Confirmatory Factors Analysis of Multicultural Leadership of Youth in the Three Southern Border Provinces of Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.1.1. Definition of Leadership

2.1.2. Meaning of Multicultural Society

2.1.3. Youth Leadership: A Core Construct in Multicultural Development Contexts

2.1.4. Components of Multicultural Leadership

2.1.5. Theoretical Framework for Multicultural Leadership in Youth

- Awareness and acceptance of cultural diversity. The cornerstone of multicultural leadership lies in the capacity to recognize, accept, and value cultural diversity. This component finds theoretical resonance in Berry’s Acculturation Framework [13], which posits that successful navigation of multicultural environments necessitates a strategy of integration, wherein individuals maintain their cultural identity while engaging with other groups. Banks [1] further underscores this through his multicultural education theory, advocating for culturally responsive pedagogy that nurtures critical consciousness and cultural pluralism. Uygur [20] links mindfulness to intercultural sensitivity, suggesting that awareness and non-judgmental attention to cultural differences significantly reduce ethnocentrism. Moreover, Tip et al. [40] highlight the role of threat perception in attitudes toward multiculturalism, asserting that educational interventions can mitigate perceived cultural threats. Van de Vijver and Breugelmans [62] validate the construct of multiculturalism through empirical methods, confirming that openness to diversity is associated with psychological adaptability and lower intergroup anxiety.

- Intercultural communication skills. Effective intercultural communication is a linchpin in reducing cultural misunderstandings and enhancing social cohesion. Theoretical support for this component is grounded in Giles’ Communication Accommodation Theory [22], which explains how individuals adjust their communication styles to minimize social distance. Ippolito [35] and Halualani [36] emphasize the practical complexities of intercultural communication within academic institutions, providing evidence that fostering dialogic engagement among culturally diverse youth enhances mutual respect. Cherkowski and Ragoonaden [50] propose that intercultural communication competence should be a core element of professional development, particularly in multicultural educational settings. Berger [63] offers a meta-theoretical analysis of interpersonal communication, asserting that adaptive communication behaviors are critical in multicultural contexts. These insights suggest that intercultural communication is linguistic and involves nuanced behavioral, emotional, and cognitive adaptability.

- Flexibility and adaptability in multicultural contexts. Navigating the uncertainties of multicultural settings requires flexibility and cognitive adaptability. This component aligns with Boski’s [54] model of cultural adaptation, which conceptualizes intercultural adjustment as a dynamic interplay of acculturation strategies and situational demands. Masten and Cicchetti [23] contribute through the concept of developmental resilience, emphasizing that adaptive capacities are fostered through exposure to and recovery from stressors. Uhl-Bien et al. [14] extend this view through Complexity Leadership Theory, positing that adaptive leadership is essential in contexts characterized by nonlinearity and cultural fluidity. Sopa and Tuksino [53] validate a measurement model for adaptability in Thai educational contexts, suggesting that cognitive and emotional regulation skills are foundational for youth leadership in diverse environments.

- Creative problem solving in multicultural contexts. Creative problem solving represents a higher-order cognitive function necessary for conflict resolution and innovation in multicultural societies. Lederach [24] introduces the concept of “moral imagination” in peacebuilding, which entails envisioning alternatives to violence rooted in empathy and inclusivity. Fisher, Ury, and Patton [64], through their Principled Negotiation Model, advocate for win–win solutions that respect cultural differences. Xu et al. [55] present meta-analytic evidence that collaborative problem solving significantly enhances critical thinking, particularly in intercultural learning environments. Webb et al. [17] assert that equitable dialogue and group-based decision making foster inclusive problem solving. These theoretical insights underline that effective leadership in multicultural contexts must be grounded in collaborative, empathetic, and culturally sensitive problem–resolution strategies.

- Building intercultural collaboration networks. Intercultural networks serve as the scaffolding for sustained multicultural engagement. Putnam’s Social Capital Theory [12] offers a foundational perspective, distinguishing between bonding and bridging social capital. Bridging capital, in particular, fosters intergroup trust and cooperation. Freeman [57], via Stakeholder Theory, underscores the importance of inclusive engagement in sustaining collaborative initiatives. Greenleaf [46] and his Servant Leadership Model advocate for relational leadership that prioritizes community wellbeing. Ang’ana and Kilika [65] provide empirical evidence from Kenyan organizational settings, demonstrating how collaborative leadership nurtures durable cross-functional networks. Junhasobhaga et al. [56] emphasize the importance of inclusive, intergenerational networks in multicultural Thai communities, reinforcing the argument for strategic partnership building.

- Developing culturally relevant morality and ethics. Morality and ethics, when contextualized within cultural traditions, become potent tools for peacebuilding. Kohlberg [66] provides a structural approach to moral development, while MacIntyre [25] champions virtue ethics, stressing the role of community in moral formation. Noddings [61], through her ethics of care, shifts the focus to relational and empathetic moral reasoning, which is particularly salient in multicultural leadership. Aquino and Reed [67] articulate the concept of moral identity, asserting that individuals who internalize moral values are more likely to engage in prosocial behavior. Hembasat and Pimpasalee [60] explore moral indoctrination within Thai contexts, advocating for a value-based education model. Thanman [59] links ethical development with national strategies in the digital era, suggesting that culturally grounded ethics are crucial for navigating contemporary societal challenges.

2.2. Sample

2.2.1. Sampling Design and Recruitment Process

2.2.2. Potential Systematic Biases and Limitations

- Gatekeeper bias. Because participant recruitment relied on local authorities and institutions, there is a possibility of gatekeeper bias, whereby only the most visible, cooperative, or institutionally recognized youth leaders were selected. Marginalized or dissenting youth leaders—such as those unaffiliated with formal groups or holding critical perspectives—may have been underrepresented.

- Selection bias due to administrative filtering. Local officials and community representatives may have exercised subjective judgment in identifying participants who reflected positively on their institutions or were perceived as “model youth.” This could lead to social desirability bias, where more politically neutral or compliant youth are overrepresented, potentially excluding those involved in activism or countercultural initiatives.

- Urban–rural imbalance. Although rural and semi-urban areas were included, it is possible that urban youth (especially from district centers) had a disproportionately higher representation, owing to better access to communication channels and more formalized youth leadership structures. This may affect the generalizability of the findings to remote rural youth, who often face different challenges and have fewer leadership development opportunities.

- Religious and ethnic homogeneity within zones. Despite efforts to ensure ethnic and religious diversity across the three provinces, homogeneity within some sub-districts could have skewed the responses. For example, a sub-district with a high concentration of Malay Muslim youth may exhibit leadership patterns specific to that cultural context, which may not generalize across groups.

- Voluntary participation and self-selection bias. Participation in the survey was voluntary, introducing the possibility of self-selection bias. Youth leaders with stronger motivation, confidence, or prior exposure to leadership training may have been more inclined to participate, leading to an overrepresentation of more engaged individuals.

2.2.3. Implications for Generalizability

2.3. Research Instruments

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Expanded Profile of the Sample Group

- Age distribution. Participants were aged between 15 and 24 years, corresponding to the definition of “youth” as articulated by the United Nations [71] and commonly used in Southeast Asian policy contexts [72]. The majority (approximately 62%) fell within the 18–21 age range, reflecting their engagement in post-secondary education or early professional activities. This age group is particularly significant, as it represents a developmental stage marked by identity formation, value consolidation, and increased civic engagement.

- Gender composition. The sample included a relatively balanced gender distribution, as follows: 52% female, 47% male, and 1% non-binary or chose not to disclose. This balanced representation ensures that leadership dynamics are not skewed by gender bias and allows for meaningful exploration of how leadership traits manifest across different gender identities, particularly within culturally conservative settings.

- Ethnic background. The three southern border provinces are ethnically diverse, and the sample reflected this plurality, as follows: 60% identified as Malay Thai, 30% identified as Thai Buddhist, and 10% belonged to other minority groups, including Chinese Thai, Khmer, or Thai Muslim individuals from outside the Deep South. The presence of multiple ethnic groups within the sample supports the investigation into how multicultural leadership operates in pluralistic and potentially sensitive environments. Ethnic background was a relevant variable in shaping intercultural communication preferences and adaptability to diverse leadership scenarios.

- Religious affiliation. Religious affiliation was reported as follows: 58% Muslim, 38% Buddhist, and 4% Christian or other religions. Given the sociopolitical history of the southern provinces—particularly the identity-based tensions between Buddhist and Muslim communities—this religious breakdown reflects the real-world challenges youth leaders must navigate to foster intercultural cooperation and peacebuilding.

- Socioeconomic background. Participants represented a spectrum of socioeconomic statuses, classified using parental occupation, household income, and access to education, as follows: 45% came from low-income households, typically engaged in agriculture, fisheries, or informal labor sectors; 40% were from lower–middle-income families, often involved in small-scale commerce or public service; 15% identified with middle- or upper-middle-income levels, generally with access to tertiary education and broader social capital. These socioeconomic distinctions are essential for interpreting youth leadership potential, as previous research has established correlations between social capital, access to resources, and leadership development.

- Educational status. Most participants were either currently enrolled in educational institutions or recent graduates, as follows: 68% were attending high school or vocational school, 25% were enrolled in universities or teacher training colleges, and 7% were working youth leaders engaged in community organizations or local administrative bodies. Their educational environments often served as key incubators for leadership skills, particularly in community development, public speaking, and intercultural engagement.

3.2. Analysis of Descriptive Statistics for Multicultural Leadership Among Youth in the Three Southern Border Provinces

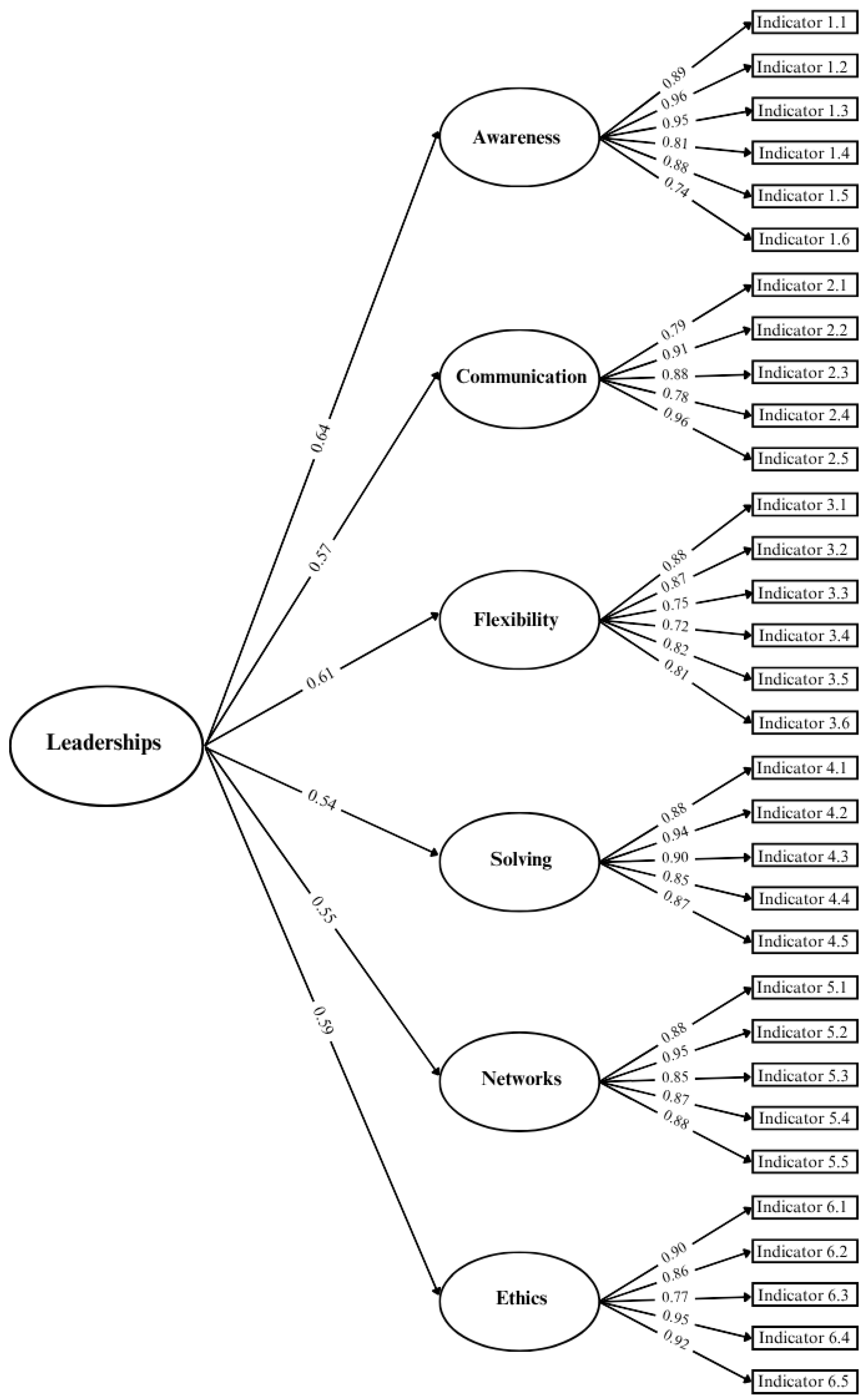

3.3. Results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Youth Multicultural Leadership in the Three Southern Border Provinces

4. Discussion

- Component 1: Awareness and acceptance of cultural diversity. Awareness and acceptance of diversity emerged as a fundamental component of multicultural leadership, as the foundation for fostering understanding and coexistence in multicultural societies. This is particularly relevant to the three southern border provinces of Thailand, which exhibit significant ethnic, religious, linguistic, and cultural diversity. While this diversity presents opportunities for social harmony, it also poses challenges in promoting peace and reconciliation. The findings align with previous research suggesting that recognizing and understanding differences in cultural dimensions, beliefs, and ways of life can mitigate conflict and enhance peaceful coexistence [41,73]. Encouraging youth to embrace and appreciate cultural diversity is essential for reducing bias and prejudice, which contribute to social divisions. This, in turn, plays a pivotal role in fostering long-term peace within diverse communities. Moreover, awareness and acceptance of cultural diversity serve as critical tools for promoting intercultural learning and fostering mutual understanding. Encouraging an open-minded perspective, self-reflection, and the reduction in egocentric biases enables individuals to perceive others as equals. The concept of cultural humility is particularly significant, as it facilitates the development of positive relationships and minimizes barriers arising from cultural differences. A key approach to cultivating multicultural leadership involves participatory learning processes, such as providing youth with opportunities for direct interactions with diverse groups and promoting cultural appreciation. By engaging in these experiences, youth develop inclusive attitudes and recognize the value of cultural diversity [21,74]. Additionally, fostering open-minded attitudes toward cultural differences is crucial for reducing intergroup conflict and ensuring sustainable social harmony. Research indicates that mindfulness-based interventions and the development of cultural sensitivity are effective strategies for reducing biases in intercultural interactions. A non-judgmental mindset further promotes intercultural understanding and conflict resolution, reinforcing the principles of multicultural leadership [9,20]. To enhance awareness and acceptance of diversity, youth should be equipped with the skills necessary to navigate complex cultural landscapes, fostering peace and mutual understanding in regions characterized by sustainable cultural diversity [41,75].

- Component 2: Intercultural communication skills. Cross-cultural communication skills constitute a crucial component of multicultural leadership, as they facilitate mutual understanding and help mitigate misunderstandings in culturally diverse societies. In the context of Thailand’s three southern border provinces, where ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity is prominent, the development of effective cross-cultural communication skills can foster harmonious relationships, reduce social tensions, and promote intercultural understanding. Theoretical perspectives emphasize the importance of creating inclusive spaces for dialogue, adaptation, and relationship building in culturally diverse settings. Transparent communication and mutual understanding are fundamental pillars for social cohesion, as effective communication can be a powerful tool for resolving conflicts, fostering trust, and strengthening intergroup relationships [52]. In multicultural societies, trust and mutual respect are critical in interpersonal communication, particularly in relationships between youth from diverse cultural backgrounds [51,63]. Adapting communication strategies to align with cultural norms and expectations can significantly reduce tensions and foster positive interactions. Furthermore, electronic and interpersonal communication skills are instrumental in cultivating a deeper understanding of cultural diversity [22,42]. Leaders in multicultural environments must develop the ability to adapt their communication styles to engage effectively across cultural boundaries. Strategies such as organizing intercultural activities, providing platforms for youth from different cultural backgrounds to collaborate, and encouraging critical reflection on cultural beliefs and values can enhance intercultural competencies among young leaders [48,50].

- Component 3: Flexibility and adaptability in multicultural contexts. Flexibility and adaptability are essential for youth navigating multicultural environments, particularly in the three southern border provinces of Thailand, where cultural and religious diversity is deeply embedded in social structures. The ability to adapt effectively enables young individuals to address challenges creatively, manage social changes, and coexist harmoniously within diverse communities. Research suggests that youth must be cognitively flexible when processing new information and adjusting to culturally diverse contexts, allowing for peaceful cohabitation within society. Adaptability involves the capacity to modify behaviors and thought processes in response to evolving circumstances, employing critical reasoning and positive analytical skills to navigate intercultural interactions. These capabilities equip youth with the resilience to overcome challenges, adjust to unfamiliar environments, and engage meaningfully in multicultural settings [23,53]. Cultural adaptation plays a pivotal role in fostering social harmony within diverse societies. Youth should be encouraged to develop an appreciation for cultural and religious diversity, embracing differences in traditions, customs, and ways of life. By actively engaging in cultural exchange and dialogue, young individuals can cultivate sustainable mental and social balance in diverse social settings [13,54]. Leaders who demonstrate adaptive capabilities can motivate and inspire others to embrace social change and intercultural coexistence. Additionally, youth with adaptability skills can play a vital role in facilitating community resilience, particularly in challenging or unpredictable situations, such as community conflicts or crisis management [14,15,76]. In the 21st century, resilience and adaptability have become critical competencies, enabling youth to navigate rapid societal transformations effectively. These skills are indispensable in coping with crises and recovering from adversities, ultimately fostering self-confidence and leadership capacity in dynamic and uncertain environments [77].

- Component 4: Creative problem solving in multicultural contexts. Creative problem solving in multicultural contexts is a critical skill that enhances cooperation, mitigates conflict, and fosters trust in culturally diverse regions, such as Thailand’s three southern border provinces. Given the ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity in this area, effective problem solving requires in-depth analysis, creative thinking, and structured processes that ensure the equal participation of all stakeholders. In a multicultural context, problem solving should prioritize group dynamics and social relationships, emphasizing collective well-being over individual interests. Individuals should perceive themselves as integral members of a community, ensuring that decision-making processes consider the broader impact on the group while promoting unity and social harmony. Implementing group-based interactions with continuous and sustainable communication can help reduce misunderstandings, increase cooperation, and foster constructive intergroup relationships [11,17]. Constructive conflict resolution is fundamental for trust building and cooperation in diverse communities. An inclusive negotiation process—where all parties have an equal opportunity to express their opinions—helps reduce tensions and facilitates open dialogue. Collaborative problem solving through idea exchange, discussion, and reflection is crucial in multicultural settings [24,55]. Adopting negotiation strategies that prioritize mutual benefits enhances the sense of acceptance and satisfaction among stakeholders, thereby minimizing conflict and fostering long-term peace. Furthermore, critical thinking skills, teamwork, and emotional regulation in culturally diverse environments are a foundational element for effective collaboration and conflict resolution. These skills enable individuals to navigate cultural differences with empathy and diplomacy, ensuring more effective problem-solving outcomes [64,78].

- Component 5: Building intercultural collaboration networks. Building intercultural networks is fundamental to fostering positive relationships, reducing conflict, and cultivating a society based on mutual trust. This is particularly crucial in Thailand’s three southern border provinces, where ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity necessitates proactive efforts to strengthen social cohesion. When youth leaders develop the ability to collaborate with individuals from diverse backgrounds, they contribute to peacebuilding, reduce misunderstandings, and create strong, cooperative relationships across communities. Encouraging youth leaders to engage with civil society organizations and other relevant stakeholders is instrumental in fostering mutual trust and sustainable regional development. Research suggests that promoting participation in diverse social activities enhances trust building and mitigates prejudices between cultural groups, which is essential for effective, creative, and self-sustaining community networks [12,56]. Youth leaders who establish strong connections with key societal actors—such as community leaders, religious organizations, and civil society groups—gain increased support for initiatives that advance interfaith understanding and regional peace [56,57]. Developing networking skills is essential for leading youth-driven initiatives, particularly those focused on sustainable development and peacebuilding. Additionally, fostering intercultural relationships within communities requires promoting understanding and acceptance of cultural and religious diversity. Youth leaders should actively facilitate projects that encourage dialogue, collaboration, and knowledge sharing across cultural boundaries [58,79]. To ensure the sustainability of cross-cultural collaboration, youth leaders should establish inclusive networks that integrate all relevant sectors, linking youth groups, local communities, government organizations, and other key stakeholders. Leadership training programs should be designed to equip youth with the necessary skills to drive these networks effectively. Moreover, incorporating cultural and religious principles as foundational elements in network development can foster greater awareness, mutual understanding, and long-term peace in multicultural societies [15,58].

- Component 6: Developing culturally relevant morality and ethics. The development of morality and ethics, closely linked to cultural values, is a fundamental factor in fostering a peaceful and sustainable society in the three southern border provinces of Thailand. Given the region’s religious and ethnic diversity, youth leaders should be instilled with moral principles derived from religious teachings and local traditions to promote social harmony and mitigate conflicts. Cross-cultural learning fosters an understanding of and respect for differences, enabling peaceful coexistence. Therefore, ethical leadership development is essential, enabling youth to serve as role models and guide their communities in a constructive direction. Encouraging participation in public welfare activities and volunteerism helps reduce inappropriate behaviors, while fostering a sense of social responsibility. The application of the sufficiency economy philosophy further enables youth to cultivate a balanced lifestyle, develop self-reliance, and recognize the broader societal implications of their actions. This aligns with the notion that morality forms the foundation of ethical behavior, particularly in societies facing cultural diversity and social challenges. When youth internalize moral values, such as honesty, compassion, and respect for differences, they contribute to conflict reduction and foster mutual understanding among ethnic and religious groups [25]. Moral development is an intellectual process that enables individuals to apply reason in ethical decision making—an essential skill for youth leaders. Rational consideration of the societal impact of their actions empowers youth leaders to adopt constructive approaches rather than responding with violence or prejudice. Additionally, moral education should be integrated into the sufficiency economy philosophy, which is a guiding principle for balancing material and spiritual well-being in Thai society [59,79]. Compassion and empathy are central to promoting morality in society. These values can be applied in multicultural contexts by encouraging youth to engage in altruistic activities, such as volunteering, community service, and peace advocacy. Such engagements foster a supportive society and reduce conflicts stemming from cultural misunderstandings [60,61]. Establishing an ethical identity is a crucial determinant in motivating individuals to choose virtuous actions. Encouraging youth leaders to recognize their societal roles and responsibilities—such as participating in peace-promoting activities, collaborating with religious organizations, and producing media content that challenges cultural biases—contributes to the development of a sustainable ethical identity [68]. Furthermore, youth leaders should embody humility and prioritize collective well-being over personal interests. By acting as cultural mediators and organizing activities that foster intergroup understanding, they can bridge cultural divides and promote long-term social cohesion [46].

- Alignment with and extension of multicultural leadership theories. The study’s findings are well-aligned with foundational models of multicultural leadership, such as Banks’ theory of multicultural education [1] and Berry’s acculturation framework [13]. Banks emphasizes the cultivation of multicultural competencies through education to prepare individuals for democratic citizenship in diverse societies. In parallel, Berry’s model identifies integration—marked by high cultural maintenance and high participation in the host society—as the most adaptive acculturation strategy. The empirical dominance of “awareness and acceptance of diversity” in the factor structure strongly supports these theoretical positions, suggesting that the development of youth leadership must begin with cultivating open-mindedness and cognitive empathy [1,13]. However, this study extends these theories by empirically demonstrating that ethical grounding—represented by “developing culturally relevant morality and ethics”—plays an equally foundational role in youth leadership. While moral development has been historically treated as peripheral in some multicultural frameworks, the present study’s results resonate with MacIntyre’s [25] virtue ethics and Noddings’ [61] ethics of care, both of which argue that moral character and empathy are central to responsible leadership.

- Convergence with youth leadership development theories. The empirical structure derived from this study shares conceptual similarities with transformational leadership theory [15], particularly regarding the emphasis on adaptability, vision, and ethics. Components such as flexibility and adaptability in multicultural contexts and creative problem solving reflect the transformational traits of intellectual stimulation and individualized consideration. Moreover, servant leadership theory, especially as articulated by Greenleaf [46] and extended by Eva et al. [33], is echoed in the study’s emphasis on building networks and promoting moral leadership. Notably, the integration of social capital theory [12] into the leadership model—via the “intercultural collaboration networks” component—provides a critical link between leadership development and community-level cohesion. This suggests a shift from hierarchical leadership models toward relational and networked forms of influence, consistent with Uhl-Bien’s complexity leadership theory [14].

- Divergence from traditional youth leadership models. Traditional youth leadership theories have often prioritized traits, such as assertiveness, goal orientation, and authority assertion [44]. These models, while relevant in more homogeneous or organizational contexts, are increasingly criticized for their lack of cultural nuance. The present study diverges from these models by foregrounding intercultural competence, adaptability, and ethical sensitivity—competencies often neglected in classical frameworks. This divergence suggests that traditional paradigms of youth leadership may be inadequate in culturally complex and conflict-sensitive settings. Instead, the study supports a contextualist approach to leadership, which emphasizes that effective leadership must be culturally embedded, context-responsive, and morally attuned [2,34].

- Relevance to peacebuilding and social cohesion theories. The research also intersects meaningfully with peacebuilding frameworks, particularly Lederach’s [24] moral imagination theory, which posits that leaders must develop the capacity to “wage peace” through empathy, creativity, and ethical commitment. The empirical support for components, such as creative problem solving and culturally grounded ethics, positions youth leaders as administrative figures and as agents of social transformation, capable of mending social fractures and fostering inclusive coexistence. Moreover, the study’s findings align with Galtung’s [80] distinction between “positive peace” and “negative peace,” with multicultural leadership functioning as a tool for cultivating the former through grassroots engagement and inclusive dialogue.

- Implications for theorizing youth leadership in post-conflict societies. In post-conflict or ethno-religiously fragmented contexts such as southern Thailand, youth leadership must be reconceptualized beyond the scope of organizational efficiency or individual charisma. The current study suggests a developmental–communitarian framework, wherein leadership is simultaneously a personal competency and a collective resource. This reconceptualization mirrors the constructivist peace education perspective [81], which argues that leadership should be nurtured through dialogic, participatory, and experiential learning processes that promote empathy and social justice.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Banks, J.A. Cultural Diversity and Education: Foundations, Curriculum, and Teaching; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arasaratnam, L.A. Multiculturalism, Beyond Ethnocultural Diversity and Contestations. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2013, 37, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeheem, K. Causal Relationships between Religious Factors and Ethical Behavior among Youth in the Three Southern Border Provinces of Thailand. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 108, 104626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmann, A. Ethno-religious Conflict in Southern Thailand: The Dynamics of Insurgency. In Routledge Handbook of Religion and Politics; Jerryson, M., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 324–336. [Google Scholar]

- International Crisis Group (ICG). Southern Thailand: Moving towards Political Solutions? 2009. Available online: https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/thailand/southern-thailand-moving-towards-political-solutions (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Zenn, J. Xinjiang and China’s Rise in Central Asia: A Security Perspective. In Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism in China: Domestic and Foreign Policy Dimensions; Clarke, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Youth as Agents of Peacebuilding in Conflict Zones; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kaosaiyaphon, O. The Virtual Social Network for Educational Development in Multicultural Society. J. Educ. Stud. Silpakorn Univ. 2012, 10, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Patanapichai, P.; Tantinakhongul, A.; Saleemad, K.; Yoonisil, W. A Study of Attributes of Multicultural Leadership in Student Teachers in Three Southern Border Provinces. J. Res. Curric. Dev. 2021, 11, 158–166. [Google Scholar]

- Agbai, E.; Agbai, E.; Oko-Jaja, E.S. Bridging Culture, Nurturing Diversity: Cultural Exchange and Its Impact on Global Understanding. Res. J. Human. Cult. Stud. 2024, 10, 42–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation: A Conceptual Overview. In Cultural Psychology: Contemporary Themes and Perspectives; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Marion, R.; McKelvey, B. Complexity Leadership Theory: Shifting Leadership from the Industrial Age to the Knowledge Era. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Riggio, R.E. Transformational Leadership; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold, A.; Amigo, M. The Stage of Multicultural Leadership: Challenges and Opportunities Which Leaders are Facing Nowadays; Linnaeus University: Linnaeus, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, N.M.; Ing, M.; Burnheimer, E.; Johnson, N.C.; Franke, M.L.; Zimmerman, J. Is There a Right Way? Productive Patterns of Interaction during Collaborative Problem Solving. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geda, A.; Tesfaye, F.A. An Assessment of Educational Leaders’ Multicultural Competences in Ethiopian Public Universities. Eur. Sci. J. 2016, 12, 387–402. [Google Scholar]

- Bunkrong, D. Analysis of the Education Management Approach with Driving Education to Thailand 4.0. Asian J. Arts Cult. 2018, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Uygur, S.S. A Look at Intercultural Sensitivity from the Perspective of Mindfulness and Acceptance of Diversity. J. Educ. Gift. Young Sci. 2022, 10, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirivichayaporn, U.; Srisuantang, S.; Tanpichai, P. Factors Affecting to the Cultural Awareness of Undergraduate Students, Kasetsart University Kamphaeng Sean Campus. Veridian E-J. Silpakorn Univ. 2018, 11, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, H. Communication Accommodation Theory: Negotiating Personal Relationships and Social Identities Across Contexts; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.; Cicchetti, D. Resilience in Development: Progress and Transformation. In Developmental Psychopathology; Cicchetti, D., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 271–333. [Google Scholar]

- Lederach, J.P. The Moral Imagination: The Art and Soul of Building Peace; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, A. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory; University of Notre Dame Press: Notre Dame, IN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Praphaiphet, S.; Kundaeng, S.; Loetvathong, R.; Praphaiphet, S. Leadership: Concepts, Theories, and Elements. J. Intellect Educ. 2023, 2, 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Suphawittayacharoenkun, N. Leadership of School Administrators under Sakon Nakhon Primary Educational Service Area Office 1. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Sakon Nakhon Rajabhat University, Sakon Nakhon, Thailand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wongkrueason, P. Development Model of Teacher Leadership on Instructional Management in Thailand 4.0 Era in Primary Schools under the Regional Education Office No. 11. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Sakon Nakhon Rajabhat University, Sakon Nakhon, Thailand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chanta, C. A Study of Academic Leadership of School Administrators under Office of Basic Education in Nakhon Phanom Province. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Sakon Nakhon Rajabhat University, Sakon Nakhon, Thailand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Seeda, W. The Relationship Between Transformational Leadership and Personnel Management of School Administrators Under the Office of Sakon Nakhon Primary Educational Service Area 3. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Sakon Nakhon Rajabhat University, Sakon Nakhon, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ang’ana, G.A.; Chiroma, J. Collaborative Leadership and Its Influence in Building and Sustaining Successful Cross-Functional Relationships in Organizations in Kenya. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 23, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Impeng, A. Transformational Leadership of School Administrators Affecting the Effectiveness of Teachers’ Performance in Schools Under Nakhon Phanom Primary Educational Service Area Office 2. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Sakon Nakhon Rajabhat University, Sakon Nakhon, Thailand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Eva, N.; Robin, M.; Sendjaya, S.; van Dierendonck, D.; Liden, R.C. Servant Leadership: A Systematic Review and Call for Future Research. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Velsor, E.; McCauley, C.D.; Ruderman, M.N. The Center for Creative Leadership Handbook of Leadership Development, 3rd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ippolito, K. Promoting Intercultural Learning in a Multicultural University: Ideals and Realities. Teach. High. Educ. 2007, 12, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halualani, R.T. Interactant-Based Definitions of Intercultural Interaction at a Multicultural University. Howard J. Commun. 2010, 21, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thitadhammo, P.M.; Pangthrap, K.; Kamol, P. Living Together of Peoples in Multicultural Societies of Thailand: A Case Study of Multicultural Society of Muang District, Chiang Mai Province. Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya Univ. J. 2019, 6, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Parekh, B. Rethinking Multiculturalism: Cultural Diversity and Political Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalk-Soekar, S.R.G.; Van de Vijver, F.J.R.; Hoogsteder, M. Attitudes toward Multiculturalism of Immigrants and Majority Members in the Netherlands. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2004, 28, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tip, L.K.; Zagefka, H.; Gonzalez, R.; Brown, R.; Cinnirella, M.; Na, X. In Support of Multiculturalism Threatened by…Threat Itself? Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2012, 36, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udompittayason, W.; Chamama, N.; Lorga, T.; Khianpo, R. Cultural Humility: Learning for Understanding the Cultural Health Practices of Clients. J. Boromarajonani Coll. Nurs. 2019, 6, 202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Leelasrisiri, C. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Leadership Skills for Students at Private Vocational Institutions in Thailand. Payap Univ. J. 2015, 5, 433–439. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil, C.A. Bridging Generations: Applying “Adult” Leadership Theories to Youth Leadership Development. New Dir. Youth Dev. 2006, 109, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzes, J.M.; Posner, B.Z. The Leadership Challenge; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Camino, L.; Zeldin, S. From Periphery to Center: Pathways for Youth Civic Engagement in the Day-to-Day Life of Communities. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2002, 6, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, R.K. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness; Paulist Press: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- van Linden, J.A.; Fertman, C.I. Youth Leadership: A Guide to Understanding Leadership Development in Adolescents; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, S.; Rockstuhl, T.; Tan, M.L. Cultural Intelligence and Competencies. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 5, pp. 433–439. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, M.A.; Barnett, R.V.; Lesmeister, M.K. Enhancing Youth Leadership through Experiential Learning. J. Ext. 2007, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cherkowski, S.; Ragoonaden, K. Leadership for Diversity: Intercultural Communication Competence as Professional Development. Teach. Learn. Prof. Dev. 2016, 1, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Boroditsky, L. How Language Shapes Thought: The Linguistic Relativity Theory Revisited. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2011, 71, 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Corchia, L. The Uses of Mead in Habermas’ Social Theory: Before the Theory of Communication Action. Ital. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 9, 209–234. [Google Scholar]

- Sopa, P.; Tuksino, P. Construct Validity Testing of Flexibility and Adaptability Measurement Model of Mathayom Suksa Three Students under Khon Kaen Primary Educational Service Area Office 5. MBU Educ. J. Fac. Educ. Mahamakut Buddh. Univ. 2017, 8, 146–158. [Google Scholar]

- Boski, P. Cultural Psychology and Acculturation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, E.; Wang, W.; Wang, Q. The Effectiveness of Collaborative Problem Solving in Promoting Students’ Critical Thinking: A Meta-Analysis Based on Empirical Literature. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junhasobhaga, J.; Pongsung, K.; Yokinmisjinja, C.; Sanont, R. The Cooperative Network Development in Multicultural Society of New Generation Leaders to Sustainable Learning Community. Acad. J. Bangkokthonburi Univ. 2020, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dhirabhaddo, P.; Phoowachanathipong, K.; Vi, P.; Prapassornpitaya, M.; Sarisee, N. Development of a Collaboration Network for Promoting Creative Spaces with Social Cultural Capital through Three Generations. Buddh. Psychol. 2024, 9, 659–676. [Google Scholar]

- Thanman, S. Morality Strengthening in 21st Century, for Organization of Digital Economy. Valaya Alongkorn Rev. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2019, 9, 146–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hembasat, P.; Pimpasalee, W. Morality and Ethics Indoctrination Guidelines in Thai Society. J. Public Admin. Politics 2020, 9, 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings, N. Caring: A Relational Approach to Ethics and Moral Education, 3rd ed.; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vijver, F.J.R.; Breugelmans, S.M.; Schalk-Soekar, S.R.G. Multiculturalism: Construct Validity and Stability. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2008, 32, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, C.R. Interpersonal Communication: Theoretical Perspectives and Future Directions. J. Commun. 2005, 55, 415–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.; Ury, W.; Patton, B. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ang’ana, G.A.; Kilika, J.M. Collaborative Leadership in an Organizational Context: A Research Agenda. J. Hum. Resour. Leadersh. 2022, 6, 48–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L. The Philosophy of Moral Development: Moral Stages and the Idea of Justice; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Aquino, K.; Reed, A. The Self-Importance of Moral Identity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1423–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Center of Deep South Watch. The Data and Trends of the Situation Severity in the South; Center of Deep South Watch: Pattani, Thailand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Laeheem, K. Causal Factors Contributing to Youth Cyberbullying in the Deep South of Thailand. Children 2024, 11, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Youth Report: Youth and Migration; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ASEAN. ASEAN Youth Development Index 2020; ASEAN Secretariat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira dos Santos, M.T. Diversity and Acceptance: Views of Children and Youngsters. In ISEC2010—Inclusive and Supportive Education Congress; Queen’s University Belfast: Belfast, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Emami, A.; Safipour, J. Constructing a Questionnaire for Assessment of Awareness and Acceptance of Diversity in Healthcare Institutions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekasuk, P. Living Multiculturally in a Multi-linguistic Organization: A Case Study of MAP Foundation. J. Public Admin. Politics 2017, 6, 57–98. [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen, E.I. Complexity Leadership Theory and the Leaders of Transdisciplinary Science. Inform. Sci. 2018, 21, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanpheng, S.; Meechan, S.; Langka, W. Development of the Resilience Scale for Upper Secondary Students. J. Educ. Res. Srinakharinwirot Univ. 2023, 18, 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Pollastri, A.R.; Epstein, L.D.; Heath, G.H.; Ablon, J.S. The Collaborative Problem-Solving Approach: Outcomes across Settings. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 188–199. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, D.; Cameron, A. Collaborative Leadership: Building Relationships, Handling Conflict and Sharing Control; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Galtung, J. Violence, Peace, and Peace Research. J. Peace Res. 1969, 6, 167–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, M. Critical Peace Education. In Peace Education and Human Rights; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 135–154. [Google Scholar]

| Index | Criteria | After Adjusting Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Interpretation | ||

| p value | p > 0.05 | 0.07 | Excellent fit |

| χ2/df | ≤3.00 | 1.11 | Excellent fit |

| CFI | ≥0.95 | 0.99 | Excellent fit |

| GFI | ≥0.90 | 0.96 | Excellent fit |

| AGFI | ≥0.90 | 0.94 | Excellent fit |

| TLI | ≥0.95 | 0.99 | Excellent fit |

| RMSEA | ≤0.06 | 0.01 | Excellent fit |

| SRMR | ≤0.08 | 0.03 | Excellent fit |

| Variables | Component Weight | t | R2 | Component Score Coefficient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | ||||

| First order factor analysis | |||||

| Component 1: Awareness and acceptance of cultural diversity | |||||

| Indicator 1.1 | 0.89 | -- | -- | 0.16 | 0.03 |

| Indicator 1.2 | 0.96 | 0.12 | 7.69 | 0.14 | 0.01 |

| Indicator 1.3 | 0.95 | 0.13 | 7.64 | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| Indicator 1.4 | 0.81 | 0.13 | 8.45 | 0.19 | 0.06 |

| Indicator 1.5 | 0.88 | 0.13 | 8.22 | 0.18 | 0.04 |

| Indicator 1.6 | 0.74 | 0.13 | 8.52 | 0.20 | 0.07 |

| Component 2: Intercultural communication skills | |||||

| Indicator 2.1 | 0.79 | -- | -- | 0.15 | 0.01 |

| Indicator 2.2 | 0.91 | 0.13 | 6.82 | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| Indicator 2.3 | 0.88 | 0.12 | 7.20 | 0.12 | 0.02 |

| Indicator 2.4 | 0.78 | 0.13 | 6.05 | 0.09 | 0.03 |

| Indicator 2.5 | 0.96 | 0.14 | 7.04 | 0.14 | 0.02 |

| Component 3: Flexibility and adaptability in multicultural contexts | |||||

| Indicator 3.1 | 0.88 | -- | -- | 0.20 | 0.06 |

| Indicator 3.2 | 0.87 | 0.12 | 7.22 | 0.15 | 0.03 |

| Indicator 3.3 | 0.75 | 0.13 | 8.06 | 0.21 | 0.04 |

| Indicator 3.4 | 0.72 | 0.11 | 6.40 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| Indicator 3.5 | 0.82 | 0.12 | 6.95 | 0.13 | 0.02 |

| Indicator 3.6 | 0.81 | 0.12 | 6.88 | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| Component 4: Creative problem solving in multicultural contexts | |||||

| Indicator 4.1 | 0.88 | -- | -- | 0.16 | 0.04 |

| Indicator 4.2 | 0.94 | 0.15 | 7.38 | 0.19 | 0.03 |

| Indicator 4.3 | 0.90 | 0.14 | 7.02 | 0.16 | 0.03 |

| Indicator 4.4 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 7.27 | 0.18 | 0.05 |

| Indicator 4.5 | 0.87 | 0.14 | 7.16 | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| Component 5: Building Intercultural collaboration Networks | |||||

| Indicator 5.1 | 0.88 | -- | -- | 0.14 | 0.01 |

| Indicator 5.2 | 0.95 | 0.15 | 7.06 | 0.15 | 0.01 |

| Indicator 5.3 | 0.85 | 0.14 | 6.15 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| Indicator 5.4 | 0.87 | 0.14 | 6.20 | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| Indicator 5.5 | 0.88 | 0.15 | 7.46 | 0.17 | 0.02 |

| Component 6: Developing culturally relevant morality and ethics | |||||

| Indicator 6.1 | 0.90 | 0.16 | 0.02 | ||

| Indicator 6.2 | 0.86 | 0.13 | 6.76 | 0.12 | 0.01 |

| Indicator 6.3 | 0.77 | 0.12 | 6.25 | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| Indicator 6.4 | 0.95 | 0.13 | 7.15 | 0.15 | 0.03 |

| Indicator 6.5 | 0.92 | 0.13 | 7.23 | 0.15 | 0.01 |

| Second order factor analysis | |||||

| Component 1 (Aware) | 0.64 | 0.06 | 11.02 | 0.86 | -- |

| Component 2 (Commu) | 0.57 | 0.06 | 9.76 | 0.81 | -- |

| Component 3 (Flexibi) | 0.61 | 0.06 | 10.45 | 0.75 | -- |

| Component 4 (Solving) | 0.54 | 0.06 | 9.44 | 0.72 | -- |

| Component 5 (Network) | 0.55 | 0.06 | 9.32 | 0.83 | -- |

| Component 6 (Ethics) | 0.59 | 0.06 | 10.09 | 0.76 | -- |

| Chi-square = 411.81 | df = 370 | p = 0.066 | |||

| GFI = 0.96 | AGFI = 0.94 | RMR = 0.047 | RMSEA = 0.013 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laeheem, K.; Tepsing, P.; Hayisa-e, K. Confirmatory Factors Analysis of Multicultural Leadership of Youth in the Three Southern Border Provinces of Thailand. Societies 2025, 15, 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070202

Laeheem K, Tepsing P, Hayisa-e K. Confirmatory Factors Analysis of Multicultural Leadership of Youth in the Three Southern Border Provinces of Thailand. Societies. 2025; 15(7):202. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070202

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaeheem, Kasetchai, Punya Tepsing, and Khaled Hayisa-e. 2025. "Confirmatory Factors Analysis of Multicultural Leadership of Youth in the Three Southern Border Provinces of Thailand" Societies 15, no. 7: 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070202

APA StyleLaeheem, K., Tepsing, P., & Hayisa-e, K. (2025). Confirmatory Factors Analysis of Multicultural Leadership of Youth in the Three Southern Border Provinces of Thailand. Societies, 15(7), 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070202