Abstract

This article focuses on the story of a pirogue shipwreck that occurred in early September 2024, less than two miles from the coast of Mbour, about 90 km south of Dakar. It traces an ethnographic account of that tragic event through the lenses of different voices, standpoints, and testimonies from the survivors, the relatives and friends of the victims, and those involved in the organization of both the aborted ocean crossing and the rescue operations in various ways. By situating this extreme story of “potential migrants” among other accounts of migrants who disappeared at sea and of missing pirogues, the focus shifts to the different weights and possibilities of movement when dealing with disappearance and death, the unknown and known facts, addressing that which remains unknown even within this unambiguous and tragic event. Faced with the dense plot of ties at the core of that failed escape, we suggest that the reasons for the shipwreck are excess demand and solidarity, in terms of the impossibility of denying passage onboard the boat to friends, relatives, and neighbors. “On est ensemble” is therefore a way to recognize that there is no clear distinction or distance between captain and passengers, survivors and the dead, or victims and spectators, since in Mbour, everyone perfectly understands both the reasons and the risks, and the reason for the risks, of any illegal attempt to cross sea and land borders towards Europe.

1. Potential Migrants

Among the governmental discourses and categories employed to manage and counter unauthorized migration, the term “potential migrant” is increasingly being used [1,2]. It is currently adopted by several institutional actors, particularly at the European level (EC, IOM, Frontex), with the main aim of detecting, anticipating, and ultimately preventing the illegalized, and thus tautologically risky, departure of people. The term is increasingly applied to individuals in advance, well before their actual decision or desire to leave, as though the evoked potentiality might be asymptotically anticipated. There is a peculiar, suspicious, and actuarial attitude in profiling someone as a potential executor of an act, such as a gesture or a deed, before it is committed or, sometimes, not even conceived of [3]. Detecting such a propensity is a matter of pedagogical and sociological investigation and of knowledge, prevention, and, eventually, dissuasion. Above all, it is a matter of control [4]. All these efforts directly concern the locations of departure and involve cooperation between international and European agencies and the “potential emigration” state’s authorities and civil societies [5]. In our ethnographic field work, the term officially employed to define a potential migrant is “candidat à l’emigration irreguliere”. The French way of expressing this notion is somewhat more explicit or less euphemistic, as it directly associates potentiality with irregularity [6]. Many Sub-Saharan African countries [7] are considered to be the most targeted or affected by the phenomenon. Currently, these countries are committed to directly promoting campaigns aimed at migratory dissuasion by implementing exemplary programs for voluntary returns, denouncing the risks of “illegal migration”, repressing and punishing “the traffickers”—as well as converting the “trafficked”—and updating and repeating plans, funded by the EU, for development and cooperation among African countries to encourage and invite people to “circuler chez vous” (also “naufrager chez vous”).

Further, together with preventive efforts, the category of potential migrants implies that there is another powerful dissuasive message countering what is conceived of as an irrational drive to leave and migrate. This is the rhetoric of “retrospective conversion”, addressing those who made the “wrong choice”, which is based on institutional campaigns for returning, directly supported by both the departure and destination countries. These campaigns, which can be articulated differently on the basis of a voluntary return, either assisted or financed, have been increasingly spread among Western African countries, particularly in Senegal [8,9,10,11]. In fact, this country represents a somewhat over-studied site for its migration processes, as well as for socio-anthropological research [12,13,14,15,16,17], while its capital is a vibrant hub and arguably the cultural epicenter of all of Western Africa. Nonetheless, rather than directly addressing the migration dynamics and policies that have affected the country in the last few years, this contribution focuses on the increasing violence characterizing the direct and indirect ways that migration from Senegal is managed or governed by both the state authority and international—mainly European—actors. In other words, it is a matter of exploring the ways in which almost any form of egress from the country is driven underground and made irregular, unauthorized, and as such, illegal [18] at a time when the material reasons to leave are growing, and leaving the country still appears to be the only choice. As ethnographers, we tried to reconstruct such a violent process (of criminalization and illegalization) through the perceptions, stories, lenses, and standpoints of those who, at different levels, directly participate in these attempts to leave.

Indeed, there exists a rising pressure that acts as a kind of “culture of terror” [19] hanging over anyone—man or woman, young or old—who, at different times, under different conditions, and despite all odds, decides to leave, usually overnight. This pressure, in turn, makes the journeys increasingly hazardous and risky, often tragically lethal, by further reducing both the space–time and possibilities for potential migrants. In Senegal, as elsewhere in West Africa, all the stories of “illegalized” migration are surrounded by and permeated with loss, death, and disappearance, making them a kind of “space of death” [19]. Here, while participating in the growing debate on failure, loss, and grief in migration [20,21,22,23,24,25], our specific aim is to deepen the ways that individuals, families, and local communities perceive and describe such a “space of death”, reorganizing their constantly precarious lives and facing the intimate and material damages inflicted by border politics and illegalized migration rhetoric. This in turn suggests the need to take into account another relevant body of literature, one that is focused on different forms and practices of solidarity, by considering the latter as a driving force in unauthorized migrations [26,27]. Rather than conceiving of it as an external support to migrants, we suggest a somewhat materialistic notion of solidarity, along with the specific theoretical framework derived from the idea of the autonomy of migration [28,29], envisaging it as a form of mutual aid at the grassroots level, encompassing both social and political empathy, as well as a form of mutual exchange through economic personal interests [30].

In these pages, we will primarily deal with a particular and extreme case of potential migration, as well as that of “involuntary return”, addressing the tragic case of a shipwreck that occurred just after departure in early September 2024 less than two miles away from the coast of Mbour, a Senegalese town about 90 km south of Dakar.

Along with this singular event, we encountered other stories of disappearance and death involving boats, migrants, fishermen communities, and local and state authorities that further expand and complicate the picture.

Once we arrived in Senegal, our main intention was to identify the impact of the new politics adopted both at the EU and state levels to counter what is defined as “illegal migration and smuggling” [31], particularly focusing on their effects on local communities and the population, that is, addressing the perceptions and reactions of individuals and families whose material living conditions were progressively worsening and who were forced to witness and participate in a relentless exodus that was increasingly countered by authorities.

The main research questions were therefore the following: (1) How do the local people, survivors, and friends and relatives of those who left perceive and describe what is officially defined and criminalized as smuggling? (2) How do people react to the increased tightening of border policies adopted at the national/international level and to the necropolitical effects it implies in terms of loss and disappearance? (3) What kinds of social relations, family ties, solidarities, and mutual aid are involved in the organization of an unauthorized journey through the maritime route towards the Canary Islands and Europe?

The recent history of Senegal and, more generally, the Atlantic Route is beleaguered by tragic events involving disappearance, loss, and death during migration, to the point where clear accountability seems impossible [32]. This is also true for the case considered here: a shipwreck occurred before the eyes of a whole city, and its toll remains obscure even several months thereafter. Yet, though there exist many unresolved questions about the entity of that tragic event, no one in Mbour, nor in the country as a whole, wonders about the reasons and material motives that led to the shipwreck: the distance between the fog surrounding the toll of this disaster and the clear understanding of the reasons that led to it is, thus, the main theoretical and political question addressed in this article. They resonate as a kind of common knowledge, as something taken for granted among the people we encountered, something broadly recognized in public discourse.

2. Ethnographic Insights

This article is based on ethnographic research carried out in Mbour and Joal during the month of December 2024; in this period, we met and talked with several fishermen and captains, potential migrants, and local authorities, along with a number of passengers who survived the shipwreck and many of the relatives of the victims and missing people. Furthermore, a second field study was conducted in March 2025, which deepened our knowledge of fishing and coastal communities in Senegal and maintained our relations with informants in the two main locales of our research. In both research periods, we had 40 ethnographic encounters, the majority of which have been recorded and filmed according to a visual sociology approach [33]; as a result, the material collected will also contribute to the realization of a filmic research series on migrants’ Atlantic route. Most of the encounters took place in domestic dwellings—the houses of the survivors and the relatives of those who disappeared—and in all cases, the people we encountered perceived us as a resource for seeking truth and justice. The selection criteria were based on the need to gather multiple witnesses of the events that we aimed to reconstruct, the availability of the interviewees, and their willingness to turn their personal grief into a public story.

Following a narrative approach to ethnographic writing [34,35], the text is mainly based on different encounters and dialogues between us, as researchers and storytellers, and the various actors connected to the shipwreck (Figure 1). The main aim was to collect different accounts, perceptions, and standpoints about that event, focusing on its meaning, relevance, and impact, and to assess the role and significance of solidarity networks in the context of illegalized migration [36]. Accordingly, we decided to retain French in some of the conversations with the people we met to respect how they chose to address us and to convey a series of differences (the majority of people, even if they understand French, do not speak it and prefer Wolof), as well as their particular way of inhabiting an overlapping and imposed language, a colonial legacy that still defines Senegalese society. Many of our informants chose specific words in French to tell us their versions of the facts, their moods, and their stories, usually without particular effort, and we deemed it necessary to preserve and convey their voice. In all these cases, the text reflects their voice, and it is translated into English in parentheses.

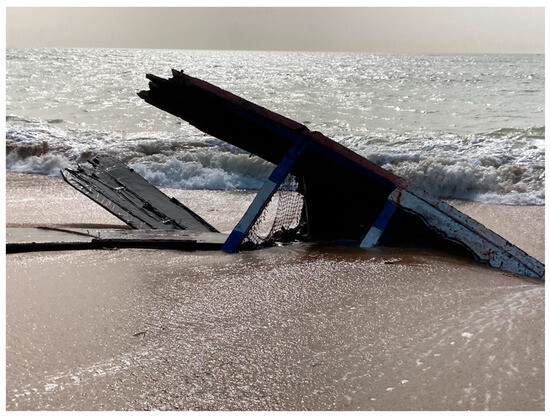

Figure 1.

What remains of the wrecked pirogue. Source: the authors.

3. A Shipwreck with Spectators

“C’était une dimanche soir, vers 6 heure or 6 h 30. Je ne me souviens plus de la date, une dimanche du début septembre. Il y a environ trois mois.

And how was the pirogue, was it good?

Oui, c’était une tres belle pirogue, en bois solide et de qualité. Nous sommes allés pêcher en Gambie et jusqu’en Guinée Bissau en mois juillet, tout s’est bien passé.

But how many of you were there that time?

Douze, je dirais.

And how many were there the day of the shipwreck?

Je ne sais pas exactement, plus d’une centaine, c’est sûr”.

(“It was a Sunday evening, around 6 or 6:30. I don’t remember the date, but it was a Sunday in early September. About three months ago.

And how was the pirogue, was it good?

Yes, it was a very beautiful canoe, made of solid, high-quality wood. We went fishing in Gambia and as far as Guinea-Bissau in July, and everything went well.

But how many of you were there that time?

And how many were there the day of the shipwreck?

Twelve, I’d say.

And how many were there the day of the shipwreck?

I don’t know exactly, but more than a hundred, for sure.”)

This conversation, with a few words muffled by the noise of the waves and the wind, took place on a sandy beach somewhere halfway between Mbour and Joal in mid-afternoon. We were walking on the foreshore in front of the wreck of a family pirogue, behind the palm-grove of an exclusive hotel operated by a Spanish chain, Riu, from Majorca. Cher Issa is about twenty years old, and he is still a student at the high school in Mbour. We were a bit surprised to find him dressed in a school uniform when picking him up: he seemed much older, more adult. Just two days before, when we first met Issa in his family’s house and asked him whether he could show us the wreck, he answered without hesitation, but in a shy, kind way. His French is educated, high school level, but few words were uttered concerning the story, just embarrassment and grief. It is a tragic story: a shipwreck, a missing brother swallowed up by the sea, and a father in prison.

The shipwreck that transpired in the open sea of Mbour on Sunday, September the 8th is also the story of a whole family’s shipwreck, Cher Issas’s, and of a neighborhood in that city, specifically a street—two or three houses.

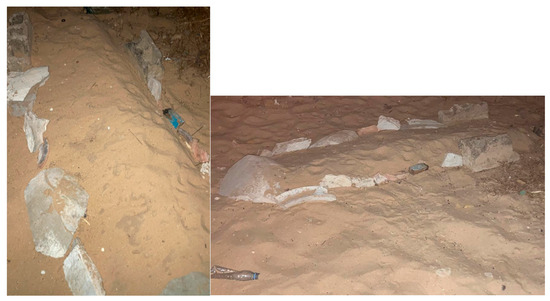

Actually, even the location of the washed-up wreck was a surprise to us due to a slight misunderstanding. We had erroneously understood that the boat was found in front of Mbour near the hotel where we were staying, where the sea had returned several unidentified corpses that were then buried overnight and anonymously, with a few stones scattered around the beach to cover and signal the presence of bodies without names (Figure 2). People say there are other hidden and anonymous graves all around—more corpses, more dead—but we just saw the two nearby, at night, in the dark amidst the brambles, having been driven there by two kids we encountered in front of the hotel. We thought that the pirogue had followed the same trajectory.

Figure 2.

Anonymous grave on the beach of Mbour. Source: the authors.

“And so, what happened that day, that Sunday?”

“Tout semblait bien se passer. Il y avait beaucoup de monde qui étaient embarqué toute la journée d’autres pirogues plus petites. Tout semblait bien fonctionner.” (Everything seemed to be going well. There were a lot of people embarked by smaller canoes all day long. Everything seemed to be working well.)

Issa is meticulous in recapitulating all the embark preliminaries:

“On est venu ici pour se préparer. On a acheté tout ce qui est possible. On a acheté tout, on a préparé tout. Tout était normal. Dans les cinq jours qui avancent, la pression monte. Parce que ce n’est pas que tu prends la mer pour traverser chaque jour, la pression monte. Mais le jour où tout se passait très bien, on a accueilli les personnes qui devaient y aller. On a tout fait normalement. On l’a géré normalement, comme il se doit.” (“We came here to prepare. We bought everything possible. We bought everything, we prepared everything. Everything was normal. As the five days went by, the pressure mounted. Because it’s not that you’re taking to the sea to cross every day, the pressure mounted. But on that day everything was going very well, we welcomed the people who were supposed to go. We did everything normally. We handled it normally, as it should be.”)

And then what happened, and why?

“Pour moi, la cause, c’est les passagers. Parce que les 70%, on peut dire les 80%, ne savaient rien sur la mer. Ils n’ont jamais parti à la mer pour pêcher ou bien pour se nager. Ils ne connaissaient rien à la mer. On est partis vers 18 h. On a démarré le moteur. Une minute, deux minutes. Il y a le vent qui ne nous laisse pas passer tranquille. La pirogue faisait comme ça, (he slants his palm) mais les passagers n’écoutaient pas. Parce qu’on leur a dit de rester tranquille. S’ils se posaient tranquille, on va gérer la situation. C’est-à-dire qu’on va gérer la pirogue. On va passer tranquillement. Mais eux, ils n’ont pas écouté. Une pirogue, de 100%, les 70% ou bien les 80% vont sur le même côté. La pirogue n’aura pas d’équilibre. C’est ce qui a causé le naufrage. Parce qu’on est sur la mer. La pirogue n’est pas équilibrée. Les 70% ou bien les 80% se sont déplacés pour fuir l’eau. Parce que l’eau est entrée. On est croisés avec le vent. Ils ne voulaient pas se mouiller. Après, ils sont partis tous de même côté. Ce qui a permis à la pirogue de se renverser de l’autre côté. Quand on croise le vent, la pirogue bascule. L’eau entre. Les 70% ou bien les 80% fuirent dans l’eau.” (“For me, the cause is the passengers. Because the 70%, or we could say the 80%, knew nothing about the sea. They had never gone to sea to fish or to swim. They knew nothing about the sea. We left around 6 p.m. We started the engine. One minute, two minutes. The wind wouldn’t let us pass quietly. The canoe was doing this, (he slants his palm) but the passengers weren’t listening. Because we told them to stay calm. If they landed quietly, we’d manage the situation. That is to say, we’d manage the canoe. We’d pass quietly. But they didn’t listen. A canoe, 100%, the 70% or the 80% go to the same side. The canoe won’t be balanced. That’s what caused the sinking. Because we’re on the sea. The canoe isn’t balanced. 70% or 80% moved to escape the water. Because the water got in. We crossed paths with the wind. They didn’t want to get wet. Then, they all went in the same direction. This allowed the canoe to overturn to the other side. When you cross paths with the wind, the canoe tips over. The water gets in. 70% or 80% disappeared into the water.”)

Amidst a barrage of numbers and percentages, the shipwreck is blamed on the unpredictable behavior of the passengers—their fear, panic, and lack of familiarity with the sea.

“But how was the atmosphere, the mood on the boat while waiting for leaving, before the tragedy?”

“C’était bien, on était tous pleins d’énergie, de joie, beaucoup d’espoir… J’ai rencontré beaucoup de gens que je connaissais déjà, à bord, pas tous mais beaucoup. Certains que j’ai rencontrés après longtemps, la majorité que je ne connaissais pas et que je n’avais jamais rencontrés auparavant, ils venaient probablement d’ailleurs, de l’intérieur des terres, avec d’autres que j’avais l’habitude de fréquenter, ils m’étaient familiers, ma famille, mes meilleurs amis. J’ai perdu un frère, même père mères différentes, un cousin et mon meilleur ami ce jour-là.” (“It was good, we were all full of energy, joy, a lot of hope… I met a lot of people I already knew, on board, not all but a lot. Some I met after a long time, the majority I didn’t know and had never met before, they probably came from elsewhere, from the interior, with others I was used to seeing, they were familiar to me, my family, my best friends. I lost a brother, same father different mothers, a cousin and my best friend that day.”)

Issa is the son of the pirogue owner and was also one of the two captains of that journey. His father, Cheikh, spontaneously consigned himself to the local authorities after the shipwreck. International media had erroneously reported that he was a relative of the city mayor, who in turn was considered directly involved in the organization of the crossing. Arguably, it was just a matter of homonymy, more likely of a remote kinship. However, this lapsus, if it is one, sounds at least symptomatic of the dense plot of family ties and relationships characterizing this tragic (and ordinary) story of an (extraordinary) shipwreck, one among many, known and unknown, whose main anomaly consists in its occurrence in front of the site of departure, just after departure, virtually before the eyes of everyone, less than two miles away from Mbour shores.

This is not an unsolved mystery of a disappearance; rather, it is a shipwreck with several direct witnesses, survivors, and spectators. As such, it is an undeniable fact, a matter of fact that seems to leave no room for other words or stories to be told, no hope of confutation, no way to imagine otherwise that would prolong or refute this lethal event, just the steady trickle of corpses returned by the sea.

Nevertheless, even in this case, there are differences among the bodies—different trajectories, positions, epilogues, and forms of disappearance—as much as there were differences and different conditions among the passengers, amidst all the potential migrants who embarked on the shipwrecked pirogue.

4. The Passengers

Indeed, Issa talks about a list his father had made with the names of all the people onboard. That list likely disappeared in the shipwreck, together with x people (the number of dead and missing is still uncertain), the pirogue, and all espoir—the hopes, expectations, and joy—it could have contained.

“Oui, il y avait une liste pour connaître… Parce que tu ne peux pas connaître tout le monde, voilà. Il y avait une liste. Parce que cette liste va vous montrer ceux qui ont déjà donné de l’argent et ceux qui n’ont pas encore donné de l’argent.” (“Yes, there was a list to know… Because you can’t know everyone, that’s it. There was a list. Because this list will show you those who have already given money and those who haven’t yet given money.”)

The list did register all those who had embarked, as well as the different travel conditions among them and the diverse arrangements and agreements they drew up and stipulated with the pirogue owner.

“[…] il y avait des personnes qui ont payées casse. Il y avait des personnes qui ont donné la moitié. Et il y en a des personnes qui n’ont rien du tout.” (“[…] there were people who paid in advance. There were people who gave half. And there are people who got nothing at all.”)

Among the first group of passengers, there were many people coming from elsewhere, the majority of whom were from other villages or cities. Issa suggests that they were mainly unknown strangers from the interior, perhaps even from Touba, who did not know anything about the sea, neither fishing nor swimming. They had paid the whole price in advance in cash, and they are likely to have drowned and perished. The second group was formed mostly by people from Mbour and its immediate surroundings, with a certain knowledge of the sea and often a personal, direct relationship with the pirogue’s owner. They might have arranged a downpayment as a form of credit, a partial deposit to be completed once they arrived in the Canary Islands, Spain, Europe, the final destination. The third group was made up of friends, relatives, or those familiar with the pirogue owner or the other captain, and they did not pay anything, at least not in advance.

Still, despite the undeniable evidence of the tragedy, it is worth repeating that the exact number of losses remains uncertain, reflecting the haze surrounding the number of people who actually embarked that day. Two different statements attributed to the pirogue’s owner, Issa’s father, reflect this opacity. In the first and officially recorded one, he maintains that “Avant le départ, la pirogue contenait 86 personnes, des amis et parents qui m’ont contacté pour que j’embarque leurs enfants. Mais des gens arrivaient et montaient à mon insu. Ce qui a fait évoluer le nombre de passagers” (see https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/59765/senegal--le-bilan-du-naufrage-passe-a-29-morts-et-toujours-des-dizaines-de-disparus—accessed on 1 February 2025). In a second and vaguer one, he speaks of “au moins 150 passagers” (see https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20240910-s%C3%A9n%C3%A9gal-le-capitaine-de-la-pirogue-qui-a-fait-naufrage-au-large-de-mbour-arr%C3%AAt%C3%A9, accessed on 1 February 2025). Yet, these two phrases, uttered by a charged man, and the blank space between them suggest something more, a possible hint about the cause of the shipwreck, as though it was caused not only by the inexperience and unwise behavior of the passengers (as well as of the organizers), nor only by the conditions of the sea that day, nor by the will of God (as many survivors and relatives of the victims stress), but also, if not mainly, by the massive overcrowding of the boat (more than 150 people on a 20 m pirogue), due, in turn, to the impossibility of denying the journey to anyone. In a way, though articulated differently among unknown customers, acquaintances, friends, and relatives, it seems there was an excess of “demand”, that is, of pressures, of social, personal, and familial relations and ties, and thus a sort of “excess of solidarity” [37] that greatly overwhelmed and overloaded the pirogue’s actual capacity and size.

Certainly, speaking of such an excess may sound like a way for the journey organizers to deny that they bear any direct personal responsibility and, thus, a way to defend themselves from the charge of superficiality, inexperience, and particularly greed in knowingly overcrowding the boat. This might be the case, and it might also be a way for them to deal with the weight of this tragedy, with the shame and deep sense of guilt. Yet, to reduce and isolate that fact to a singular (anonymous, impersonal) factor, even to conceive of it as just a matter of personal hazard, an error, a fault, or an act of greed and avidity, is somewhat misleading, since it has been essentially a collective enterprise, a familiar and community tragedy in its premises, conditions, effects, and affects. In addition, except for a single voice, a passerby met near the relict who directly condemned that story as crazy, insane (“c’était un suicide”), no one else among the spectators, the survivors, or even the victims’ relatives whom we met actually blamed the captain. On the contrary, they all manifested a rather sympathetic attitude, implicitly discharging him and his family from any real responsibility. Facing this broad lack of resentment, we first interpreted it through vaguer psychological categories, such as general acceptance, resignation, or fatalism. However, although fatalism—as the acceptance of the fate, the will of God—is frequently evoked and identified by our interlocutors, it seems at least a rather generic and reductive answer if compared to the huge set of social ties and relations actively involved in that story. As such, as a community and neighborhood event, it was instead understood as a collective shipwreck, one in which several relatives, friends, witnesses, and spectators directly participated and whose real extent remains unknown, somewhat obscure.

5. Those Who Died, Those Who Disappeared

While the overall number of victims has always been uncertain, a week after the shipwreck, the number of recovered corpses had reached 41, and the number of rescued people amounted to 43. Although there is no evidence, it is likely that the majority of the victims were among those coming from elsewhere, whose presence onboard remained mainly unregistered, unknown (in most cases also by their very families), and thus invisible. A different destiny awaited the recognized bodies. Among them, the majority (mainly the locals) were buried after a funeral in a graveyard in Mbour, Libertè, while a few others were returned to their places of origin. In addition to these ritualized forms of leave-taking, there remains an uncertain number of unrecognized corpses anonymously buried near the shores where the sea returned them. However, if we consider that, among the allegedly 150 people onboard, more than 100 have not been found, and only 41 have been officially buried, the majority remains part of the overall “dark number” of bodies without names, names without bodies, and the ghostly presence (and absolute absence) of those with neither a name nor a body.

Of course, death and disappearance are not the same thing [38]. There are stories of disappearance, of missing men, women, boats, and pirogues, that may allow one to imaginatively and tenaciously confute or refuse the idea of death, of a definitive and ultimate end [39]. Yet, these stories of absence, their particular sense of “lessness” [40], are by definition undefined and unknown, forcing one to face the weight of an uncertain, open-ended, empty yet heavy waiting time. As stories of absence, they can also be ignored, unnamed, and uncounted, deprived of proper histories, places, biographies, and bodies, while haunting and hanging over those, mostly unaware, who survive and wait. If disappearance can oppose and counter death, it always does so in a void, and that absence further complicates these stories “not to pass on” [41], providing them with further (im)positions and (im)possibilities. In other words, preventing people from facing the idea of death, that is, bodies with names and graves, compels them to deal with names without bodies and corpses without names, as well as with ghosts—presences/absences that have neither a body nor a name.

Certainly, all these stories, these ghostly presences and absences, arose together, on the same day, Sunday, September the 8th, and on the same pirogue shipwrecked before the eyes of a city. To all this, it must be added that, luckily, there are also survivors, such as Issa, and many witnesses—almost a whole city. They all have a specific position, their own view on that fact, which can only be reductively defined as fatalistic.

6. Those Who Survived

Issa is a survivor and a witness, as well as someone directly involved in this familiar enterprise or family shipwreck that is also a neighborhood shipwreck. Two days before going with him to the pirogue wreck, we had been in the house of another family of survivors, always in the fishermen’s neighborhood of Mbour. There we met Awa (fictitious name), 27 years old, who was washing clothes in the middle of a yard under two large mango trees. She talked to us as she continued to work, moving clothes from one bucket to another, from dirty water to the clean one. Her child wandered around the buckets, bored, while her mother-in-law, sitting, was watching and listening to us talking. Awa asked us to wait for her husband, also a survivor, before we recorded the interview, but meanwhile, she told us her version of the story. She perfectly understands French, but she speaks in Wolof, translated by our colleague and guide Babacar, who in turn explained to us that she first said the pirogue was organized by her neighbor, the shipowner and captain, who comes from a family of fishermen. Like others in the neighborhood, she did not pay anything but committed to repay around CFA 200 thousand once she started working in Spain. Her account of the shipwreck sounds more detailed than Issa’s, probably because of her greater distance, that is, her lesser involvement in the enterprise. She remembers that she and the other passengers arrived at the big pirogue via another smaller one from the beach, in broad daylight. Everyone knew, everyone saw: nothing to hide. Besides her, there were only six other women, and they were all brought there in the space normally designated for the fish, a privileged treatment. Yet, as soon as they boarded, some of the women started to vomit and became upset. Four of them would die or disappear that day. Then, without being solicited, she added that the captain was afraid until the very end that the boat would not hold. He was hesitant about whether to cancel the trip. In the end, he decided to return to the beach with all the passengers. However, it was too late: the boat capsized in the evening, having stopped a few miles from the coast, due to panic and a sudden wave.

We did not further verify her version of the facts, specifically whether the captain had eventually decided to give up and come back, although Issa would later confirm her words. What emerges clearly is that Awa is not angry with anyone. On the contrary, she offers some benevolent words for the pirogue owner, Issa’s father, despite his imprisonment. “He is the one who saved me, kept me close and put me on the top of the overturned pirogue”. Even her husband, Mass, shares this lack of resentment, melting it into a mix of fatalism (“I am not different from those who died. Why did I survive?”) and a sharper consciousness: “there are no alternatives to the pirogue, many among those who died, as my best friend, had tried to apply for a visa. But it is impossible, visas are inaccessible”). They were supposed to go to France, where they have relatives. “Now I can’t see the sea anymore, those images come back to me.”

It is likely that their lack of resentment and willingness to defend and absolve the pirogue’s captain, together with a general sense of resignation, reflects a broader proximity characterizing the relations among the owner and many other passengers like them. It is at this point that we realized that the house of the pirogue’s owner was just in front of Awa and Mum’s. They pointed at it as though suggesting that this story is confined to the perimeter of a family pirogue. Yet, the pirogue seems to be a much more complex object than that of mere family ownership. It is a universe made up of different social circles, whose totality lies in concentrating in itself and shedding light on a whole and more articulated set of political, economic, personal, and kinship relations: the family of the owners, those of the neighbors and of the whole neighborhood, the inhabitants of Mbour, and finally, the Senegalese from the inland and the foreigners. All these circles reflect, in turn, different forms of exchange and material conditions for the passage: the first ones travel for free, the second ones rely on credit, and the third ones pay in advance. These different levels and layers define a radius of distance and proximity, with the pirogue at the center, as a socio-economic means of regulating forms of reciprocity and exchange that metonymically seem to define the economy of a broader society whose sustenance largely relies on fishing. For these reasons, the pirogue ends up representing an overall time–space, a political and social “chronotope” [42], one that, not by chance, gives the name to a whole country, Senegal, from the Wolof “sunu gaal”, which means our pirogue.

7. The House of the Ship Owner

After leaving Awa’s place, we were in front of two houses: a poor and decaying one on the left and a shiny white one, repainted and taller, with three floors and glass windows, on the right. At first, we assumed that the pirogue owner’s house was the more expensive and newer one, but we were wrong. Having a pirogue, organizing passage to Europe, which is more than an entrepreneurial activity, is a matter of proximity and community bonds, which do not exclude an economic transaction, an exchange, or a commitment to return, but usually encompasses common or analogous shared material conditions.

Outside Issa’s father’s house is a small grocery store. The young owner tells us that he lost his brother, who came from Touba, in the shipwreck. He was 21 years old, and he, too, had left on credit. In the narrow space of three houses, three doors, it is possible to encounter three different forms of involvement.

From there, we entered the house of the family of the fisherman who organized the passage: Issa’s house. On the left is a pen for a goat. There are many daughters and young women, as though only the women are left. A plate of food is passed around through everyone’s hands. Inside the house it is dark. They let us sit on a bed in a small room, in front of a TV screen. Gradually, the room fills up, becoming a sort of assembly: in front of us are the wives of four people who died in the shipwreck and two survivors. They are all members of the same family. A woman asserts with emphasis that they are not criminals, not traffickers, just fishermen, and that they themselves were traveling to find a better future, that they themselves have lost their beloveds and everything, also a pirogue.

Yet, although departure is the outcome of a neighborhood cooperation, acquiring, as such, considerable social legitimacy, the grief and the sorrow, according to the widow’s story (also named Awa), remain individual and familial. “We did not feel supported by anyone, only from the family” (she then mentions only a psychological support service offered by DDM, a Spanish NGO linked to Caritas). However, even in this case, there is no sense of guilt, nor anger or resentment among the neighbors and the families of the dead and the missing, nor from those survivors who relied on that pirogue to leave. What remains after the shipwreck is just a massive sense of absence and poverty: a boat that no longer exists and fewer arms to bring income home to a family comprising only women.

Two days later, this specific sense of desolation would be reasserted by Issa, who, in front of the wreck of his father’s pirogue, would speak of a specific “deception” that, in his case, sounds more like a mix of chagrin and sorrow than disappointment.

“Je ressens un peu de la déception. Parce qu’il y avait une confiance totale en mon père. Parce que tous les passagers qui étaient là-bas, ils disaient que c’est lui, c’est lui. Ils avaient une confiance aveugle envers lui. Parce qu’ils le connaissaient. Ils le connaissaient, c’est son métier. Il est dans la mer depuis son enfance. Il a grandi là-bas. Après, quand tu vois qu’il a échoué, c’est la déception. C’est la déception, franchement. Oui, c’est dur. Pour ceux qui travaillent dans la mer, c’est difficile. C’est toujours difficile.” (“I feel a little disappointed. Because there was a total trust in my father. Because all the passengers who were there, they said it was him, it was him. They had blind faith in him. Because they knew him. They knew him, it’s his job. He’s been at sea since he was a child. He grew up there. Afterwards, when you see that he failed, it’s disappointing. It’s sad, frankly. Yes, it’s hard. For those who work at sea, it’s difficult. It’s always difficult.”)

Yet, such a “deception” or desolation does not entail any sense of shame, responsibility, or guilt. On the contrary, even the loss melts into a broader common and desolate condition, as well as into a form of mutual comprehension and solidarity.

“Je me sens bien maintenant dans le quartier. Je suis toujours avec mes amis. Il y en a certains qui ont perdu leurs frères. Mais ils ne me regardent jamais comme ça. Ils me regardent comme ils me regardaient avant. Ils me comprennent très bien. Ils savent que j’ai une douleur profonde. Mais voilà, ils me supportent.” (“I feel good in the neighborhood now. I’m always with my friends. Some of them lost their brothers. But they never look at me like that. They look at me like they used to. They understand me very well. They know I’m deeply hurt. But they support me.”)

8. The Missing Pirogue

Joal is another departure point along the coast moving southward, one hour’s drive from Mbour. It is a fishing village, like so many others: like so many others in crisis because of the crisis of artisanal fishing [43]. Many families of the village are involved in the story of a missing pirogue that left on 30 April 2024 with 125 passengers onboard (Figure 3); many passengers were local, others came from Casamance, Ghana, or Gambia. We speculate that this one was also a family pirogue of neighbors and acquaintances, with a share of strangers paying to cover the initial expenses: a mixed pirogue. We meet a woman whose brother disappeared. She tells us almost nothing; she does not want her story recorded. She works in fish sales, and her brother was a fisherman. We only learn that poverty has increased as a consequence of the missing pirogue and, once again, weighs on those left behind: women and children. Those who had to leave to support their families from abroad are no longer there; in this sense, the difference between dying and disappearing, in terms of the family economy, is irrelevant.

Figure 3.

Claire shows us a screenshot of the missing pirogue. Source: the authors.

In another house, we meet Claire (fictitious name). She, too, has a fisherman brother who is missing. She is 33 years old and studied sociology at an online university; she is Catholic and has no children. She recently finished research on migrant deportees funded by a Western institution with the aim of stopping departures. We ask her what conclusions or feelings she has drawn from the study: “They will leave anyway,” she tells us. “S’ils voient une pirogue, ils monteront à bord et partiront, même s’ils ont vu et vécu des choses terribles.” (“If they see a pirogue they will get in and leave, even if they have seen and experienced terrible things.”) Claire has just completed a one-year volunteer scheme with the Africa Corps in a remote village in Casamance; she is enthusiastic about the experience and tells us about the importance of local development, where the community decides together what the priorities are.

She tells us that her missing brother had already tried to cross once but was rejected by Mauritania. According to Claire, the responsibility lies with the individual: “C’est un grand garçon, un adulte. Il a pris une décision qu’il n’a communiquée à personne.” (“He is a big boy and an adult. He made a decision that he did not communicate to anyone”.)

All around, there are many families, one house attached to the other, that are in the same condition: they help and support each other, above all, and they cling to different tracks to find their loved ones. Death is never mentioned since the bodies have not been found. In contrast to the Mbour shipwreck, here hope is at work; the story remains open.

This position seems unrealistic to us: how can 125 people still be alive when, in eight months, there has been no sign or news? Yet, in conversations, we are careful to never use the word “dead”. If they are not yet dead, if the story is open, there can be no judgment to assign blame. Claire, in fact, is not angry with anyone. As with the shipwrecked pirogue, people cite God, fate, destiny, or the individual. Here, however, compared to the (still uncertain) narrative that has been told in Mbour, we have a different story, a different drama or tragedy; we are dealing with the missing, with ghosts considered to still be alive, quite the opposite of the evidence of a shipwreck and the materiality of corpses recovered on the beach of Mbour. Yet, the everyday life and familiar dimension of the experience reflect a certain synchronicity and heterogeneity: in every house is someone who has disappeared, someone who has died at sea, someone who has managed to leave, someone who is on the other side and who, according to Claire, fuels the desire for departure for those who remain.

Beyond the underlying fatalism, among the families of the missing, the symbolic function is to keep the story open: we note the proliferation of rumors, handholds to latch onto, hopes that can and must be nurtured. We move to the house on the side, and here, too, a mother has two daughters who were on the missing pirogue, with their husbands and their babies, only a few months old. A total of six people are missing. The woman says, “It was a family pirogue. We didn’t know they were leaving”. Many tell us that they did not know; perhaps it is their way of easing the pain and family responsibility for a choice that is always legitimized by those who make it as a duty of solidarity to the family. In her story, first el Hierro in the Canary archipelago is cited as the place where the pirogue arrived, then Tunisia, and then Assamaka in Niger, where deportations from Algeria run aground; it is a geography gone mad. Babakar, a local activist for the freedom of movement, tries to give a short lecture by describing maps and borders. He tells her, “I have never heard of a pirogue crossing the Strait of Gibraltar. It couldn’t have made it to Tunisia”. But the woman nods without conviction. From the fishing district of Joal, despite shipwrecks and disappearances, despite institutional and international campaigning efforts, and despite the risks of undocumented migration, people continue to leave; resignation manifests in failures, while imagination and obstinacy pave the way to the future.

While the previous woman had constructed an impossible geography to keep her beloved ones alive—a pirogue crossing the Strait of Gibraltar and arriving in Tunisia only to be deported to Niger—Marie (fictitious name), an elderly mother, evokes a story from the past to make sense of the present. She welcomes us into her home—next to the previously visited ones—in a large room furnished with sofas: we can see that more resources circulate, or were circulating, here. Marie stands in the center of the space and begins to speak like a fortune teller in perfect French. She makes us listen to a mysterious recorded message (from an unspecified person who had delivered it to a neighbor) in which an unknown voice speaks of an interception at sea by the Moroccan navy and a helicopter. She then says emphatically, “Je le sais. Ils sont à Agadir, ils sont esclaves dans les champs” (“I know. They are in Agadir, they are slaves in the fields of agriculture.”). Adding: “Rendez-nous nos enfants, ils ont été kidnappés, nous sommes de retour à l’époque de l’esclavage des Noirs. Pourquoi ?” (“Give us back our children, they have been kidnapped, we are back in the days of black slavery. Why?”) Marie has three children in France, while the fourth was waiting for a visa that was not forthcoming and had decided to join them in the pirogue. “Il m’a demandé ma bénédiction avant de partir. Il était diplômé et ne trouvait pas de travail.” (“He asked me for a blessing before leaving. He was a graduate and couldn’t find work”.) Then she shows us a photo of her son in France and her grandchildren, one white and one black. We ask Claire whether she knew about this mysterious message; she herself is amazed. For Babacar, it is a far-fetched story.

What forms of solidarity hold these families together? First is a culture of emigration that is rooted in the neighborhood and is inscribed in everyone’s biographies. People of the village have left together, often on credit, because the others, the foreigners, pay in advance. People are in solidarity because they share a common interest: escaping the crisis of artisanal fishing and guaranteeing the lives of those who remain. In the face of the missing pirogue, the solidarity of those who remain consists not only in undertaking every possible search but, above all, in keeping alive the stories that can keep alive hope that the missing beloved will return.

9. Echoes from the Rescuers

Every tragic event needs a form of collective recognition or legitimacy to be recorded as a common story; otherwise, it remains a largely private fact. All the stories, versions, tales, and legends surrounding a missing pirogue or a missing son that were told to us in Joal were shared only by a few relatives within a single neighborhood, and they were scarcely recognized as a public account, instead remaining closed and confined to a private and uncertain domain, something in between memory, hope, and pursuit, as a “story not to pass on”. The case of the undeniable shipwreck in Mbour seems to be different, with all its victims, survivors, witnesses, and spectators, and has inevitably become a public reality. But is it really a common story? Although public, it, too, remains somewhat in the dark and in the shadows, but which darkness and whose shadows?

On one of the last days of our stay in Mbour, we went to the local Maison de la Ville to meet Mouhamadou Fall, who is the president of “partenaires migrants”, a national association whose main activity is assisting returned and potential migrants, those persuaded to come back and those to be dissuaded from leaving: “nous encadrons et accompagnons les migrants de retour, et les potentiels migrants”. He does not add anything about the contradictions and opposite directions between the two different (one actual and the other literally potential, both fictive) governmental categories, just mentioning a broader government shift: “En fait, les questions qui nous préoccupent le plus, présentement, c’est que le nouveau régime nous dise clairement quelle est sa politique migratoire.” Mouhamadou is also the official responsible for the urban market, the president of the Mbour fishermen association, and a fisherman himself. As such, he was directly involved in the rescue operations after the pirogue shipwreck in early September, and he wants to talk about that fact, from the specific standpoint of a fisherman.

“Nous avons connu au mois de septembre un naufrage qui restera gravé dans la mémoire de la communauté des pêcheurs. Parce qu’en fait, vous vous levez au bon jour et l’information circule comme quoi qu’il y a un accident qui s’est produit à 3 kilomètres au large des côtes. Des pêcheurs qui étaient allés pêcher ont rencontré la pirogue qui a fait l’accident et tout de suite ils ont informé la communauté. C’est ainsi que les gens se sont organisés pour prendre d’autres pirogues pour aller rejoindre la pirogue qui a fait l’accident et essayer de secourir les naufragés. Tant soit que nous avons pu, avec les moyens du bord, essayer de venir en aide, nous avons repêché beaucoup de survivants, mais véritablement nous avons comptabilisé beaucoup de morts. Parce qu’il n’y avait pas suffisamment de moyens humains pour faire ce genre de travail.” (“In September, we experienced a shipwreck that will remain etched in the memory of the fishing community. Because, in fact, you wake up on the right day and information circulates that there was an accident that occurred 3 kilometers off the coast. Fishermen who had gone fishing encountered the canoe that had caused the accident and immediately informed the community. That’s how people organized themselves to take other canoes to go and join the canoe in danger and try to rescue the shipwrecked people. As much as we were able, with the means at hand, to try to help, we recovered many survivors, but truly we counted many deaths. Because there were not enough human resources to do this kind of work.”)

He insists on the lack of means and assistance in rescue operations, as opposed to the rhetoric of hyper-financed programs of dissuasion for potential migrants:

“Parce que le secours c’est un travail, et ça aussi demande une formation. En tout cas, nous n’avions pas la formation et la compétence requises pour intervenir dans des situations de catastrophes pareilles.” (“Because rescue is a job, and that too requires training. In any case, we didn’t have the training and skills required to intervene in situations of disaster like that.”)

On the contrary, Mouhamadou emphasizes the self-organization of a rescue at the grassroots level: “Mais tant soit que la majorité de la communauté s’était dépêchée, ils se sont organisés pour essayer de venir en aide le temps que l’état central puisse prendre des décisions et envoyer des équipes à l’aide. […] C’est ainsi qu’à l’époque, nous avons dénoncé ces situations de fait. C’est ainsi que le président de la République est débarqué directement sur bout et a pris des engagements pour essayer d’accompagner la population en vue de les venir en aide et de secours.” (“But even though the majority of the community had rushed, they organized themselves to try to come to the aid while the central government could make decisions and send teams to help. […] This is how, at the time, we denounced these de facto situations. This is how the President of the Republic landed directly on the spot and made commitments to try to support the population in order to come to their aid and relief.”).

We therefore returned once again on that day, adding his personal version of the story to the others we had already collected, and we asked him who sounded the alarm and how the fishermen organized themselves for support:

“C’est la tradition au niveau de la communauté. À chaque fois qu’il y a des accidents pareils, ou à chaque fois qu’il y a une pirogue qui est partie en pêche et qui est disparue, si on reste autant de jours sans aucune nouvelle, la communauté s’organise pour aller le chercher pour venir en aide. Là, c’est une tradition. […] Le temps que l’administration centrale puisse dépêcher la marine pour faire la recherche. La communauté, la plupart du temps, dans ces situations pareilles, n’attend pas l’état central. On essaie de s’organiser au niveau local, pour essayer de venir en aide aux membres de la communauté qui sont en difficulté, en situation de pêche à plus forte durée. […] C’est ce qui prenait les pirogues pour essayer de rejoindre l’Europe, parce que cette pirogue contenait plus de 150 personnes.” (“It’s a tradition at the community level. Whenever there are accidents like this, or whenever a canoe goes fishing and disappears, if we go so many days without any news, the community organizes itself to go and find it and provide assistance. That’s a tradition. […] Until the central administration can dispatch the navy to search. The community, most of the time, in these situations like this, doesn’t wait for the central government. We try to organize ourselves at the local level, to try to help members of the community who are in difficulty, in fishing situations of longer duration. […] That’s what the canoes took to try to reach Europe, because this canoe contained more than 150 people.”)

Who were they?

“Vous voyez de tout, il y avait des pêcheurs, il y avait des gens qui venaient de l’intérieur du pays, parce qu’en fait, à l’intérieur du pays, il n’y a que l’agriculture, il n’y a plus assez de pluie, il n’y a plus l’accompagnement que l’état faisait avec les agriculteurs dans le monde rural. Et du coup, toutes les populations en milieu rural font l’exode vers les grandes villes et essayent de prendre les pirogues pour rejoindre l’Europe et al.ler travailler. […] Et également il y avait des femmes, il y avait des jeunes filles, parce qu’en fait, elles n’ont plus de mari, parce qu’en fait les jeunes ne trouvent plus de travail, ne gagnent plus leur vie correctement, donc ils ne peuvent pas se donner, donc de prendre des femmes. Et du coup, même les jeunes filles aussi, commencent véritablement à prendre les pirogues pour essayer de rejoindre l’Europe, pour aller travailler, comme les garçons. Tout à fait, tout à fait.” (“You see, everything. There were fishermen, there were people who came from the interior of the country, because in fact, in the interior of the country, there’s only agriculture, there’s no longer enough rain, there’s no longer the support the state used to provide to farmers in rural areas. And as a result, all the rural populations are exodusing to the big cities and trying to take canoes to reach Europe and go to work. […] And there were also women, there were young girls, because in fact, they no longer have husbands, because in fact, young people can no longer find work, no longer earn a decent living, so they can’t give of themselves, so they can’t take wives. And as a result, even young girls are really starting to take canoes to try to reach Europe, to go to work, like the boys. Absolutely, absolutely.”).

And, among these, who were those who have been rescued and those who drowned and perished?

“Il y avait au niveau de Mbour beaucoup de pertes en vie humaine, parce qu’en fait, les autres quartiers, les quartiers périphériques de Mbour, ces gens-là, ce ne sont pas des pêcheurs. Donc il y a un quartier typiquement pêcheur, qui est réservé aux pêcheurs, c’est le quartier Thiocé-Ouest. C’est habité par des pêcheurs. Mais les autres quartiers environnants, eux, ce ne sont pas des pêcheurs. Mais c’est pour cela que la majorité des rescapés de ces pirogues, c’est des pêcheurs. Parce qu’ils savaient nager, ils pouvaient tenir sous l’eau pendant au moins une heure, deux heures de temps, le temps que les secours viennent, pour leur venir en aide. […] Mais nous avons eu énormément de difficultés par rapport à cette situation de fait. Parce que dans une situation de catastrophe, parce que c’était une catastrophe, 150 personnes naufragées, les assistés demandent véritablement des gens qui ont des formations requises en ce sens. Et 24 heures, 48 heures après, il ne restait que des cadavres. On ne sortait que des cadavres. Donc, vous imaginez les situations que nous vivions.” (“There was a lot of loss of life in Mbour, because in fact, the other neighborhoods, the outlying neighborhoods of Mbour, those people are not fishermen. So there is a typically fishing neighborhood, which is reserved for fishermen, the Thiocé-Ouest neighborhood. It is inhabited by fishermen. But the other surrounding neighborhoods are not of fishermen. But that’s why the majority of survivors from these canoes are fishermen. Because they knew how to swim, they could stay underwater for at least an hour, two hours, until rescuers arrived to help them. […] But we had enormous difficulties with this situation. Because in a disaster situation, because it was a disaster, 150 people shipwrecked, those receiving assistance really ask for people who have the necessary training in this regard. And 24 h, 48 h later, there were only corpses left. We were only bringing out corpses. So, you can imagine the situations we were experiencing.”)

While talking with Mouhamadou, a friend of his, also a fisherman who directly participated in rescue operations, joined and showed us some pictures he took that day. He confirms Mouhamadou’s version, adding that, since the day of the shipwreck, he still recalls the image of people who emerged from their homes and went down to the beach, hoping not to find their loved ones among the dead recovered from the water. Once on land, the bodies were loaded into cars to be buried immediately. “Cependant, de nombreuses victimes n’ont pas été identifiées et personne ne connaît le bilan exact.”

To say that nobody knows the shipwreck’s “toll” or cost means that nobody can utter a clear and final word about the event, the dead, and the missing. This is arguably the dark side and the main shadow in that tragic and public story: a shipwreck with several witnesses and spectators but without a clear “toll”, a word of finality. Since the dark side is the one that remains open, the one impossible to close, it is therefore the space for ghosts [44], for those missing who are unidentified and uncounted, thus exceeding any toll and preventing the story from being passed on.

Looking at the pictures, Mouhamadou comments, “Quand ils sont morts, ils sont morts. Vous pouvez faire votre deuil et clore l’histoire. S’ils ont disparu, c’est plus difficile car tout reste ouvert”. (“When they’re dead, they’re dead. You can grieve and close the story. If they’re gone, it’s harder because everything remains open.) Jospehine, who joined us that day at the Maison de la Ville in Mbour from Joal, adds, “Toutes nos familles ont encore de l’espoir. Il est passè à de nombreuses reprises que des personnes ne donnent pas de nouvelles pendant une longue période et puis, soudainement, elles réapparaissent.” (“All our families still have hope. There have been many times when people go unanswered for a long time, and then suddenly reappear.”)

To leave the door open to hope and possibility seems to be a common attitude, a way to counter fatalism, perhaps representing its other face. Yet, accepting the truth, even in terms of fatalism (the will of God), has nothing to do with resignation, and it instead demands a clear definition of the “toll”—a measure of the size and the burden of this truth—in order to close it and start or continue to grieve. The fact is that, though differently, in each of these tragic stories, too many things remain open, too many dark numbers, facts, and figures preventing closure.

Three months after the shipwreck, Mouhamadou claims, there remains no real and effective rescue program or system:

“Les pêcheurs font ce qu’ils peuvent avec plus de 150 personnes à l’eau. Les pompiers n’ont pas les compétences ni le matériel nécessaire. Nous sommes sur la côte, dans l’un des principaux ports de pêche du pays ainsi que l’une des destinations touristiques internationales les plus populaires, mais il n’y a pas de système capable.” (“The fishermen did what they could with more than 150 people in the water. The firefighters lack the necessary skills and equipment. We are on the coast, in one of the main country’s fishing port and one of the most popular international tourist destinations, but there isn’t any effective system.”)

He continues, enlarging the picture: “L’Europe est venue piller nos côtes. De la concession de pêche avec l’UE, l’État devait obtenir 10 milliards, seulement 6 sont arrivés. Finalement, le gouvernement a maintenant tout bloqué, espérons que c’est sérieux […] Mais il faut considerer quand-meme la diminution des ressources halieutiques côtières et la nécessité d’aller plus loin pour soutenir l’économie familiale […] Avant, les pêcheurs n’avaient pas besoin de l’État, ils allaient bien. Le capitaine (Issa’s father) avait organisé un voyage réussi 4 ans plus tôt…ils ont de la famille en Europe, mais cette foi là il voulait partir lui-même aussi”. (“Europe came to plunder our coasts. From the fishing concession with the EU, the State was supposed to get 10 billion, only 6 arrived. Finally, the government has now blocked everything, let’s hope it’s serious […] But we must still consider the decline in coastal fishing resources and the need to go further to support the family economy […] Before, the fishermen didn’t need the State, they were doing well. That captain (Issa’s father) had organized a successful crossing 4 years ago… they have family in Europe, but this time he wanted to leave himself too.”)

Then he adds a further element that sheds a different light on those who embarked on the pirogue that day: “Plusieurs étaient malades, le capitaine lui-même était diabétique. Ils voulaient allér en Espagne pour se faire soigner. […] Au lieu de campagnes de sensibilisation aux risques, la mise en place d’un système de santé publique et d’un système de retraite aurait certainement un effet plus important sur la propension à migrer. Bien sûr, ce sont des interventions qui coûtent plus cher que la projection de films et l’organisation d’ateliers sur les risques dans les villages du Sénégal pour dissuader la migration. […] Mais si vous demandez aux jeunes de ne pas prendre les pirogues, il faut leur proposer des alternatives.” (“Several people were sick, the captain himself was diabetic. They wanted to go to Spain for treatment. […] Instead of risk awareness campaigns, establishing a public health system and a pension system would certainly have a greater impact on the propensity to migrate. Of course, these are interventions that cost more than showing films and organizing workshops on risks in Senegalese villages to deter migration. […] But if you ask young people not to take the canoes, you have to offer them alternatives.”)

The lack of a rescue system, the crisis of traditional fishing, the absence of social and health care: these too are facts, part of the shipwreck “toll”, and they speak of neither resignation nor fatalism.

10. Solidarity Matters

In previous work, we tried to explore solidarity on the border from a different standpoint: rather than conceiving of it as an ontological property of the subjects involved, we envisaged it as a matter of circulating energy among different actors differently situated. Beyond any conventional opposition between donors and recipients, our idea was based on the assumption of a specific positional, and not necessarily altruistic, proximity [30]. This is what we have called a materialistic approach to border crossing and transgression, with the intention of exceeding any binary opposition between political and humanitarian forms of solidarity. We thus suggest conceiving of it at both the community level and at large, that is, by looking for practices and forms that are autonomously organized by the subjects and that are involved in multiple sites, scales, and forms of relations, overcoming conventional political meanings. To this enlarged view on solidarity, it must be added that sometimes solidarity at the community level may reveal itself to be ineffective, and only affective or “intimate” [45,46]. In other words, it is not (only) a utilitarian or utilitaristic matter, and this is particularly true in (sadly frequent) cases of failure. As for the shipwreck in Mbour and for the cases of missing pirogues in Joal, it is possible to detect a specific form of solidarity among the neighbors in terms of both material support and affective participation in the personal grief of the families. Yet such a solidarity does not express itself in a humanitarian attitude, nor in explicit political claims against border policies. It just emphasizes the proximity of all the different people involved in building up that specific social reality that is a “family pirogue”. This could reflect a peculiar form of passive acceptance, a sort of fatalism, as the very lack of resentment against the “smugglers” among the survivors and the victims’ relatives may suggest. Yet there is another way to interpret such a lack of resentment without any passive or fatalistic interpretation. It could even reflect a form of implicit collective responsibility (“we are all smuggled, we are all smugglers”), as well as a claim of a broader common condition surpassing any kind of distinction, so as to stress the reality that they are all on the same boat or pirogue. If so, resentment stands on the opposite side, as a kind of state hostility against any form of freedom of movement.

11. Conclusions: Potential Deserters

After the shipwreck on September the 8th, all the national press agencies and many international media emphasized the enormous risks inherent in these hazardous journeys, labeled under the category of “illegal migrations”. Voaafrique, among others, reported that “Senegalese President Bassirou Diomaye Faye visited the site in Mbour on Wednesday. […] From the Atlantic coast, the president deplored a “human tragedy that is upsetting us all. […] The nation is in mourning,” he added, describing the situation as “particularly unbearable.” […] And he affirmed that the State would conduct a “relentless hunt” for the smugglers who transport migrants to Europe. Among the concrete measures announced, the president mentioned the establishment of a hotline to denounce traffickers.” (See https://www.voaafrique.com/a/le-pr%C3%A9sident-s%C3%A9n%C3%A9galais-diomaye-faye-promet-une-traque-sans-r%C3%A9pit-du-trafic-de-migrants/7781354.html. accessed on 1 February 2025)

We do not know whether the “numero vert” will be used or instead deserted by the people. Those who were asked did not clearly answer, oscillating between hopeful, suspicious, unwilling, or indifferent reactions. Yet, Mr. Faye himself knows that “illegal migration” is not only the outcome of trafficking and “passeurs”, insofar as stories like that of the shipwreck in front of Mbour testify to a general social and even physical proximity among alleged “traffickers and trafficked” and to a far broader and deeper will to flee that seems to be stronger than any dissuasive institutional effort. Behind the very idea of “potential migrants” is an actual everyday demand that, rather than being prompted by an organized network of traffickers, is a direct response to the lack of viable alternatives allowing individuals both a right to maintain material rights and possibilities in the country and a right to legal forms of emigration through visas. Moreover, it seems harsh, reductive, and superficial to conceive of Issa’s father and his family as a gang of smugglers. On the contrary, they are part of a broader and shared community marked by an overall and chronic crisis and are materially united by complex forms of cooperation and a sense of proximity.

At the same time, it is necessary to reckon with how an increasing sentiment of hostility and resentment is projected at the institutional level against any form or experience of migration, not only from Senegal, to Western countries, to the point where it is conceived of as a specific national betrayal. This hostility is in turn fueled by a growing nationalistic ethos infusing many African states, currently proactively involved and directly participating in efforts to counter any attempt at movement and mobility beyond African territories. Anyone who seeks to move beyond this contradictory “panafrican” and nationalist horizon [47] runs the risk of being labeled as a potential deserter of the Nation. It would be interesting to know how Issa, Awa, and Marie, as well as Claire and Mouhamadou, would respond to such an accusation.

Ethnography is always an open-ended matter. Conclusions are almost impossible, unless they do not add further questions and new possible concepts. In this case, the allusive term “potential deserter” ends up translating the official narrative, based on the right to stay, into its real injunctive significance, interpreted as a duty to stay. If states prohibit “potential migrants” from unauthorized migration within the context of a “war”, such a “war” is legitimized by a duty to stay in one’s own country, and everyone who does not follow the order is implicitly considered a traitor or a deserter.

Here, it is possible to uncover an implicit answer to the questions posed at the beginning of our contribution. Actually, the ongoing recourse to fishermen’s pirogues directly testifies to a will to escape that neither the rhetoric of voluntary return and potential migrants nor the emphasis on the right to stay is able to counter. Thus, rather than evil or aliens, smugglers and organizers are perceived as they are, that is, as part of an overall community mainly made of fishermen and shipowners who, for different reasons (sea grabbing, industrial fishing, climate change, and sea pollution) are forced to consider their pirogues more as a means of transport than as a fixed asset for the traditional economy. When introducing our work, we started with a further general question concerning the kind of social relations, family ties, solidarities, and mutual aid involved in the organization of an unauthorized journey, as well as the perceptions of and reactions to the necropolitical effect of border enforcement and to loss and grief. A (partial) answer in this case would be more representative, and it stems from a classical quotation and a certain refrain echoed in Senegal.

There exists a famous passage from Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura, one on which, among others, Hans Blumenberg had worked for a long time, particularly in a book whose title, “Shipwreck with Spectator” [48], seems to somewhat depict the tragedy that occurred in Mbour at the beginning of September 2024:

“Pleasant it is, when on the great sea the winds trouble the waters, to gaze from shore upon another’s great tribulation: not because any man’s troubles are a delectable joy, but because to perceive what ills you are free from yourself is pleasant.”(Lucr. II, 1–14)

With these words, indeed, Lucretius emphasizes how witnessing the “great tribulation” of others from afar provides a pleasant sensation, whose reason lies not in enjoying their danger but in appreciating the distance that guarantees oneself adequate safety. If it is true that distance is the very condition that makes safety possible, all the stories collected here do not seem to provide an analogous sense of distance, nor of safety. On the contrary, they bear witness to a fundamental proximity, that is, to the deep bonds and interweavings that unite all the people involved, in all their different positions and destinies, in that shipwreck.

In Senegal, it is common to say “on est ensemble”, not only to stress a fundamental or contingent agreement among people, a unity of intentions, but also, and more literally, to signal the reality of being in the same position and condition or, if you want, “on the same boat”. This could be true for all those who died in the shipwreck in front of Mbour; for those who have been recognized and buried in a graveyard; for the bodies without names buried anonymously on the beaches; for the names of those who disappeared without bodies; and for the invisible passengers without a name or a body who were onboard that day and whose presence/absence remains totally obscure, unknown. Additionally, it is true for those who disappeared with the missing pirogue, fostering the hopes of their beloved and forcing them into an open yet empty and lonely waiting time. It is also true for the survivors, the shipowner, his son, his family, the neighbors, and the whole neighborhood. More generally, it is true for all the witnesses and spectators, and for a whole society that perfectly understands the reason why a pirogue, no longer just a means for fishing, may become a way to flee. In all its gradations and acceptations, this “ensemble” seems to abolish any possible distance at which one can watch a shipwreck while feeling safe, and this may sound like another name for the very idea of solidarity among a people of “potential migrants”, or deserters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.R. and L.Q.P.; Investigation, F.R. and L.Q.P.; Writing—original draft, F.R. and L.Q.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the SOLROUTES, an ERC project (EU grant n. 101053836—www.solroutes.eu—X: @solroutes). The views and opinions expressed in this essay, however, are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or of the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the funding body can be held responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Comitato Etico per la Ricerca di Ateneo (CERA) (protocol code: 2021.50 and date of approval: 4 August 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The research has been carried out thanks to the participation of Jose Gonzalez Morandi, a film maker in SOLROUTES project, and Babacar Ndiaye, a Senegalese activist for the freedom of movement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Laczko, F.; Tjaden, J.; Auer, D. Measuring Global Migration Potential, 2010–2015, Briefing Series, No. 9; International Organization for Migration Global Migration Data Analysis Centre: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden, J.; Auer, D.; Laczko, F. Linking migration intentions with flows: Evidence and potential use. Int. Migr. 2019, 57, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bah, T.L.; Batista, C. Understanding Willingness to Migrate Illegally: Evidence from a Lab in the Field Experiment. NOVAFRICA 2018. Available online: https://novafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/TijanBah_Understanding-willingness-to-migrate-illegally_Bah_Batista.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Deleuze, G. Postscript on the Societies of Control; Routledge: London, UK, 1992; Volume 59. [Google Scholar]

- IOM (International Organization for Migration). The Impact of Peer-to-Peer Communication on Potential Migrants in Senegal—Impact Evaluation Report; IOM: Geneve, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tandian, A. Profils de Sénégalais candidats à la migration: Des obsessions aux desillusions. Rev. Afr. Des Migr. Int. 2020, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Appiah-Nyamekye, J.; Selormey, E. African Migration: Who’s Thinking of Going Where? 2018. Available online: www.afrobarometer.org (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Kvietok, A.N. “Their Paths, Their Journeys: Transnational Mobility, Social Networks, and Coming Back Home amongst Senegalese Returnees in Dakar, Senegal” (2018). Anthropology Honors Projects. 31. Available online: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/anth_honors/31 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Kushminder, K. Reintegrations Strategies: Conceptualizing How Return Migrants Reintegrate; Palgrave MacMillian: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- MMC, Mixed Migration Center. Return and Reintegration in the Context of Senegal; Working Paper; Mixed Migration Center: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Patuel, F. Une avalanche de financements pour des résultats mitigés. In Rapport D’étude-bilan Sur les Projets et Programmes Migratoires au Senegal de 2005–2019; Heinrich Boll Stiftung: Dakar, Senegal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bellagamba, A. Legacies of Slavery and Popular Traditions of Freedom in Southern Senegal (1860–1960). J. Glob. Slavery 2017, 2, 72–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.; Bellagamba, A.; Botta, E.; Ceesay, E.; Cissokho, D.; Engeler, M.; Lenoël, A.; Oelgemöller, C.; Riccio, B.; Sakho, P.; et al. Migration drivers and migration choice: Interrogating responses to migration and development: Interventions in West Africa. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2022, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cissokho, D.; Riccio, B.; Sakho, P.; Zingari, G.N. Migchoice Country Report: Senegal, University of Birmingham. 2021. Available online: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/documents/college-social-sciences/government-society/research/migchoice/22136-migchoice-country-report-–-aw-accessible.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).