Outdoor Adventure Builds Resilient Learners for Higher Education: A Quantitative Analysis of the Active Components of Positive Change

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Positive Immersion within OA Experiences

2.2. OA components of Adaptive Change

2.3. Research Purposes

- Establish the immediate changes to inductees’ resilience following a five-day OA residential programme;

- Compare the magnitude and direction of resilience change to similar inductees accessing comparative induction programmes at university;

- Link OA experiences and activities to the most advantageous resilience profiles by equating resilience differences with most powerful OA residential experiences and students’ perceived attributes of resilience.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Design and Measures

3.2.1. Stage 1: Immediate Impact of OA on Inductees’ Resilience

3.2.2. Stage 2: Comparative Analyses of Resilience Change

3.2.3. Stage 3: Powerful Components/Personal Experiences of OA Programming

4. Results

4.1. Stage 1: Changes to CD-RISC Total Resilience (TR) and Subscales

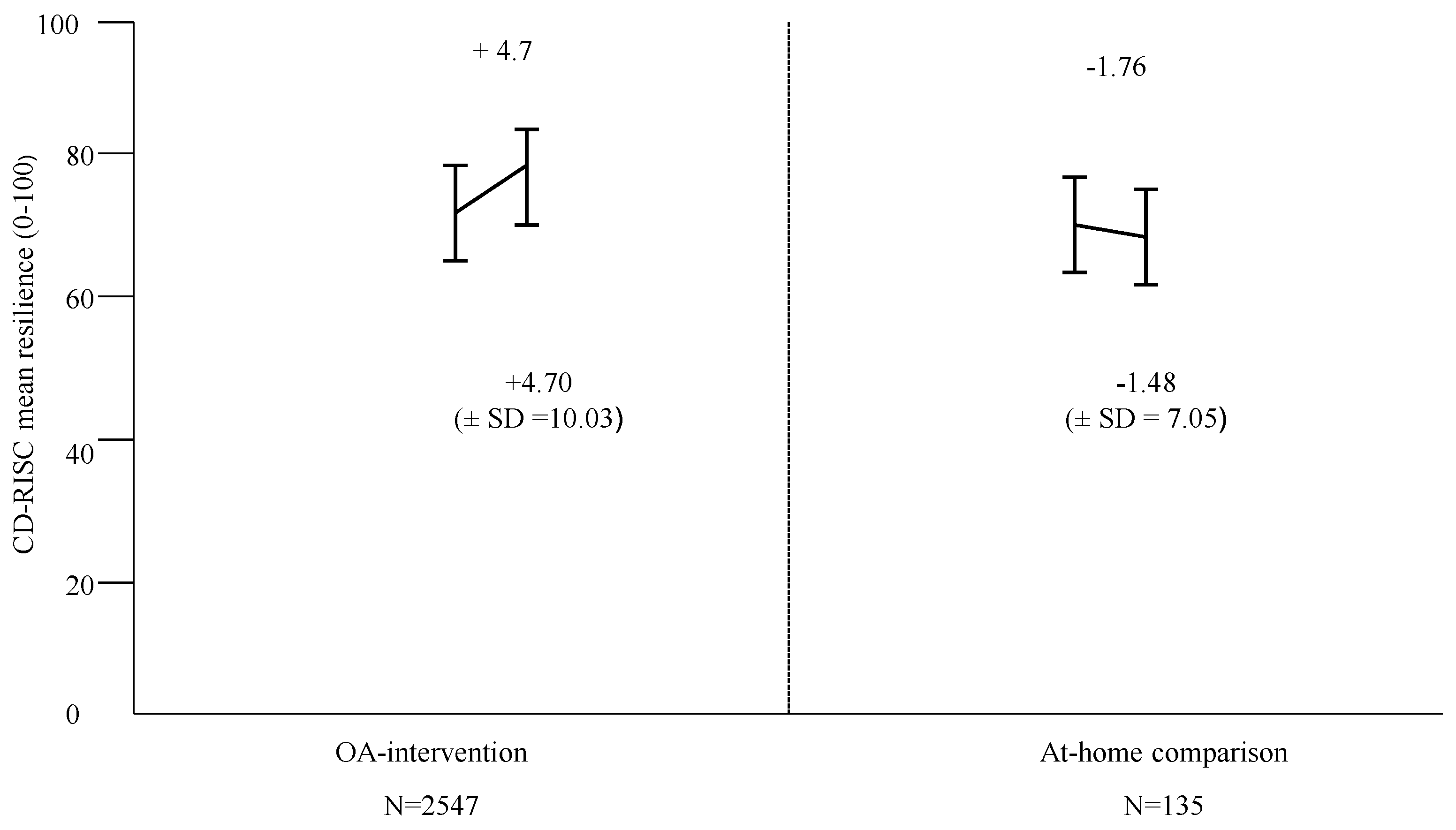

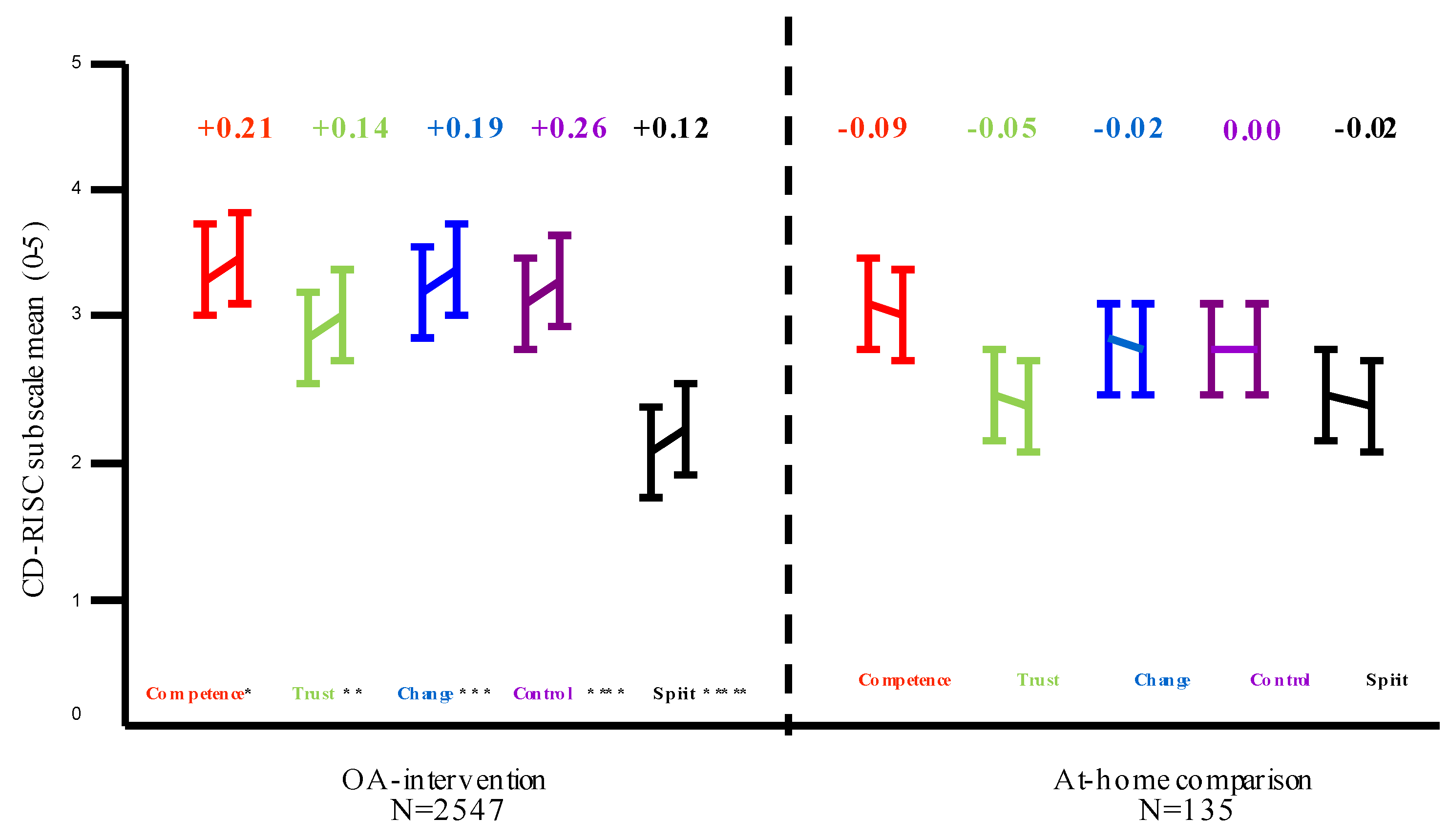

4.2. Stage 2: OA-Intervention Group versus At-Home Comparison Group

4.3. Stage 3: Influential Programme Experiences: Camp Rating Scale (CRS) and Perceived Competencies Scale (PCS)

5. Discussion

5.1. Short-Term Impact of OA on Inductees’ Resilience

5.2. Comparison Group

5.3. Components of OA Residential Programming

5.4. Strengths and Limitations

6. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Doss, B.D.; Rhoades, S.; Stanley, S.M.; Markman, H.J. The Effect of the Transition to Parenthood on Relationship Quality: An Eight-Year Prospective Study. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutts, R.; Gilleard, W.; Baglin, R. Evidence for the impact of assessment on mood and motivation in first year students. Stud. High. Educ. 2011, 36, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radcliffe, C.; Lester, H. Perceived stress during undergraduate medical training: A qualitative study. Med. Educ. 2003, 37, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, C.; Travers, L.; Bryant, F. Promoting Psychosocial Adjustment and Stress Management in First-Year College Students: The Benefits of Engagement in a Psychosocial Wellness Seminar. J. Am. Coll. Health 2013, 61, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhardt, M.A.; Dolbier, C. Evaluation of a resilience intervention to enhance coping strategies and protective factors and decrease symptomatology. J. Am. Coll. Health 2008, 56, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, L.; McKenna, J.; Brunton, J.; Utley, A. Personal development, resilience theory and transition to university for 1st Year students. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Higher Education Advances, Valencia, Spain, 21–23 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aliohani, O. A Review of the Contemporary International Literature on Student Retention in Higher Education. Int. J. Educ. Liter. 2016, 4, 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, M. College Transition Experiences of Students with Mental Illness. Doctoral’s Dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, M. Examining the Relationships Between Resilience, Mental Health, and Academic Persistence in Undergraduate College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2011, 59, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, R.; Guppy, M.; Robertson, S.; Temple, E. Physical and mental health perspectives of first year undergraduate rural university students. Br. Med. Council Public Health 2013, 13, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, K.L.; Armitage, L. Australian Student Engagement, Belonging, Retention and Success: A Synthesis of the Literature; The Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella, L. A Crisis of Resilience at Australian Universities. 2017. Available online: http://news.com.au (accessed on 23 December 2017).

- Marsh, S. Number of University Dropouts Due to Mental Health Problems Trebles. 2017. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com (accessed on 26 May 2017).

- Allan, J.F.; McKenna, J.; Dominey, S. Degrees of resilience; profiling psychological resilience and prospective academic achievement in university inductees. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2014, 42, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, C. The coddling campus. Psychologist 2017, 30, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Shean, M. Current Theories Relating to Resilience and Young People, A Literature Review; Vic Health: Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, M. Resilience, trauma, context, and culture. Trauma Violence Abuse 2013, 14, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Psychological Resilience. Eur. Psychol. 2013, 18, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M. Resilience as a dynamic concept. Dev. Psychopathol. 2012, 24, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Cohen, J.; Turkewitz, R. Resilience and measured gene–environment interactions. Dev. Psychopathol. 2012, 24, 1297–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flouri, E.; Midouhas, E.; Joshi, H.; Tzavidis, N. Emotional and behavioural resilience to multiple risk exposure in early life: The role of parenting. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 24, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVie, S. The Impact of Bullying Perpetration and Victimization on Later Violence and Psychological Distress: A Study of Resilience Among a Scottish Youth Cohort. J. Sch. Violence 2014, 13, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, E.; Shaw, J. Student Resilience, Exploring the Positive Case for Resilience; Unite Students: Bristol, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, H.; Garza, T.; Huerta, M.; Magdaleno, R.; Rojas, E.; Torres-Morón, D. Fostering an environment for resilience among Latino youth: Characteristics of a successful college readiness program. J. Latinos Educ. 2017, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, J.W.; Neill, J.T. Coping Strategies and the Development of Psychological Resilience. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2017, 20, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beightol, J.; Jevertson, J.; Carter, S.; Gray, S.; Gass, M. Adventure Education and Resilience Enhancement. J. Exp. Educ. 2012, 35, 307–325. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, A.; Yoshino, A. The influence of short-term adventure-based experiences on levels of resilience. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2011, 1, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhurst, J.; Hunter, J.; Kafka, S.; Boyes, M. Enhancing resilience in youth through a 10-day developmental voyage. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2013, 15, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, J.T.; Dias, K.L. Adventure Education and Resilience; The double-edged sword. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2001, 1, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarf, D.; Kafka, S.; Hayhurst, J.; Kyungho, J.; Boyes, M.; Thornson, R.; Hunter, J. Satisfying psychological needs on the high seas: Explaining increases self-esteem following an Adventure Education Programme. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2016, 18, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, B.; Gass, M.; Nafziger, C.; Starbuck, J. The State of Knowledge of Outdoor Orientation Programs: Current Practices, Research, and Theory. J. Exp. Educ. 2014, 37, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, B.D.; Kay, G. Perceived impact of an outdoor orientation program for first-year university students. J. Exp. Educ. 2011, 34, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, B.; Chang, H. Outdoor Orientation Programs: A Critical Review of Program Impacts on Retention and Graduation. J. Outdoor Recreat. Educ. Leadersh. 2017, 9, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.; Johann, J.; Kang, H. Cognitive and Physiological Impacts of Adventure Activities: Beyond Self-Report Data. J. Exp. Educ. 2017, 40, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheal, J.; Morris-Duer, V.; Reichert, M.S. Differential Effects of Participation in an Outdoor Orientation Program for Incoming Students. J. Exp. Learn. 2017, 9, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwatrz, F.; Belknap, C.J. Effects of a College Outdoor Orientation Program on Trait Emotional Intelligence. J. Outdoor Recreat. Educ. Leadersh. 2017, 9, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Black, R.; Bricker, K.S. Adventure Programming and Travel for the 21st Century; Venture Publishing: State College, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, M.D. How are adventure education program outcomes achieved? A review of the literature. Aust. J. Outdoor Educ. 2000, 5, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, M.; McAvoy, L.; Klenosky, D. Outcomes from the Components of an Outward Bound Experience. J. Exp. Educ. 2005, 28, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ttiguero-Mas, M.; Donaire-Gonzalez, D.; Seto, E. Natural outdoor environments and mental health: Stress as a possible mechanism. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H.; Stone, J.; Churchill, S.; Wheat, J.; Brymer, E.; Davids, K. Physical, Psychological and Emotional Benefits of Green Physical Activity: An Ecological Dynamics Perspective. Sports Med. 2015, 46, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, D.; Neill, J. A Meta-Analysis of Adventure Therapy Outcomes and Moderators. Open Psychol. J. 2013, 6, 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, E.; Estes, D. The effect of contact with natural environments on positive and negative affect: A meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, E.; Brymer, E.; Clough, P.; Denovan, A. The relationship between the physical activity environment, nature relatedness, anxiety and the psychological wellbeing benefits of regular exercisers. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. Exposure to restorative environments helps restore attentional capacity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumann, K.; Garling, T.; Stormark, K.M. Selective attention and heart rate responses to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobilya, A.; Akey, L.; Mitchell, D., Jr. Outcomes of a spiritually focused wilderness orientation program. J. Exp. Educ. 2010, 33, 301–322. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, J.; Allan, J. Resilience. In Mountaineering, Training and Preparation; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lekies, K.; Yost, G.; Rode, J. Urban youth’s experiences of nature: Implications for outdoor adventure recreation. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2015, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, P.; Houge McKenzie, S.; Mallabon, E.; Brymer, E. Adventurous physical activity environments: A mainstream intervention for mental health. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartling, L. Strengthening Resilience in a risky world, it’s all about relationships. In Women in Therapy; The Howarth Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003; Volume 2, pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J. Outdoor Leadership, Technique, Common Sense and Self-Confidence; The Mountaineers: Seattle, WA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Berman, J.; Berman, D. Risk and anxiety in adventure programming. J. Exp. Educ. 2002, 25, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, D.; Davis-Berman, J. Positive Psychology and Outdoor Education. J. Exp. Educ. 2005, 28, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. Comfort zone: Model or metaphor? Aust. J. Outdoor Educ. 2008, 12, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, K.; Prince, H.; Humbersone, B. Routlege Handbook of Outdoor Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Overholt, J.; Ewert, A. Gender Matters: Exploring the Process of Developing Resilience through Outdoor Adventure. J. Exp. Learn. 2015, 38, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Obradovic, J. Competence and Resilience in Development. N. Y. Ann. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1094, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary Magic; Resilience in Development; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brymer, E.; Davids, K. Experiential learning as a constraints-led process: An ecological dynamics perspective. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2014, 14, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, P.; Moore, K. Adventures in Paradox. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2004, 8, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, B.J. Wilderness Orientation: Exploring the relationship between College pre-orientation programs and social support. J. Exp. Educ. 2006, 29, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, A. A critique of neo-Hahnian outdoor education theory, Part one: Challenges to the concept of ‘character building’. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2003, 3, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Richards, G.E.; Barnes, J. Multidimensional Self-Concepts: A Long-Term Follow-Up of the Effect of Participation in an Outward Bound Program. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1986, 12, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natural England Natural Connections Demonstration Project. 2012–2016: Final Report and Analysis of the Key Evaluation Questions (NECR215); Natural England: Sheffield, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Witman, J.P. Characteristics of Adventure Programs Valued by Adolescents in Treatment. Monograph on Youth in the 1990s. 1995, Volume 4, pp. 127–135. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED384469 (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Higher Education Statistics Agency. Higher Education Statistics for the UK; Higher Education Statistics Agency: Cheltenham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Statistics; IBM SPSS Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016.

- Singh, K.; Yu, X. Psychometric evaluation of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) in a sample of Indian students. J. Psychol. 2010, 1, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobasa, S.C. Stressful Life Events, Personality, and Health: An Inquiry into Hardiness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGahuey, C.A.; Gelenberg, A.J.; Laukes, C.A.; Moreno, F.A.; Delgado, P.L. The Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX): Reliability & Validity. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2000, 26, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Earlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

| Means (±SD) (n) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post | Differences * | Cohen’s d Effect Size (ES) † | % Difference (+) | |||||||||||

| Variable (Range) | Males (1309) | Females (1238) | All (2547) | Males (1309) | Females (1238) | All (2547) | Males | Females | All | Males | Females | All | Males | Females | All |

| CD-RISC (0–100) | 74.64 (12.38) | 74.93 (12.84) | 74.77 (12.59) | 78.98 (11.90) | 79.98 (12.23) | 79.47 (12.07) | t(1308) = 15.22 | t(1237) = 18.27 | t(2546) = 23.55 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 5.81 | 6.74 | 6.29 |

| Competence (0–4) | 3.26 (0.55) | 3.25 (0.55) | 3.26 (0.55) | 3.47 (0.50) | 3.47 (0.51) | 3.47 (0.51) | t(1308) = 15.47 | t(1237) = 16.87 | t(2546) = 22.78 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 6.44 | 6.76 | 6.44 |

| Trust (0–4) | 2.84 (0.55) | 2.83 (0.56) | 2.84 (0.56) | 2.97 (0.58) | 3.00 (0.58) | 2.98 (0.58) | t(1308) = 7.83 | t(1237) = 11.61 | t(2546) = 13.60 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 4.57 | 6.00 | 4.93 |

| Change (0–4) | 3.12 (0.60) | 3.12 (0.63) | 3.12 (0.61) | 3.27 (0.57) | 3.34 (0.56) | 3.31 (0.57) | t(1308) = 9.44 | t(1237) = 13.92 | t(2546) = 16.33 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 4.80 | 7.05 | 6.09 |

| Control (0–4) | 3.00 (0.64) | 3.02 (0.67) | 3.00 (0.66) | 3.27 (0.62) | 3.26 (0.65) | 3.26 (0.64) | t(1308) = 16.07 | t(1237) = 14.08 | t(2546) = 21.34 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 9.00 | 7.95 | 8.66 |

| Spirit (0–4) | 2.00 (0.97) | 2.21 (0.91) | 2.10 (0.94) | 2.11 (1.02) | 2.33 (0.94) | 2.22 (0.99) | t(1308) = 5.27 | t(1237) = 6.60 | t(2546) = 8.34 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 5.50 | 5.43 | 5.71 |

| Categories of Change for Total Resilience | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Negative % | Small Negative to Positive % | Small Positive % | High Positive % | ||||||||||||

| Range Min to Max | M % | F % | All % | Range Min to Max | M % | F % | All % | Range Min to Max | M % | F % | All % | Range Min to Max | M % | F % | All % | |

| CD-RISC | −31 to −2 | 25.8 | 22.4 | 24.1 | −1 to 2 | 22.4 | 22.2 | 22.3 | 3 to 8 | 27.3 | 27.9 | 27.6 | 9 to 47 | 24.6 | 27.5 | 26.0 |

| Competence | −12 to −2 | 16.7 | 13.6 | 15.2 | −1 to 0 | 25.9 | 27.3 | 26.6 | 1 to 3 | 29.2 | 33.1 | 31.1 | 4 to 18 | 28.2 | 26.1 | 27.1 |

| Trust | −15 to −2 | 26.1 | 21.1 | 23.6 | −1 to 0 | 22.7 | 24.0 | 23.4 | 1 to 2 | 21.0 | 21.6 | 21.3 | 3 to 15 | 30.2 | 33.3 | 31.7 |

| Change * | −14 to −2 | 16.8 | 12.4 | 14.7 | −1 to 0 | 35.4 | 33.3 | 34.4 | 1 to 2 | 27.0 | 32.1 | 29.5 | 3 to 14 | 20.7 | 22.2 | 21.5 |

| Control | −5 to −2 | 20.1 | 22.9 | 21.5 | 0 to 1 | 49.9 | 47.6 | 48.9 | 2 to 3 | 23.0 | 22.3 | 22.6 | 4 to 8 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 6.9 |

| Spirituality | −6 to −2 | 10.1 | 8.1 | 9.1 | −1 to 0 | 51.3 | 53.8 | 52.5 | 1 to 2 | 31.5 | 31.5 | 31.5 | 3 to 6 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 6.9 |

| Post Mean Differences (±SD) (n) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA-Intervention Group | At-Home Comparison Group | Differences † | % Difference (+) | Cohen’s d Effect Size (ES) * | |||||||||||

| Variable (Range) | Male (1309) | Female (1238) | All (2547) | Male (61) | Female (74) | All (135) | Males | Females | All | Males | Female | All | Male | Female | All |

| CD-RISC (0–100) | 78.98 (11.90) | 79.98 (12.23) | 79.47 (12.07) | 70.10 (9.46) | 70.56 (10.58) | 70.35 (10.06) | t(1368) = 5.68 | t(1310) = 6.45 | t(2680) = 8.55 | 12.66 | 13.35 | 12.96 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.82 |

| Competence (0–4) | 3.47 (0.50) | 3.47 (0.51) | 3.47 (0.51) | 3.00 (0.53) | 3.04 (0.48) | 3.03 (0.49) | t(1368) = 7.05 | t(1310) = 6.94 | t(2680) = 9.88 | 15.66 | 14.14 | 14.52 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.88 |

| Trust (0–4) | 2.97 (0.58) | 3.00 (0.58) | 2.98 (0.58) | 2.54 (0.43) | 2.60 (0.48) | 2.57 (0.46) | t(1368) = 5.31 | t(1310) = 5.87 | t(2680) = 7.87 | 16.93 | 18.11 | 15.95 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.78 |

| Change (0–4) | 3.27 (0.57) | 3.34 (0.56) | 3.31 (0.57) | 2.94 (0.43) | 2.94 (0.54) | 2.94 (0.49) | t(1368) = 4.47 | t(1310) = 6.12 | t(2680) = 7.45 | 11.22 | 13.60 | 12.58 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.70 |

| Control (0–4) | 3.27 (0.62) | 3.26 (0.65) | 3.26 (0.64) | 2.79 (0.61) | 2.82 (0.58) | 2.81 (0.60) | t(1368) = 5.80 | t(1310) = 5.64 | t(2680) = 8.10 | 17.20 | 15.60 | 16.01 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.73 |

| Spirit (0–4) | 2.11 (1.02) | 2.33 (0.94) | 2.22 (0.99) | 2.36 (1.05) | 2.46 (0.98) | 2.42 (1.01) | NS | NS | t(2680) = 2.25 | −10.59 | −5.28 | −8.26 | −0.24 | −0.13 | −0.20 |

| Variable | Range |

|---|---|

| Never Through Most Days | |

| 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| 1. With people of my own age |  |

| 2. Got on well with people in my group |  |

| 3. Took part in adventure activities |  |

| 4. Able to laugh at myself |  |

| 5. Learned and mastered new skills |  |

| 6. Motivated by the activities I did |  |

| 7. Solved my own problems |  |

| 8. Took responsibility for things |  |

| 9. Took part in formal team-building exercises |  |

| 10. Good connections with residential staff |  |

| 11. Left behind usual unhealthy habits |  |

| 12. Could act in an independent way |  |

| 13. Enjoyed social and academic activities |  |

| 14. Experienced camp leaders |  |

| 15. Free to make my own decisions |  |

| 16. Inspired by the countryside |  |

| 17. Able to choose activities I did |  |

| 18. Cooked for myself and the group |  |

| 19. Felt homesick |  |

| Variable | Range |

|---|---|

| Never Through Most Days | |

| 1 2 3 4 5 | |

| 1. My social relationships now |  |

| 2. My coping with unfamiliar events now |  |

| 3. My personal growth now |  |

| 4. My mental strength now |  |

| 5. My level of optimism now |  |

| 6. My resourcefulness now |  |

| 7. How well I know myself now |  |

| 8. My creativity now |  |

| 9. My ability to predict how others will react |  |

| 10. Forgive others shortcomings now |  |

| 11. My motivation to study now |  |

| 12. My connection to the world now |  |

| 13. Manage life’s ups and downs now |  |

| 14. Forgive own shortcomings now |  |

| 15. My level of hostility now |  |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Allan, J.F.; McKenna, J. Outdoor Adventure Builds Resilient Learners for Higher Education: A Quantitative Analysis of the Active Components of Positive Change. Sports 2019, 7, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7050122

Allan JF, McKenna J. Outdoor Adventure Builds Resilient Learners for Higher Education: A Quantitative Analysis of the Active Components of Positive Change. Sports. 2019; 7(5):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7050122

Chicago/Turabian StyleAllan, John F., and Jim McKenna. 2019. "Outdoor Adventure Builds Resilient Learners for Higher Education: A Quantitative Analysis of the Active Components of Positive Change" Sports 7, no. 5: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7050122

APA StyleAllan, J. F., & McKenna, J. (2019). Outdoor Adventure Builds Resilient Learners for Higher Education: A Quantitative Analysis of the Active Components of Positive Change. Sports, 7(5), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7050122