1. Introduction

This study addresses social change in higher education caused by the widespread adoption of generative Artificial Intelligence. Technological innovations, including AI, are bringing breakthroughs to higher education. Despite the need for critical scrutiny and academic debate about the ethical implications of AI, students and academic staff are already using GenAI tools [

1]. AI-generated content (text, images, audio, and video) has brought unprecedented changes to higher education [

2]. In the paper [

3], most professors reported engaging in AI but not integrating it.

Meanwhile, 41% of students used AI in explicitly prohibited ways [

3]. Therefore, there is no reason to doubt that students and academic staff will continue to use GenAI in the future [

1]. This fact means that academic staff will need new, effective approaches, models, policies, guidelines, and general guidance. Traditional higher education pedagogy will lose its didactic effectiveness, just as essays written by students “independently” with the help of AI have already lost their didactic effectiveness. Existing approaches, models, policies, and teaching guidelines will be adjusted and developed [

2].

At the same time, some authors believe that the use of AI in education is still in its early stages of development [

4]. However, they consider integrating AI and robotics into higher education, including student feedback [

4]. The paper [

5] shows that the top 10 most cited global publications on education issues were AI-related in 2023: these articles’ citations ranged from 699 to 1703. These highly cited publications relate to the higher education system [

5].

The paper continues to study the intersection of higher education sustainability, AI tools, and higher education services [

5,

6,

7]. It is well known that higher education plays a significant role in sustainable development in three sectors of society [

8].

Recently, higher education has become very relevant due to the intensive use of AI [

5]. AI tools have rapidly adapted and improved educational programs in the last few years, tailoring them to students’ needs. AI helps academic staff collect and analyze current data, identify difficulties in mastering educational material, quickly record students’ lagging behind planned results, and manage the educational process [

2]. AI tools make creating interactive learning platforms much easier for academic staff. Students also use AI for personal and educational purposes [

1,

3]. Ignoring students to use AI in the pedagogical process without regular supervision can lead to a dramatic decline in the quality of higher education. So, our study focused on the intersection of AI with higher education. There is a paper close to our research [

9]. We of the paper [

9] stated the need to adjust the didactic theory in connection with the development and implementation of IT technologies.

The research gap is the lack of conceptual models describing AI as an active participant in educational services (uninvited assistant). Despite the increasingly active implementation of artificial intelligence (AI) in educational practice, there are no quantitative studies in the scientific literature confirming the regular use of AI by students as a basis for revising the traditional two-subject didactic model.

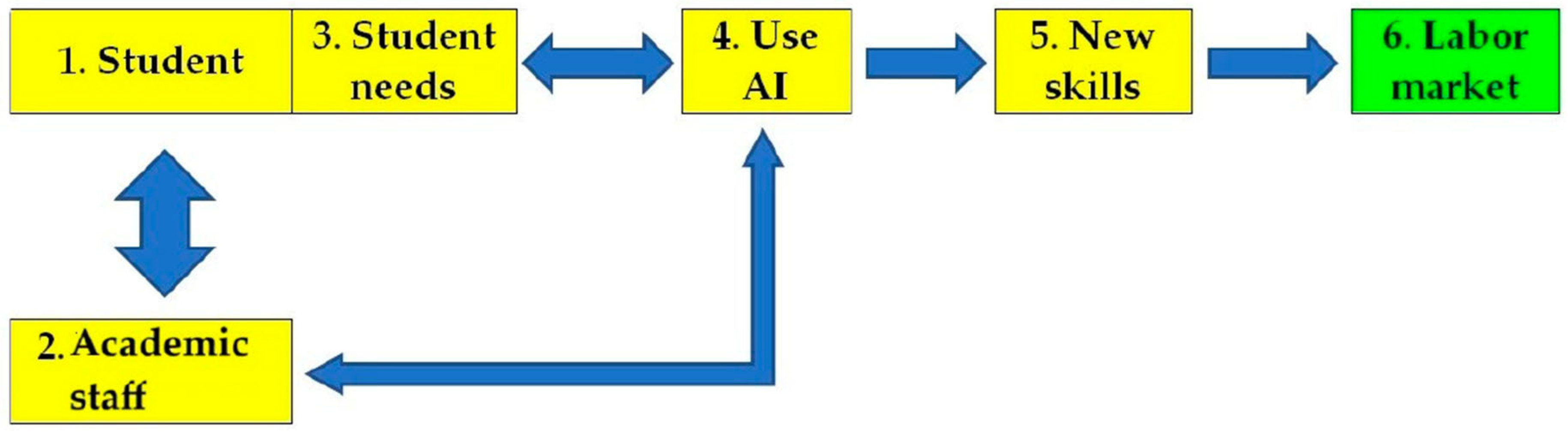

The study’s main aim was to check whether students’ regular use of AI tools leads to the formation of a new active participant in the system of higher education services.

To achieve this goal, we formulated and tested a conceptual assumption: students’ use of AI in the learning process could lead to the emergence of a third player in higher education services.

To achieve the research objective, we use bibliometric analysis and an empirical survey of students. Bibliometric analysis allows us to identify the evolution of academic discourse on artificial intelligence in higher education. The survey, in turn, records the real practices and perceptions of students from different countries. The combined use of these approaches ensures the testing of hypotheses at the discursive and applied levels. It forms the basis for developing a conceptual 3D model of the role of AI in educational services.

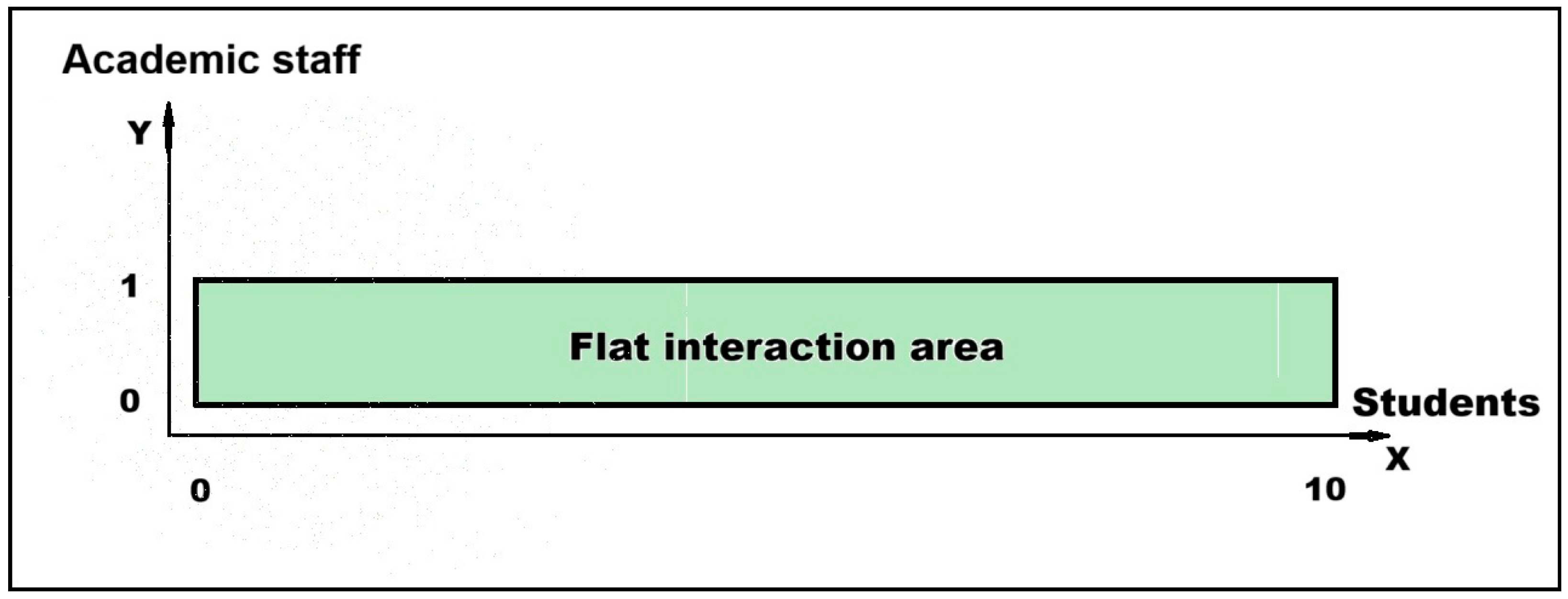

The conceptual assumption is based on pilot data and is subject to further verification on a broader empirical basis. Accepting the conceptual assumption means that the third player (uninvited assistant) may change the higher education services model from flat (2D, X: Y) to three-dimensional (3D, X:Y:Z). This fact does not mean that AI is attributed to properties it does not possess. It is accepted that the third player has appeared in the higher education services along the Z-axis. This third player should be considered only if at least one of the traditional market players regularly uses AI in the pedagogical process. By “regularity,” we mean the daily use of AI in the pedagogical process. This traditional player can be students (X-axis) and academic staff (Y-axis).

The study’s conceptual assumption was formulated as four separate hypotheses for empirical testing.

Hypothesis 1. The role of AI in higher education has changed in 2023, and AI has taken a central place in academic discourse.

Before 2023, academics perceived AI as a technological tool supporting educational applications. Academics began to imagine AI as a more developed and complex network in which “artificial intelligence” plays a much more central and dominant role from 2023.

This hypothesis aims to test whether there has been a shift in the perception of artificial intelligence in the academic community.

The remaining hypotheses are presented in a formal academic style with null (H0) and alternative (H1) statements.

Hypothesis 2.

H0: The proportion of students who need to use AI regularly in their learning equals zero (M(x) = 0.00%).

H1: The proportion of students who need to use AI regularly in their learning is greater than zero (M(x) > 0.00%).

This hypothesis tests whether students have a real demand for the everyday inclusion of AI tools in the learning process.

Hypothesis 3.

H0: The proportion of students who regularly use AI in their learning equals zero (M(x) = 0.00%).

H1: The proportion of students who regularly use AI in their learning is greater than zero (M(x) > 0.00%).

This hypothesis shows whether students actually use artificial intelligence in their learning activities on a daily basis or whether they limit their use to occasional activities.

Hypothesis 4.

H0: Students’ need for regular AI use in learning is equal to their actual use of AI (M(x1) − M(x2) = 0.00).

H1: Students’ need for regular AI use in learning is not equal to their actual use of AI (M(x1) − M(x2) ≠ 0.00).

This hypothesis identifies whether there is a discrepancy between students’ needs and their actual frequency of AI use. This outcome may indicate a mismatch between educational services and student needs.

The fundamental novelty lies in creating prerequisites for further developing the theory of subject–subject relations in didactics and the theory of educational services. As a result of verifying hypotheses, it was statistically proven that the number of students who regularly use AI in the learning process is greater than zero. The result of the study was the transformation of the subjective opinions of 1190 respondents into new scientific knowledge. For the first time, this new knowledge indicates the possibility of a new player appearing in the higher education services.

The study’s scientific contribution combines two methodological approaches: bibliometric analysis and empirical survey. This combination allowed us to simultaneously trace the evolution of academic discourse and identify real practices of students using AI. As a result, a comprehensive 3D model appeared, reflecting the role of AI as a new subject of educational services (an uninvited assistant) in the digital era.

The higher education services’ first hypothetical 3D model (X:Y:Z) was built based on empirical data. This qualitative model shows the fundamental possibility of considering higher educational services as a more complex structure. The new structure of the higher educational services can have three dimensions (X, Y, and Z). Preliminary shares of the axes (X, Y, and Z) in the 3D model are determined based on empirical and statistical data from universities in Eastern European countries. At this study stage, the 3D model is a conceptual assumption aimed at recording a shift in educational dynamics under the influence of AI.

The data in this paper has a significant predictive potential for a more detailed study of the theory and practice of using AI and its impact on society. Sooner or later, AI may become an active player in higher education services. Therefore, it is essential to study both the theory of services, particularly the higher education services, and the features of the practical application of Artificial Intelligence in higher education.

The results’ practical significance is in the prerequisites for further developing three-subject didactics. Ignoring the scientific fact that the regular use of AI by students in the learning process is greater than zero can lead to a dramatic decline in the quality of higher education.

Acceptance of the conceptual assumption about the possibility of the new player appearing in higher education services will contribute to the mobilization of pedagogical science. At least for higher education, the entire didactic theory should be adapted to the new reality. This is a grandiose task for pedagogical universities and Ministries of Education. Scientists and educators should solve the problem of effective pedagogical interaction in the three-dimensional (3D) model.

Next, these studies will help higher education institutions improve the quality management of higher education services. The organization of courses on the study of new didactics for the mass training academic staff is vital. The task at this stage may be to form a dominant role for academic staff in using AI in the pedagogical process.

Further, by accepting the new scientific fact, countries’ governments and university management can influence each of the three market players. At this stage, the task can be to manage educational institutions and higher education services better. At this stage, it becomes essential to develop legal and ethical standards of behavior in higher education services. The quality of management can be improved by adopting strong management decisions, technological restrictions, regulations, and other documents related to the use of AI.

2. Literature Review

The large body of contemporary research on the role of AI in higher education demonstrates a significant diversity of topics and approaches. However, a common thread unifying these publications is a gradual shift in emphasis: from perceiving AI as an auxiliary technological tool to recognizing it as an active player in transforming the academic community. At least three key areas can be identified in the literature:

- (1)

The didactic dimension (the changing nature of student-faculty interactions influenced by digital technologies);

- (2)

The institutional dimension (the impact of AI on quality management and university organizational models);

- (3)

The ethical and legal dimension (challenges to academic integrity, regulation, and trust in educational systems).

Considering these areas allows us not simply to list the results of previous research but to identify a systemic problem: the lack of a holistic model that would consider AI as a full-fledged participant in the educational process. These publications highlight the potential of AI to personalize learning, automate assessment, support teachers, and transform universities’ teaching practices and organizational models.

For example, a framework that combines game mechanics with AI-based personalization to improve learning outcomes in online environments was described in a paper [

10]. We explained how AI helps organize pedagogical interactions between teachers and students. A group of scientists evaluated the performance of two large language models (LLMs): GPT-3.5 and GPT-4, on the Polish Medical Final Exam (MFE) [

11]. Thus, pedagogical interaction between teachers and students also occurs here. One of the first peer-reviewed journal articles on ChatGPT explored its relevance for assessment, learning, and teaching in higher education [

12]. The article’s concluding section presents recommendations for students, teachers, and institutions. The critical role of AI in personalizing learning experiences, improving the accessibility of education, and supporting teachers’ teaching methodologies is highlighted in [

13]. We draw attention to the issues related to academic misconduct, such as plagiarism and misuse of AI-generated content. This study covers teacher–student pedagogical interactions. In summary, papers [

10,

11,

12,

13] illustrate a wide range of issues at the intersection of AI and higher education.

The use of ChatGPT and other natural language processing technologies to improve the efficiency of academic writing and research was described in the paper [

14]. This review is focused on academic staff. Several scholars have studied AI-based chatbot technology, particularly GPT-4, to assess opportunities and risks in healthcare delivery and medical research [

15]. This study is of interest to scientists. The purpose of the survey of 1104 students from eight Eastern European universities was to determine whether students perceive the use of AI as a threat to the higher education system [

16]. This study is of interest to students and academic staff. It was shown that most students perceive ChatGPT as a valuable tool for improving their learning [

17]. It was shown that students have serious concerns about academic honesty. This study [

17] is explicitly focused on students. Thus, the papers [

14,

15,

16,

17] show that the results of AI research cover all target groups: students, scientists, and academic teachers.

The use of AI focuses on emerging trends, theoretical frameworks, and hardware platforms used to assess the impact on the sustainability of art education [

18]. The ideas are of critical importance for developers and educators. These ideas increase the level of understanding and engagement of students beyond current educational offerings. Thus, this work covers the pedagogical interaction between teacher and student. Moreover, this work already speaks about educational offerings that are a component of the education services [

19]. The following study of higher education services has a long history.

Some Hispanic-serving institutions use AI chatbot technology on their websites and the usability of this technology for accessing admissions information [

19]. This study is of interest to universities’ interactions with prospective students.

ChatGPT was asked to take a standardized test of economics knowledge administered in the United States [

20]. ChatGPT scored in the 91st percentile in microeconomics and the 99th percentile in macroeconomics compared to students taking the exam at the end of their course. This paper covers the pedagogical interaction between teacher and student regarding pedagogical qualimetry. Some researchers identified skills gaps between academic training in AI in French engineering and business schools on the one hand and labor market requirements on the other hand [

21]. The paper addresses both teachers and students in the process of pedagogical interaction.

The impact of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools on higher education and research in tourism and hospitality was studied in the paper [

22]. We showed that implementing GenAI in education can contribute to personalized learning, increase students’ technological competence, and create a more diverse and inclusive learning environment. Also, this study raises several ethical issues that have been explored in papers [

13,

17]. Finally, this study covers the pedagogical interaction between teacher and student.

The role of AI in changing the quality of knowledge and the learning process is discussed in the article [

23]. It is shown here that AI represents a significant step towards blurring the boundaries between formal and informal education. The following study critically examines ideas regarding using AI in education [

24]. This document contains essential advice for educators, university leaders, and governments.

Higher education does not exclude the traditional didactic process with two participants. For example, a special issue of the European Educational Research Journal [

25] presents a series of research papers in the EERA 27 network “Didactics—learning and teaching”. The essential focus in the study of learning and teaching processes are described in the article [

25]. One of the foci is educational (joint) actions and conversations in the classroom. Didactics is an established educational discipline in continental Europe [

26]. It is often found as subject-specific didactics, also called subject didactics: in Scandinavia, Germany, Switzerland, France, Spain, and other countries. Less often, it can be found as general didactics, including in the same countries. As a separate educational discipline, didactics does not exist in the United Kingdom, although some areas of didactics do exist: curriculum theory, instructional research, etc. [

26]. The EERA 27 network offers a space for dialogue on the multiple European research traditions for conceptualizing the relationships between learning, teaching and the content knowledge that shapes education and learning for new generations [

27].

The relationships between different categories for the analysis of joint actions of a teacher and students were examined [

28]. The interaction of two subjects: a teacher and a student, was studied in one of the recent papers [

29]. The methodology used to teach students a school research lesson was described [

30]. This example refers to the interaction of two subjects: a university teacher and a student. Here, the future teacher studies active interaction with a student. Information and communication technologies (ICT) are examined from the point of view of subject–object and subject–subject relations in the article [

31]. We note that ICT contributes to the study of music education. They enhance motivation, musical and technological thinking, critical thinking, creativity, musical practice and improvisation, and contribute to exciting, playful, enjoyable and stimulating learning [

32]. Also, the didactics of subject–subject relations using ICT is described in the article [

9]. At the same time, publications on subject–object relations continue to be encountered [

32]. Thus, papers [

9,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32] describe subject–subject and subject–object didactics.

A recent quantitative study examined the impact of internationalization practices on service quality and student loyalty in public universities in Malaysia [

33]. The study adds to the growing body of knowledge on student satisfaction, quality perception, internationalization of education and student mobility. Student satisfaction with higher education services was studied in Macedonia [

34]. Various aspects of pedagogical interactions between teachers and students in Eastern European universities are described in [

35,

36]. The service quality issue for prospective students using artificial intelligence was investigated in [

19]. Some challenges associated with higher education services in Eastern Europe are described in [

5]. Private higher education institutions in China have taken on the responsibility of meeting the needs of regional labor markets [

37]. The core content of educational services is to provide graduates with jobs in regional markets. An earlier study analyzed how university career services can transform and innovate [

38]. This study bridges the gap between universities and business by applying a well-developed theoretical framework of platform business models to universities. Papers [

39,

40] also focus on providing and using international higher education services.

These factors influence South African students’ satisfaction with the learning management system (LMS) [

41]. We argue that the quality of the LMS services increases students’ satisfaction with the LMS. If students’ expectations are not met, their satisfaction decreases. It is further argued that a statistically significant negative relationship exists between teacher–student relationships, peer networks, employability confidence, and intentions to drop out [

42]. Strong teacher–student relationships and satisfaction with support services, i.e., high service quality, positively impact the university’s social capital [

42].

Some studies examined the entrepreneurial competence of faculty in higher education [

43]. The entrepreneurial competence model of faculty assessed respondents’ competence in four critical areas of teacher training: pedagogical, social, personal, and professional. The results showed that social competence received the lowest score. This fact indicates possible problems in providing services to students and forming subject–subject relations [

43]. The introduction of AI in education is closely related to teachers’ readiness and professional development.

So, the interest of researchers in educational services has been maintained recently [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

Adopting AI in education is closely tied to teacher readiness and professional development [

44]. The article found that behavioral intention to adopt new teaching technologies depends heavily on leadership and professional standards, suggesting that strategic organizational culture must support successful AI integration. Meanwhile, research [

45] emphasized the need for ethical clarity in students’ use of AI tools, underscoring the importance of AI literacy and regulatory guidance.

Innovative teaching environments are increasingly shaped by immersive technologies such as virtual and augmented reality, which authors of [

46] identified as tools for enhancing learner engagement and marketing educational offerings. Similarly, the study [

47] explored how virtual learning became a critical driver of business education during COVID-19, with AI as the backbone for sustaining and scaling remote learning. The structural implications of AI-driven education also emerge in research [

48] on digital reform in the Philippines, where overcoming the middle-income trap requires systemic educational technology integration.

Institutional factors such as organizational climate and communication norms significantly impact the adoption of digital tools. It was highlighted that minimizing organizational silence is essential for enabling open discussion around AI adoption [

49]. In measuring quality in AI-enabled education, the investigation [

50] proposed a multidimensional approach that captures institutional, technological, and human factors. Further, we of the study [

51] identified AI as a strategic asset in open innovation processes and management, reinforcing its value beyond pedagogy into institutional development. Collaborative R&D between business and academia, explored in [

52], suggests that AI also facilitates knowledge transfer and innovation alignment.

It was explored AI’s role in solving educational problems through automation and personalization [

53], while other authors [

54,

55] emphasized its utility in combating financial fraud and shaping fintech-driven education. A new study revealed regional disparities in higher education financing in China [

56], pointing to the importance of AI in optimizing resource allocation. The relationship between education, financial literacy, and inclusion is examined, with AI offering scalable pathways for democratizing access [

57,

58]. As discussed, AI-driven behavior analytics are becoming integral in marketing strategies within the extended reality metaverse, adding new layers to how education is delivered, personalized, and sold [

59]. It also provided a bibliometric roadmap for how AI intersects with developing lifelong learning systems and sustainable development goals [

60]. Public perception and ethical considerations remain critical in shaping AI’s future in education. The following study outlined the range of public sentiments—fear, hope, and indifference—influencing AI acceptance [

61]. Some researchers emphasized the irreversible presence of AI in educational landscapes, demanding urgent ethical and policy adaptation [

62,

63].

So, AI also reshapes higher education’s financial, marketing, and access dimensions [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63].

From a strategic mission standpoint, universities are expanding their roles beyond teaching and research, particularly in crisis recovery roles where AI can play a transformative part [

64]. AI may also be identified as a strategic asset in open innovation processes and management [

51]. Another study further supported that AI can support impact reporting and social responsibility in higher education through standardized digital frameworks [

65]. In this context, the term “3D” reflects the fusion of digital intelligence, dynamic service delivery, and data-informed policy-making—a new structural model for higher education. We argued that lifelong learning, supported by AI, contributes to national innovation capacity [

66], while ref. [

67] emphasized the synergistic development of digital ecosystems and entrepreneurial education environments.

AI’s role is no longer confined to operational support; it is now embedded in curriculum design, resource allocation, student evaluation, and strategic planning. With applications ranging from quantum theory-based modeling [

68] to AI in healthcare diagnostics [

69], the education sector is learning from cross-industry innovation and applying it to build adaptable, intelligent education systems. The study investigates the digital economy’s transformative effect on public health systems, offering transferable methodologies for modeling AI-led transformation in educational services [

70]. The transformation of educational work environments during COVID-19 was analyzed, reinforcing AI’s utility in supporting flexible and remote educational delivery [

71]. Historical perspectives offer context on post-crisis education in Ukraine, identifying systemic issues that AI may address through tailored teaching solutions [

72].

Thus, recent studies examine issues of strategic management and implementation of innovations in higher education [

51,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72].

AI’s role in higher education is poised to expand even further, driving the development of lifelong learning systems [

60,

66], fostering entrepreneurial education environments [

43,

60,

67], and contributing to national innovation capacity [

66,

72]. The education sector draws inspiration from cross-industry innovation, applying advanced technologies like quantum theory-based modeling and AI in healthcare diagnostics to create adaptable, intelligent education systems [

68,

69]. This evolution underscores the need for proactive strategies and collaborative efforts to harness AI’s transformative potential, ensuring that higher education systems remain relevant, effective, and equitable in rapid technological advancement [

15,

17,

19,

20,

22,

53].

AI is rapidly transforming numerous sectors, and higher education is no exception. Its influence extends beyond operational support, increasingly shaping how universities function and deliver education [

64,

65]. From curriculum design and resource allocation to student evaluation and strategic planning, AI is becoming deeply embedded in the structural framework of higher education systems [

23,

70,

71]. This technological integration promises to revolutionize teaching methodologies, enhance learning experiences, and ultimately redefine the role of educational institutions in the 21st century [

10,

12,

32,

44].

The shift towards AI-driven higher education necessitates a comprehensive re-evaluation of traditional practices and the adoption of innovative approaches [

10,

62,

66]. This transformation involves embracing AI tools and addressing the challenges and opportunities they present. Factors such as teacher readiness [

44], ethical considerations [

13,

17,

22,

61,

63], public perception [

16,

61], and institutional adaptation [

51] play critical roles in determining the successful integration of AI into educational settings. As a result, universities are evolving to incorporate digital intelligence, dynamic service delivery, and data-informed policy-making, forging the new, “3D” structural model for higher education [

65].

Thus, an analysis of current research shows that scholars have accumulated significant data on the didactic, institutional, and ethical-legal aspects of AI implementation in higher education. They document individual effects or challenges, but fail to offer a comprehensive conceptual model capable of integrating student learning, academic staff activities, and the impact of digital technologies into a single framework. This gap underpins the relevance of our proposed transition from the traditional two-dimensional model of educational services to a three-dimensional (3D) model, where AI acts as a new active participant (an uninvited assistant). This formulation of the problem not only allows us to clarify the study’s theoretical framework but also provides a foundation for applied solutions in the field of quality management in higher education.

The literature review, therefore, provides a strong foundation for future bibliometric analysis of the evolving role of AI in higher education [

60]. It effectively outlines key themes and trends, highlighting the multifaceted impact of AI across teaching, institutional transformation, and ethics. A bibliometric analysis can systematically map and quantify this research landscape, offering an objective overview of the field’s development and complementing the qualitative insights of the literature review [

51,

64,

65].

3. Materials and Methods

This study is designed as descriptive-explanatory research at the intersection of higher education and digital technologies. It combines bibliometric analysis with a quantitative student survey to identify structural changes in higher education services caused by AI adoption. The empirical base includes data from Bulgaria, Kazakhstan, Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine. The cross-country scope (Bulgaria, Kazakhstan, Poland, Slovakia, Ukraine) was motivated by socio-cultural and economic diversity and the region’s sensitivity to digitalization [

5,

16].

The methods applied cover bibliometric analysis, statistical hypothesis testing (t-statistics, z-statistics), and primary survey data processing. These approaches allow us to test the conceptual assumption of AI as a “third player” (uninvited assistant) in higher education services.

The study is based on modern provisions of the theory of subject–subject relations in didactics and the theory of educational services. The conceptual approach consisted of an empirical analysis of student practices in Eastern European countries. The research plan included a study of the practical use of AI in the pedagogical process, examples of the interpretation of higher education as an educational service, and a theoretical basis for creating the new 3D model of higher education services.

The choice of Eastern European countries as the empirical base of the study was not accidental. The choice has a scientific justification presented in previous publications [

5,

16]. These works point to the specifics of the Eastern European higher education services market [

5] and national educational systems [

16]. Sensitivity to innovative technologies and current challenges of digitalization [

5,

16] allows us to accept this region as a pilot for analyzing the implementation of AI in higher education services.

3.1. Research Steps

The study included the following stages:

Preliminary study of scientific literature;

Formulation of hypotheses;

Development of research methodology;

Bibliometric analysis using standard methods (PRISMA);

Survey of students using an electronic questionnaire posted in the cloud service of the National Louis University;

Primary processing and graphical visualization of empirical data;

Calculation of statistical indicators using standard methods;

Testing of statistical hypotheses using standard methods (t-statistics).

The validity, relativity and reliability of the results were ensured as follows: methodological validity of the initial provisions; use of research methods adequate to their purpose, objectives, logic and scope; use of a reliable system, clear instructions and a simple user interface; absence of observer influence on the observed; professionalism and scientific rigor; representativeness and statistical significance of experimental data; impartiality of assessment during their processing and interpretation; consistency of conclusions.

3.2. Bibliometric Analysis

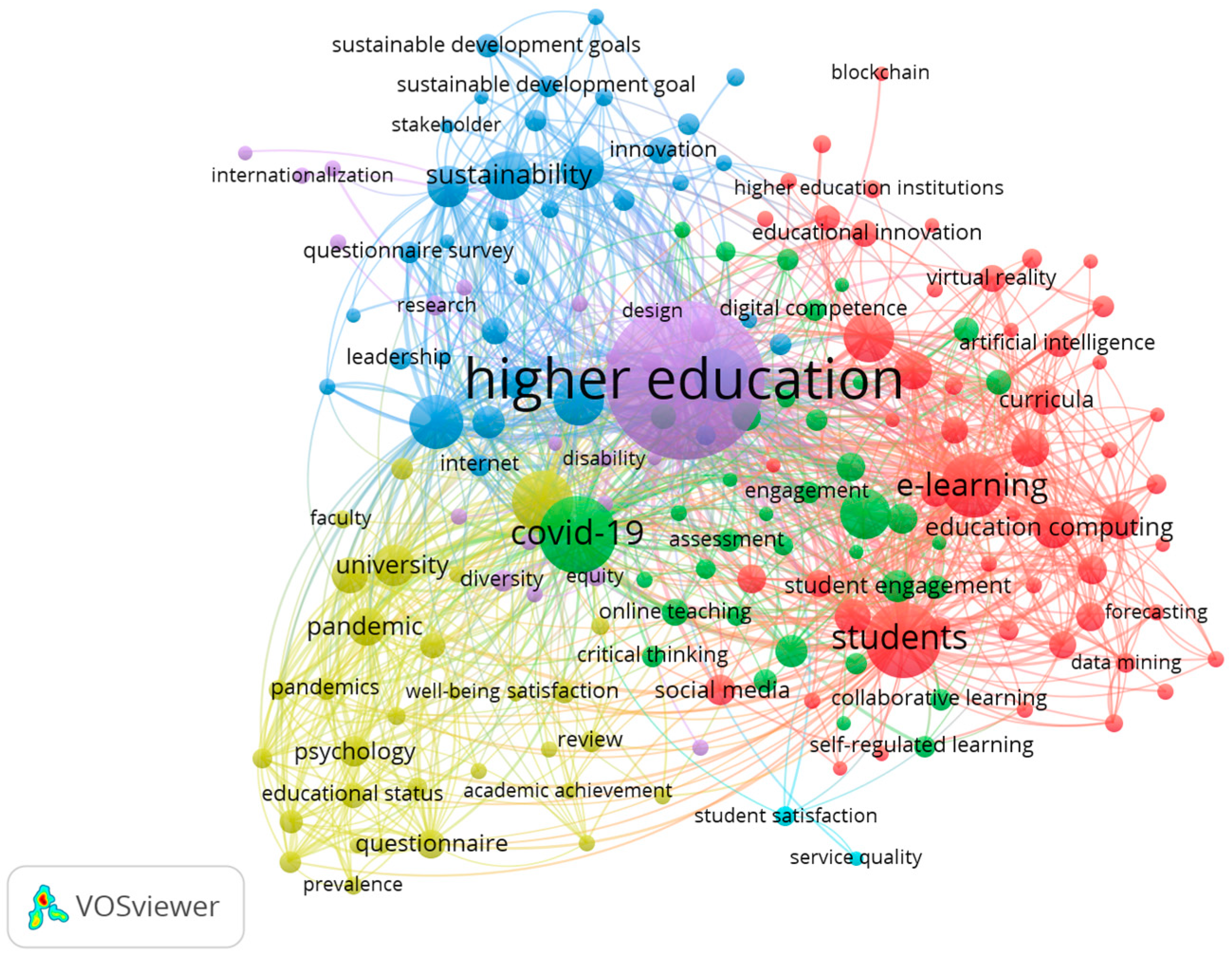

Bibliometric analysis (

Figure 1) is crucial for understanding the evolving relationship between AI and higher education across different periods. It provides a systematic and quantitative approach to analyzing the vast and growing core of literature on this topic. Bibliometric studies can reveal how research focus has shifted over time, identifying key milestones, emerging themes, and influential works by examining publication trends, citations, and keyword usage. It helps researchers and educators track the development of AI applications in higher education, from early explorations of AI as a tool for specific tasks to its current role in transforming learning environments, institutional management, and educational policy.

Furthermore, bibliometric analysis can highlight the impact of specific AI technologies and their changing roles within higher education. For example, it can trace the evolution of AI from its initial use in intelligent tutoring systems to its current applications in areas such as personalized learning, student support, assessment, and institutional analytics. By mapping the intellectual structure of the field, bibliometric studies can identify the most active research areas, the leading scholars and institutions, and the connections between different sub-fields. This information is essential for understanding the current state of research and identifying promising directions for future investigation.

Finally, bibliometric analysis offers valuable insights into AI’s broader societal and educational implications in higher education. It can reveal how concerns and opportunities related to AI in education have evolved, reflecting changes in technology, pedagogy, and societal values. By analyzing the discourse surrounding AI in higher education, bibliometric studies can help to identify ethical considerations, policy challenges, and potential benefits. This comprehensive understanding is crucial for guiding the responsible and effective integration of AI into higher education systems, ensuring that it enhances learning, promotes equity, and supports the overall mission of higher education institutions.

3.3. Description of the Survey

The countries for the survey were selected to ensure maximum social, cultural and economic diversity [

73]. Students from four Eastern European countries (Bulgaria, Poland, Slovakia and Ukraine) and one partially Eastern European country (Kazakhstan) participated in the survey. Both state and non-state universities are participating.

Internal validity was ensured through pilot testing of the questionnaire and expert verification of the wording. Reliability was measured using standard statistical procedures. The instrument was tested in a previous study [

16]. The survey was based on self-assessment. Self-assessment allows us to consider students’ subjective perceptions regarding using AI in the educational process. The questionnaire includes three parts: (a) an appeal to respondents, (b) metric questions and (c) the main part. The full text of the questionnaire is included in

Appendix A.

Part (a) informs respondents about voluntary and anonymous participation [

16]. Students who did not want to answer the questions in the questionnaire refused to participate. The principle of voluntary and anonymous involvement ensured the minimization of unreliable questionnaires.

Part (b) includes four standard questions about the country of residence and demographic characteristics [

16].

Part (c) is the central part of the electronic questionnaire [

16,

73]. The main research questions are directly related to the main aim of the work: How often do you use AI in your learning process?

Research hypothesis 2 relates to the first question.

Research hypothesis 3 relates to the second question.

Research hypothesis 4 compares the answers relating to the first and second questions.

There were five answer options:

Every day;

3–4 times per week;

1–2 times per week;

1–2 times per month;

Never.

Instead of a Likert scale, a frequency scale was used (daily, 3–4 times a week, 1–2 times a week, 1–2 times a month, never), since the study aimed to record the regularity of AI use rather than to measure attitude/intensity. The study required binarization of the data (daily = 1, non-daily = 0) to test hypotheses through

t- and

z-tests. The classic Likert scale does not reflect the regularity of behavior (daily vs. non-daily). This approach is used in several studies of digital practices [

16,

73]. The chosen time intervals are based on the tradition of surveys on the frequency of actions in the educational environment [

16,

73] and allow the results to be compared with previously published works.

This scale is not linear, as we have only two options for further analysis. We decided to combine the answers into two groups:

Students regularly use AI in the educational process. Answers: every day.

Students do not regularly use AI in the educational process. The answers are 3–4 times per week, 1–2 times per week, 1–2 times monthly, and never.

We assumed that the regular use of AI in the learning process corresponds to the daily use of AI in the learning process. Therefore, we were interested in only two groups of answers: “daily” and “not daily.” The second group includes all other answer options. These answers range from “never” to several times a week. For ease of decision-making when answering, we prepared a five-step scale.

The questionnaires were hosted in the cloud service of the National Louis University. This measure allowed for the creation of separate questionnaires for each group of respondents. In addition, it helped to eliminate errors in collecting and processing the respondents’ answers.

3.4. Respondent Groups

Sequential (nested) sampling was used in the study [

16,

73]. While selecting the groups of respondents, we also sought to achieve diversity. All respondents were undergraduate students (

Table 1). They were studying sciences not related to IT or computers. The students could not study AI technologies as professionals [

16]. The respondents were not students studying AI as a tool for solving pedagogical problems. Most likely, the respondents had different personal experiences of using AI for personal, professional, and everyday purposes. This approach also helps to achieve diversity in the survey.

Thus, the empirical part covered 1197 respondents (

Table 1). Eight groups of students from five Eastern European countries took part in the survey. Of these, 321 were men and 869 were women. Only seven respondents indicated “other” gender. The number of groups varied from 49 to 364 participants. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 64 years. Thus, social and cultural diversity was achieved. The student survey led to new empirical findings regarding the sustainability of higher education, intellectual education and AI tools. We received a general picture that allows them to explore the hypothesis of a new 3D model of the higher education services market.

To calculate a representative sample, we use Cochran’s formula:

where

n0—initial sample size for large populations (before any adjustments for finite populations);

Z—

z-value (e.g., 1.96 for 95% confidence);

p—estimated population proportion (use 0.5 if unknown);

E—margin of error (

E = 0.03).

Table 1 shows that the number of respondents exceeds the set value according to Formula (1). For local samples (university), the conditions of the minimum required proportion of respondents (20% of the total number of the category) are met.

3.5. Verification of Statistical Hypotheses

We verified statistical Hypotheses 1 and 3 using a standard procedure (

t-statistics [

73,

74]). We verified statistical Hypothesis 4 using a standard procedure (

z-statistics). A special prompt for ChatGPT 3.5 was used to calculate statistical indicators.

The essence of the statistics was to check whether the number of students who regularly use AI in the pedagogical process is zero. Given the importance of the two groups of answers, the answers “every day” were assigned a value of 100.00. All other answers were assigned a value of 0.00. Thus, the respondents’ answers were processed on a dichotomous scale: 0.00 and 100.00.

Testing hypotheses involves comparing the sample mean, M(x), with a given number μ0. One-way testing was chosen because the response rate of respondents could not be less than 0.00%.

We used a standard verification level of 0.05 (α = 0.05). The sampling error was 3.00%. We didn’t take random deviations into account.

After completing the discussion, we wrote conclusions.

5. Discussion

The study’s results confirm the theoretical significance of the conceptual hypothesis about the emergence of a third player (artificial intelligence) in the higher education system and its practical implications. In the previous sections, we focused on bibliometric analysis, statistical hypothesis testing, and the substantiation of a new 3D model. At this stage, the discussion bridges the gap between theoretical understanding and the level of specific managerial and pedagogical decisions, demonstrating that the proposed model can potentially transform educational processes in the real academic community.

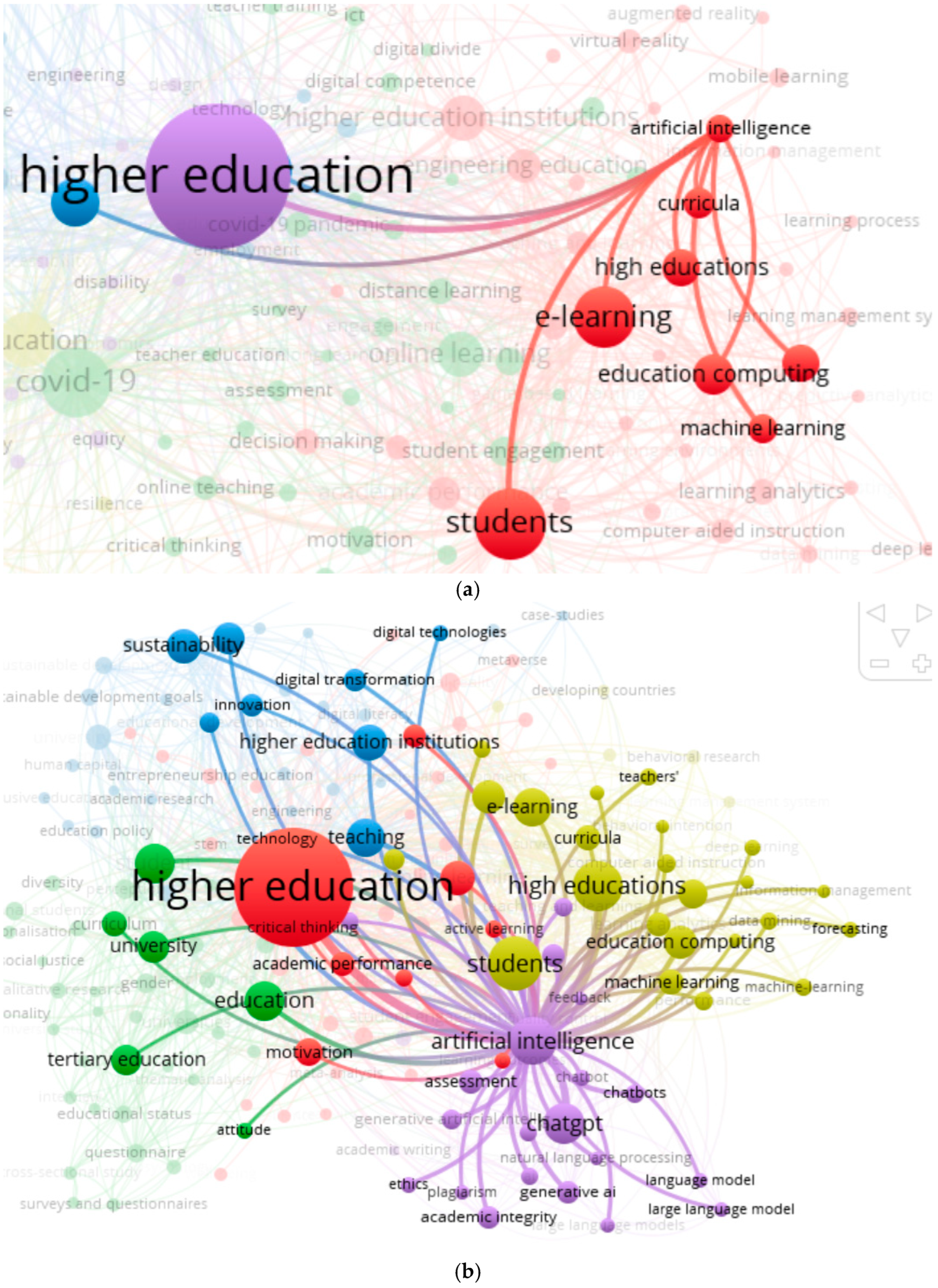

After studying the results of theoretical research and the practical experience of other authors, this work hypothesized that the third active player (AI) appeared in higher education services. This third player (uninvited assistant) could become a full-fledged player in the higher education services if at least one of the traditional market players regularly uses AI in the pedagogical process. After conducting the bibliometric analysis, hypothesis 1 was accepted. The alternative hypotheses were accepted for hypotheses 2, 3, and 4 after the local empirical study and verification of hypotheses. Thus, we adopted the conceptual hypothesis.

It should be emphasized that using two methods: bibliometric analysis and empirical survey, is not a simple “mix of methods”. This dual design allows for testing hypotheses at different levels: bibliometric analysis record changes in academic discourse. At the same time, the empirical survey of students reflects practices and perceptions in the educational environment. The combination of these levels enhances the reliability of the findings.

The use of AI in the pedagogical process was tested by students (X-axis). The verification of statistical hypotheses proved that the number of students who regularly use artificial intelligence in the pedagogical process is greater than zero. The null hypotheses 2, 3, and 4 were tested and rejected on a sample of 1197 respondents from 5 Eastern European countries. From the point of view of statistical theory [

73], rejection of the null hypothesis and acceptance of the alternative hypothesis is robust evidence. The standard testing level is 0.05, and the standard sampling error is 3.00%.

Accepting the conceptual assumption complicates the didactics of higher education. Therefore, these factors are very important and are studied in the world scientific literature [

10,

12,

23,

34,

38,

44,

50,

51]. Acceptance of the hypotheses means that the model of the higher education services market has changed from flat (2D), described by two axes X and Y (

Figure 5), to three-dimensional (3D), defined by three axes X, Y, and Z (

Figure 7). The presented 3D model reflects a broader process of social transformation: changes in subject roles, norms of interaction, and expectations from the educational process under the influence of digital technologies.

This model takes another step forward compared to the concept of three-subject relations [

9] in didactics. Textbook [

9] proposed to accept the “Information and Educational Environment” as the third player in the pedagogical process. However, at that time, they could not imagine the “Information and Educational Environment” as a subject of didactic relations [

9]. Subject–subject relations in didactics assume that the student and the university teacher are considered subjects of the pedagogical process (

Table 7). In such relations, each participant in the educational process is perceived as a unique individual with their interests, life goals, and system of value orientations. AI is characterized by a high degree of individuality, autonomy, and uniqueness in the pedagogical process. In the three-subject didactic relations, we of the work [

9] considered the “Information and educational environment” as a special environment for organizing the mental activity of the subjects of the educational process. At the same time, we declared the emergence of three-subject didactics as one of the areas of pedagogical science [

9]. From a theoretical point of view, introducing AI in higher education contributes to personalized learning and increased technological competence of students [

22]. Thus, the new 3D model (

Figure 8) is the next step in developing the didactic theory of subject–subject relations.

The quality management of higher education services and the management of higher education services have also become more complicated. Since relations with AI have some ethical and legal difficulties (

Table 7), the emergence of the third player (AI) complicates the quality management of higher education services. Source [

16] shows that the number of students who think AI threatens higher education can range from 10.17% to 35.42%, directly affecting the quality of higher education management. The new 3D model (

Figure 8) clearly defines three players, including quantitatively on the part of consumers of educational services (

Table 5). The bibliometric analysis confirms the importance and correctness of representing the higher education services as a 3D model. The size of the purple circle in the period 2023–2025 (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4b) is significantly larger than that of the red circle in the period 2020–2022 (

Figure 2 and

Figure 4a). The red (

Figure 4a) and purple (

Figure 4b) circles correspond to the number of mentions of the keyword “artificial intelligence” in the scientific discourse in the field of higher education.

Figure 4a,b helped us to travel back in time and compare the activity of students’ interaction with AI in two periods.

Figure 4a,b clearly reflect the connection of AI with students. The size of the circles corresponding to students is more significant than that of AI (

Figure 4a,b). This fact means that the relevance of studying the role of student interaction with AI has increased. This result is consistent with the data in

Table 3. The circles symbolizing the mention of academic staff are absent in both Figures (

Figure 4a,b). Our study showed that from 1.67% to 21.76% of students regularly use AI in the educational process (

Table 3). Thus, the new 3D model is the next step in improving the management of higher education services. Examples of using AI as assistants to academic staff and, sometimes, instead of teachers are available in many scientific publications. For instance, papers [

12,

20] focused on teaching and assessment in higher education in the context of AI chatbots such as ChatGPT. Paper [

19] shows that approximately 20% of Spanish institutions use AI chatbots instead of university staff to serve applicants. The paper [

78] shows that some professors have used virtual teaching assistants for several years. AI tools can measure how much a student has acquired a skill and personalize educational content accordingly [

79]. We refer to the paper [

80], which explains the prospects for implementing AI technology to promote surgical education. In the paper [

16], the lower limit is shifted by 8.50%, and the upper limit is shifted by 13.66% compared to the data in

Table 3. That is, the decision on the danger of AI for higher education is made by students who do not regularly use AI in the educational process (8.50–13.66%). This is an additional result of the current study: the number of students who regularly use AI in the educational process should be increased by 8.00–14.00%. Then, people who are more familiar with AI will decide on the possible dangers of AI. The obtained result in the new 3D model corresponds to the content of the sixth technological paradigm since it includes information technology [

5,

81,

82]. Paper [

5] showed that the top 10 most cited papers in pedagogical research for 2023 are devoted to AI use.

These results are essential for the field of educational services. Even though global interest in this topic has decreased, scientists continue to study this area (

Table 7).

This new three-dimensional configuration of educational relationships has theoretical significance and practical value for various educational service providers.

First, for academic staff, the results offer the prospect of adapting traditional teaching methods to the constant presence of AI tools within the university community. A practical consequence could be the introduction of “AI literacy” modules into academic staff professional development programs. “AI literacy” modules will help academic staff develop skills in pedagogical design using generative systems. In particular, they can use AI to analyze written assignments, create differentiated assignments, and obtain prompt student feedback. We see such an example at National Louis University (wsb-nlu.edu.pl, accessed on 5 September 2025).

Second, the regular use of AI becomes a factor in developing new academic competencies for students. This fact promotes the development of skills for critically evaluating large volumes of information, managing cognitive load, and individualizing educational trajectories. Moreover, the identified gap between the need and actual use of AI reflects the need to develop students’ skills in the ethical and informed use of AI tools. A practical step in this direction could include courses focused on academic integrity in curricula.

Thirdly, for university administrations, the 3D model of higher education sets new benchmarks for quality management, including through digital didactics. In particular, the use of AI-based learning analytics systems for the early detection of academic failure, the risk of expulsion, and the monitoring of students’ careers and educational trajectories in their senior years could be of practical significance. These systems allow for more precise adjustment of the internal quality assurance system for educational services and reduced expulsion rates.

Finally, for governments, the practical basis of the study is the need to develop a regulatory and ethical framework for the use of AI in educational services. With the growing number of students using AI daily, creating uniform rules of academic conduct, including acceptable and prohibited practices, is becoming an essential requirement. Thus, a discussion of the empirical results in the context of the proposed conceptual model demonstrates that the transition from a 2D to a 3D model of educational relationships has theoretical and practical significance. The findings can serve as a basis for revising university educational strategies, modernizing educational quality policies, and developing students’ and faculty’s competencies for productive interaction with uninvited assistants.

6. Conclusions

The study’s results confirmed the conceptual hypothesis: students’ regular use of AI tools in learning is statistically recorded, creating the basis for describing the higher education system as a three-dimensional model. In this model, the Z axis reflects the degree of AI integration, and students and teachers remain the principal coordinates (participants) of pedagogical interaction. This 3D model is potentially applicable to other areas of social organization, including healthcare, public services, and the labor market, where AI begins to perform the functions of a structural participant.

The scientific novelty of the work lies in the fact that quantitative data (a sample of 1197 students from five Eastern European countries) have been obtained for the first time, allowing us to justify the inclusion of AI as a functional participant in educational services. Thus, the transition from a 2D to a 3D model captures a didactic and social dimension: a new configuration of roles and interactions is being formed in the university environment.

This paper offers the next step forward in the theory of subject–subject relations in didactics. This step is the transfer of AI from the technological environment to an active participant in interaction, possessing the functions of adaptation, initiative, and feedback. This step also opens the way to forming a new pedagogical paradigm of “discrete co-subject didactics”. In the new pedagogical paradigm, AI is not a subject in the traditional philosophical sense. However, AI performs the functions of an active module of influence on both traditional players. The obtained results make it possible to clarify the concepts of subjectivity. For example, for AI, these can be the definitions of “functional subject” or “modulator of the educational process”. Further development of the ethical and methodological basis for interaction with the “uninvited assistant” is also possible.

From a theoretical point of view, the 3D model takes another step in developing the concept of three-subject didactics, which was proposed earlier in works on pedagogy. Unlike previous approaches, where the information and educational environment was considered a passive interaction platform, AI in the proposed model acts as an active subject participating in the educational process and influencing its structure, content, technology, and results. This evolution of didactic theory requires a serious rethinking of the traditional understanding of pedagogical roles. The data obtained can lead to developing new approaches to managing the quality of higher education and pedagogical interaction.

The practical significance of the results is related to the quality management of educational services and the development of digital transformation strategies. Universities and educational authorities can use the presented 3D model to adapt policies, update ethical standards, and improve the readiness of teachers to work in the context of digital transformation. In the theory of educational services, this 3D model can transform higher education services from 2D to 3D (Student–University Teacher–AI). This expansion can be interpreted through the theory of multi-subject service co-creation. AI will be an innovative “technology” and a co-author of value (knowledge) in higher education services. The results obtained make it possible to analyze the process of knowledge creation as a result of interaction between students, academic staff, and AI (value synergy).

Regarding social dynamics, the identified shift reflects a broader process: the introduction of AI changes not only teaching methods, but also the structure of trust, the distribution of responsibility, and the perception of the university’s role in society. These changes affect academic integrity issues, equal access to educational resources, and sustainability strategies.

The presented model thus goes beyond pedagogy and demonstrates how technologies become building blocks of social organization in the digital age. It forms the basis for further research on the impact of AI on social institutions and processes, including in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals. The combination of bibliometric analysis and empirical survey strengthens the reliability of the results. It provides multi-level testing of hypotheses, which is the study’s main contribution to understanding the role of AI in higher education.

The study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the questionnaire did not undergo a full psychometric validation, and the applied scale was used for preliminary purposes without testing for internal consistency. Second, the sample distribution across countries was uneven and determined by technical and organizational conditions rather than planned stratification. Third, the measurement of “regularity” of AI use relied on binarization, representing a simplified assumption at the initial analysis stage. Fourth, the survey was based solely on self-assessment, which captures students’ subjective perceptions of AI use in the learning process; future research will expand by including objective data and more diverse methods to ensure greater comprehensiveness. In the qualitative dimension, the proposed 3D model was constructed based only on students’ experiences and does not yet integrate the perspectives of academic staff. In the quantitative dimension, the 3D model was based on student data from Eastern European countries, limiting the findings’ generalizability. A key methodological limitation of this study lies in using a frequency scale instead of a traditional Likert scale. This decision was deliberate, as the research focused on capturing the regularity of AI use rather than the intensity of attitudes. The chosen approach enabled statistical testing of hypotheses (t- and z-tests) and follows earlier applications of frequency-based measures in digital practice studies.

Future research directions may also be highlighted:

- -

Measuring the role of AI among academic staff and administrators. It is vital to expand the Z-axis of the new 3D model by testing the hypothesis about the symmetry of student and university teacher activity. Such a study will allow us to compare the Z-axis size for students and academic staff. Here, it could be hypothesized that the size of the Z-axis is the same for students and academic staff.

- -

Developing and testing a validated questionnaire on AI practices in teaching. This direction is essential, including for testing the cross-cultural stability of the scales.

- -

Rethinking the 3D model by incorporating theories of the higher education services and digital educational systems.

- -

Qualitative methods for studying the perception of AI as a participant in the educational process, such as in-depth interviews with academic staff/students.

- -

Future studies plan to use multivariate statistical models, such as factor analysis and clustering methods, to more deeply assess the relationships between various variables affecting the use of AI in the educational process. These studies will allow for more complex interactions between factors such as the type of educational content, students’ and academic staff’s experience with AI, and their perceptions of AI effectiveness. Such models will help identify hidden patterns and provide more accurate predictions for integrating AI into higher educational services.