Advancing Women’s Performance in Fitness and Sports: An Exploratory Field Study on Hormonal Monitoring and Menstrual Cycle-Tailored Training Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Meta-Analysis

2.2. Expert Survey

2.3. Experimental Part (Participants and Procedure)

- Super League team FRANKIVSK-PRYKARPATTIA (Ivano-Frankivsk region): 18 players with a mean age of 21.3 ± 5.3 years.

- Higher League team FRANKIVSK-PNU-DYUSSH-2 (Ivano-Frankivsk): 7 players with a mean age of 21.29 ± 7.8 years.

- Questionnaires: To collect subjective data on athletes’ menstrual cycles and training perceptions.

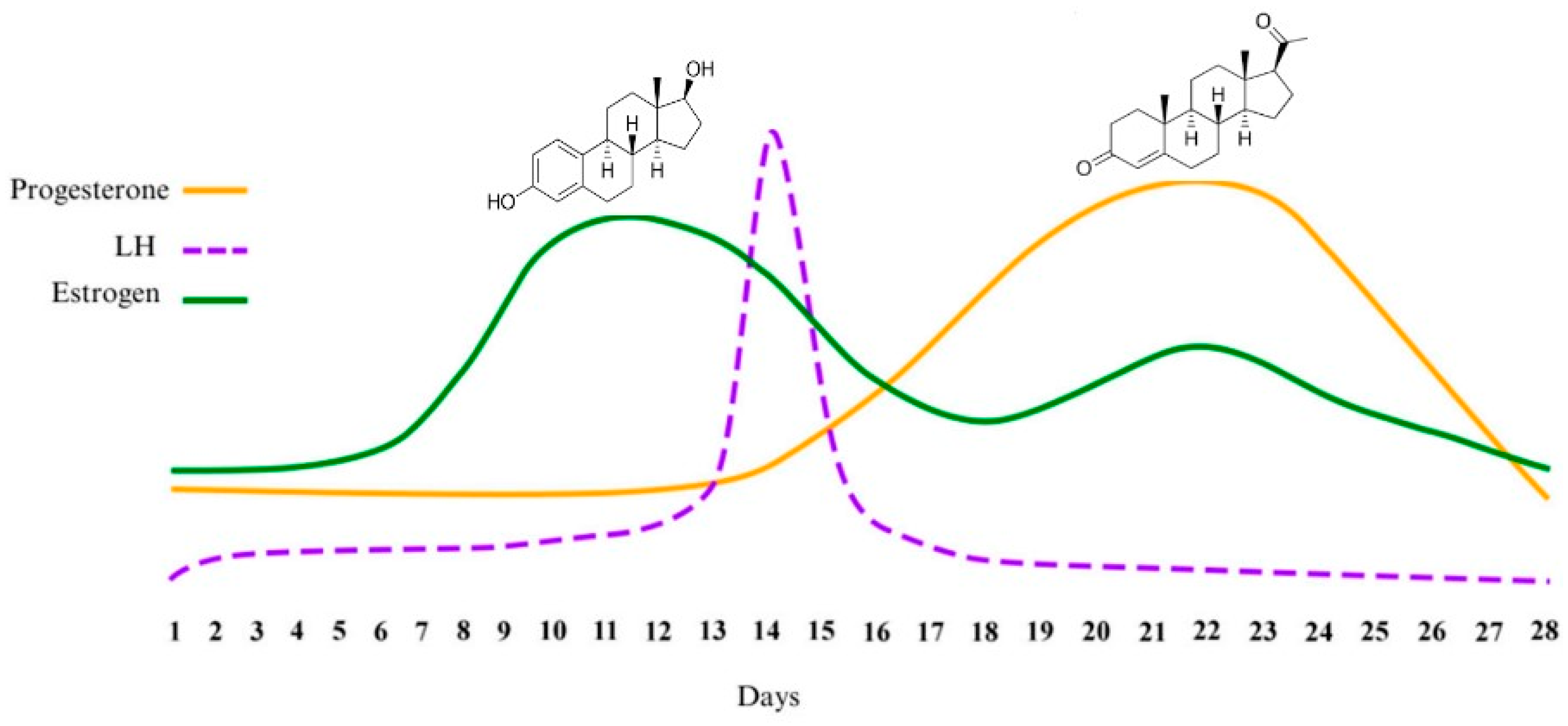

- Estrogen Level Determination: Conducted using the “fern leaf” method to identify cycle phases [36].

- Performance Testing Equipment:

- ○

- Video analysis tools for sprint and movement assessment.

- ○

- Digital timers and stopwatches for precise time measurement.

- ○

- Jump height measurement devices for vertical jump assessments.

- ○

- Weighted medicine balls (2 kg) for strength testing.

- ○

- Court markings and obstacle placements for agility and endurance evaluations.

- Acceleration Test: This measured sprinting efficiency over 20 m from a stationary position, with an intermediate time recorded at the 6 m mark. Video analysis assessed the first-step technique, which involves the biomechanics of the initial sprint step, including foot placement, body lean, and force application, to optimize sprint initiation and efficiency.

- Sprint with Deceleration and Change of Direction: This required athletes to sprint 20 m at ≥95% of maximum speed, execute a controlled braking maneuver, stop, and reverse back to the starting line.

- Standing Vertical Jump with Target Reach: Athletes jumped to touch the highest point on the backboard, with active arm motion and stationary arms.

- Running Vertical Jump with One-Leg Takeoff: Athletes executed an approach jump from the three-second zone with a one-leg takeoff, analyzed via height-to-weight ratio coefficient.

- Jumping Speed Test: Athletes performed consecutive jumps over obstacles in a cross pattern, with jumps counted within a 20 s time frame.

- Speed Dribbling Technique Test: Athletes maneuvered a basketball through a slalom course with three obstacles, finishing with a lay-up shot.

- Medicine Ball Throw for Distance and Accuracy: Athletes threw a 2 kg ball using a single-handed shoulder pass from stationary and running positions within a 2 m wide corridor.

- Defensive Movement Speed and Agility Test: Athletes sprinted from the baseline to five points at the three-point line corners using forward, backward, and lateral movements.

- Specific Endurance Test: Athletes performed a shuttle run across the court (backboard to backboard) with backboard touches, completing three sets of five repetitions with 30 s rest intervals.

- Mid-Range and Long-Range Shooting Consistency Test: Athletes attempted shots from ten locations (five at 4.5 m, five at 6.25 m).

- Free Throw Consistency Test: Athletes attempted 20 free throws, alternating backboards with dribbling sequences.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Meta-Analysis of Methods for Determining the Hormonal Status Level in Women Engaged in Physical Activity

3.2. Experimental Section: Practical Implementation of Hormonal Status Monitoring in Elite Female Athletes

- Acceleration Test (20 m sprint): 3.12 ± 0.15 s (6 m), 3.28 ± 0.20 s (full 20 m).

- Sprint with Deceleration and Change of Direction: 6.74 ± 0.25 s.

- Standing Vertical Jump with Target Reach: 42.5 ± 3.2 cm.

- Running Vertical Jump with One-Leg Takeoff: 58.7 ± 4.1 cm (height-to-weight ratio coefficient).

- Jumping Speed Test: 32.4 ± 2.8 jumps in 20 s.

- Speed Dribbling Technique Test: 7.68 ± 0.35 s.

- Medicine Ball Throw for Distance and Accuracy: 10.8 ± 1.1 m.

- Defensive Movement Speed and Agility Test: 14.92 ± 0.55 s.

- Specific Endurance Test (shuttle run): 41.7 ± 2.4 s (three sets).

- Mid-Range and Long-Range Shooting Consistency: 63.4 ± 7.2%.

- Free Throw Consistency: 81.6 ± 5.4%.

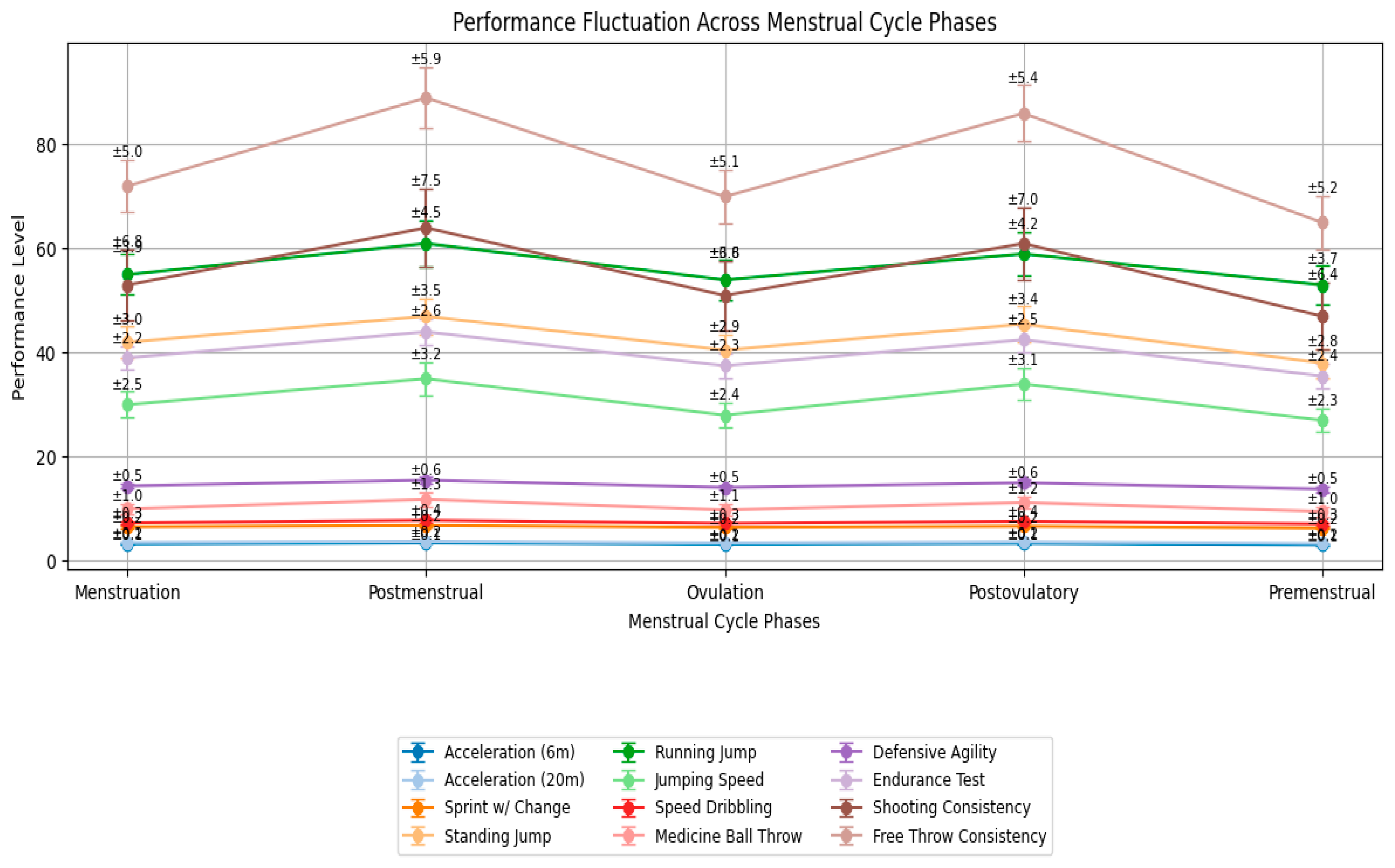

Key Statistical Results

- Acceleration 6 m: F(4,96) = 7.89; p < 0.001; η2p = 0.25. Post Hoc (Bonferroni): Postovulatory vs. Premenstrual: −2.3% (p = 0.012).

- Sprint with Change of Direction: F(4,96) = 14.62; p < 0.001; η2p = 0.38. Post Hoc: Postovulatory vs. Premenstrual: −7.5% (p < 0.001); Postmenstrual vs. Premenstrual: −6.8% (p = 0.002).

- Running Vertical Jump: F(4,96) = 10.34; p < 0.001; η2p = 0.30. Post Hoc: Postovulatory vs. Premenstrual: +5.1% (p = 0.003).

- Speed Dribbling: F(4,96) = 9.11; p < 0.001; η2p = 0.28. Post Hoc: Postovulatory phase fastest (−4.2% vs. Premenstrual, p = 0.008).

- Shooting Consistency (mid-range + long-range): F(4,96) = 5.67; p = 0.003; η2p = 0.19. Post Hoc: Postovulatory +4.7% vs. Menstruation (p = 0.021).

- Defensive Agility and Medicine Ball Throw showed trends toward improvement in the postovulatory phase but did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.062 and p = 0.079, respectively).

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BBT | Basal Body Temperature |

| CLIA | Chemiluminescence Immunoassay |

| E2 | 17β-Estradiol |

| E3G | Estrone-3-Glucuronide |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| FSH | Follicle-Stimulating Hormone |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| IA | Immunoassay |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| ISF | Interstitial Fluid |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| LH | Luteinizing Hormone |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| MC | Menstrual Cycle |

| P4 | Progesterone |

| PdG | Pregnanediol Glucuronide |

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

| TMB | 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Smith, E.S.; McKay, A.K.A.; Kuikman, M.; Ackerman, K.E.; Harris, R.; Elliott-Sale, K.J.; Stellingwerff, T.; Burke, L.M. Auditing the Representation of Female Versus Male Athletes in Sports Science and Sports Medicine Research: Evidence-Based Performance Supplements. Nutrients 2022, 14, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rael, B.; Alfaro-Magallanes, V.M.; Romero-Parra, N.; Castro, E.A.; Cupeiro, R.; Janse de Jonge, X.A.K.; Wehrwein, E.A.; Peinado, A.B. Menstrual Cycle Phases Influence on Cardiorespiratory Response to Exercise in Endurance-Trained Females. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagorna, V.; Mytko, A.; Borysova, O.; Lorenzetti, R.L. Challenges and Opportunities: Addressing Gender Issues in Elite Sports. Phys. Act. Rev. 2025, 13, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyner, M.J.; Hunter, S.K.; Senefeld, J.W. Evidence on sex differences in sports performance. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 138, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokoff, N.J.; Senefeld, J.; Krausz, C.; Hunter, S.; Joyner, M. Sex Differences in Athletic Performance: Perspectives on Transgender Athletes. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2023, 51, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos’Santos, T.; Stebbings, G.K.; Morse, C.; Shashidharan, M.; Daniels, K.A.J.; Sanderson, A. Effects of the menstrual cycle phase on anterior cruciate ligament neuromuscular and biomechanical injury risk surrogates in eumenorrheic and naturally menstruating women: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, M.A.; Thomson, R.L.; Moran, L.J.; Wycherley, T.P. The Impact of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Athletes’ Performance: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.F.; Le, J.; Cui, Y.; Peng, R.; Wang, S.T.; Li, Y. An LC-MS/MS analysis for seven sex hormones in serum. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 162, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channon, R.B.; Nguyen, M.P.; Henry, C.S.; Dandy, D.S. Multilayered Microfluidic Paper-Based Devices: Characterization, Modeling, and Perspectives. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 8966–8972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterton, R.T.; Mateo, E.T., Jr.; Hou, N.; Rademaker, A.W.; Acharya, S.; Jordan, V.C.; Morrow, M. Characteristics of salivary profiles of oestradiol and progesterone in premenopausal women. J. Endocrinol. 2005, 186, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, K.L.; Elliott-Sale, K.J.; Dolan, E.; Swinton, P.A.; Ansdell, P.; Goodall, S.; Thomas, K.; Hicks, K.M. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 1813–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Fortuny, N.; Alonso-Calvete, A.; Da Cuña-Carrera, I.; Abalo-Núñez, R. Menstrual Cycle and Sport Injuries: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, S.F.; Ellison, P.T. Comparison of salivary steroid profiles in naturally occurring conception and non-conception cycles. Hum. Reprod. 1996, 11, 2090–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handelsman, D.J.; Bermon, S. Detection of testosterone doping in female athletes. Drug Test. Anal. 2019, 11, 1566–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meignié, A.; Duclos, M.; Carling, C.; Orhant, E.; Provost, P.; Toussaint, J.F.; Antero, J. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Elite Athlete Performance: A Critical and Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 654585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabre, H.E.; Ladan, A.N.; Moore, S.R.; Joniak, K.E.; Blue, M.N.M.; Pietrosimone, B.G.; Hackney, A.C.; Smith-Ryan, A.E. Effects of Hormonal Contraception and the Menstrual Cycle on Fatigability and Recovery From an Anaerobic Exercise Test. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, 1256–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, A.C. Menstrual Cycle Hormonal Changes and Energy Substrate Metabolism in Exercising Women: A Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivell, R.; Anand-Ivell, R. The Physiology of Reproduction—Quo vadis? Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 650550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, K.K.; Kochanek, J. What place does elite sport have for women? A scoping review of constraints. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1121676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikenfeld, J. Non-invasive analyte access and sensing through eccrine sweat: Challenges and outlook circa 2016. Electroanalysis 2016, 28, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, E.; Andersson, A.; Ekström, L.; Hirschberg, A.L. Urinary Steroid Profile in Elite Female Athletes in Relation to Serum Androgens and in Comparison With Untrained Controls. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 702305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirowatari, Y.; Yoshida, H. Innovatively Established Analysis Method for Lipoprotein Profiles Based on High-Performance Anion-Exchange Liquid Chromatography. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2019, 26, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Gao, W. Non-invasive hormone monitoring with a wearable sweat biosensor. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2025, 3, 190–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Du, X.; Zhang, Z. Advances in electrochemical sensors based on nanomaterials for the detection of lipid hormone. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 993015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashi, T. Salivary hormone measurement using LC/MS/MS: Specific and patient-friendly tool for assessment of endocrine function. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2012, 35, 1401–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inito. Inito Fertility Monitor. 2025. Available online: https://www.inito.com/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Sui, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Cheng, W.; Su, H.; Wang, X.; Sun, X.; Han, X.X.; Zhao, B.; et al. Ultrasensitive detection of thyrotropin-releasing hormone based on azo coupling and surface-enhanced resonance Raman spectroscopy. Analyst 2016, 141, 5181–5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, D.I.; Masitas, R.A.; Thornham, J.; Meng, X.; Steyer, D.J.; Roper, M.G. Droplet-based fluorescence anisotropy insulin immunoassay. Anal. Methods: Adv. Methods Appl. 2024, 16, 7908–7914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batres, G.; Jones, T.; Johnke, H.; Wilson, M.; Holmes, A.E.; Sikich, S. Reactive Arrays of Colorimetric Sensors for Metabolite and Steroid Identification. J. Sens. Technol. 2014, 4, 43398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, J.S.; Ju, H. Ultrahigh-Sensitivity Detection of 17β-Estradiol. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MiraCare. Mira Fertility Tracker. 2025. Available online: https://www.miracare.com/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Drexelius, A.; Kim, S.; Hussain, S.; Heikenfeld, J. Opportunities and limitations of membrane-based preconcentration for rapid and continuous diagnostic applications. Sens. Diagn 2022, 1, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wudy, S.A.; Schuler, G.; Sánchez-Guijo, A.; Hartmann, M.F. The art of measuring steroids: Principles and practice of current hormonal steroid analysis. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 179, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, E.C.; Taylor, J.M.G.; Boonstra, P.S. Modeling basal body temperature data using horseshoe process regression. Stat. Med. 2024, 43, 817–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janse DEJonge, X.; Thompson, B.; Han, A. Methodological Recommendations for Menstrual Cycle Research in Sports and Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 2610–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhlina, L.; Roda, O.; Kalytka, S.; Romaniuk, O.; Matskevych, N.; Zakhozhyi, V. Physical performance during the menstrual cycle of female athletes who specialize in 800 m and 1500 m running. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2016, 16, 1345–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanczyk, F.Z.; Clarke, N.J. Measurement of estradiol-challenges ahead. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Lee, D.Y.; Yu, J.; Lin, Y.N.; Lin, T.M. Recent advances in LC-MS-based metabolomics for clinical biomarker discovery. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2023, 42, 2349–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Wang, M.; Min, J.; Tay, R.Y.; Lukas, H.; Sempionatto, J.R.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Gao, W. A wearable aptamer nanobiosensor for non-invasive female hormone monitoring. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2023, 18, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyachi, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Mieno, E.; Goto, M.; Furusawa, K.; Inagaki, T.; Kitamura, T. Accurate analytical method for human plasma glucagon levels using liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry: Comparison with commercially available immunoassays. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 5911–5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shajari, S.; Kuruvinashetti, K.; Komeili, A.; Sundararaj, U. The Emergence of AI-Based Wearable Sensors for Digital Health Technology: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 9498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameedat, F.; Hawamdeh, S.; Alnabulsi, S.; Zayed, A. High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with Fluorescence Detection for Quantification of Steroids in Clinical, Pharmaceutical, and Environmental Samples: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.E.; Keevil, B.; Huhtaniemi, I.T. Mass spectrometry and immunoassay: How to measure steroid hormones today and tomorrow. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 173, D1–D12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Aria, M.; Erten, A.; Yalcin, O. Technology Advancements in Blood Coagulation Measurements for Point-of-Care Diagnostic Testing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmonds, S.; Heyward, O.; Jones, B. The Challenge of Applying and Undertaking Research in Female Sport. Sports Med.-Open 2019, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZRT Laboratory. Saliva Hormone Testing. 2025. Available online: https://www.zrtlab.com/sample-types/saliva/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, X. Preparation of Graphene Oxide Hydrogels and Their Adsorption Applications toward Various Heavy Metal Ions in Aqueous Media. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, D.R.; Jena, H.M.; Baigenzhenov, O.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A. Graphene-based materials for effective adsorption of organic and inorganic pollutants: A critical and comprehensive review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 160871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.B.; Zhou, J.L. Adsorption of steroid hormones by carbon nanomaterials. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 15970–15984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgin, J.; Franco, D.S.P.; Manzar, M.S.; Meili, L.; El Messaoudi, N. A critical and comprehensive review of the current status of 17β-estradiol hormone remediation through adsorption technology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 24679–24712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, D.P.; Muñoz, R.; Amami, M.; Singh, R.K.; Singh, S.; Kumar, V. Graphene-based materials for biotechnological and biomedical applications: Drug delivery, bioimaging and biosensing. Mater. Today Chem. 2023, 33, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Ma, L.; Jin, Z. Nitrogen-doped graphene: Synthesis, characterizations and energy applications. J. Energy Chem. 2018, 27, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wira, C.; Rodriguez-Garcia, M.; Patel, M. The role of sex hormones in immune protection of the female reproduc-tive tract. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameku, W.A.; Negahdary, M.; Lima, I.S.; Santos, B.G.; Oliveira, T.G.; Paixão, T.R.L.C.; Angnes, L. Laser-Scribed Graphene-Based Electrochemical Sensors: A Review. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jassby, D.; Mandler, D.; Schäfer, A.I. Differentiation of adsorption and degradation in steroid hormone micropollutants removal using electrochemical carbon nanotube membrane. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, M.G. Automatically Signal-Enhanced Lateral Flow Immunoassay for Ultrasensitive Salivary Cortisol Detection. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 2707–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkembi, X.; Botero, M.L.; Skouridou, V.; Jauset-Rubio, M.; Svobodova, M.; Ballester, P.; Bashammakh, A.S.; El-Shahawi, M.S.; Alyoubi, A.O.; O’Sullivan, C.K. Novel nandrolone aptamer for rapid colorimetric detection of anabolic steroids. Anal. Biochem. 2022, 658, 114937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandbakk, Ø.; Solli, G.S.; Holmberg, H.C. Sex Differences in World-Record Performance: The Influence of Sport Discipline and Competition Duration. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo-Pérez, A.; Alejo, L.B.; Valenzuela, P.L.; Gil-Cabrera, J.; Talavera, E.; Luia, A.; Barranco-Gil, D. Traditional Versus Velocity-Based Resistance Training in Competitive Female Cyclists: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 586113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Invasive/Non-Invasive | Pros | Cons | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC (HPLC) with MS/MS) | Invasive (blood samples, interstitial fluid (ISF)) | High accuracy (99% and more), high specificity, multi-hormone profiling | Costly, requires specialized equipment and trained personnel | [25] |

| Immunoassay/Chemiluminescence Immunoassay (ELISA/CLIA) | Invasive (blood samples, interstitial fluid (ISF)); Non-invasive (saliva, urine, sweat) | Simplicity, low cost, requires minimal laboratory conditions, and does not require specialized personnel skills | Lack of specificity, sensitivity, cross-reactivity with other hormones and metabolites, and matrix effects | [28] |

| Optical methods (fluorescence, UV, and Raman spectroscopy) | Invasive (blood samples) | Cost-effective and field-adaptable | Lack precision for quantitative analysis and are susceptible to environmental interference. | [27] |

| Electroanalytical (electrochemical sensors, patches, rings, etc.) | Non-invasive (saliva, urine, sweat) | High accuracy (picomolar range), portable, rapid results, continuous monitoring (via wireless data transmission) | Lower hormone concentrations compared to blood, variability due to saliva flow rates or contamination, concerns about sensor durability during intense physical activity | [27] |

| Day | Activity | Tests Conducted |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | Training + Testing | Acceleration, agility, and strength |

| Tuesday | Training + Testing | Vertical jump, endurance, and technical precision |

| Wednesday | Training + Testing | Agility, power, and sprint analysis |

| Thursday | Training + Testing | Endurance, strength, and movement assessment |

| Friday | Training + Testing | Vertical jump, acceleration, and agility |

| Saturday | Training + Testing | Technical precision, power, endurance |

| Sunday | Rest | None |

| Method | Trademark | Sampling | Accuracy | Fastness | Price (USD) | Simultaneous Estrogen + Progesterone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA/CLIA | Cerascreen | Saliva | 87.50% | 7 days | 100 | ± |

| LC-MS/MS | Walk-In Lab | Saliva | >99% | 7–21 days | 300 | + |

| ELISA/LC-MS | LifeLabs | Blood | 85% | 7–10 days | 80 | + |

| ELISA | Mira | Urine | 99% | 20 min | 260 | − |

| ELISA | Inito | Urine | 99% | 10 min | 150 | − |

| ELISA/CLIA | DRG International | Saliva/blood | 85–90% | 2–4 h | 150–200 | + |

| ELISA/CLIA | IBL International | Saliva/blood | 90–95% | 2–4 h | 200–250 | + |

| ELISA | Abcam | Saliva/blood | 90–95% | 2–4 h | 200–300 | + |

| ELISA | Salimetrics | Saliva | 92–96% | 2–4 h | 180–250 | − |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nagorna, V.; Sencha-Hlevatska, K.; Fehr, D.; Bonmarin, M.; Korobeynikov, G.; Mytko, A.; Lorenzetti, S.R. Advancing Women’s Performance in Fitness and Sports: An Exploratory Field Study on Hormonal Monitoring and Menstrual Cycle-Tailored Training Strategies. Sports 2026, 14, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010007

Nagorna V, Sencha-Hlevatska K, Fehr D, Bonmarin M, Korobeynikov G, Mytko A, Lorenzetti SR. Advancing Women’s Performance in Fitness and Sports: An Exploratory Field Study on Hormonal Monitoring and Menstrual Cycle-Tailored Training Strategies. Sports. 2026; 14(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagorna, Viktoriia, Kateryna Sencha-Hlevatska, Daniel Fehr, Mathias Bonmarin, Georgiy Korobeynikov, Artur Mytko, and Silvio R. Lorenzetti. 2026. "Advancing Women’s Performance in Fitness and Sports: An Exploratory Field Study on Hormonal Monitoring and Menstrual Cycle-Tailored Training Strategies" Sports 14, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010007

APA StyleNagorna, V., Sencha-Hlevatska, K., Fehr, D., Bonmarin, M., Korobeynikov, G., Mytko, A., & Lorenzetti, S. R. (2026). Advancing Women’s Performance in Fitness and Sports: An Exploratory Field Study on Hormonal Monitoring and Menstrual Cycle-Tailored Training Strategies. Sports, 14(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010007