1. Introduction

This paper advances a form of critical design thinking, as a hybrid approach that brings critical, reflective, and provocative design practices [

1] into participatory, real-world contexts such as NHS Scotland. NHS Scotland is the publicly funded healthcare system in Scotland and one of the four systems that make up the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. NHS Scotland consists of 14 regional NHS Boards which are responsible for the protection and the improvement of the population’s health and for the delivery of frontline healthcare services. Design HOPES, an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded design-led research initiative comprising five Scottish Universities, NHS Scotland, the third sector, and design organisations, aims to catalyse change through strategic co-designed interventions that challenge assumptions, involve diverse voices, and reframe design-led projects of healthcare sustainability. Design HOPES is a transdisciplinary research project that exploits the potential of design-led thinking and making to innovate and tackle multifaceted health delivery challenges to meet urgent Net Zero goals for a sustainable health and social care system. In the following sections, the paper describes a range of ongoing projects that all aim to create strategies to support the green transition including the reduction in waste, increasing energy efficiency, and designing sustainable practices. But these projects also demonstrate how these changes can lead to greater well-being for NHS Scotland staff and patients, with improved quality of life, healthier ways of working, and greater efficiency. All of these projects utilise novel methods and tools to support design thinking, making, and (importantly) acting in addressing Net Zero transformational change across NHS Scotland hospitals.

The paper presents Design HOPES’s work that is driven by the needs of the UK’s public sector who require urgent research and innovation involving academia, industry, third sector, and publics to design new visions for sustainable health and social care that foregrounds people, places, products and policies that are predictive, preventive, personalised and participative. Design HOPES, supported by multi-stakeholder partners including businesses operating in the design economy, public-sector health and social care organisations responsible for large scale products and services, and third sector organisations, has identified and defined a series of aims and objectives, through these partnerships, to:

Empower design-led research to respond to significant green transition challenges in innovative, design-led collaborative ways;

Embed circularity and sustainability across the design and development of new product, service, strategy and policy design in response to real-world issues;

Realise measurable, green transition change across sectors and publics with real-world benefits and impact;

Catalyse and foster opportunities for social, cultural, environmental, and economic impact of design research-led interventions;

Enable and support a greater diversity of voices and perspectives in the design of green-transition interventions, including users, publics, next generation design talent, and underserved communities;

Create opportunities to build capacity and capability in design research for green transition challenges across and beyond the health and social care ecosystem;

Promote the role(s) of design-led research and practice across health and social care, and foster new opportunities for innovation in designing green transitions.

Design HOPES’ creative and novel approaches to data collection, analysis, and interpretation has encouraged NHS Scotland staff to provide deeper insights and more nuanced responses about their everyday working practices and environments. The Design HOPES’ design-led interventions will have utility in wider design research projects where fostering a culture of collaboration, co-creation and design innovation is paramount. Several of the Design HOPES’ projects described in this paper have utilised Pop-Up installations to prompt and gather feedback from NHS Scotland staff in their working environments, drawing on the work of Candy and Potter [

2], Dunne and Raby [

3], Durfee and Zeiger [

4], and Ballie and Bruce [

5], who have recently described these Pop-Up installations as ‘Design Imaginariums’ suggesting that the “…concept holds the promise of catalysing societal transformation. Through speculative design thinking and community driven creative problem-solving, these imaginative spaces serve as incubators for innovative responses to complex challenges…[thereby nurturing] a sense of community, equality, and shared responsibility.”

2. Context

The effects of climate change on health will affect most populations in the next decades and put the health and wellbeing of billions of people at increased risk [

6]. To put this into perspective, if healthcare were a country, it would be the fifth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases on the planet with the carbon footprint for healthcare being equal to the emissions of 514 coal-fired power plants, equivalent to 4.4% of global net emissions [

7]. So, the more we ignore the climate emergency the bigger the impact will be on health and the need for care with poor environmental health contributing to major diseases, including cardiac problems, asthma and cancer [

8]. At the same time, many of the actions to mitigate and adapt to climate change and improve environmental sustainability also have positive health benefits to such an extent that the Lancet Commission has described tackling climate change as “the greatest global health opportunity of the 21st century” [

6]. Our planet’s natural and built systems are inextricably linked to human health, and as such, the climate emergency poses a health emergency that must be addressed.

With around 4% of the country’s carbon emissions, and over 7% of the economy, the UK’s NHS has an essential role to play in meeting the net zero targets set under the Climate Change Act (Delivering a ‘Net Zero’ National Health Service) [

8]. Design HOPES’ focus, NHS Scotland, is the publicly funded healthcare system in Scotland, which has set an ambitious legally binding target for Net Zero to 2040. As a crucial contributor to meeting this 2040 target, NHS Scotland offers considerable design-led opportunities for a green transition. Design HOPES works closely with NHS Scotland and other partners and together they have the potential to scale and amplify successful design-led innovations to NHS UK and beyond through an international coalition of over 50 countries who have committed to developing low-carbon health Systems [

9].

The role of design-led research in health and social care contexts has changed in recent years, shifting from a focus largely on economic growth towards one of wider social and environmental issues that highlight a more design-led systemic approach. Many design researchers including several members of Design HOPES are involved in the sustainable design of interventions (i.e., products, services and systems) that positively impact on the environment, health and healthcare, promote dignity, and enhance quality of life, and action change in a range of settings [

10,

11,

12].

A recent review of health service design, delivery and improvement presented compelling evidence that a design-led systems approach to addressing health delivery challenges may lead to significant improvements in both patient and service outcomes [

13]. At the same time, the UK Design Council Systemic Design Framework [

14] provides support to designers, collaborating disciplines and sectors to create meaningful change. Design HOPES, part of Future Observatory, the Design Museum’s national research programme for the green transition funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, which is part of UK Research and Innovation, is a collaborative, design-led green transition ecosystem hub. It comprises five Scottish Universities, health boards across Scotland’s National Health Service (NHS), the third sector (charities, social enterprises, co-operatives, etc.) and other organisations from the design economy. Design HOPES will exploit the potential of systemic design-led thinking, making and acting to innovate and tackle multifaceted health delivery challenges to meet urgent Net Zero goals for a sustainable health and social care system.

The climate emergency is a health emergency and in response Design HOPES is creating, prototyping, and testing new products, services, tools, behaviours and systems needed for NHS Scotland to meet, and move beyond, urgent Net Zero goals that will create a sustainable health and social care system. In addressing this challenge, the paper asks how design can:

Reduce/eliminate waste in our healthcare systems?

Support healthier ways of living and working?

Help us see the bigger picture?

Change energy use and travel?

Involve and engage communities?

The contemporary design research landscape is a pluralistic one that comprises a rich range of methods, approaches, and tools that are inclusive, explorative, creative, critical and engender inquisitive attitudes [

15]. This pluralistic design research territory includes many perspectives and voices, which means many different ways of speaking. Ranulph Glanville reminds us that variety is crucial and we should be careful to guard different ways of thinking, exploring and writing about design and research, and we should value this variety while following our own design research journeys [

16].

The design research presented in this part of the paper describe examples of eight Design HOPES’ wide range of design-led approaches, tools and methods used in various contexts. The design-led methods presented here are not an exhaustive list, but they offer a small insight into the different approaches the authors have utilised in addressing real-world net zero issues in NHS Scotland contexts. The plurality, depth and richness of these illustrate the design thinking, making, and acting methods and tools the authors have developed. Here you will witness the development of mixed-methods and hybrid approaches, where the approach is on combining and/or appropriating established techniques from other disciplines with design methods and tools.

3. Design HOPES Projects

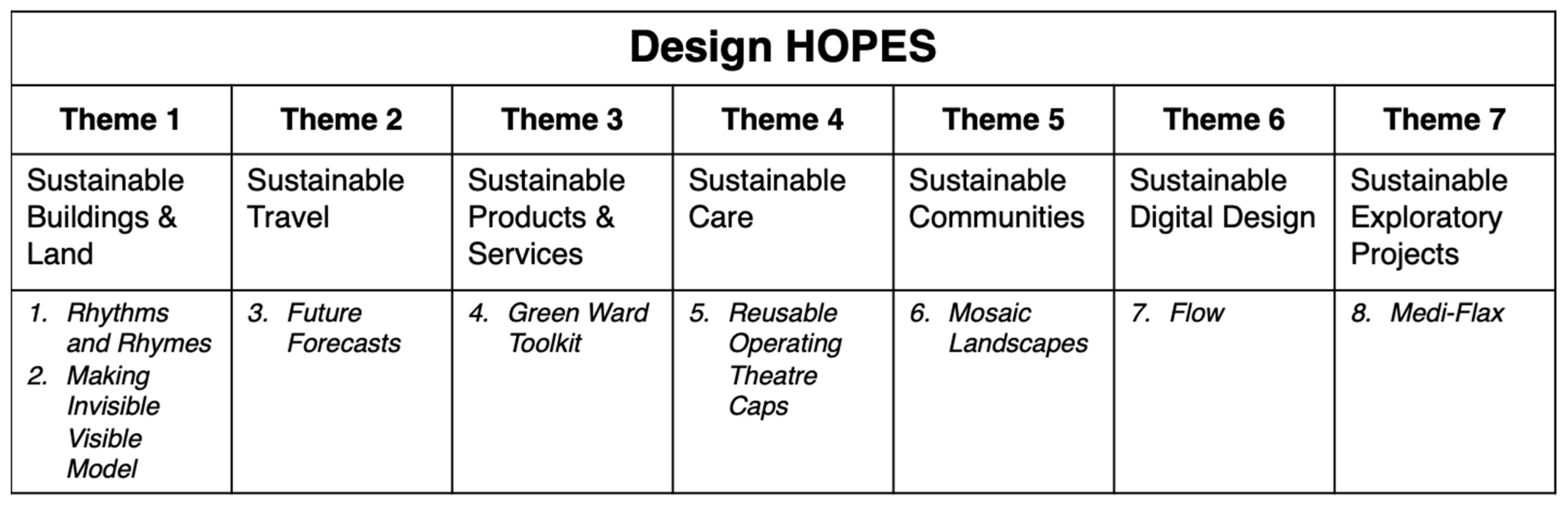

This part of the paper describes eight Design HOPES projects that illustrate the design thinking, making, and acting methods and tools used and the specific outcomes of the ongoing design-led research (

Figure 1).

These ongoing Design HOPES projects have been selected through a rigorous combination of stakeholder involvement where NHS Scotland, Scottish Government, and others working with the core Design HOPES team have explored, studied deeply what might work, assembled perspectives that are different from conventional ways of doing things (including from those that have historically been marginalised), reframed the problem and issues to support the transition to a regenerative world in a series of local co-design workshops and through more formal Design Sprints.

A Design Sprint is a time constrained process that allows teams to work intensively in testing goals, assumptions and requirements in relation to design problems, and in contexts where action and design research are being undertaken simultaneously that can accelerate the rapid production of prototypes, models and demonstrators that help develop design thinking, making, and acting [

17]. The four Design Sprints, based on the UK Design Council’s Systemic Design Framework [

14], took place with differing themes as the project progressed, moving from activities dedicated to problem exploration to design-led realisation, intervention, and impact as follows:

Explore—Study deeply and widely what is happening and actively draw in perspectives that are different from ours, including those which have historically been marginalised.

Reframe—Moving to a regenerative world means breaking out of our current way of thinking. We must reframe the problem in different ways for new ideas.

Create—Generate different actions and ideas that help people reimagine what might be possible.

Catalyse—Design is about making things. It shows people what a new future vision might look and feel like. It is important here to test how things work and to explore how they connect with other designed interventions.

The Design Sprints were formatted in such a way that the Design HOPES’ team was able to work within and across different themes, and appropriate expert input could be integrated within the sessions. This facilitated a sharing of knowledge, methods and approaches to tackle the issues that emerged. In short, this research has reframed the problems facing NHS Scotland in different ways to deliver new ideas.

The eight projects described in this paper are organised around the NHS Scotland/Scottish Government Climate Emergency and Sustainability Strategy core themes [

9]. These projects aim to deliver tangible outcomes such as new innovative products, services, and policies (e.g., sustainable theatre consumable products, packaging, clothing, waste services, etc.). Design HOPES comprises a rich interdisciplinary team with significant expertise in design and making, co-creation, health and social care, allied with professionals with a sustainability remit, and businesses working in the design economy.

3.1. Theme 1, Sustainable Buildings and Land

The overall aim of this theme is to develop assessment tools and protocols for enhanced delivery of healthcare incorporating knowledge on ways that the built environment impacts health. While healthcare practice currently incorporates diagnostics that involve tracing social determinants of health focused on the human body, they largely exclude the environments that humans inhabit (i.e., buildings). Evidence on the ways buildings impact global health and well-being is now well established [

18,

19]. In some instances, poorly designed, or inefficiently used indoor built environments have contributed to the onset of chronic health, social anxiety, and increased fuel poverty or tragically, even death. The economic consequences to the UK NHS budgets are significant, with the latest estimates predicting an increase of £1.5 billion per year for treating health conditions resulting from or impacted by cold, damp, overheating, poor indoor air quality amongst other indoor environmental conditions in buildings. While there has been extensive work in the built environment on ways to improve the design and operation of buildings as well as health consequences of indoor environmental conditions, there has been little advancement in healthcare practice. The two projects, Rhythms and Rhymes (

Figure 2) and Making the Invisible Visible, (

Figure 3) ask the following research questions:

How do healthcare practitioners perceive the home environment, specifically in reference to energy use and its impact on health?

How is air quality and air pollution communicated to advance understanding of health consequences?

What are the criteria needed in assessment protocols to ensure indoor environmental quality is considered in healthcare practice?

In exploring these questions, the projects have drawn upon design research methods including exhibition techniques [

20]. The two exhibits were installed in a hospital setting in Glasgow. The

Rhythms and Rhymes ‘dynamic’ exhibit was continually updated in response to healthcare practitioners’ engagement with the exhibition elements. The purpose of the overall research was to understand how healthcare practitioners perceive energy use in the home and the ways this impacts on patients’ health conditions. The complex nature of the questions, rarely considered in healthcare praxis, meant that traditional research methods such as interviews, focus groups or surveys would not have been as effective.

Drawing on over 300 responses from the Rhythms and Rhymes exhibit, thematic analysis showed that while healthcare professionals widely perceive home energy use—particularly heating as a significant determinant of health, this recognition does not consistently translate into clinical observation or action. Most respondents acknowledged these issues as important, and felt comfortable discussing social needs with patients, yet fewer reported routinely identifying or addressing energy-related factors in practice. Crucially, no respondents reported considering energy use in diagnosis or discharge planning. These findings point to a mismatch between awareness and embedded clinical engagement, with systemic barriers such as limited tools, institutional support, and professional role boundaries impeding consistent responses to energy-related home health concerns. Next steps for this project will involve consultation with a range of stakeholders including NHS Scotland, local government, NHS24, and public health experts to identify the essential components, delivery models, and institutional contexts for a home and health assessment protocol.

3.2. Theme 2, Sustainable Travel

The projects in this theme address a level of service and patient care which requires a significant amount of planned and unplanned travel, resulting in environmental impacts. A major question here is how can we start to understand, and change, the massive impacts of health-related travel and logistics?

NHS Scotland is the largest single employer in the country, with nearly 200,000 staff providing healthcare services in over 20 million hospital appointments each year across various clinical settings. Given the significant amount of planned and unplanned travel required for patient care, addressing the environmental impact of this travel is essential. To support NHS Net Zero targets, Design HOPES’ researchers are exploring sustainable solutions to reduce the carbon footprint associated with staff travel. This includes understanding the commuting behaviours of NHS Scotland employees and encouraging active travel as a means of meeting net zero objectives.

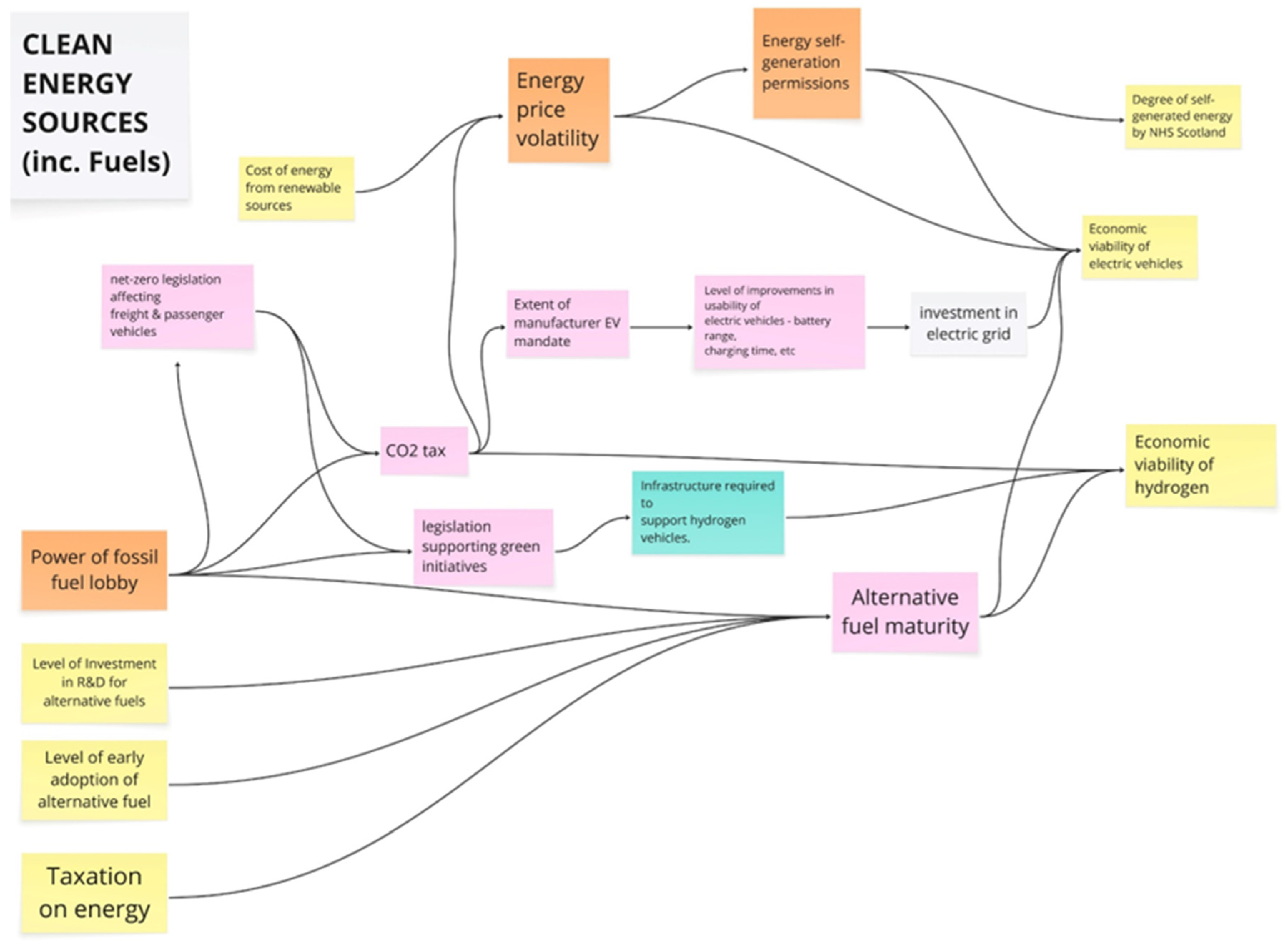

The

Future Forecasts project aims to reduce the environmental impact of all planned and unplanned travel associated with NHS Scotland’s healthcare system. For example, how might NHS Scotland’s transport fleet of ambulances and other vehicles produce significantly less carbon emissions (

Figure 4). This includes reducing the carbon footprint linked to NHS Scotland’s travel by increasing the efficiency of NHS Scotland’s vehicle fleet and promoting vehicle recycling. Additionally, this project aims to increase active travel and its associated health benefits by providing infrastructure such as showers and bike storage areas. The

Future Forecasts project asks the following research questions:

What are the current transportation practices across NHS Scotland?

How might we best facilitate the development of scenarios for the future of transportation across NHS Scotland by 2040?

What is the impact(s) of these scenarios on current NHS Scotland practices?

This research will lead to the creation of greater understanding about the status quo of NHS Scotland’s transportation and the factors that will affect it in the future. Working closely with NHS Scotland colleagues across various services, including clinical and professional areas, the researchers will co-create actionable recommendations on the transportation strategy of NHS Scotland.

3.3. Theme 3, Sustainable Products and Services

This theme explores ways to address unsustainable practices and behaviours in healthcare, with a particular focus on waste, proactive care, travel, energy, water and prescribing. A vital question in this theme is how can we adopt more sustainable practices to address barriers to engagement and progress in ward settings? The projects in this theme explore ways to drive systems and behavioural change by adopting the circular economy principles of redesign, reduce, repair, recycle and recover.

The co-design approach used in the

Green Ward Toolkit project involves assessing current approaches and diagnosing issues to identify new opportunities to improve practices in collaboration with clinicians, nurses, support workers, administrators, and other healthcare related professionals. In the early stages of this project, a pop-up installation (

Figure 5) was used to engage NHS Scotland staff at Ninewells Hospital in Dundee. Early research revealed that while many practice sustainability at home and understand its importance for NHS Scotland, they are often unsure how best to apply sustainable practices in the workplace. The

Green Ward Toolkit is designed to support both clinical and non-clinical staff by equipping them with the knowledge, skills, and resources needed to implement sustainable practices. By challenging norms, embracing circular economy principles, and raising awareness of innovative opportunities within ward settings, the goal is to cultivate a skilled and empowered workforce capable of delivering greener healthcare systems.

The

Green Ward Toolkit was further refined through an interactive research station (

Figure 6) where ward staff helped validate key themes and actions. Key features of the toolkit include:

A web-based platform to empower NHS staff in implementing new sustainable practices;

A speculative physical/digital device to display real-time carbon emission data to support behavioural change;

Case studies illustrating practical and feasible sustainable practices in healthcare;

A research-informed methodology to support the customisation and future integration of the web browser in a specific healthcare context.

In sum, the Green Ward Toolkit project aims to establish baseline data, change mindsets and drive behavioural change while leveraging design-led innovation to create scalable, sustainable solutions in NHS Scotland’s transition to Net Zero, ensuring a healthier future for both people and the planet.

3.4. Theme 4, Sustainable Care

This theme explores designing healthcare services that empower individuals, enhance health outcomes, and promote environmental sustainability. A key question in this theme is how can we embed environmental sustainability and health equality in all aspects of care? The design and delivery of care services play a vital role in improving health outcomes. However, these products and services face several challenges, including the increasing burden of chronic conditions, environmental sustainability, and health inequalities.

Projects in this theme explore the design and delivery of healthcare services, focusing on empowering individuals to take greater control over their health while developing rapid and enduring environmentally sustainable transformations.

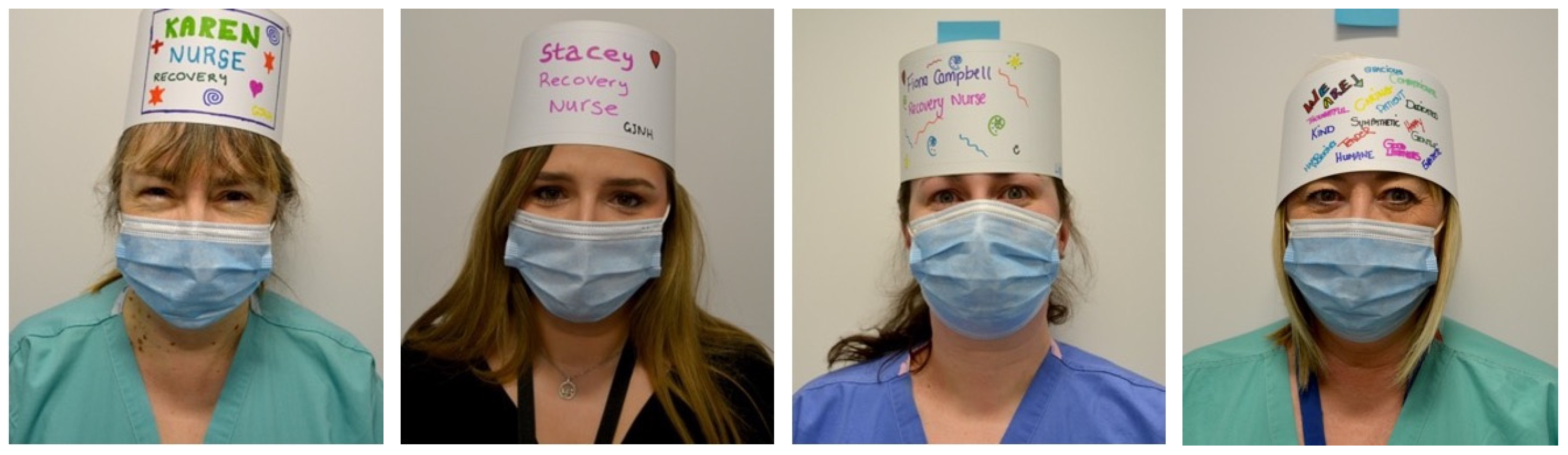

This theme is using a co-design approach, working closely with NHS Scotland theatre staff including surgeons, anaesthetists, nurses, and other healthcare professionals to design, develop, and evaluate plant-based Reusable Operating Theatre Caps, which highlight how effective design-led research improves both patient and staff experiences while eliminating waste and lowering carbon emissions. We are exploring ways to replace disposable single-use theatre caps with 100% sustainable and biodegradable reusable alternatives.

It is estimated that in 2023 a minimum of 110,557,119 (over one-hundred-and-ten million) disposable theatre caps ended up in landfill [

21]. Moreover, an average size hospital will dispose of around 200,000 single-use theatre caps each year. By introducing reusable caps across NHS Scotland hospitals, we will reduce waste and associated costs.

In close collaboration with theatre staff at NHS Scotland hospitals, we have co-designed a range of

Reusable Operating Theatre Caps that are personalised with each staff member’s name and role. This work has been undertaken collaboratively with hundreds of NHS Scotland theatre staff across a series of co-design workshops and using bespoke design research tools including cultural probes (

Figure 7), “quick-and-dirty” paper prototyping sessions (

Figure 8), and designing, making and user-testing physical mock-ups and prototypes (

Figure 9).

The tangible outcomes of this work not only eliminate waste (disposable theatre caps) but also improves patient safety, promotes better staff communication, and incident management. In addition to the clear environmental, economic, and patient safety benefits of these new plant-based

Reusable Operating Theatre Caps, this particular project has secured significant traction across UK media channels with over 200 coverage hits to date including

The Glasgow Herald [

22],

The Scotsman [

23], STV News [

24], key online sites like MSN, Yahoo, and current affairs titles such as

Perspective magazine and

Health Industry Leaders magazine.

The

Reusable Operating Theatre Caps have recently undergone manufacturing capability testing (

Figure 10) with a Scottish manufacturing company based outside Glasgow and are now gathering user feedback ahead of a larger production rollout across NHS Scotland. The caps will significantly reduce environmental and economic costs while enhancing patient safety and staff identification in operating theatres across the country. Future work planned includes further testing of the plant-based caps including laundry and biodegradation tests, and the creation of a start-up company that will design and manufacture the Design HOPES plant-based

Reusable Operating Theatre Caps in Scotland delivering vital socio-economic impact.

3.5. Theme 5, Sustainable Communities

The projects in this theme seek to foster mechanisms for NHS communities (e.g., NHS Scotland staff, patients, carers and other stakeholders) to coalesce around pressing healthcare issues and, in the process of co-designing and co-creating solutions, provide a route to active engagement focused on sustainability issues. In this theme, projects empower individuals to connect and collaborate as they help generate future healthcare solutions. A key question here is how can design research help engage communities in processes of change?

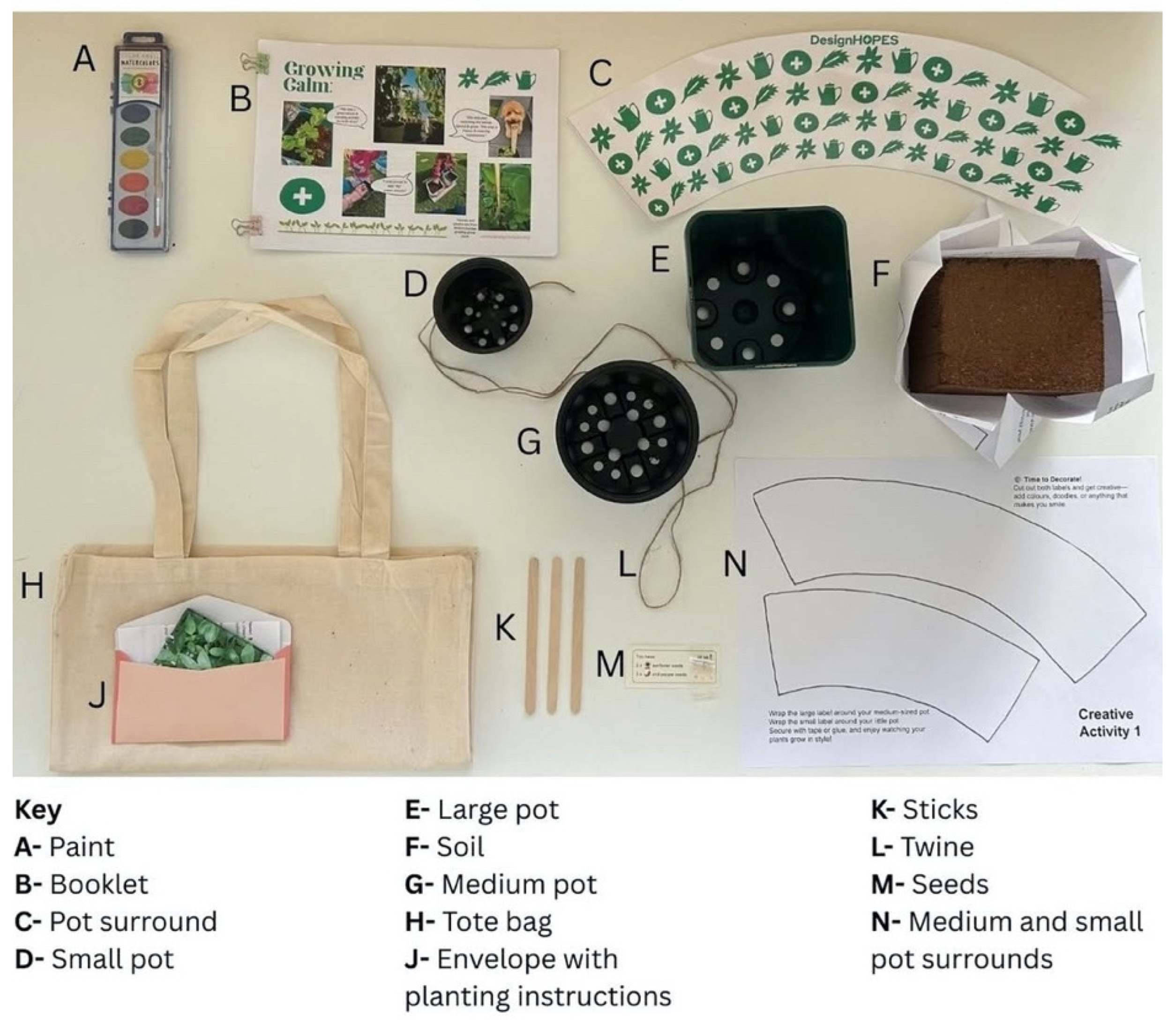

Researchers in this theme are working closely with Mountainhall Treatment Centre set in an area of green space within NHS Dumfries and Galloway. Working with local communities, the site is being co-designed to include a community food garden and restful spaces for people to connect to nature. This project uses design-led practices and bespoke tools to reconsider the use of green spaces in NHS Scotland estates, aiming to reduce loneliness, encourage more exercise, and boost well-being. The aim here is to empower local communities to get more involved in the design and delivery of these initiatives, including the production of locally grown, healthier food.

The design of physical spaces and services have a significant impact on health and wellbeing outcomes. Linking design research with behaviour change and understandings of place, this project is co-designing with citizens and healthcare professionals’ interventions that support health and wellbeing, resilience, engagement, and place-making in community settings such as the home-growing kit for NHS workers (

Figure 11).

Another project in this theme is the Mosaic Landscapes board game that engages communities in designing inclusive healthcare gardens to enhance health and wellbeing. Here, Design HOPES’ researchers are working alongside NHS Scotland partners to engage a range of different communities in the future of NHS Scotland land strategy.

Healthcare gardens are unique green spaces that support patients, caregivers, and healthcare staff by offering nature-based interventions proven to improve physical, mental, and social wellbeing. Situated within healthcare settings, these gardens can provide fitness and rehabilitation opportunities, mental restoration, and spaces for social connection. They can also foster innovation, such as growing materials for healthcare products or food for patients.

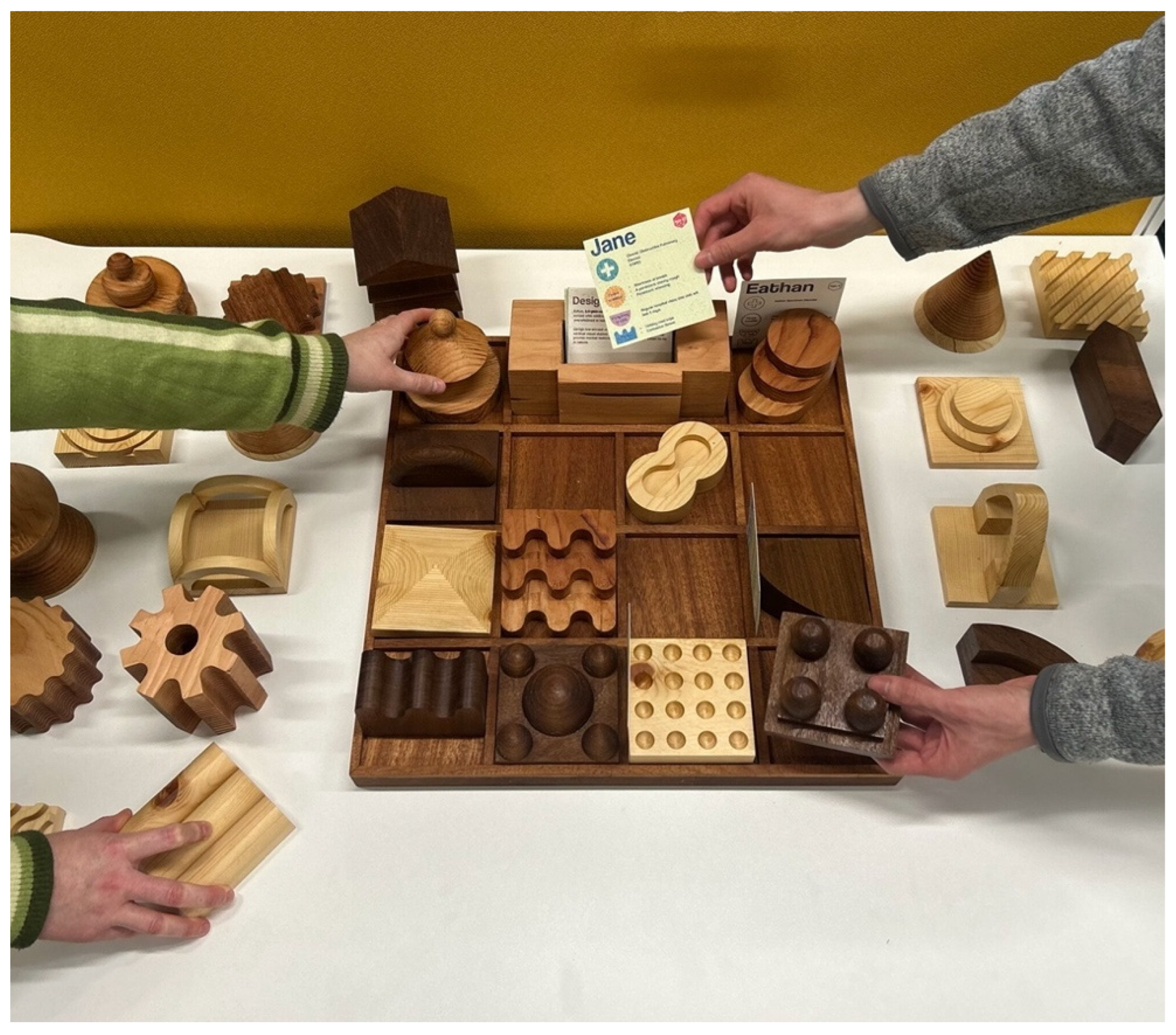

Mosaic Landscapes is a board game (

Figure 12) that engages communities in designing inclusive healthcare gardens to enhance health and wellbeing. The interactive game is designed to facilitate discussions around NHS Scotland land use. Users can design their own hospital gardens, contribute new personas, or suggest game pieces to improve the game. By encouraging a holistic approach to healthcare garden planning, the game acts as a practical, educational, and facilitative tool.

The board game uses personas representing various health conditions, prompting empathy and creative problem-solving. Players work together to design gardens that address multiple needs, integrating therapeutic, social, and production spaces. By emphasising cradle-to-cradle design principles, the game creates sustainable and inclusive healthcare gardens while encouraging communities to consider the needs of others.

3.6. Theme 6, Sustainable Digital Design

This theme explores how data analytics and scenario-led interactions can drive the redesign of health and social care services, evaluate their impact on resource expenditure, and influence behaviours for more sustainable healthcare delivery. A key research question underpinning this project is:

How can design research in ‘serious games’ inform approaches to resource management?

Flow is a serious game that integrates design, healthcare, education, and climate strategy at the intersection of games design, HCI, health innovation, and sustainability. Developed in collaboration with NHS Tayside, Flow simulates day to day emergency care use, as well as climate scenarios, to support improved public decision-making. It directly addresses NHS Scotland’s threefold priorities:

Reducing Emergency Department (ED) delays.

Supporting environmental sustainability by encouraging more informed, guideline-based healthcare decisions.

Faster access for patients with urgent needs.

Using real-world data, such as anonymised patient journeys, unscheduled care statistics, and NHS Inform guidance, Flow helps visualise urgent and semi-urgent care demand across NHS Tayside emergency departments. The game educates users on the most appropriate service options, aiming to reduce unnecessary travel, wait times, and resource use (

Figure 13). The Flow game environment also incorporates patterns in admissions, care pathways, and condition-specific impacts on service delivery. NHS clinical guidance, clinician-recommended actions, and weather data from the UK Met Office. Together, these data enable the simulation of realistic healthcare scenarios to support public understanding and informed decision-making.

Our approach combines design thinking and game design methods, including:

Empathy mapping and ideation

Iterative development of patient personas and hospital journeys

Collaboration with NHS Scotland to develop a data ecosystem map, visualising key data flows and supply chain dependencies

Participatory Scenario Building

Through a structured participatory approach and a custom micro-scenario tool (

Figure 14), design researchers and healthcare professionals have co-created climate-related stress scenarios. These challenge players to interpret threats such as heatwaves and their health impacts, simulate healthcare responses and support improved understanding of how climate pressures can contribute to inefficiencies and breakdowns in healthcare systems. This foundation enables robust data modelling to represent NHS Scotland’s current healthcare system. Through simulated “playable episodes,”

Flow recreates real decision points and environmental challenges, helping test potential interventions in a safe, educational setting.

3.7. Theme 7, Sustainable Exploratory Projects

This theme explores innovative ways to showcase green transition initiatives, proposing new approaches to healthcare leadership, staff training, and sustainability-driven design to achieve Net Zero targets. A major question in this theme is how can exploratory projects point the way towards a regenerative framework for design in healthcare settings?

Medi-Flax is an innovative project focused on creating a sustainable textile economy for healthcare by utilising local natural fibres.

Medi-Flax is an ambitious project aiming to assess whether a local soil-to-soil natural fibre textile economy, specifically the production of bast fibre such as flax, could provide linen textiles useful for healthcare (

Figure 15). Today, textiles made from petrochemical-derived fibres and dyes or from water-intensive cotton are extensively used in hospitals.

We are developing a suite of open-source machinery for farm-scale textile processing, which includes building, testing, prototyping, and sharing these designs in an open way. This approach ensures that the designs are available for modification and redistribution. Ultimately, this project connects regenerative agriculture to garment production, enabling the bio-regional production of natural fibre yarn. Together with our collaborators across the country, we aim to build a soil-to-soil textile economy in the UK.

4. Materials and Methods

This section details the overall methodology adopted by the Design HOPES project. It reflects on the common tools and methods used across the various projects outlined above, and their resulting impacts towards a sustainable health and social care ecosystem. The Design HOPES project tackles a complex, multifarious problem, and the team itself consists of a significant number and range of participants including researchers from a variety of design disciplines such as product, architecture, and textile design, researchers from computing, business, and health and life sciences as well as health and social care partners from NHS Scotland, the third and voluntary sector, and organisations in the design economy sector. Building cohesion in this context is challenging, and to address this issue, the project was structured around a series of four Design Sprints where the collective research team, project partners and invited guests could come together.

Central to Design HOPES is its co-design approach, with the voice of NHS Scotland staff core to the definition of problems and the generation of appropriate design-led interventions. By incorporating NHS Scotland staff and other relevant stakeholders at Design Sprints, and in the design research activities of each theme, some clear characteristics emerged. Firstly, time and resource pressures were a primary concern and a barrier to change. Health and social care services are increasingly required to do more with less [

25], meaning that although staff would like to transition towards more effective working methods, they lack the capacity to develop and implement new models. Another major challenge is the interaction of a wide range of stakeholders with complex dynamics. The NHS is the largest employer in Scotland with nearly 200,000 people and is a deeply hierarchical organisation with distinctly defined job roles. This, combined with the fact that it serves the breadth of the national population (not only patients but supporting families and visitors) means that there are a huge number of competing incentives and agendas in delivery of its overall goals that are not easily tracked by performance management systems [

26]. Nevertheless, there remains strong incentives towards health and wellbeing amongst staff. Individuals who work in healthcare have a tendency towards high levels of empathy and are motivated to help individuals [

27]. While this is a powerful force to be harnessed, it can lead to high levels of stress and disillusionment when it is not possible to deliver the services expected [

28,

29]. There is also a historical and ongoing conflict between regulations and desire for change. The stiff regulatory environment to protect hygiene and safety, and the bureaucratic culture that has emerged in the wake of this, means that change can be difficult to implement even where opportunities and benefits are clear [

30].

The conversations that emerged through the Design Sprints have helped to embed the overall project ethos, and facilitated the development of connections between NHS Scotland staff and project partners with specific themes. The design-led methods and tools that were subsequently co-created, and are outlined above, have helped deliver a range of benefits that are focussed on increased adoption of circular, sustainable innovative design solutions (i.e., products, services, strategies and policies) and health system transformations. The projects spread across the seven themes (

Table 1) will generate social, cultural environmental and economic impact assessed using a quadruple bottom line framework developed in earlier research [

31].

5. Results

NHS staff often find it difficult to engage in research activities, with time constraints and competing priorities around patient-centred care being repeatedly cited as significant barriers [

32]. To engage NHS Scotland staff in flexible and accessible ways, Design HOPES’ projects such as the

Green Ward Toolkit,

Rhythms and Rhymes, and the

Mosaic Landscape projects deployed “Pop-Up” installations in the exploratory stages to facilitate conversations and capture valuable insights into NHS Scotland staff’s current understanding of Net Zero and sustainable practices. Results showed that despite strong motivations for more sustainable healthcare, knowledge remains limited, especially in a complex system with competing priorities. While challenges were identified in pharmacy processes, medication management and equipment reuse, a range of innovative ideas also emerged, including visualising waste management, addressing upskilling and training needs, and empowering NHS Scotland staff to drive behavioural change. Further into the GWT project, an interactive research station was positioned outside a hospital ward to collect data from staff to inform the development of themes and actions for the toolkit. To maintain high levels of engagement, the interactive research station offered flexible and accessible activities to fit with NHS Scotland staff’s dules and support self-paced learning. For instance, a priority matrix was used to categorise levels of knowledge and importance around the themes of waste, proactive care, travel, energy, water and prescribing. It is important to note that these creative and novel approaches to data collection encouraged NHS Scotland staff to provide deeper insights and more nuanced responses about their everyday working practices and environments.

Design HOPES’ projects including

Flow,

Rhythms and Rhymes, and

Medi-Flax strengthens critical design thinking in healthcare by demonstrating how design-led interventions can help NHS Scotland partners navigate the complex systemic challenges that they face. Responding to Loewe’s [

33] call to support designers and collaborators in addressing social, political, and technological contradictions, these projects demonstrate how design can be employed not only to address surface problems, but to explore and tackle the deeper causes of stress and inefficiency in wider health service contexts. By building participatory maps of how data and care decisions are represented across services, and by using playable micro-scenarios to test how climate-related events affect healthcare services, projects such as

Flow helps NHS Scotland staff, researchers and the general public, to think systemically and plan ahead. This goes beyond what Loewe criticises as a simplified version of design thinking that avoids difficult issues, instead showing how design can be used for reflection, collaboration, and practical change. This approach aligns with Dunne and Raby’s [

3] idea of critical design as a means to question established assumptions and imagine preferred futures. Design HOPES’ projects such as

Flow do this by building real healthcare data into playable episodes that help participants rethink how care is delivered, correlate climate change and health implications, and envisage how the system might adapt under future pressures. In doing so, the project uses design, both as an analytical tool for understanding complex systems and as a transformative design-led intervention capable of fostering more sustainable and equitable healthcare futures.

6. Discussion

In our ongoing Design HOPES’ research, we have empowered design-led research for net zero challenges in innovative and collaborative ways. Design HOPES’ work with NHS Scotland, industry partners, and other relevant stakeholders has utilised a range of innovative co-design and co-production methods and tools to develop around 20 designed prototypes including new products, services, and systems. In a review of design studies literature, Hernandez et al. [

34] highlight the multifarious roles design can play in innovation (e.g., to differentiate from competitors, to facilitate adoption, to translate ideas into concepts). Two overarching functions that encompass the entirety of the design process include design as:

- (1)

An articulator and integrator of concepts, people, and functions;

- (2)

Design as a creative, generative thinking process.

Considering design firstly as an articulator and integrator, Design HOPES’ researchers have been collaborating closely with key clinical and operational figures across NHS Scotland health boards, building trust through four intensive design sprints and sustained specific thematic projects. Doing so over a period of time has been fundamental in creating a setting where ideas can be shared freely. With this foundational trust established, various design-led research tools have provided a variety of means to closely observe, interrogate and understand user (NHS Scotland staff) behaviour in order to respond to contextual needs.

This is particularly important where values and beliefs are not easily articulated or motivations for behaviours not readily apparent [

35]. Across the seven Design HOPES’ themes we have seen design-led tools such as pop-up exhibitions, interactive games, cultural probes and future scenarios being deployed to help bring clarity to the specific requirements of NHS Scotland groups and individuals. As a precursor to these collaborations, we have at a project level worked to secure appropriate ethics approval for NHS Scotland engagement in general design collaboration, and at a theme level to secure specific approval for discrete activities of deeper engagement. In addition to the legal and ethical necessity of this, it has been an important activity in highlighting procedural and cultural issues associated with the organisations involved. The necessity to, for example, focus on staff rather than patient engagement has dictated the format and configuration of the design tools employed.

Secondly, the act of design is a creative, playful and engaging process, and when delivered effectively can allow designers and non-designers to collaborate fruitfully in the generation of new solutions that are innovative but grounded by expertise in the relevant context [

36]. Most of us find creative involvement to be rewarding [

37], and co-design activities, with designers acting as facilitators, have mobilised and motivated clinicians including surgeons, anaesthetists, and nurses, care-givers, technicians, administrators and other relevant stakeholders to generate new perspectives on existing problems. Across the Design HOPES’ themes, we have created design-led methods and tools to meet the demands of the healthcare workforce, e.g., online formats for remote contribution, timings to accommodate shift working, acknowledgement of regulatory and procedural constraints. Where scepticism has arisen, and individuals have been reluctant or unwilling to engage, we have found the provision of visual material and tangible prototypical artefacts critical in stimulating engagement. We have made extensive use of quick-and-dirty and low fidelity models and prototypes that make design possibilities tangible and aid effective communication for those both directly involved in, and those observing, the design process. This principle applies from projects ranging from greenspace configuration to apparel design, and has allowed the team to iteratively design, make, test and evolve solutions in conjunction with NHS Scotland staff and to highlight the possibilities to NHS Scotland and Scottish Government policy makers.

Together, these functions embody how design has been utilised to help all types of healthcare professionals, from frontline medical staff to supporting managers, recognise where issues lie, imagine new ways of working, and participate in their design and implementation.