1. Introduction

In the context of social design and sustainable futures, it is essential to listen to citizens and apply tools that can capture the complexity of their lived experiences [

1]. When societies are shaped based on people’s real needs and desires, the likelihood of fostering health and wellbeing increases [

2,

3]. Co-design not only supports more inclusive and responsive design outcomes, but also generates emotional value—such as identification, motivation, and engagement—that transcends purely functional benefits [

4,

5,

6]. Yet, despite increased attention to participatory processes, one significant group—children, who make up 21% of the total Swedish population—is often overlooked in decision-making [

7].

Promoting health through citizen engagement is particularly critical given current challenges in Sweden’s healthcare system. The country faces a growing care debt, where demand for care exceeds system capacity. According to Sweden’s municipalities and regions [

8], the number of children aged 0–17 in contact with child and adolescent psychiatry services (BUP) rose from 6.2% 2021 to 7.4% in 2023 in Sweden. While a 1.2% increase may seem modest, in absolute terms, it represents 26,115 children, equivalent to more than 1000 full school classes. This striking figure underscores the urgent need for proactive approaches to child wellbeing. But how might such proactive strategies be meaningfully developed?

One promising approach is grounded in psychological wellbeing and the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which identifies three basic psychological needs as crucial for wellbeing: autonomy, competence, and relatedness [

9]. Autonomy refers to experiencing agency and alignment with one’s own goals and values, thereby fostering motivation. Competence involves feeling capable and effective, enhancing engagement. Relatedness captures the sense of connection and belonging, which underpins overall wellbeing. A meta-analysis by Ntoumanis et al. [

10] confirms that SDT-based interventions can positively influence health behaviors and physical and psychological health. In fact, autonomy is increasingly recognized as a top-level outcome in healthcare, aligned with patient wellbeing and social justice.

The current study applies design methods that engage the senses to explore how individuals—particularly children—experience and envision their environments. Human perception and decision-making are shaped not only by rational thought but also by sensory input and emotion [

11] where perception can be seen as the bridge between the environment and the body, continuously changing in different contexts [

12]. Emotional and sensory-based design methods can thus play a key role in identifying sustainable solutions and motivating change. Children, in particular, are known to be sensory-oriented, constructing knowledge through embodied, hands-on experiences [

13].

This research aims to explore and exemplify how sensorial design methods can support the development of autonomy, competence, and relatedness among children and young people. It explores how tools such as sensory walks and stimulated recall (sensory recollection) can yield new insights into the design of public spaces, particularly from children’s perspectives. First, we describe the methods used in workshops with fifth- and sixth-grade students, aged 12–13 years old. We then present their sensory-based reflections on the journey to school, along with their design proposals. Finally, we summarize the key findings and offer insights into what matters when designing with and for children.

2. Sensory Co-Design

Co-design is a research and design approach that emphasizes collaboration between designers and non-designers in the development of ‘things’ such as products, services, and environments [

5,

14]. When applied in the context of children, co-design becomes a tool for inclusion and also a means of acknowledging children as competent social actors with valid perspectives on their own lives [

15,

16,

17]. Co-design is not simply about producing efficient or functional solutions, but about addressing controversies, engaging with plural perspectives, and attending to the messy entanglement of social and material life [

18]. By involving children as co-designers, rather than mere users or informants, the design process becomes richer, more grounded, and more ethically aligned with their rights [

19].

Design is, in this context, not only a cognitive or conceptual process; it is also a material practice. According to Ingold [

20], materials are not passive substances to be shaped by the designer, but active participants in the thinking and making process. This aligns with the notion of material thinking, where engagement with materials is fundamental to the emergence of ideas [

21,

22]. In co-design, where the aim is to enable participants—often non-designers—to contribute meaningfully, the choice of material becomes crucial. Material act as mediators of dialog, helping participants externalize, test, and transform their ideas in tangible ways [

5,

23]. The tactile and sensory qualities of materials—whether soft, rigid, malleable, or colorful—can evoke emotions, associations, and memories that would not emerge through verbal discussions alone [

5,

24]. Involving children, for instance, often requires open-ended, playful, and familiar materials that invite experimentation and reduce pressure to perform [

25]. Thus, selecting appropriate materials can significantly influence how participants engage, what they express, and how they understand both the design context and their own role within it.

Furthermore, a growing body of research highlights the importance of multisensory engagement in design and co-design processes. Sensory design goes beyond the visual to include sound, touch, smell, and movement, fostering embodied interactions that are especially relevant for younger users whose ways of knowing are often tactile, affective, and experiential [

26]. Akner Koler, Billing and Göran Rodell [

27] explore how haptic models can enhance design thinking by expanding sensory awareness, showing that engaging touch and embodied perception supports creative processes in collaborative and cross-disciplinary design contexts. Children’s engagement with space is inherently multisensory and acknowledging this can improve both their spatial experience and emotional wellbeing [

28,

29,

30].

In design research with children, sensory methods can be used to explore how they perceive and evaluate their surroundings. Techniques such as sensory walks, sand sensory mapping [

31,

32], and creative making (e.g., drawing, clay modeling, AR/VR prototyping) [

5] allow for richer expressions of children’s embodied knowledge. These methods show potential in making visible the everyday emotional and sensory experiences that often remain invisible in traditional planning and evaluation processes.

Yet, engaging children in sensory reflection is not without its challenges. While vision is often the most accessible and commonly discussed sense, other modalities—such as sound, smell, or touch—require more deliberate prompting and interpretation [

33,

34]. Research shows that children may initially struggle to articulate non-visual experiences, but with supportive facilitation and tools, they can provide deep insights into how these sensory cues affect their sense of comfort, safety, and enjoyment [

13,

30].

From an ethical perspective, co-design with young participants must be sensitive to power dynamics and developmental stages. Building trust, creating safe and playful environments, and valuing non-verbal expression are essential to ensure meaningful participation [

30].

Embodiment and multisensoriality is central to how humans experience and make sense of the world, yet they remain difficult to fully capture through conventional research methods. Merleau-Ponty and Smith [

35] emphasize that perception is grounded in the body, arguing that we humans come to know the world through lived, bodily engagement rather than detached observation. In design and ethnographic research, scholars like Pink [

31] and Ingold [

20] have highlighted the importance of attending to sensory and embodied practices, yet they also note the methodological complexity of doing so. Sensory experiences are often fleeting and subjective and resistant to verbal articulation, requiring creative and interpretive methods, such as sensory mapping, visual diaries, or haptic models, to make them accessible [

20,

27,

31]. As a result, researchers must adopt flexible, multimodal approaches that recognize the partial and constructed nature of any representation of embodied experience. Combining co-design methodologies with sensory approaches, however, can enable a more inclusive, empathetic, and grounded design process, one that recognizes children as users of space and as active agents in shaping the future they inhabit.

3. Materials and Methods

The empirical material for this study was gathered through a series of four workshops conducted with children. The first workshop was conducted in May 2024 with a group of 7 fifth-grade students, aged 11–12 years. The subsequent workshops took place in September and October 2024 with the same group of students and their classmates, a total of 34 students now in sixth grade. All workshops were held during regular school hours as part of the student’s “student choice” curriculum, in collaboration with their teachers.

Phase 0: Planning and preparation

The planning and preparation phase of this co-design workshop series was essential to ensure that the activities would be both ethically responsible and pedagogically engaging for the young participants. Drawing on principles from co-design and child-centered design methodologies, the process focused on creating a safe, inclusive, and stimulating environment where children could meaningfully contribute their perspectives on mobility and public spaces.

Before initiating the workshops, formal consent procedures were developed in line with ethical guidelines for research with children [

36,

37]. Written consent was obtained from legal guardians, and children were informed of their rights as participants, including the freedom to withdraw at any time. An ethical review from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority [Dnr 2024-01339-02] was conducted prior to the project due to the collection of possibly sensitive personal data.

A partnership was established with teachers and school staff to integrate the workshops into the regular school schedule, specifically during “student choice” sessions. This collaboration helped to ground the workshops in children’s everyday routines, making participation feel natural rather than imposed [

28]. Teachers also acted as key support during the sessions, helping to scaffold the activities and ensure that every child could engage comfortably.

The workshop series was also carefully sequenced to build up from personal memory (recollection) to physical experience (sensory walk), imaginative ideation (analog co-design), and digital exploration (AI and VR co-design). This program followed pedagogical principles of scaffolding and gradual immersion, helping children move from familiar to unfamiliar modes of engagement [

38].

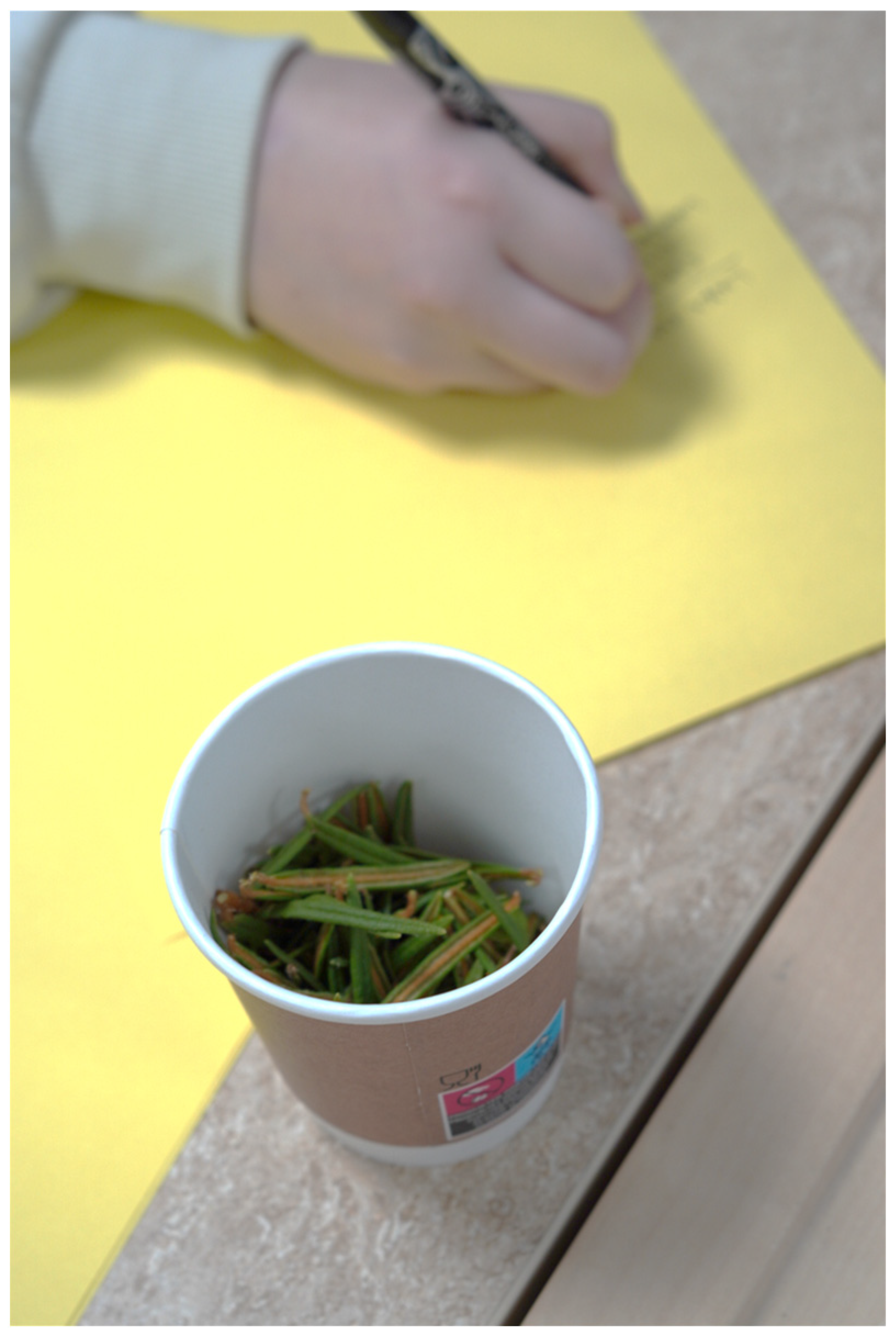

Special attention was given to material selection, as materials play a vital role in enabling thinking-through-making in co-design contexts [

6,

39,

40]. Tactile, visual, and interactive elements, such as colored pens, Post-its, clay, sensory sticks, and cameras, were chosen not only for their accessibility but also for their ability to stimulate multisensory exploration and creative expression.

In line with sensory ethnographic methods [

31], sensory prompts were prepared to help children reflect on sight, smell, sound, taste, and touch in their school and everyday environments. Prototypes, sound clips, tactile materials, and visual tools, including large canvases and seasonal images of school routes, were developed to support non-verbal communication and storytelling [

30].

The project team also have extensive experience and expertise in co-design methods and child engagement. Pre-workshop sessions were held to align on roles, language use, and moderation strategies, ensuring that interactions remained respectful, responsive, and open-ended. The team adopted a facilitative rather than directive role, encouraging children to explore their experiences freely while providing structure and follow-up questions to support deeper reflection.

Workshop 1: Memory recall

Settings and participants

The first workshop took place at a primary school in Luleå, Sweden, and involved seven 5th-grade students—four girls and three boys—aged 11–12 years during Spring ‘24. The children were selected by the school from two different classes within the same school. The workshop was facilitated by two PhD candidates from Luleå University of Technology: one from the Department of Architecture and one from the Department of Design. Stimulated recall methods were chosen for their ability to elicit detailed, reflective accounts from participants [

41].

Procedure and materials

The 90 min workshop began with a brief introduction where facilitators introduced themselves, explained the role of a researcher, and engaged the children in a discussion about what research means and what researchers do. This created an inclusive and dialogic atmosphere, in line with child-centered methodologies [

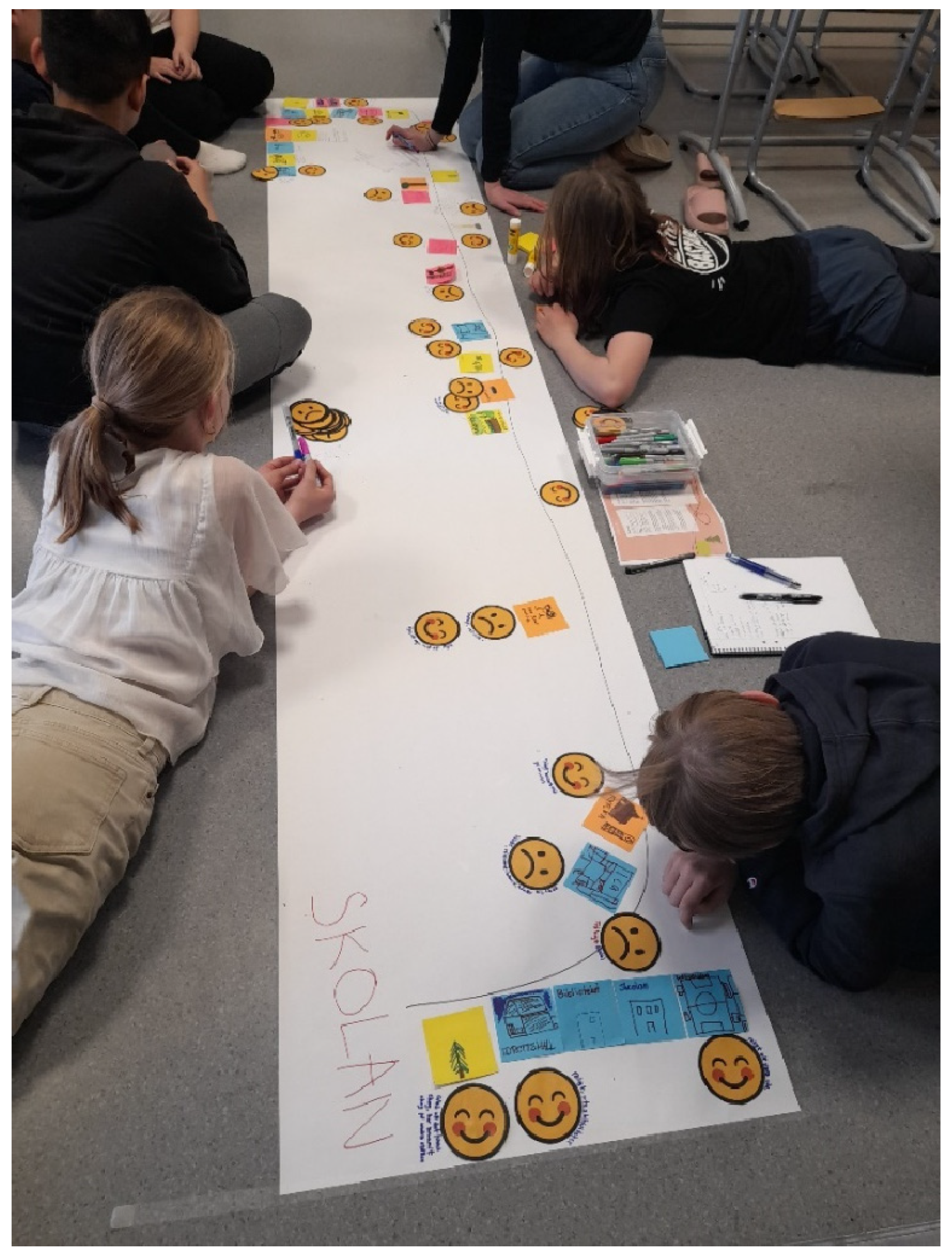

28]. A long sheet of paper was unrolled across the floor, with the word Hemma (Home) written on one end and Skolan (School) on the other.

The participants were then asked to recall and share their experiences from the journey to and from school. They documented their memories by drawing and writing short narratives on Post-it notes, which they placed along the large paper timeline (

Figure 1). The process encouraged interaction and collaboration among the participants, as they discussed their experiences and added new memories inspired by each other’s stories. The researchers facilitated the session by asking follow-up questions that helped the children elaborate and reflect further on their travel experiences.

Evaluation of experiences

After mapping their experiences, the children evaluated each recalled memory as either positive or negative. They used pre-printed smiley face stickers—happy or sad—to indicate their emotional responses to each memory. These were affixed next to the corresponding Post-its (

Figure 1). Facilitators then followed up with open-ended questions such as ‘why did this moment feel good or bad to you?’ or ‘what would make it better?’ Their answers were documented directly next to the visual material. This multisensory and multimodal approach—combining drawing, storytelling, dialog, and visual–emotional mapping—allowed children to express their experiences in varied and accessible ways [

32].

The workshop concluded with a reflective discussion, where the children shared their thoughts on their current mode of travel to school, including perceived advantages and disadvantages. As a token of appreciation for their participation, each student received pencils and erasers, enough to share with their classmates.

Workshop 2: Sensory walk

Setting and participants

This workshop was attended by the same seven students from the previous session—now in sixth grade—along with one additional classmate, bringing the total number of participants to eight. The facilitation were again two PhD students from Luleå University of Technology, now joined by two professionals from the behavioral design consultancy Beteendelabbet, adding further interdisciplinary expertise to the session.

Workshop process

The workshop began with an activity designed to heighten the children’s awareness of their senses. To explore the relationship between taste and smell, participants sampled different juices while blindfolded and holding their noses. This playful experiment encouraged reflection on how their sensory information influences perception.

Following this introductory exercise, the children were divided into four pairs and each group was provided with a custom-designed sensory toolkit. Each kit included the following:

- ▪

An instant camera (Instax) for capturing sensory impressions visually;

- ▪

Five sensory sticks, each representing one of the senses (sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell);

- ▪

A “thumbs up” and a “thumbs down” stick to indicate positive or negative experiences;

- ▪

Paper and pens for notetaking and drawing;

- ▪

A “mind enhancer” element—either a blindfold or earmuffs—to alter or restrict one sense and provoke reflection on how this changes perception (

Figure 2).

This multimodal toolkit was designed to encourage embodied exploration and reflection through guided, playful interaction with their environment.

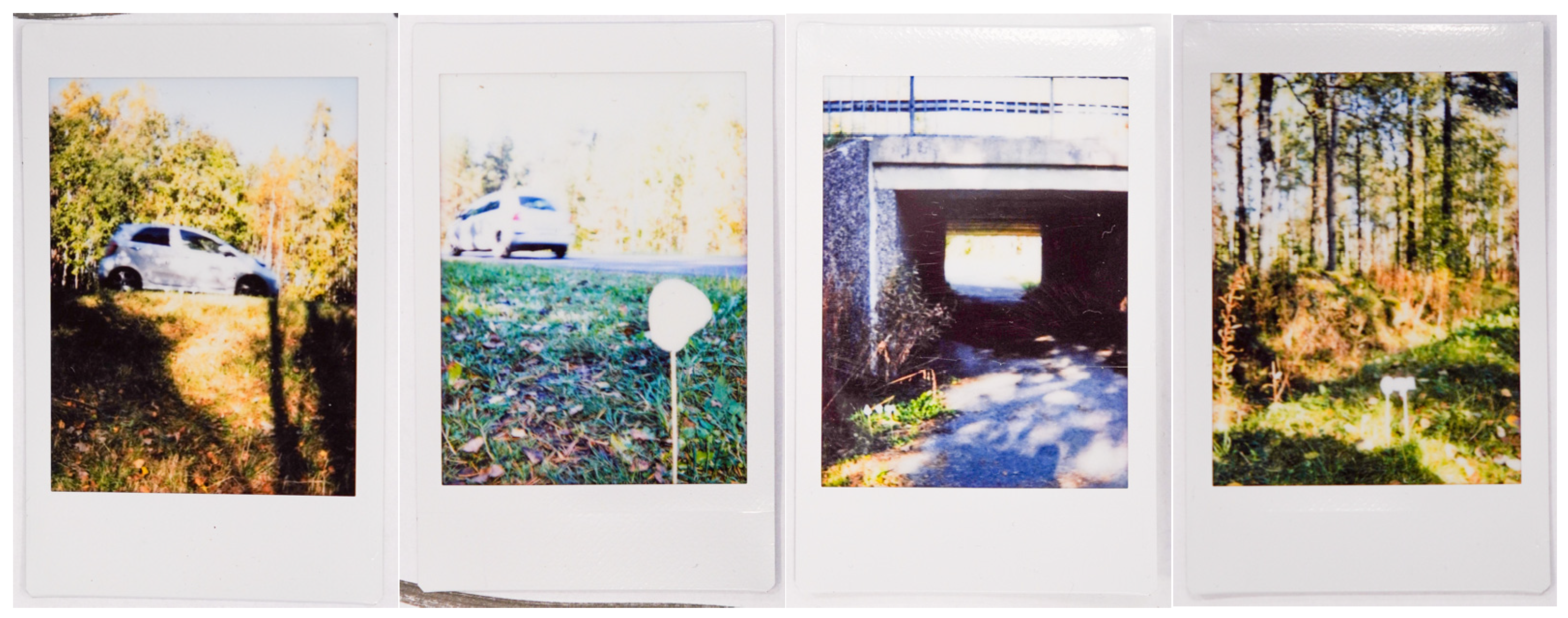

The group was instructed to walk along the school route and document any sensory impressions that stood out to them, whether visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, or gustatory (

Figure 3). When the children encountered something along the route that stood out or “popped”—that is, captured their attention—they were asked to identify which sense had been stimulated and to evaluate whether the experience was positive or negative. They then documented the moment by taking a photograph, accompanied by the relevant sensory and evaluative sticks (

Figure 4).

After completing the walk, all groups reconvened at the school. A large sheet of paper was rolled out on the floor, and the students collaboratively arranged their photographs in chronological order, reconstructing the journey (

Figure 5). Each group was then invited to elaborate on the sensory impressions associated with each photo, explaining which sense or senses were activated and whether the experience was perceived as positive or negative and why.

Workshop 3: Analog co-design

Setting and participants

For this workshop, in early Autumn ’24, all students from the two 6th-grade classes were invited to participate, resulting in a total of 34 participants of mixed gender. The facilitation team consisted of the same two PhD students from the earlier workshops, now joined by a professor in design from the same university. The workshop was conducted on-site at the student’s school, in close collaboration with their two teachers.

Workshop process

The session began with a brief introduction to revisit the previous workshops and set the stage for the current activity. The students were then divided into seven smaller groups.

The first activity focused on the sense of smell. Each group was presented with three distinct scents: blueberry soup, a local aromatic plant known as Skvattram (Labrador tea/

Rhododendron tomentosum), and vinegar (

Figure 6). The children were asked to smell each sample and reflect on what it reminded them of and how it made them feel.

The second activity engaged the sense of hearing. Students listened to three pre-recorded soundscapes: traffic from a busy road, birdsong, and the sound of water being poured. For each sound, participants were asked to describe what they heard and to discuss the emotions or associations the sounds evoked.

The aim of these exercises was to heighten the children’s sensory awareness beyond the visual, encouraging a more holistic and embodied engagement with their environment.

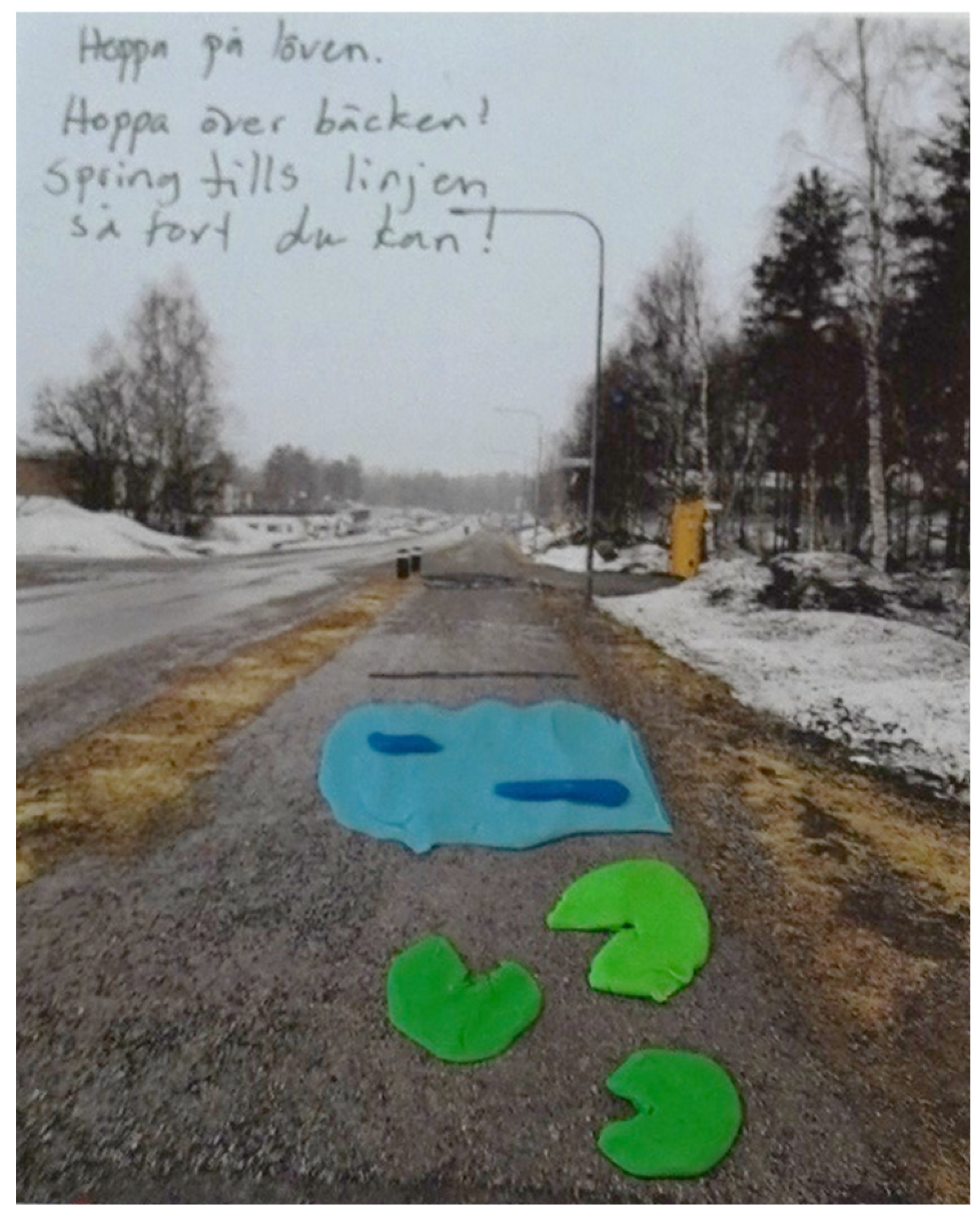

The next step involved exploring four key focus areas commonly encountered along the student’s route to school: tunnels, green or forested areas, pedestrian crossings, and shared pedestrian/cyclist paths.

Each group was provided a large sheet of paper displaying images of one of the focus areas—shown in both winter and summer conditions—along with a range of creative materials including colored pencils, Post-it notes, modeling clay, and colorful pipe cleaners, (

Figure 7). Working with one focus area at a time, the students engaged their senses to imagine improvements and possibilities. They were guided by questions such as the following: What would you like to see? How would it smell? What textures would you like to feel? What sounds would you want to hear as you walk or cycle past? The aim was to encourage multisensory thinking and inspire ideas that would make these areas more appealing and enjoyable on their way to school (

Figure 8).

After approximately 60 min of creative work, each group had explored two of the designated focus areas. The facilitators then invited the students to present and explain what they had created, describing their ideas and the sensory considerations behind them. The workshop concluded with a brief evaluation activity, where students responded to a simple feedback questionnaire with the following statements: “This was fun!”, “This was okay!”, and “This was less fun!”; this allowed for a light-touch reflection on their experiences.

Workshop 4 a and b: Digital co-design with AI and VR

Place and participants

This workshop was conducted over two separate days during Autumn ’24, with each of the two 6th-grade classes participating on a different day. The first class included 19 students and the second 18, totaling 37 participants of mixed gender. The facilitation team consisted of PhD students from Luleå University of Technology, civil servants from Luleå municipality, and a senior lecturer in Architecture from the university.

The workshop took place in the children’s own classrooms at their school. The digital tools used were Urbanist AI for generative design and PACE-SEED for creating and navigating virtual environments.

Workshop process

Students were first divided into two main groups, which were then split into smaller subgroups. Half of the class began by working with AI, while the other half started with VR. Midway through the session, the groups switched tools to ensure that all students had the opportunity to work with both technologies.

The overall structure of the workshop mirrored that of the previous analog co-design session. However, instead of using physical materials, the students used digital tools to visualize and design ideas for the four focus areas along the school route: tunnels, green/forest areas, pedestrian crossings, and pedestrian/bike paths. The aim was to explore how emerging technologies could support children’s creativity and multisensory thinking in the context of urban design.

The AI activity began with a group brainstorming session, during which the students reflected on what elements they wanted to include in their design suggestion for the four focus areas. Working collaboratively, they developed descriptive keywords and phrases to use in their AI prompts. Once satisfied with their ideas, they input the prompts into the Urbanist AI software and observed as the tool generated visual design proposals (

Figure 9).

The base images used in the AI software were the same seasonal photographs previously introduced in the analog co-design workshop (

Figure 8). After reviewing the AI-generated outputs, each student selected their preferred image and explained the reason behind their choices, offering reflections on why the design appealed to them.

The VR component of the workshop began with a short introduction of virtual reality, including a discussion about the students’ existing knowledge and experience with the technology. Following this, the participants brainstormed ideas on how they would like to improve or redesign aspects of their local urban environment. The VR experience was presented via a computer-based interface that featured pre-scanned 3D images of the student’s actual school route and surrounding areas (

Figure 10). This allowed them to navigate the familiar environment digitally, walking through the space, exploring elements they appreciated, and identifying aspects they would like to change.

As in the previous workshop, the session concluded with a brief evaluation using the same feedback questionnaire: “This was fun!”, “This was okey!”, and This was less fun!”. Since this was the final workshop in the series, students were also asked a few overarching evaluation questions to reflect on their overall experience of the project and its various activities.

4. Results

The outcomes of the four workshops were compiled and shared with the local municipality responsible for the school’s surrounding area. The material will be used as a foundation for the municipality’s Child Impact Assessment, ensuring that children’s perspectives and rights are integrated into future planning and decision-making processes. The following sections contain a synthesis of the key findings, followed by a summary of the outcomes from each workshop.

Workshop 1: Memory recall—experiences of the school route

In the memory recall session, the young participants were asked to reflect on their daily journey to school and document their experiences using Post-its, drawings, and storytelling. A total of 25 experiences were recorded, of which 11 were positive, 8 negative, and 6 neutral (see

Appendix A for a full list).

- ▪

Of the 25 experiences, 11 were associated with specific locations such as bus stops, playgrounds, apartment buildings, the local church, the school itself, a grocery store, the library, a soccer field, and a tunnel.

- ▪

The remaining 14 experiences were related to objects or events, including trees, vehicles, gravel, a trampoline, a mast, an owl near the sea, a kissing couple, and preparatory cabling for a streetlamp.

One notable negative experience involved a communication mast located in the forest. The child described the sound it emitted as disturbing and frightening, stating the following:

“It sounds scary—like it could be war in Sweden.”

(Young participant, workshop Spring ’24, Author’s translation).

This comment highlights how children interpret sensory inputs not just physically, but emotionally and imaginatively (

Figure 11).

Another example of negative or mixed experiences was associated with the local grocery store. One child described it as a place where “a lot happens sometimes” (Participant workshop Spring ’24, author translation). This illustrates how everyday public spaces can be perceived as emotionally charged or unpredictable from a child’s perspective.

In contrast, positive experiences were often linked to a sense of curiosity, comfort, or excitement. For instance, the sight of preparatory wiring for future lamp posts was interpreted as hopeful:

“It makes me happy that something is being built there.”

(Young participant, workshop Spring ’24, authors’ translation).

Another student recalled seeing an owl by the sea, describing the moment as both joyful and calming:

“It’s fun to see an owl–and also nice to see the sea.”

(Participant workshop Spring ’24, authors’ translation).

These reflections highlight how children’s experiences are shaped not only by functionality or aesthetics, but also by emotional, temporal, and imaginative dimension (

Figure 12).

This workshop showed that children’s memories are grounded in multisensory perceptions and often tied to specific emotional responses. Their reflections revealed both practical observations and deeply felt associations with everyday spaces.

Workshop 2: sensory walk

For a detailed overview of all experiences documented during the sensory walk, see

Appendix B. In total, the children captured and photographed 23 distinct sensory experiences, of which 13 were evaluated as negative and 10 as positive. The experiences were categorized according to the senses they engaged:

Sight (14 Experiences)

- ▪

Negative (7): These included abandoned electric scooters, litter, dull pedestrian crossings, and intrusive car traffic.

- ▪

Positive (7): These included graffiti, the construction of a new bath house, wild blueberries, forested areas, playgrounds, and greenery.

Hearing (5 experiences)

- ▪

Negative (5): All related to disruptive or unpleasant car noise.

- ▪

Positive (0): No positive auditory experiences were reported.

Smell (2 experiences)

- ▪

Negative (1): A tunnel with an unpleasant odor.

- ▪

Positive (1): The fresh scent of grass.

Taste (4 experiences)

- ▪

Negative (0): No negative taste experiences were reported.

- ▪

Positive (4): All associated with wild blueberries found along the path.

Touch (7 experiences)

- ▪

Negative (3): These included the effort required to navigate around obstacles or a feeling of unsafety when crossing roads.

- ▪

Positive (4): These included feelings of safety, excitement about new developments, and associations with positive memories.

Throughout the walk, four recurring environmental zones were particularly noted by the children: tunnels, green/forest areas, pedestrian crossings, and shared pedestrian/bike roads. These emerged as shared sensory hotspots: spaces where experiences were either particularly pleasant or unpleasant. Additionally, certain landmarks stood out. One such example was the construction site of a new bath house, which evoked a rich multisensory response: touch, sight, and even imagined taste (

Figure 13). One student explained,

“It’s fun that they are building a nice bath house, and it will be done in December. Nice that something is going on–and when it’s done, you can feel the water.”

(Young participant, workshop session Spring ’24, authors’ translation).

This workshop confirmed that children experience urban environment in layered, multisensory ways, and that positive feelings are often tied to change, play, nature, and sensory richness, while negative feelings are connected to noise (see

Figure 14), dirt, disrepair, and a lack of safety or stimulation.

Workshop 3: analog co-design

In this workshop, children explored and co-designed ideas for improving four key areas along their school routes. Below is a summary of the design suggestions that emerged from their collaborative and generative work.

Tunnels: Currently, tunnels are perceived as unsafe and unpleasant. Children described issues such as bad smells, poor lighting, and litter. However, tunnels were also acknowledged for their practical benefits: they eliminate the need to walk near traffic and offer shelter from the rain. To transform tunnels into safe and welcoming spaces, the children suggested the following:

- ▪

Adding color through murals or painted surfaces;

- ▪

Installing better lighting;

- ▪

Regular cleaning and maintenance.

Green Areas/Nature: Nature was generally experienced as positive and uplifting, with flowers and birdsong contributing to what students described as a “cozy and fun” atmosphere. However, there was a desire to further enhance these spaces through

- ▪

Brightly colored elements;

- ▪

Wooden animal figures;

- ▪

Uplifting messages displayed on signs.

Pedestrian crossings: Children expressed a strong desire for safety and clarity at pedestrian crossings, while still wishing for them to feel lively and engaging. Suggestions included

- ▪

Incorporating plants and sounds of birds to make the space feel more natural;

- ▪

Using bold colors to increase visibility and add playfulness;

- ▪

Clear signaling for when it is safe to cross, which would also make the space feel more welcoming.

Pedestrian/Bike paths: Children envisioned these routes not just as functional corridors but as spaces of play and engagement. They proposed adding interactive features to make the journey more enjoyable, such as

- ▪

A “playful side of the road” with balance lines or games painted on the path (see one example in

Figure 15);

- ▪

Rainbow colors or decorative patterns to make the environment more fun and stimulating.

This workshop revealed that children’s visions for public space balance safety, sensory richness, and playful expression, reflecting a holistic and emotionally attuned approach to everyday mobility.

Workshop 4a and b: digital co-design

The design proposals created through the AI and VR workshops primarily focused on enhancing the existing environment through the addition of vibrant colors, lighting, and personal touches (

Figure 16). Students expressed a strong connection between aesthetic improvements and emotional response. As one participant noted,

“When it’s colorful and has lots of light, the space feels safe, cozy, and it makes you feel happy.”

(Participant, workshop Autumn ’24, authors’ translation).

Another student reflected on the emotional durability of beautiful spaces:

“When something is nice and beautiful, you can look at it for a long time without getting fed up–and you want to go there.”

(Participant, workshop Autumn ‘24, authors’ translation).

The children’s designs were influenced by seasonal references—such as Halloween decorations and Christmas lights—as well as personal interests, including hockey, soccer players, and favorite animals. These choices reflect how children incorporate both cultural context and individual identity into their vision of inclusive and engaging public spaces.

This workshop demonstrated how digital tools like AI and VR can amplify children’s imagination, enabling them to visualize ideas that combine functionality, playfulness, and emotional resonance.

Reflection on the workshops

The students expressed a high level of enthusiasm for the workshops, describing them as an enjoyable and refreshing break from their regular school routines. Many found it inspiring to be involved in an urban design process, highlighting how the experience gave them new perspectives on their everyday surroundings, particularly the routes they travel daily.

One student commented that the workshop helped bring the class closer together, while another enthusiastically stated,

“This is work, but fun work.”

(Participant, workshop session Autumn ’24, authors’ translation).

Overall, the feedback emphasized that the children enjoyed the opportunity to design, create, think critically, and collaborate with one another.

Knowledge sharing and municipal use

The insights and design proposals gathered from the workshops were compiled and delivered to Luleå municipality, where they will serve as a foundation for a Child Impact Analysis. This analysis will inform the planning and development of a future city district in Luleå, ensuring that children’s voices and sensory experiences are meaningfully integrated into urban decision-making processes.

5. Discussion

The workshop series offered valuable insights into how children experience, interpret, and reimagine their everyday environments when given tools and space to do so. In this section, we reflect on the key findings from the workshops, considering both the opportunities and challenges of engaging children in sensory-based co-design. We discuss how the use of multisensory methods supported deeper emotional and spatial understanding, the nuances of children’s feedback, and the broader implications for urban design, planning, and participatory research with young people and how it connects to the three basic psychological needs crucial for wellbeing—autonomy, competence, and relatedness [

9].

Engagement and emotional impact

This series of workshops was experienced positively by the participating students and contributed to a strong sense of relatedness and inclusion. The activities offered an enjoyable break from traditional classroom learning but also gave children a rare opportunity to engage meaningfully in urban design processes. Several students highlighted how the project helped their class connect more deeply as a group.

Children found joy in being listened to, creating, and cooperating: elements that fostered emotional investment and reinforced the importance of designing participatory methods that are playful yet purposeful. This aligns with the SDT [

9] and the three core needs to create psychological wellbeing. The sensorial design methods helped to explore the children’s goals and values in relation to their school routes, enhancing the autonomy of the children. With the help of senses, the children could stop, stay, and explore their experience, making their design input more connected to what they truly want and need. The multisensorial methods functioned as tools for the children to express and explore their emotional and sensorial experience which connects to and develops their competence since they could use different materials such as photographs and clay, finding a way to explore and explain their experience that suited them best. The co-design workshop series created a sense of connection and belonging referring to the core need relatedness, since they could take this journey together with their classmates, developing their bonds with each other in an open and playful way and creating a sense of belonging.

Multisensory awareness and design implications

A key insight from this study is that using the senses as an entry point allows children to express and reflect on their lived experiences in rich, embodied ways. By tuning into what smells, sounds, or colors made a place feel inviting, or unpleasant, participants were able to express nuances of place that are often overlooked in adult-centric planning.

However, the workshops also revealed asymmetries in how senses are processed and expressed. Visual experiences were more easily articulated, while sound and smell proved to be more complex. For example, although birdsong was occasionally mentioned, it was rarely documented, while car noise was consistently identified as disruptive.

Similarly, functionality was not enough to ensure positive experiences. A tunnel may be useful, but if it smells bad or is filled with litter, it becomes an unpleasant place. These insights reinforce the need for aesthetic and sensory quality to be seen as essential—not secondary—in urban planning and design for and with children.

Learning through the senses

The workshops began with sensory warm-ups such as blind smell tests, encouraging students to reflect on how different stimuli made them feel. This was challenging at first: students found it easier to identify a smell (e.g., “citrus” or “woodsy”) than to articulate the emotion it triggered. Negative reactions were easier to express than positive ones. Over time, however, many of the young participants became more comfortable staying with and describing their emotional responses, especially when supported by follow-up questions from facilitators.

Perception of urban environment

Children displayed a high level of spatial and social awareness, especially in relation to change and construction. For example, they noted the positive anticipation around a new bath house or street lighting project but also expressed frustration at detours caused by construction sites. What may seem like a temporary inconvenience from a planner’s perspective may span a significant portion of a child’s school years, shaping how they feel about their living environment. Even if the children were 12 years old, they experienced nostalgia. Objects such as a large painted stone evoked positive memories and positive feelings, making it important to explore what is important when developing their urban environment. Working together with municipalities, the need for co-design methods is large, particularly when developing plans with children. Using the senses is something that many can relate to which makes the method clearer and easier to use. It also offers a way to stay in the experience and explore the task using the spectrum of the different senses. The senses can also be represented in many ways, making it easier to adapt to different groups of participants.

Challenges and future directions

The young participants approached the workshops with openness and enthusiasm, and with remarkable creativity, often combining materials like modeling clay and printed images to express their ideas (example in

Figure 15). Their reactions were unfiltered, and emotional responses, especially to smells, were often vocal and energetic.

However, several challenges emerged that suggest opportunities for refining the method:

- ▪

Capturing sensorial experience: Co-design with the help of the senses helps the participants to stay in the context and explore it from different angles in a clearer frame. A challenge is to be able to translate the perceptual into something we can express and describe to someone else [

12]. Combining sensorial exploration and creative methods such as using clay, taking pictures, etc., may be a way to reach that experience while being aware that this is only a reflection on that true experience from within. Being able to stay in that experience and try to express and capture it is a skill to continue developing.

- ▪

Feedback collection: While many children in fifth and sixth grade are capable writers, writing may not be their preferred way of sharing ideas. Richer feedback was often obtained through oral storytelling and small group discussions, where ideas could be built collaboratively.

- ▪

Rating scales: The simple positive/negative smiley system used for evaluating sensory experiences was generally effective but could be improved by adding a neutral or mixed-option emoji, allowing for more nuanced responses.

- ▪

Touch as sense: The sense of touch was underexplored, and children often interpreted it as känsla (feeling/sense in English) rather than känsel (tactile touch in English), a distinction that may be blurred in the Swedish language. This suggests a cultural–linguistic aspect worth considering in future studies. A greater emphasis on hands-on materials or haptic tools could help deepen engagement with this sense.

- ▪

Technology choice: While cameras worked well for documenting visual impressions, sound received less attention. Future workshops could include audio recorders or sound diaries to capture and reflect on the soundscape more effectively.

- ▪

Voluntariness and participation: Since the workshops were conducted within the school setting, participation was not optional. While this ensured inclusivity, it may have created a sense of obligation for some children. Future iterations could experiment with open calls or opt-in formats to better balance inclusiveness with voluntariness.

- ▪

Fairness as a social value: Interestingly, fairness emerged as a recurring theme, not only in relation to design but in how materials were distributed or when groups finished in different times. This highlights how social dynamics within co-design processes should be considered alongside the physical environment being explored.

- ▪

Sustainability and bio-diversity: The study explored how the children experienced their living environment, and this can be used in the urban decision-making processes, making the decisions more targeted and thus more sustainable. Another way to embrace sustainability even more could be to add a spectra of bio-diversity into the process since nature is important for wellbeing.

6. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated the value and potential of engaging children as active co-designers in the design of their everyday environments. Through a series of workshops that integrated memory recall, sensory walks, analog prototyping, and digital tools (AI and VR), children were invited to reflect on their experiences and also to reimagine the spaces they navigate daily. Their responses reveal a capacity for critical insight, creativity, and emotional depth, underscoring the importance of designing with, not just for, young citizens.

One of the most significant contributions of this study is the emphasis on multisensory engagement. By focusing on how environments look, sound, feel, smell, and (occasionally) taste, we gain a richer understanding of what makes a place feel welcoming, safe or stimulating for children. The workshops showed that while functionality is important, aesthetics, sensory richness, and emotional connections are equally crucial in shaping children’s perception of a place.

The results also highlight that negative sensory stimuli, particularly unpleasant sound and neglected spaces, often override positive features such as nature or play. This insight is essential for urban planners and policymakers who aim to create health-promoting and inclusive environments. Children made it clear that even temporary changes, like construction noise or visual clutter, can have long-term impact on how they feel about their neighborhood.

Importantly, the findings emphasize that co-design is not only possible but highly effective when appropriate methods are used. Children responded most enthusiastically when they were invited to explore, build, and share ideas in open-ended, hands-on, and socially collaborative formats. However, the study also identifies areas for methodological improvements, such as refining sensory tools, introducing audio-based methods, and balancing inclusivity with voluntariness.

The materials from this study have been shared with Luleå municipality as input for their Child Impact Analysis for upcoming urban development. In doing so, this research bridges practice and policy, showing how child-led design processes can meaningfully contribute to more just and sustainable urban futures.

In conclusion, involving children in design is not simply an educational exercise; it is a democratic act that brings valuable knowledge into decision-making processes. If we are serious about designing sustainable futures, we must make space for children’s voices, imaginations, and lived experiences at every stage of planning, development, and maintenance.

Mobile phone use

Mobile phone use

Electric kickbike

Electric kickbike

Wooden plank

Wooden plank

Roadblock

Roadblock

Bath house

Bath house

Pedestrian crossing

Pedestrian crossing

Blueberries

Blueberries

Blueberries

Blueberries

Blueberries

Blueberries

Cars

Cars

Forest edge

Forest edge

Tunnel entrance

Tunnel entrance