Accelerating an Olympic Decathlete’s Return to Competition Using High-Frequency Blood Flow Restriction Training: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Presentation

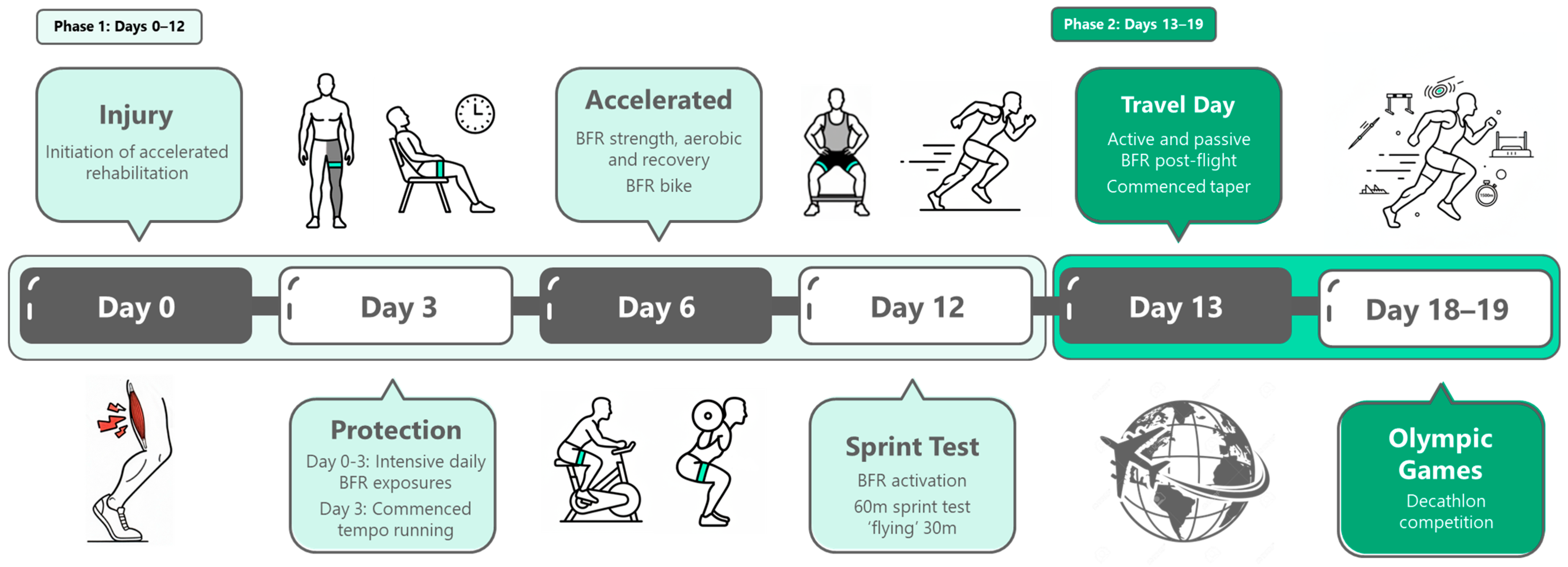

2.2. Rehabilitation Framework

2.3. Rehabilitation Program Overview

3. Results

3.1. Running Progression

3.2. Return to Competition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Edouard, P.; Pollock, N.; Guex, K.; Kelly, S.; Prince, C.; Navarro, L.; Branco, P.; Depiesse, F.; Gremeaux, V.; Hollander, K. Hamstring muscle injuries and hamstring specific training in elite athletics (track and field) athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 10992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudisill, S.S.; Varady, N.H.; Kucharik, M.P.; Eberlin, C.T.; Martin, S.D. Evidence-based hamstring injury prevention and risk factor management: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Sports Med. 2023, 51, 1927–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, B.; McAleer, S.; Kelly, S.; Chakraverty, R.; Johnston, M.; Pollock, N. Hamstring rehabilitation in elite track and field athletes: Applying the British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification in clinical practice. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 1464–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, N.; James, S.L.J.; Lee, J.C.; Chakraverty, R. British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification: A new grading system. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 1347–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poursalehian, M.; Lotfi, M.; Zafarmandi, S.; Bahri, R.A.; Halabchi, F. Hamstring injury treatments and management in athletes: A systematic review of the current literature. JBJS Rev. 2023, 11, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.R.; Loenneke, J.P.; Slattery, K.M.; Dascombe, B.J. Blood flow restricted exercise for athletes: A review of available evidence. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loenneke, J.P.; Wilson, G.J.; Wilson, J.M. A mechanistic approach to blood flow occlusion. Int. J. Sports Med. 2010, 31, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.D.; Hughes, L.; Warmington, S.; Burr, J.; Scott, B.R.; Owens, J.; Abe, T.; Nielsen, J.L.; Libardi, C.A.; Laurentino, G.; et al. Blood flow restriction exercise position stand: Considerations of methodology, application, and safety. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 533. [Google Scholar]

- Loenneke, J.P.; Allen, K.M.; Mouser, J.G.; Thiebaud, R.S.; Kim, D.; Abe, T.; Bemben, M.G. Blood flow restriction in the upper and lower limbs is predicted by limb circumference and systolic blood pressure. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 115, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, P.S.; Willoughby, D.S. Mechanisms behind blood flow-restricted training and its effect toward muscle growth. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2019, 33, S167–S179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, H.; Morita, T.; Iida, H.; Asada, K.; Kato, M.; Uno, K.; Hirose, K.; Matsumoto, A.; Takenaka, K.; Hirata, Y. Hemodynamic and hormonal responses to a short-term low-intensity resistance exercise with the reduction of muscle blood flow. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 95, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopinatth, V.; Garcia, J.R.; Reid, I.K.; Knapik, D.M.; Verma, N.N.; Chahla, J. Blood flow restriction enhances recovery after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2025, 41, 1048–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, W.-S.; Kim, S.-H.; Nam, S.-S.; Kim, J.-W.; Moon, H.-W. Effects of rehabilitation exercise with blood flow restriction after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centner, C.; Lauber, B.; Seynnes, O.R.; Jerger, S.; Sohnius, T.; Gollhofer, A.; König, D. Low-load blood flow restriction training induces similar morphological and mechanical achilles tendon adaptations compared with high-load resistance training. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 127, 1660–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öberg, S.; von Schewelov, L.; Tengman, E. The impact of blood flow restriction training on tendon adaptation and tendon rehabilitation–a scoping review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2025, 26, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, C.J.; Roberts, L.A.; Bjørnsen, T.; Peake, J.M.; Coombes, J.S.; Raastad, T. Where does blood flow restriction fit in the toolbox of athletic development? A narrative review of the proposed mechanisms and potential applications. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 2077–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffries, O.; Waldron, M.; Pattison, J.R.; Patterson, S.D. Enhanced local skeletal muscle oxidative capacity and microvascular blood flow following 7-day ischemic preconditioning in healthy humans. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriel, R.A.; de Souza, H.L.R.; da Mota, G.R.; Marocolo, M. Declines in exercise performance are prevented 24 hours after post-exercise ischemic conditioning in amateur cyclists. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slysz, J.T.; Burr, J.F. Ischemic preconditioning: Modulating pain sensitivity and exercise performance. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 696488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.D.; Bezodis, N.E.; Glaister, M.; Pattison, J.R. The effect of ischemic preconditioning on repeated sprint cycling performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 1652–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, B.; Taşkın, H.B.; Šimenko, J. Effect of ischemic preconditioning on acute recovery in elite judo athletes: A randomized, single-blind, crossover trial. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2023, 18, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaven, C.M.; Cook, C.J.; Kilduff, L.; Drawer, S.; Gill, N. Intermittent lower-limb occlusion enhances recovery after strenuous exercise. APNM 2012, 37, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edouard, P.; Kerspern, A.; Pruvost, J.; Morin, J.B. Four-year injury survey in heptathlon and decathlon athletes. Sci. Sports 2012, 27, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edouard, P.; Hollander, K. Injuries by events in combined events (decathlon and heptathlon) during 11 international outdoor athletics championships. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2025, 35, e70142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognetti, D.J.; Sheean, A.J.; Owens, J.G. Blood flow restriction therapy and its use for rehabilitation and return to sport: Physiology, application, and guidelines for implementation. Arthrosc. Sports Med. Rehabil. 2022, 4, e71–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, R.A.; Mitchell, E.A.; Taylor, C.W.; Bishop, D.J.; Christiansen, D. Blood-flow-restricted exercise: Strategies for enhancing muscle adaptation and performance in the endurance-trained athlete. Exp. Physiol. 2021, 106, 837–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.E.; De Freitas, M.C.; Zanchi, N.E.; Lira, F.S.; Cholewa, J.M. The role of inflammation and immune cells in blood flow restriction training adaptation: A review. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, E.N.; Elshaar, R.; Mohr, K.; Watanabe, D.; Jue, G.; Milligan, H.; Brown, P.; Limpisvasti, O. The effects of blood flow restriction training on upper and lower extremity strengthening. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2019, 35, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loenneke, J.P.; Fahs, C.A.; Rossow, L.M.; Sherk, V.D.; Thiebaud, R.S.; Abe, T.; Bemben, D.A.; Bemben, M.G. Effects of cuff width on arterial occlusion: Implications for blood flow restricted exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 2903–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Łysoń-Uklańska, B.; Błażkiewicz, M.; Kwacz, M.; Wit, A. Muscle force patterns in lower extremity muscles for elite discus throwers, javelin throwers and shot-putters—A case study. J. Hum. Kinet. 2021, 78, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, N.; Patel, A.; Chakraverty, J.; Suokas, A.; James, S.L.J.; Chakraverty, R. Time to return to full training is delayed and recurrence rate is higher in intratendinous (‘c’) acute hamstring injury in elite track and field athletes: Clinical application of the British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, A.L.; Baeza-Raja, B.; Perdiguero, E.; Jardí, M.; Muñoz-Cánoves, P. Interleukin-6 is an essential regulator of satellite cell-mediated skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cell Metab. 2008, 7, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissanen, T.T.; Korpisalo, P.; Markkanen, J.E.; Liimatainen, T.; Ordén, M.-R.; Kholová, I.; De Goede, A.; Heikura, T.; Grȯhn, O.H.; Ylä-Herttuala, S. Blood flow remodels growing vasculature during vascular endothelial growth factor gene therapy and determines between capillary arterialization and sprouting angiogenesis. Circulation 2005, 112, 3937–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvinen, T.A.H.; Järvinen, T.L.N.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kalimo, H.; Järvinen, M. Muscle injuries: Biology and treatment. Am. J. Sports Med. 2005, 33, 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, C.S.; Piasecki, M.; Atherton, P.J. Skeletal muscle immobilisation-induced atrophy: Mechanistic insights from human studies. Clin. Sci. 2024, 138, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilroe, S.P.; Fulford, J.; Jackman, S.R.; Van Loon, L.J.C.; Wall, B.T. Temporal muscle-specific disuse atrophy during one week of leg immobilization. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.M.; Godwin, J.S.; Plotkin, D.L.; McIntosh, M.C.; Mattingly, M.L.; Agostinelli, P.J.; Mueller, B.J.; Anglin, D.A.; Berry, A.C.; Vega, M.M.; et al. Effects of leg immobilization and recovery resistance training on skeletal muscle-molecular markers in previously resistance trained versus untrained adults. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 138, 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Du, Z.; Tao, M.; Song, Y. Effects of different hamstring eccentric exercise programs on preventing lower extremity injuries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guex, K.J.; Lugrin, V.; Borloz, S.; Millet, G.P. Influence on strength and flexibility of a swing phase–specific hamstring eccentric program in sprinters’ general preparation. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, E.J.O.; Inns, T.B.; Hatt, J.; Doleman, B.; Bass, J.J.; Atherton, P.J.; Lund, J.N.; Phillips, B.E. The time course of disuse muscle atrophy of the lower limb in health and disease. JCSM 2022, 13, 2616–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.; Varley-Campbell, J.; Fulford, J.; Taylor, B.; Mileva, K.N.; Bowtell, J.L. Effect of immobilisation on neuro-muscular function in vivo in humans: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 931–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-T.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.-C.; Hwang, I.-S. Blood flow restriction modulates common drive to motor units and force precision: Implications for neuromuscular coordination. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatela, P.; Mendonca, G.V.; Veloso, A.P.; Avela, J.; Mil-Homens, P. Blood flow restriction alters motor unit behavior during resistance exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 2019, 40, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.H.; Stampley, J.E.; Granger, J.; Scott, M.C.; Allerton, T.D.; Johannsen, N.M.; Spielmann, G.; Irving, B.A. Impact of low-load resistance exercise with and without blood flow restriction on muscle strength, endurance, and oxidative capacity: A pilot study. Physiol. Rep. 2024, 12, e16041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis-Deschênes, P.; Joanisse, D.R.; Mauriège, P.; Billaut, F. Ischemic preconditioning enhances aerobic adaptations to sprint-interval training in athletes without altering systemic hypoxic signaling and immune function. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, A.; Sakuraba, K.; Sawaki, K.; Sumide, T.; Tamura, Y. Prevention of disuse muscular weakness by restriction of blood flow. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slysz, J.T.; Boston, M.; King, R.; Pignanelli, C.; Power, G.A.; Burr, J.F. Blood flow restriction combined with electrical stimu-lation attenuates thigh muscle disuse atrophy. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2021, 53, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, T.; Connell, R.; Free, J.; Gill, N.; Hebert-Losier, K.; Beaven, M. The effect of an off-feet conditioning protocol on performance and training load response to intermittent sprint training compared to an equivalent running based protocol. Int. J. Strength. Cond. 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Chi, J.; Lei, E.F.; Wang, D. Effects of blood flow restriction training on aerobic capacity, lower limb muscle strength and mass in healthy adults: A meta-analysis. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2024, 64, 1060–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommasamudram, M.T.; Morrell, M.Z.; Clarkson, M.; Nayak, K.R.; KV, R.; Russell, A.; Warmington, S. Chronic adaptations to blood flow restriction aerobic or bodyweight resistance training: A systematic review. J. Clin. Exerc. Physiol. 2024, 13, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lemos Muller, C.H.; Farinha, J.B.; Leal-Menezes, R.; Ramis, T.R. Aerobic training with blood flow restriction on muscle hypertrophy and strength: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.; Lee, S. The effects of blood flow restriction aerobic exercise on body composition, muscle strength, blood biomarkers, and cardiovascular function: A narrative review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Singh, H.; Loenneke, J.P.; Thiebaud, R.S.; Fahs, C.A.; Rossow, L.M.; Young, K.; Seo, D.; Bemben, D.A.; Bemben, M.G. Comparative effects of vigorous-intensity and low-intensity blood flow restricted cycle training and detraining on muscle mass, strength, and aerobic capacity. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.D.W.; Girard, O.; Scott, B.R.; Peiffer, J.J. Blood flow restriction during self-paced aerobic intervals reduces mechanical and cardiovascular demands without modifying neuromuscular fatigue. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2023, 23, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceicao, M.S.; Junior, E.M.M.; Telles, G.D.; Libardi, C.A.; Castro, A.; Andrade, A.L.L.; Brum, P.C.; Urias, Ú.; Kurauti, M.A.; Júnior, J.M.C. Augmented anabolic responses after 8-wk cycling with blood flow restriction. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, H.; Slattery, F. Effects of blood flow restriction training on aerobic capacity and performance: A systematic review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.F.M.D.; Caputo, F.; Corvino, R.B.; Denadai, B.S. Short-term low-intensity blood flow restricted interval training improves both aerobic fitness and muscle strength. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Effects of aerobic training with blood flow restriction on aerobic capacity, muscle strength, and hypertrophy in young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 2025, 15, 1506386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, T.J.; Herbert, R.D.; Munn, J.; Lee, M.; Gandevia, S.C. Contralateral effects of unilateral strength training: Evidence and possible mechanisms. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 101, 1514–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendy, A.M.; Lamon, S. The cross-education phenomenon: Brain and beyond. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, E.N.; Elshaar, R.; Milligan, H.; Jue, G.; Mohr, K.; Brown, P.; Watanabe, D.M.; Limpisvasti, O. Proximal, distal, and contralateral effects of blood flow restriction training on the lower extremities: A randomized controlled trial. Sports Health 2019, 11, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilaça-Alves, J.; Magalhães, P.S.; Rosa, C.V.; Reis, V.M.; Garrido, N.D.; Payan-Carreira, R.; Neto, G.R.; Costa, P.B. Acute hormonal responses to multi-joint resistance exercises with blood flow restriction. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2022, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dankel, S.J.; Jessee, M.B.; Abe, T.; Loenneke, J.P. The effects of blood flow restriction on upper-body musculature located distal and proximal to applied pressure. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Modality | Description |

|---|---|

| Activation | Low-intensity lower-body preparatory exercises for subsequent sessions. |

| Upper-body BFR | Early-stage, band-resisted upper-body exercises wearing BFR cuffs used to generate systemic adaptive signalling while avoiding applying a mechanical load on the injured limb during the period of initial restricted lower-body training. Progressed to loaded resistance exercises later in Phase 1. |

| Right-leg strength BFR | Unilateral strength exercises for the uninjured leg conducted while the athlete was wearing BFR cuffs, serving as a high-load contralateral stimulus to maintain lower-limb strength and induce cross-education effects. |

| Lower-body strength | Higher-load compound movements (>70% 1 RM, e.g., trap bar deadlift and step-ups) reintroduced accordingly once the individual was pain-free. |

| Hamstring strengthening | Progressive isometric, eccentric, and isotonic hamstring-targeted exercises performed to restore strength and confidence. |

| Bike (stationary cycling) | Stationary cycling performed either as continuous steady-state (20 min @90RPM) or interval-based (8 × 15 s @130RPM/15 s @70RPM) cycling using a self-selected resistance setting with BFR applied to both thighs. |

| Track (running) | Running speed was self-limited by pain-free tolerance and athlete confidence. The distance was selected in consultation with the athlete according to what he felt he could achieve whilst maintaining good running mechanics. |

| Event-specific skills | Hurdles, high jump, long jump, pole vault, and throws, which were performed as modified or visualised movements to maintain technical familiarity. |

| Ischemic preconditioning | Performed in a seated position using three cycles of five minutes of inflation at 80% LOP, interspersed with three minutes of reperfusion using lower-body BFR cuffs. From Day 5, IPC was initially applied unilaterally (uninjured leg) and progressed to bilateral application. |

| Neuromuscular electro- stimulation | From Day 10, a second IPC session included low-frequency stimulation (Compex, DJO Global, Vista, CA, USA). Self-adhesive electrodes (5 × 5 cm) were positioned according to manufacturer guidelines: one electrode was placed over the distal portion of the hamstring muscle group (approximately two-thirds down the posterior thigh), and the second electrode was positioned proximally. Placement was adjusted to accommodate the position of the BFR cuff. Stimulation intensity was progressively increased until visible muscle contraction was observed without discomfort. |

| Day | Sessions | Programming | Running | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | 2 × day | UB-BFR band-resisted exercise | – | Initiation of rehabilitation; protection of injured left leg; early systemic activation using band-resisted upper-body BFR. |

| Day 2 | 3 × day | UB-BFR band-resisted exercise; R-leg STR; IPC | – | Right-leg BFR strength; left-leg glute/quad activation only; first IPC session—right-leg BFR only. |

| Day 3 | 4 × day | ACT; UB-BFR band-resisted exercise; TRACK; IPC | 5 × 30 m | First run post-injury. Introduced SL Ham Iso-Push (three foot positions) to monitor force symmetry pre-run. |

| Day 4 | 6 × day | ACT; Bike; IPC; TRACK; IPC; Ham-STR | 6 × 30 m | Bike (stationary cycling) without BFR. Left-hamstring-strength manual resistance. |

| Day 5 | 6 × day | ACT; TRACK; Bike; IPC; LB-STR; IPC | 8 × 30 m | First high-load lower-body session. IPC—BFR on both legs. |

| Day 6 | 5 × day | ACT; Bike; IPC; TRACK; IPC | 10 × 30 m | Bike (stationary cycling) BFR on both legs. |

| Day 7 | 5 × day | TRACK; Bike; IPC; LB-STR; Ham-STR; IPC | 10 × 30 m | First gym-based hamstring specific strength session. |

| Day 8 | 6 × day | ACT; TRACK; IPC; Ham-STR, Bike; IPC + NMES | 10 × 30 m | Addition of NMES to IPC in evening recovery session. |

| Day 9 | 5 × day | LB-STR; IPC; TRACK; Bike; IPC + NMES | Warm Up only | No run-specific rehab employed to allow for recovery. |

| Day 10 | 6 × day | ACT; IPC; TRACK; Ham-STR; Bike; IPC + NMES | 6 × 30 m | Increased focus running speed. |

| Day 11 | 4 × day | LB-STR; IPC; TEST; IPC + NMES | – | Reduced volume for sprint test (day 12); running technique: athlete needed to display competency in LJ and HJ with short approach efforts. |

| Day 12 | 6 × day | ACT; IPC; TRACK; Ham-STR; Bike; IPC + NMES | 60 m @95% vel | Sprint test. Passed flying 30 m and was cleared for competition. |

| Day 13 | 2 × day | TRACK; IPC + NMES | Warm Up only | Commenced taper; travel day. |

| Day 14 | 1 × day | IPC + NMES | – | Travel continued; no opportunity to train. |

| Day 15 | 4 × day | ACT; TRACK; Ham-STR; IPC + NMES | 1000 m | Event specific tapering. |

| Day 16 | 3 × day | ACT; TRACK; IPC + NMES | 5 × 60 m | Event specific tapering. |

| Day 17 | 3 × day | ACT; TRACK; IPC + NMES | Warm-up only | Final taper; mobility and activation. |

| Day 18 | 5 events | Olympic Games Competition | Competition | Day 1: 5 events completed. No performance in pole vault. |

| Day 19 | 5 events | Olympic Games Competition | Competition | Day 2: 5 events completed. Full decathlon completed without recurrence. |

| Day | Right (kg per Set) | Left (kg per Set) | Symmetry Index % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 7–8 | 32/39/39 | 25/25/25 | 64% |

| Day 10 | 32/39/39 | 32/32/32 | 82% |

| Day 12 | 32/39/39 | 32/39/39 | 100% |

| Day | Sprint Time (s) | Relative Sprint Velocity % |

|---|---|---|

| Day 6 | 13.00 | 23% |

| Day 7 | 6.08 | 50% |

| Day 8 | 3.96 | 77% |

| Day 10 | 3.28 | 93% |

| Day 12 | 2.99 | 102% |

| Event | Personal Best | Olympic Score | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 m (s) | 10.77 | 10.98 | +0.21 |

| Long Jump (m) | 7.62 | 7.36 | –0.26 |

| Shot Put (m) | 13.24 | 13.35 * | +0.11 (PB) |

| High Jump (m) | 2.11 | 2.05 | –0.06 |

| 400 m (s) | 47.84 | 49.02 | –1.18 |

| 110 mH (s) | 14.34 | 15.10 | +0.76 |

| Discus (m) | 41.70 | 43.31 * | +1.61 (PB) |

| Pole Vault (m) | 5.00 | No height | - |

| Javelin (m) | 62.48 | 58.52 | –3.96 |

| 1500 m (min:s) | 4:41 | 5:03 | +0:22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaviglio, C.; Bird, S.P. Accelerating an Olympic Decathlete’s Return to Competition Using High-Frequency Blood Flow Restriction Training: A Case Report. Sports 2025, 13, 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120436

Gaviglio C, Bird SP. Accelerating an Olympic Decathlete’s Return to Competition Using High-Frequency Blood Flow Restriction Training: A Case Report. Sports. 2025; 13(12):436. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120436

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaviglio, Chris, and Stephen P. Bird. 2025. "Accelerating an Olympic Decathlete’s Return to Competition Using High-Frequency Blood Flow Restriction Training: A Case Report" Sports 13, no. 12: 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120436

APA StyleGaviglio, C., & Bird, S. P. (2025). Accelerating an Olympic Decathlete’s Return to Competition Using High-Frequency Blood Flow Restriction Training: A Case Report. Sports, 13(12), 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports13120436