Improving Work–Life Balance in Academia After COVID-19 Using Inclusive Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

- By analyzing spillover between roles [9];

- Through border theory, where individuals are border-crossers between work and family spheres, influenced by border-keepers like spouses and supervisors [10];

- Through person–environment fit theory, considering alignment between an individual’s various life roles, aiming for minimal conflict and balanced engagement and satisfaction across all domains [11].

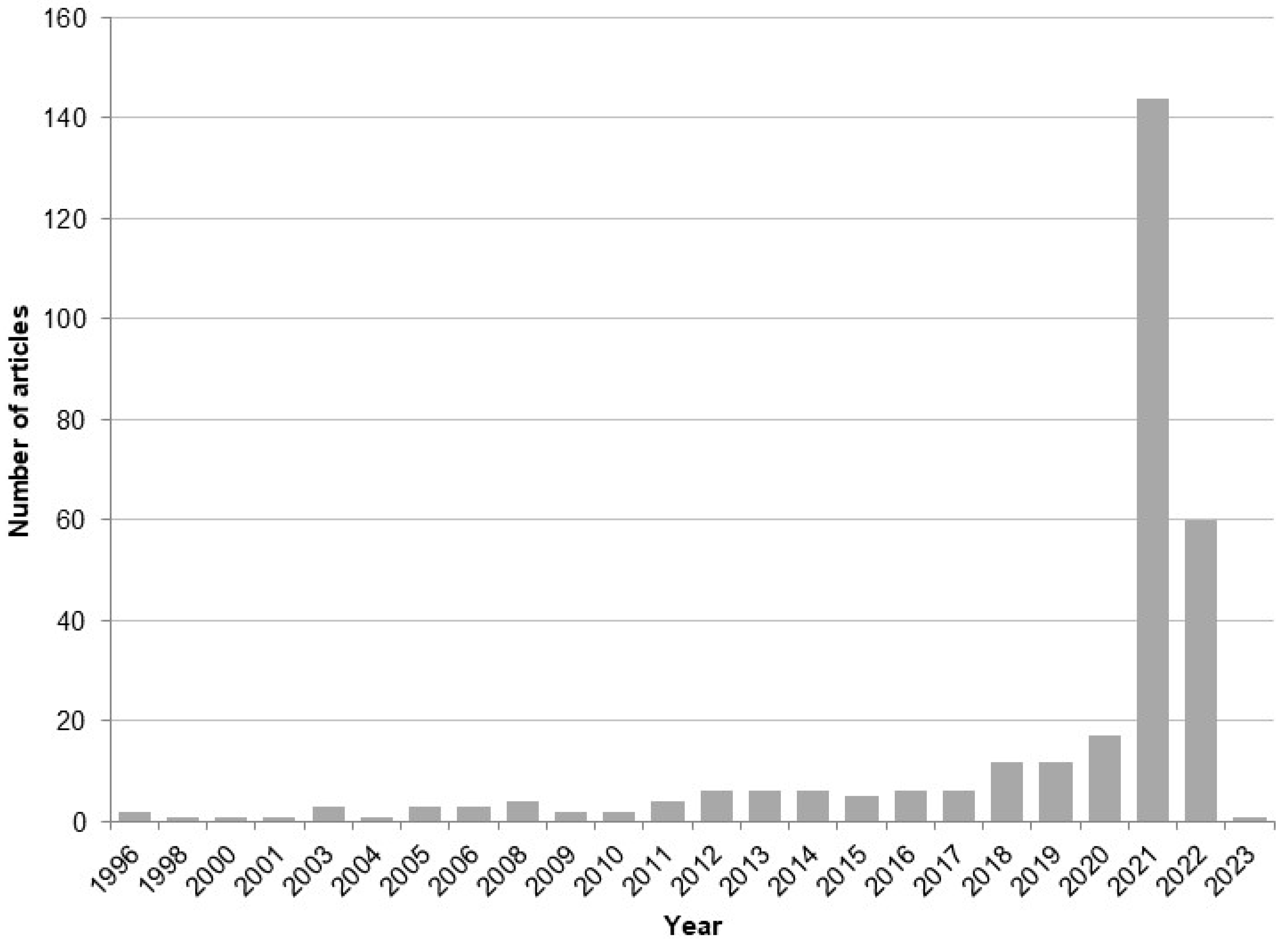

2. Materials and Methods

- Providing an intersectional understanding of WLB, highlighting how different academic populations experience these challenges in distinct ways.

- Positioning COVID-19 as a driver for structural reform, rather than an anomaly from which academia must bounce back.

- Bridging WLB research and inclusive policy design, with a focus on actionable recommendations for institutions and policymakers.

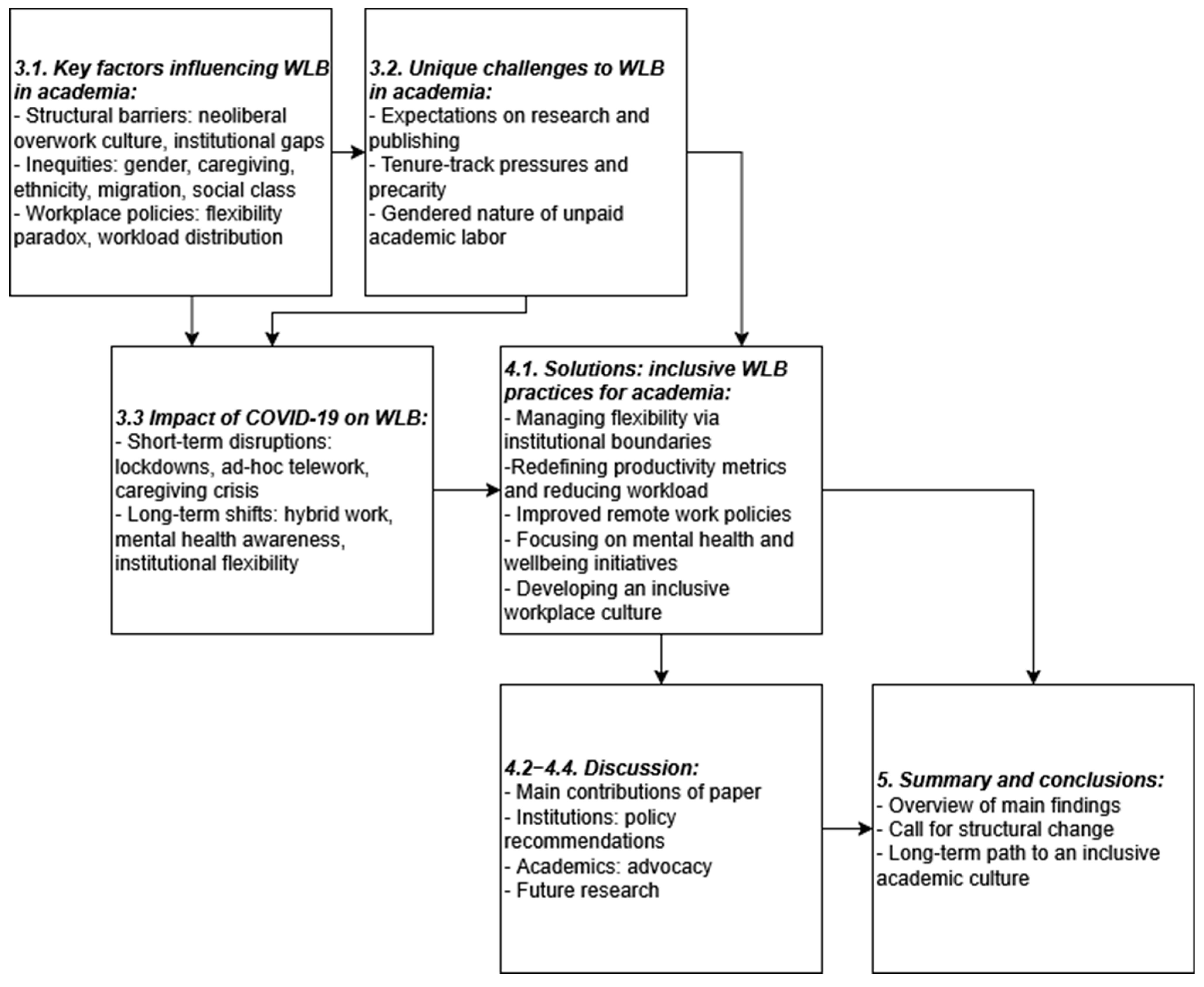

3. Results

3.1. Key Factors Impacting Work–Life Balance in Academia

3.1.1. Theoretical Basis of Work–Life Balance Research

3.1.2. Structural Barriers: Neoliberal Overwork Culture and Institutional Gaps

3.1.3. Inequities

Gender

Parenting

Ethnicity

Migration Status

Social Class

Other Aspects and Intersectionality

3.1.4. Workplace Policies: The Flexibility Paradox, Workload Distribution

3.2. Unique Challenges to Work–Life Balance in Academia

- Expectations on research and publishing;

- Tenure-track pressures and precariousness;

- The gendered nature of unpaid academic labor.

3.3. Impact of COVID-19 on Work–Life Balance

3.3.1. Short-Term Disruptions: Lockdowns, Ad Hoc Telework, Burnout

3.3.2. Long-Term Shifts: Hybrid Work, Mental Health Awareness, Institutional Flexibility

4. Discussion

4.1. Solutions: Inclusive Practices for Work–Life Balance

- Set institutional boundaries to flexibility, including equitable hybrid work setups;

- Redefine productivity metrics and reduce faculty workload;

- Use new frameworks for WLB;

- Strengthen well-being and mental health in the campus community to move to a culture of care.

4.2. Main Contributions

4.3. Actionable Takeaways

4.4. Future Work

5. Conclusions

- Work–life balance has no single definition, measurement, or theory, which makes discussing the topic complicated.

- The flexibility of academic work is experienced as a paradox: in theory, academics can work flexibly, but in reality, this flexibility often leads to erosion of boundaries and overwork, reducing WLB.

- The key factors that impact WLB in academia are structural barriers (the neoliberal culture of overwork and lack of institutional support), intersectional inequities, and workplace policies (unclear expectations around flexibility, workload distribution).

- Particular challenges for academics are the precariousness of contracts until tenure is achieved, the gendered division of labor in departments, and mental health and burnout concerns that are under-addressed at the institutional level.

- COVID-19 impacted WLB in academia directly during the lockdown due to ad hoc telework and increased caregiving and, in the longer term, due to changes in the way we work, the increased awareness of mental health, and push for institutional flexibility.

- The impact of COVID-19 on WLB in academia requires a view on the minorities: there is a disproportionate burden on women, early-career faculty, caregivers, and underrepresented minorities.

- Recommendations for inclusive WLB practices for universities include institutional boundary-setting through workload analysis and setting clear expectations, redefining productivity metrics, flexible and equitable hybrid work policies that acknowledge diverse needs, and strengthening well-being and mental health initiatives.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dilmaghani, M.; Tabvuma, V. The gender gap in work–life balance satisfaction across occupations. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 34, 398–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiden, A.; Räisänen, C.; Caven, V. Juggling work, family… and life in academia: The case of the “new” man. In Proceedings of the Association of Researchers in Construction Management, ARCOM 2012—Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference, Edinburgh, UK, 3–5 September 2012; pp. 273–283. [Google Scholar]

- Beigi, M.; Shirmohammadi, M.; Kim, S. Living the academic life: A model for work-family conflict. Work 2016, 53, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, F.T.; Meier, L.L.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann, M.A.; Ziomek-Daigle, J.; Dockery, D.J. Motherhood and counselor education: Experiences with work-life balance. Adultspan J. 2014, 13, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, G.; Jones, F. A life beyond work? job demands, work-life balance, and wellbeing in UK Academics. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2008, 17, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, J.; Boyd, E.M.; Sinha, R.; Westring, A.F.; Ryan, A.M. From “work–family” to “work–life”: Broadening our conceptualization and measurement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 82, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Collins, K.M.; Shaw, J.D. The relation between work–family balance and quality of life. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, L.K.H.; Hui, R.T.Y.; Yau, W.C.W. Work-life balance of Chinese knowledge workers under flextime arrangement: The relationship of work-life balance supportive culture and work-life spillover. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallee, M.W.; Lewis, D.V. Hyper-separation as a tool for work/life balance: Commuting in academia. J. Public Aff. Educ. 2020, 26, 484–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Caudle, D.J. Balancing academia and family life: The gendered strains and struggles between the UK and China compared. Gend. Manag. 2020, 35, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.P.; Chan, A.H.S. Exploration of the socioecological determinants of hong kong workers’ work-life balance: A grounded theory model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothbard, N.P.; Beetz, A.M.; Harari, D. Balancing the Scales: A Configurational Approach to Work-Life Balance. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2021, 8, 73–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazovich, J.L.; Smith, K.T.; Murphy Smith, L. Mother-friendly companies, work-life balance, and emotional well-being: Is there a relationship to financial performance and risk level? Int. J. Work Organ. Emot. 2018, 9, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köse, S.; Baykal, B.; Bayat, İ.K. Mediator role of resilience in the relationship between social support and work life balance. Aust. J. Psychol. 2021, 73, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasingam, S.; Lee, S.T.; Mohd Zain, K.N. Demystifying the life domain in work-life balance: A Malaysian perspective. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieu, V. Relationship between Work-Life Balance, Religiosity and Employee Engagement: A Proposed Moderated Mediation Model. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmaghani, M. Deep-Level Religious Diversity and Work-Life Balance Satisfaction in Canada. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 315–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwiech, P. Implementation of work-life balance in companies—The case of poland. IBIMA Bus. Rev. 2021, 2021, 811071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevičienė, A.; Tamaševičius, V.; Diskienė, D.; Grakauskas, Ž.; Rudinskaja, L. The mediating effect of work-life balance on the relationship between work culture and employee well-being. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2021, 22, 988–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joecks, J. The provision of work–life balance practices across welfare states and industries and their impact on extraordinary turnover. Soc. Policy Adm. 2021, 55, 1325–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, E.; Anderzén, I.; Andersén, Å.; Lindberg, P. Work-life balance predicted work ability two years later: A cohort study of employees in the Swedish energy and water sector. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T.; Jawaad, M.; Butt, I. The influence of person–job fit, work–life balance, and work conditions on organizational commitment: Investigating the mediation of job satisfaction in the private sector of the emerging market. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, E.W. Work-Life Balance: It’s All About Relationships. J. Healthc. Manag. Am. Coll. Healthc. Exec. 2021, 66, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Islam, D.M.T. Work-life Balance and Organizational Commitment: A Study of Field Level Administration in Bangladesh. Int. J. Public Adm. 2021, 44, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Ahn, H. Organizational responses to work-life balance issues: The adoption and use of family-friendly policies in Korean organizations. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2021, 26, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.; Lai, A.T.S.; Meng, X.; Lee, F.C.H.; Chan, A.H.S. Work–Life Balance of Secondary Schools Teachers in Hong Kong. Lect. Notes Netw. Syst. 2021, 219 LNNS, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.P.; Lee, F.C.H.; Teh, P.L.; Chan, A.H.S. The interplay of socioecological determinants of work–life balance, subjective wellbeing and employee wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karani, A.; Deshpande, R.; Jayswal, M.; Panda, R. Work-life balance and psychological distress: A structural equation modeling approach. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2022, 41, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, I.; Johnson, K.; Kozimor-King, M.L. Work–life balance in media newsrooms. Journalism 2021, 22, 2001–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, R. A ‘Dark Side’ of Humane Entrepreneurship? Unveiling the Side Effects of Humane Entrepreneurship on Work–Life Balance. J. Entrep. 2022, 31, 121–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riforgiate, S.E.; Kramer, M.W. The nonprofit assimilation process and work-life balance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitney, W.A. Work-Life Balance Research in Athletic Training: Perspectives on Future Directions. J. Athl. Train. 2022, 57, 207–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oskarsson, E.; Österberg, J.; Nilsson, J. Work-life balance among newly employed officers—A qualitative study. Health Psychol. Rep. 2021, 9, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santhanam, N.; Ramesh Kumar, J.; Kumar, V.; Saha, R. Employee turnover intention in the milieu of human resource management practices: Moderating role of work-life balance. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2021, 24, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.H. Improving Work–Life Balance for Female Civil Servants in Law Enforcement: An Exploratory Analysis of the Federal Employee Paid Leave Act. Public Pers. Manag. 2022, 51, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.S.; Lee, E.J.; Na, T.K. The Mediating Effects of Work–Life Balance (WLB) and Ease of Using WLB Programs in the Relationship between WLB Organizational Culture and Turnover Intention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyani, S.; Salameh, A.A.; Komariah, A.; Timoshin, A.; Hashim, N.A.A.N.; Fauziah, R.S.P.; Mulyaningsih, M.; Ahmad, I.; Ul din, S.M. Emotional Regulation as a Remedy for Teacher Burnout in Special Schools: Evaluating School Climate, Teacher’s Work-Life Balance and Children Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 655850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulaziz, A.; Bashir, M.; Alfalih, A.A. The impact of work-life balance and work overload on teacher’s organizational commitment: Do Job Engagement and Perceived Organizational support matter. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 9641–9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, O.; Atkinson, R.; Noury, L.; Ruotsalainen, R. Work-life balance policies in high performance organisations: A comparative interview study with millennials in Dutch consultancies. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 35, 6–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M.; Harris, C. A moderated mediation study of high performance work systems and insomnia on New Zealand employees: Job burnout mediating and work-life balance moderating. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 34, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.; Stein, S.L. Work-life balance: History, costs, and budgeting for balance. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2014, 27, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhingra, V.; Dhingra, M. Who doesn’t want to be happy? Measuring the impact of factors influencing work–life balance on subjective happiness of doctors. Ethics Med. Public Health 2021, 16, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, E.T.; Cianfichi, L.J.; Guzman, E.; Kerr, P.M.; Krumm, J.; Hofmann, L.V.; Kothary, N. Reimagining the IR Workflow for a Better Work–Life Balance. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2021, 32, 1488–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frintner, M.P.; Kaelber, D.C.; Kirkendall, E.S.; Lourie, E.M.; Somberg, C.A.; Lehmann, C.U. The Effect of Electronic Health Record Burden on Pediatricians’ Work-Life Balance and Career Satisfaction. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2021, 12, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castles, A.V.; Burgess, S.; Robledo, K.; Beale, A.L.; Biswas, S.; Segan, L.; Gutman, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Leet, A.; Zaman, S. Work-life balance: A comparison of women in cardiology and other specialties. Open Heart 2021, 8, e001678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Gao, J.; Zhu, M.; Jin, S. Women’s Work-Life Balance in Hospitality: Examining Its Impact on Organizational Commitment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 625550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussenoeder, F.S.; Bodendieck, E.; Jung, F.; Conrad, I.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Comparing burnout and work-life balance among specialists in internal medicine: The role of inpatient vs. outpatient workplace. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2021, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussenoeder, F.S.; Bodendieck, E.; Conrad, I.; Jung, F.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Burnout and work-life balance among physicians: The role of migration background. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2021, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Maxwell-Jones, R.; Edwards, A.M.; Knutton, N. Burnout in professional psychotherapists: Relationships with self-compassion, work–life balance, and telepressure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, F.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.L. Gender Differences in Job Satisfaction and Work-Life Balance Among Chinese Physicians in Tertiary Public Hospitals. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 635260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J.M.; Najarian, M.M.; Ties, J.S.; Borgert, A.J.; Kallies, K.J.; Jarman, B.T. Career Satisfaction, Gender Bias, and Work-Life Balance: A Contemporary Assessment of General Surgeons. J. Surg. Educ. 2021, 78, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.G. A study on work intensity, work-life balance, and burnout among korean neurosurgeons after the enactment of the special act on korean medical residents. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2021, 64, 644–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, M.; Suzuki, E.; Takayama, Y.; Shibata, S.; Sato, K. Influence of Striving for Work–Life Balance and Sense of Coherence on Intention to Leave Among Nurses: A 6-Month Prospective Survey. Inq. J. Health Care Organ. Provision Financ. 2021, 58, 00469580211005192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, J.; Koga, M.; Nagashima, N.; Kuroda, H. The actual–ideal gap in work–life balance and quality of life among acute care ward nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.H.; Tsai, H.Y. A study of job insecurity and life satisfaction in COVID-19: The multilevel moderating effect of perceived control and work–life balance programs. J. Men’s Health 2022, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Lee, Y.C.; Huang, C.H.; Wu, C.F.; Hsueh, H.W.; Wu, H.H. A Longitudinal Study of Nurses’ Work-Life Balance: A Case of a Regional Teaching Hospital in Taiwan. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2022, 17, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribben, L.; Semple, C.J. Prevalence and predictors of burnout and work-life balance within the haematology cancer nursing workforce. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 52, 101973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribben, L.; Semple, C.J. Factors contributing to burnout and work-life balance in adult oncology nursing: An integrative review. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 50, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, K.M.; Larouche, R. Active commuting to work or school: Associations with subjective well-being and work-life balance. J. Transp. Health 2021, 22, 101118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero, I.; Epifanio, I. A data science analysis of academic staff workload profiles in spanish universities: Gender gap laid bare. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannizzo, F.; Mauri, C.; Osbaldiston, N. Moral barriers between work/life balance policy and practice in academia. J. Cult. Econ. 2019, 12, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, S.E.; Burns, A. Women Negotiating Life in the Academy: A Canadian Perspective; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–201. [Google Scholar]

- Gewinner, I. Work–life balance for native and migrant scholars in German academia: Meanings and practices. Equal. Divers. Incl. 2019, 39, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebar, R.W. “Work–life balance” in medicine: Has it resulted in better patient care? Fertil. Steril. 2021, 116, 1466–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picton, A. Work-life balance in medical students: Self-care in a culture of self-sacrifice. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprung, J.M.; Rogers, A. Work-life balance as a predictor of college student anxiety and depression. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 69, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wayne, J.H.; Musisca, N.; Fleeson, W. Considering the role of personality in the work–family experience: Relationships of the big five to work–family conflict and facilitation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 108–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, V.; Hogan, M.; Hodgins, M.; Kinman, G.; Bunting, B. An examination of gender differences in the impact of individual and organisational factors on work hours, work-life conflict and psychological strain in academics. Ir. J. Psychol. 2014, 35, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiden, M.; Widar, L.; Wiitavaara, B.; Boman, E. Telework in academia: Associations with health and well-being among staff. High. Educ. 2020, 81, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.; Boles, J.; McMurrian, R. Development and Validation of Work-Family and Family-Work Conflict Scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.; Laar, D.; Easton, S.; Kinman, G. The Work-Related Quality of Life Scale for Higher Education Employees. Qual. High. Educ. 2009, 15, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasamar, S.; Johnston, K.; Tanwar, J. Anticipation of work–life conflict in higher education. Empl. Relat. 2020, 42, 777–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E.; Johnson, A. Balancing life and work by unbending gender: Early American women psychologists’ struggles and contributions. J. Hist. Behav. Sci. 2017, 53, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krenn, M. From scientific management to homemaking: Lillian M. Gilbreth’s contributions to the development of management thought. Manag. Organ. Hist. 2011, 6, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuarrie, F.A.E. The struggle over worker leisure: An analysis of the history of the workers’ sports association in Canada. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2010, 27, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, M.; Power, N. Work-life balance as a personal responsibility: The impact on strategies for coping with interrole conflict. J. Occup. Sci. 2021, 30, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, L.S.; Picinin, C.T.; Pilatti, L.A.; Franco, A.C. Work-life balance in Higher Education: A systematic review of the impact on the well-being of teachers. Ensaio 2021, 29, 691–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindfelt, T.; Ip, E.J.; Gomez, A.; Barnett, M.J. The impact of work-life balance on intention to stay in academia: Results from a national survey of pharmacy faculty. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2018, 14, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, B.B.; Miskioglu, E.; Christou, E.; Tymvios, N. Pre and post tenure: Perceptions of requirements and impediments for mechanical engineering and mechanical engineering technology faculty. In Proceedings of the ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference Proceedings, Montréal, QC, Canada, 20–24 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Popoola, S.O.; Fagbola, O.O. Work-Life Balance, Self-Esteem, Work Motivation, and Organizational Commitment of Library Personnel in Federal Universities in Southern Nigeria. Int. Inf. Libr. Rev. 2021, 53, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denson, N.; Szelényi, K. Faculty perceptions of work-life balance: The role of marital/relationship and family status. High. Educ. 2022, 83, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwa, M.A.C. Work-life balance for sustainable development in malaysian higher education institutions: Fad or fact? Kaji. Malays. 2020, 38, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennett, R. The Corrosion of Character: The Personal Consequences of Work in the New Capitalism; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cannizzo, F. Tactical evaluations: Everyday neoliberalism in academia. J. Sociol. 2018, 54, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylijoki, O.H. Boundary-work between work and life in the high-speed university. Stud. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R. Network time and the new knowledge epoch. Time Soc. 2003, 12, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois-Shaik, F.; Fusulier, B. Understanding gender inequality and the role of the work/family interface in contemporary academia: An introduction. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 16, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.; Manzi, M.; Ojeda, D. Lives in the making power, academia and the everyday. ACME 2014, 13, 328–351. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, A. The Spaces of Graduate Student Labor: The Times for a New Union. Antipode 2000, 32, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, J. A critique of approaches to ‘domestic work’: Women, work and the pre-industrial economy. Past Present 2019, 243, 35–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffoletti, K.; Starr, K. Women Academics and Work–Life Balance: Gendered Discourses of Work and Care. Gend. Work Organ. 2016, 23, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, F.; Sciotto, G. Gender differences in the relationship between work–life balance, career opportunities and general health perception. Sustainability 2022, 14, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamolla, L.; Folguera-I-Bellmunt, C.; Fernández-I-Marín, X. Working-time preferences among women: Challenging assumptions on underemployment, work centrality and work–life balance. Int. Labour Rev. 2021, 160, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, H. The association between job quality profiles and work-life balance among female employees in korea: A latent profile analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evandrou, M.; Glaser, K. Combining work and family life: The pension penalty of caring. Ageing Soc. 2003, 23, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Brieger, S.A. When Discrimination is Worse, Autonomy is Key: How Women Entrepreneurs Leverage Job Autonomy Resources to Find Work–Life Balance. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 177, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, M.; Muhr, S.L.; Beauregard, T.A. Theorising work–life balance endeavours as a gendered project of the self: The case of senior executives in Denmark. Hum. Relat. 2022, 76, 629–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, O.; Omar, M.Z.; Rasul, M.S. The Impact of Psychological Well-Being, Employability and Work-Life Balance on Organizational Mobility of Women Engineering Technology Graduate. J. Pengur. 2021, 63, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibegbulam, I.J.; Ejikeme, A.N. Perception of work-life balance among married female librarians in university libraries in south-east Nigeria. Coll. Res. Libr. 2021, 82, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, S.; Swaminathan, L.; George, S. Impact of Work-Life Balance on Job Performance—Analysis of the Mediating Role of Mental Well-Being and Work Engagement on Women Employees in IT Sector. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Application, DASA 2021, Sakheer, Bahrain, 7–8 December 2021; pp. 204–209. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, C.; Kvs, R.R.; Dutta, P. Support Vector Machine based prediction of Work Life Balance among Women in Information Technology Organizations. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2022, 50, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, D.M. Work life balance among female school teachers [k-12] delivering online curriculum in Noida [India] during COVID: Empirical study. Manag. Educ. 2021, 37, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurup, A.; Raj, A. Changing Patterns of Work–Life Balance of Women Scientists and Engineers in India. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2022, 27, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M. Addressing work-life balance challenges of working women during COVID-19 in Bangladesh. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 71, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Ali, K.B.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, A. Supervisory and co-worker support on the work-life balance of working women in the banking sector: A developing country perspective. J. Fam. Stud. 2021, 29, 306–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dousin, O.; Collins, N.; Bartram, T.; Stanton, P. The relationship between work-life balance, the need for achievement, and intention to leave: Mixed-method study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 1478–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muasya, G. Print Media Framing of Definitions and Causes of, and Solutions to, Work-Life Balance Issues in Kenya. Communicatio 2021, 47, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, E.J.; Lindfelt, T.A.; Tran, A.L.; Do, A.P.; Barnett, M.J. Differences in Career Satisfaction, Work–life Balance, and Stress by Gender in a National Survey of Pharmacy Faculty. J. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 33, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, R. The trouble with ‘work–life balance’ in neoliberal academia: A systematic and critical review. J. Gend. Stud. 2022, 31, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes-López, E.; Simbürger, E. Juggling academics in the absence of university policies to promote work-life balance: A comparative study of academic work and family in Chile and Spain. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2021, 29, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekoya, O.D.; Ajonbadi, H.A.; Okorie, G.I.; Jimoh, I.O. Beyond the call of duty: Realities of work-life balance in the united arab emirates education sector. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2021, 22, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.; Ko, H.; Chung, Y.; Woo, C. Do gender equality and work–life balance matter for innovation performance? Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 33, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudbjörg, L.; Rafnsdottir, G.; Heijstra, T. Balancing Work-family Life in Academia: The Power of Time. Gend. Work Organ. 2011, 20, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayya, S.S.; Martis, M.; Ashok, L.; Monteiro, A.D.; Mayya, S. Work-Life Balance and Gender Differences: A Study of College and University Teachers From Karnataka. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211054479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekchiri, S.; Eversole, B.A.W. Perceived work-life balance: Exploring the experiences of professional Moroccan women. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2021, 32, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biletska, I.O.; Kotlova, L.O.; Kotlovyi, S.A.; Beheza, L.Y.; Kulzhabayeva, L.S. Empirical study of family conflicts as a factor of emotional burnout of a woman. J. Intellect. Disabil.—Diagn. Treat. 2020, 8, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezu-Chukwu, U. Balancing motherhood, career, and medicine. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 715–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, Y. Education as care labor: Expanding our lens on the work-life balance problem. Curr. Sociol. 2022, 71, 1312–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale-McFall, C.; Eckart, E.; Hermann, M.; Haskins, N.; Ziomek-Daigle, J. Counselor Educator Mothers: A Quantitative Analysis of Job Satisfaction. Couns. Educ. Superv. 2018, 57, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, A.O.; Mensah, R.D.; Bartrop-Sackey, M.; Muah, P. Juggling between work, studies and motherhood: The role of social support systems for the attainment of work–life balance. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverberi, E.; Manzi, C.; Van Laar, C.; Meeussen, L. The impact of poor work-life balance and unshared home responsibilities on work-gender identity integration. Self Identity 2021, 21, 588–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa, R.; Katsura, T. Maternal work–life balance and children’s social adjustment: The mediating role of perceived stress and parenting practices. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Potočnik, K. The impact of the depletion, accumulation, and investment of personal resources on work–life balance satisfaction and job retention: A longitudinal study on working mothers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 131, 103656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, L.; Schnettler, B.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Lobos, G.; Lapo, M.; Adasme-Berríos, C.; Hueche, C. Resource Transmission is not Reciprocal: A Dyadic Analysis of Family Support, Work-Life Balance, and Life Satisfaction in Dual-Earner Parents with Adolescent Children. Sex Roles 2021, 85, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Grunert, K.G.; Lobos, G.; Lapo, M.; Hueche, C. Testing the Spillover-Crossover Model between Work-Life Balance and Satisfaction in Different Domains of Life in Dual-Earner Households. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 1475–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koon, V.Y. A multilevel analysis of work–life balance practices. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2022, 60, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, G.N.; Greenhaus, J.H.; Allen, T.D.; Johnson, R.E. Introduction to Special Topic Forum: Advancing and Expanding Work-Life Theory from Multiple Perspectives. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodelzon, K.; Shah, S.; Schweitzer, A. Supporting a Work-Life Balance for Radiology Resident Parents. Acad. Radiol. 2021, 28, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliano, K.; Ceppa, D.P.; Antonoff, M.; Donington, J.S.; Kane, L.; Lawton, J.S.; Sen, D.G. Women in Thoracic Surgery 2020 Update—Subspecialty and Work-Life Balance Analysis. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2022, 114, 1933–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafer, M.P.; Frants, A.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Lee, J.W. Gender Differences in Compensation, Mentorship, and Work-Life Balance within Facial Plastic Surgery. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, E787–E791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.; Pandey, M. A Study on Moderating Role of Family-Friendly Policies in Work–Life Balance. J. Fam. Issues 2021, 43, 2087–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, C.S.; Schmidt, M.L. Fixing the system, not the women: An innovative approach to faculty advancement. J. Women’s Health 2008, 17, 1399–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.Y. An unforeseen story of alpha-woman: Breadwinner women are more likely to quit the job in work-family conflicts. Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 6009–6021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Bristol. Women ‘Less Likely to Progress at Work’ than Their Male Counterparts Following Childbirth. Available online: https://phys.org/news/2019-10-women-male-counterparts-childbirth.html (accessed on 15 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Browne, C.V. Women’s employment, work-life balance policies, and inequality across the life course: A comparative analysis of Japan, Sweden and the United States. J. Women Aging 2022, 34, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohara, M.; Maity, B. The Impact of Work-Life Balance Policies on the Time Allocation and Fertility Preference of Japanese Women. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 2021, 60, 101134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mačernytė-Panomariovienė, I.; Krasauskas, R. A Father’s Entitlement to Paternity and Parental Leave in Lithuania: Necessary Legislative Changes following the Adoption of the Directive on Work-Life Balance. Rev. Cent. East Eur. Law 2021, 46, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanquerel, S. French Fathers in Work Organizations: Navigating Work-Life Balance Challenges. In Engaged Fatherhood for Men, Families and Gender Equality; Contributions to Management Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Moreno, A. The intersection of reproductive, work-life balance and early-education and care policies: ‘solo’ mothers by choice in the UK and Spain. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne-Manneville, S. Having it all, a scientific career and a family. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, M.A.; Wolfinger, N.H.; Goulden, M. Do Babies Matter? Gender and Family in the Ivory Tower; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Solanki, S.; Mandaviya, M. Does Gender Matter? Job Stress, Work-Life Balance, Health and Job Satisfaction among University Teachers in India. J. Int. Women’s Stud. 2021, 22, 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, M.; Fonseca, C.; Bao, J. Work and family conflict in academic science: Patterns and predictors among women and men in research universities. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2011, 41, 715–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, K.L. Challenges Facing Parents in Academia. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 936–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascom-Slack, C. Balancing Science and Family: Tidbits of Wisdom from Those Who’ve Tried It and Succeeded. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2011, 84, 219–225. [Google Scholar]

- Kachchaf, R.; Hodari, A.; Ko, L.; Ong, M. Career-Life Balance for Women of Color: Experiences in Science and Engineering Academia. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2015, 8, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, M.-P.; Robertson, M. ‘You Scratch My Back and I’ll Scratch Yours’? Support to Academics Who Are Carers in Higher Education. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomert, C.; Leinfellner, S. Images, ideals and constraints in times of neoliberal transformations: Reproduction and profession as conflicting or complementary spheres in academia? Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 16, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirick, R.G.; Wladkowski, S.P. Pregnancy, Motherhood, and Academic Career Goals:Doctoral Students’ Perspectives. Affilia 2018, 33, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, S.C. Mothers do not make good workers: The role of work/life balance policies in reinforcing gendered stereotypes. Glob. Discourse 2018, 8, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trussell, D.E. Pinstripes and Breast Pumps: Navigating the Tenure-Motherhood-Track. Leis. Sci. 2015, 37, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Laughlin, E.M.; Bischoff, L.G. Balancing Parenthood and Academia: Work/Family Stress as Influenced by Gender and Tenure Status. J. Fam. Issues 2005, 26, 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.R.; O’Brien, K.R.; Hebl, M.R. Fleeing the Ivory Tower: Gender Differences in the Turnover Experiences of Women Faculty. J. Women’s Health 2017, 26, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huppatz, K.; Sang, K.; Napier, J. ‘If you put pressure on yourself to produce then that’s your responsibility’: Mothers’ experiences of maternity leave and flexible work in the neoliberal university. Gend. Work. Organ. 2019, 26, 772–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidis, M.P. Gender-Related Work Stressors in Tertiary Education. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2008, 17, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araneda-Guirriman, C.; Garrido-Rivera, A.; Sepúlveda-Páez, G.; Peñaloza-Díaz, G. Women’s challenges in Chilean neoliberal academia: Academic workload and its impact on work-life balance. Gend. Educ. 2025, 37, 454–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, J.M.; Morrison, M.A. It’s “like walking on broken glass”: Pan-Canadian reflections on work–family conflict from psychology women faculty and graduate students. Fem. Psychol. 2018, 28, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.; Myers, B.; Ravenswood, K. Academic careers and parenting: Identity, performance and surveillance. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poronsky, C.B.; Doering, J.J.; Mkandawire-Valhmu, L.; Rice, E.I. Transition to the tenure track for nurse faculty with young children: A case study. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2012, 33, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilton, S.; Ross, L. Flexibility, Sacrifice and Insecurity: A Canadian Study Assessing the Challenges of Balancing Work and Family in Academia. J. Fem. Fam. Ther. 2017, 29, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comer, D.R.; Stites-Doe, S. Antecedents and Consequences of Faculty Women’s Academic–Parental Role Balancing. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2006, 27, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantsoght, E.O.L.; Tse Crepaldi, Y.; Tavares, S.G.; Leemans, K.; Paig-Tran, E.W.M. Challenges and Opportunities for Academic Parents During COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 645734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertlein, K.M.; Grafsky, E.L.; Owen, K.; McGillivray, K. “My Life is Too Chaotic to Practice What I Preach”: Perceived Benefits and Challenges of Being an Academic Women in Family Therapy and Family Studies Programs. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2018, 40, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendák-Kabók, K. Women’s work–life balance strategies in academia. J. Fam. Stud. 2020, 28, 1139–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, M.-P.; Kerner, C. Care in academia: An exploration of student parents’ experiences. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2015, 36, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Ruderman, M.N. Work-family flexibility and the employment relationship. In The Employee-Organization Relationship: Applications for the 21st Century; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 223–253. [Google Scholar]

- Springer, K.W.; Parker, B.K.; Leviten-Reid, C. Making Space for Graduate Student Parents:Practice and Politics. J. Fam. Issues 2009, 30, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.; Brougham, D. Work antecedents and consequences of work-life balance: A two sample study within New Zealand. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 33, 784–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyeka, W.; Maharaj, A. A quantitative study on salient work-life balance challenge(s) influencing female information and communication technology professionals in a South African telecommunications organisation. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 20, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.A.; Lehmann, M. Agents of change: Universities as development hubs. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novich, M.; Garcia-Hallett, J. Strategies for Balance: Examining How Parents of Color Navigate Work and Life in the Academy. In The Work-Family Interface: Spillover, Complications, and Challenges; Sampson Lee, B., Josip, O., Eds.; Contemporary Perspectives in Family Research; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2018; Volume 13, pp. 157–184. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, E.; Chew, I.A. Work-life balance among self-initiated expatriates in Singapore: Definitions, challenges, and resources. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 4612–4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreshidi, N.M.; Alsharari, A.F. Work-life balance of expatriate nurses working in acute care settings. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 3201–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, C.; Berger, S.; Krug, K.; Mahler, C.; Wensing, M. Internationally trained nurses and host nurses’ perceptions of safety culture, work-life-balance, burnout, and job demand during workplace integration: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maidanik, I. Understanding international migrants’ work-life balance through the prism of their working time duration: Evidence from the ukrainian case. J. Contemp. Cent. East. Eur. 2021, 29, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoshchuk, I.A.; Gewinner, I. Still a superwoman? How female academics from the former Soviet Union negotiate work-family balance abroad. Monit. Obs. Mneniya: Ekon. I Sotsial’nye Peremeny 2020, 155, 408–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, A.S.; Morris, D.; Sego, A. Navigating the Demands of Tenure-Track Positions. Health Promot. Pract. 2022, 24, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su-Russell, C.; James, A.G. Chinese international scholars’ work–life balance in the united states: Stress and strategies. J. Int. Stud. 2021, 11, 484–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Turner, M. Exploring the relationship between bodily pain and work-life balance among manual/non-managerial construction workers. Community Work Fam. 2021, 25, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, T. Work–life balance and gig work: ‘Where are we now’ and ‘where to next’ with the work–life balance agenda? J. Ind. Relat. 2021, 63, 522–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, V.J. Measuring the Change in Faculty Perceptions over Time: An Examination of Their Worklife and Satisfaction. Res. High. Educ. 2005, 46, 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J. Beyond ‘juggling’ and ‘flexibility’: Classed and gendered experiences of combining employment and motherhood. Sociol. Res. Online 2006, 11, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K.; Fagan, C.; McDowell, L.; Perrons, D.; Ray, K. Class transformation and work-life balance in urban britain: The case of manchester. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 2259–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, M.C.; Heffron, A.S.; Kwan, J.M. Characteristics, barriers, and career intentions of a national cohort of LGBTQ+ MD/PhD and DO/PhD trainees. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, M. A social partnership approach to work-life balance in the european union—The Irish experience. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2005, 20, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.; Kim, J.S.; Faerman, S.R. The influence of societal and organizational culture on the use of work-life balance programs: A comparative analysis of the United States and the Republic of Korea. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 58, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmaghani, M.; Tabvuma, V. Fragile Families in Quebec and the Rest of Canada: A Comparison of Parental Work-Life Balance Satisfaction. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2022, 41, 695–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satpathy, I.; Patnaik, B.C.M.; Palai, D. Intricacies of multi generational workforce in construction sector: Review study. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous, T.; Ali, M.; French, E. Use of flexible work practices and employee outcomes: The role of work-life balance and employee age. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 29, 833–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jammaers, E.; Williams, J. Care for the self, overcompensation and bodily crafting: The work–life balance of disabled people. Gend. Work Organ. 2021, 28, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, L.C.; Crawford, K.F. Best Practices for Normalizing Parents in the Academy: Higher- and Lower-Order Processes and Women and Parents’ Success. PS: Political Sci. Politics 2020, 53, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, W. Improving Work Life Balance through the use of Smart Work Experience. In Proceedings of the Proceedings—2021 21st ACIS International Semi-Virtual Winter Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking and Parallel/Distributed Computing, SNPD-Winter 2021, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 28–30 January 2021; pp. 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Piscopo, G.; Loia, F.; Adinolfi, P. Framing smart working in the Covid-19 era: A data driven approach. Puntoorg Int. J. 2022, 1, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotecha, K.; Ukpere, W.; Geldenhuys, M. The effect of family relationships on technology-assisted supplemental work and work-life conflict among academics. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotecha, K.; Ukpere, W.; Geldenhuys, M. Technology and work-life conflict of academics in a South African higher education institution. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senarathne Tennakoon, K.L.U. Empowerment or enslavement: The impact of technology-driven work intrusions on work–life balance. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2021, 38, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ollier-Malaterre, A.; Lu, C.Q. The impact of techno-stressors on work–life balance: The moderation of job self-efficacy and the mediation of emotional exhaustion. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 122, 106811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, A.S.; Sauf, R.A.; Devadhasan, B.D.; Meyer, N.; Vetrivel, S.C.; Magda, R. Themediating role ofperson-job fit between work-life balance (Wlb) practices and academic turnover intentions inindia’s higher educational institu-tions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10497, https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910497; Erratum in Sustainability 2022, 14, 3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny Christyanto, F.; Tricahyadinata, I.; Lestari, A.S.D. The Effect of Person-Job Fit And Work-Life Balance As Well As Job Involvement on The Performance of Employees of The Ombudsman of The Republic of Indonesia At The Representative Office. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2025, 6, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UCU. UCU Workload Survey 2016; UCU: Urdaneta City, Philippines, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lashuel, H.A. Mental health in academia: What about faculty? eLife 2020, 9, e54551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Engen, M.L.; Bleijenbergh, I.L.; Beijer, S.E. Conforming, accommodating, or resisting? How parents in academia negotiate their professional identity. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 46, 1493–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulitz, T.; Goisauf, M.; Zapusek, S. Academic way of life? On practical barriers of the work-life-balance concept in the academic field. Osterreichische Z. Soziol. 2016, 41, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanac, G.; Hartley, J. Issues of work-life balance among JASIST authors and editors. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2013, 64, 2182–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotini-Shah, P.; Man, B.; Pobee, R.; Hirshfield, L.E.; Risman, B.J.; Buhimschi, I.A.; Weinreich, H.M. Work-Life Balance and Productivity among Academic Faculty during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Latent Class Analysis. J. Women’s Health 2022, 31, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klocker, N.; Drozdzewski, D. Career progress relative to opportunity: How many papers is a baby ‘worth’? Environ. Plan. A 2012, 44, 1271–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spar, D.L. Wonder Women: Sex, Power, and the Quest for Perfection; Sarah Crichton Books: New York City, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ploszaj, A. Individual-level determinants of international academic mobility: Insights from a survey of Polish scholars. Scientometrics. 2025, 130, 2273–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribbenow, C.M.; Sheridan, J.; Winchell, J.; Benting, D.; Handelsman, J.; Carnes, M. The tenure process and extending the tenure clock: The experience of faculty at one university. High. Educ. Policy 2010, 23, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, J.; Recksiedler, C.; Linberg, A. Work from home and parenting: Examining the role of work-family conflict and gender during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Soc. Issues 2022, 79, 935–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmann, H.; Rohmann, A. Group-specific contact and sense of connectedness during the COVID-19 pandemic and its associations with psychological well-being, perceived stress, and work-life balance. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 32, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, S.; Patili, V.; Kamath, R.; Mahendra, M.; Singhal, D.K.; Bhat, V. Work-life balance amongst dental professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic -A structural equation modelling approach. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, A.; Shafaghi, M.; Adeel, A. Impact of Job Insecurity on Work–Life Balance during COVID-19 in India. Vision 2022, 29, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinberg, S.; Danielsson, P. Managers of micro-sized enterprises and COVID-19: Impact on business operations, work-life balance and well-being. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2021, 80, 1959700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayar, D.; Karaman, M.A.; Karaman, R. Work-Life Balance and Mental Health Needs of Health Professionals During COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundari, M.N.D.; Wayan Gede Supartha, I.; Made Artha Wibawa, I.; Surya, I.B.K. Does work-life balance and organizational justice affect female nurses’ performance in a pandemic era? Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2022, 20, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yayla, A.; Eskici İlgin, V. The relationship of nurses’ psychological well-being with their coronaphobia and work–life balance during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 3153–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, B.; Matushansky, J.T.; Thomas, C.; Lipner, S.R. Dermatologist work practices and work–life balance during COVID-19: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Dermatol. 2022, 61, e158–e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejero, L.M.S.; Seva, R.R.; Fadrilan-Camacho, V.F.F. Factors associated with work-life balance and productivity before and during work from home. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, A.M.D.V.; Avolio, B.; Carlier, S.I. The Relationship Between Telework, Job Performance, Work–Life Balance and Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviours in the Context of COVID-19. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirmohammadi, M.; Au, W.C.; Beigi, M. Remote work and work-life balance: Lessons learned from the covid-19 pandemic and suggestions for HRD practitioners. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2022, 25, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawanto, D.W.; Novianti, K.R.; Roz, K. Work from home: Measuring satisfaction between work–life balance and work stress during the covid-19 pandemic in indonesia. Economies 2021, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomei, M. Teleworking: A Curse or a Blessing for Gender Equality and Work-Life Balance? Intereconomics 2021, 56, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stankevičiūtė, Z.; Kunskaja, S. Strengthening of work-life balance while working remotely in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2022, 41, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuga Beršnak, J.; Humer, Ž.; Lobe, B. Characteristics of pandemic work–life balance in Slovenian military families during the lockdown: Who has paid the highest price? Curr. Sociol. 2021, 71, 866–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjálmsdóttir, A.; Bjarnadóttir, V.S. “I have turned into a foreman here at home”: Families and work–life balance in times of COVID-19 in a gender equality paradise. Gend. Work Organ. 2021, 28, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerkes, M.A.; Remery, C.; André, S.; Salin, M.; Hakovirta, M.; van Gerven, M. Unequal but balanced: Highly educated mothers’ perceptions of work–life balance during the COVID-19 lockdown in Finland and the Netherlands. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2022, 32, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonska, J.; Mietule, I.; Litavniece, L.; Arbidane, I.; Vanadzins, I.; Matisane, L.; Paegle, L. Work–Life Balance of the Employed Population During the Emergency Situation of COVID-19 in Latvia. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 682459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Kee, K.; Mao, C. Multitasking and Work-Life Balance: Explicating Multitasking When Working from Home. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2021, 65, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Mohd Yunus, W.M.A.; Badri, S.K.Z.; Panatik, S.A.; Mukhtar, F. The Unprecedented Movement Control Order (Lockdown) and Factors Associated With the Negative Emotional Symptoms, Happiness, and Work-Life Balance of Malaysian University Students During the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 566221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aczel, B.; Kovacs, M.; Van Der Lippe, T.; Szaszi, B. Researchers working from home: Benefits and challenges. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matulevicius, S.A.; Kho, K.A.; Reisch, J.; Yin, H. Academic Medicine Faculty Perceptions of Work-Life Balance before and since the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2113539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Y.; Chen, X.; Tao, S. Long commutes, work-life balance, and well-being: A mixed-methods study of Hong Kong’s new-town residents. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2025, 45, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emre, O.; De Spiegeleare, S. The role of work–life balance and autonomy in the relationship between commuting, employee commitment and well-being. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 2443–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnaweera, D.; Jayathilaka, R. In employees’ favour or not?—The impact of virtual office platform on the work-life balances. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltsa, V.-S. An empirical analysis of teleworking and its impact on work engagement. MSc Thesis, University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, Greece, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, Z.H.; Yousuf, U.; Saba, N. The implications of telecommuting on work-life balance: Effects on work engagement and work exhaustion. ResearchSquare, 11 May 2022, PREPRINT (Version 1); [CrossRef]

- Metselaar, S.A.; den Dulk, L.; Vermeeren, B. Teleworking at Different Locations Outside the Office: Consequences for Perceived Performance and the Mediating Role of Autonomy and Work-Life Balance Satisfaction. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2022, 43, 456–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Modroño, P.; López-Igual, P. Job quality and work–life balance of teleworkers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austinson, M. Teachers’ Use of Boundary Management Tactics to Maintain Work-Life Balance; Northwest Nazarene University: Nampa, ID, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ágota-Aliz, B. Flexible working practices in the ICT industry in achieving work-life balance. Stud. Univ. Babes-Bolyai Sociol. 2021, 66, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, H.; Gohar, B.; Appleby, R.; Nowrouzi-Kia, B.; Hagen, B.N.M.; Jones-Bitton, A. High Psychosocial Work Demands, Decreased Well-Being, and Perceived Well-Being Needs Within Veterinary Academia During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 746716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashencaen Crabtree, S.; Esteves, L.; Hemingway, A. A ‘new (ab)normal’?: Scrutinising the work-life balance of academics under lockdown. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensukmongkol, P.; Puyod, J.V. Influence of transformational leadership on role ambiguity and work–life balance of Filipino University employees during COVID-19: Does employee involvement matter? Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 27, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A.; Budur, T. Work–life balance and performance relations during COVID 19 outbreak: A case study among university academic staff. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2022, 15, 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erro-Garcés, A.; Urien, B.; Čyras, G.; Janušauskienė, V.M. Telework in Baltic Countries during the Pandemic: Effects on Wellbeing, Job Satisfaction, and Work-Life Balance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolor, C.W.; Nurkhin, A.; Citriadin, Y. Is working from home good for work-life balance, stress, and productivity, or does it cause problems? Humanit. Soc. Sci. Lett. 2021, 9, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprinou, V.D.I.; Tasoulis, K.; Kravariti, F. The impact of servant leadership and perceived organisational and supervisor support on job burnout and work–life balance in the era of teleworking and COVID-19. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 1071–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, E. Preface: Developing an Organization Through Work Life Balance-Driven Leave. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2021, 23, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caringal-Go, J.F.; Teng-Calleja, M.; Bertulfo, D.J.; Manaois, J.O. Work-life balance crafting during COVID-19: Exploring strategies of telecommuting employees in the Philippines. Community Work Fam. 2022, 25, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peake, L.J.; Mullings, B. Critical Reflections on Mental and Emotional Distress in the Academy. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 2016, 15, 253–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams-Hutcheson, G.; Johnston, L. Flourishing in fragile academic work spaces and learning environments: Feminist geographies of care and mentoring. Gend. Place Cult. 2019, 26, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahal, P.; Lippmann, S. Building a better work/life balance. Curr. Psychiatry 2021, 20, E1–E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S. Let’s get the work-life balance right. Br. J. Nurs. 2021, 30, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, R.; Rafiei, S.; Akbari, R.; Ebrahimi, E.H.; Dehghani, A.; Shafii, M. The relationship between work-life balance and quality of life among hospital employees. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2021, 14, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.J. Work-life balance: Choose wisely. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 37, 415–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.A. Respecting Work-Life Balance While Achieving Success. Tech. Innov. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 23, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, N.; Bollipo, S.; Repaka, A.; Sebastian, S.; Tennyson, C.; Charabaty, A. When burn-out reaches a pandemic level in gastroenterology: A call for a more sustainable work-life balance. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021, 12, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Y.; Liao, H.H.; Yeh, E.H.; Ellis, L.A.; Clay-Williams, R.; Braithwaite, J. Examining the pathways by which work-life balance influences safety culture among healthcare workers in Taiwan: Path analysis of data from a cross-sectional survey on patient safety culture among hospital staff. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e054143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S.H.; Moe, J.S.; Abramowicz, S. Work–Life Balance for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 33, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, L.S. Work-Life Balance in the Pharmaceutical Sciences: More Essential Than Ever Today. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 3649–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuzaki, T.; Iwata, N.; Ooba, S.; Takeda, S.; Inoue, M. The effect of nurses’ work–life balance on work engagement: The adjustment effect of affective commitment. Yonago Acta Medica 2021, 64, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, T.; Samanta, S.R.; Mohanty, J. Work Life Balance of Health Care Workers in the New Normal: A Review of Literature. J. Med. Chem. Sci. 2022, 5, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiber, L.; Boscher, C.; Fischer, F.; Winter, M.H.J. Work–life balance as a strategy for health promotion and employee retention: Results of a survey among human resources managers in the nursing sector. Pravent. Und Gesundheitsforderung 2021, 16, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalkow-Klincovstein, J.; Porras-Hernandez, J.D.; Villalpando, R.; Olaya-Vargas, A.; Esparza-Aguilar, M. Academic paediatric surgery and work-life balance: Insights from Mexico. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2021, 30, 151023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffeng, T.; Coffeng, P.; van Steenbergen, E. Enthusiastic in balance: Support of the work-life balance to promote performance and ambition. Tijdschr. Voor Bedr.—En Verzek. 2021, 29, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanni, A.A.; Oduaran, C.A. Person-job fit and work-life balance of female nurses with cultural competence as a mediator: Evidence from Nigeria. Front. Nurs. 2022, 9, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, D.Y.; Mujal, G.; Jin, A.; Liang, S.Y. Road to Better Work-Life Balance? Lean Redesigns and Daily Work Time among Primary Care Physicians. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 37, 2358–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.; Seman, L.O.; De Montreuil Carmona, L.J. Service innovation through transformational leadership, work-life balance, and organisational learning capability. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 33, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luturlean, B.S.; Prasetio, A.P.; Anggadwita, G.; Hanura, F. Does work-life balance mediate the relationship between HR practices and affective organisational commitment? Perspective of a telecommunication industry in Indonesia. Int. J. Learn. Intellect. Cap. 2021, 18, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, A. Identities, academic cultures, and relationship intersections: Postsecondary dance educators’ lived experiences pursuing tenure. Res. Danc. Educ. 2020, 21, 188–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddagoda, A.; Hysa, E.; Bulińska-Stangrecka, H.; Manta, O. Green work-life balance and greenwashing the construct of work-life balance: Myth and reality. Energies 2021, 14, 4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenswood, K. Greening work–life balance: Connecting work, caring and the environment. Ind. Relat. J. 2022, 53, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panojan, P.; Perera, B.A.K.S.; Dilakshan, R. Work-life balance of professional quantity surveyors engaged in the construction industry. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj Lakshmi, R.K.R.; Oinam, E. Impact of Yoga on the Work-Life Balance of Working Women During COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 785009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iremeka, F.U.; Ede, M.O.; Amaeze, F.E.; Okeke, C.I.; Ilechukwu, L.C.; Ukaigwe, P.C.; Wagbara, C.D.; Ajuzie, H.D.; Isilebo, N.C.; Ede, A.O.; et al. Improving work-life balance among administrative officers in Catholic primary schools: Assessing the effect of a Christian religious rational emotive behavior therapy. Medicine 2021, 100, e26361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogakwu, N.V.; Ede, M.O.; Amaeze, F.E.; Manafa, I.; Okeke, F.C.; Omeke, F.; Amadi, K.; Ede, A.O.; Ekesionye, N.E. Occupational health intervention for work–life balance and burnout management among teachers in rural communities. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 2923–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althammer, S.E.; Reis, D.; van der Beek, S.; Beck, L.; Michel, A. A mindfulness intervention promoting work–life balance: How segmentation preference affects changes in detachment, well-being, and work–life balance. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 94, 282–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarcona, A.; Lucas, L.; Dirhan, D. Faculty Development: Exploring Well-Being of Educators. Acad. Exch. Q. 2022, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Steketee, A.; Chen, S.; Nelson, R.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Harden, S.M. A mixed-methods study to test a tailored coaching program for health researchers to manage stress and achieve work-life balance. Transl. Behav. Med. 2022, 12, 369–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, K.P.; Griffiths, M.D.; Dsouza, D.D. Online Gaming During the COVID-19 Pandemic in India: Strategies for Work-Life Balance. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D. “I did not know what to expect”: Music as a means to achieving work-life balance. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 2021, 43, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, V.C.; Berry, G.R. Enhancing work-life balance using a resilience framework. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2021, 126, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakelants, H.; Van Droogenbroeck, F.; Chambaere, K.; Vanderstichelen, S.; De Donder, L.; Deliens, L.; De Gieter, S.; De Moortel, D.; Cohen, J.; Dury, S. A compassionate university for serious illness, death, and bereavement: Qualitative study of student and staff experiences and support needs. Death Stud. 2023, 48, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderstichelen, S.; Dury, S.; De Gieter, S.; Van Droogenbroeck, F.; De Moortel, D.; Van Hove, L.; Rodeyns, J.; Aernouts, N.; Bakelants, H.; Cohen, J.; et al. Researching Compassionate Communities From an Interdisciplinary Perspective: The Case of the Compassionate Communities Center of Expertise. Gerontologist 2022, 62, 1392–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isgro, K.; Castañeda, M. Mothers in U.S. academia: Insights from lived experiences. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2015, 53, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien Katharine, R.; Martinez Larry, R.; Ruggs Enrica, N.; Rinehart, J.; Hebl Michelle, R. Policies that make a difference: Bridging the gender equity and work-family gap in academia. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2015, 30, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiebinger, L.; Henderson, A.D.; Gilmartin, S.K. Dual-Career Academic Couples: What Universities Need to Know; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, K.; Wolf-Wendel, L. Academic Motherhood: How Faculty Manage Work and Family; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Banik, G. Strategies and techniques for new tenure-track faculty to become successful in Academia. In Proceedings of the ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference Proceedings, New Orleans, LA, USA, 26–29 June 2016. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Erren, T.C.; Mohren, J.; Shaw, D.M. Towards a good work-life balance: 10 recommendations from 10 Nobel Laureates (1996–2013). Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2021, 42, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kimmie-Dhansay, F.; Shea, J.; Amosun, S.; Swart, X.; Thabane, L. Perspectives on academic mentorship, research collaborations, career advice and work–life balance: A masterclass conversation with Professor Salim Abdool Karim. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 2022, 21, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendell, J. Deep adaptation: A map for navigating climate tragedy. Inst. Leadersh. Sustain. (IFLAS) Occas. Pap. 2019, 2, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bendell, J. Replacing Sustainable Development: Potential Frameworks for International Cooperation in an Era of Increasing Crises and Disasters. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan, L.; Bendell, J. Ethical Implications of Anticipating and Witnessing Societal Collapse: Report of a Discussion with International Scholars; Institute for Leadership and Sustainability (IFLAS) Occasional Papers; Cumbria University: Carlisle, UK, 2022; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Rashmi, K.; Kataria, A. Work–life balance: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2021, 42, 1028–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Potočnik, K.; Chaudhry, S. A process-oriented, multilevel, multidimensional conceptual framework of work–life balance support: A multidisciplinary systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 486–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Journal | Discipline | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Frontiers in Psychology | Psychology | 5 |

| Sustainability (Switzerland) | Environmental Science/Interdisciplinary | 5 |

| International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | Public Health/Environmental Science | 5 |

| Gender, Work, and Organization | Gender Studies/Organizational Studies | 4 |

| Journal of Vocational Behavior | Psychology/Career Development | 4 |

| PLoS ONE | Multidisciplinary Science | 3 |

| Applied Research in Quality of Life | Social Sciences/Quality of Life Research | 3 |

| Journal of Women’s Health | Health Sciences/Gender Studies | 3 |

| International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction | Psychiatry/Addiction Studies | 2 |

| BMC Medical Education | Medical Education | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lantsoght, E.O.L. Improving Work–Life Balance in Academia After COVID-19 Using Inclusive Practices. Societies 2025, 15, 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080220

Lantsoght EOL. Improving Work–Life Balance in Academia After COVID-19 Using Inclusive Practices. Societies. 2025; 15(8):220. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080220

Chicago/Turabian StyleLantsoght, Eva O. L. 2025. "Improving Work–Life Balance in Academia After COVID-19 Using Inclusive Practices" Societies 15, no. 8: 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080220

APA StyleLantsoght, E. O. L. (2025). Improving Work–Life Balance in Academia After COVID-19 Using Inclusive Practices. Societies, 15(8), 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15080220