Analysis of Basketball Referee Decision-Making Using the DMQ-II Questionnaire

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

- Factor 1. Stress in decision-making

- Factor 2. Rapid decision-making under uncertainty

- Factor 3. Determination and commitment in decision-making

2.3. Statistical Analysis

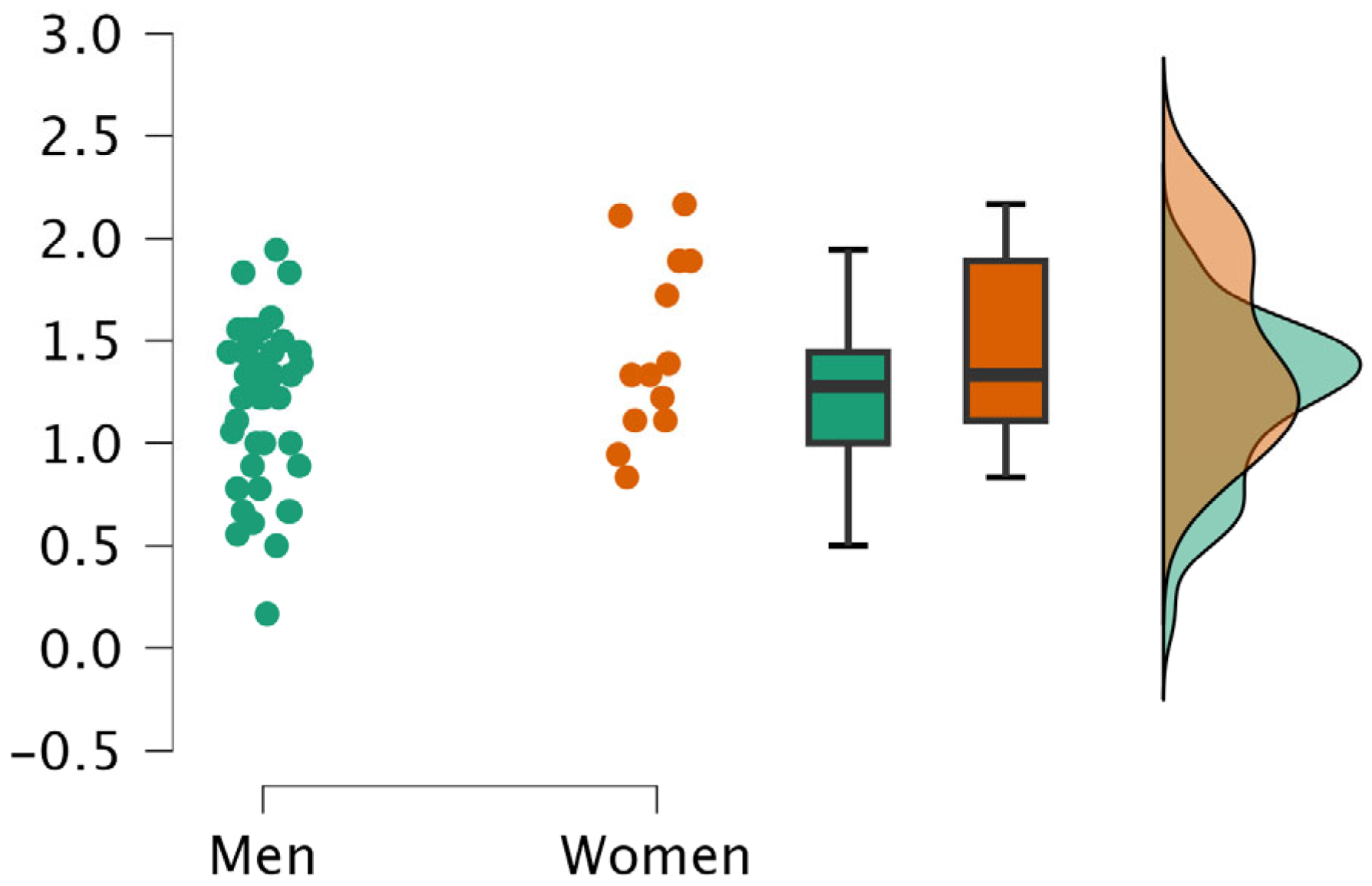

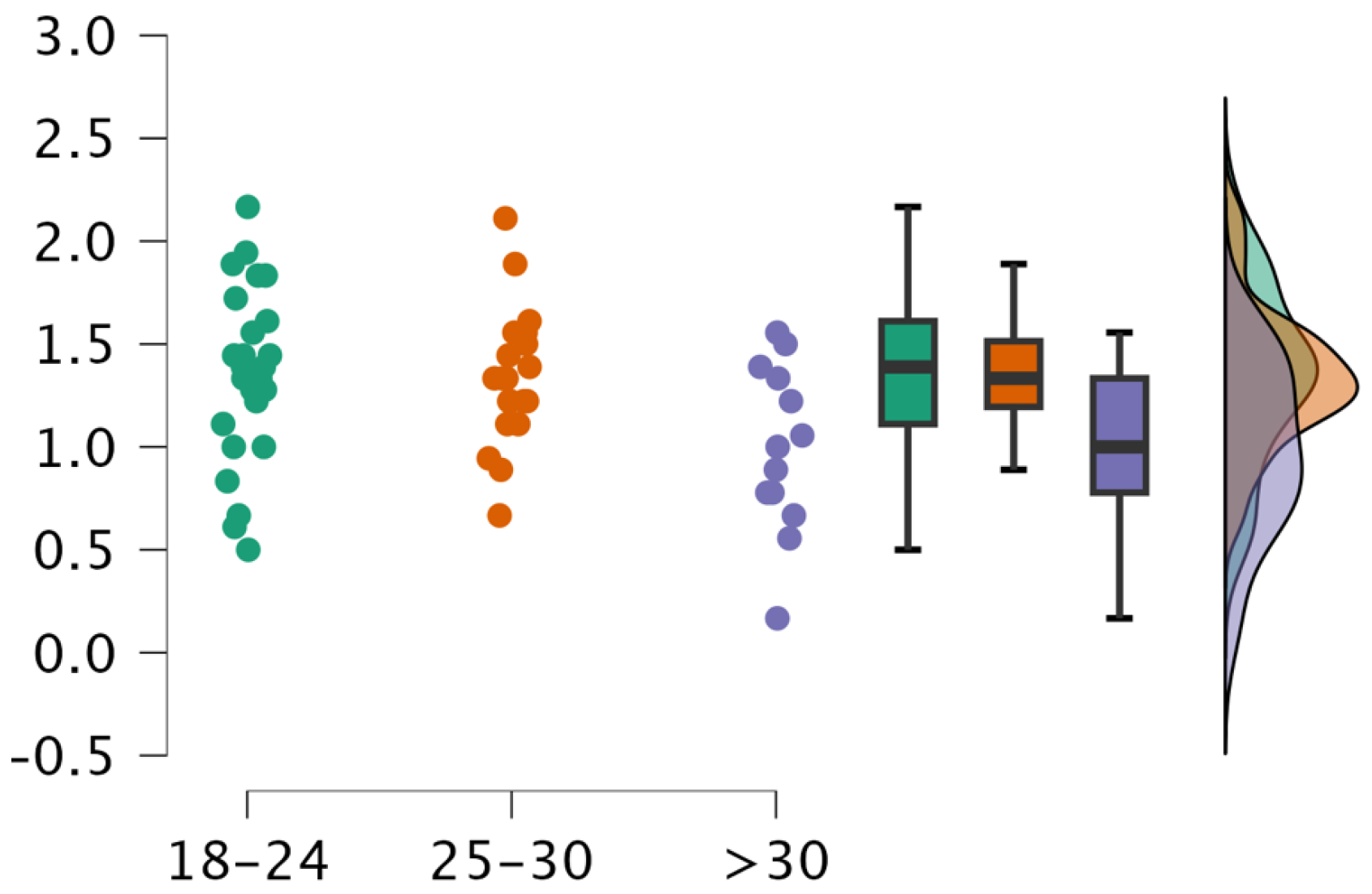

3. Results

4. Discussion

Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bustos, J.D. Competency-Based Curriculum Design for the Training of Basketball Referees. Master’s Thesis, National Pedagogical University of Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Philippe, F.L.; Vallerand, R.J.; Andrianarisoa, J.; Brunel, P. Passion in Referees: Examining Their Affective and Cognitive Experiences in Sport Situations. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2009, 31, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aginsky, K.D. Why It Is Difficult to Detect an Illegally Bowled Cricket Delivery with Either the Naked Eye or Usual Two-Dimensional Video Analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillén, F.; Jiménez, H. Characteristics Desirable in Arbitration and the Judgment Sports. Mag. Psychol. Sport 2001, 10, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Diotaiuti, P.; Falese, L.; Mancone, S.; Purromuto, F. A Structural Model of Self-Efficacy in Handball Referees. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Santos, D.; Pino-Ortega, J.; García-Rubio, J.; Cowgirl, T.O.; Ibáñez, S.J. Internal and External Demands in Basketball Referees during the U-16 European Women’s Championship. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Santos, D.; Gómez-Ruano, M.A.; Cowgirl, A.; Ibáñez, S.J. Systematic Review of Basketball Referees’ Performances. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2020, 20, 495–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, F.; Feltz, D. A Conceptual Model of Referee Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaenes, C.C.; Bohórquez, M.R.; Caracuel, J.C.; López, A.M. Emotional State and Stress Situations in Basketball Referees. J. Sport Psychol. 2012, 12, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, B.T.; Ommundsen, Y.; Haugen, T. Referee Efficacy in the Context of Norwegian Soccer Referees—A Meaningful Construct. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 38, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Loaiza, H.; Holguín, J.; Arenas, J.; Núñez, C.; Barbosa-Granados, S.; García-Mas, A. Psychological Characteristics of Sports Performance: Analysis of Professional and Semi-Professional Football Referees. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2020, 20, 1861–1868. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.; Serrat, S.; Castillo, E.; Nuviala, A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Validity of the Sexual Harassment Scale in Football Refereeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Santos, D.; Ibáñez, S.J. Design and Validation of a Instrument of Observation for the Evaluation of a Basketball Referee (IOVAB). SPORT TK-Euro-Am. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 5, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Barbero, Y.; Vila, E.; Maciá, A.; Pérez-Llantada, C.; Navas, M.J. Spanish Adaptation of Leon Mann’s DMQ-II Questionnaire. J. Gen. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 46, 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno, F.; Buceta, J.M.; Lahoz, D.; Sanz, G. Evaluation of the Decision-Making Process in the Context of Sports Refereeing: Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Adaptation of the DMQ II Questionnaire in Handball Referees. J. Sport Psychol. 1998, 7, 249–258. [Google Scholar]

- Sabag, E.; Lidor, R.; Arnon, M.; Morgulev, E.; Bar-Eli, M. Teamwork and Decision Making among Basketball Referees: The 3PO Principle, Refereeing Level, and Experience. J. Hum. Kinet. 2023, 89, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, L.; Burnett, P.; Radford, M.; Ford, S. The Melbourne Decision Making Questionnaire: An Instrument for Measuring Patterns for Coping with Decisional Conflict. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 1997, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. In Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Santos, D.; Gamonales, J.M.; León, K.; Muñoz, J. A Case Study: Characterization of Physiological, Kinematic and Neuromuscular Demands of Handball Referee during Competition. E-Handball Mag. Sci. Sport 2017, 13, 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Aguilar, J.; Castillo-Rodriguez, T.O.; Chinchilla-Minguet, J.L.; Onetti-Onetti, W. Relationship between Age, Category and Experience with the Soccer Referee’s Self-Efficacy. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaissidis-Rodafinos, A.; Anshel, M.H. Sources of and Responses to Acute Stress in Adults and Adolescent Australian Basketball Referees. Aust. J. Sci. Med. Sport 1993, 25, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Castagna, C.; Abt, G.; D’Ottavio, S.; Weston, M. Age-Related Effects on Fitness Performance in Elite-Level Soccer Referees. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nurcahya, Y.; Kusumah, W.; Mulyana, D.; Kodrat, H. Analysis of Football Referee Satisfaction in Making Decision Based on Experience Levels. J. Pendidik. Jasm. Dan Olahraga 2021, 6, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMahon, C.; Starkes, J.; Deakin, J. Referee Decision Making in a Video-Based Infringement Detection Task: Application and Training Considerations. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2007, 2, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Men | 27.0 | 6.2 |

| Women | 24.5 | 3.3 | |

| Total experience as a referee | Men | 7.7 | 4.8 |

| Women | 5.85 | 2.0 | |

| Total experience in senior categories | Men | 5.9 | 5.1 |

| Women | 4.2 | 2.1 |

| Age | Factor 1. Stress in Decision-Making | Factor 2. Positive Quick Decision with Uncertainty | Factor 2. Negative Quick Decision with Uncertainty | Factor 3. Determination and Commitment in Decision Making | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Post Hoc Comparison | p-Value | ES | M | SD | Post Hoc Comparison | p-Value | ES | M | SD | Post Hoc Comparison | p-Value | ES | M | SD | Post Hoc Comparison | p-Value | ES | |

| 18–24 (n = 25) | 135 | 0.43 | vs. 25–30 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.42 | vs. 25–30 | 0.26 | −0.23 | 2.97 | 0.51 | vs. 25–30 | 1.00 | −0.02 | 2.19 | 0.30 | vs. 25–30 | 1.00 | 0.01 |

| 25–30 (n = 20) | 133 | 0.33 | vs. >30 | 0.03 | 0.92 | 1.25 | 0.56 | vs. >30 | 0.52 | 0.15 | 2.93 | 0.71 | vs. >30 | 0.33 | −0.21 | 2.18 | 0.29 | vs. >30 | 0.27 | −0.18 |

| >30 (n = 13) | 0.99 | 0.41 | vs. 18–24 | 0.05 | 0.87 | 1.03 | 0.54 | vs. 18–24 | 0.74 | −0.04 | 3.31 | 0.46 | vs. 18–24 | 0.22 | −0.24 | 2.29 | 0.34 | vs. 18–24 | 0.37 | −0.18 |

| Year of experience in senior categories | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0–3 (n = 26) | 1.28 | 0.41 | vs. 4–8 | 0.82 | −0.18 | 1.18 | 0.46 | vs. 4–8 | 0.68 | 0.16 | 2.86 | 0.63 | vs. 4–8 | 0.24 | −0.23 | 2.17 | 0.32 | vs. 3–8 | 1.00 | −0.10 |

| 4–8 (n = 21) | 1.35 | 0.44 | vs. >8 | 0.36 | 0.50 | 0.98 | 0.54 | vs. >8 | 1.00 | 0.16 | 3.11 | 0.52 | vs. >8 | 1.00 | −0.09 | 2.25 | 0.26 | vs. >8 | 1.00 | −0.03 |

| >8 (n = 11) | 1.08 | 0.33 | vs. 0–3 | 0.18 | 0.67 | 1.09 | 0.52 | vs. 0–3 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 3.30 | 0.51 | vs. 0–3 | 0.10 | −0.28 | 2.24 | 0.37 | vs. 0–3 | 1.00 | −0.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nieto-Acevedo, R.; García-Sánchez, C.; Marquina Nieto, M.; Mon-Lopez, D.; Hortiguela-Herradas, A.; Lorenzo-Calvo, J. Analysis of Basketball Referee Decision-Making Using the DMQ-II Questionnaire. Sports 2025, 13, 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13080270

Nieto-Acevedo R, García-Sánchez C, Marquina Nieto M, Mon-Lopez D, Hortiguela-Herradas A, Lorenzo-Calvo J. Analysis of Basketball Referee Decision-Making Using the DMQ-II Questionnaire. Sports. 2025; 13(8):270. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13080270

Chicago/Turabian StyleNieto-Acevedo, Raúl, Carlos García-Sánchez, Moisés Marquina Nieto, Daniel Mon-Lopez, Andrea Hortiguela-Herradas, and Jorge Lorenzo-Calvo. 2025. "Analysis of Basketball Referee Decision-Making Using the DMQ-II Questionnaire" Sports 13, no. 8: 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13080270

APA StyleNieto-Acevedo, R., García-Sánchez, C., Marquina Nieto, M., Mon-Lopez, D., Hortiguela-Herradas, A., & Lorenzo-Calvo, J. (2025). Analysis of Basketball Referee Decision-Making Using the DMQ-II Questionnaire. Sports, 13(8), 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13080270