Measured vs. Estimated

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. YYET1 Assessment Protocol

2.3. Oxygen Consumption, Respiratory Exchange Ratio, Heart Rate, and Blood Lactate Accumulation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

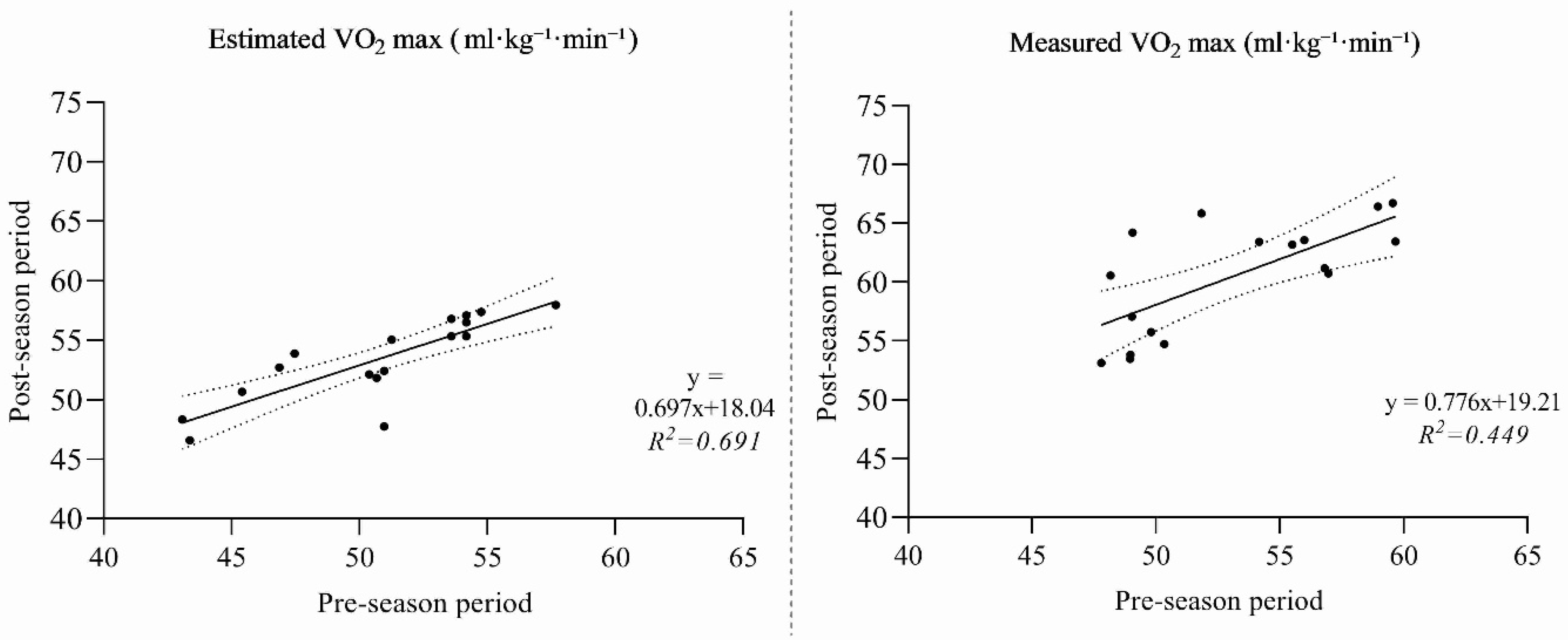

3.1. Regression Comparisons

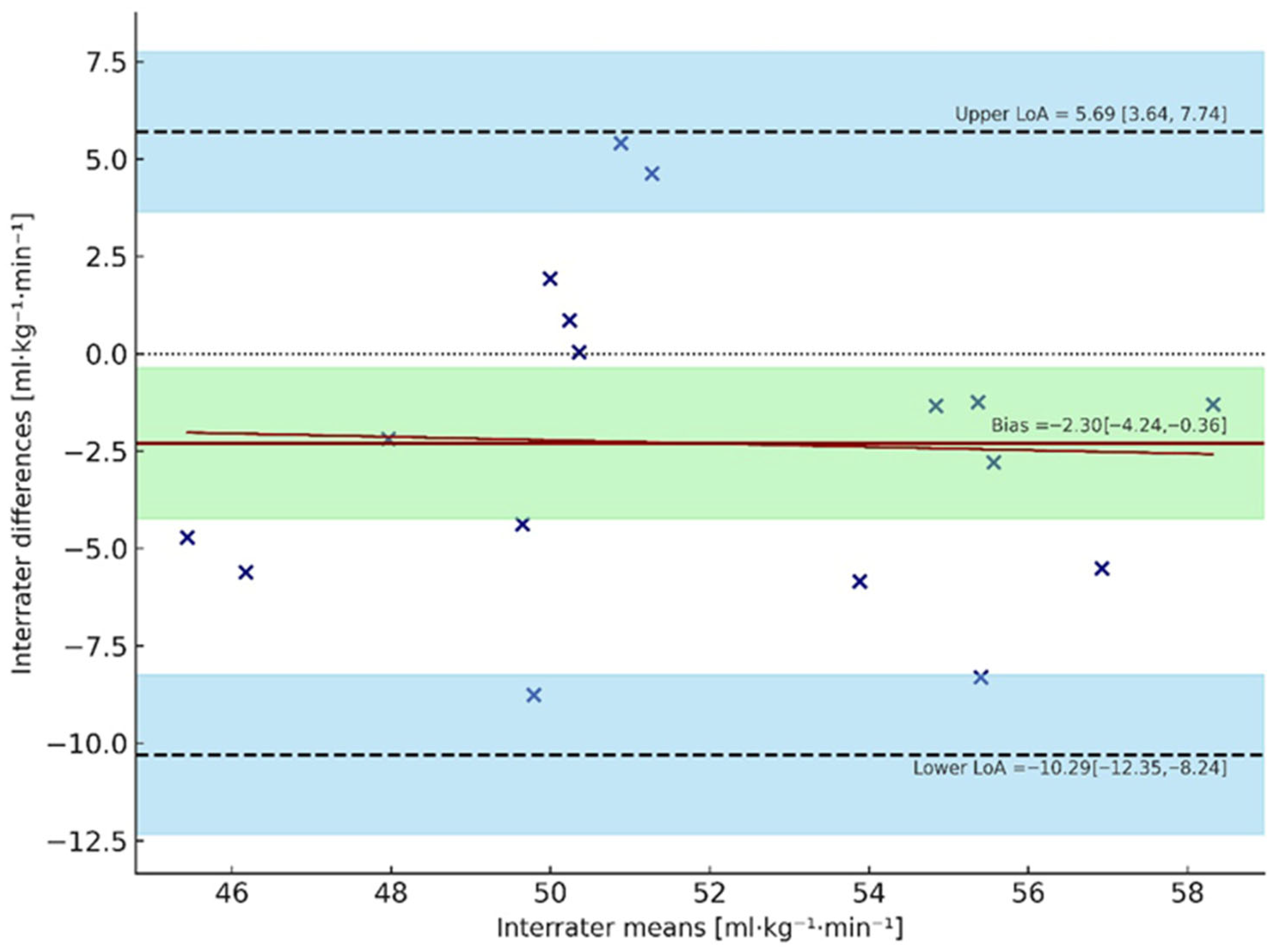

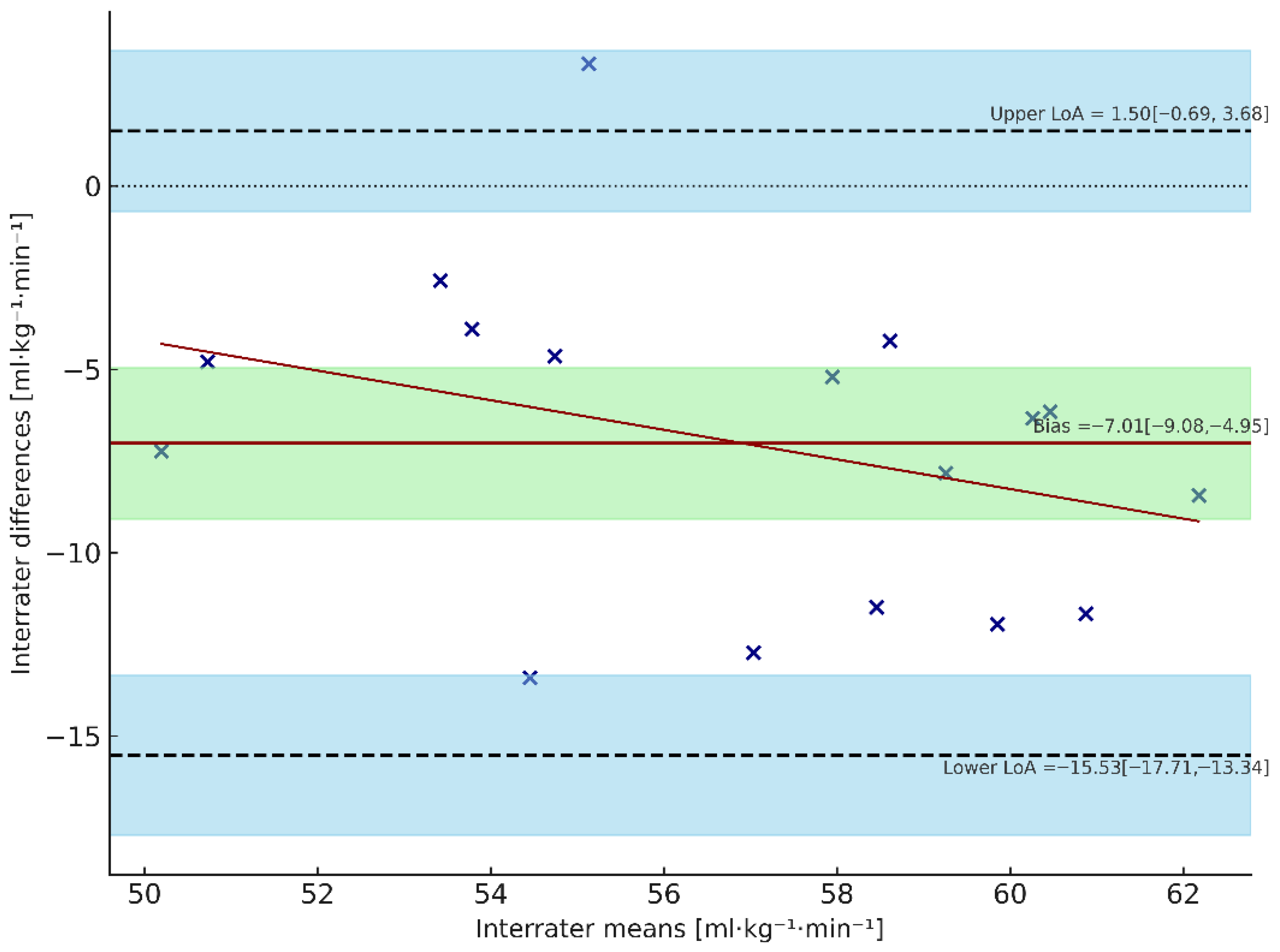

3.2. Bland–Altman Analysis

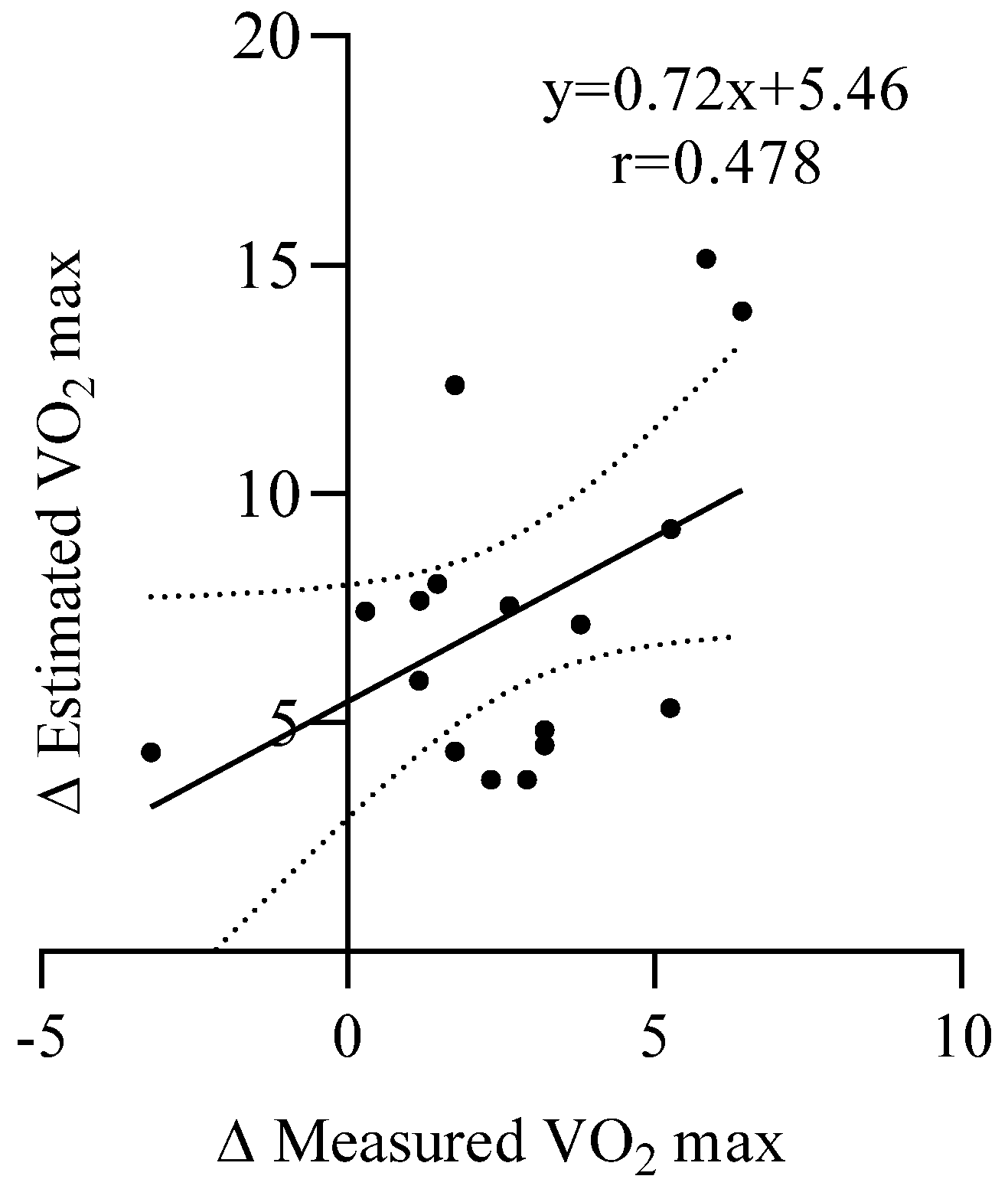

3.3. Seasonal Delta Regression

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, T.; Taberner, M.; Zhilkin, M.; Rhodes, D. Running More than before? The Evolution of Running Load Demands in the English Premier League. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2024, 19, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P.S. “Setting the Benchmark” Part 1: The Contextualised Physical Demands of Positional Roles in the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022. Biol. Sport 2024, 41, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, P.S.; Sheldon, W.; Wooster, B.; Olsen, P.; Boanas, P.; Krustrup, P. High-Intensity Running in English FA Premier League Soccer Matches. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Salvo, V.; Baron, R.; Tschan, H.; Calderon Montero, F.J.; Bachl, N.; Pigozzi, F. Performance Characteristics According to Playing Position in Elite Soccer. Int. J. Sports Med. 2007, 28, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modric, T.; Versic, S.; Stojanovic, M.; Chmura, P.; Andrzejewski, M.; Konefał, M.; Sekulic, D. Factors Affecting Match Running Performance in Elite Soccer: Analysis of UEFA Champions League Matches. Biol. Sport 2023, 40, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, G.P.; Burtscher, J.; Bourdillon, N.; Manferdelli, G.; Burtscher, M.; Sandbakk, Ø. The O2max Legacy of Hill and Lupton (1923)-100 Years On. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2023, 18, 1362–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoia, C.; Laterza, F.; Lucadamo, A.; Manzi, V.; Azzone, V.; Pullinger, S.A.; Beattie, C.E.; Bertollo, M.; Pompa, D. The Relationship Between Playing Formations, Team Ranking, and Physical Performance in the Serie a Soccer League. Sports 2024, 12, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgnach, C.; Poser, S.; Bernardini, R.; Rinaldo, R.; di Prampero, P.E. Energy Cost and Metabolic Power in Elite Soccer: A New Match Analysis Approach. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, P.; Iaia, F.M.; Alberti, G.; Strudwick, A.J.; Atkinson, G.; Gregson, W. Monitoring Training in Elite Soccer Players: Systematic Bias between Running Speed and Metabolic Power Data. Int. J. Sports Med. 2013, 34, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stølen, T.; Chamari, K.; Castagna, C.; Wisløff, U. Physiology of Soccer: An Update. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 501–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsbo, J.; Iaia, F.M.; Krustrup, P. Metabolic Response and Fatigue in Soccer. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2007, 2, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujika, I.; Santisteban, J.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Castagna, C. Fitness Determinants of Success in Men’s and Women’s Football. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryściak, J.; Maly, T.; Tomczak, M.; Modric, T.; Malone, J.; Zahálka, F.; Clarup, C.; Phillips, K.; Andrzejewski, M. Relationship between Aerobic Performance and Match Running Performance in Elite Soccer Players Including Playing Position and Contextual Factors. Biol. Sport 2025, 43, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulupınar, S.; Özbay, S.; Gençoğlu, C.; Hazır, T. Low-to-Moderate Correlations Between Repeated Sprint Ability and Aerobic Capacity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Strength Cond. J. 2023, 45, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laterza, F.; Savoia, C.; Bovenzi, A.; D’Onofrio, R.; Pompa, D.; Annino, G.; Manzi, V. Influence of Substitutions and Roles on Kinematic Variables in Professional Soccer Players. Int. J. Sports Med. 2024, 45, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, V.; Impellizzeri, F.; Castagna, C. Aerobic Fitness Ecological Validity in Elite Soccer Players: A Metabolic Power Approach. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakidis, N.D.; Bishop, C.; Beato, M.; Turner, A.N. Assessment of Aerobic Fitness and Repeated Sprint Ability in Elite Male Soccer: A Systematic Review of Test Protocols Used in Practice and Research. Sports Med. 2025, 55, 1233–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsbo, J. Fitness Training in Football: A Scientific Approach; August Krogh Institute, University of Copenhagen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1994; ISBN 978-87-983350-7-8. [Google Scholar]

- Padulo, J.; Buglione, A.; Larion, A.; Esposito, F.; Doria, C.; Čular, D.; di Prampero, P.E.; Peyré-Tartaruga, L.A. Energy Cost Differences Between Marathon Runners and Soccer Players: Constant Versus Shuttle Running. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1159228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, C.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Chamari, K.; Carlomagno, D.; Rampinini, E. Aerobic Fitness and Yo-Yo Continuous and Intermittent Tests Performances in Soccer Players: A Correlation Study. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2006, 20, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.C.R.; John, G.; Ahmetov, I.I. Testing in Football: A Narrative Review. Sports 2024, 12, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger, L.; Gadoury, C. Validity of the 20 m Shuttle Run Test with 1 Min Stages to Predict VO2max in Adults. Can. J. Sport Sci. J. Can. Sci. Sport 1989, 14, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Paliczka, V.J.; Nichols, A.K.; Boreham, C.A. A Multi-Stage Shuttle Run as a Predictor of Running Performance and Maximal Oxygen Uptake in Adults. Br. J. Sports Med. 1987, 21, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsbottom, R.; Brewer, J.; Williams, C. A Progressive Shuttle Run Test to Estimate Maximal Oxygen Uptake. Br. J. Sports Med. 1988, 22, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger, L.A.; Mercier, D.; Gadoury, C.; Lambert, J. The Multistage 20 Metre Shuttle Run Test for Aerobic Fitness. J. Sports Sci. 1988, 6, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Castagna, C.; Krustrup, P.; Wong, D.P.; Póvoas, S.; Boullosa, D.; Xu, K.; Cuk, I. Exploring the Use of 5 Different Yo-Yo Tests in Evaluating O2max and Fitness Profile in Team Sports: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2025, 35, e70054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoç, B.; Akalan, C.; Alemdaroğlu, U.; Arslan, E. The Relationship Between the Yo-Yo Tests, Anaerobic Performance and Aerobic Performance in Young Soccer Players. J. Hum. Kinet. 2012, 35, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining Training and Performance Caliber: A Participant Classification Framework. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, H.; Monahan, K.D.; Seals, D.R. Age-Predicted Maximal Heart Rate Revisited. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffield, R.; Dawson, B.; Pinnington, H.C.; Wong, P. Accuracy and Reliability of a Cosmed K4b2 Portable Gas Analysis System. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2004, 7, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Prampero, P.E.; Peeters, L.; Margaria, R. Alactic O 2 Debt and Lactic Acid Production after Exhausting Exercise in Man. J. Appl. Physiol. 1973, 34, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsen, E.; Hem, E.; Anderssen, S.A. End Criteria for Reaching Maximal Oxygen Uptake Must Be Strict and Adjusted to Sex and Age: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 19–27, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Measuring Agreement in Method Comparison Studies. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 1999, 8, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamparo, P.; Pavei, G.; Nardello, F.; Bartolini, D.; Monte, A.; Minetti, A.E. Mechanical Work and Efficiency of 5 + 5 m Shuttle Running. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 116, 1911–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Léger, L.A.; Lambert, J. A Maximal Multistage 20-m Shuttle Run Test to Predict VO2 Max. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1982, 49, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoia, C.; Padulo, J.; Colli, R.; Marra, E.; McRobert, A.; Chester, N.; Azzone, V.; Pullinger, S.A.; Doran, D.A. The Validity of an Updated Metabolic Power Algorithm Based upon Di Prampero’s Theoretical Model in Elite Soccer Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buglione, A.; di Prampero, P.E. The Energy Cost of Shuttle Running. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 113, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNarry, M.A.; Wilson, R.P.; Holton, M.D.; Griffiths, I.W.; Mackintosh, K.A. Investigating the Relationship between Energy Expenditure, Walking Speed and Angle of Turning in Humans. PloS ONE 2017, 12, e0182333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaria, R.; Cerretelli, P.; Aghemo, P.; Sassi, G. Energy Cost of Running. J. Appl. Physiol. 1963, 18, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falch, H.N.; Rædergård, H.G.; van den Tillaar, R. Effect of Approach Distance and Change of Direction Angles Upon Step and Joint Kinematics, Peak Muscle Activation, and Change of Direction Performance. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 594567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, T.; Hirai, S.; Anbe, Y.; Takai, Y. A New Approach to Quantify Angles and Time of Changes-of-Direction during Soccer Matches. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.J.; Jordan, A.R.; Kiely, J. Relationships Between Eccentric and Concentric Knee Strength Capacities and Maximal Linear Deceleration Ability in Male Academy Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loturco, I.; Pereira, L.A.; Reis, V.P.; Abad, C.C.C.; Freitas, T.T.; Azevedo, P.H.S.M.; Nimphius, S. Change of Direction Performance in Elite Players from Different Team Sports. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 862–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keiner, M.; Warneke, K.; Skratek, J.; Kadlubowski, B.; Beinert, K.; Wittke, A.; Wirth, K. Specificity in Change of Direction Training: Impact on Performance Across Different Tests. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2025, 39, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Krustrup, P.; Mohr, M.; Amstrup, T.; Rysgaard, T.; Johansen, J.; Steensberg, A.; Pedersen, P.K.; Bangsbo, J. The Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test: Physiological Response, Reliability, and Validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, M.D.; Calleja-Gonzaòez, J.; Mikic, M.; Madic, D.M.; Drid, P.; Vuckovic, I.; Ostojic, S.M. Accuracy and Criterion-Related Validity of the 20M Shuttle Run Test in Well-Trained Young Basketball Players. Monten. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2016, 5, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, L.; Martinez, G.; Morrone, M.; Boi, A.; Meloni, M.; Perroni, F.; Donadu, M.G.; Deriu, F.; Manca, A. Adjusting the Yo-Yo IRT-1 Equation to Estimate VO2max of Sub-Elite Football Referees: A Gender-Comparative Study. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2025, 65, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, M.W.; Baumgart, C.; Slomka, M.; Polglaze, T.; Freiwald, J. Variability of Metabolic Power Data in Elite Soccer Players During Pre-Season Matches. J. Hum. Kinet. 2017, 58, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shushan, T.; Lovell, R.; Buchheit, M.; Scott, T.J.; Barrett, S.; Norris, D.; McLaren, S.J. Submaximal Fitness Test in Team Sports: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Exercise Heart Rate Measurement Properties. Sports Med. Open 2023, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dello Iacono, A.; Martone, D.; Cular, D.; Milic, M.; Padulo, J. Game Profile-Based Training in Soccer: A New Field Approach. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 3333–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompa, D.; Caporale, A.; Carson, H.; Beato, M.; Bertollo, M. Influence of the Constraints Associated with the Numerical Game Situations on the Technical-Tactical Actions of U-11 Football Players in Spain: A Commentary on Garcia-Angulo et al. (2024). Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2024, 19, 2530–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziogas, G.G.; Patras, K.N.; Stergiou, N.; Georgoulis, A.D. Velocity at Lactate Threshold and Running Economy Must Also Be Considered along with Maximal Oxygen Uptake When Testing Elite Soccer Players during Preseason. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandford, G.N.; Laursen, P.B.; Buchheit, M. Anaerobic Speed/Power Reserve and Sport Performance: Scientific Basis, Current Applications and Future Directions. Sports Med. Auckl. NZ 2021, 51, 2017–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, J.; Montiel-Rojas, D.; Romare, M.G.A.; Johansson, E.; Folkesson, M.; Pernigoni, M.; Frolova, A.; Brazaitis, M.; Venckunas, T.; Ponsot, E.; et al. Cold- and Hot-Water Immersion Are Not More Effective than Placebo for the Recovery of Physical Performance and Training Adaptations in National Level Soccer Players. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 125, 3179–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shushan, T.; McLaren, S.J.; Buchheit, M.; Scott, T.J.; Barrett, S.; Lovell, R. Submaximal Fitness Tests in Team Sports: A Theoretical Framework for Evaluating Physiological State. Sports Med. Auckl. NZ 2022, 52, 2605–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| YYET | YYIET | YYIRT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modalities | Continuous running | 5-s active break between each 40-m run | 10-s active break between each 40-m run |

| Level 1 | Starting at 8 km·h−1 | Starting at 8 km·h−1 | Starting at 10 km·h−1 |

| Level 2 | Starting at 11.5 km·h−1 | Starting at 11.5 km·h−1 | Starting at 13 km·h−1 |

| Measured | Pre-Season (July) | In-Season (January) | Mean Difference | Effect Size (Qualitative Interpretation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured O2max (mL·kg−1·min−1) | 53.04 ± 4.35 | 60.41 ± 4.78 * | +13.90% (CI 5.56–9.18) | 2.09 (large) |

| Estimated O2max (mL·kg−1·min−1) | 50.74 ± 4.21 | 53.40 ± 3.53 * | +5.24% (CI 1.46–3.86) | 1.14 (large) |

| YYET1 Distance (m) | 2064.71 ± 288.32 | 2247.06 ± 241.65 * | +8.83% (CI 100.02–264.69) | 1.14 (large) |

| YYET1 Speed (km·h−1) | 13.51 ± 0.65 | 13.91 ± 0.52 * | 2.96% (CI 0.21–0.59) | 1.10 (large) |

| HRpeak (bpm) | 190.65 ± 8.98 | 187.53 ± 6.87 * | −1.64% (CI −5.37–−0.89) | −0.71 (medium) |

| postBLA (mmol·L−1) | 8.11 ± 1.70 | 7.95 ± 1.16 | −1.97% (CI −1.19–−0.86) | −0.08 (trivial) |

| Ve (L·min−1) | 138.66 ± 18.21 | 151.99 ± 10.40 * | 9.61% (CI 5.70–20.97) | 0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buglione, A.; Pompa, D.; Beato, M.; Rocchi, M.B.L.; Savoia, C.; Bertollo, M.; Curzi, D.; Sisti, D.; Perroni, F.

Measured vs. Estimated

Buglione A, Pompa D, Beato M, Rocchi MBL, Savoia C, Bertollo M, Curzi D, Sisti D, Perroni F.

Measured vs. Estimated

Buglione, Antonio, Dario Pompa, Marco Beato, Marco Bruno Luigi Rocchi, Cristian Savoia, Maurizio Bertollo, Davide Curzi, Davide Sisti, and Fabrizio Perroni.

2025. "Measured vs. Estimated

Buglione, A., Pompa, D., Beato, M., Rocchi, M. B. L., Savoia, C., Bertollo, M., Curzi, D., Sisti, D., & Perroni, F.

(2025). Measured vs. Estimated