Exploring the Gut Microbiome in Combat Sports: A Systematic Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

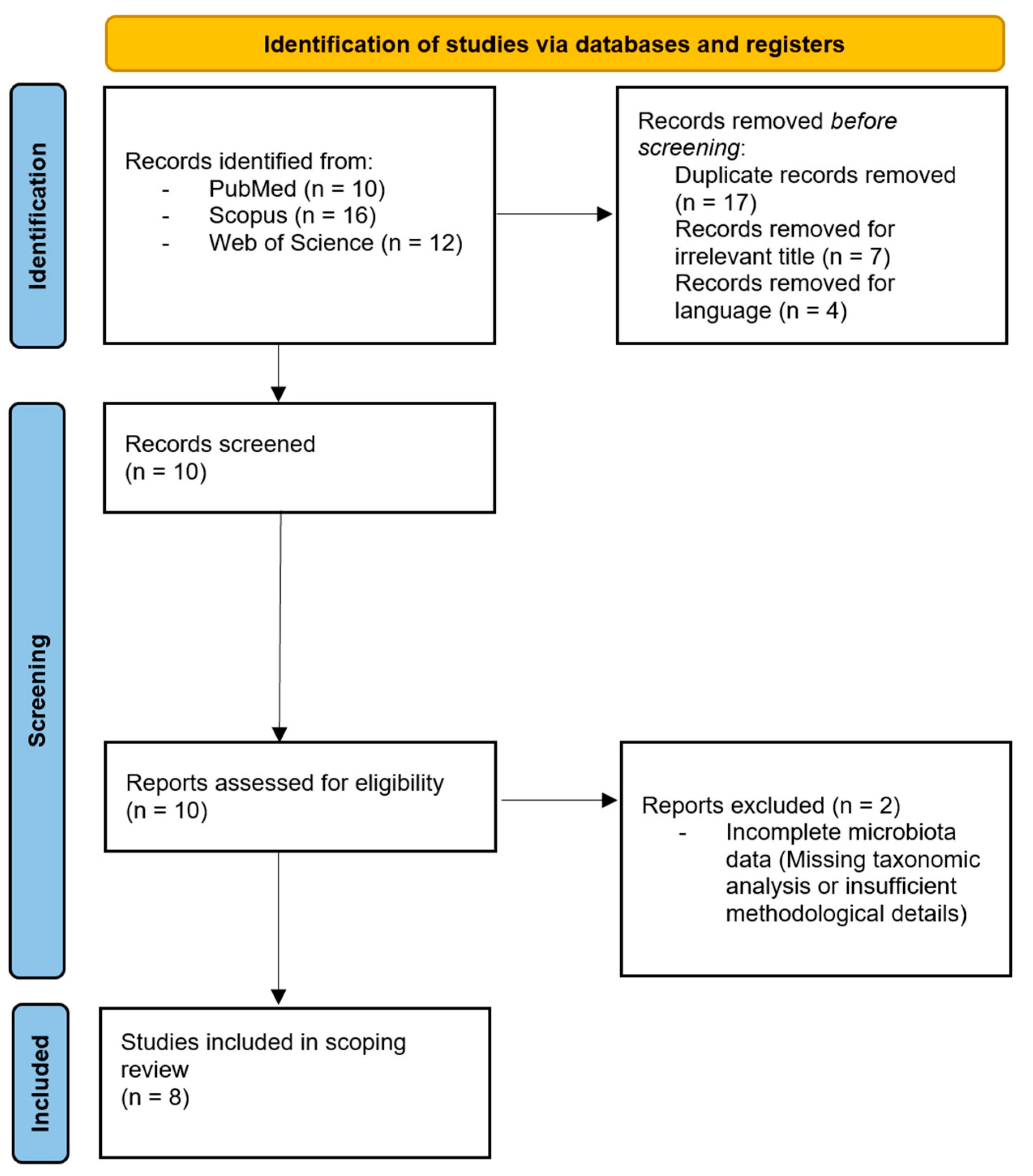

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Research Strategy

2.4. Selection Process, Data Extraction and Analysis

2.5. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

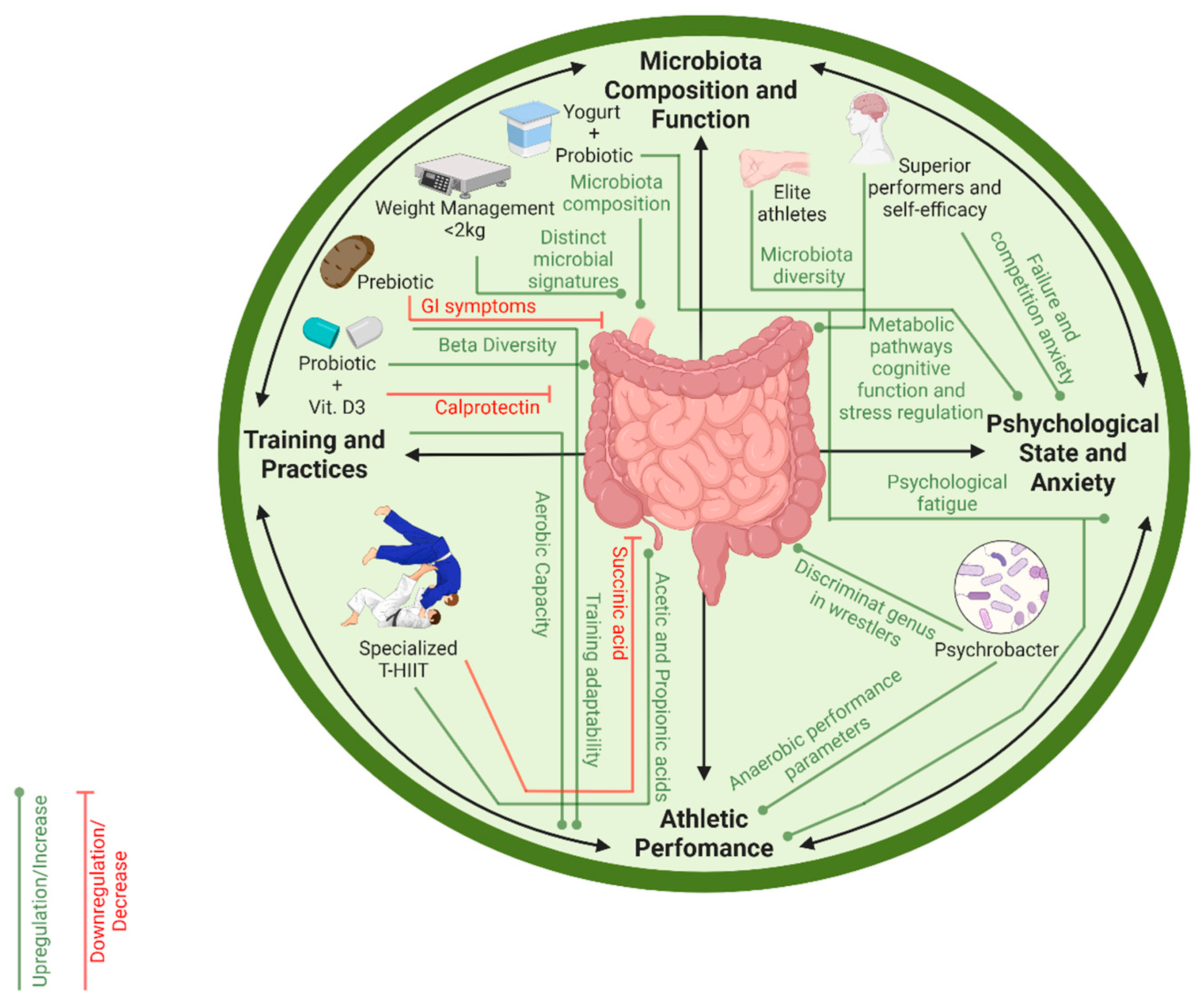

3.2. Microbiome, Athletic Performance and Anxiety

3.3. Weight Control and Microbiome

3.4. Fecal Organic Acid Profile and Performance

3.5. Prebiotic and Probiotic Interventions

4. Discussion

4.1. Sport-Specific Microbial Adaptations

4.2. Inflammation, Gut Barrier and Weight Loss

4.3. Psychological State, Performance and Microbiome

4.4. Sex-Specific Microbiome in Combat Sports

4.5. Dietary Assessment and Standardization in Gut Microbiome Research

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

4.7. Practical Applications and Future Developments

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barley, O.R.; Chapman, D.W.; Guppy, S.N.; Abbiss, C.R. Considerations When Assessing Endurance in Combat Sport Athletes. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rossi, C.; Roklicer, R.; Tubic, T.; Bianco, A.; Gentile, A.; Manojlovic, M.; Maksimovic, N.; Trivic, T.; Drid, P. The Role of Psychological Factors in Judo: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fontana, F.; Longhi, G.; Tarracchini, C.; Mancabelli, L.; Lugli, G.A.; Alessandri, G.; Turroni, F.; Milani, C.; Ventura, M. The human gut microbiome of athletes: Metagenomic and metabolic insights. Microbiome 2023, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Clark, A.; Mach, N. Exercise-induced stress behavior, gut-microbiota-brain axis and diet: A systematic review for athletes. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2016, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O’Donovan, C.M.; Madigan, S.M.; Garcia-Perez, I.; Rankin, A.; O’ Sullivan, O.; Cotter, P.D. Distinct microbiome composition and metabolome exists across subgroups of elite Irish athletes. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, W.; Penney, N.C.; Cronin, O.; Garcia-Perez, I.; Molloy, M.G.; Holmes, E.; Shanahan, F.; Cotter, P.D.; O’Sullivan, O. The microbiome of professional athletes differs from that of more sedentary subjects in composition and particularly at the functional metabolic level. Gut 2018, 67, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, A. The Physiology of Hunger. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, A. Zonulin, regulation of tight junctions, and autoimmune diseases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1258, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mohr, A.E.; Jäger, R.; Carpenter, K.C.; Kerksick, C.M.; Purpura, M.; Townsend, J.R.; West, N.P.; Black, K.; Gleeson, M.; Pyne, D.B.; et al. The athletic gut microbiota. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2020, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Patel, B.K.; Patel, K.H.; Lee, C.N.; Moochhala, S. Intestinal Microbiota Interventions to Enhance Athletic Performance—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carlone, J.; Lista, M.; Romagnoli, R.; Sgrò, P.; Piacentini, M.F.; Di Luigi, L. The role of the hormonal profile of constitutional biotypes in the training process. Med. Sport 2023, 76, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, H.; Medlin, S.; Morehen, J.C. The Role of the Gut Microbiome and Probiotics in Sports Performance: A Narrative Review Update. Nutrients 2025, 17, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Przewłócka, K.; Folwarski, M.; Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K.; Kaczor, J.J. Gut-Muscle AxisExists and May Affect Skeletal Muscle Adaptation to Training. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rankin, A.; O’Donovan, C.; Madigan, S.M.; O’Sullivan, O.; Cotter, P.D. ‘Microbes in sport’-The potential role of the gut microbiota in athlete health and performance. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 698–699, Erratum in Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 618. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-097227corr1. PMID: 28432108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carlone, J.; Giampaoli, S.; Alladio, E.; Rosellini, G.; Barni, F.; Salata, E.; Parisi, A.; Fasano, A.; Tessitore, A. Dynamic stability of gut microbiota in elite volleyball athletes: Microbial adaptations during training, competition and recovery. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 7, 1662964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mousavinasab, F.; Karimi, R.; Taheri, S.; Ahmadvand, F.; Sanaaee, S.; Najafi, S.; Halvaii, M.S.; Haghgoo, A.; Zamany, M.; Majidpoor, J.; et al. Microbiome modulation in inflammatory diseases: Progress to microbiome genetic engineering. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, J.; O’Toole, P.W. Disease-associated microbiome signature species in the gut. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3, pgae352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vargas, A.; Robinson, B.L.; Houston, K.; Vilela Sangay, A.R.; Saadeh, M.; D’Souza, S.; Johnson, D.A. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites and chronic inflammatory diseases. Explor. Med. 2025, 6, 1001275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimer, M.; Teschler, M.; Schmitz, B.; Mooren, F.C. Health Benefits of Probiotics in Sport and Exercise—Non-existent or a Matter of Heterogeneity? A Systematic Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 804046, Erratum in Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1051918. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.1051918. PMID: 35284446; PMCID: PMC8906887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keohane, D.M.; Woods, T.; O’Connor, P.; Underwood, S.; Cronin, O.; Whiston, R.; O’Sullivan, O.; Cotter, P.; Shanahan, F.; Molloy, M.G.M. Four men in a boat: Ultra-endurance exercise alters the gut microbiome. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2019, 22, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Rocha, A.L.; Teixeira, G.R.; Pinto, A.P.; de Morais, G.P.; Oliveira, L.D.C.; de Vicente, L.G.; da Silva, L.E.C.M.; Pauli, J.R.; Cintra, D.E.; Ropelle, E.R.; et al. Excessive training induces molecular signs of pathologic cardiac hypertrophy. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 8850–8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, G.K.; Wang, L.; Nanavati, J.; Twose, C.; Singh, R.; Mullin, G. Dietary Alteration of the Gut Microbiome and Its Impact on Weight and Fat Mass: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Genes 2018, 9, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhong, Y.; Song, Y.; Artioli, G.G.; Gee, T.I.; French, D.N.; Zheng, H.; Lyu, M.; Li, Y. The Practice of Weight Loss in Combat Sports Athletes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Milovančev, A.; Ilić, A.; Miljković, T.; Petrović, M.; Stojšić Milosavljević, A.; Roklicer, R.; Trivic, T.; Manojlovic, M.; Rossi, C.; Bianco, A.; et al. Cardiac biomarkers alterations in rapid weight loss and high-intensity training in judo athletes: A crossover pilot study. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2024, 64, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukic-Sarkanovic, M.; Roklicer, R.; Trivic, T.; Manojlovic, M.; Gilic, B.; Milovancev, A.; Rossi, C.; Bianco, A.; Carraro, A.; Cvjeticanin, M.; et al. Acute muscle damage as a metabolic response to rapid weight loss in wrestlers. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 2024, 16, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roklicer, R.; Rossi, C.; Bianco, A.; Štajer, V.; Maksimovic, N.; Manojlovic, M.; Gilic, B.; Trivic, T.; Drid, P. Rapid weight loss coupled with sport-specific training impairs heart rate recovery in Greco-Roman wrestlers. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimovic, N.; Cvjeticanin, O.; Rossi, C.; Manojlovic, M.; Roklicer, R.; Bianco, A.; Carraro, A.; Sekulic, D.; Milovancev, A.; Trivic, T.; et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its association with rapid weight loss among former elite combat sports athletes in Serbia. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nechalová, L.; Bielik, V.; Hric, I.; Babicová, M.; Baranovičová, E.; Grendár, M.; Koška, J.; Penesová, A. Gut microbiota and metabolic responses to a 12-week caloric restriction combined with strength and HIIT training in patients with obesity: A randomized trial. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Clarke, S.F.; Murphy, E.F.; O’Sullivan, O.; Lucey, A.J.; Humphreys, M.; Hogan, A.; Hayes, P.; O’Reilly, M.; Jeffery, I.B.; Wood-Martin, R.; et al. Exercise and associated dietary extremes impact on gut microbial diversity. Gut 2014, 63, 1913–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancin, L.; Burke, L.M.; Rollo, I. Fibre: The Forgotten Carbohydrate in Sports Nutrition Recommendations. Sports Med. 2025, 55, 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hughes, R.L.; Holscher, H.D. Fueling Gut Microbes: A Review of the Interaction between Diet, Exercise, and the Gut Microbiota in Athletes. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 2190–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Contreras, F.; Al-Najim, W.; le Roux, C.W. Health Benefits Beyond the Scale: The Role of Diet and Nutrition During Weight Loss Programmes. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheng, S.C.; Chang, C.; Chen, Y.C.; Gojobori, T.; Chiu, P.K. Human gut microbiome determining athletes’ performance: An insight from genomic analysis. Ecol. Genet. Genom. 2025, 34, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursell, L.K.; Metcalf, J.L.; Parfrey, L.W.; Knight, R. Defining the human microbiome. Nutr Rev. 2012, 70, S38–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arumugam, M.; Raes, J.; Pelletier, E.; Le Paslier, D.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Tap, J.; Bruls, T.; Batto, J.M. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011, 473, 174–180, Erratum in Nature 2011, 474, 666. Erratum in Nature 2014, 506, 516. PMID: 21508958; PMCID: PMC3728647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, A. All disease begins in the (leaky) gut: Role of zonulin-mediated gut permeability in the pathogenesis of some chronic inflammatory diseases. F1000Res 2020, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fasano, A. Intestinal permeability and its regulation by zonulin: Diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 1096–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marttinen, M.; Ala-Jaakkola, R.; Laitila, A.; Lehtinen, M.J. Gut Microbiota, Probiotics and Physical Performance in Athletes and Physically Active Individuals. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jäger, R.; Mohr, A.E.; Carpenter, K.C.; Kerksick, C.M.; Purpura, M.; Moussa, A.; Townsend, J.R.; Lamprecht, M.; West, N.P.; Black, K.; et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: Probiotics. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2019, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marchesi, J.R.; Adams, D.H.; Fava, F.; Hermes, G.D.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Hold, G.; Quraishi, M.N.; Kinross, J.; Smidt, H.; Tuohy, K.M.; et al. The gut microbiota and host health: A new clinical frontier. Gut 2016, 65, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dallas, D.C.; Sanctuary, M.R.; Qu, Y.; Khajavi, S.H.; Van Zandt, A.E.; Dyandra, M.; Frese, S.A.; Barile, D.; German, J.B. Personalizing protein nourishment. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3313–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Donati Zeppa, S.; Agostini, D.; Gervasi, M.; Annibalini, G.; Amatori, S.; Ferrini, F.; Sisti, D.; Piccoli, G.; Barbieri, E.; Sestili, P.; et al. Mutual Interactions among Exercise, Sport Supplements and Microbiota. Nutrients 2019, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Turnagöl, H.H.; Koşar, Ş.N.; Güzel, Y.; Aktitiz, S.; Atakan, M.M. Nutritional Considerations for Injury Prevention and Recovery in Combat Sports. Nutrients 2021, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu, Y.; Zhong, F.; Zheng, X.; Lai, H.Y.; Wu, C.; Huang, C. Disparity of Gut Microbiota Composition Among Elite Athletes and Young Adults With Different Physical Activity Independent of Dietary Status: A Matching Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 843076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, K.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Weng, X.; Luo, J.; Li, Y.; Mao, Y.H. Dietary Patterns, Gut Microbiota and Sports Performance in Athletes: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oami, T.; Shimazui, T.; Yumoto, T.; Otani, S.; Hayashi, Y.; Coopersmith, C.M. Gut integrity in intensive care: Alterations in host permeability and the microbiome as potential therapeutic targets. J. Intensive Care 2025, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, H.; Forslund, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, G. Human Gut Microbiome Researches Over the Last Decade: Current Challenges and Future Directions. Phenomics 2023, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Song, G. Effects of konjac glucomannan on gastrointestinal symptoms and gut microbiota in athletes with functional constipation: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2025, 64, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przewłócka, K.; Folwarski, M.; Kaczmarczyk, M.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K.; Palma, J.; Bytowska, Z.K.; Kujach, S.; Kaczor, J.J. Combined probiotics with vitamin D3 supplementation improved aerobic performance and gut microbiome composition in mixed martial arts athletes. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1256226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Song, G. Effect of Probiotic Yogurt Supplementation(Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis BB-12) on Gut Microbiota of Female Taekwondo Athletes and Its Relationship with Exercise-Related Psychological Fatigue. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fu, P.; Wang, C.; Zheng, S.; Qiao, L.; Gao, W.; Gong, L. Connection of pre-competition anxiety with gut microbiota and metabolites in wrestlers with varying sports performances based on brain-gut axis theory. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Y.; Cheng, M.; Zha, Y.; Yang, K.; Tong, Y.; Wang, S.; Lu, Q.; Ning, K. Gut microbiota and inflammation patterns for specialized athletes: A multi-cohort study across different types of sports. mSystems 2023, 8, e0025923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liang, R.; Zhang, S.; Peng, X.; Yang, W.; Xu, Y.; Wu, P.; Chen, J.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, J. Characteristics of the gut microbiota in professional martial arts athletes: A comparison between different competition levels. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fu, P.; Wang, C.; Zheng, S.; Gong, L. Differences in gut microbiota and metabolites between wrestlers with varying precompetition weight control effect. Physiol. Genom. 2024, 56, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Sakai, A.; Kuno, T.; Nimura, Y.; Matsunami, H. Impact of Fecal Organic Acid Profile Before Training on Athletic Performance Improvement After High-Intensity Interval Training. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2024, 20, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheiman, J.; Luber, J.M.; Chavkin, T.A.; MacDonald, T.; Tung, A.; Pham, L.D.; Wibowo, M.C.; Wurth, R.C.; Punthambaker, S.; Tierney, B.T.; et al. Meta-omics analysis of elite athletes identifies a performance-enhancing microbe that functions via lactate metabolism. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wohlgemuth, K.J.; Arieta, L.R.; Brewer, G.J.; Hoselton, A.L.; Gould, L.M.; Smith-Ryan, A.E. Sex differences and considerations for female specific nutritional strategies: A narrative review. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koutoukidis, D.A.; Jebb, S.A.; Zimmerman, M.; Otunla, A.; Henry, J.A.; Ferrey, A.; Schofield, E.; Kinton, J.; Aveyard, P.; Marchesi, J.R. The association of weight loss with changes in the gut microbiota diversity, composition, and intestinal permeability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2020068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carías Domínguez, A.M.; de Jesús Rosa Salazar, D.; Stefanolo, J.P.; Cruz Serrano, M.C.; Casas, I.C.; Zuluaga Peña, J.R. Intestinal Dysbiosis: Exploring Definition, Associated Symptoms, and Perspectives for a Comprehensive Understanding—A Scoping Review. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumar, A.; Pramanik, J.; Goyal, N.; Chauhan, D.; Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Prajapati, B.G.; Chaiyasut, C. Gut Microbiota in Anxiety and Depression: Unveiling the Relationships and Management Options. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xiong, R.G.; Li, J.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, D.D.; Wu, S.X.; Huang, S.Y.; Saimaiti, A.; Yang, Z.J.; Gan, R.Y.; Li, H.B. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Anxiety, Depression, and Other Mental Disorders as Well as the Protective Effects of Dietary Components. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, T.; Liu, F.; Huang, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Qian, Y.; Zhou, W. Influence of gut microbiota on resilience and its possible mechanisms. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 2588–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dalton, A.; Mermier, C.; Zuhl, M. Exercise influence on the microbiome-gut-brain axis. Gut Microbes 2019, 10, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, Y.S.; Unno, T.; Kim, B.Y.; Park, M.S. Sex differences in gut microbiota. World J. Men Health 2020, 38, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markle, J.G.M.; Frank, D.N.; Mortin-Toth, S.; Robertson, C.E.; Feazel, L.M.; Rolle-Kampczyk, U.; von Bergen, M.; McCoy, K.D.; Macpherson, A.J.; Danska, J.S. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science 2013, 339, 1084–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Org, E.; Mehrabian, M.; Parks, B.W.; Shipkova, P.; Liu, X.; Drake, T.A.; Lusis, A.J. Sex differences and hormonal effects on gut microbiota composition in mice. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliada, A.; Moseiko, V.; Romanenko, M.; Lushchak, O.; Kryzhanovska, N.; Guryanov, V.; Vaiserman, A. Sex differences in the phylum-level human gut microbiota composition. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, J.N.; Lydon, K.M.; O’Donovan, C.M.; O’Sullivan, O.; Madigan, S.M. More than a gut feeling: What is the role of the gastrointestinal tract in female athlete health? Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2022, 22, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmora, N.; Suez, J.; Elinav, E. You are what you eat: Diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Chang, H.-W.; Yan, D.; Lee, K.M.; Ucmak, D.; Wong, K.; Abrouk, M.; Farahnik, B.; Nakamura, M.; Zhu, T.H.; et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeming, E.R.; Louca, P.; Gibson, R.; Menni, C.; Spector, T.D.; Le Roy, C.I. The complexities of the diet-microbiome relationship: Advances and perspectives. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, F.C.; Patangia, D.; Grimaud, G.; Lavelle, A.; Dempsey, E.M.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. The interplay between diet and the gut microbiome: Implications for health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodziejczyk, A.A.; Zheng, D.; Elinav, E. Diet-microbiota interactions and personalized nutrition. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, C.L.; Weir, T.L. The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science 2018, 362, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, V.; Bimonte, V.M.; Sabato, C.; Paoli, A.; Baldari, C.; Campanella, M.; Lenzi, A.; Ferretti, E.; Migliaccio, S. Nutrition and physical activity-induced changes in gut microbiota: Possible implications for human health and athletic performance. Foods 2021, 10, 3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driuchina, A.; Isola, V.; Hulmi, J.J.; Salmi, V.M.; Hintikka, J.; Ahtiainen, J.P.; Pekkala, S. Unveiling the impact of competition weight loss on gut microbiota: Alterations in diversity, composition, and predicted metabolic functions. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2025, 22, 2474561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, M.A.; Bird, A.R. The impact of diet and lifestyle on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrients 2015, 7, 17–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, A.; Rothschild, J.A.; Santos, H.O.; Hamidvand, A.; Koozehchian, M.S.; Ghazzagh, A.; Berjisian, E.; Podlogar, T. Nutritional strategies to improve post-exercise recovery and subsequent exercise performance: A narrative review. Sports Med. 2025, 55, 1559–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancin, L.; Paoli, A.; Berry, S.; Gonzalez, J.T.; Collins, A.J.; Lizarraga, M.A.; Mota, J.F.; Nicola, S.; Rollo, I. Standardization of gut microbiome analysis in sports. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rodriguez, J.; Hassani, Z.; Alves Costa Silva, C.; Betsou, F.; Carraturo, F.; Fasano, A.; Israelsen, M.; Iyappan, A.; Krag, A.; Metwaly, A.; et al. State of the art and the future of microbiome-based biomarkers: A multidisciplinary Delphi consensus. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlone, J.; Parisi, A.; Fasano, A. The performance gut: A key to optimizing performance in high-level athletes: A systematic scoping review. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 7, 1641923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlone, J.; Giampaoli, S.; Brancucci, A. Interactions between gut microbiota and brain: Possible effects on sport performance. J. Sci. Sport Exerc. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskell, S.; Martinez, I.; Costa, R.J.S. Gut microbiota and exercise: A systematic review of interventions and evidence limitations. Int. J. Sports Med. 2025, 47, 3–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mast, E.E.; Goodman, R.A. Prevention of infectious disease transmission in sports. Sports Med. 1997, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Population | Age | Study Design | Intervention/Protocol | Dietary Assessment Tool | Primary Outcomes | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhu et al. (2025) [51] | Elite Taekwondo Athletes (48 Male) | 22.8 ± 3.3 Years | Double-blind RCT | DG: 3 g KGM daily for 8 weeks; CG: 3 g maltodextrin (Placebo) daily for 8 weeks | Semi-quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire | Gastrointestinal symptoms and gut microbiota composition | Significant improvements observed only in DG: Improved gastrointestinal symptoms, PAC-SYM, PAC-QoL, BMF and BFI. Increased α-diversity and elevated abundances of Prevotella_9, Phascolarctobacterium, Lactobacillus, Bacteroides, Prevotellaceae. Reduced Alistipes and Desulfovibrio. Upregulation of Biotin Biosynthesis I, Nitrate Reduction VI and downregulation of L-methionine Biosynthesis III pathways |

| Fu et al. (2024a) [54] | 12 Elite Wrestling Athletes (6 Male and 6 Female) | 20.0 ± 1.7 Years | Cross-sectional. Observational | Shared diet and training aimed at weight loss | N/A | Pre-competition anxiety, gut microbiota and metabolites | Better performers had more diverse gut microbiota. Lower competition anxiety in high-performance groups. Metabolites in high performance group enriched in metabolism pathways |

| Fu et al. (2024b) [57] | 12 Elite Wrestling Athletes (6 Male and 6 Female) | 20.1 ± 2.0 Years | Observational, Prospective | Dietary and training adaptations for weight control | 24 h Dietary recall × 3 days | Psychological fatigue, gut microbiota and metabolites | Superior weight control linked to better nutrition. Better training adaptation in <2 kg weight loss group. Distinct gut microbiota and metabolic pathways |

| Yoshikawa et al. (2024) [58] | High-level Judo Athletes (10 + 10 Male) | 19.5 ± 1.2 Years | Prospective | Specialized Tabata T-HIIT every 2 days for 4 weeks | N/A | Uchikomi shuttle run performance, fecal organic acids | Improved specialized endurance in judoka. Negative correlation between fecal succinic acid and performance improvements. High-level competitors had different organic acid profiles |

| Li et al. (2023) [55] | High-level Wrestling Athletes (53 male) | 16 ± 4 Years | Multi-cohort; Cross-sectional | Sport-specific training | Generic Dietary Questionnaire (20 measurements) | Gut microbiota, inflammatory markers and body composition | Sport-specific gut microbiota profiles, Prevotella-driven subgroup linked to inflammation. Sex dependent effects of exercise intensity |

| Zhu et al. (2023) [53] | High-level Taekwondo Athletes (51 Female) | 22.3 ± 0.6 Years | RCT | DK: 250 mL probiotic yoghurt (Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis BB-12) daily for 8 weeks; CK: routine training without dietary intervention | Dietary Habits Questionnaire + Yoghurt intake monitoring | Psychological fatigue and gut microbiota | Significant improvements observed only in DK: Improved psychological fatigue recovery. Increased beneficial gut bacteria. Enhanced metabolic pathways |

| Przewłócka et al. (2023) [52] | High-level MMA Athletes (23 Male) | 26.0 ± 4.0 Years | RCT | Group 1: Combined probiotics (Bifidobacterium lactis W51, Levilactobacillus brevis W63, Lactobacillus acidophilus W22, Bifidobacterium bifidum W23, Lactococcus lactis W58) + Vitamin D3; Group 2: Vitamin D3 only for 4 weeks | 3-day Food interview + Food Frequency Questionnaire + Supplements survey | Aerobic performance, gut microbiota composition, intestinal permeability and inflammatory markers | Significant improvements observed only in Group 1: Significantly extended time to exhaustion in VO2max test. Increased β-diversity of gut microbiota. Reduced fecal calprotectin and increased Bacteroides, Roseburia and Prevotella |

| Liang et al. (2019) [56] | 28 High-level Wushu Martial Arts Athletes (13 male and 15 female) | 20/24 Years | Cross-sectional. Observational | Sport-specific training compared between competitive levels | Feces Pre-collection Questionnaire (3-month recall) | Gut microbiota diversity, taxonomic composition, functional metabolism | Higher-level athletes showed significantly higher α-diversity. Enhanced metabolic pathways for histidine and carbohydrate metabolism than lower-level athletes; Parabacteroides correlated with exercise load; Parabacteroides, Phascolarctobacterium, Oscillibacter and Bilophila enriched in higher-level athletes; Megasphaera is abundant in lower-level athletes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Carlone, J.; Rossi, C.; Bianco, A.; Drid, P.; Parisi, A.; Fasano, A. Exploring the Gut Microbiome in Combat Sports: A Systematic Scoping Review. Sports 2026, 14, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010019

Carlone J, Rossi C, Bianco A, Drid P, Parisi A, Fasano A. Exploring the Gut Microbiome in Combat Sports: A Systematic Scoping Review. Sports. 2026; 14(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarlone, Junior, Carlo Rossi, Antonino Bianco, Patrik Drid, Attilio Parisi, and Alessio Fasano. 2026. "Exploring the Gut Microbiome in Combat Sports: A Systematic Scoping Review" Sports 14, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010019

APA StyleCarlone, J., Rossi, C., Bianco, A., Drid, P., Parisi, A., & Fasano, A. (2026). Exploring the Gut Microbiome in Combat Sports: A Systematic Scoping Review. Sports, 14(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010019