1. Introduction

South Africa has the biggest Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) pandemic in the world [

1]. The prevalence rates are significantly higher in young people aged 15 to 24 years, particularly amongst Adolescent Girls and Young Women (AGYW), where the number of new infections is estimated to be double that of their male counterparts [

1]. Within sub-Saharan Africa, South Africa is the ground zero of the pandemic as it possesses the largest number of HIV cases, with a 13.9% prevalence rate. In 2024, it was estimated that of South Africa’s total population of 60.6 million, about 8.45 million were living with HIV [

2]. HIV incidence and prevalence vary significantly across geographic areas, with most people living with HIV (PLHIV) being concentrated in the Gauteng province [

2].

It is estimated that there were over 240,000 new cases of HIV in 2024 [

1]. It is further asserted that most of the new infections happened among AGYW, with about 2000 AGYW between the ages of 15 to 24 years being infected with HIV in South Africa per week. Poverty, unemployment, economic and social inequalities, and gender disparities increasingly place AGYW from resource-constrained settings at greater exposure to HIV infection through economically driven risky sexual behaviours [

3]. The number of AGYW who have sufficient and correct knowledge about HIV transmission and prevention remains very low, thus partially explaining the rapid spread of HIV in that cohort [

3]. The sex- and age-disaggregated data that have been discussed above highlight the disproportionately elevated vulnerability of AGYW and point to the urgent need to address the socio-economic structural factors that place AGYW at elevated risk of HIV infection.

1.1. Background

Over the years, the Gauteng province has implemented several programmes to mitigate HIV infection among young people. Examples of these programmes include HIV prevention information campaigns; Life Orientation curriculum (taught to learners in schools by the Department of Education); health promotion and Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) education (offered at health facilities and/or through the Department of Health); condom promotion and provision; voluntary male medical circumcision (VMMC); HIV counselling and testing; ART; and some social protection initiatives such as educational subsidies and social grants. The continuously high HIV infection rates among young people and especially AGYW are an indication of the inability of these programmes to provide vulnerable young people with the requisite assets and capabilities to reduce HIV susceptibility. None of the foregoing interventions emerged as a panacea to avert the runaway cases of HIV infections among AGYW because of the complicated constellation of conditions that place them at risk [

4]. Thus, the combination social protection (CSP) was recently introduced in South Africa as a novel strategy that integrates economic strengthening and HIV prevention education. The goal of CSP is to empower AGYW with both economic and social assets to disrupt risks and vulnerabilities to HIV infection.

1.2. HIV Risk Factors Among AGYW in South Africa

Since the first HIV cases were clinically diagnosed in the United States in the early 1980s, the pandemic has wreaked unprecedented havoc in low- and middle-income countries, especially in Africa. The fast spread of HIV infections in sub-Saharan Africa is attributed to numerous drivers. Although researchers concur that the increase in HIV incidence and prevalence is caused by a complex combination of circumstances, there are still disagreements regarding which factors are predominant in spreading the virus [

3,

5]. For example, the rapid pace at which the pandemic is spreading, especially among AGYW, has been attributed to the complicated relationship and interplay among structural determinants [

6]. These structural determinants are defined as a combination of the social, cultural, economic, policy, and societal environments that shape the context in which risk exposure occurs and include poverty, gender imbalances, and unemployment [

6].

1.3. HIV Infection and Gender Disparities Among Young People

Youth is a critical stage when, for many AGYW, vulnerability is consolidated, their rights are irremediably lost, and their health is compromised [

7,

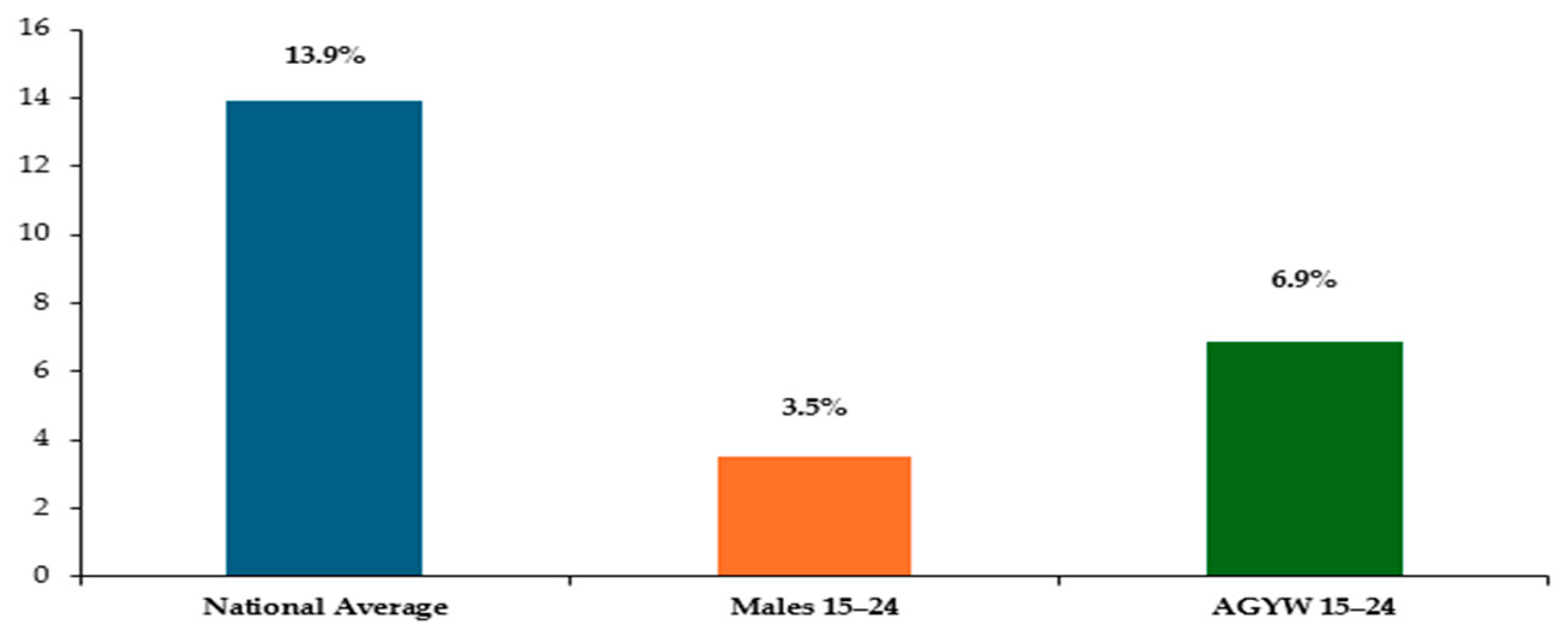

8]. The prevalence of HIV among AGYW (ages 15 to 24) is estimated to be 6.9%, compared to 3.5% among males of the same age [

1].

Figure 1 below illustrates the HIV prevalence disparities among AGYW and males [

1].

Different factors can be attributed to the high occurrence of HIV among AGYW and may vary among sub-regions, countries, and contexts [

5]. Several authors [

5,

8] question the existence of laws and policies that discourage AGYW from accessing healthcare services, especially sexual and reproductive services, without the agreement of parents and guardians in some sub-Saharan countries. The soaring HIV incidence among AGYW has been attributed to societal norms that lead to gender inequalities and unequal power dynamics between males and females, as well as high-risk behaviours by males targeted against their female counterparts [

3,

9,

10]. These behaviours include early sexual debut, transactional sex, numerous concurrent sexual partners, poor and inconsistent condom use, and violence against female sexual partners [

11]. These gender-based disparities and violence, combined with the biological and physiological make-up of women, place AGYW at elevated risk of HIV infection.

1.4. The Poverty and HIV Nexus Among AGYW in South Africa

In countries that are hardest hit by HIV, like South Africa, deprivation and poverty are growing concerns for most households. Empirical evidence has found a positive correlation between the two [

3,

12]. A study conducted in South Africa sought to understand the links between poverty and illness brought about by AIDS; the researchers hypothesised what they termed the “upstream effect of poverty on the likelihood of HIV infection”. They also presented what they called the “downstream effect of AIDS illness on households’ poverty levels” [

13]. The upstream hypothesis explains further impoverishment of disadvantaged people, mainly women, as they are more likely to feel pushed to engage in age-disparity and transactional sexual relationships, thereby exposing themselves to HIV. Limited education and knowledge related to HIV are also seen as enabling factors for infection. In a similar vein, “chronic malnutrition, inadequate sanitation, and limited access to health infrastructure can increase susceptibility to HIV infection among people living in poverty” [

13].

Regarding the “downstream hypothesis”, [

13] argues that AIDS illness can increase the poverty levels in affected families as the economic burden amplifies due to medical, transport and other care expenses. The same authors add that it is also common for households or families with illnesses induced by AIDS to be diverted from productive activities and lose income, especially if the breadwinners are also the carers. Should the carers be children, they will miss many days of schooling, or they might drop out of school completely. Conversely, all these developments may perpetuate the intergenerational transmission of poverty, especially among AGYW.

A longitudinal study in Cape Town found some anecdotal and qualitative evidence that suggested links between poverty and risky sexual behaviour [

14]. They found that AGYW from poorer households were more likely to be sexually active at younger ages compared to their peers from richer households. Further, the young people exhibited very little evidence of utilising condoms, although they were sleeping with multiple partners. Other authors [

15] complement these observations by noting, from their separate studies in other African countries, that the lower the income in the household, the higher the chances that the AGYW in the household did not have accurate information or knowledge on HIV/AIDS. The same authors [

15] further observe that young people, including AGYW from low-income households, did not know where to go or how to access SRH services within their communities.

Resource-limited communities encounter complex and multifaceted challenges that usher in and elevate vulnerability and infection risks for AGYW [

16]. In concurrence, [

3] explains that most AGYW in resource-constrained communities are unemployed, have limited productive assets, are food-insecure and live in circumstances characterised by inequality, poor service delivery, and overcrowding. As these AGYW try to cope with these socio-economic stressors, they end up engaging in risky practices that aggravate their vulnerability to infection by HIV [

3]. Some of the risk practices and behaviours include intergenerational and transactional sex; sex with multiple partners; prostitution; substance misuse; and crime. AGYW from disadvantaged communities also experience limited educational opportunities, which disempowers them and places them at the lowest level of the social, economic, and professional ladders [

15]. The exclusion from educational opportunities often results in marginalisation in mainstream economic activities of AGYW later in their lives.

Anecdotal evidence indicates that the settlements identified as ‘HIV-infection hotspots’, such as Soweto, Alexandra, and Orange Farm in Johannesburg, are poor communities characterised by overcrowding, shack dwellings, high unemployment rates, substance abuse, as well as petty and organised crimes. Consequently, it becomes imperative to explore the experiences of AGYW participating in the group-based HIV prevention programmes (CSPs) in these resource-constrained settings of Gauteng Province. A clear understanding of the combined economic strengthening and HIV prevention interventions among AGYW is paramount to curtailing the spread of HIV among this age and gender cohort. This study sought to achieve the foregoing by answering the research question: In what way(s) has participating in economic strengthening and HIV prevention interventions (the CSP) affected AGYW’s capabilities to address HIV risk factors in their environment?

1.5. Summary of Group-Based CSP Interventions Implemented in Gauteng Province

CSP is a community-based programme carefully tailored to synergistically utilise a collation of behavioural, structural, and evidence-based interventions to address risks and underlying vulnerability in HIV prevention. In this article, CSP means the practice of concurrently combining economic strengthening and HIV prevention modules that are delivered to participants in a group format. Participants in this study attended group sessions and learned the content of the three main modules, viz Financial Capabilities, Entrepreneurship Skills, and Vhutshilo 2. The Financial Capabilities and Entrepreneurship Skills modules anchored the economic strengthening modular pillar, while the HIV prevention content was rooted in the Vhutshilo 2 module.

The economic strengthening component sought to provide socio-economic opportunities to young people to enable them to grow and thrive by becoming economically independent and active citizens living in dignity, thereby lowering the degree of vulnerability that exposes young people to the risks of HIV. Financial Capabilities prioritises financial literacy, building on the understanding that the ability to understand financial concepts and money management (earning, spending, saving, borrowing, and investing) can be translated skilfully into protective behaviours. The Entrepreneurship module has eight one-hour modules and aims to impact young people’s entrepreneurship attitudes and aspirations by training them in the practical business skills needed to understand the development and management of micro business enterprises and co-operatives.

The HIV prevention intervention components, which are delivered concurrently and/or sequentially with economic strengthening, are drawn from the Vhutshilo 2 curriculum. Vhutshilo means “life” in the Venda language. Vhutshilo 2 is a structured HIV prevention and socio-educational curriculum that is delivered to young people using a peer-led model aligned to Comprehensive Sexual Education (CSE) guidelines recommended by UNESCO. Vhutshilo 2 consists of 16 interactive and participatory one-hour sessions, conducted with approximately 15 participants in a group. The curriculum covers topics such as understanding HIV and other STIs; decision-making; gender roles and gender violence; coping without drugs and alcohol; healthy ways to express one’s feelings; understanding and seeking different kinds of support; dealing with loss and grief; healthy relationships; and staying safe in sexual relationships.

1.6. Theoretical Framework

The study utilised the Empowerment Theory [

17] to explore the link between the CSP and the building of the AGYW’s capabilities to address HIV risks and vulnerabilities in resource-constrained settings. The Empowerment Theory was chosen for its congruence with the social work and public health core mandates of preventing, mitigating, and reducing social and public health concerns through people’s empowerment. Zimmerman’s constructs of the Empowerment Theory have been preferred for their coherence, conceptual clarity, client context, and human agency within the social environment. Further, Zimmerman’s Empowerment Theory is regarded as integrative and has received considerable applause over the past decades for transcending intrapersonal, behavioural, economic, political, social, environmental, and interactional components. Zimmerman’s Empowerment Theory has thus been widely utilised as a guide for enhancing individuals’ and groups’ capacities to make choices and then to transform those choices into desirable behavioural outcomes.

The Empowerment Theory, also referred to as an “asset-based approach”, prioritises the building of AGYW’s agency, action, and engagement in change efforts [

18]. The theory focuses on the strengths that AGYW possess and is premised on a central belief that AGYW are champions and experts of their own lives and possess unique perspectives needed for growth [

18]. All these tenets espouse and dovetail well with basic principles of social work and public health practice, such as self-determination, agency, and involvement. This study delineated the context of the AGYW’s HIV vulnerability in resource-constrained settings in South Africa and focused on the extent to which the CSP empowered and benefited the participants to make informed decisions on changing risky behaviour and sexual practices.

1.7. Objective of the Study

While the support of AGYW in the context of HIV has been covered intensively over the years, this study focuses on the impact of a novel intervention (CSP) in South Africa. CSP is a community group-based HIV prevention model that empowers AGYW through social, economic, and gender-responsive approaches. The objective of this study was therefore to explore the benefits of CSP for AGYW in Gauteng in the context of HIV prevention and structural factors.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted from a qualitative paradigm. Non-probability sampling was used to select Gauteng Province as the study setting because the province is the forerunner in implementing the CSP and thus was better positioned to provide crucial information for the study more readily. A typical site-sampling strategy was then applied to select the NGOs in Gauteng that would implement the CSP. Soweto (Region D), Alexandra (Region E) and Orange Farm (Region G) were subsequently selected for this study. These regions have been identified as having the second-largest number of HIV infections and the largest number of AIDS-related deaths [

2]. Typical site sampling was also based on programme maturity, that is, those CBO sites that had implemented quality CSP for long enough periods to be able to produce viable participants for study inclusion.

The population in this study comprised all the AGYW aged 15 to 24 years who participated in the CSP within NGOs in the regions of Soweto, Alexandra and Orange Farm, Gauteng Province, and all the NGOs that were implementing the CSP. A review of CSP attendance registers revealed that 132 AGYW attended group sessions. Since it was not the intention of the qualitative study to collect data from the entire population but rather to describe and understand the experiences of AGYW participating in the CSP, a sample of 18 was selected, from whom the data was collected. Purposive sampling was used to draw samples from AGYW who participated in the study. Purposive or judgmental sampling involves the selection of participants based on the needs of the study and the judgement of the researcher [

19,

20]. Assistance from group facilitators was to provide names of the young people who met the selection criteria below:

They had to be AGYW aged 15 to 24 years.

They had to be participating in the CSP within Soweto, Alexandra, or Orange Farm.

They had to have at least a year’s experience participating in the CSP.

They had to be willing to participate in the study.

They had to be available for the study.

They had to have a basic command of the English language and be willing to do the interviews in English.

In this study, semi-structured interviews were held with AGYW to collect qualitative data, which were analysed and interpreted in terms of specific themes. The study used a semi-structured interview guide that comprised open questions to allow participants to explore and explain issues in depth [

21]. The interview guide was designed in English because the structured CSP curricula are written and facilitated in English. The advantage of the semi-structured interview guides was that they were not restrictive; they allowed participants to respond to questions asked widely. The disadvantage was that the collection of data through semi-structured interviews took a great deal of time, as a lot of data was gathered. Any potentially useful data was recorded thoroughly, accurately, and systematically, using field notes, sketches, and audiotapes. Data collection took place between July and October 2023. The structured interviews were held at venues that guaranteed privacy on dates and times that suited the participants.

In conducting the pilot study, in-depth interviews with four AGYW were undertaken. The aim was to process data collected during the pilot study to refine methodology and data collection instruments by looking at layout, structure, relevance, accuracy, suitability, and appropriateness [

22]. All interview participants who took part in the pilot project were not included in the main study. The research instrument was deemed feasible and appropriate following minor adjustments post the pilot testing.

Creswell and Creswell’s model, known as thematic analysis or data analysis spiral, was chosen for its flexibility, as it does not follow a linear format in analysing and interpreting data [

19]. The thematic analysis allowed the discussion of the common themes from the thick descriptions obtained from the AGYW regarding their experiences in participating in the CSP. The first step that was followed in the sequential thematic analysis process was “organising and preparing the data for analysis” [

19]. This initial step of managing data involved attentively listening to tape-recorded interviews, going through field notes, and transcribing interviews into a Microsoft Word package that was appropriately labelled and stored on a computer. After the organisation and conversion of the data, the second step, “reading and writing memos”, was followed. Transcripts were read in their entirety, and notes were taken on key concepts, leading to the generation of categories and key themes from the participants’ responses. After identifying categories of themes, the third step of “coding” commenced. This step involved writing a word representing a category that identified sub-themes, which were internally consistent but distinct from one another. In the fourth step, the “generation of descriptions and themes”, similar categories and patterns were highlighted to interpret the data accordingly, whilst seeking to provide plausible explanations for the data and linkages among them. The last step, “representing the description and themes”, was conducted by depicting and discussing themes [

19]. This final phase involved the writing of a thematic analysis report. Wherever possible, these themes were substantiated by evidence from participants in the form of verbatim responses.

The goal of abiding by ethical standards is to ensure that researchers realise their imperative of searching for truth and knowledge, morally and humanely [

22]. Ethics clearance for this study was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Fort Hare, South Africa (protocol code: TAN021SZIB01, 11 May 2021). Data were obtained using the principles of voluntary participation and informed consent. For AGYW younger than 18 years, written informed consent was obtained from their parents or legal guardians following a full explanation of the study’s purpose, procedures, and voluntary nature. Thereafter, written assent was obtained from the AGYW participants themselves to affirm their willingness to take part in the study. The information was communicated in clear and age-appropriate language to ensure understanding. Sharing all relevant information with participants helped put them in a position to decide whether to participate or not in the study, thereby eliminating coercion. It was also explained to participants that they could withdraw from the interviews at any time should they feel uncomfortable. Avoidance of deception of participants in this study was achieved by clearly communicating the goal and procedures of the study. There was no misrepresentation of facts, which could have violated the respect of participants. No information was withheld from participants, and participants were informed that they would not receive any payment for participating in the interviews.

Anonymity means that the real names of participants are not used or revealed [

19]. In line with the above-mentioned consideration, no participant information that directly identifies their names or contact numbers was written in the study. Details and information gathered from study participants were treated with secrecy to ensure confidentiality. The interviews were conducted at venues that warranted privacy for the participants. Raw data were also locked in a safe cabinet to ensure that data remained confidential and inaccessible. Lastly, it was also indicated to the participants, through the informed consent letter, that raw data, recorded voice audios, transcriptions and informed consent letters will be securely stored for a minimum of five years, according to the university’s stipulations.

The goal of the study was to explore the experiences of AGYW participating in the CSP. This involved discussing issues around HIV and AIDS, which could have the potential to trigger participants’ suppressed or repressed emotions, specifically those who might have been affected by the HIV pandemic in their lives. Participants were informed about the potential impact of the study and offered the opportunity to withdraw from the study if they wished without any negative consequences. Participants were also given referral information on where they could access the appropriate support, including counselling.

3. Results

Participants narrated their experiences of participating in the group-based interventions at the CBOs. There was unanimity that the AGYW had accrued significant personal growth and acquired social assets. Salient growth areas mentioned include boosts in self-awareness, self-esteem and confidence; determination to become industrious and self-reliant; setting and religiously pursuing life goals; questioning of oppressive gender stereotypes; improved knowledge, confidence and assertiveness around SRH; and appreciation of the positive influence and value of mentorship. AGYW also mentioned how they implemented financial literacy and entrepreneurship skills and started earning their own income. This spawned the confidence and realisation that they could achieve their goals minus the HIV risks associated with transactional sex.

Table 1 below presents the socio-demographic characteristics of study participants.

3.1. Boosts in Self-Awareness and Confidence

Several girls who participated in the group sessions appreciated that they had opportunities to introspect and reflect, which allowed them to know and appreciate themselves better. Most participants felt that the groups provided safe and non-judgmental spaces conducive to boosting self-esteem and personal growth. This self-knowledge and understanding spawned newly found confidence for one of the girls who developed the courage to call out abusive behaviours by her partner:

The best part is that I now know myself better and appreciate the kind of person that I am. I learnt to be more confident about myself. I am now more comfortable talking to my partner about things that I don’t like in a relationship. So, in a situation where there was abuse, I am now able to tell him that I don’t like this and that.

YF3

3.2. Self-Reliance and Independence

Participating in the programmes invoked driven determination to be self-reliant, buttressed by personal resourcefulness and industry. Some of the girls started to take the initiative to cater to their SRH needs with money they had self-earned:

I have been empowered that I have even begun a business of selling sweets in school, so I can make money for myself, and with that money, I can buy myself sanitary pads instead of asking in the house, yeah. Everything that I gained, I worked for it and did not depend on someone else, or to always complain that we are struggling in this community.

YF4

3.3. Setting and Focusing on Life Goals

By participating in the programmes, some AGYW developed long-term perspectives focused on setting and achieving life goals. This came with the realisation that unsafe sexual practices and unplanned pregnancies could scupper valuable lifetime gains. As a result, there was a marked resolve by the participants to eschew immediate pleasures for desirable prospects:

I am aware that if I get pregnant, then I’m adding to the statistics of teenage pregnancies. So, that knowledge keeps me focused on my goals that I have because I am aware of my goals, and I must take the knowledge and put it into practice so that I can fulfil those goals that I have set for myself.

YF3

3.4. Challenging Gender Stereotypes

Gender norms and attitudes were explored in one of the HIV prevention sessions. This led some of the participants to challenge the patriarchal dominance of men in their families and society. The participants developed an awareness that girls and women could step out of men’s shadows and make significant career achievements beyond the kitchen. A lot of the girls also perceived themselves as equal to their male siblings, thereby changing family dynamics around chores:

Yeah, it has broadened my view that I am equal, even with my brother, because I feel that my mother sometimes does not allow me to do certain things because I am a girl. So, with this programme, it has taught me that even in a relationship, I cannot allow the man to take all the decisions for me, but we must do together because we are in a relationship.

YF17

However, there was a perception shared by some of the girls that some families and communities remained entrenched in traditional beliefs that idolised male achievement and dominance while suppressing female empowerment. This seemed to frustrate one of the participants whose mother had participated in the Let’s Talk programme, where gender roles and women’s empowerment were explored:

Factors that have contributed to me not achieving, I think support from parents. As much as my mother did Let’s Talk, but she also still has that stereotype that girls belong in the house, they need to be wives and have children. So, when we talk about careers, she goes back and says you will marry a rich man and have children and a good life. She doesn’t talk about me being a rich woman and having a husband and children.

YF5

3.5. Improved Knowledge, Confidence and Assertiveness Around SRH

Many participants shared that they acquired important SRH knowledge, which in turn galvanised their resolve to demand and insist on safe sex practices with their partners. Safeguarding health assumed paramount importance for most participants, whereby regular testing for HIV became an expected norm. Some participants delighted in the variety of protective SRH options at their disposal, which gave them freedom and a sense of security to explore their sexuality. Yet, some of the girls who opted for using PrEP were wary of telling their partners for fear that the male partners would then object to using condoms:

Now I can stand my ground as a lady. I can say we cannot engage in sexual intercourse without using protection, that’s one thing. Then secondly, we also need to get tested before having sex. I need to know your status and you need to know mine so that we need to know all the precautions that we need to take in our relationship without endangering anyone’s health.

YF9

I am happy that I now have the freedom to be involved in sexual activities the way I want. For example, I can use dual or triple protection at the same time, which is a condom, contraceptives, and PREP.

YF10

I am one of the girls who went for PrEP. So, I take the treatment every day that I was given at the clinic. But I don’t tell my boyfriend that I am on PrEP so that we can continue using a condom so that I won’t fall pregnant.

YF5

We are no longer afraid of doing HIV testing. So, when they want us to test, we come in our numbers so that we know our status.

YF16

3.6. Support and Courage to Access Local Health Facilities for Family Planning Contraceptives

Multiple participants described previous fears of approaching local health facilities to access family planning contraceptives. They conveyed that staff at the facilities used to display judgmental attributes and attitudes that petrified the AGYW, resulting in them shunning such facilities, resulting in potentially preventable pregnancies. These participants appreciated the support from their mentors, who sometimes accompanied and advocated for the participants’ rights to free family planning contraceptives. One of the participants shared:

Now we can freely go to the clinic; before, it used to be like a shame that you are going to the clinic for family planning when you are young and still at school, but now, at least through these sessions, our mentors accompany us to the clinic. Nurses at the clinic were not nice at all. The other reason why we get pregnant at an early age is because the nurses wouldn’t allow us to take family planning and so forth, but now we can at least freely go to the clinic and tell them that now I am sexually active and need family planning. I now know my rights.

YF12

3.7. Awareness of Healthy Relationships and Community GBV Services

There was understanding and appreciation of healthy and toxic relationships shared by many participants who also unpacked GBV in its various manifestations, overt and covert. Some participants recounted personal experiences of GBV and abuse and how they had developed the wherewithal to stand up for themselves and share their ordeals with trusted people. Many participants were optimistic about the community GBV services and resources they had recourse to when needed. In some cases, participants told of how they left abusive relationships with the support of their mentors:

And I have also learnt that there are healthy and unhealthy relationships and that if I can come across one, I know where I should go and report if I am being abused and so forth.

YF4

I know where to go when I am experiencing any gender-based violence. Then I know people to report whatever is not sitting well with me.

YF3

Even in my own household, gender-based violence is an issue, and so, with this, it has helped me to open up about the gender norms also. I am also educating my friends who are not part of the sessions, how to speak up and how to identify abuse.

YF8

I got help. They were there to assist and support me, especially on gender-based violence. I can say it changed me because I am no longer in that relationship; I chose to move from that relationship.

YF7

3.8. The Power and Significance of Mentorship

Group sessions were coordinated and run by trained facilitators who doubled as mentors for the participants in their groups. Participants glowingly recounted accounts and episodes that demonstrated the weight and impact of the mentorship they had received. Mentors were praised for driving the participants’ impetus to succeed in life. Mentors were observed to be relatable, and some were seen as sisters and friends in whom the participants could confide and safely obtain accurate information without fear of judgement and recriminations. Equally appreciated was the support in referral to the police, social workers and counselling services. One of the participants authoritatively stated that she probably avoided pregnancy due to the quality of mentorship she received:

I think the mentor played a very important role in my life. I feel like if I didn’t join the programme, I would still be a person who is at risk of so many things, including HIV and pregnancy. Probably, I might have been pregnant by now.

YF8

I can talk to my mentors more than my parents. I don’t have that mother and daughter conversation with my mother. Like it’s easy for me to tell my mentors that my boyfriend did this and this to me, you know.

YF2

The best part is being able to have someone to talk to other than your family members and your friends. Because sometimes we get the wrong information, especially when it comes to our sexual behaviour. I have gained a sister and a friend that I can rely on.

YF5

It has also taught me to teach other girls that they must not fall into the same traps I fell in before I became this person. I now mentor other girls out there.

YF6

3.9. Improvements in Financial Literacy

Improvements in personal and household financial literacy were denoted by shared stories of the participants’ understanding and implementing concepts, including safe income earning, budgeting, savings, bookkeeping, opening bank accounts and shunning transactional sex. With pride, participants narrated how they had evaluated their skill sets and started small subsistence businesses like selling snacks at schools and braiding people’s hair to independently earn an income for personal sustenance. Others talked about the transgenerational transfer of financial knowledge with their parents. In other instances, the participants started earning notable income, which subsequently increased their involvement in important household decisions. The golden thread in the shared narratives tied together the AGYW’s reduced exposure to sexual health risks attendant on relying on older men for financial favours:

Since attending the FC intervention, I have started my own business. I am even selling at school like sweets and simbas. I am even having a book at home where I am doing my bookkeeping, and then I am saving my money. I have opened a bank account.

YF2

What I took from the sessions I can even apply it at home, teach my parents also how to save, you know. Because now, as a family, we sit down like every month to make a budget with the little money we have.

YF2

Now you know that even if the boyfriend doesn’t want to use a condom, you can leave him because you are able to buy your own airtime, or you are able to sustain yourself. Even the blesser, you don’t need to have a blesser if you are empowered to be able to sustain yourself.

YF5

I have my business that I am running. For instance, we are talking about electricity and groceries, then I can cater for that because I also have an income that is coming in. So, I feel like that has also lifted me in some way because now I am involved in decision-making processes of the household and everything.

YF9

3.10. Suggestions to Reach More Girls and Even Boys with the Interventions

Participants were unanimous in their calls and recommendations for more AGYW to benefit from the group interventions. Arguments were raised that current participants had undergone transformative life changes that could only be sustained if the coverage net was extended further in time and wider in geography. A proposal was also made to include more males in the interventions so that heterosexual partners could be on the same wavelength on SRH matters. There was also a sense of unfair gender disparities due to the implicit expectation that AGYW should take the lead in SRH matters while their male counterparts took the backseat:

I think a lot of AGYW need to attend because, with myself and the people we attend with, I think we have changed a lot. And we can talk about things that we have learnt, and we are able to share them with our friends who didn’t attend. So, I believe that if more people can attend, a lot of things can change.

YF18

I feel the programme focuses more on the girls than the boys. Because now I am learning all these things, and now, I must go to my boyfriend and tell him that I have learnt 1, 2, 3. It’s not easy for me to convince my partner. They should also be called for PREP. I cannot be taking PREP alone while the boy is not responsible. I think it should be balanced. When girls are getting pregnant, it’s not only the girl who is affected; we are both affected.

YF15

3.11. Challenges and Limitations Identified by Participants

Participants revealed that, whilst they appreciated the CSP interventions, they encountered some barriers, mixed experiences, and unmet needs that they would recommend being addressed to improve the effectiveness of the interventions. Some AGYW reported that family and community norms remained unchanged despite their personal transformation. Deeply rooted patriarchal beliefs continued to limit the AGYW’s decision-making and empowerment. One AGYW complained that:

My mother still believes that girls belong in the house and should marry rich men.

YF18

Some AGYW hinted at ongoing barriers to accessing SRH services at clinics. They cited nurses’ attitudes, stigma, and transport issues as structural obstacles. One participant stated the following:

Some girls still get pregnant, although they now know their rights. Some cannot afford to pay for transport fares, and in some clinics, some nurses show us an attitude and do not allow us to take family planning.

YF12

Economic and sustainability limitations were also cited as empowerment barriers by some AGYW. Although several participants started small businesses, some AGYW reported that sustaining these ventures was difficult due to limited financial capital and access to formal markets:

What I took from the session is difficult to apply at home as we are not given financial resources to support our small business ventures.

YF2

4. Discussion

This study explored the perspectives and lived experiences of AGYW who participated in a group-based HIV prevention intervention in Gauteng, South Africa. The primary aim was to understand how the intervention influenced their lives and addressed the structural and behavioural factors that heighten their vulnerability to HIV infection. The findings reveal that the intervention had an empowering impact across several domains. It significantly enhanced AGYW’s self-awareness, self-confidence, and sense of independence; agency; encouraged goal setting and long-term planning; fostered financial literacy and entrepreneurial thinking; and empowered participants to challenge harmful gender norms. The programme also improved knowledge and assertiveness around SRH, increased access to health services, raised awareness of GBV and available support structures, and underscored the vital role of mentorship. Participants further advocated for broader programme reach and the inclusion of boys to foster shared responsibility in SRH. The discussion that follows critically examines each of these themes and considers implications for strengthening such interventions.

The findings of the study reveal that participating in the group-based intervention helped the AGYW to develop self-awareness and confidence to negotiate relationship dynamics and challenge abuse. Arguably, the AGYW acquired abilities to critically reflect, build identity, and strengthen personal agency, which laid the foundation for positive disruption of gendered vulnerability to HIV. The findings of the study echoed those which established HIV Peer Education programmes were a successful modality for AGYW to engage with peers in supportive group settings, and that this facilitated personal development, specifically their self-confidence and self-esteem [

15]. Our findings also show that the intervention helped increase the AGYW’s SRH knowledge, which improved their sexual self-efficacy while also encouraging positive behavioural choices such as contraceptive uptake. AGYW benefit immensely from group-based interventions as they offer safe spaces that foster discussion, emotional expression, and knowledge-sharing, which in turn build resilience and empowerment. We encourage all HIV prevention programmes to consider integrating structured group-based intervention in their efforts to address the substantial cases of HIV among AGYW.

In this study, one notable finding was that financial literacy not only fostered immediate protective behaviours but was also key to activating financial agency for AGYW. Economic empowerment through financial capability and enterprise education significantly contributed to the AGYW’s independence, allowing them to meet their basic needs without resorting to transactional sex. The shift from dependency on older men to self-generated income illustrates a powerful HIV prevention pathway. Financial literacy spurred intergenerational learning, as AGYW shared budgeting skills with parents. These findings align with existing literature that links financial literacy to poverty reduction and lower HIV risk among AGYW [

13]. Financial independence shifts AGYW’s reliance from risky partnerships to sustainable, self-managed livelihoods, thus lowering exposure to HIV. Thus, financial agency is key to AGYW empowerment in poor settings. To improve the impact of financial literacy activities for AGYW in poor settings, the researchers recommend the provision of seed grants and linkages to savings groups and youth cooperatives. This will allow the AGYW to turn acquired financial knowledge into sustained entrepreneurial action.

The study also found that participating in group-based HIV prevention interventions equipped AGYW with knowledge of SRH and long-term planning. It could be argued that this helped to cultivate a future-oriented mindset among AGYW, reinforcing the delay of risky sexual behaviour. The internalisation of personal goals among AGYW reflects the programme’s success in shifting immediate gratification mindsets to future-focused thinking. Mirroring the findings of other studies in South Africa, our findings show that when AGYW perceive education and career aspirations as achievable, their likelihood of engaging in risky behaviours diminishes [

10,

23]. Our findings must be further understood within the broader socio-economic context, where poverty and limited opportunities diminish the hope and aspirations of AGYW, often pushing them toward risky behaviours.

Our findings suggest that, through their participation in the group-based intervention, AGYW developed a heightened awareness of how patriarchy and gender stereotypes affect their SRH experiences and overall well-being. Some participants reported gaining the knowledge and confidence to initiate conversations about HIV and SRH with family members, topics that were previously considered taboo. Notably, the findings also indicate that in some cases, there were positive shifts in the restrictive cultural expectations held by parents, who began to accept that AGYW can and should openly engage in discussions about their SRH. Our findings need to be further understood in the context of the larger cultural environment in many African traditional settings, which prohibit sharing and open communication about SRH or personal topics such as romantic relationships between parents and their children.

These findings should be understood within the broader cultural context of many African traditional settings, where open communication about SRH and romantic relationships between parents and children is often discouraged or prohibited. Although parent–AGYW communication holds great potential to address patriarchy and gender stereotypes as well as improve adolescent health outcomes, evidence from studies in sub-Saharan Africa shows that conversations about sex and sexuality are often parent-led, authoritative in tone, indirect, and more focused on warnings and threats than on fostering open, honest, and supportive dialogue. Examples of corroborating studies [

24,

25] show that creating opportunities for open discussions on sexual and reproductive health is an important protective factor for AGYW, leading to improved SRH, including HIV prevention. When parents engage in open discussions about SRH with their AGYW, it can play a critical role in shaping their sexual and gender socialisation. Such communication not only helps prevent early sexual debut, unintended pregnancies, and exposure to sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, but also challenges deeply rooted patriarchal norms and gender stereotypes that often silence AGYW and limit their agency.

One of the most prominent themes that emerged was that participating in the programme developed AGYW’s abilities to adopt safer sex practices, access contraceptives, and confidently negotiate condom use. Participants consistently highlighted that the knowledge they gained through the programme positively influenced their assertiveness in accessing and utilising HIV prevention and SRH services. This finding carries important implications for understanding how equipping AGYW with HIV related knowledge can foster health-seeking behaviour and support informed, positive decision-making. Another important aspect that stood out was the mention that the programme provided an empowering environment where AGYW could redefine their expectations of relationships and gain knowledge about how to access support services for GBV. From a programmatic perspective, this finding suggests that when AGYW learn that they have the right to choose whether to engage in sex, with whom, and when, they become empowered to make independent decisions based on choice and free will. Additionally, with increased awareness of the risks associated with unprotected sex, AGYW are better able to apply the strategies they have learned to prevent unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections, particularly HIV. The integration of the Vhutshilo 2 curriculum was specifically cited as instrumental in strengthening their SRH literacy.

These findings align with other studies [

15,

26] that found group-based and interactive HIV education as effective mechanisms to increase assertiveness of marginalised AGYW to navigate obstacles in accessing SRH interventions. In addition to promoting AGYW’s health knowledge, group-based interventions were noted to create an empowering environment that supported broader well-being through social and peer interactions. These spaces fostered a sense of community, belonging, and connection, while also building AGYW’s assertiveness and confidence to express themselves and make informed decisions. A notable contribution to the findings is that group-based interventions help AGYW overcome communication barriers by allowing them to speak openly about their sexual relationships and family planning choices without fear of being judged, stigmatised, or isolated. It could also be said that group-based interventions not only build social capital but also increase agency among AGYW by fostering critical awareness and empowering them to proactively engage with available health and social support systems.

Our findings show that mentorship was a cornerstone of the intervention, with mentors seen as accessible and non-judgmental allies. The findings also suggest that, when mentors are well trained and supported to effectively engage AGYW, AGYW are more likely to participate and make healthy decisions fully. Mentors were viewed as motivated figures who built trusted relationships with AGYW while delivering evidence-based curricula and facilitating linkages to clinical and community-based health and social services. Capitalising on their experience, the mentors played a critical role in facilitating the growth and development of AGYW by supporting informed decision-making and encouraging positive behaviour change. These findings are consistent with other studies [

27,

28], which emphasise that mentorship is a critical ingredient in the success of community-based youth interventions globally. Mentors help bridge emotional, informational, and logistical gaps in the lives of AGYW, significantly enhancing the overall impact of such programmes [

27,

28]. It is also important to highlight the vital role that mentors play in accompanying AGYW to health facilities. This accompaniment is a key enabler for AGYW to access SRH services [

29]. By accompanying AGYW to clinics, mentors not only help AGYW navigate and overcome systemic barriers, such as stigma and judgmental attitudes, but also serve as crucial advocates and sources of emotional support throughout the process.

Findings show that, in addition to calling for the intervention to reach more AGYW, participants strongly expressed the view that including adolescent boys and young men (ABYM) was essential to maximise the programme’s overall impact [

30,

31]. The inclusion of ABYM was seen as a key mechanism for promoting healthy masculinity and cultivating gender-responsive attitudes among young men, both of which are pivotal in creating a supportive and empathetic socio-emotional environment for AGYW [

32]. The failure to involve ABYM in the intervention was seen as a critical gap that could undermine the programme’s acceptability and effectiveness, given that ABYM often hold greater influence in decision-making around contraceptive use and are frequently implicated in the perpetuation of GBV. Participants’ recommendation to include ABYM in the programme is strategic and aligns with the calls for inclusive, gender-transformative HIV interventions [

12,

33,

34]. Placing the responsibility for SRH solely on AGYW limits the effectiveness of behaviour change efforts, particularly within relationships where mutual responsibility between ABYM and AGYW is critical for sustainable impact.

Some challenges and limitations regarding the CSP were also identified by participants. While most participants shared that they experienced empowerment, personal growth and increased confidence, several challenges were also noted. Some AGYW explained that deep-rooted family and community gender norms still limited their independence and ability to make independent decisions. Others spoke about ongoing barriers in accessing SRH services, including judgmental attitudes from healthcare providers and practical obstacles such as transport costs and long distances to clinics. Some AGYW also mentioned that, although they had learned valuable financial and business skills, it was difficult to keep their small ventures going without start-up capital or external support. These insights suggest that, while group-based interventions are effective in building individual agency and resilience, broader social and structural barriers can make it difficult for AGYW to translate their acquired knowledge and skills into lasting change at the community level.

4.1. Study Limitations

The study was conducted only in one province, namely, Gauteng. As such, the results cannot be generalised to other provinces of South Africa, which are slightly different from Gauteng Province. Moreover, the study only had eighteen AGYW participants. Due to the small sample size, generalisation of study results beyond the sampled area must allow for context. Consideration needs to be given to potential biased responses from the participants due to social desirability. Considering this concept, the AGYW might have given mostly positive feedback to ingratiate themselves with the interviewers. Participants were purposively sampled based on their willingness and readiness to conduct the interviews in English. An argument can therefore be made that only the most confident participants were chosen for the study, leading to biased responses. English language proficiency could be considered a potential confounder in this study. The study also sought the views of AGYW only, hence there was no opportunity to triangulate their narratives against those of their significant others, like friends, partners, teachers or parents.

4.2. Significance of the Study

This study contributes valuable insights into the lived experiences of AGYW participating in group-based HIV prevention interventions in low=socio-economic settings in South Africa. The study highlights how group-based interventions, combining economic strengthening and HIV education, serve as powerful enabling tools for promoting agency, assertiveness, resilience, and informed health-seeking behaviour. In a context where AGYW face intersecting vulnerabilities rooted in poverty, gender inequality, and limited access to SRH services, the findings underscore the potential of structured group-based environments to disrupt risk cycles and empower AGYW to navigate barriers that mitigate access to SRH. The study also advances the evidence base on combination HIV prevention approaches, demonstrating how integrating financial literacy, GBV education, and mentorship can produce psychosocial and behavioural shifts that extend beyond individual participants to influence household and community dynamics. Furthermore, it identifies mentorship and peer connection as critical enablers of programme success. By emphasising the need to strengthen the inclusion of ABYM, the study adds nuance to existing global gender and HIV prevention frameworks and offers actionable direction for designing more inclusive, gender-transformative interventions. Overall, the findings have significant implications for policy, programming, and practice aimed at reducing HIV vulnerability among AGYW and promoting their broader well-being in low-resource contexts.

4.3. Recommendations

The group-based interventions used in this study yielded significant and intended positive outcomes. There is therefore scope to implement the programmes at scale to cover more AGYW and their male counterparts for a wider spread of the interventions’ benefits. Government and other funding and development agencies must therefore commit more resources to the implementation and upscaling of these interventions. Study findings have also shown that despite the noted progress, more still needs to be done to eradicate patriarchal gender attitudes. Parental figures need to be specifically targeted with appropriate interventions in this regard.

Since this study was a qualitative study that was conducted only in Gauteng Province, it is recommended that studies with a similar focus be run nationally to obtain broader views of the experiences of AGYW participating in the CSP and HIV prevention programmes in other resource-constrained settings. Full-factorial Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) will definitively show the impact and efficacy of the group-based interventions considered in this study. Such RCTs should be conducted to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness of the CSP in reducing HIV incidence among AGYW. The current study only focused on exploring the views of AGYW who participated in the interventions. Future studies must triangulate the findings by including other significant people, including parents or guardians.