Abstract

This article explores the role of the European Union (EU) as a normative gender actor promoting women’s participation in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) within the Eastern Partnership (EaP) region. In a context marked by global inequality and overlapping international efforts, this paper assesses the extent to which EU-driven Europeanisation influences national gender policies in non-EU states. Using a postfunctionalist lens, this research draws on a qualitative analysis of EU-funded programmes, strategic documents, and a detailed case study encompassing Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine, Belarus, and Azerbaijan. This study highlights both the opportunities created by EU initiatives such as Horizon Europe, Erasmus+, and regional programmes like EU4Digital and the challenges presented by political resistance, institutional inertia, and socio-cultural norms. The findings reveal that although EU interventions have fostered significant progress, structural barriers and limited national commitment hinder the long-term sustainability of gender equality in STEM. Moreover, the withdrawal of other global actors increases pressure on the EU to maintain leadership in this area. This paper concludes that without stronger national alignment and global cooperation, EU gender policies risk becoming symbolic rather than transformative.

1. Introduction

Gender inequality in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) remains a major challenge in global education and employment. Despite progress in recent decades, women remain under-represented in STEM fields, especially in leadership roles. Gender equality is increasingly seen as not only a matter of social justice but also a key factor in sustainable development. Various global actors, including international organisations like the United Nations (UN) or national governments such as Canada or the United States through its U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) have made substantial efforts to address these disparities. However, the European Union (EU) stands out through its unique approach, integrating gender equality into both its internal policies and external relations, using its normative power to influence neighbouring countries and other global regions.

The EU is founded on a core set of norms and values that it consistently integrates into all its actions. As this paper will further demonstrate, gender equality is one of the cornerstone values promoted by the EU, both inside and outside of its borders, and as pointed out by multiple studies, gender-balanced representation across economic, social and political spheres leads to sustainable growth and development [1,2,3,4,5]. In terms of identity, the EU positioned itself “at the forefront of the protection and fulfilment of girls’ and women’s rights”, both within the EU and in “developing, enlargement and neighbourhood countries”, its contributions leading to the inclusion of gender issues at the centre of the UN Sustainable Development Goals Agenda [6]. The EU can therefore be seen as trying to assert itself as a global gender actor that propagates its values even beyond its borders.

Development is a field particularly affected by gender issues, yet these are often overlooked. There is not enough talk about how gender ties into development studies, especially considering that in order to achieve social development, half of a given population cannot be left on the sidelines. When it comes to a just and sustainable transition for industries, women must have a role to play too. One way of empowering them to take this role is by encouraging their participation in STEM. According to the Deputy Head of the Delegation of the European Union to the United Nations, Hedda Samson, “gender inequality is pervasive (…) Despite girls and young women making up the majority of science graduates at bachelor’s and master’s levels, a significant gap emerges as they progress in their academic careers” [7].

This paper assesses the effectiveness of EU efforts in Eastern Partnership (EaP) countries, focusing on EU-funded Education and Research Initiatives, as an illustration of Europeanisation in action, particularly by encouraging women’s participation in STEM fields —a sector critical for innovation, economic competitiveness, and sustainability [8]. Therefore, our research question refers to what extent EU-driven Europeanisation fosters the integration of gender equality in STEM policies and practices across EaP countries. While the global landscape includes various actors promoting gender equality, this article acknowledges that recent shifts in international cooperation—such as reductions in support for gender-focused initiatives by some major global donors—have undermined overall policy coherence, and it primarily focuses on the EU’s external action and by analysing EU-funded programmes, institutional frameworks, and local socio-political dynamics, aiming to identify both the opportunities and limitations of EU influence, as well as its growing responsibility in supporting global gender equality in the STEM sector.

The analysis reveals that, while the EU has successfully supported efforts to increase women’s participation in STEM, persistent structural barriers remain. Achieving gender parity in STEM is not just a matter of equality but also a crucial driver for social development, as diverse and inclusive scientific communities contribute to more innovative and equitable solutions for global challenges. Ensuring the long-term sustainability and impact of EU’s gender policies will require stronger partnerships, tailored strategies, and continuous engagement with local stakeholders.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Hypothesis and Theoretical Framework

Previous studies indicate that the EU’s normative power and the process of Europeanisation are key factors for advancing gender equality beyond its borders [9,10]. The EU has effectively promoted gender equality through initiatives such as the Gender Action Plan III (GAP III), incorporating gender perspectives into research funding programmes like Horizon Europe and Erasmus+ [11,12].

This study examines how the European Union’s external Europeanisation process affects gender equality in STEM, particularly within EaP countries. The following hypothesis guides the analysis:

Hypothesis:

The effectiveness of EU-driven Europeanisation in promoting gender equality in STEM is shaped by political, socio-economic, and cultural barriers in EaP countries, potentially limiting the uptake and sustainability of such measures.

To ensure analytical consistency, we introduce in this study a unified evaluative framework comprising three dimensions: (1) the degree of policy uptake, measured by the integration of gender equality measures into national STEM strategies; (2) institutional embedding, reflected in the establishment or reinforcement of mechanisms such as Gender Equality Plans (GEPs) or dedicated departments; and (3) long-term sustainability, assessed by whether actions continue beyond EU funding or are incorporated into national budgets and priorities. In this context, “effectiveness” refers to the extent to which EU-driven initiatives lead to measurable structural or institutional changes in partner countries, while “sustainability” captures the durability and ownership of these changes beyond the duration of EU support.

To explore these dynamics, this research adopts qualitative methods: (1) a document analysis of EU-funded programmes focused on STEM education and gender mainstreaming in EaP countries, (2) a content analysis of strategic statements by EU actors, and (3) a case study evaluating selected initiatives that aim to enhance women’s participation in STEM. The analysis identifies key barriers and facilitators influencing implementation.

To better understand how Europeanisation unfolds beyond EU borders—especially in sensitive areas such as gender equality—we employ a postfunctionalist approach that offers valuable insights. This perspective emphasises that norm transfer is rarely a top-down or purely technical process. Instead, it is shaped by domestic politics, public opinion, and identity dynamics, which either facilitate or impede the internalisation of EU values [13,14,15]. In the STEM education and research context, promoting gender equality touches on deeper cultural narratives about gender roles, merit, and modernity. Consequently, local responses to EU initiatives often mirror broader societal debates about identity and sovereignty, rather than merely technical capacity. Ultimately, postfunctionalism also highlights the importance of local agency and democratic context in shaping the outcomes of EU engagement. In the context of gender equality in STEM, it encourages us to go beyond policy instruments and consider how values are negotiated, adapted, or resisted in everyday academic, institutional, and political life.

2.2. Operationalising Europeanisation in the EaP Context

Although traditionally associated with the EU’s internal integration and policy alignment processes, Europeanisation has increasingly extended its influence to neighbouring non-member states. In the EaP context, the term refers to the diffusion of EU-originated norms, practices, and institutional templates across this looser network of bilateral and multilateral cooperation. Rather than pursuing full alignment with EU acquis, this form of Europeanisation depends on strategic alignment, soft power incentives, and shared interests to promote reforms, particularly in areas like education, governance, and gender. While there is no single, universally accepted definition of Europeanisation, most interpretations view it as a driver of change—both formal and informal—in third countries. This process often involves elements such as policy transfer, normative persuasion, and the gradual adoption of governance models. In EaP countries, Europeanisation focuses less on legal harmonisation and more on shaping societal values and institutional priorities via funding mechanisms, political dialogue, and civil society engagement. The EU’s gender mainstreaming agenda exemplifies an area where Europeanisation functions both symbolically and practically [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

In the STEM field, the EU’s influence materialises primarily through educational programmes, research cooperation, and visibility for under-represented groups such as women. The promotion of gender equality in STEM is not imposed but encouraged through funding conditionalities and thematic priorities embedded in initiatives like Erasmus+, Horizon Europe, and EU4Digital. As these programmes are locally adopted, as we will argue, they often reflect varying degrees of commitment depending on national contexts, making Europeanisation in this area uneven and heavily reliant on local institutional capacity and political will, and gender equality in STEM thus becomes a test for how effectively the EU can promote progressive values through non-binding but strategically significant instruments of external influence.

The diffusion of EU norms and practices to third countries, such as those in the Eastern Partnership, occurs unevenly, through a combination of mechanisms that reflect different degrees of intentionality and institutional engagement. In the context of gender equality in STEM, these mechanisms range from direct influence—such as attaching conditions to funding programmes—to subtler forms, like inspiring local reforms through the visibility of EU success stories or participation in multilateral projects [19].

Conditionality remains one of the clearest tools, whereby the EU ties access to resources to certain commitments—such as the inclusion of gender equality plans in universities. Another mechanism is socialisation, whereby local actors engage with EU institutions, values, and discourses, through academic exchanges or collaborative projects. In contrast, indirect mechanisms, such as externalisation and imitation, reflect more voluntary forms of alignment, as domestic stakeholders adopt EU norms either to improve legitimacy or access opportunities [19,24].

These transmission modes are not mutually exclusive. In practice, they coexist and interact depending on the policy area, the strength of EU engagement, and the receptiveness of the local political environment. In the case of gender equality in STEM, the EU’s influence is typically stronger where national strategies already support reform and weaker in contexts dominated by traditional or patriarchal norms.

3. Results

This section presents the main findings of this research, with a focus on EU-funded initiatives that aimed to promote gender equality in STEM in the EaP countries. We analyse how these programmes were implemented, their impact on institutions and civil society, and the limitations encountered in the process of external Europeanisation. Using the evaluative framework outlined above, the results presented in the following case study will be analysed along three axes: (a) the alignment of national STEM and gender policies with EU frameworks; (b) institutional capacity-building measures; and (c) the sustainability of reforms. This approach enables a comparative assessment of the extent to which EU-funded initiatives generate transformative, rather than symbolic, changes in EaP countries, highlighting both achievements and persistent challenges in advancing women’s participation in STEM.

3.1. Case Study: EU-Funded STEM Education and Research Initiatives in EaP Countries

3.1.1. Overview of EU–EaP Cooperation in STEM

In this section, we examine how EU-funded initiatives and projects have supported research institutions and universities in EaP countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine) in fostering women’s participation in STEM. We will assess both the successes and challenges of these initiatives and their role in the external Europeanisation of gender equality norms.

The EaP was launched in 2009 and represents the specific Eastern facet of the Neighbourhood Policy. At the beginning, all the regional partners were excited about the initiative, especially due to incentives that became progressively more enticing, such as the association agreements and the advantageous trade deals provided, as well as the potential for visa liberalisation, which was granted to the Republic of Moldova in 2014 and to Georgia and Ukraine in 2017 [25].

However, relations between the EU and Eastern partners deteriorated, particularly with Belarus and Georgia. In 2021, Belarus officially suspended the country’s participation in the Eastern Partnership but, instead of completely severing ties with the country and its people, the EU decided to repurpose its programmes and financial assistance away from governmental institutions and to rechannel them towards the people through CSOs, human rights groups, the independent media, education, culture, and small and medium-sized enterprises found in exile, the country still having access to some EU’s regional programmes EU 4 Gender Equality and Partnership for Good Governance through this groups [26]. In the case of Georgia, its EU accession process has been halted since 2024 also due to political instability and democratic backsliding [27].

As previously noted, fostering gender equality in higher education and research can be seen as an EU priority, especially in STEM fields. Although there are ongoing tensions in the interaction between the EU and some partner countries, efforts to promote EU values have continued even when the relation with national governments were completely severed as in the case of Belarus. This demonstrates the Union’s resilience in promoting a value-based agenda and the willingness of other societal segments to participate, e.g., educational intuitions and the civil society.

3.1.2. Country-Level Highlights

In Belarus, the EU granted EUR 300,000 for a project called “Women in Tech”, implemented between 2022 and 2023 by the Centre for Gender Studies from European Humanities University, a private Humanities and Liberal Arts Belarusian university found in Vilnius, Lithuania, after it was forcibly closed and made to relocate from Minsk by Belarusian authorities. The project targeted Belarusian women “from within the country and those who have been forced to migrate” with the purpose of kickstarting their careers in the IT sector or helping them further develop their competences and advance their careers if they were already active in the field. The project included a conference in Vilnius with almost 700 attendees, a free educational programme called “Login to Tech”, that covered “three months of training, 21 video lectures by IT experts on careers, opportunities and how to get into the industry, more than 50 homework assignments, tests and checklists, and personal reviews by professional recruiters”, IT workshops, a workshop on CV development, a study titled “Belarusians on the way to IT: myths, fears, obstacles”, summer camps and a mentoring programme [28,29]. The project was so successful that after the end of the implementation period, the EU continued to fund Women in Tech actions, such as the Vilnius Conference, which is now held annually.

The EU member states also play a role as individual actors in promoting gender values, such as in the case of Ukraine where the German government through its Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action has supported a wide range of initiatives aimed towards supporting women in the energy sector still located in Ukraine, as well as those displaced in Germany by the war. For this purpose, they decided to fund a series of projects in partnership with the Women Energy Club of a Ukraine non-governmental organisation (NGO), with their activity based on four pillars: reintegration into the Ukrainian labour market, integration in Germany, further professional qualification through capacity building and the improvement of professional skills, networking and mentoring activities [30].

In Georgia, similar patterns emerge in the involvement of NGOs and higher education institutions as catalysts for change, where a manual for gender equality action plans for higher education and research institutions was created in 2024 with the support of the government of Norway and the UN [31] and the launch of a mentorship programme for women in tech was implemented by the Business and Technology University from Tbilisi [32].

3.1.3. Gender Data and Statistical Gaps

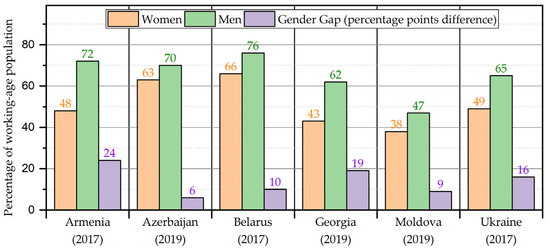

Some other clear initiatives financed by the EU that support this goal, even if indirectly, include the Statistics Through Eastern Partnership (STEP) programme, implemented throughout the 2019–2022 time period, with a cost of EUR 4.7 million, which represented the first regional statistics initiative in the Eastern Neighbourhood region. Among the 16 projects under STEP, there was also gender statistics, which focused on improving the availability of sex and gender related data in multiple fields while also highlighting the importance of accessible, high-quality data for establishing policy priorities and enabling national and regional comparisons to be made. One such finding was related to gender gaps in the labour market where women were found to be less likely to have a job or to seek one, compared to men, with the highest discrepancies being recorded in Armenia with a gender gap of 24%, while the lowest can be found in Azerbaijan with a 6% difference (see Figure 1) [33].

Figure 1.

Labour force participation rate, by sex, and gender GAP, EaP COUNTRIES, 2019. Source: [33].

One of the main causes of these gender gaps was identified as the unequal distribution of domestic work and child or adult caregiving responsibilities. According to the data, women spent on average 3.69 h more per day on those tasks than men did, 3.32 h in Azerbaijan, 2.37 h in Belarus and 2.28 h in Moldova, with additional notes that in Moldova, “six out of ten mothers spend two hours per day to wash, feed and dress their children, and only two out of ten fathers do similar activities for an hour a day” and “almost all (90%) women engage in cooking compared to only 44% of men” and that “men and boys have more free time than women and girls at all stages of life, from childhood through to older age” [33].

STEP supported partner countries in producing better statistics corresponding to European and international best practice standards and, as a result, they were able to use the aggregated data to support evidence-based policymaking while tackling lasting gaps in information and potential biases that institutions and people operationalised with, especially in terms of gender. Even though they received know-how in terms of conducting and disseminating high-quality statistics, methodological challenges still persist, making regional comparisons difficult to portray accurately.

According to the “Gender Equality and post-2020 Eastern Partnership Priorities: A Guide on How to Promote Gender Equality in Policy, Programming and Reform Work”, which was developed under the EU4Gender Equality Reform Helpdesk project, different Eastern partner countries tend to adapt internationally standardised methodologies to fit their national preferences, which gives rise to consistency issues and makes comparing data at the regional level all the more difficult. Two specific areas that were highlighted in this sense were the measurement of gender-based violence and the sampling of groups such as ‘ICT professionals’ that do not always correspond to the EU ones [34].

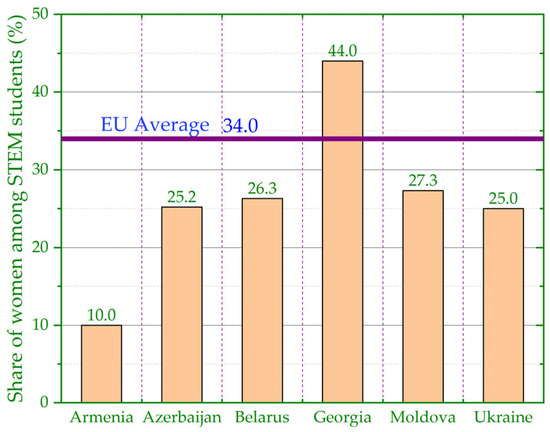

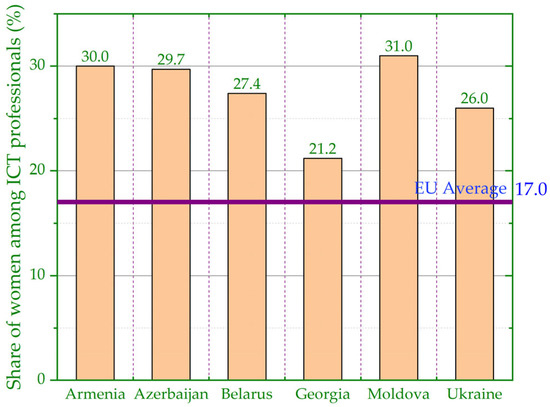

Women’s participation in STEM and ICT-related jobs specifically has been highlighted as a crucial element in achieving the key goal of resilient digital transformation as part of the EU’s digital strategy for sustainable growth. The main issues identified in achieving gender equality for fulfilling this goal in the six EaP countries were gaps in digital literacy, the significant under-representation of women among STEM students (26.3% on average, see Figure 2) and professionals (27.6% on average, see Figure 3), their limited representation in ICT businesses and decision-making on digital transformation, and online discrimination and cyber violence [34].

Figure 2.

Share of women among STEM students. Source: [34].

Figure 3.

Share of women among ICT professionals. Source: [34].

3.1.4. Socio-Cultural Norms and Gender Stereotypes

These issues are perpetuated by the societal context in the sense of the prevalence of stereotypes associated with gender roles. As such, one in three girls in Moldova and Georgia pointed towards the commonly held belief that STEM is not a domain suitable for girls as being among the reasons for their lack of interest in the field while the parental and teacher disapproval of aspirations to study ICT was also highlighted as a deterrent by girls in Moldova and Ukraine [34].

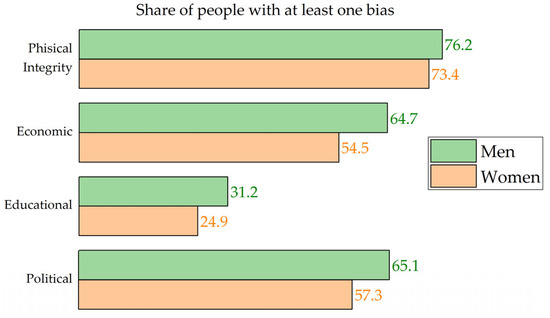

These findings are mirrored by the 2023 Gender Social Norms Index Report, which identified how widespread gender biases are globally. According to the data, nearly 90% of people hold at least one gender bias (as it can be seen in Figure 4) and biases are prevalent among both men and women and are found in countries with both low and high rankings on the Human Development Index, demonstrating how widespread these beliefs actually are [35].

Figure 4.

Biases in gender social norms are prevalent among both men and women. Note: Based on 80 countries and territories with data from wave 6 (2010–2014) or wave 7 (2017–2022) of the World Values Survey, accounting for 85 percent of the global population. Source: [35].

The EU addresses these issues through regional programmes such as EU4Digital, which aims to share the benefits of the EU’s Digital Single Market with the EaP countries by funding and implementing multiple projects that support a sustainable digital transformation. EU4Digital is currently in its Phase II (2022–2025) after a successful Phase I (2019–2022) that prompted the continuation of the project [36]. Among the projects implemented so far there is the project Connecting Research and Education Communities (EaPConnect), which ran in Phase 1 (2015–2020—EUR 13 million) and continues in Phase 2 (2020–2025—EUR 10 million) of the programme and works as a connecting line between research and education communities from the EU and five national research and education networks in the EaP (the Academic Scientific Research Computer Network of Armenia, the Institute of Information and Technology AzScienceNet in Azerbaijan, the Georgian Research and Educational Networking Association, the National Research and Educational Networking Association of Moldova and the User Association of Ukrainian Research and Academic Network) in order to reduce the digital divide [37].

Other important projects included in the programme are as follows: Cybersecurity East (all EaP countries, 2019–2022, EUR 3121,600), REDI: Rural Empowerment through Digital Inclusion (Georgia, 2023–2027, EUR 5.5 mil), EU4Security Moldova (the Republic of Moldova, 2024–2027, EUR 5.5 mil), DT4UA (Ukraine, 2022–2025, EUR 17.4 mil), Digital University—Open Ukrainian Initiative (Ukraine, 2023–2027, EUR 4.9 mil), CyberEast+ (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, the Republic of Moldova, Ukraine, 2024–2027, EUR 3.5 mil), etc.

A common feature of these programmes is their reliance on higher education institutions, CSOs and research centres to lead efforts toward promoting and implementing the actions necessary to achieve gender equality in the wider society in general and in STEM in particular.

Other EU-wide initiatives also benefit the EaP, such as the European Research Area through its actions towards achieving gender equality in research and innovation, the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions, which focus on doctoral and postdoctoral programmes, the Erasmus+ programme, and Horizon Europe. They are operating both inside and outside of the EU through collaborations between Member States, third countries and other relevant stakeholders.

Horizon Europe, for instance, introduced an eligibility criterion that forces research institutions to have a GEP if they want to receive funding through the programme and sets the integration of a gender dimension into the research submitted as a default requirement while also noting that, if during the evaluation process, multiple research teams have the same score, gender balance will be used as a tiebreaker. Additionally, Horizon also established a self-target of achieving gender parity in their boards, expert groups and evaluation committees, with 50% of them being women [38].

3.1.5. Migration and Diaspora as Norm Diffusion Channels

Beyond formal EU-funded actions, we also want to underline the importance that migration from the EaP region and the national diasporas have on the countries of origin. Although migration and diaspora dynamics are not part of the core institutional analysis, they represent a complementary channel through which EU gender norms—including those related to STEM—can indirectly reach EaP countries. First and foremost, emigration is a significant challenge in the EaP region, with a lot of people leaving in order to find better opportunities. Without properly engaging the diasporas, the skills and aptitudes that those people acquire abroad will not benefit the home country unless they choose to return. According to 2020–2021 data, 32.5% of the Armenian population (964,848 people) left Armenia, out of which 9.3% (89,387 people) are residing in the EU; 11.3% of Azerbaijani population (1,155,852 people) are living abroad, out of which 4% (45,034 people) are located in the EU; 21.4% of Georgians (852,816 people) left their country, out of which 19.7% (168,323) can be found in the EU; 13.6% of Ukrainians (5,901,067 people) have emigrated, out of which 20.8% (1,229,893) have remained in the EU (the data were collected before the war in Ukraine); in Moldova, 25.2% (1,013,417) of its population live abroad, while 46.8% (474,023) are residing in the EU [39]; and for the case of Belarus, 12% of Belarusians (1,480,794) have emigrated, out of which 16.6% (246,283) are in the EU [40]. This is illustrated in Figure 5, which maps diaspora structures and the extent to which they are formally engaged in national policies across EaP countries.

Figure 5.

The importance that migration from the EaP region and the national diasporas have on the countries of origin. Source: authors’ graph based on [40] data.

Secondly, despite the sizable number of people living abroad, the actual impact of diasporas on national policies varies significantly. As such, it is important to note that in Armenia, citizens residing outside of country cannot vote, and in terms of engaging their diaspora, the government created an Office of the High Commissioner for Diaspora Affairs and an Armenia-Diaspora Partnership Strategy, but they are focused strictly on creating a “state-centered, pro-state” diaspora and on “further deepening the ideology of statehood-building and state-centeredness” [41].

Regarding projects, the state engages the diaspora through iGorts, which allows Armenian specialists from the diaspora to collaborate with Armenia’s public administration for one year in order to “contribute to the research, improvement and the development of programmes and policies within state institutions” [42]. Over 250 Diaspora Armenian specialists have participated in the programme since its 2020 launch [43] and its success led to a voluntary version of the programme in 2024, which is currently ongoing, called the DiasPro Professional Volunteer Program where experts can work together with government institutions online and in person by offering them “professional consultations, experience sharing, training sessions, and other forms of expertise” [44,45].

In Azerbaijan, however, the country’s official migration management policy stipulates that the government should foster close ties with diaspora communities and associations and assist them in protecting their rights and interests abroad through the State Committee on Affairs with Diaspora. Even so, there are no skill sharing opportunities or any other means through which the Azerbaijani diaspora can contribute to governmental policies except for the Congress of World Azerbaijanis, which only meets every 5 years [46].

Georgia has enacted a law on Compatriots Residing Abroad and Diaspora Organisations, and it offers its citizens a platform created by the Diaspora Relations Department within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where it provides members from the Georgian diaspora from across countries with networking opportunities and it keeps them up to date with information on legislative and policy changes in the country [40].

Moldova showcases a well-developed network of diaspora-engaging complementary initiatives. The country has a National Diaspora Strategy covering 2015–2025 and a National Programme “Diaspora” covering 2024–2028, and it has operated the Diaspora Relations Bureau since 2012, which develops national policies in which the input of the diaspora is asked for. The Bureau has its own subset of projects and initiatives, among which is the most notable, the Diaspora Engagement Hub, which grants governmental funding for projects implemented by officially registered associations and educational centres [47]. There is also the Diaspora Connect platform funded by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation where any individual citizen can post and interact with the community [48].

In Belarus, the relationship between the diaspora and the government remains tense. There is the law “On Belarusians Abroad”, enforced from 2014, and the Advisory Council for Belarusians Abroad under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that operates a programme called Belarusians in the World Source, which aims is to facilitate the interaction of the public administration with diaspora organisations and individuals from communities abroad [49].

The Ukrainian diaspora is also in a distinct category, as the war with Russia has prompted the massive displacement of the population, which does not fit in any of the notions that we have discussed so far. Until the situation settles, we cannot make any accurate assessments of the activities in which the diaspora can be involved until the reconstruction of the country commences. Until then, the Ukrainian citizens residing abroad have an important role to play by raising awareness about the situation and lobbying for the support of Ukraine in their host countries.

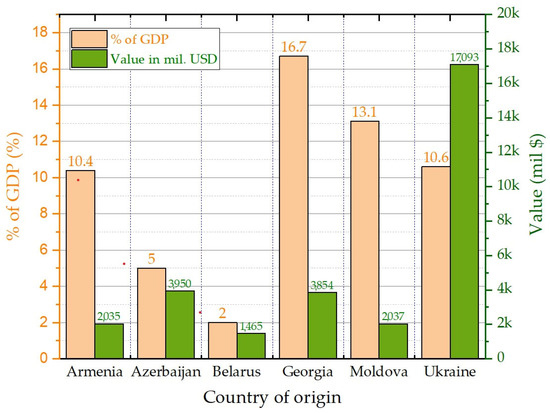

Lastly, the economic and political impact of remittances on the EaP region should not be overlooked. In most of the EaP countries, remittances represent a significant part of the nation’s GDP, specifically, 16.7% (USD 3854 m) in Georgia, 13.1% (USD 2037 m) in Moldova, 10.6% (USD 17,093 m) in Ukraine (data from 2020, before the war), 10.4% (USD 2035 m) in Armenia, 5% (USD 3950 m) in Azerbaijan and 2% (USD 1465 m) in Belarus [40]. This shows the continuous ties between the EaP diasporas and their home countries that make their political engagement more likely. In the context of this study, such engagement can act as a complementary channel for the transmission of gender-equal norms and practices learned abroad, especially when involving highly educated women in STEM. While not a core variable in our evaluative framework, the role of diasporas supports our broader argument regarding norm diffusion and multi-level Europeanisation, and Figure 6 further illustrates this economic impact, showing the proportion of remittances in the GDP of EaP countries.

Figure 6.

The impact of remittances on the countries’ GDP in the EaP region. Source: authors’ graph based on [40] data.

According to multiple studies, diasporas contribute the democratisation of their national governments and their policymaking process through both financial and non-financial means [50,51,52,53]. This manifests through financial remittances and a phenomenon studied since 1998 called social remittances, both of which have the potential to shift political attitudes and behaviours in their home countries. Social remittances represent “ideas, behaviours, identities, and social capital low from receiving to ending-country communities” [54], which can lead to a societal diffusion of norms and values depending on the political environment of the host country. This makes internal Europeanisation among member states even more significant than the external dimension we have highlighted so far.

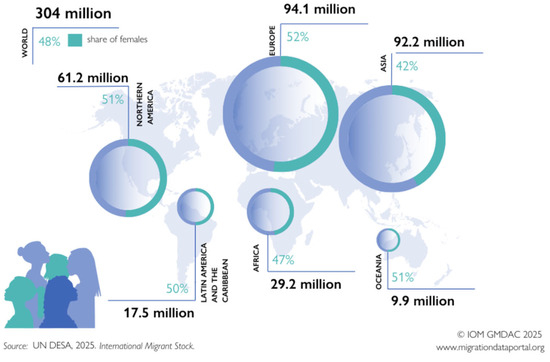

Emigrants therefore have the potential to contribute to reforms in their home countries, and as migration waves are increasingly becoming more feminised (see Figure 7), women have the opportunity to travel, acquire new found confidence in fields that they might have perceived as inaccessible for them, such as STEM and ICT, and apply their new skills and aptitudes to foster change in their home countries. This dimension reinforces our postfunctionalist approach by illustrating how individual agency, transnational identity, and informal norm circulation contribute to the broader diffusion of EU values. While not a central axis of the case study, it provides additional context for understanding the structural factors shaping gender equality in STEM within the EaP.

Figure 7.

International migration by destination region and share of females, as of mid-year 2024. Source: [55].

3.1.6. Summary of Structural Barriers and Misalignments

Based on the information presented so far, we can draw several conclusions. Undoubtably, there are significant challenges in implementing gender equality projects, particularly in higher education and STEM, due to institutional barrier and resistance from universities and governments to adopt gender-sensitive policies. For some institutions, the introduction of GEPs is merely a checkbox for funding eligibility, with the plans’ provisions rarely translating into tangible actions. There are also socio-cultural challenges and, as we have showed so far, the presence of gender stereotypes, especially concerning women in STEM and the workforce are continuously being perpetuated worldwide. Despite policy interventions, societal perceptions in EaP countries continue to discourage women from pursuing careers in STEM, while the ones that complete their education in this field still face difficulties in advancing to senior research positions, limiting their long-term contributions to academia and innovation.

Given the high emigration rates in EaP countries, several projects aim to involve both local women and those abroad in shaping future political agendas. However, these efforts are vulnerable to political change and may not result in tangible policy shifts if national authorities hold differing views.

The misalignment between EU gender policies and national strategies is also concerning. Although EU-funded projects emphasise gender equality, EaP governments’ educational policies often lack strong commitments to gender mainstreaming, and although funding has been repeatedly provided in order to correct this, many EU-funded gender-focused initiatives have limited sustainability once external funding ends, particularly when local governments are unwilling to continue the projects.

In terms of Europeanisation and the gender equality diffusion, internal EU actions clearly exert some spillover effects on the neighbouring regions, not only through programmes such Horizon Europe, the Erasmus+ programme and the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions but also through the model that it sets for EaP migrants that live, work and study in Member States and inevitably bring home some of the values and expertise acquired during their stay.

Thus, the long-term success of EU interventions depends on stronger national policy alignment and sustained institutional commitment both outside and within the EU, as these two aspects are interconnected. This case study indicates that, while the EU continues to reinforce its normative power by promoting gender equality globally, the implementation of GAP III and related policies faces critical limitations in terms of funding allocation, monitoring mechanisms, and engagement with local actors. Our findings align with existing critiques of Europeanisation, which highlight asymmetries in norm diffusion and the challenges of ensuring sustainable policy adoption beyond the EU’s direct jurisdiction. Moreover, the lack of a strong focus on STEM within GAP III suggests that gender mainstreaming efforts remain unevenly distributed across policy areas. Addressing these gaps will require a more strategic and targeted approach, particularly through enhanced funding mechanisms, stronger institutional support, and the better integration of gender policies across EU external action domains. Future research should further investigate the long-term impact of EU-driven gender policies in partner countries and assess whether normative Europeanisation in STEM leads to meaningful structural change or remains primarily symbolic.

3.2. Women in STEM

As shown in the previous section, EaP countries report significantly lower participation rates of women in STEM education and careers. Widespread stereotypes, the lack of institutional support, and unequal domestic responsibilities remain key obstacles, further contributing to the gender gap. By analysing international and European data alongside the EaP context, this section aims to highlight both the shared structural obstacles and the specific dynamics at play in the field, reinforcing the need for more context-sensitive interventions under the EU’s external action.

3.2.1. Systemic Barriers to Women’s Careers in STEM

Despite increased efforts toward gender equality, women in academic STEM fields continue to face persistent and systemic barriers to career advancement, often rooted in institutional cultures, the lack of support structures, and implicit biases that disadvantage women throughout their academic trajectories [56].

In terms of representation in higher education, women are more likely than men to complete a Bachelor’s or Master’s degree, including in STEM fields but when we look at data related to PHD graduates in general and in STEM in particular, their numbers dwindle significantly. Approximately 8% of women graduates choose to pursue a PhD compared to 11% of men, where “women’s representation at Doctoral level has decreased in half of all narrow STEM fields since 2018 and women continue to be underrepresented in half of all narrow STEM fields, including Physical Sciences, Mathematics and Statistics, and Engineering and Engineering Trades” [57].

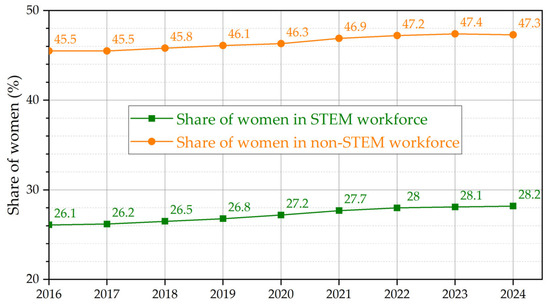

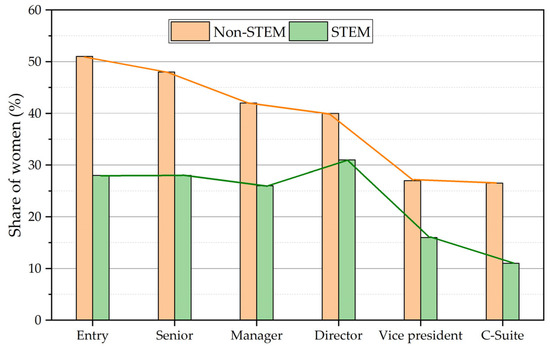

These facts are also tied with the difficulties associated with transitioning from university to the labour market and highlight the fact that even if more women enrol in STEM education, they still encounter barriers when pursuing careers in the field. According to the World Economic Forum, women continue to be under-represented in the STEM workforce where they make up 28.2% compared to 47.3% of the general workforce across all employment fields (Figure 8), while there is also a noticeable gender difference in terms of positions occupied (Figure 9) [58] (pp. 49–50).

Figure 8.

The representation of women in the workforce, STEM vs. non-STEM. Source: [58].

Figure 9.

Representation of women, by seniority, STEM vs. non-STEM roles. Source: [58].

These findings perfectly encapsulate the glass ceiling and the leaky pipeline effect, which postulate that there is an invisible barrier that blocks the rise of women and minorities towards top positions in their careers, respectively, and that there are fewer and fewer women present as you advance in academic levels, which corresponds with the reduced number of women found as you look at the Bachelor–Master–Doctorate trajectory.

A possible explanation for this situation can be found in the Gender Social Norms Index, which looks into men’s biases towards women and women’s self-biases in four areas: the political, educational, economic and physical integrity area. The latest available report has found that almost 90% of people have at least one gender-related bias and that they are found among both men and women and transcend development levels of the countries of origin and the socio-economic and education level of those interviewed, which is especially concerning considering that gender inequality tends to be higher in countries with greater gender bias [59].

The inclusion of gender experts in the Horizon Europe project’s evaluation panels and the fact that having gender equality plans is now compulsory for all the funding applications made under this programme not only impacts the promotion of women in STEM and the reinforcement of gender equality inside the EU but also beyond. This sets a precedent of good practices and it is imposed to partner institutions from outside the EU as well.

3.2.2. Migration, Return, and Transnational Gender Norms

It is important to note that in the case of migrant women that study STEM in European universities, this effect can be propagated even further if we take return migration into account. As various authors have noted, there are obvious barriers when it comes to employment opportunities for women with an STEM background in their host countries [60,61,62].

In fact, according to the OECD data, a significant number of migrants do not permanently settle in their host country and instead choose (in the case of voluntary returnees) to return to their country of origin within 5 years of moving. On average, half of the migrants that came to Europe between 2010–2014 left, the numbers varying by country, as showcased by the retention rate of immigrants in Figure 10 [63].

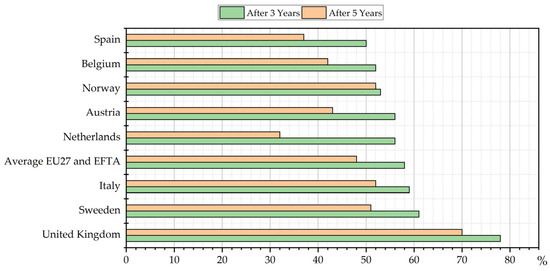

Figure 10.

Retention rates for EU-27 and European Free Trade Area immigrants in selected European countries. Note: Entry period 2010–2014. Population aged 15 and over. Source: [63].

The return migration discourse usually circles around the family and community context, where “family migrants and those arriving for humanitarian reasons are most likely to remain”, while at the same time, “the main driver for return migration to origin countries is family related” [63]. It was also observed that the least likely category to remain in the host country is that of international students pursuing their degree [63,64,65].

It has been shown that return migrants with higher education levels have higher employment rates in their country of origin compared to the general population, which also corresponds with higher wages and higher productivity levels [65]. Even so, higher wages in the country of origin do not correspond necessary to higher wages compared to those they would have in their host country if they stayed; nevertheless, many still choose to return.

This pattern is visible among STEM graduates globally. According to Sun and Wu, although international STEM graduates have the advantage of greater mobility in the global employment market than other fields, there is still a significant number of them that return home not solely for professional reasons but also due to family ties, perceived financial opportunities or other personal reasons. While their study focused on return migration to China, the findings reflect broader gendered dynamics observed across migration systems—particularly the disproportionate role of women as caregivers, which often makes family considerations more decisive than career advancement when it comes to return migration [66].

Women STEM graduates are definitely a net positive for their country of origin. They represent a highly skilled workforce that is in continuous demand, who have completed their education and gained research experience at no cost to the education system of their country of origin and who will also contribute to their community not only through their work in itself but also through the diffusion of gender-equal values acquired during their education abroad.

4. Discussion

This section offers a critical reflection on the research findings in light of the global landscape and the EU’s normative framework on gender equality in STEM. It examines the role of various international actors and evaluates the EU’s position as a promoter of gender values beyond its borders. The discussion focuses on the implementation and shortcomings of GAP III, considering the extent to which these policies resonate with or clash against domestic realities in the EaP countries.

By applying the proposed evaluation grid, we observe that although several initiatives demonstrate effectiveness in short-term institutional adaptation and the increased visibility of women in STEM, their sustainability varies significantly. In cases where national strategies were aligned with EU objectives and institutional support mechanisms existed (e.g., GEPs supported by local funding), outcomes proved more durable. Conversely, where EU support remained externally driven and insufficiently embedded locally, the results often lacked long-term continuity.

4.1. The Global Context of Actors Promoting Gender Equality in STEM

Gender equality in STEM has been a priority for numerous global actors, as it is considered vital for economic competitiveness and social stability. According to the World Economic Forum’s 2024 Global Gender Gap Report, women continue to face systemic barriers in accessing STEM education and careers, with the gender gap in many countries remaining wide [58].

Over the years, several initiatives have been launched to address this issue. In addition to the UN’s sustained efforts, examples include Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy, launched in 2017, which places women’s rights and empowerment at the centre of international development efforts, and the USAID’s major roles in advancing women’s participation in STEM [67].

Nevertheless, the impact of the Trump Administration’s policies on global gender equality initiatives, particularly those focused on women in STEM, has been significant, particularly through its reduction in USAID funding. In addition to reducing funding, the Trump administration introduced conditionalities tied to the reduction or cancellation of U.S. financial support to international programmes unless they aligned with specific U.S. policy goals. This included conditions on UN agencies that promoted reproductive health services, a move that disproportionately affected the gender equality agenda. Such actions directly contradicted the normative framework supported by previous administrations, including efforts to integrate gender mainstreaming in international development and education, including STEM initiatives, and created significant political tensions while weakening the U.S. influence in global discussions on gender equality in STEM, a domain in which the U.S. has historically been a leader.

These policies led to a shift in the international cooperation landscape, especially in terms of how organisations like the USAID and the United Nations could effectively collaborate on gender equality initiatives. While these actions have led to short-term reductions in the resources available for gender-focused programmes, they also placed pressure on other global actors—like the EU—to increase their investments in gender equality, compensating for the decline in U.S. leadership.

In contrast to the fragmented and often inconsistent approaches taken by other global actors, the European Union has sought to maintain a coherent and structured commitment to gender equality across both its internal and external policies. As the influence of traditional players like the United States diminished in recent years—particularly during the Trump administration—the EU has increasingly positioned itself as a normative leader in promoting women’s empowerment in STEM. This transition sets the stage for a closer examination of the EU’s flagship policy in this area, GAP III, which aims to consolidate and project the Union’s gender equality agenda in its external action.

Just like the process of Europeanisation, which manifests similarly inside the EU and outside of it, we can draw a clear connection between the action taken by the EU for tackling gender issues internally and its policies related to gender equality abroad. All the GAPs so far have reflected the objectives set by the EU internally in its Gender Equality Strategy, and when the current one, GAP III, was launched, Josep Borrell, then Vice-President of the European Commission and High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, stated that “Ensuring the same rights to all empowers our societies. It makes them richer and more secure. It is a fact that goes beyond principles or moral duties. The participation and leadership of women and girls are essential for democracy, justice, peace, security, prosperity and a greener planet” [11], but achieving these ideals is still proving difficult.

4.2. GAP III’s Implementation and Challenges

GAP III outlines a set of ambitious goals such as ensuring that 85% of all new external relations actions will contribute to gender equality and women’s empowerment; sharing a strategic vision and close cooperation with Member States and partners at multilateral, regional and country levels; accelerating progress by focusing on the key thematic areas of engagement; and leading by example and measuring results appropriately [11]. Initially, the period of implementation for GAP III was set from 2021 to 2025, but instead of moving forward with a new and improved GAP IV, it was extended until 2027 despite several issues raised by feminist groups, civil society organisations (CSOs) and other women rights organisations in general during the initial period of implementation [68,69,70].

As mentioned before, GAP III represents the current policy framework used by the EU for spreading gender equality outside its borders. Learning from the critiques addressed to the European Neighbourhood Policy, GAP III has implemented Country Level Implementation Plans (CLIPs) and focuses on dialogue with the partner countries in order to fulfil its commitment to mainstream gender equality in all areas of its external action, especially as the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (WPS) has been added to the GAP’s objectives.

Despite numerous achievements so far, there are challenges that cannot be ignored. As highlighted in the Midterm Evaluation of the EU Gender Action Plan III and by numerous representatives of the civil society such as CONCORD (the European Confederation of NGOs working on sustainable development and international cooperation, which represents over 2600 of NGOs), the main hurdles in implementing GAP III policy are a lack of sufficient human resources and training for gender equality, the need for clearer guidelines and a better implementation and monitoring of the policy, especially concerning WSP, the need for a better analytical assessment of the quality and parameters of gender-related actions, as well as their monitoring, the need to make funding more accessible and to ensure meaningful, safe and inclusive dialogue with local women’s rights organisations, etc. [70,71].

CONCORD and other organisations also previously noted that unless the development pillar and gender policy they put forward truly become complementary with the other three pillars (foreign, security, and trade), their implementation and results will remain limited. Although the promise that 85% of the Union’s actions will contribute to gender equality and women’s empowerment is on track to be fulfilled, the main focus should not be on the number of actions that are supported through this plan but on the amount of funding that they receive; therefore, from this point of view, a clear commitment regarding a certain percentage of the EU’s official development assistance (some sources suggested an amount of 20%) addressed specifically for gender-related projects would have led to a better goal than the 85% promise in regard to the number of actions implemented [68,69,72].

In terms of the Union’s overarching approach to this policy, the midterm evaluation report reiterates the purposeful alignment between gender equality and women empowerment as a European value and the EU’s policies in terms of global development and enlargement. Also, when it comes to the results of mainstreaming gender in all policy areas, GAP III proved quite effective in incentivising countries to adapt their regional strategies to be more gender inclusive. As such, a key example given was the Multi-Annual Indicative Programme Asia and the Pacific 2021–2027, which clearly set goals and indicators for advancing gender equality while its predecessors did not even mention women, gender or empowerment. Likewise, the 2020 EU document “Towards a comprehensive Strategy with Africa—a partnership for sustainable and inclusive development” has multiple reference points that follow those found in GAP III, while previous initiatives barely mentioned key points for advancing gender equality such as creating jobs for women but did not offer any further guidelines nor recommendations. In the same vein, an EU initiative, the Investment Climate Reform Facility (which offers technical assistance and support for improving the business environment in Africa, the Caribbean and Pacific), was updated in order to better take into account women’s economic empowerment, a change that is attributed by the EU personnel to GAP III [71].

This being said, we want to bring our own set of criticisms to GAP III by highlighting the fact that there is little mention of women in STEM in the policy, while the midterm report fails to address any reference at all. The original text of the policy admits that in terms of promoting gender equality in education “Gender stereotypes limit girls’ aspirations for science and engineering careers and discourage boys from pursuing jobs in the care sector” and it proposes actions such as “increasing investment in girls’ education to achieve equal access to all forms of education and training, including science, technology, engineering and maths, digital literacy and skills, and technical and vocational education and training” [12]. Regardless of this, the midterm evaluation report does not touch at all on any actions that were implemented to achieve this goal. In light of this omission, one way forward would be to introduce clear, STEM-focused targets and monitoring indicators in future GAP iterations or complementary policy frameworks. These could include earmarked funding for girls’ and women’s participation in STEM, STEM-specific gender parity goals, and support for national strategies that promote inclusive science education and innovation.

4.3. Assessing the Validity of the Research Hypothesis, Limitations and Future Work

The EU has consistently prioritised gender equality within its internal and external policies. The Gender Action Plan III (GAP III) [11,12] is the EU’s main strategy to promote gender equality globally, including in STEM fields. GAP III focuses on increasing women’s participation in education, leadership, and innovation, particularly in sectors critical for economic growth and sustainability, such as STEM. The Horizon Europe programme mandates that research institutions implement GEPs in order to receive funding, ensuring gender considerations are embedded in scientific research and innovation [11,12]. Moreover, the Erasmus+ programme encourages gender equality in education and training, providing support to women pursuing STEM education and careers [73].

Reflecting on our initial research hypothesis, we can draw several key conclusions from the findings presented in this paper.

Our hypothesis (H: The effectiveness of EU-driven Europeanisation in promoting gender equality in STEM is influenced by political, socio-economic, and cultural barriers in EaP countries, which may limit the uptake and sustainability of these measures) is strongly supported by our findings. While the EU provides the policy framework, funding, and incentives for gender equality in STEM, the actual success of these policies depends heavily on domestic factors such as political will, societal norms, economic constraints, and institutional commitment. Challenges such as persistent gender biases in STEM education, the glass ceiling in academia, and the under-representation of women in research leadership positions remain significant barriers that EU policies alone cannot fully address.

The postfunctionalist framework helps explain why even well-funded programmes may produce uneven outcomes: local actors do not simply implement external models—they reinterpret them through national lenses. While some institutions embrace gender mainstreaming as a sign of progress and innovation, others may treat it as symbolic compliance or resist it altogether. These variations are not failures of Europeanisation but manifestations of its contested nature in pluralist societies.

Thus, while the EU plays an essential role as a normative gender actor in the EaP region, the extent of its influence varies based on national and institutional contexts. Future research should focus on measuring long-term impacts, assessing the sustainability of EU-funded gender initiatives, and exploring how local actors—civil society, academia, and policymakers—can enhance and internalise gender mainstreaming efforts beyond EU-driven incentives.

While this research provides a detailed analysis of the EU’s role in promoting gender equality in STEM across the EaP countries, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the qualitative nature of the research and the selective focus on case studies may limit the generalisability of the findings. Second, inconsistencies in data availability and differences in national statistical methodologies affect the accuracy of regional comparisons. Third, the influence of political instability and restricted access to official data in some countries can hinder comprehensive assessment. Future studies would benefit from integrating longitudinal data and quantitative metrics to further strengthen the analysis and provide deeper insights into the sustainability of EU-driven gender equality efforts.

5. Conclusions

The impact of Europeanisation on gender equality policies, particularly in STEM fields, is complex and shaped by both EU-driven initiatives and domestic socio-political contexts. EU funding programmes such as Horizon Europe and Erasmus+ have contributed to increasing women’s participation in STEM education and research. Their long-term effectiveness depends on sustained national commitment and structural reforms in partner countries. This aligns with the hypothesis formulated, which proposed that political, socio-economic, and cultural barriers in EaP countries influence the uptake and sustainability of EU-driven Europeanisation.

The adoption of GEPs in research institutions receiving EU funding demonstrates the potential of conditionality as a tool for norm diffusion, yet its impact is often constrained by institutional resistance and socio-cultural barriers in EaP countries. For example, national education policies often lack alignment with EU priorities, limiting the transformational potential of EU interventions.

Cultural norms, political resistance, and fragile institutional frameworks frequently undermine the effectiveness of EU initiatives. We have highlighted these tensions, particularly in the implementation of GAP III, and noted the insufficient integration of STEM-specific objectives in its midterm evaluation. Even when external funding and expertise are available, the internalisation of EU values largely depends on domestic actors’ willingness and capacity to adopt these norms in a sustainable manner.

The EU’s comprehensive approach, integrating gender equality into both domestic governance and external relations, sets it apart from other global actors playing critical roles in promoting gender equality in STEM. By leveraging its normative power, the EU influences neighbouring countries to adopt gender equality measures, particularly in STEM education and innovation. To amplify its global impact as a gender actor, the EU should continue strengthening partnerships with local stakeholders—NGOs, academia, and advocacy groups—who can carry forward these efforts beyond the lifespan of EU-funded projects. Additionally, a more strategic focus on STEM within GAP III and its successors is needed, as the inclusion of specific, measurable indicators for gender equality in STEM would provide a clearer picture of progress and help tailor future interventions to the realities on the ground.

In the current international context, efforts to promote gender equality in STEM are affected by the overlapping roles and activities of multiple global actors, making it difficult to attribute success to any single institution. The synergy between the EU and these organisations is crucial for a coherent approach, yet recent developments, such as the policies of the Trump administration, which weakened US–UN collaboration and reduced funding for gender-focused initiatives, have put this partnership at risk. In the long run, the EU may find itself as the only major actor consistently investing in gender equality at the international level. Therefore, the continuity and sustainability of the EU’s gender policies depend not only on its own commitments but also on long-term international cooperation and its ability to maintain a normative leadership position in an evolving global landscape.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, G.-R.I., C.P. and M.M.; methodology, C.P., M.M. and G.-R.I.; validation, C.P. and M.M.; formal analysis, G.-R.I. and C.P.; writing—G.-R.I., C.P. and M.M.; supervision, C.P. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EaP | Eastern Partnership |

| EU | European Union |

| GAP III | Gender Action Plan III |

| GEP | Gender Equality Plans |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organisation |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| STEP | Statistics Through Eastern Partnership |

References

- Leach, M. (Ed.) Gender Equality and Sustainable Development, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaquette, J.S. Women/Gender and Development: The Growing Gap Between Theory and Practice. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2017, 52, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugarova, E. Gender Equality as an Accelerator for Achieving the SDGs; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.undp.org/publications/gender-equality-accelerator-achieving-sdgs (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Momsen, J. Gender and Development, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pető, A.; Thissen, L.; Clavaud, A. (Eds.) A New Gender Equality Contract for Europe: Feminism and Progressive Politics; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Factsheet on the New Framework for Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Through EU External Relations (2016–2020); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/memo_15_5691 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Samson, H. EU Statement—UN International Day of Women and Girls in Science—11 February 2025. In Proceedings of the United Nations International Day of Women and Girls in Science, New York, NY, USA, 13 February 2025; Available online: https://south.euneighbours.eu/news/eu-statement-un-international-day-of-women-and-girls-in-science/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Rosen, M.A. Engineering Sustainability: A Technical Approach to Sustainability. Sustainability 2012, 4, 2270–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manners, I. Normative Power Europe: A Contradiction in Terms? J. Common Mark. Stud. 2002, 40, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmelfennig, F.; Sedelmeier, U. The Europeanization of Central and Eastern Europe; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Gender Action Plan III—A Priority of EU External Action; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_2184 (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- European Commission. Joint Communication on the Gender Action Plan III; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-01/join-2020-17-final_en.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Leuffen, D.; Rittberger, B.; Schimmelfennig, F. (Eds.) Postfunctionalism. In Integration and Differentiation in the European Union; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, L.; Marks, G. Grand Theories of European Integration in the Twenty-First Century. J. Eur. Public Policy 2019, 26, 1113–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T. Grand Theories of European Integration Revisited: Does Identity Politics Shape the Course of European Integration? J. Eur. Public Policy 2019, 26, 1213–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaelli, C.M. The Europeanization of Public Policy. In The Politics of Europeanization; Featherstone, K., Radaelli, C.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaelli, C.M. (Ed.) The Europeanisation of Member State Policy. In The Member States of the European Union, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladrech, R. Europeanisation of Domestic Politics and Institutions: The Case of France. J. Common Mark. Stud. 1994, 32, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmelfennig, F. EU External Governance and Europeanisation Beyond the EU; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börzel, T.A.; Risse, T. Conceptualizing the Domestic Impact of Europe. In The Politics of Europeanization; Featherstone, K., Radaelli, C.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, P.; Pomorska, K.; Tonra, B. The Domestic Challenge to EU Foreign Policy-Making: From Europeanisation to De-Europeanisation? J. Eur. Integr. 2021, 43, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. De-Europeanisation in European Foreign Policy-Making: Assessing an Exploratory Research Agenda. J. Eur. Integr. 2021, 43, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domaradzki, S. Opportunistic Legitimisation and De-Europeanisation as a Reverse Effect of Europeanisation. In The Limits of Europe; Foster, R., Grzymski, J., Eds.; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2022; pp. 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhari Gulmez, D. Europeanisation in a Global Context; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European External Action Service (EEAS). Eastern Partnership; 2022 (March 17). Available online: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eastern-partnership_en (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Delegation of the European Union to the Republic of Belarus. The European Union and Belarus; 2024 (October 1). Available online: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/belarus/european-union-and-belarus_en?s=218 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Delegation of the European Union to Georgia. Extracts on Georgia from the Conclusions of the European Council; 2024 (June 28). Available online: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/georgia/extracts-georgia-conclusions-european-council_en?s=221 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- European Humanities University. An Atmosphere of Support and the Feeling That You Can Do Anything. The Women in Tech Project Sums Up the Year; 2023 (January 9). Available online: https://en.ehu.lt/news/women-in-tech-project-sums-up-the-year/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- European Union. Women Taking Over Tech in Belarus; Within “Towards a Gender Equal World: The EU Gender Action Plan III, 2025” Group (Updated: March 25). Available online: https://capacity4dev.europa.eu/groups/public-gender/info/women-taking-over-tech-belarus-0_en (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action. WE United for Ukraine; n.d. Available online: https://energypartnership-ukraine.org/we-united-for-ukraine/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- EU Neighbours East. Manual for Gender Equality Action Plans for Higher Education and Research Institutions; 2025 (February 5). Available online: https://euneighbourseast.eu/news/publications/manual-for-gender-equality-action-plans-for-higher-education-and-research-institutions/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- EU4Digital. EU Initiative Mentoring Georgian Women in Technology Follows EU4Digital Guidance; 2024 (April 3). Available online: https://eufordigital.eu/eu-initiative-mentoring-georgian-women-in-technology-follows-eu4digital-guidance/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- STEP. Gender Statistics in the Eastern Partnership (EaP)—Progress Towards Gender Equality: What Do the Statistics Tell Us? 2022. Available online: https://euneighbourseast.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/step_brochure_gender-eq_en-1.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- European Union. Gender Equality and Post-2020 Eastern Partnership Priorities: A Guide on How to Promote Gender Equality in Policy, Programming and Reform Work; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://euneighbourseast.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/gender-equality-and-post-2020-eastern-partnership-priorities_feb2022.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- UNDP. 2023 Gender Social Norms Index (GSNI): Breaking Down Gender Biases: Shifting Social Norms Towards Gender Equality—Report; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/hdp-document/gsni202303.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- EU4Digital. The EU4Digital Initiative; n.d. Available online: https://eufordigital.eu/discover-eu/the-eu4digital-initiative/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- EaPConnect. Celebrating 10 Years of EaPConnect: Voices from the NRENs; 2025 (March 21). Available online: https://eapconnect.eu/stories/celebrating-10-years-of-eapconnect-transforming-research-education-and-society/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- European Commission. Gender Equality in Research and Innovation; n.d. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/strategy/strategy-research-and-innovation/democracy-and-rights/gender-equality-research-and-innovation_en (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Gulina, O.R. Diaspora Engagement Eastern Europe & Central Asia Factsheet Dossier; EUDiF: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; (Updated October 2021); Available online: https://diasporafordevelopment.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/EECA_CF_dossier.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- EU Global Diaspora Facility. Diaspora Engagement Map; 2023 (2020, last update December 2023). Available online: https://diasporafordevelopment.eu/diaspora-engagement-map/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Armenpress. Armenia Develops 2023–2033 Diaspora Partnership Strategy Ahead of 2nd Global Summit; 2024 (January 29). Available online: https://armenpress.am/en/article/1129041 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Office of the High Commissioner for Diaspora Affairs. iGorts. 2025. Available online: http://diaspora.gov.am/en/programs/25/fellowship (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Armenpress. Over 250 Diaspora Armenian Specialists Joined “iGorts” Program Since 2020; 2025 (March 19). Available online: https://armenpress.am/en/article/1214757 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Gaboyan, G. Applications Open for DiasPro Professional Volunteer Program. Armenpress; 2025 (March 6). Available online: https://armenpress.am/en/article/1213640 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Office of the High Commissioner for Diaspora Affairs. DiasPro. 2025. Available online: http://diaspora.gov.am/en/programs/39 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- State Committee on Work with Diaspora of the Republic of Azerbaijan. History and Purpose of Establishment of the Committee; n.d. Available online: https://diaspor.gov.az/en/page/history-and-purpose-of-establishment-of-the-committee-14 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Government of the Republic of Moldova. Biroul Relații cu Diaspora; n.d. Available online: https://brd.gov.md/brd/despre-noi/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- DiasporaConnect. O Diasporă Puternică Este o Diasporă Conectată; n.d. Available online: https://diasporaconnect.md/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus. Belarusians Abroad; n.d. Available online: https://mfa.gov.by/en/mulateral/diaspora/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Meseguer, C.; Burgess, K. International Migration and Home Country Politics. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2014, 49, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodigiani, E. The Effect of Emigration on Home-Country Political Institutions. IZA World Labor. 2016, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsbai, T.; Rapoport, H.; Steinmayr, A.; Trebesch, C. The Effect of Labor Migration on the Diffusion of Democracy: Evidence from a Former Soviet Republic. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2017, 9, 36–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksanyan, A.; Bejanyan, V.; Dodon, C.; Maksimenko, K.; Simonian, A. Diaspora and Democratisation: Diversity of Impact in Eastern Partnership Countries. Glob. Campus Hum. Rights J. 2019, 3, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, P. Social Remittances: Migration Driven Local-Level Forms of Cultural Diffusion. Int. Migr. Rev. 1998, 32, 926–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Migration Data Portal. Women and Girls on the Move. 2025. Available online: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/women-girls-migration (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- O’Connell, C.; McKinnon, M. Perceptions of Barriers to Career Progression for Academic Women in STEM. Societies 2021, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. She Figures 2024: Gender in Research and Innovation—Statistics and Indicators; Directorate-General for Research and Innovation: Luxembourg, 2025; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/592260 (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Pal, K.K.; Piaget, K.; Zahidi, S.; Baller, S. Global Gender Gap Report 2024; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-gender-gap-report-2024/digest/ (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- UNDP. 2023 Explore Gender Social Norms Index. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/2023-gender-social-norms-index-gsni#/indicies/GSNI (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Grigoleit-Richter, G. Highly Skilled and Highly Mobile? Examining Gendered and Ethnicised Labour Market Conditions for Migrant Women in STEM Professions in Germany. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2017, 43, 2738–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzani, D.; Crivellaro, F.; Grimaldi, R. Highly Skilled, Yet Invisible: The Potential of Migrant Women with a STEMM Background in Italy between Intersectional Barriers and Resources. Gend. Work Organ. 2021, 28, 2132–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Crivellaro, F.; Bolzani, D. Perceived Employability of Highly Skilled Migrant Women in STEM: Insights from Labor Market Intermediaries’ Professionals. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Return, Reintegration and Re-Migration: Understanding Return Dynamics and the Role of Family and Community; OECD: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisser, R. Internationally Mobile Students and Their Post-Graduation Migratory Behavior: An Analysis of Determinants of Student Mobility and Retention Rates in the EU; OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2016; Volume 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, J. Who Benefits from Return Migration to Developing Countries? IZA World Labor 2021, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wu, H. Academic Return Migration Amidst North-to-South Trend: An Integrative Inquiry into the Case of Chinese International STEM Researchers. Stud. High. Educ. 2024, 1–16, [advance online publication]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]