and agency [

28]. Agency is defined as ‘the capacity of persons to transform existing states of affairs’ [

29]. It is the ability to respond to events outside of one’s immediate sphere of influence to produce the desired effect [

30]. While social capital enables this potential, a keen sense of agency crystalizes this approach [

31].

In alignment with this notion of agency, it is argued that people demonstrate agency not necessarily for their own self-interest but in acting for a collective interest. It is thinking beyond the self in more narrow terms, showing consideration for the wider community [

32,

33]. The potential for agency serves as latent energy, unlocking the dormant potential in the human condition. Such potential becomes manifest when social conditions develop in a manner that calls for change and alternative perspectives. Although the agency may be visible at multiple levels—individual, group or through democratic participation [

34], the focus here is on community agency, members’ degree of interaction with others, enhancing community capability and sustainability.

From field data, it is evident that collective agency is vital for community development. The Awing maxim enshrined in the constitution highlights this commitment: ‘holding on to each other towards modernizing Awing’ [

3]. The community must be taken on board through a development-oriented mindset, conceptually framed as conscientised empowerment. We have argued elsewhere, that self-reliant development has proved its usefulness as an easy, all-onboard and results-oriented approach to contemporary modes of translating boardroom ideas into meaningful development [

35]. Relational networking can readily maintain both self and social empowerment when it is deeply rooted in the praxis of change. The use of cultural assets engineered by different actors (

Figure 1) is usefully deployed to galvanize community members. This is achieved through a carefully tailored narrative of development through reliance on inner capabilities and assets. This message is embedded in a speech by Awing Education Enhancement Fund (AEEF) president during the launch of one of NACDA’s flagship initiatives:

‘Let’s build our community and not wait on others to do it for us’ [

3]. The relational networking perspective espoused are informed by the community conscientization at the consequences of inaction. This strategy seeks to engage the community to consciously reflect and find local solutions to local problems of development illuminated in

Figure 1. This is in tandem with active citizenship, seen as individualized self-help or ‘do-it-yourself’ [

10].

Community agency represents a template of reflection on input and path of development driven by communities through local mobilization strategies and solutions to identified needs. In this context, CD is advanced through strategic leadership, and other stakeholders are mobilized, a crucial factor that fosters dynamic participation, building on community capabilities. The recognition of strengths is more likely to inspire positive action rather than a focus on huge problems that cannot be resolved. The logical consequences of focusing on assets and capabilities enable a proactive role for the citizen, replacing the passive, dependent role of the client in the welfare service delivery model of community development practice [

2,

11].

As embedded in

Figure 1, relational networking is underpinned by the community taking the lead, through active involvement in programmed social and cultural events, geared at solving identified problems and ushering in meaningful change within the community. Development outcomes are determined by the environment, and the gamut of natural resources or assets including individuals, associations, and institutions [

2,

6,

7,

36]. It is argued that focusing on strengths is motivating [

27], nurturing existing capacity and strengths will expand and contribute to a positive change process [

37]. Further, people take responsibility, initiative, and leadership, remain owners and directors of the change process. Mathie and Cunningham [

2] aver that communities can self-evaluate and drive the development process themselves. It hypothesized when this happens, then outcomes will be sustained, and people will become more self-reliant [

3,

35].

3. Methodology and Context

Contextual research, including observation, interviews, and case study research was employed to obtain local people’s perspectives [

38], informed by the perspective that community development should not be externally driven by the researcher’s objectives. In this light, a qualitative grounded theory method was deemed appropriate as it enables the researcher to construct theories to better understand phenomena [

39]. To capture the bigger picture, the case study approach examines the gate-keeping role, played out through cultural asset building and relational networking. Based on documented web evidence, elicited from the NACDA, connections are made between the agency, displayed by NACDA and internal stakeholders, particularly community members (CM). The alternative perspective is drawn from a random sample that takes cognizance of key actors, the context of community, strategic leadership, and participation of CM. The features, dynamics, and elements of agency displayed are unpacked with the theoretical literature.

Community members (CM) purposively sampled, numbering 67, were varied in age, gender, and educational and social backgrounds. The age ranged from 25 to 70 years of age, and educational background also varied. The leadership of the NACDA and other members constituted of youths and women were randomly selected. CM who participated span diverse sectors and were based in the village, other regions nationally and in the diaspora.

Mirroring the approach of CD from the bottom–up, the applicability of cultural assets and relational networking were scrutinized through an interview protocol developed in line with key questions and archival material obtained from NACDA officials. Other information gleaned from the interviewees were triangulated through follow-up interviews. Alongside the interviewing, a contextual coverage of NACDA 50th anniversary celebrations was validated with group discussions, which allowed community members to be directly involved in the research process. This helped to facilitate an understanding of the elements of cultural assets and relational networking. Furthermore, three government officials with expertise in CD were interviewed to get a snapshot of state relations.

Thomas’ [

40] knowledge-development research typology aligns with my chosen research methodology. This highlights the process approach, entailing describing and contextually analyzing the people’s development experience, rather than examining participation through a snapshot approach as in a quantitative study. Involving the participants closer to the research process is an attempt to understand their existence and actions within their world. This enables reflection, evaluation of change, and alternative perspectives within the mechanics of qualitative inquiry and research design [

41]. The participatory approach and group discussions in community development require: ‘An understanding that research problems are defined through a dialectic. This means a more ambiguous and shifting relationship between the research questions and the communities in which they are studied’ [

42].

Open-ended, semi-structured interviews were conducted, with a pre-determined number of questions, and the interviewees were freely allowed to elucidate on key questions as they envisaged. The average duration of each interview was 45 min to an hour. Some interviewees opted to speak in pidgin English which is a popular medium of expression in both rural and urban Cameroon. The transcripts were read over and codes applied, modified and revised in line with dominant and emergent themes [

43]. The stages of the methodology involved: (i) semi-structured interviews involving VDA officials and community members; (ii) follow-up interviews with participants; (iii) triangulated interviews with state officials and selected participants; (iv) data pieced together from VDA website and what resonated/differed from interviews, and (v) themes identified refined and synthesized in tune with comparable literature.

4. Emergent Themes and Discussion

NACDA, located in Awing village, north-west region, Cameroon was established 1962, in Buea, the south-west region of Cameroon. Currently, NACDA counts 63 branches (locally and overseas); women’s wing (25 branches); youth wing with 15 branches, and quarter development unions (9). In addition, it comprises other social networks (tax groups) operating nationally [

3]. The organization celebrated its 50th anniversary from November to December 2012. NACDA’s mission statement embedded in the constitution is unambiguous: ‘

Uniting around the self-reliant development of the Awing Fondom, creating an atmosphere of peace, promoting its diverse cultural and social acumen, and projecting a good image of the Fondom’.

Of vital importance in projects completed by the NACDA is addressing essential services such as water and electricity supply, health needs and educational requirements, thereby, increasing school attainment and enrolment rates, which are key social development concerns. The provision of basic infrastructure is undertaken in partnership with traditional authorities, overseeing decisions within traditional councils, thereby enhancing traditional governance, fostered through ward and chapter designated representatives.

As detailed in

Table 1, projects implemented included roads rehabilitation, equipping health clinics, providing essential textbooks for pupils, schools, funding payment of teachers hired through Parent Teacher Associations, building bridges and culverts, creating a fact book (database of Awing citizens), developing a cultural and web manifesto on development projects earmarked and to track of ongoing projects. These projects are implemented through a community schedule, overseen by officials of VDA in collaboration with traditional authority.

In fostering relational networking, the creation of mutual based schemes to improve educational attainment, health care requires the dynamic participation of women and youth groups. The foundational speech by the chairperson of the AEEF tunes in with a development narrative meant to enthuse, building on a community sense of fervent relations, mutuality, and sustainability. Such an approach fosters dynamic participation; a key marker of relational networking. According to Asnarulkhadi and Aref [

44] in a Malaysian case study, the mutual-help spirit that underlies the Asian traditional community spirit of working hastens the achievement of shared interests through group-based activities. The spirit of collective action in which members participate enables an understanding of group dynamics and processes within which participation takes place. Participation counters the reductionist perspective of community development. Basically, the application of values and principles of community development involves upholding or practicing human rights, and encouraging people to be self-reliant, to think, to make decisions and own them, and to participate in the entire process [

3,

35,

45]. As captured by AEEF chairperson, development begins with

‘sowing the right seed and spirit’ [

3]. This community spirited discourse needs to be harnessed for it to blossom and must be carefully managed to ensure sustainability.

Despite the workings of community engineered by traditional authority and VDAs, the prevalent thinking engenders a spirit of community ownership, sense of community pride to see its ‘mustard seed’ harnessed for the common good of the community, resonates with the empowerment drive. Relational networking in the context of Cameroon, where the politics of identity and ethnicity creates a hegemonic state [

15], is maintained by both the state, political elite, and citizens, networking through tribal affiliation. However, these forms of tribalism reinforce the sense of group identity and constitute attempts at the grassroots level to embed a development philosophy, built on trumpeting vibes that connect members. This energy and vibrancy are captured in remarks by the AEEF Chairperson: “

donor fatigue is what we want to avoid” [

3]. Such an inward-looking strategy is anchored on building social capital through a community agency approach, an a priori condition that manifests itself at both the individual and the collective level through social mobilization and network formation [

32,

33,

46], with focus on inclusive CD and a heightened sense of social justice.

5. Re-Calibrating Relational Networks and Cultural Assets

As highlighted in

Figure 1, traditional authority, VDA strategic leadership, community mobilization through sourcing for funds, diaspora linkages, social and cultural assemblages, and the inclusion of all stakeholders are vital components of relational networking and cultural assets building. The development drivers also include quarter development unions, women’s groups, njangis, health clubs, and other social development hubs. Women with crown titles ‘nkeum mengye’ (Fon’s senior wife in Awing tradition) investigate women’s concerns and are mandated to relay these concerns at traditional councils and general assembly meetings. In terms of leadership positions within NACDA, men hold top leadership positions while women are more active as chairpersons in women’s wings. Though there are no legal restrictions for women in holding key leadership positions, most women do not put themselves forward for senior leadership positions. This may be down to dominant cultural traditions and mindset that ascribes decision making to men [

1]. For example, in the NACDA general executive structure, 15 men hold top leadership positions, with only two women, while in the women’s wing, women occupy 25 key positions. NACDA officials indicate that in technical and project committees, there are 10 men and no women, seven men in quarter development unions and no woman while for branch chairpersons globally, there are 59 men and three women only [

3]. In fostering women’s empowerment, there is a NACDA women’s wing; a good arena for women’s issues to be factored into debates at general assemblies. In terms of power relations and the influence of patriarchy through men’s dominance of NACDA general executive [

1,

15], women are negotiating these relations of power as part of re-inventing CD by channeling their voices through NACDA assemblies, women’s enclaves and associational networks, the Fon’s senior wife ‘nkeum mengye’, who doubles as women’s emissary for the NACDA [

13,

47].

Rooted in the community mindset is the need to keep members active through upscaling social interactions. Interviewees noted that through the women’s empowerment centers nationwide, NACDA female members are pulled into cooperatives to market their goods. They are drilled on micro-enterprise development, skills development in cooking, sewing, business know-how. The centers also generate capital for small business ventures and pooled savings from women’s business activities. The viability of such small business and returns from empowerment centers permit members to make yearly contributions and donations to project committees for earmarked projects. The women’s wing also gives women greater leverage to undertake projects that address women’s specific needs [

3]. Approximately one-third of the NACDA development dues are plowed back into women’s wing. For instance, if a female member contributes 3000 frs CFA (Currency of the Central African Financial Community), one-third (1000 frs) is passed over to women’s wing (NACDA executive 2013). Both agency and empowerment are intrinsically valuable and instrumentally effective in reducing poverty and promoting human development [

34].

A member of the women’s wing intimated: ‘We’re trying our possible best to see that Awing village makes progress, by always paying our development levy as allocated’. Further, the president of the women’s wing said: ‘When I became chairperson in 2010, my main goal was to foster greater unity amongst women in Awing to work under one umbrella, to intensify their support for projects. The number of women attending meetings and taking an active part in NACDA activities has increased’.

She went further: ‘Apart from infrastructure development, also, we continue to sensitize mothers and our daughters on hygiene issues and diseases like malaria, cholera, and HIV/AIDs. We use gatherings to emphasize cultural norms and encourage women to take up leadership positions in NACDA’.

Interviewed on what makes NACDA successful in relational networking, an interviewee observed: ‘Women in NACDA have a strong voice. We have the opportunity all the time to initiate projects that address women’s concerns. The women’s wing is a very important arm of NACDA. It is like the door, and window of NACDA. Projects like health centers, social centers, and women’s empowerment centers mean a lot to us, so we try and raise funds to enable us to complete these projects as we learn a skill, share ideas on health and other aspects of everyday life’. Another member said: ‘As NACDA grows, we can beat our chests to say we were part of it and contributed to its growth. We have succeeded in repairing the roof of the women center in the village which was not in a good state’.

The importance of collective agency and active citizenship is not only enshrined in the Awing constitution but fostered through networking and other associational strategies of getting participants on board. An aspect of relational networking that inherently promotes the notion of active citizenship stems from providing social protection. An interviewee noted:

‘We feel a sense of citizens as people with an identity and a responsibility towards our community. Whatever we do, we are one people, and through our social groups and assemblies, we look out for each other. Community comes first. We protect the frail elderly and others who need help. During events such as deaths, births, we cry and celebrate together as one people’. As enunciated by Arnstein [

5], networking differs from partnerships and community control. While networking highlights areas of interaction and a shared sense of identity, partnerships relate to negotiated forms of collaboration and streamlined responsibilities. Community control is conceptualized through leverage and ownership, distinct from citizen control; a more representative process.

Community-led CD relies on strategic and visionary leadership. This remains the main driver of relational networking and echoed by a NACDA Official:

‘The president is like an umbrella to shade everyone, though there is a development vision, the president ensures that the NACDA vision is kept alive. The President works out how identified goals will be met and gets everyone on board’. Cultural assets are a key determinant of maintaining good community relations and engagement. The sustainable use of available resources for the benefit of the community is crucial. An interviewee stated:

‘Our plants, trees, water sources, and lake have to be used wisely, so we can all benefit from it and our children as well. Some of us survive by drawing palm wine, this enables us to sell, and be able to pay our community levy.’ Cultural assemblage constitutes a leeway of getting members active in different wards. During such occasions, food and dances are on the menu of social activities within different wards and branches. An interviewee captured this: ‘

I look forward to the weekly cultural meetings as we are able to share our local food together. Members bring in different food items, and we all partake; the food, dance, and sharing are also a good way of not forgetting our roots, and traditions’. Seen as a cultural asset, and reinforced through members undertaking projects in micro relational networks, the quarter development unions, headed by a branch coordinator provides an arena for members to showcase their talent and expertise by pushing forward the development vision of NACDA [

3,

13]. An interviewee noted:

‘We see the quarter development union as another way of hastening the implementation of development projects. This links in with the bigger plan of projects. From the smallest units, we can better mobilize to achieve the bigger NACDA goals’. From the diagram (

Figure 1) VDAs intersect with the community, and then relational networks are re-energized, cultural assets mobilized on an incremental basis, to promote genuine bottom-up development, underpinned by strengths, capacities, aspirations and hopes, particularly of women and young people. Individuals, associations, institutions, physical assets, exchanges and stories that bind them are vital arteries of the community [

6].

Such assertions above tie-up with the enabling aspect of empowerment according to Labonte and Laverack [

14], and this implies that people cannot ‘be empowered’ by others. They can only empower themselves by acquiring more of power’s different forms. Craig [

48] defines empowerment in the community development context as: ‘The creation of sustainable structures, processes, and mechanism, over which local communities have an increased degree of control, and from which they have a measurable impact on public and social policies affecting these communities’. While cultural assets are influential, issues around power, leadership roles and male dominant traditions must be addressed as it this can impact on community relations and levels of participation.

External Partners and Agencies

NACDA thrives on a mentality that development is first and foremost locally driven before ‘knocking on the doors’ of external partners and other development agencies. Partnerships are initiated with external development partners such as the British High Commission, the Swiss, German embassies, and other Diplomatic missions in Cameroon. Such external partners constitute a multifaceted approach of relational networking steered by the visionary leadership of NACDA. At NACDA’s 50th anniversary, the erstwhile British High Commissioner to Cameroon, Bharat Joshi, who was in attendance, underscored the relevance of inward-looking development:

‘Only you can make your country an emerging economy by 2035. We can only help, but we can’t tell you how to do it’ [

3].

Fostering relational networking is hinged on strategic leadership within different layers of local authority, in synergy with the elected officials of the association, and other development partners. The NACDA constitution underlines the centrality of the traditional authority (Fon and traditional council), working in tandem with the VDA officials to get projects initiated, and completed (

www.ndongawing.org) [

13]. Further, the different wards of NACDA undertake development tasks, based on delegated responsibilities, from the hierarchy of the village association. In return, elements of cultural assets are utilized to galvanize community members, as a recognition for their input in CD. The conferment of traditional titles and other accolades is considered as symbolic recognition for international partners who have assisted either with funds, or other forms of expertise in the implementation of NACDA projects [

13]. On behalf of the Swiss Government, the then Swiss Ambassador to Cameroon, Uli Berner, was knighted by the Fon of Awing with conferment of the traditional title

‘mbah-ntiante’ (an organizer) for the Swiss Embassy’s support and injection of funds (4.6 million Frs CFA), towards the Awing water project [

3]. The utilization of these multilateral relational strategies in combination with cultural assets, as stated by Ledwith [

17] are attuned to collective action for change, which follows through from local to structural levels with sustainable outcomes.

From the explanations of participants, the reliance on strategic leadership is crucial in building a community spirit of mobilization. However, lengthy discussions and coordination between the different antennas of the VDA create managerial challenges. An interviewee opined: ‘

Communication can be very slow between branch presidents. They are not reachable by email frequently to move urgent matters on’. Another interview was concerned with the time span for implementing projects from conception: ‘

It is hard to know when projects would be completed as valuable time is spent in the follow of funds and pledges’. Added to this is the sluggish response of state officials, particularly with roads projects that require upfront authorization from central government and other local administrative officials. Irrespective of these challenges, the community draws on available cultural resources and networks to provide the much-needed infrastructure. A diverse human capital and social capital building are obligatory for the implementation of sustainable community development [

30,

32].

6. Policy Implications and Conclusions

Community agency, displayed through the utilization of relational networking and cultural assets incrementally, as argued in this paper have gained traction in indigenous polities of sub-Saharan Africa, striving to fill gaps in infrastructure provision. Community engagement and participation of local people in CD initiatives to provide basic services which affect their daily lives, represents the core principle of bottom-up, people-oriented development. It is contended that an autonomous model of empowering community members from acting as mere spectators to active citizens can build community resilience, and capability for sustainable CD endeavors, which respond appropriately to livelihood concerns, and community needs. The intersection of cultural assets and relational networks adds to the understanding of a grassroots modeled development, grounded in a holistic and solution-focused strategy which social policy and CD practice could benefit from.

Establishing links with the state, local government administrators, and other decentralized arms of the state machinery are important. The President of NACDA working in conjunction with traditional authority and community members can usefully rely on institutional backup while soliciting for funds and technical expertise for projects. Given that VDAs and the state are both conceptualized as institutions, the role of frontline government institutions like the Ministries of Public Health, Social Services, Education, Agriculture, and Rural development are crucial. For example, at NACDA’s 50th anniversary, the government official, speaking on behalf of the Ministry of Culture acclaimed NACDA’s grassroots development drive, offering a financial package (2 million frs CFA) noted: ‘

I want to express my congratulations to the job done by NACDA so far. You have contributed a lot to change the image and the lives of the people of Awing. We are behind you’ [

3].

A co-production of policies for CD and the deployment of key personnel and practitioners (social workers, health workers, welfare officials, and other development agencies) in collaboration with VDAs can enhance relational networking and better strategizing of cultural assets. Engaging with key stakeholders can expand spaces for participation, thereby optimizing cultural assets for social development [

12], although the ambivalent relationship between community work and state interventions can limit the potential of community development [

17]. Evidently, social workers and social welfare practitioners are of prime importance in enabling all stakeholders to leverage available resources, tapping into existing strengths, capabilities, and assets [

3,

4]. However, the challenge of remaking community development requires a multi-directional approach. Communities need resources beyond their reach. Development organizations, in turn, need the embedded knowledge and networks that communities can mobilize [

49].

Relational networking and cultural assets reinforce the sense of mutuality, community cohesion, and ownership in community development ventures. The community vision is kept alive through benchmarking progress, ensuring the development vision is sustainable, based on careful calibration of multifaceted and multi-layered relations with internal and external stakeholders. A heightened sense of community networking enables members to give back to the community, thereby enhancing social development in resource-poor and disadvantaged communities. Utilizing resources within the community aligns with the capacity-focused development pathway, emphasizing community building through reliance on available assets and networks [

6]. As the interview quotes indicate, CD is being re-invented, underlined by a core principle—a people-oriented community leads to a people-oriented development. Leveraging the duality of cultural assets and relational networking is premised on a community sense of recognizing its own strengths and pulling together for infrastructure provision. Community members are mobilized to re-invent and focus on their assets and resources, rather than concentrate on deficits and barriers. The foundational thesis of relational networking and cultural assets rests solely on mobilizing community resources on an incremental basis, drawing out the strengths of citizens, rebuilding social networks, which are key to re-inventing community development. The operational structure and workings of the VDA are crucial in rebuilding networks and utilizing cultural assets to provide much-needed community infrastructure.