1. Introduction

Prefigurative politics is a social movement strategy that focuses on building the transformed world we want to live in, as opposed to the strategy of fighting against injustice or oppression. As the Industrial Workers of the World said in the early 1900s, it is the effort to “form the structure of the new society within the shell of the old” [

1]. The approach is often associated with the Occupy movement, where activists around the world physically occupied public spaces to practice systems of mutual care and participatory democracy. While the prefigurative approach is often defined in contrast to defensive protest, many activists believe both approaches are needed. “Many US solidarity economy activists have labeled their approach fight and build. Fight and build can suggest a dual orientation: attending to the world as it is and a transformative politics that is building other worlds” [

2].

Designers seeking to contribute to systemic social transformation can find powerful partners in collectives engaged in prefigurative politics. Prefigurative collectives like mutual aid networks, worker cooperatives, and community land trusts are already building alternative systems in the present; systems that challenge assumed social structures like racial capitalism. For example, a mutual aid network may focus on a material task like delivering food to families who need it. Along the way, they build relationships, systems, language, visuals, technologies, and physical and digital tools and materials, all of which defy normative ways of doing things in favor of alternative ways that envision transformed social systems. Designers can support these collectives by co-creating everyday tools that are embedded with their transformative visions. For such collaborations to succeed, designers and prefigurative partners must be able to communicate about the foundational transformation the collective is working toward. This can be challenging when prefigurative collectives lack a shared or explicit articulation of the larger transformation they envision. In this paper, I will discuss a design project that draws on participatory and speculative design approaches to help bring to the surface prefigurative partners’ post-capitalist visions, laying the groundwork for design collaborations that can materialize the transformation they seek.

Before looking at the project, let’s peek into what a prefigurative collective can look like. In the summer of 2020, after being intrigued by prefigurative politics for a few years, I had the opportunity to join a mutual aid network. In a New York City struck by the COVID-19 pandemic, these collectives seemed to be popping up in every neighborhood. They were inspired by calls from activist scholars like Dean Spade, who published a YouTube video the year before called “Shit’s Totally FUCKED! What Can We Do?: A Mutual Aid Explainer” [

3], and was well-positioned to publish a book in 2020 on the subject [

4]. In New York, collectives were being started by people out of work, or with time to spare around their newly virtual desk job. Mutual aid networks organized to deliver groceries and other basic supplies to families in need, or vulnerable neighbors who couldn’t leave their homes. When we weren’t standing in the food pantry line or delivering to nearby apartments, we gathered over Zoom to study and discuss the long history of mutual aid. We referred to a lineage of efforts organized by people whose needs were not being met by the systems around us– the Black Panther Party who created free health clinics and free breakfast programs accessible to all, the Young Lords who followed in their footsteps in Chicago and New York, and before them, fraternal societies that welcomed new immigrants, and the underground railroad that sheltered people fleeing slavery. We also looked to other efforts of prefiguration happening today, such as the Zapatistas in Chiapas, organizing for indigenous self-determination; Cooperation Jackson, a network of worker cooperatives and other solidarity economy initiatives in Jackson, Mississippi; and Rojava, an autonomous region in Syria experimenting with direct democracy.

Working with the New York mutual aid network showed me how the act of prefiguration came to life in tiny collective decisions. In weekly Zoom meetings, we discussed where we should buy our groceries, how we should talk about the network on our Instagram, and whether we should accept fiscal sponsorship from an organization that could support tax-deductible donations. It became clear that different members had different guiding intentions and that these intentions had a big impact on how they wanted to shape our daily operations. Some wanted to distribute as much food to as many people as possible, to address the steep need and inequality exposed by the pandemic. Those members said we should buy our groceries in bulk, as cheaply as possible; solicit volunteers from anywhere in the city; and yes, of course, accept fiscal sponsorship. Others were interested in that idea of prefiguration. They sought to build and practice support systems and community relationships that differed from those offered by government agencies, nonprofits, and businesses. They also wanted to address people’s needs, but they wanted to do so with different priorities. Instead of scaling up a charity service, those who sought prefiguration wanted to practice solidarity, reciprocity, and deep supportive relationships between neighbors. In response to the questions we discussed, they thought people should buy groceries where they usually shopped, or maybe we should partner with a neighborhood community garden; the collective’s Instagram should focus on solidarity and not differentiating between volunteers and recipients; and they wondered if fiscal sponsorship was a slippery slope leading to nonprofit status. These members saw our work together as an opportunity to explore political and economic systems beyond capitalism and colonial development.

Working with the New York mutual aid network helped me understand the challenges and opportunities around designing with prefigurative politics. I was eager to work on designed tools and materials with the collective and to think explicitly about how we embed those tools with our transformative vision. However, this required a shared articulation of the change we were working towards. In reality, the collective was composed of members who had varying degrees of interest in foundational transformation. Everyone was there because they cared about people in the city and wanted to address the need they saw, but this didn’t always translate to seeking fundamental social changes. Some saw class divides and inequality as an inevitable part of life that could only be addressed through charitable giving. It was difficult to focus on the challenging and frivolously abstract task of aligning on a philosophical vision when everyone was focused on immediate impact in the crisis of the pandemic.

1.1. Design and Prefigurative Politics

Designers have been intrigued by prefigurative politics for some time. In 2007, a project among European universities published a book on Creative Communities about “people inventing sustainable ways of living” [

5]. It catalogued projects like ecovillages, local currencies, time banking, urban farms, and cooperative businesses. While this publication remained politically neutral, I would classify these as prefigurative projects because they involve small collectives of people prefiguring alternative social systems based on fundamentally different values. Time banking, for example, prefigures a system where everyone’s time costs the same, and where traditionally feminine caretaking tasks are of equal worth to traditionally masculine tasks of industry and production. Arturo Escobar compares these European life projects to the indigenous struggle for self-determination in South America—Buen Vivir, post-development, and transitions to post-extractivism [

6]. He references, for example, the Zapatistas, who prefigure a Good Government model grounded in direct democracy. Programs like Carnegie Mellon’s Transition Design Ph.D. and the International DESIS Network (Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability) have built upon the Creative Communities publication, stating that design-led social transition should amplify and extend the work of grassroots collectives that prefigure alternatives [

7,

8]. And Carl DiSalvo, author of

Adversarial Design, addresses prefigurative politics directly as an approach to political design in an article for the

Journal of Design Strategies [

9]. Bianca Elzenbaumer and Fabio Franz created their design practice by prefiguring alternative economic models with their community [

10], building on J.K. Gibson-Graham’s community economies [

11]. Recently, papers at the Participatory Design Conference engage with “commoning” and even call for “prefigurative design” [

12,

13]. All of these authors argue that designing for transformation can be most effective if we work with prefigurative movements that already exist.

Taking on this call to design within prefigurative efforts raises unique challenges. How can we design to enact foundational social transformation within the world we have? How do we need to design differently in this context [

14]? Design as a professional field (especially industrial design) was developed through industrial ‘progress’ and expansion of capitalism and colonialism. Is this really the kind of practice that could help us refuse those systems and create something different [

6,

15]? Yet the practice of design has a unique ability to make abstract ideas visible and material. Could designers help prefigurative collectives achieve more momentum and alignment by expressing their transformative visions in the form of their everyday activities and materials?

1.2. Speculative Design in Prefigurative Politics

I have explored speculative design as a practice that could contribute to these questions. Popularized by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby in their book

Speculative Everything [

16], speculative design is a practice that does not seek to solve problems or create objects that people can use today, but rather to make things that could exist in alternative possible futures, to provoke thinking about what those transformed futures might be like. Speculative designers create three-dimensional, lifelike models of everyday objects that appear strange or unfamiliar, provoking the viewer to consider how the world around the object must have transformed. Successful speculative projects use only physical form to express this social transformation– for example, Ani Liu’s piece

The Surrogacy—a transparent model of a pregnant pig implanted with human fetuses [

17], or the Extrapolation Factory’s

Transition Habitats, a series of brightly colored metal mail boxes formed to invite messages from non-human beings like lichen and migratory birds [

18]. “They do not “fit” into today’s world… This is what makes them “unreal”. They are at odds with how things are” [

16] (p. 92). Typically, speculative design projects are displayed in design magazines and art museums. An important question is often raised about who gets to pose questions in this format, and who is the audience that they provoke?

Some address this question by using speculative design in a participatory way with communities. In 2015–18, I started working with participatory speculative design by facilitating collaborative imagination around futures without punitive justice, policing, and prisons, in partnership with people living in heavily policed neighborhoods, like young people on probation in Harlem, New York, and people working on reform, like the Center for Court Innovation. In Ferguson, Missouri, I worked with residents engaged in a court-ordered police reform process. I facilitated collaborative activities to support these partners in reflecting on what justice means to them, and what they want from a fundamentally transformed justice system. In Ferguson, I held iterative workshops with residents and designers to create three scenic installations that portrayed diverse visions of futures without policing [

19].

In these contexts, speculative design was a tool to spark conversations. When I created speculative objects and images in response to participants’ ideas, it helped to provoke more vivid visuals about what the future they imagined looked like in everyday life. For example, before creating the installations, participants said things like “community members need to watch out for each other”. Then, when confronted with a scene showing neighbors watching out for each other in front of houses on a suburban block, participants added that there should be more lush greenery, houses should all be different, and there should be more celebration of individual personality. This opened up a deeper discussion about what we need to do today to enable this kind of future.

At the same time, the speculative design approach can be inaccessible. Speculative objects leave a lot unsaid, whereas people are more familiar and comfortable with futures explored through stories in film, books, etc. It was difficult to convince people to participate in this work, it took a lot of labor to produce artifacts, and in the end the project had minimal impact on those who used the artifacts to explore alternative possibilities.

After concluding these projects, I started to wonder if prefigurative politics could be a place for speculative design to land. Prefigurative projects are inherently speculative. Collectives are already acting out a transformed world in the present day. For example, the mutual aid network I described was coordinating neighbors so that some could deliver food from the grocery store to others who weren’t able to leave their homes. Through this activity, they were prefiguring, or speculating about, a future of community care and solidarity built on close neighbor connections. In their daily work, the mutual aid network designs things all the time, like a spreadsheet to match neighbors’ needs with other neighbors who can help. They also design roles and processes in the organization, Instagram posts, and even a wooden enclosure to keep a community fridge insulated from the cold. These things address the practical problems the network encounters in its daily operations. What if we could combine a speculative design approach with this practical problem-solving? For example, how could that mutual aid spreadsheet visually express the transformative vision of neighborhood solidarity? How could the community fridge emphasize its oddness, as a rare place where food is stored at the community level and not in a family home? Could these objects serve as sites of agonistic pluralism and consensus, where collectives hash out the transformative vision of their work in order to embed it in the design [

20,

21]? Could these odd speculative objects that show a transformed vision serve as a reminder of what the collective is working towards?

I began to pursue this idea after moving to western Massachusetts in 2022, by getting to know prefigurative collectives in the area. I identified many, though they did not use the word “prefigurative” to describe themselves. Instead, some collectives speak about their role in the “solidarity economy” with phrases like “Imagine an economy that works for everyone” [

22]. Others highlight their commitment to community, equity, care, justice, and/or collective healing. I also reached out to worker cooperatives, mutual aid networks, and community land trusts because these models reject key elements of capitalism. For example, in a worker cooperative, workers own the means of production, which rejects a capitalist division between workers and owners [

23].

As I began to speak with these collectives about designing speculative tools together, I ran into a challenge. People did not know what I meant when I referred to their vision of the future or the transformation they are working towards. Sometimes, they responded by sharing their organization’s goals and plans for the next couple of years, while I had a much longer timeframe in mind. I began to see that members held a diverse range of views on social transformation. While some members of these collectives consider themselves to be working towards radical change, others do not. They often did not have the luxury of time to discuss the broader changes they were working towards. This is the context that sparked River Valley Radical Futures.

2. River Valley Radical Futures

Between September 2023 and December 2024, I led a project with student research assistants at Smith College to frame and conduct the River Valley Radical Futures project—an effort to uncover the visions local prefigurative collectives have about a future beyond capitalism. Through a series of ten workshops with different collectives, we guided participants to envision a future that builds on the work they do today, 100 years beyond the fall of capitalism. Then, we synthesized participants’ responses into an illustrated map, showing different visions of future towns that exist side by side, with diverse economies in relationship with one another. We engaged worker cooperatives, mutual aid networks, a housing cooperative, and people working towards local community land trusts. We also held a workshop at the Massachusetts Solidarity Economy annual gathering. We hoped this could support a more open local conversation about the social transformations participants are working towards, including both shared dreams and diverging ideas. In particular, we hoped it could open a dialogue between collectives and designers about how we could design for this transformation today.

We intended to facilitate one workshop per collective, gathering people who lead the organization forward to articulate their future vision together. In the end, each workshop was different. One workshop included about seven members from two different worker cooperatives that collaborate as part of a local worker cooperative network. Another involved two volunteer members of an organization, and no staff. A third was conducted in Spanish and engaged about 13 people, including organizers as well as the community they organize with. Overall, we reached out to at least 21 collectives and facilitated workshops with members of more than 12. I also worked with another Smith College faculty member, Juan Sebastian Ospina, Lecturer in Philosophy, to facilitate a two-day visioning workshop for faculty from local colleges and universities.

Research assistants and I invited collectives to participate that we considered to be prefiguring a future without capitalism, and that were diverse across a variety of factors: location up and down the Connecticut river in Massachusetts, class, race, and type of prefigurative project and/or post-capitalist vision. It was important to us to include collectives from both sides of the “tofu curtain”, a nickname for a socioeconomic divide somewhere between Hampshire and Hampden Counties. Historically, it has been common to find post-capitalist experiments like worker cooperatives north of this divide, but less common to the south in Holyoke and Springfield, where there is more class and race diversity. Collectives like Wellspring, the Valley Alliance for Land Equity, and the Pioneer Valley Workers Center are intentional about crossing this divide to organize and provide services in these areas. We got to know collectives through slow networking over the course of a couple of years. We attended events like the Massachusetts Solidarity Economy Gathering and asked each new acquaintance to introduce us to other collectives they thought we should include.

Participants came into the project for multiple reasons. Many expressed that the project felt like a fun and hopeful exercise, a rare opportunity to talk with those they organize with about the future they are working towards. One participant said that the workshop felt worth their time because they’re inspired by mystical Jewish perspectives and leaders like adrienne maree brown to “live into” the world we need: “I believe that the work of imagining [and] visioning… gets us closer towards the material of those visions. This project feels so aligned with that understanding, for me. We get closer to the world we need by imagining that world and by… breathing into that world and embodying in that world”. Some participants were invited to participate by other members of a collective they work with, and may have been motivated to support that person or the group itself. We also communicated that the goal of the workshops was to create a map that would be shared publicly, so collectives may have wanted to include their name for publicity reasons. Some of the collectives we invited did not ultimately participate in a workshop. Many expressed interest in what we were doing. Some were prevented from participating due to leadership changes, conflict within the collective, or damaged trust with academic institutions, among other factors.

2.1. Workshop Flow

Each workshop was unique, tailored to the collective’s needs and the available time, but all followed a similar structure. We began by introducing the project and informing people that we intended to incorporate their work into a map that would be shared with the public. In earlier workshops, we discussed whether participants would like to be individually attributed or if they’d rather we use the name of their collectives. There was consensus to use collective names, so moving forward, we began stating this upfront.

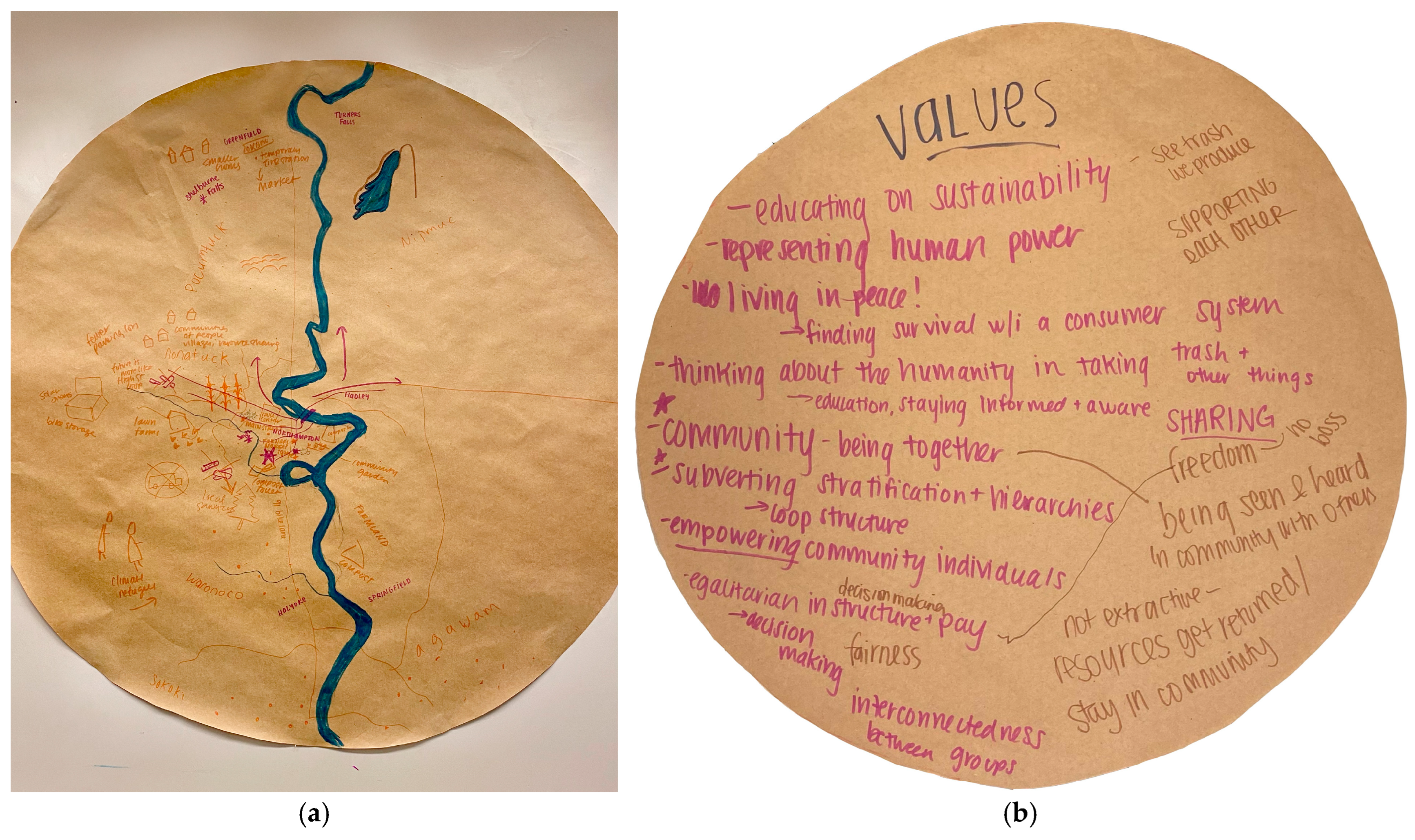

Then, we began by collaboratively telling a story of the past, present, and future of the Connecticut River valley, to orient ourselves to the geography of the area. In some workshops, we started by sharing a very brief history of the Valley. Student co-facilitators created a hand-drawn sketch of the area, with towns and landmarks called out. We discussed how the place was home to the Pocumtuc, Nonotuck, Woronoco, Agawam, Nipmuc, and Sokoki. We described the genocide that splintered many of these tribes and nations (the Nipmuc Nation is ongoing, and members of the others were driven to join other nearby nations). Then, we arrived in the present, where this land is called Massachusetts in the United States. We asked the participating collective to describe what makes the Valley home for them now, including places, buildings, and institutions (

Figure 1a). This helped to locate ourselves on the map and understand what places were familiar and important to the participants. Then, we asked about the work the collective does together in the present, and what values and priorities they are trying to enact through that work. As participants suggested ideas, we wrote down a list on a large piece of paper (

Figure 1b).

After exploring the past and present, we brought participants on a journey to a future 100 years beyond the fall of capitalism. We described the transition: “We’re seeing that we don’t call this land the United States anymore. We’re flying over the river, and we see towns and communities organized in different ways. Each has different systems, different ways of producing the things they need, sharing and trading, and different ways of living. Just as we often go from one town to another now, people travel and have relationships between places”. Then, we asked what had happened to the places we discussed earlier that are familiar to the participants today. This helped us locate ourselves in the future.

As the workshop continued, we asked participants to combine into small groups of 2–3 people. We distributed a mind map template (

Figure 2) to each group and asked them to use it to imagine what the future place would be like in more detail. We asked groups to choose one of the values we brainstormed together that are important to their work today. Groups wrote this value in the middle of the page, finishing the sentence “Our place in a world without capitalism prioritizes __”. Then, questions in each corner of the template prompted participants to consider: “In a place without private property ownership, how do people access land to live on?”, “In a place without exploitative labor, is there electricity, medical technology, or digital technology? How are these things produced? How do we communicate and share skills?”, “In a place without bosses or wage work, how is labor organized to produce the things we need? Who does what?”, and “In a place without capitalist profits or markets, how are resources distributed? How do people get the things they need?” We gave groups about 10–15 min to make notes on the mindmap, emphasizing that they could jump from question to question. If participants were stuck, we encouraged them to consider the priority in the middle of the page. We told participants that this mindmap should not be a perfect world, but simply a future that prioritizes the idea they’ve chosen, including both positive and negative implications.

After brainstorming on these questions, we asked groups to choose one aspect of the future place they had envisioned and use markers and paper to draw a scene showing how it looks (

Figure 3a,b). Groups drew people working together on farms and construction projects, people grilling and picnicking together, music notes, meetings, solar panels, distribution centers with free food and tool sharing, accessible hospitals, shared and private homes of all shapes and sizes, and the reuse of existing buildings. Lastly, we gathered together and asked each smaller group to share about their discussion. When we had time, we also shared some drawings from other workshops and asked the full group how they thought their place in the valley would relate to others.

2.2. Workshop Analysis

After each workshop, I worked with research assistants to summarize what was created, using participants’ own language. First, we transcribed the recordings of the workshop discussions, and then reviewed the transcript alongside our notes, as well as the mind maps and drawings produced by participants. We summarized these materials into a short paragraph about the future place participants had envisioned. One summary read: “In this place, the means of production are held in commons. For example, we share land that can be used for foraging and gardening, and we share hydropower electricity generators and fablabs. Decisions are made collectively in decentralized, participatory governments—decisions about what work should be done, and how to use common resources. These governing bodies listen to the land before making decisions on its behalf, and assign work based on people’s skills and interests. People follow their passions when choosing where to plug in and support their community. Small farms produce different foods and share and trade with each other. Importing and exporting from and to other communities happens, but there are rules and regulations. Participatory governments use data to make informed decisions about importing and exporting. Overall, we use less resources and have less resource-intensive technologies. We prioritize recyclable and renewable materials, like hemp”.

In large workshops, summarizing the participants’ visions involved identifying patterns among different groups’ ideas and also noting any divergences. For example, in the workshop with the Pioneer Valley Workers Center, some groups spoke about how land would be divided equally between families to avoid jealousy. In contrast, other groups emphasized that “not everyone has the same thing. Some people have small houses, others have big ones. If you work more, you get a bigger house”. (from the summary we wrote). In these cases, we created multiple ‘places’ on the map near each other that embodied these differences.

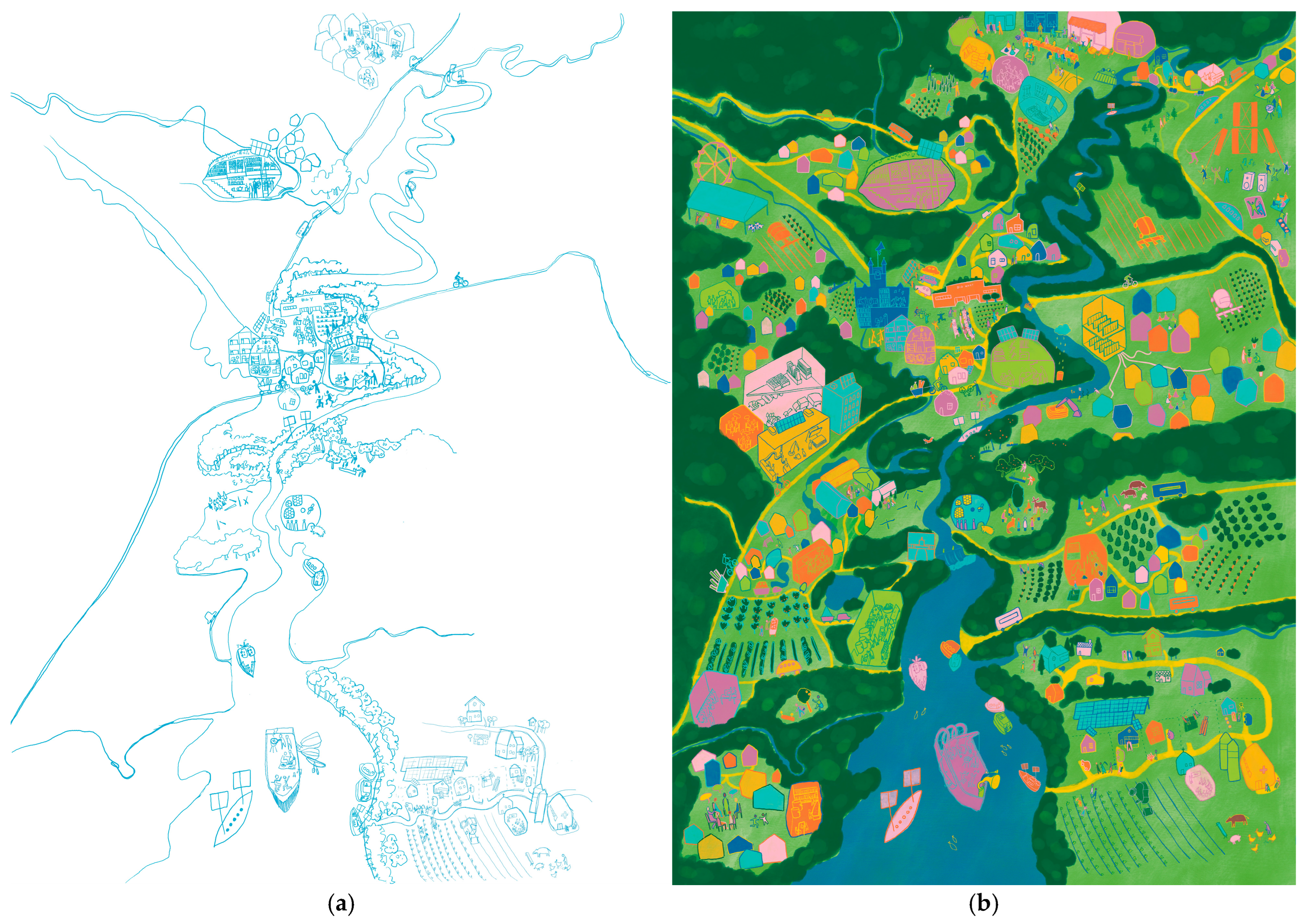

Once we had written the summary paragraph, research assistants and I worked to sketch ideas about how the places could be visualized within a map of the Connecticut River Valley. The illustration underwent multiple iterations, starting with an evolving sketch used in workshops to gather feedback (

Figure 4a), and then culminating in a final rendering (

Figure 4b). After the map was complete, it was printed on newsprint alongside an introduction to the project and the summaries of each collective’s vision (

Figure 5). The newsprint map was distributed to participating collectives to share with their members. It was also shared at a reception with a panel discussion between me and four workshop partners. Lastly, I was able to work with Smith College’s Design Thinking Initiative and the Sara Little Turnbull Foundation to commission five artists to create artifacts excavated from the vision of the map, and display them at three gallery exhibits up and down the valley.

The exhibits were popular among local residents, creating an opportunity to start a conversation about how we can design for social transformation today. When looking at the map, viewers often ask, “How will we get there”? During the process of creating the map’s vision, we set this question aside as a way to open space for a future that feels impossible. Now, with the vision in front of us, we can re-engage with the question about how to make it real. We can look at how collectives are already enacting this vision today through small, everyday decisions. We can consider how to embed this transformation into the design of our own processes and tools. During the first exhibit at A.P.E. Ltd. Gallery in Northampton, Massachusetts, I facilitated a workshop open to the public titled “Building Alternative Futures”. This workshop guided participants through a process of finding ways to enact a piece of the map’s vision that they want most in their daily lives. This resulted in ideas about riding to work on horseback, creating a clock based on a plant’s growing cycle, reorganizing classroom space to prioritize shared learning, and greeting people with eye contact and being curious about their beliefs.

3. Methods

This co-creation process was developed through a variety of methods, mindsets, and practices drawing from participatory design, or co-design, and speculative approaches. While speculative design and futures studies inspired our mindset and approach, this project diverged from speculative design practice in a few ways:

We produced an illustration. Typically, speculative designers produce three-dimensional models of objects that would exist within a transformed world, rather than illustrations of the world itself.

We distributed the map alongside explanatory text about the places it shows. This aligns more closely with speculative fiction, describing alternative worlds rather than showing them in physical form.

It is typically important for speculative design artifacts to stand alone, using only physical form to show that they exist within a transformed world. This requires a “process of mental interaction” from viewers, where they are surprised, challenged, and provoked to imagine their own version of the world that exists around the artifact. These speculative artifacts “are triggers that can help us construct in our minds a world shaped by different ideals, values, and beliefs to our own, better or worse, that we can entertain and reflect on” [

16] (p. 91). These are qualities I hope to bring into ongoing collaborative design efforts with prefigurative collectives, where they have the potential to challenge and provoke imagination for collective members as well as public witnesses. However, for this preliminary step, it was necessary to show the visions of participating collectives in a more accessible way.

In framing the process, we sought to create space for participants to reflect honestly and openly on a variety of post-capitalist visions, and to express them in tangible and material forms so that others could see and react to them. We also aimed to push participants’ imagination beyond the 5–10 year horizon that typically has our attention, towards a longer-term, fundamental social transformation. We structured the process around three key elements: the map, the workshop, and the mind map template.

3.1. The Map

In design fields, prototype models are often created to test forms of consumer products, typefaces, graphic layouts, digital tools, and even buildings and cities. The purpose of a prototype is to improve an idea through collaborative iteration; to allow different people to see and interact with an idea in the real world as a way to understand more about what works and doesn’t work about it [

24]. In this project, we used the map as an iterative prototype of a future world– something that showed abstract ideas in material form to allow others to see and respond to it, and to provoke conversations about what we want the future to be like. We presented the map not as a fixed proposal, but as something we hoped people would respond to.

Prototypes function as boundary objects [

25] by creating shared meaning between social worlds, across professional languages and different competences. The map functioned as a boundary object because it allowed multiple collectives to participate and to add their own ideas. They may not have been in the same room with other collectives, but they can see their ideas on the map and respond to them. For example, Oxbow Design Build Coop imagined the Big Y grocery store in their drawing, reused as a community space. Later, other participants saw “Big Y” and wondered why the grocery brand name was on the map. They suggested updated names in line with Oxbow Design Build’s vision of re-use: “Big Why?” Or “Big Us”. We showed the map sketch in progress, or drawings made by other participants, in each workshop so that we could discuss the relationships they imagined between areas.

The map illustrates various economic visions, each represented by a different town along the Connecticut River. This brings together two ideas, from futures studies and Arturo Escobar’s description of the pluriverse. Futurists often promote the idea of plural future possibilities, imagined as alternative worlds or realities [

26,

27]. Even as this mindset encourages a broad view of possible future outcomes, it also tends to produce each possibility as a totalizing vision of a future world, where one dominant system influences the globe. In contrast, Arturo Escobar describes the pluriverse as the idea that the world already encompasses multiple realities within a single moment, across different people and places [

6]. In the words of the Zapatistas, the pluriverse is “a world in which many worlds fit”, where many different ways of being coexist in relationship with each other. While some futures projects open space to imagine a new universal global system that replaces the one we know today, the idea of the pluriverse offers an alternative path that challenges our conception of modernity, progress, and colonization. This is why we departed from typical futurist frameworks that show multiple alternative visions side by side, and instead showed visions coexisting across physical space on the map.

Lastly, the map’s setting was important in grounding the imagined future in a geographical and historical context. The idea of producing a local map was conceived during a Community Economies in Action retreat hosted by Bianca Elzenbaumer, Kate Rich, and Flora Mammana. The map project discussed here was inspired by conversations with retreat participants while gazing out over the Lagarina Valley and considering the similarities and differences to our little valley back home. In particular, a collaborator, Eleni Andris, helped frame the project and came up with the idea to lay out futures in geographical space. At the end of the trip, I saw Elzenbaumer’s

Vallagarina 2060 map [

28], illustrating a Lagarina Valley full of commoning projects, alongside a description of plural futures and community economies. Kicking off the project back at home, we set the map in the Connecticut River Valley to connect present local collectives with others who have worked against capitalism over time.

3.2. The Workshop

The approach we followed stems from a legacy of participatory design, also known as co-design. This field investigates how to design

with the people who are most impacted by a technology, product, space, system, service, etc. Participatory designers assume that each person has expertise in their own lived experiences, and that everyone has the capacity to be creative and curious about the world around them. They also understand that the process of designing together requires active reflection as well as particular skills and time commitments. The practice of participatory design involves scaffolding this process to support mutual learning and collaborative decision making [

29,

30]. Workshops are a common tool to scaffold an interaction to “support collaborative enquiry” [

31]. While workshops in other contexts may be considered a place to teach a skill, participatory design workshops involve doing design work together, using design games and activities to foster collaboration.

In this project, we utilized workshops as spaces for prefigurative collectives to gather and explore the future vision that could arise from their current work. It was in workshops that we collaboratively generated the illustrated map of the future beyond capitalism. We envisioned each workshop as a closed space for a collective that already works together. We were ambivalent about the size of the workshops—we told collectives that even two participants would be enough. This was all done to create a safe and accepting environment for participants to explore their visions, while also investigating how those visions interact with those of other collective members.

3.3. The Mindmap Template

The mindmap template was a key structuring element of the workshop. The template encouraged participants to choose one value or priority, and then extrapolate from there to respond to questions that prompted transformations from capitalism. This approach builds on the “futures wheel” used in futures studies and speculative design. It served as the singular point in the workshop where we shared a definition of capitalism and framed transformational questions that built on prefigurative political strategy.

The “futures wheel” was invented by Jerome C. Glenn in 1971, who defined it as “a way of organizing thinking and questioning about the future—a kind of structured brainstorming” [

32]. This traditional structure involved placing a trend, event, or decision at the center of the wheel, and expanding from there in layers—first to the direct results of the event, and then to the consequences of those results. Our version specifically frames the trend, event, or decision as a “chosen priority” for this future’s economic system. It prompts results of that priority with specific questions about an economic transformation from capitalism.

While we began each workshop by brainstorming a list of values and priorities together, the mind map template only had space for participants to choose one priority from this list. We explained that this did not mean any future would actually have only one priority, but that it was a conceptual tool to ease the generation of future possibilities.

The prompts on the page were similar across workshops, but shifted over time. Early on, the prompts were only generative, for example, “How do people access land to live on?” Later, we added the language about negating the status quo: “In a place without private property ownership, how do people access land to live on”? This change came from our goal to support transformative visions, beyond additive reforms. It was inspired by a theme in scholarship about prefigurative politics. Activist-scholar Ethan Miller suggests that “it is both possible and necessary to oppose and compose simultaneously” and that “the task… must be something like creative critique or critical creation” [

33] (pp. 221–222). Anthropologist Marianne Maeckelbergh points out that “this prefigurative strategy requires at least two steps that are carried out simultaneously. One is the step of challenging and confronting current political structures and the other is constructing alternative structures to take their place. If both are not done simultaneously then neither is of any use” [

34] (p. 14). Since a prefigurative approach is about building a transformed world, it requires us to go beyond surface-level reform that merely builds upon existing systems. Instead, we need to start from an understanding of what systems or priorities we want to remove from the world, and then imagine what could take their place.

Each prompt targeted different fundamental aspects of capitalism in a way that is grounded in the material world, bridging the gap between theoretical critiques of the system and the everyday experiences of participants. In part, this was informed by the “Capitalism characteristics” defined by the Center for Popular Economics under Emily Kawano’s leadership, which research assistants and I then learned from Kawano at multiple events [

35]. These characteristics include private ownership of the means of production and wage labor (which create an inherent class struggle), as well as profit maximization as the top priority, commodity production (producing things for sale) and market exchange. We created mind map questions by grounding these concepts in participants’ daily lives.

4. Outcomes and Impacts

The goal of this project was to begin a conversation with local prefigurative collectives about how their work today is building towards a future beyond capitalism– how it goes beyond solving immediate problems, towards a foundational transformation. This is considered to be a first step towards collaboratively designing everyday tools with these collectives to use in the present that envision and perform that transformed future. Ultimately, the workshops succeeded in getting participants to articulate transformative shifts. They also opened conversations about designing for this transformed future today in a way that did not feel possible before the project. These impacts were different for each participant, depending on how much they had previously considered the idea of a post-capitalist future. The project also raised questions about the risks of sharing transformative visions, which may interfere with building diverse coalitions with those who do not want a post-capitalist future.

The workshops successfully enabled participants to articulate transformative shifts. In describing how to evaluate whether a political strategy is “pushing [an] anti-capitalist stance beyond the dominant ontologies”, Arturo Escobar suggests one could consider the question, “What habitual forms of knowing, being and doing does a given strategy contribute to challenging, destabilizing or transforming? For instance, does the strategy or practice in question help us in the journey of de-individualization and towards re-communalization? Does it contribute to bringing about more local forms of economy that might, in turn, provide elements for designing infrastructures for an ethics of interexistence and the deep acceptance of radical difference?” [

36] (pp. xxvi-ii). This can serve as evaluation criteria for the project. What forms of knowing, being, and doing were participants able to recognize and think beyond? What challenges kept us stuck on certain assumptions?

These were a few commonly envisioned transformations:

Under capitalism, labor is directed by private businesses producing things to be sold on the market, seeking what Karl Marx calls “exchange value” [

37]. In many of our workshops, participants envisioned a transformation towards labor that is determined by community need, or “use value”. Some groups referred to this transformation abstractly, such as “All contribute freely…, taking turns stepping up to community needs” (Pedal People) or even quoting Marx, “To each according to their need from each according to their ability”(People’s Medicine Project, Sirius Community) Others get specific about how they envision this happening. “A database sharing platform is required to broadcast what work needs doing and sign up for available work”, or “Smaller assemblies where people discuss what they need, send delegates to larger regional assemblies” (Solidarity Economy MA).

Under capitalism, individuals can privately own the means of production. For example, land can be owned by a private company to grow produce, which means that neighbors cannot grow their own food on that land, and must buy produce from the company at the store. In workshops, groups envisioned a transformation towards the commons, where people would be able to produce what they need using common resources. The commons participants spoke about included “renewable resources (hydropower and energy production), forests, forest management, farmland, infrastructure” (Oxbow Design Build Coop), “everything needed to sustain community needs: food, water, land, conservation land, shelter, bikes, boats, tools, water resources, managed by community of cooperatives” (Pedal People), or a “distribution center warehouse where we hold and share resources”. (Solidarity Economy MA) Groups spoke about how these resources held in common would be governed by “collective agreement” instead of ownership (People’s Medicine Project), “more direct collective decision making, representation in leadership”, and “coop owned and democratically shared” (Wellspring).

There were also some moments that showed how participants were caught up in capitalist forms of knowing, being, and doing, even as they imagined beyond capitalism:

The Pioneer Valley Workers Center organizes with people who came to the United States as low-wage immigrant workers. While collaborating on putting the workshop together, a leader of the organization emphasized that some of the participants came to the United States in search of the dream promised by U.S. capitalism, so a vision of a world without capitalism may be at odds with their worldview. In this workshop, the organization’s leaders facilitated a section using the “Tree of problems”, a framework that shows challenges participants feel in their own lives as leaves on a tree (e.g., harassment from their boss), and connects these leaves to the roots, the systemic reasons why these things happen. This helped to introduce why we were envisioning a future without capitalism. In the workshop, some participants pushed for transformation towards “solidarity” and a “united collective”, for example “We distribute resources in line with mutual support for our goals—health is a right, as is caring for animals, working the land”. and “Resources have to be equally distributed to all to avoid envy… if there are some resources on one side, we must consider the others and show solidarity so that no one is left behind”. Others aligned with the American Dream as the organization leader had predicted. One participant said that they envision a future where “everyone has their own comforts, their own house, their own car”. Another emphasized that people should have the freedom to work more if they want a bigger house: “[In my drawing,] there is a small house, a medium one, and a bigger one, because I believe that everyone can have their own house, but by merit. We can’t have everything equal, because if someone works more, they deserve more”. These visions may diverge from the solidarity-based dream created by others. Still, they differ from capitalist ways of being that prioritize the interests of owners over those of workers. This last participant articulated that “having more” should be dependent on “working more”. This may be a common narrative under capitalism, but in reality, capitalism benefits those with a higher net worth, which is not the same as the people who work the hardest or the most hours.

Among all participating collectives, many envisioned labor being assigned based on “genuine interests”, “unique gift”, “passion”, or “heart-centered motivation” of the worker. While this idea of labor as passion may challenge aspects of capitalism, such as the estrangement of workers from their labor, it also aligns with a capitalist perspective that views work as a means of self-actualization.

Another trend in responses was the vision that people receive what they need, and do not have to work. This vision challenges the capitalist ideal of endless growth and rejects the idea that people’s worthiness is defined by their labor. However, it also frames people as capitalist consumers who receive what they need rather than creating it. For example, one participant said: “Everyone has a basic income so doesn’t HAVE to do anything. All labor is by choice”. Other participants from this collective imagined that there is “local, renewable electricity” and “an internet that prioritizes humans and connection”, two ideas that involve the labor-intensive work of creating and maintaining computers and internet hardware. (Sirius Community).

Overall, the exercise provided a space to grapple with the ways in which we are all entangled with capitalism and to explore different ways of knowing, being, and doing. We did not have time in the workshop to critique the ways we may be stuck on capitalist ideas, as I have done above. Evaluation and discussion could be the next step with collectives, where we could use the map and its stories to examine participants’ visions and think together about how they may be entangled with capitalist ideas. This could be a way to support participants in further developing their visions, and in gaining flexibility to make conscious choices about the transformations they desire.

Beyond creating space to articulate transformative shifts, the workshops also opened conversations about designing for a transformed future today in a way that did not feel possible before the project. When I proposed the River Valley Radical Futures exhibit to a local gallery, they spontaneously asked if I could facilitate a workshop on designing for this future in the present moment. This was exactly where I hoped the project could go next. Later, a project partner, a participant from Stone Soup Cafe, shared that their organization’s board has been designing a new space for their community kitchen, and wondered if I could consult with them on how it could embody their post-capitalist vision. These were conversations that were difficult to begin before the project.

The project also showed that imagining the future together in this way can be a difficult process. It usually took at least four months, if not more than a year, for a participating collective to dedicate time to a workshop, even as they expressed their excitement about the project. Sometimes, after putting in so much effort to set up the time, only a couple of collective members or volunteers would attend the workshop. Many other collectives did not ultimately participate after we initiated the conversation with them. Once workshop participants were in the room, we usually had a lot of fun imagining together. Sometimes, participants expressed the mental difficulty of the task to imagine something beyond the systems around us today. One workshop group resisted the proposed activities for about an hour before settling into playful imagination. Overall, it seemed that collectives were avoiding the process we proposed, even though they also wanted to participate. I cannot be sure of all of the reasons behind this– it could be due to our approach, or to the idea of imagining the future itself. After the workshop in which participants resisted the activities, our partner who hosted us remarked that it must be an illustration of how uncomfortable we all are in envisioning the future. They said, “It’s challenging enough to plan for the next few months, let alone 400 years in the future”. Working through this paralysis usually involved letting people know we were only imagining one possible future, not predicting or planning what would happen. The structure we provided with the mindmap and choosing a singular priority also typically seemed like a relief to participants, though some rejected the idea of choosing one priority. It was clear that the transformation to a post-capitalist future meant a lot to those who participated in the project, and giving shape to the vision could be paralyzing and frustrating.

Beyond the difficulty of going through the effort to visualize possible post-capitalist futures, the project also raised questions about the risks of sharing transformative visions, which may interfere with building diverse coalitions with those who do not want a post-capitalist future, or who have different visions about what it could look like. In one workshop, a participant described an exercise they learned from sociocracy, a collective governance system. The exercise involves discussing the “mission, vision, and aims” of the work a collective is doing together. This participant said that while the mission and vision involve broad ideas like “We believe housing is a right and we want to end homelessness”, the aims are concrete, like “we’re running this shelter in Greenfield”. The participant said, “As long as the aims, the specific projects, are things that people can find alignment on… it doesn’t matter what we see as the super long goal”. This participant is saying that people can work together in a collective, even if they don’t agree on a shared vision. In this situation, would it endanger the working relationship between collective members if they discuss their visions and see that they are very different? If so, is there value in communicating what we’re working towards that outweighs that risk? In a panel discussion at the end of the project, I raised some of these questions. A panelist (another project participant) said, “I think of all of the work that I engage in as transformational, but the way I talk about it sometimes is transformational and sometimes it’s not. When we started out, we talked about worker-owned businesses called cooperatives but we never talked about solidarity economy. We never, and still rarely, ever say anything about it being a post-capitalist framework. Like, why alienate people? People are happy to support worker co-ops. That sounds almost as American as apple pie, right?” Others shared multiple perspectives on this kind of “code switching”, explaining how it is much easier to gather public support and engagement by starting from where people are and what we share, rather than an ideological vision. This concern about alienating potential supporters and opening up disagreement among collective members helps me understand at least one reason behind people’s hesitancy to share their transformative visions with one another.

While imagining the future together did achieve our goals of illustrating visions of transformation and starting the conversation about designing for this future today, it might be possible to get to the same place in a way that is less paralyzing and fraught, and more focused. Instead of envisioning futures, we could consider how we frame design prompts. One of my favorite examples of designers working within prefigurative politics is Carl DiSalvo’s work with the foraging organization Concrete Jungle. DiSalvo describes foraging as “a prototypical postcapitalist practice” that “offers an alternative model of exchange, while also exemplifying an alternative model of democracy” [

38] (p. 73). Similar to the practice I’ve set out, combining speculative design with the design of useful tools for everyday prefigurative practices, DiSalvo says he is interested in creating “devices of inquiry” which support the work of foraging and also “serve to query possible futures” [

38] (p. 71), [

39,

40]. To create these devices of inquiry, the design team (which included partners from Concrete Jungle) reframes their guiding questions, for example from “Where is the forage-able fruit?”, which is the practical question Concrete Jungle was facing as an organization, to “How might this representation [of the locations of forageable fruit] enable and participate in the work of governing this commons?” [

38] (p. 87). While DiSalvo speaks about “querying possible futures” through the devices the design team creates, they never visualized a future as part of the design process. They never answered the question about what a world that prioritizes the commons might look like. Instead, they addressed the practical problem at hand with a clear political commitment to commoning.

This aligns with Shana Agid’s focus on a “problem-setting” process that is reimagined through the lens of Paolo Freire’s concept of “problem-posing” [

41,

42,

43]. Agid proposes that ‘problem-setting’ is a deeply political component of design processes and the contexts in which designers and participants work” [

41] (p. 116). People may have “different understandings of ‘ideal’ worlds” which “are often under-theorized or un-discussed” [

41] (p. 119), [

44]. This is the problem I was running into when attempting to design tools and materials with prefigurative collectives– that when collectives gather around a practical aim, they may have a shared conception of working towards an ‘ideal’ world, while conceptualizing it in many different ways. Agid describes working with the abolitionist organization Critical Resistance, which seeks to abolish the prison-industrial complex. Critical Resistance is a deeply purposeful organization, but it does not have one shared vision of the future in mind. Instead, they anchor their work to a critique of the prison industrial complex, and they set “parameters of acceptable and legitimate action to take in relation to it” [

41] (p. 119). Working in a situated, collective way, they used Paolo Freire’s “problem-posing” to “name the things of the situation and place ‘the problem’ and what might be done about it in socio-historical and relational context” [

41] (p. 119). This is also what DiSalvo’s design team was doing by framing the fruit mapping project around “governing the commons”: bringing a socio-historical and political context around capitalist enclosures and commoning into a project about mapping fruit trees. In Shana Agid’s case, the Critical Resistance group reframed the function of policing in a historical and political context, using Rachel Herzing’s language, policing as “armed protection of state interests”. They asked, “What might it mean to design for ‘freedom’ or ‘well-being’ instead of against crime?” [

41] (p. 121). This problem-posing process is similar to our process of envisioning a future beyond capitalism because it invites ideas about how social systems could be different, before designing solutions for the current moment. However, there are also differences. Envisioning the future requires participants to generate many ideas and details about how the world might look different. In contrast, problem-posing does not require this defined illustrative vision. It only requires a critical perspective on participants’ current reality. With “designing for freedom or well-being” in mind, the Critical Resistance team was able to respond to specific community needs that currently activate police involvement, like responding to emergencies, and collaboratively design ways to meet those needs without policing.

A few years after the collaboration Agid describes with Critical Resistance, the organization published a poster titled “Reformist reforms vs. abolitionist steps to end IMPRISONMENT” [

45]. This poster presents four questions viewers can use to determine whether a specific proposal is a “reformist reform” (a solution to a problem that, in the end, strengthens the foundation of the carceral system), or whether it is an “abolitionist step” (a prefigurative effort that works towards a fundamental systemic transformation). The questions are: “Does this reduce the number of people imprisoned, under surveillance, or under other forms of state control?”, “Does this reduce the reach of jails, prisons, and surveillance in our everyday lives?”, “Does this create resources and infrastructures that are steady, preventative, and accessible without police and prison guard contact?” and “Does this strengthen capacities to prevent or address harm and create processes for community accountability?” These questions provide an example of how we can be clear and targeted about what we do not want to reproduce, as well as generative about the alternative direction we want to take, while not necessarily spelling out what that vision might look like. For example, consider the question that asks if a proposal “strengthens capacities to prevent or address harm and creates processes for community accountability”. The clarity of the question sets “parameters of acceptable and legitimate action” [

41] and also provides a clear frame to work within, which soothes imagination paralysis. At the same time, the question’s openness allows room for a diversity of visions and actions in response.

Using problem framing instead of future visioning would not necessarily avoid conflict around long-term political visions, but it could focus that conflict on the most important parameters of collective action, rather than ideas that arise while envisioning the future. Could a focus on problem framing allow collective members to define what they do agree on about the current socio-historical and political context, while leaving space for many possible futures to emerge?

Either way, expressing and exploring a transformative project could exclude people who do not want such a transformation. However, it seems that these conflicts will arise if a collective is interested in prefiguration, even if they are not explicitly discussed. Think back to the New York mutual aid network, where members disagreed about where to get groceries and whether to take fiscal sponsorship. Conflicts about the visions we are working towards permeate all of those practical questions. Pretending conflict doesn’t exist seems to take power away from the prefigurative effort, because without a clear reason, it will always make more sense to do things in a normative way aligned with the dominant system. If members of a prefigurative collective expressed their visions and political frameworks clearly, even if they conflict with each other, how would that impact their work together? Would it cause fewer people to join the collective? How would it impact decision making?

Beyond these risks, there are many potential rewards to clearly framing the transformation a collective is working towards, and embedding it into the everyday tools they use. Collectives already create relationships, systems, language, visuals, technologies, and physical and digital tools and materials that defy normative ways of doing things in favor of alternative ways that envision transformed social systems. What if we could use a speculative design approach to co-design these artifacts, to simultaneously meet people’s needs in the current moment, and also perform an alternative vision that challenges assumed social structures? I imagine multiple impacts:

Everyday tools embedded with a transformative vision could serve as a constant reminder to those working with the collective about what they are working towards, strengthening their commitment to the vision. Prefiguration is a consistent effort to refuse normative ways of doing things and to choose to do them differently. A strong commitment to the vision, along with the feeling that others share this commitment, is a powerful tool in that effort.

A speculative design approach could convey the collective’s vision for outsiders. Speculative design involves a unique metric of success: that an object appears to be strange or transformed from the world we know. While this does carry the risk of alienating viewers, it also carries the power to express the vision and invite viewers into the world the prefigurative collective has imagined. For example, one could think of the Black Panther Party’s uniform. The black beret, afro, sunglasses, black leather jacket, and openly carried firearm performed their vision of Black Power, pride, self-determination, and liberation [

46].

Going through a collaborative design process as a group to design something that evokes the collective’s future vision would create a site where collectives must explore that vision together, including ways in which their ideas diverge. This could strengthen participants’ commitment to the parts of the vision they share, and could also create space for ongoing conversation about the ways they disagree.

Could a speculative design approach be used within prefigurative efforts to design tools that meet organizational needs while also performing social transformation? Such tools could strengthen members’ resolve to refuse normative practices, clearly express their visions to outsiders, and create collaborative spaces where political commitments can be articulated and negotiated together. However, this is a challenging creative exercise. It requires the capacity to engage with diverse visions among collective members and to navigate tensions between incremental and radical change. By guiding local collectives to envision a future 100 years beyond the fall of capitalism, we were able to surface the transformations participants sought and open conversations about how to design for these futures in the present. The process was also fraught: participants struggled with paralysis around imagining the future, and concerns that articulating long-term visions could alienate people who envision something different. Considering these challenges, there may be alternative routes to designing together. For example, rather than envisioning futures, designers and collectives could frame design problems by placing them in a socio-historical and political context. This could enable a design process that is focused on social transformation, while also remaining open to many possible future outcomes.