1. Introduction

Fundamental movement skills (FMS) are associated with improved health-related quality of life in children [

1]. This competency (measured through muscular strength, muscular endurance, and mobility) is an essential health indicator of school-age children. The literature supports that FMS is best taught during middle school ages as seen in the hourglass model [

2]. This model describes how children’s physical activity begins broadly with free play, narrows during early childhood as they develop FMS, and then broadens again as those skills enable participation in a wide range of lifelong physical activities. Likewise, competency in fundamental movements is associated with physical activity levels in childhood and throughout their lifespan [

1]. Research supports that rural children tend to have lower performance scores for FMS when compared to their urban counterparts [

3]. The observed data discrepancy is not a result of an inability to perform but rather stems from disparities in resources and experiences [

4]. Thus, there is a need to improve access to fundamental movement-based physical activity opportunities in rural communities, specifically for children, to promote lifelong health.

Leading organizations in childhood physical activity emphasize the importance of developing FMS during childhood to promote lifelong health and confidence in being active. Project Play, an initiative by the Aspen Institute [

5], focuses on increasing youth sports participation through accessible, high-quality programs, offering strategies for creating successful initiatives that support children’s physical activity. These strategies include 8 “plays” (i.e., a framework): (1) ask kids what they want, (2) reintroduce free play, (3) encourage sport sampling, (4) revitalize in-town leagues, (5) think small, (6) design for development, (7) train all coaches, and (8) emphasize prevention. In this study, the intervention, Hoosier Strength, was designed with these “plays” in mind. First, the program is an extension of a published human-centered participatory co-design (a collaborative design approach that actively involves stakeholders in the design process) with children from the target community [

6], as well as a multi-level physical activity needs assessment including children [

7] (Play 1). Hoosier Strength was also designed to incorporate elements of free play, such as allowing participants to design obstacle courses and challenges while still incorporating new skills (Play 2). Also, the program is an extension of Hoosier Sport, a sport-based youth-development program aiming to expose rural children to a range of sports (Play 3). Moreover, Hoosier Strength was created with development in mind, focusing on foundational FMS such as squats (Play 6). Lastly, the program uses a pilot tested college student-focused implementation strategy [

8,

9], where college students complete a training course before implementation (Play 7). While none of these characteristics are entirely innovative on their own, since many types of physical activity interventions have been conducted, the combination of them, alignment with Project Play, and emphasis on physical health outcomes creates a relatively novel approach.

Research in physical education (PE) has used self-determination theory [

10] to explain motivation to engage in activity. According to self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs mini-theory, autonomous motivation increases when three fundamental psychological needs are fulfilled: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Autonomy pertains to one’s sense of control during activities. Competence involves perceiving one’s capability to complete tasks effectively. Relatedness encompasses feeling accepted and connected to others. Previous research has indicated that satisfying these basic psychological needs during PE classes correlates with adolescents’ motivation in PE programs [

10,

11]. Indeed, relatedness among peers and instructors is a predictor for participation in PE, and low feelings of relatedness may result in poor FMS outcomes [

11]. Understanding and addressing these fundamental psychological needs within PE not only fosters motivation but also significantly impacts the development of FMS and overall engagement among adolescents.

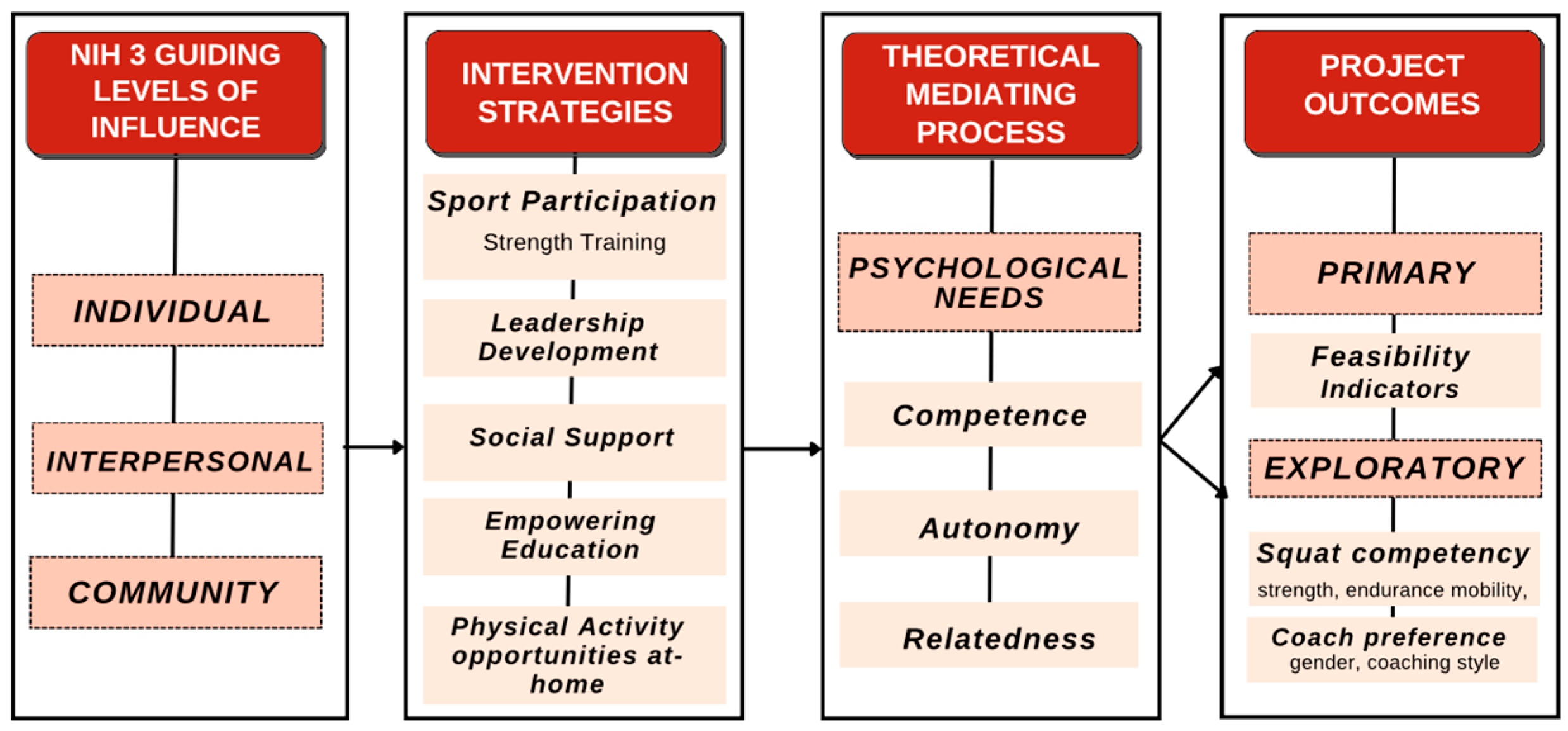

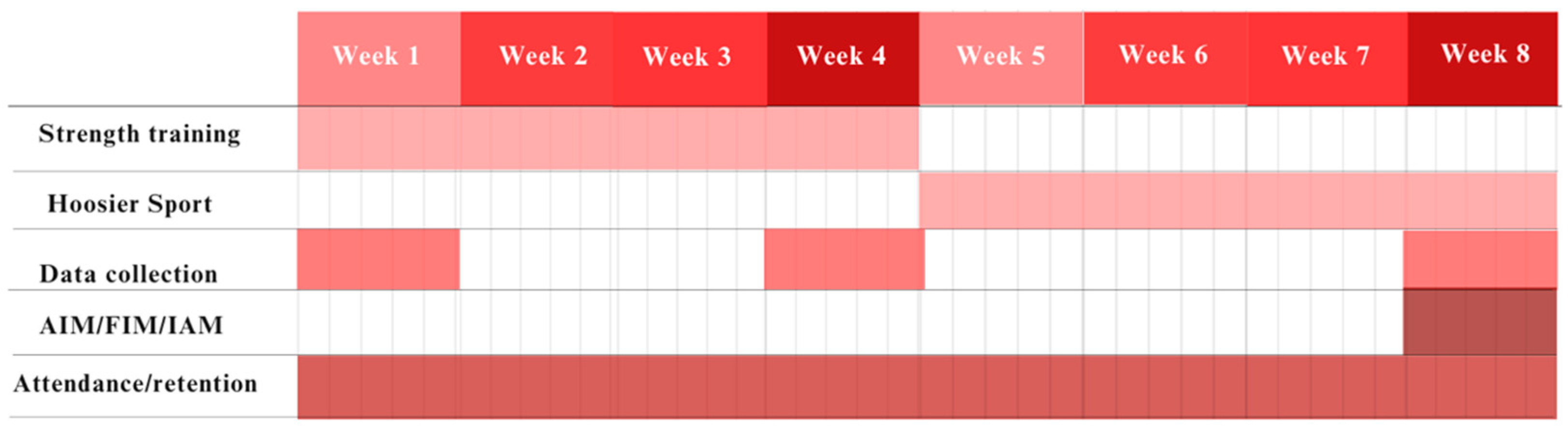

The present study conducted a four-week, non-randomized controlled feasibility study involving 8 training sessions, with data collection occurring pre-intervention, post-intervention, and a follow-up time point. The study aimed to enhance FMS, specifically focusing on the squat exercise, in 6th and 7th grade children at a rural middle school. The intervention consisted of a progressive squat program implemented by college students within a middle school PE curriculum, gradually increasing exercise difficulty from unloaded to loaded with various axial loadings (e.g., goblet squat, front squat, back squat). The focus of this study was not on resistance training outcomes specifically, but rather feasibility indicators for implementing FMS curriculums into an under-resourced rural middle school. The primary objective was to test the feasibility of Hoosier Strength in a rural middle school sample, and the secondary objective was to observe the preliminary changes in FMS-related outcomes pre- to post-intervention and at follow-up for maintenance. Our primary hypothesis was that the Hoosier Strength intervention would be feasible as defined by “good” scores (median greater than a score of 16) for multiple trial-related (e.g., recruitment capability and retention) and intervention-related feasibility indicators (e.g., Acceptability of Intervention Measures [AIM], Intervention Appropriateness Measure [IAM], and Feasibility of Intervention Measure [FIM]). Our secondary hypothesis was that at the end of our 4-week intervention, the participants would have an increase in FMS outcomes (e.g., range of motion, muscular endurance, load lifted). Our exploratory objective was to explore how participants responded to different coaches on the Hoosier Strength coaching team (i.e., gender, coaching style during activities). This exploratory objective acknowledges the potential impact of coach-participant dynamics on both the feasibility of the intervention and the effectiveness of FMS development. By examining these interactions, we aim to better understand how coach characteristics and behaviors may influence children’s engagement, motivation, and skill acquisition in the context of a rural PE setting.

4. Discussion

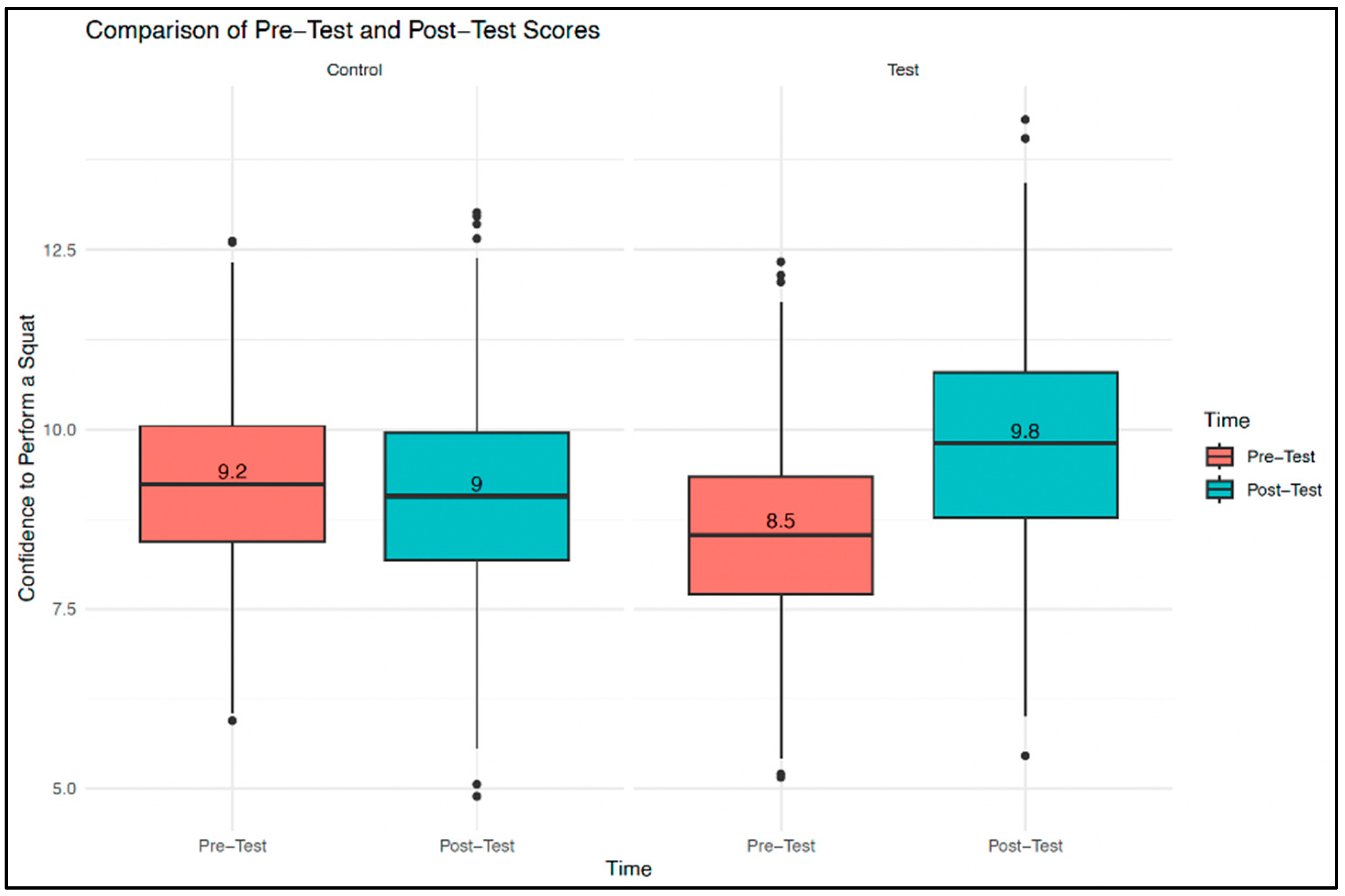

The present study had three objectives: to test the feasibility of Hoosier Strength; to identify potential changes in squat performance (e.g., range of motion and muscular endurance) and psychological outcomes (e.g., fulfillment of basic psychological needs, confidence to squat); and to explore the coaching preferences of middle school students. The study yielded four key findings: (1) the trial- and intervention-related feasibility indicators were consistently high throughout the 4-week intervention and at follow-up, indicating that the Hoosier Strength program is feasible to implement; (2) there were no significant changes in squat performance outcomes over the 4-week intervention; (3) participants’ confidence in their ability to squat at the end of the intervention was significantly predicted by their squat knowledge at baseline; and (4) participants prioritized leadership and team management over tactical analysis, indicating a preference for coaches who foster teamwork. These findings offer a transparent approach for evaluating the feasibility and preliminary outcomes of the Hoosier Strength intervention, thereby encouraging further investigation into strength training interventions in rural schools.

For our first key finding, Hoosier Strength was found to have good feasibility for the targeted population (

Table 2). This was an important measurement based on pre-existing literature. For example, similar research has found that feasibility scores (AIM, FIM, IAM) pre-intervention correlated with the success of an intervention focused on youth physical activity levels [

17]. Additionally, our utilization of FIM, IAM, and AIM scales is supported by other studies as a validated method [

15,

18]. Both AIM and IAM assess aspects of intervention readiness; however, AIM focuses on acceptability, measuring stakeholders’ attitudes and reactions toward the intervention, while IAM focuses on appropriateness, evaluating the fit and relevance of the intervention to the specific context or setting. Likewise, FIM assesses the feasibility of implementing the intervention within a specific context or setting, such as resource availability, organizational support, and logistical constraints. Our previous pilot work has found that Hoosier Sport programs report high feasibility, acceptability, and appropriateness as reported by the children [

6]. This pilot study specifically found that intervention-related scores (FIM, AIM, and IAM) consistently surpassed the “good” threshold, and the program had a 100% retention and recruitment success.

Furthermore, children’s opinions are rarely incorporated into the research process [

19]. An important component of Hoosier Strength, in line with Project Play’s Play 1 (i.e., ask kids what they want), is assessing the participants’ opinions of the intervention. This is achieved specifically in week 4 of the intervention by utilizing the feasibility scales (FIM, IAM, AIM) in a survey taken by the participants (middle school-aged children). This allows for Hoosier Strength to evolve with the wants and needs of the children in mind. Overall, participants reported a positive perception of the intervention. The data showed high scores for accessibility, appropriateness, and feasibility (scored above the median of 16), indicating positive participant perception of Hoosier Strength (

Table 1). For future applications, studies should consider utilizing these feasibility indicators, specifically targeted at youth participants.

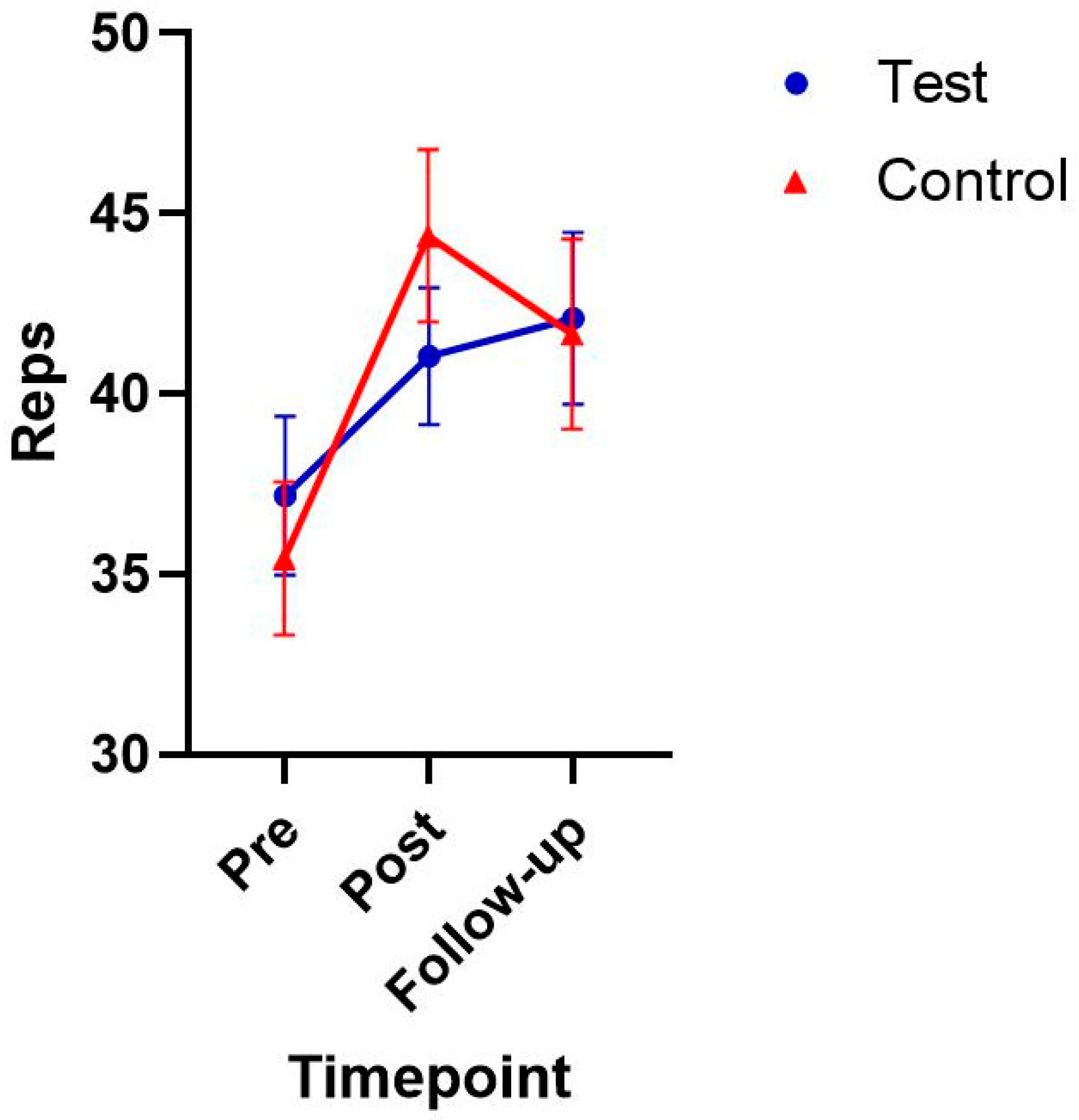

Second, physiological performance changes were not identified following Hoosier Strength. Squat ROM and muscular endurance showed no significant difference pre- and post-intervention, implying limited statistical impact on this aspect of squat performance (see limitations section for environmental factors). Although non-significant, post-intervention muscular endurance gains (Control: +25%, Test: +10%) suggest there may be clinical relevance for future longer-duration trials. Other research has found that school-based strength interventions can increase resistance training-related repetitions [

20] and ROM [

21]. One potential reason for our non-significant results is that focusing on squat technique with lower repetitions, rather than higher repetitions/volume, may have influenced the outcomes. Furthermore, four-week interventions may be insufficient for neuromuscular adaptations; 8–12 weeks are typical for significant FMS gains [

22]. Our low-volume programming prioritized technique over load, potentially limiting endurance gains vs. higher-repetition protocols [

23]. Research suggests that training with higher reps under load can improve muscular endurance in youths [

20]. The decision to use this lower-volume approach in our intervention was based on a focus on physical literacy and working within the confines of an existing program. Additionally, the non-significant changes in squat ROM could also be due to lack of duration and frequency of the intervention. Other research has shown that resistance training can improve ROM, though no optimal duration has been established [

21]. Future studies should investigate the ideal duration and frequency of resistance training to enhance ROM. Additionally, our sample participated in Hoosier Sport, a physical activity program focused on sports other than strength training (see

Section 5: Limitations), which may have elevated their baseline ROM compared to untrained adolescents. This may have limited the amount of change observed. Nonetheless, improving ROM remains essential for enhancing physical literacy. For example, research has found that range of motion supports FMS (e.g., running, jumping, squatting) through more efficient and effective movement patterns [

22]. This aligns with Project Play’s Play 6 (i.e., design for development). Our future goal is to continue to expand on this program to allow for development across all components of FMS competency.

The third finding concerns how baseline knowledge might predict psychological outcomes, specifically confidence in squatting, post-intervention. This finding revealed that participants’ knowledge of the squat movement at the start of the intervention significantly predicted their confidence in performing squats at the end. This suggests that enhancing initial knowledge of exercises could be a valuable strategy for boosting confidence and improving overall performance in strength training programs. A recent scoping review supports the overall concept of physical literacy/knowledge promoting performance and self-efficacy but results remain heterogeneous and more research is needed [

24]. Indeed, some programs may benefit from initially increasing knowledge of movements or exercise (i.e., physical literacy) before progressing to teaching specific skills and movements. This approach is supported by other research suggesting that promoting physical literacy can aid in the development of fundamental movement skills [

25]. Additionally, research supports that an increase in autonomy in exercise or in terms of motivation is predictive of exercise participation and the extent to which one will participate [

26]. Based on our findings and current literature, we believe that future research should focus on establishing a strong baseline knowledge of physical literacy before implementing physical practice, as this could enhance intervention outcomes.

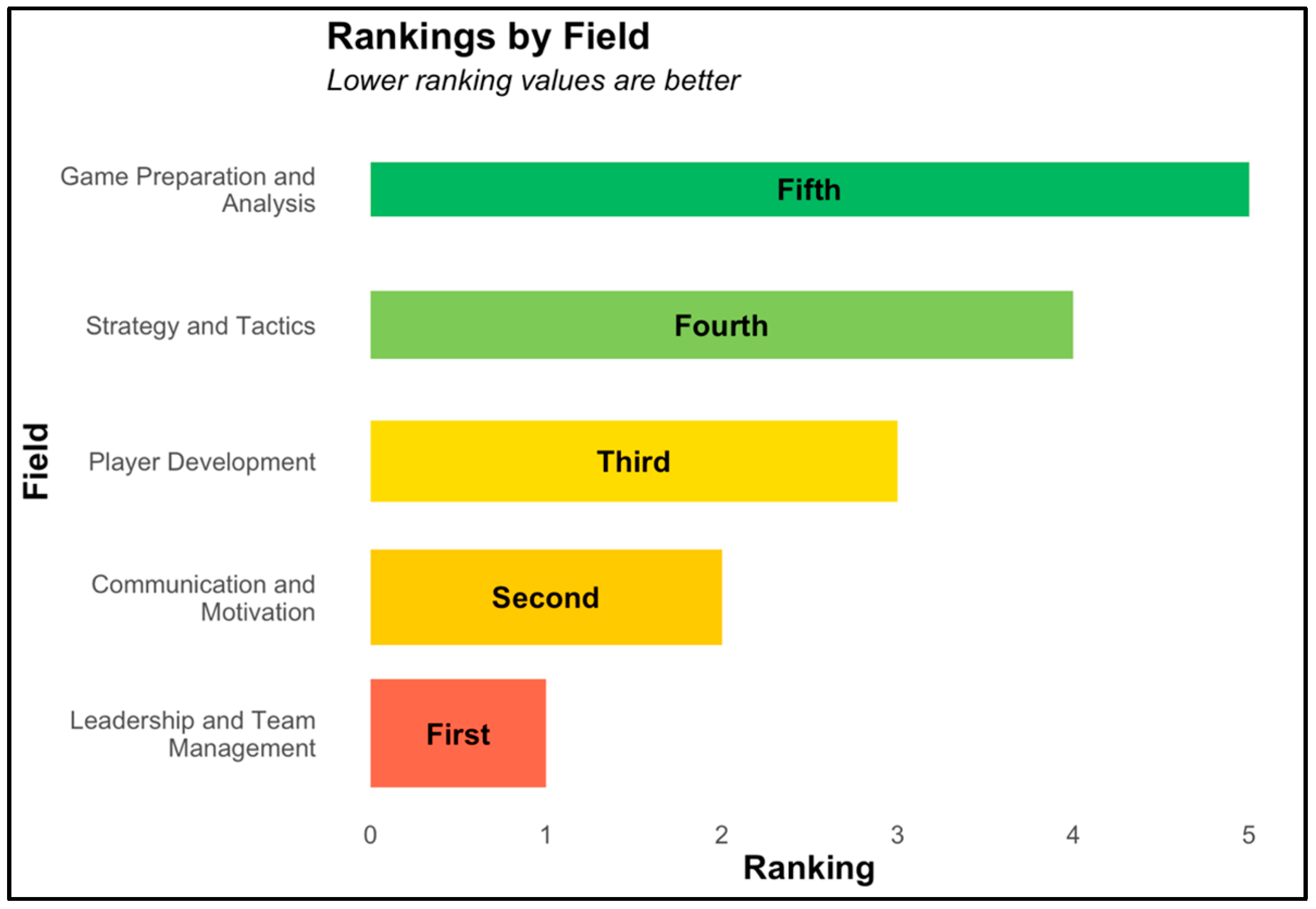

Finally, we explored the coaching preferences of middle school students. Based on survey questions, we assessed certain preferences the students had for various coaching traits. A significant number of participants expressed no preference for having either a male or a female coach in Hoosier Strength, but the past experiences of the participants showed preferences for the gender of coaches (e.g., which gender they preferred as a coach in experiences outside of Hoosier Strength, with 50% preferring male coaches). Other research substantiates our findings of no preference for a coach’s gender [

27]. However, empirical work exploring gender preferences in coaching has found that youth sports are typically dominated by male coaches, which could hinder a safe, positive, and developmentally supportive sports experience based on characteristics male coaches tend to possess [

28]. Combined, these studies highlight the importance of diverse coaching options. Also, the participants reported leadership and team management as the most important coaching value, while game preparation and analysis ranked lowest. This suggests that the targeted population prefers an environment that fosters teamwork rather than skill work alone. Team-focused approaches may be a valuable strategy for designing future interventions in rural contexts. Also, in line with Project Play’s Play 7

(Train all coaches)

, all coaches of Hoosier Strength underwent training before leading the participants through the program. This effort to ensure competent coaches was reflected by the findings that there was not one coach who was preferred over another. These findings support the use of college-aged students to coach/implement FMS-related interventions in youth populations.

In conclusion, Hoosier Strength demonstrated high feasibility in a rural school. While physiological outcomes were statistically unchanged post-intervention, baseline knowledge predicted confidence gains. Future studies should extend the duration, increase sample sizes, and prioritize coaching strategies that foster teamwork.

5. Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the sample size was not randomized, which affects the ability to interpret causal relationships. This lack of randomization was justified based on the feasibility of working within the school’s existing class structure. We plan to add randomization to future larger-scale study designs with multiple schools. Second, the sample size was relatively small, with only 36 participants. The control group consisted of 12 participants, while the test group had 24 participants. The smaller size of the control group led to greater variability in their data, complicating the comparison between the test and control groups. However, a strength of this study was the pragmatic design, which focused on practical and applicable outcomes, increasing the likelihood that the findings are relevant to real-world settings. Third, the control group had prior exposure to physical activity education and training through Hoosier Sport, another intervention program aimed at promoting physical activity. This prior experience could have enhanced their performance on the FMS competency tests, potentially biasing the results. Also, the strength assessment was limited by the maximum load used in the study. The heaviest weight was a 30-pound dowel bar, which all participants could successfully squat to a box at parallel. To accurately measure changes in muscular strength over the intervention period, a broader range of weights is necessary. Also, during the squat endurance test, students squatted to a box set at a height parallel to their knees. This provided an external cue for squat depth, which may have allowed students of varying ability levels to perform high repetitions. A loaded squat could have better distinguished students with higher FMS competency by requiring more muscle recruitment and making depth more challenging compared to an unloaded squat. Additionally, future studies should consider increasing the duration of the intervention to allow sufficient time for physiological changes to occur. Lastly, while our data showed that both satisfaction and frustration scores declined, this outcome was unexpected, as these two variables typically work in opposition to one another. The lack of statistical significance in both outcomes may suggest that the intervention’s effects were too subtle to be detected by the BPNSFS within the study’s timeframe or sample size. This implies that while the intervention may have had some influence, its impact on psychological need satisfaction and frustration might not have been strong enough to produce measurable changes within the study’s design.