Training Practices Among Spanish Natural Elite Bodybuilders in the Pre-Contest Phase

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Variables and Instruments

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van der Ploeg, G.E.; Brooks, A.G.; Withers, R.T.; Dollman, J.; Leaney, F.; Chatterton, B.E. Body Composition Changes in Female Bodybuilders during Preparation for Competition. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 55, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossow, L.M.; Fukuda, D.H.; Fahs, C.A.; Loenneke, J.P.; Stout, J.R. Natural Bodybuilding Competition Preparation and Recovery: A 12-Month Case Study. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2013, 8, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, E.R.; Aragon, A.A.; Fitschen, P.J. Evidence-Based Recommendations for Natural Bodybuilding Contest Preparation: Nutrition and Supplementation. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2014, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, A.J.; Simper, T.; Helms, E. Nutritional Strategies of British Professional and Amateur Natural Bodybuilders during Competition Preparation. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2019, 16, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). International Standard for the Testing and Investigations (ISTI)—Guidelines for Implementing an Effective Testing Program. 2021. Available online: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/resources/world-anti-doping-program/guidelines-implementing-effective-testing-program (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- González Cano, H.; Jiménez Martínez, P.; Baz Valle, E.; Contreras, C.; Colado Sánchez, J.C.; Alix Fages, C. Nutritional and Supplementation Strategies of Spanish Natural Elite Bodybuilders in Precontest. Gazz. Med. Ital. 2023, 181, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, E.R.; Fitschen, P.J.; Aragon, A.A.; Cronin, J.; Schoenfeld, B.J. Recommendations for Natural Bodybuilding Contest Preparation: Resistance and Cardiovascular Training. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2015, 55, 164–178. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Martínez, P.; Ramirez Campillo, R.; Flandez, J.; Alix Fages, C.; Baz Valle, E.; Colado Sánchez, J.C. Effects of Oral Capsaicinoids and Capsinoids Supplementation on Resistance and High Intensity Interval Training: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2023, 18, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, A.J.; Simper, T.; Barker, M.E. Nutritional Strategies of High Level Natural Bodybuilders during Competition Preparation. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2018, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistler, B.M.; Fitschen, P.J.; Ranadive, S.M.; Fernhall, B.; Wilund, K.R. Case Study: Natural Bodybuilding Contest Preparation. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014, 24, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.; Fisher, J.; Grgic, J.; Haun, C.; Helms, E.; Phillips, S.; Steele, J.; Vigotsky, A. Resistance Training Recommendations to Maximize Muscle Hypertrophy in an Athletic Population: Position Stand of the IUSCA. Int. J. Strength Cond. 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baz-Valle, E.; Balsalobre-Fernández, C.; Alix-Fages, C.; Santos-Concejero, J. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Different Resistance Training Volumes on Muscle Hypertrophy. J. Hum. Kinet. 2022, 81, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Fernández, C.; Muñoz-López, M.; Marchante, D.; García-Ramos, A. Repetitions in Reserve and Rate of Perceived Exertion Increase the Prediction Capabilities of the Load-Velocity Relationship. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, E.R.; Cronin, J.; Storey, A.; Zourdos, M.C. Application of the Repetitions in Reserve-Based Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale for Resistance Training. Strength Cond. J. 2016, 38, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human participants. JAMA 2025, 333, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Davies, T.B.; Hackett, D.A. Self-Reported Training and Supplementation Practices between Performance-Enhancing Drug-User Bodybuilders Compared with Natural Bodybuilders. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2023, 37, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackett, D.A. Training, Supplementation, and Pharmacological Practices of Competitive Male Bodybuilders across Training Phases. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-8058-0283-2. [Google Scholar]

- Akoglu, H. User’s Guide to Correlation Coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Martínez, P.; Alix-Fages, C.; Helms, E.R.; Espinar, S.; González-Cano, H.; Baz-Valle, E.; Janicijevic, D.; García-Ramos, A.; Colado, J.C. Dietary Supplementation Habits in International Natural Bodybuilders during Pre-Competition. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMenichi, B.C.; Tricomi, E. The Power of Competition: Effects of Social Motivation on Attention, Sustained Physical Effort, and Learning. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currier, B.S.; Mcleod, J.C.; Banfield, L.; Beyene, J.; Welton, N.J.; D’Souza, A.C.; Keogh, J.A.J.; Lin, L.; Coletta, G.; Yang, A.; et al. Resistance Training Prescription for Muscle Strength and Hypertrophy in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J.; Grgic, J.; Krieger, J. How Many Times per Week Should a Muscle Be Trained to Maximize Muscle Hypertrophy? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Examining the Effects of Resistance Training Frequency. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 1286–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, R.M.; Roschel, H.; Tricoli, V.; de Souza, E.O.; Wilson, J.M.; Laurentino, G.C.; Aihara, A.Y.; de Souza Leão, A.R.; Ugrinowitsch, C. Changes in Exercises Are More Effective than in Loading Schemes to Improve Muscle Strength. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 3085–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, B.D.d.V.; Kassiano, W.; Nunes, J.P.; Kunevaliki, G.; Castro-E-Souza, P.; Rodacki, A.; Cyrino, L.T.; Cyrino, E.S.; Fortes, L.d.S. Does Performing Different Resistance Exercises for the Same Muscle Group Induce Non-Homogeneous Hypertrophy? Int. J. Sports Med. 2021, 42, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabaleta-Korta, A.; Fernández-Peña, E.; Santos-Concejero, J.; Zabaleta-Korta, A.; Fernández-Peña, E.; Santos-Concejero, J. Regional Hypertrophy, the Inhomogeneous Muscle Growth: A Systematic Review. Strength Cond. J. 2020, 42, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassiano, W.; Nunes, J.P.; Costa, B.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Cyrino, E.S. Does Varying Resistance Exercises Promote Superior Muscle Hypertrophy and Strength Gains? A Systematic Review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 1753–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baz-Valle, E.; Fontes-Villalba, M.; Santos-Concejero, J. Total Number of Sets as a Training Volume Quantification Method for Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J.; Grgic, J.; Haun, C.; Itagaki, T.; Helms, E.R. Calculating Set-Volume for the Limb Muscles with the Performance of Multi-Joint Exercises: Implications for Resistance Training Prescription. Sports 2019, 7, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enes, A.; Correa, C.L.; Bernardo, M.F.; Salles, G.N.; Oneda, G.; Leonel, D.F.; Fleck, S.J.; Phillips, S.M.; De Souza, E.O.; Souza-Junior, T.P. Does Increasing the Resistance-Training Volume Lead to Greater Gains? The Effects of Weekly Set Progressions on Muscular Adaptations in Females. J. Sports Sci. 2025, 43, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enes, A.; DE Souza, E.O.; Souza-Junior, T.P. Effects of Different Weekly Set Progressions on Muscular Adaptations in Trained Males: Is There a Dose-Response Effect? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2024, 56, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aube, D.; Wadhi, T.; Rauch, J.; Anand, A.; Barakat, C.; Pearson, J.; Bradshaw, J.; Zazzo, S.; Ugrinowitsch, C.; De Souza, E.O. Progressive Resistance Training Volume: Effects on Muscle Thickness, Mass, and Strength Adaptations in Resistance-Trained Individuals. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelland, J.; Remmert, J.; Robinson, Z.; Hinson, S.; Zourdos, M. The Resistance Training Dose-Response: Meta-Regressions Exploring the Effects of Weekly Volume and Frequency on Muscle Hypertrophy and Strength Gains. Sports Med. 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, G.; Mendiguchía, J.; Alomar, X.; Padullés, J.M.; Serrano, D.; Nescolarde, L.; Rodas, G.; Cussó, R.; Balius, R.; Cadefau, J.A. Time Course and Association of Functional and Biochemical Markers in Severe Semitendinosus Damage Following Intensive Eccentric Leg Curls: Differences between and within Subjects. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeo, S.; Huang, M.; Wu, Y.; Sakurai, H.; Kusagawa, Y.; Sugiyama, T.; Kanehisa, H.; Isaka, T. Greater Hamstrings Muscle Hypertrophy but Similar Damage Protection after Training at Long versus Short Muscle Lengths. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2021, 53, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.; Grgic, J. Evidence-Based Guidelines for Resistance Training Volume to Maximize Muscle Hypertrophy. Strength Cond. J. 2018, 40, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J.; Androulakis-Korakakis, P.; Piñero, A.; Burke, R.; Coleman, M.; Mohan, A.E.; Escalante, G.; Rukstela, A.; Campbell, B.; Helms, E. Alterations in Measures of Body Composition, Neuromuscular Performance, Hormonal Levels, Physiological Adaptations, and Psychometric Outcomes during Preparation for Physique Competition: A Systematic Review of Case Studies. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2023, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardue, A.; Trexler, E.T.; Sprod, L.K. Case Study: Unfavorable but Transient Physiological Changes during Contest Preparation in a Drug-Free Male Bodybuilder. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2017, 27, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, V.; Hulmi, J.J.; Mbay, T.; Kyröläinen, H.; Häkkinen, K.; Ahola, V.; Helms, E.R.; Ahtiainen, J.P. Changes in Hormonal Profiles during Competition Preparation in Physique Athletes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 125, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J.; Grgic, J.; Ogborn, D.; Krieger, J.W. Strength and Hypertrophy Adaptations between Low- vs. High-Load Resistance Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 3508–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgic, J. The Effects of Low-Load vs. High-Load Resistance Training on Muscle Fiber Hypertrophy: A Meta-Analysis. J. Hum. Kinet. 2020, 74, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.P.; Steele, J. Heavier and Lighter Load Resistance Training to Momentary Failure Produce Similar Increases in Strength with Differing Degrees of Discomfort. Muscle Nerve 2017, 56, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Level | Body Builders | Men’s Physique | Sig. | φ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Amateurs (n = 27) | 16 (59.3%) | 11 (40.7%) | 0.102 | 0.22 | |||

| Professionals (n = 29) | 10 (37%) | 17 (63%) | ||||||

| Total (n = 56) * | 26 (46.4%) | 28 (50%) | ||||||

| Variable | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mode | Sig. | Cohen’s d | |

| Age (years) | Amateurs | 28.61 | 5.66 | 27.0 | 4.75 | 26 | 0.487 | 0.06 |

| Professionals | 28.64 | 4.07 | 28.5 | 5 | 27 | |||

| Training experience (years) | Amateurs | 7.85 | 3.71 | 8 | 4.5 | 5 | 0.163 | 0.29 |

| Professionals | 8.90 | 3.61 | 8 | 6.0 | 6 | |||

| Competing experience (years) | Amateurs | 3.07 | 2.32 | 2 | 2.5 | 2 | 0.078 | 0.49 |

| Professionals | 4.34 | 2.84 | 4 | 3.0 | 3 | |||

| Competitions in the previous year | Amateurs | 2.70 | 1.10 | 3 | 1.0 | 2 | 0.809 | 0.15 |

| Professionals | 2.55 | 0.87 | 3 | 1.0 | 3 | |||

| Weeks on diet | Amateurs | 28.90 | 6.26 | 28.5 | 6.5 | 28 | 0.488 | 0.19 |

| Professionals | 27.30 | 10.60 | 27.0 | 12.3 | 20 | |||

| Weight change (kg) | Amateurs | −14.50 | 4.59 | −14.0 | 3.0 | −13 | 0.185 | 0.30 |

| Professionals | −11.90 | 11.30 | −13.0 | 6.5 | −13 | |||

| Variable | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mode | Sig. | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training sessions/week | Amateurs | 4.74 | 0.45 | 5 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.506 | 0.19 |

| Professionals | 4.83 | 0.47 | 5 | 0 | 5 | |||

| Chest trainings/week | Amateurs | 1.85 | 0.46 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.645 | 0.14 |

| Professionals | 1.79 | 0.41 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| Back trainings/week | Amateurs | 1.93 | 0.39 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.140 | 0.40 |

| Professionals | 1.76 | 0.44 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| Quads trainings/week | Amateurs | 1.70 | 0.47 | 2 | 1.0 | 2 | 0.516 | 0.17 |

| Professionals | 1.62 | 0.49 | 2 | 1.0 | 2 | |||

| Biceps trainings/week | Amateurs | 1.96 | 0.34 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.574 | 0.06 |

| Professionals | 1.93 | 0.70 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| Triceps trainings/week | Amateurs | 1.96 | 0.34 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.559 | 0.06 |

| Professionals | 1.93 | 0.65 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| Hamstrings trainings/week | Amateurs | 1.78 | 0.51 | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.385 | 0.25 |

| Professionals | 1.66 | 0.48 | 2 | 1.0 | 2 | |||

| Shoulder trainings/week | Amateurs | 2.22 | 0.58 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.939 | 0.03 |

| Professionals | 2.24 | 0.79 | 2 | 1.0 | 2 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mode | Sig. | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest exercises/week | Amateurs | 4.33 | 1.47 | 5 | 2.0 | 5 | 0.235 | 0.43 |

| Professionals | 4.97 | 1.48 | 4 | 2.0 | 4 | |||

| Back exercises/week | Amateurs | 5.70 | 1.66 | 6 | 2.0 | 6 | 0.287 | 0.34 |

| Professionals | 6.24 | 1.46 | 6 | 3.0 | 8 | |||

| Quads exercises/week | Amateurs | 4.04 | 1.60 | 4 | 2.5 | 5 | 0.913 | 0.02 |

| Professionals | 4.07 | 1.41 | 4 | 2.0 | 4 | |||

| Hamstrings exercises/week | Amateurs | 3.56 | 1.40 | 4 | 1.0 | 4 | 0.502 | 0.17 |

| Professionals | 3.34 | 1.01 | 3 | 1.0 | 3 | |||

| Shoulders exercises/week | Amateurs | 4.74 | 1.77 | 4 | 2.0 | 4 | 0.822 | 0.07 |

| Professionals | 4.86 | 1.92 | 5 | 3.0 | 4 | |||

| Biceps exercises/week | Amateurs | 3.48 | 0.94 | 3 | 1.0 | 3 | 0.467 | 0.29 |

| Professionals | 3.83 | 1.39 | 4 | 2.0 | 3 | |||

| Triceps exercises/week | Amateurs | 3.42 | 0.90 | 3 | 1.0 | 3 | 0.317 | 0.36 |

| Professionals | 3.83 | 1.31 | 4 | 2.0 | 3 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mode | Sig. | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

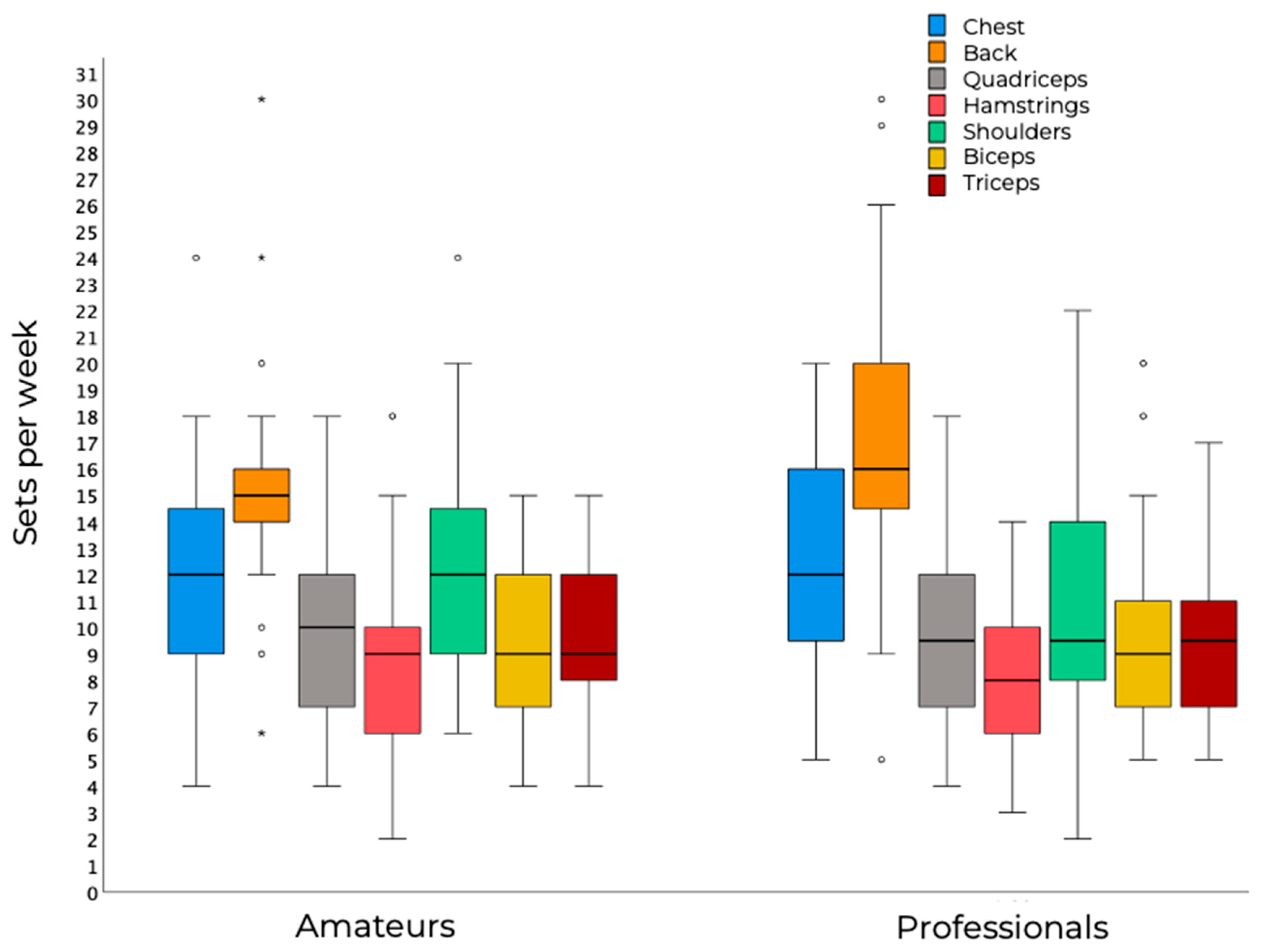

| Chest sets/week | Amateurs | 11.80 | 4.40 | 12 | 5.5 | 12 | 0.479 | 0.22 |

| Professionals | 12.70 | 4.22 | 12 | 6.0 | 12 | |||

| Back sets/week | Amateurs | 15.30 | 4.44 | 15 | 2.0 | 15 | 0.126 | 0.33 |

| Professionals | 17.00 | 5.41 | 16 | 5.3 | 20 | |||

| Quads sets/week | Amateurs | 10.00 | 3.69 | 10 | 5.0 | 6 | 0.980 | 0.02 |

| Professionals | 9.97 | 3.59 | 10 | 5.0 | 12 | |||

| Hamstrings sets/week | Amateurs | 8.56 | 3.46 | 9 | 4.0 | 9 | 0.519 | 0.14 |

| Professionals | 8.10 | 2.90 | 8 | 4.0 | 8 | |||

| Shoulder sets/week | Amateurs | 12.00 | 4.28 | 12 | 5.5 | 12 | 0.338 | 0.18 |

| Professionals | 11.20 | 5.47 | 10 | 6.0 | 9 | |||

| Biceps sets/week | Amateurs | 9.04 | 2.94 | 9 | 5.0 | 8 | 0.845 | 0.15 |

| Professionals | 9.54 | 3.82 | 9 | 3.5 | 10 | |||

| Triceps sets/week | Amateurs | 9.11 | 2.61 | 9 | 4.0 | 9 | 0.667 | 0.17 |

| Professionals | 9.62 | 3.26 | 10 | 4.0 | 10 | |||

| Sets per exercise | Amateurs | 2.89 | 0.70 | 3 | 1.0 | 3 | 0.101 | 0.50 |

| Professionals | 2.59 | 0.50 | 3 | 1.0 | 3 | |||

| 1–5 reps | 6–10 reps | 11–15 reps | >15 reps | Mode | Sig. | Cramer’s V | ||

| Most used repetition range | Amateurs | 0% | 74.1% | 25.9% | 0% | 6–10 | 0.128 | 0.20 |

| Professionals | 0% | 89.7% | 10.3% | 0% | 6–10 | |||

| Second most used repetition range | Amateurs | 14.8% | 33.3% | 51.9% | 0% | 11–15 | 0.525 | 0.15 |

| Professionals | 13.8% | 20.7% | 65.5% | 0% | 11–15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Baz-Valle, E.; Martínez-Gómez, S.; Gene-Morales, J.; Jiménez-Martínez, P.; Alix-Fages, C.; Santos-Concejero, J. Training Practices Among Spanish Natural Elite Bodybuilders in the Pre-Contest Phase. Sports 2026, 14, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010020

Baz-Valle E, Martínez-Gómez S, Gene-Morales J, Jiménez-Martínez P, Alix-Fages C, Santos-Concejero J. Training Practices Among Spanish Natural Elite Bodybuilders in the Pre-Contest Phase. Sports. 2026; 14(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaz-Valle, Eneko, Sergio Martínez-Gómez, Javier Gene-Morales, Pablo Jiménez-Martínez, Carlos Alix-Fages, and Jordan Santos-Concejero. 2026. "Training Practices Among Spanish Natural Elite Bodybuilders in the Pre-Contest Phase" Sports 14, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010020

APA StyleBaz-Valle, E., Martínez-Gómez, S., Gene-Morales, J., Jiménez-Martínez, P., Alix-Fages, C., & Santos-Concejero, J. (2026). Training Practices Among Spanish Natural Elite Bodybuilders in the Pre-Contest Phase. Sports, 14(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010020