Abstract

Physical activity integration in elementary education seeks to promote academic performance and the physical, emotional and social health of students. This study aims to examine the effect of active methodologies involving physical activity in primary school students through a detailed review of the scientific literature. A systematic review was conducted regarding PRISMA guidelines. Searches were performed in Web of Science, Scopus and SPORTDiscus. Studies published between 2018 and April 2024 were selected. The studies focused on the application of active methodologies in primary school populations. The quality of the studies was assessed using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Articles from Various Fields. After screening and review, 22 articles were included. Most of the studies had longitudinal quasi-experimental or repeated measures designs with a randomized cluster-controlled pilot trial. Cross-sectional studies with descriptive data and mixed methods were also included. Cooperative learning and active breaks were found to improve engagement, classroom behavior, and academic outcomes. In addition, gamification and challenge-based learning also showed positive effects on motivation and engagement, although these were more context-dependent. Shorter or small-scale interventions produced promising but less robust results. Active methodologies improve primary education outcomes, but inconsistent designs limit generalization.

1. Introduction

Primary education is a key stage in children’s integral development, as it encompasses not only academic learning but also emotional, social, and physical growth [1]. During this period, educators must employ pedagogical strategies that promote the holistic development of students. In this context, active methodologies have emerged as an innovative approach to optimize the teaching- learning process, as they encourage active participation, critical thinking and collaboration, which are fundamental aspects for developing transversal competences in students [2]. Within these methodologies, the incorporation of physical activity plays a central role, since movement-based approaches not only stimulate cognitive engagement but also contribute directly to students’ physical health and socio-emotional development. This is particularly relevant in primary education, where reducing sedentary behavior and integrating structured opportunities for movement can enhance classroom climate, motivation, and academic outcomes. Consequently, the present study focuses specifically on the application of physically active methodologies in primary school contexts, examining how innovative pedagogical strategies that embed movement into the curriculum impact children aged 6 to 12.

Active methodologies, also referred to here as “practice-oriented pedagogical approaches,” are student-centered strategies in which learners actively construct knowledge through hands-on, collaborative, and reflective activities, guided by the teacher [3]. These approaches align with constructivist theory, which conceptualizes learning as an active and contextualized process; socio-cultural theory, which emphasizes the role of social interaction and scaffolding in cognitive development; and self-determination theory, which highlights the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness for fostering intrinsic motivation and engagement [4,5,6]. By fostering inquiry, problem-solving, and experiential learning, practice-oriented approaches differ from traditional didactic instruction, positioning students as protagonists in their own learning. These methodologies can be classified into several categories according to the approach they use. For instance, project-based learning encourages students to work on extended projects that require applying knowledge and skills to produce a concrete outcome. Similarly, gamification incorporates the dynamics and mechanics of games into non-playful contexts to foster motivation and engagement in the learning process [7].

It is important to note, however, that the concept of active learning should not be conflated with Physically Active Learning (PAL). While active learning broadly refers to pedagogical approaches that promote student participation and engagement in constructing knowledge, PAL specifically describes the integration of physical activity into academic instruction as a means of enhancing learning and health outcomes. Recent systematic reviews emphasize that PAL is rooted in both educational and movement sciences, and has its own body of evidence showing positive effects on cognitive performance, classroom behavior, and motivation [8,9]. Therefore, in this article, we distinguish between these traditions: active learning as a wider pedagogical paradigm, and PAL as a particular strand that combines curricular content with physical activity.

Research demonstrates that integrating classroom-based physical activity—such as movement-infused lessons—can yield modest yet significant improvements in children’s on-task behavior and academic performance [9]. Moreover, when compared to traditional sedentary classrooms, physically active lessons produced a small positive effect on academic outcomes [8]. Broad meta-analytic evidence further supports that incorporating moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (20–44 min, three times per week) with academic content enhances working memory, fluid intelligence, and math achievement [10,11].

Active methodologies are a set of student-centered pedagogical approaches in which the teacher guides and facilitates the learning process. This type of methodology encourages students’ active participation in the construction of their own knowledge through practical, collaborative, and reflective activities [3]. In contrast to traditional methodologies, where the student assumes a passive role and is the receiver of information, in active methodologies, the student is the main protagonist of learning [12]. These methodologies can be classified into several categories according to the approach they use: cooperative learning, project- or challenge-based learning, gamification, and those that integrate movement and physical activity as part of the educational process [13].

Research has shown the positive impact of active methodologies on different aspects of children’s development, including academic performance, social skills, learning autonomy, and student motivation [14]. Methodologies that integrate movement and physical activity, such as active breaks or dynamic play, have been shown to improve concentration, emotional well-being, and class participation, contributing to a more enriching and healthy educational experience [15,16].

Active methodologies play a fundamental role in promoting physical, cognitive, and emotional development through movement in physical education. This approach recognizes that PE is not only limited to the sporting aspect but also encompasses a broader dimension of holistic student development [17]. Examples of these methodologies include cooperative learning, where students work together to achieve common goals through physical activities; the teaching model of personal and social responsibility, which uses physical activity to foster decision-making, conflict resolution, and self-control skills; and introjective motor practices, which combine physical development with mental well-being through activities such as yoga and dance [12,18].

The implementation of these methodologies in education not only improves academic results but also has a positive impact on students’ physical and mental health. According to Pastor-Vicedo et al. [19], active methodologies that integrate movement can reduce sedentary lifestyles in the school environment, promote healthy habits from an early age, and foster a dynamic and motivating learning environment. In addition, recent research highlights the value of gamification and educational games, which combine playful activities with the teaching of academic concepts, allowing students to learn in a fun and active way [20].

In short, the use of active methodologies, particularly those that incorporate physical activity, offers multiple benefits in the school environment, contributing not only to academic development but also to students’ overall well-being. Recent evidence suggests that these benefits may be explained by mechanisms such as improvements in executive functions (e.g., working memory and inhibitory control), enhanced emotional regulation, and increased classroom engagement and time on task [8,21]. Nevertheless, despite these promising findings, further research is still required to determine how such methodologies can be effectively adapted to diverse educational contexts and student populations, and to disentangle the relative contribution of these mechanisms to learning and development [22]. In this sense, the present review aims not only to synthesize the existing evidence on active methodologies in education but also to critically examine the theoretical and empirical explanations proposed for their impact, thereby identifying current gaps and guiding future lines of research.

Therefore, the aim of this article is to analyze the impact of the use of active methodologies involving physical activity in primary school students through the synthesis and critical analysis of existing studies to identify trends, patterns, and areas of consensus in current research, as well as to highlight limitations and areas of opportunity for future research in this field.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was prospectively registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) international database (ID: 1143791). It examined and analyzed previous research on the impact of active methodologies incorporating physical activity on the cognitive, social, emotional, and physical development of primary school students. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [23] and the practical guide for systematic reviews, with or without meta-analysis [24], were used to guide the methodological process. The completed PRISMA check-list is provided in the Supplementary File S1.

This work was conducted through a systematic review that examined and analyzed previous research on the impact of active methodologies incorporating physical activity on the cognitive, social, emotional, and physical development of primary school students.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [23] and the practical guide for systematic reviews, with or without meta-analysis [24], were used for this purpose.

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

- (a)

- Time range: Articles published between 2018 and April 2024 were included. This time frame was chosen not only to ensure the inclusion of recent and pertinent studies, but also because bibliometric analyses across databases such as Scopus and Web of Science have shown an exponential increase in research related to physical activity and active learning during this period. For instance, Scopus data reveal that annual publications mentioning ‘physical activity’ surged from approximately 5876 per year in 2001–2017 to around 15,812 per year in 2017–2022—a near three-fold increase—while Web of Science exhibited very similar relative growth.

- (b)

- Availability of the full text of the reviewed studies.

- (c)

- Languages: The articles had to be written in English, Spanish, or Portuguese to cover a broad base of scientific literature in these languages academic field.

- (d)

- Definition of active methodologies related to physical activity: Studies implementing active methodologies specifically linked to physical activity were included. This includes pedagogical interventions that integrate physical movement as part of the teaching- learning process, such as active breaks, learning based on dynamic games, gamification with physical components, or motor activities designed to reinforce academic concepts. While active methodologies cover a wide spectrum of approaches, this study limited the review to those that explicitly incorporate physical activity as a fundamental component.

- (e)

- Target population: Only studies on primary school students were included, in order to specifically analyze the impact of these methodologies at this educational stage.

Study designs were not treated as a separate inclusion criterion; rather, a range of designs—including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental studies, longitudinal observational studies, and cross-sectional analyses—were purposely considered. This inclusive approach reflects the theoretical relevance of integrating both experimental evidence, which supports causal inference, and ecological insights from observational research to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the impact of physically active methodologies.

The manuscripts were selected according to the following criteria: The bibliographic references of the selected articles were reviewed to identify additional studies that met the same inclusion criteria.

2.2. Search Strategy

A systematic review was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines [23]. Following the Patient/Problem, Intervention, Comparison y Outcome (PICO) strategy [25], the following search formula was used: ((“active method*”) AND (“physical education” OR “phys ed”) AND (elementary school OR primary school OR grade school)). Then, the exploration of articles in three database platforms (Web of Science, Scopus, and SPORTDiscus) was conducted from 1 March to 15 April 2024. This scan was organized into three areas: (1) active methodologies; (2) physical education or physical activity; and (3) intervention, experiment, quasi-experiment, RC trial, or descriptive study. Once the search was completed, duplicates were eliminated.

2.3. Study Selection and Processing of Data

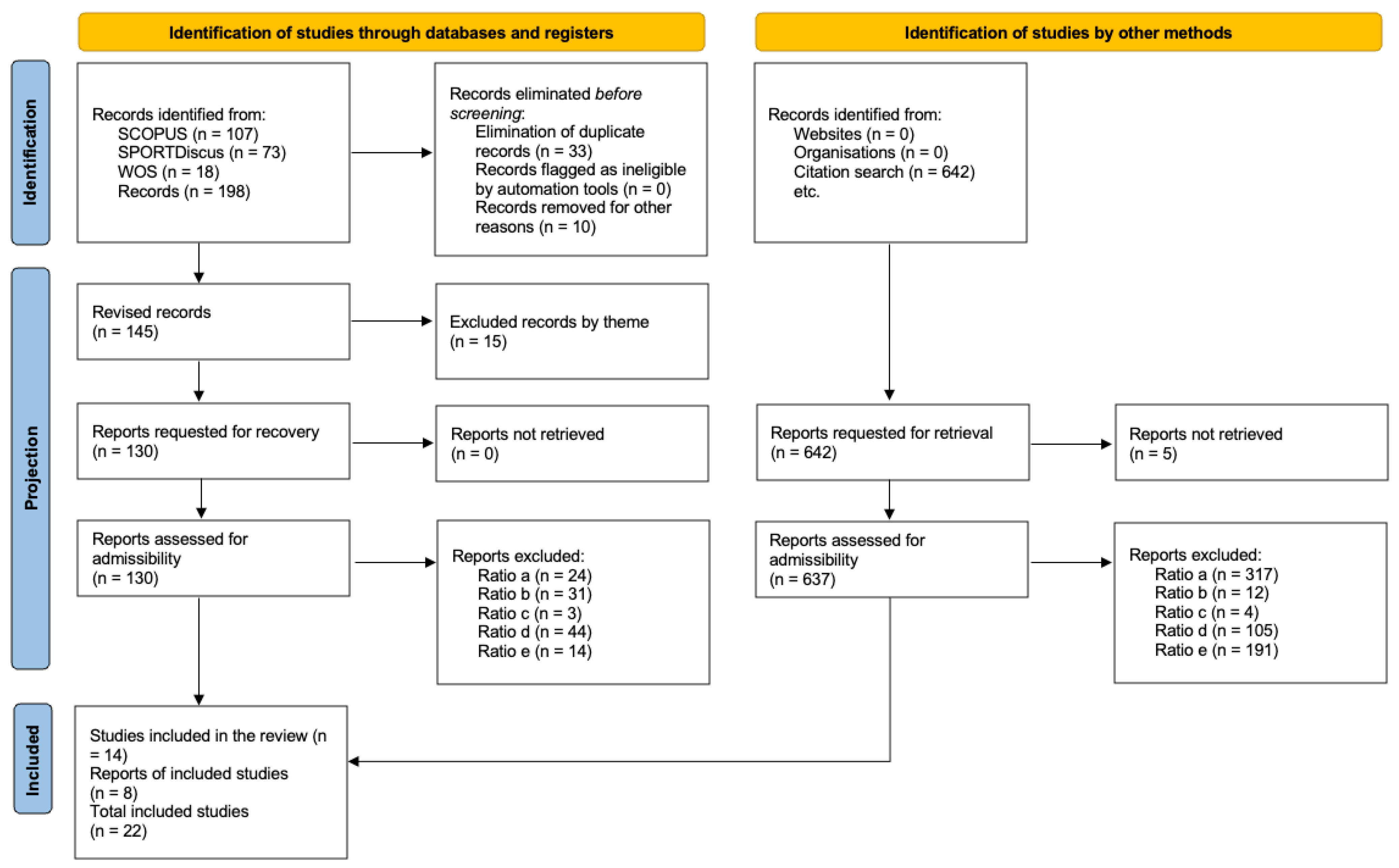

After completing the article search, both titles and abstracts were reviewed to identify relevant articles and exclude those that did not meet the inclusion criteria. As a result, 22 studies were selected for detailed analysis, focusing on the theme of active methodologies related to physical activity. A top-down search was then conducted by examining the bibliographic references of the included articles, which led to the incorporation of eight additional studies cited in the original papers. Figure 1 shows a flow chart illustrating the process of selecting the articles in the sample.

Figure 1.

Flowchart.

2.4. Quality Assessment

The quality of the selected studies was assessed using a standardized tool, as summarized below (Table 1):

Table 1.

Summary of the quality assessment procedure for included studies.

The quality of the articles was assessed using the “Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields” tool [27]. This tool consists of 14 items addressing aspects such as research design, sample characteristics, methodology employed, data analysis, and results and conclusions presentation. Each item was rated in terms of satisfaction, with values of 2 (satisfactory), 1 (partially satisfactory), 0 (not satisfactory), and 0 (not applicable). The final score was calculated by adding twice the number of satisfactory items plus the value of partially satisfactory items and dividing the result by 28 minus twice the number of non-applicable items. These scores were expressed as percentages ranging from 0% to 100%. Two researchers independently conducted the assessment to ensure objectivity.

2.5. Data Collection

In the first phase, data were collected from the selected articles, followed by a thorough verification of the information according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Particular attention was paid to details related to participants, intervention, comparisons, outcomes, and study design, all of which were in line with the indicated structure. This task was carried out by two experts in the field to ensure consistency in coding and to determine the degree of agreement between researchers in terms of data extraction and selection [28]. A 95% level of agreement was achieved in the classification of articles, which was calculated by multiplying the number of matches by 100 and dividing it by the total number of categories defined for each study, followed by another multiplication by 100. In cases of disagreement, the two researchers discussed the discrepancies and reached a consensus through consultation with a third independent expert, ensuring that the final data selection and coding were accurate and reliable.

3. Results

3.1. Quality of the Studies

Article quality scores were expressed as percentages, ranging from 0 to 100%, ranging from 0.79 to 1 (Table 2). Inter-rater agreement was calculated using the intra-class correlation coefficient, yielding a score of 0.904 (p < 0.001), indicating excellent agreement [20]. After implementing inter-rater agreement, a conservative cut-off point was agreed upon for the selection of raters, including studies with scores of 65% (>0.65). The overall scores ranged from 0.79 to 1 (first observer) and 0.71 to 1 (second observer).

Table 2.

Assessment of the study quality.

3.2. Study Results

To present the main characteristics of the study sample, the data from the articles were coded based on the following units of analysis: (1) Author/s; (2) Country; (3) Context; (4) Subjects; (5) Age; (6) Methodology; (7) Type of study; (8) Duration; and (9) Protocol (Table 3).

Table 3.

The main characteristics of the study sample.

For a comprehensive analysis of the results presented in Table 3 and to avoid an over-generalized view of the active methodologies, we can divide the analysis into blocks. This approach will allow for an in-depth analysis of the differences and similarities between the methodologies implemented and the results obtained.

3.2.1. Block 1: Cooperative Methodologies, Gamification and PBL

This block includes studies that have implemented pedagogical strategies that encourage social interaction, cooperation, and Project-Based Learning (PBL). These methodologies were considered movement-based because they intentionally integrate bodily activity into the learning process, either through motor dynamics in cooperative tasks, embodied challenges in gamification, or hands-on, kinesthetic activities in project development. They stand out for their emphasis on students’ active participation and joint work:

- Cañabate et al. (2023) [29];

- Menéndez Santurio (2023) [31]

Nevertheless, short duration and limited samples reduce comparability and limit conclusions on long-term impact.

3.2.2. Block 2: Active Breaks and Didactic Games

This block groups studies that have used active breaks or didactic games as interventions to interrupt sedentary behavior and improve cognitive and physical performance:

- González-Fernández et al. (2023) [30];

- Jiménez-Parra et al. (2022) [33] and Méndez-Giménez et al. (2022) [36];

- Watson et al. (2019) [44]

While most studies reported positive effects, some interventions showed only modest or null changes, particularly when protocols were short or inconsistently applied.

3.2.3. Block 3: Hybrid Models and Innovative Techniques (Flipped Learning, Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility)

This block includes studies that have integrated different active methodologies and innovative pedagogical techniques:

- Botella et al. (2021) [37];

- Muñoz-Parreño et al. (2021) [38];

- Jiménez-Parra et al. (2023) [12]

The heterogeneity of designs makes cross-study comparison difficult, and weaker study designs temper the strength of evidence.

3.2.4. Block 4: Long-Term and Longitudinal Intervention Models

This block groups together studies that applied long-term interventions (more than 6 months), providing a long-term view of the effects of active methodologies:

- Klizienė, Kimantienė et al. (2018) [47] and Klizienė et al. (2018) [48];

- Popa and Popa (2018) [49]

Despite promising outcomes, the limited number of large-scale randomized controlled trials highlights the need for stronger evidence on sustainability.

In summary, the implementation of active methodologies varies significantly in terms of duration, type of intervention, and expected outcomes. Each methodology has a different approach, which makes it difficult to generalize results, as the benefits and impact largely depend on how each approach is applied, the duration of the intervention and the context in which it is developed.

A review of the studies included in Table 3 reveals several clear patterns across countries, duration, and methodology types. Most of the research was conducted in Spain, followed by smaller contributions from Chile, Italy, Romania, Lithuania, and Australia, indicating a concentration of studies in Southern Europe. Participant numbers varied widely, ranging from small samples of 19–25 pupils to larger cohorts exceeding 370 participants, reflecting diverse classroom settings and study scales.

Regarding age, the majority of studies focused on primary school children between 6 and 12 years, with the mean age typically around 9–11 years. Study durations were highly variable, spanning short interventions of 4–6 weeks to longitudinal programs lasting up to 9 months, which may affect both the magnitude and sustainability of observed outcomes.

In terms of methodology, a substantial proportion of the studies employed quasi-experimental or longitudinal designs, often with repeated measures or pretest-posttest structures. A smaller number were pilot randomized controlled trials, cross-sectional descriptive, or observational studies. Most interventions integrated physical activity directly into the academic curriculum, using approaches such as active breaks, movement-based learning, cooperative methodologies, gamification with physical components, and structured motor activities linked to curricular content. Several studies combined traditional teaching with these active methodologies, while others implemented entirely new physical-activity-based approaches.

Overall, these patterns suggest that physically active methodologies are primarily applied in European primary education contexts, with interventions targeting core primary age groups, variable durations, and a range of methodological designs that support both experimental inference and ecological validity. This synthesis complements the detailed information presented in Table 3 and aids in identifying trends, common practices, and potential gaps for future research.

Table 4 reflects a wide variety of active approaches and methodologies applied in the field of PE, with results varying according to each study’s treatment variables and objectives. Each active methodology has particular characteristics that affect its implementation and the obtained results. Following this recommendation, a descriptive and analytical analysis by blocks is presented below.

Table 4.

Treatment variables and main outcomes.

Block 1: Cooperative and participatory methods

Studies that apply cooperative learning and interdisciplinary programs, such as the Active Values Programme, are notable for their emphasis on social and emotional development. Cañabate et al. [37] pointed out that both cooperative and competitive learning are effective in improving participation and motor performance, with gender differences indicating that boys make more progress in competitive contexts, while the cooperative method is equally effective for both genders. This observation reinforces the idea that the methodology must be adjusted to the characteristics of the group and that the effectiveness of cooperative methodologies is not uniform.

Jiménez-Parra et al. [12] demonstrated that interdisciplinary programs, which combine pedagogical models with active methodologies can contribute to the integral development of pupils, not only physically but also cognitively and socially. This approach underlines the importance of a deeper analysis of interdisciplinarity’s benefits, as its implementation goes beyond the simple use of active techniques: it seeks a holistic impact.

Block 2: Gamification and educational games

As demonstrated in Menéndez-Santurio’s study [31], gamification is a methodology that significantly increases fun, cooperative, and academic learning. These results are not surprising, as gamification is perceived as a more interactive and motivating experience. However, this approach requires further analysis as to how the balance between fun and educational goals can be maintained, as the perception of fun does not always translate directly into better academic outcomes.

Didactic games, used by Yáñez-Sepúlveda et al. [32], have shown a positive impact on the teaching of hygiene habits, highlighting the relevance of games as effective tools for cross-curricular learning. This raises questions about the applicability of didactic games in other more complex areas of the school curriculum and how these methodologies can foster long-term retention of learning.

Block 3: Active breaks

Several studies, such as González-Fernández et al. [30], Jiménez-Parra et al. [33], and Muñoz-Parreño et al. [38], agree that active breaks have positive effects in multiple areas, from improving response time and alertness to increasing physical activity and academic performance. In particular, 10 min breaks are reported to improve efficacy in 10–11 years old schoolchildren and contribute to classroom climate and the reduction in disruptive behavior.

Such interventions, while effective in improving variables such as alertness and motor skills, need to be contextualized. Not all populations or age groups may respond in the same way, so the methodology must be adjusted according to the educational environment. Furthermore, investigating whether the implementation of active breaks has a sustained effect over time or whether its impact is rather temporary would be interesting.

Block 4: Application of responsibility models and active methodologies to the school curriculum

The Personal and Social Responsibility Model applied by Manzano and Valero-Valenzuela [35] and Escartí et al. [45] shows that this methodology, when extended to different subjects, can significantly improve responsibility, autonomy, motivation, and the social climate of the classroom. However, this model requires more structured and consistent implementation to ensure that its benefits are sustained in the long term. Although the results are promising, the success of these programs depends on teacher training and commitment, which raises the challenge of scalability and implementation fidelity.

4. Discussion

The results provide a comprehensive view of how various active methodologies implemented in educational settings, specifically in primary education, can influence student development in various aspects. Importantly, physical activity emerges as the central component driving these outcomes, rather than merely a complementary element, underpinning both cognitive and socio-emotional benefits. These findings add to the growing evidence supporting the effectiveness of physical activity-based educational practices.

By comparing the results of these studies with those of previous research that addressed the same variables using different active methodologies, additional conclusions can be drawn about the relative effectiveness of each approach. For example, the implementation of programs such as cooperative learning and active breaks has been shown to improve engagement, motor performance, and learning effectiveness [29,30], results consistent with previous research that has highlighted the benefits of these practices [50,51].

Gamification has emerged as a promising active methodology to improve students’ motivation, engagement, and academic performance [31]. These findings are consistent with those of previous research that found similar benefits of gamification in different educational contexts [52,53]. However, as noted by Domínguez et al. [54] and Sailer and Homner [55], the effectiveness of gamification is highly context-dependent, varying according to game design, duration, and students’ prior experience and receptiveness.

Studies investigating the impact of didactic games and challenge-based learning have shown significant improvements in various skills and knowledge, such as motor skills and cross-cutting learning of hygiene habits [32,49]. These findings support the idea that integrating playful and challenging activities into the school curriculum can improve student participation and engagement while promoting the development of key cognitive and social skills [56].

Finally, results from studies investigating the implementation of the TPSRM have highlighted improvements in student responsibility, autonomy, and motivation, as well as in the classroom social climate [33,45]. These findings are consistent with previous research that has demonstrated the benefits of the TPSR approach in promoting SES and improving school climate [57,58].

It is important to acknowledge the substantial heterogeneity among the included studies, which varied in country, sample size, duration, and type of active methodology applied. Most studies were conducted in Spain, with fewer contributions from Chile, Italy, Romania, Lithuania, and Australia, which limits the generalisability of the findings to other educational contexts. Sample sizes were often small, and intervention durations ranged from a few weeks to several months, potentially influencing the magnitude and sustainability of the observed effects. This variability underscores the need for caution when extrapolating results to different populations and educational systems [8,21]. This underscores the need to interpret results cautiously, particularly in cross-cultural applications.

Potential sources of bias should also be considered. Publication bias may overestimate positive effects, while small sample sizes and the absence of long-term follow-up in many studies limit the strength of the conclusions. Additionally, differences in how active methodologies were implemented—such as variations in intensity, frequency, and fidelity of the intervention—may have influenced outcomes and introduced further variability [9,10].

When situating these findings within the broader international debate on physically active learning (PAL), our results generally align with meta-analyses demonstrating small to moderate improvements in academic performance, executive function, and classroom engagement associated with PAL interventions [8,9,59]. Nonetheless, some discrepancies exist, particularly regarding the long-term impact and the optimal combination of methodologies, highlighting the need for further high-quality, longitudinal research across diverse educational settings.

These findings highlight the importance of using active teaching methods that include physical activity in schools to promote students’ holistic development. Although each active methodology has its advantages and challenges, evidence shows that it can improve academic performance, physical and emotional health, and overall student well-being.

In interpreting these findings, it is also important to consider the methodological and contextual limitations of the included studies. Several interventions received lower quality scores due to small sample sizes, absence of randomization, or lack of long-term follow-up, which limits both statistical power and the robustness of causal inferences. Moreover, the predominance of Spanish and European studies introduces a cultural bias, making it difficult to generalize outcomes internationally. Potential confounding factors—such as socio-economic background, quality of teacher training, and differences in curricular contexts—were rarely controlled for, yet these are likely to moderate the effectiveness of active methodologies. In comparative terms, cooperative learning and active breaks appear more consistently beneficial across outcomes and contexts, whereas gamification and challenge-based learning show greater variability depending on design and implementation. These considerations underscore the need for caution in interpretation and highlight the importance of designing future interventions that are not only methodologically rigorous but also sensitive to cultural and contextual diversity. Taken together, these limitations emphasize the need for balanced interpretations and for future research that systematically addresses these methodological and contextual challenges.

More research is needed to better understand how and why these effects work and to find effective strategies to implement and sustain them in the long term. Future studies should focus on standardizing intervention protocols, exploring long-term outcomes, and including larger, more representative samples to strengthen the evidence base. It is also important to keep in mind the limitations of these studies, such as the difficulty of generalizing results due to differences in how methodologies are applied and possible bias in some research. Future combinations of active methods, the use of new technologies, and the adaptation of approaches for students with special needs should be considered. From an educational point of view, it is essential that teachers receive ongoing training in active methodologies, that these practices are included in curricula, and that teachers and policy makers collaborate to create schools that promote effective and sustainable implementation.

5. Conclusions

The studies reviewed show that active methodologies involving physical activity in primary school can have a positive impact on the development of students. In particular, cooperative learning and active breaks stand out as the most consistently supported approaches, with multiple experimental and quasi-experimental studies reporting improvements in physical activity levels, academic performance, and student autonomy. Gamification also shows promise for enhancing motivation and engagement, although its effectiveness appears highly dependent on careful design and implementation. Likewise, the integration of didactic games and challenge-based learning contributes to the development of cognitive and social skills, though the evidence base remains more limited and heterogeneous.

Nevertheless, caution is needed when interpreting these findings. Most studies were conducted in Spain and other European or Latin American countries, which constrains the generalizability of results to broader cultural and educational contexts. Furthermore, the number of large-scale randomized controlled trials remains limited, reducing the strength of causal inferences and the ability to draw firm conclusions about long-term impact.

In conclusion, adopting active approaches to teaching improves not only academic performance but also the overall health and well-being of students, preparing them for future challenges. For educators, this implies the need to systematically integrate movement into classroom routines and curricula, prioritizing evidence-based strategies such as cooperative learning and active breaks. For policymakers, recommendations include embedding physically active learning in educational standards, supporting teacher professional development, and ensuring resources for sustainable implementation. By addressing current methodological gaps and expanding research to diverse contexts, the field can better inform scalable practices that position physical activity as a central driver of holistic student development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sports13100358/s1, File S1: PRISMA_2020_checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F.C.-C. and E.M.-I.; methodology, R.F.C.-C., J.L.U.-J., J.M.A.-V. and E.M.-I.; formal analysis, R.F.C.-C., J.L.U.-J., J.M.A.-V. and E.M.-I.; data curation, J.M.A.-V. and E.M.-I.; writing—original draft preparation, R.F.C.-C., J.L.U.-J., J.M.A.-V. and E.M.-I.; writing—review and editing, R.F.C.-C., J.L.U.-J., J.M.A.-V. and E.M.-I.; visualization, R.F.C.-C., J.L.U.-J., J.M.A.-V. and E.M.-I.; supervision, R.F.C.-C., J.L.U.-J., J.M.A.-V. and E.M.-I.; funding acquisition, J.L.U.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Unit of Excellence of the University Campus of Melilla (University of Granada, Spain). Reference: UCE-PP2024-02.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Correal Gutiérrez, M.; Vega Granda, R. Habilidades Emocionales y Convivencia Escolar: Un Análisis en Estudiantes de Tercero a Quinto de Primaria. Cienc. Lat. Rev. Multi. 2024, 8, 1444–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo-Martínez, H.A.; Rosario-González, J.P.; Bennasar-García, M.I. Uso de las TIC y su influencia en estilos de vidas saludables en los estudiantes. Polo Conoc. 2023, 8, 112–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz, P.J.; Baena, A. Metodologías Activas en Ciencias del Deporte Volumen II; Wanceulen Editorial SL: Algeciras, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, J. To Understand Is to Invent: The Future of Education; Grossman: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.H.; Liu, D.J.; Tlili, A.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M. Handbook on Facilitating Flexible Learning During Educational Disruption: The CHINESE Experience in Maintaining Undisrupted Learning in COVID-19 Outbreak; Smart Learning Institute of Beijing Normal University: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, E.; van Steen, T.; Direito, A.; Stamatakis, E. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of physically active classrooms on educational and enjoyment outcomes in school age children. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, A.; Timperio, A.; Brown, H.; Best, K.; Hesketh, K.D. Effect of classroom-based physical activity interventions on academic and physical activity outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilopoulos, F.; Jeffrey, H.; Wu, Y.; Dumontheil, I. Multi-level meta-analysis of physical activity interventions during childhood: Effects of physical activity on cognition and academic achievement. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 35, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez, C. El aprendizaje cooperativo en educación física: Planteamientos teóricos y puesta en práctica. Acción Mot. 2018, 20, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Parra, J.F.; Belando-Pedreño, N.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. The effects of the ACTIVE VALUES program on psychosocial aspects and executive functions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvaro-Tordesillas, A.; Alonso-Rodríguez, M.; Poza-Casado, I.; Galván-Desvaux, N. Experiencia de gamificación en la asignatura de geometría descriptiva para la arquitectura. Educ. XX1 2020, 23, 373–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learreta, B.; Ruano, K. El Cuerpo Entra en la Clase: Presencia del Movimiento en las Aulas Para Mejorar el Aprendizaje; Narcea Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2021; Volume 171. [Google Scholar]

- Gelabert, J.; Sánchez-Azanza, V.; Palou, P.; Muntaner-Mas, A. Acute effects of active breaks on selective attention in schoolchildren. Rev. Psico. Dep. 2023, 32, 277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, H.J.; Simoni, C.; Fuentes-Rubio, M.; Castillo-Paredes, A. Ludomotricidad y Habilidades Motrices Básicas Locomotrices (Caminar, Correr y Saltar). Una propuesta didáctica para la clase de Educación Física en México. Retos 2022, 44, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.Y.; Oh, P.H. Teaching physical education abroad: Perspectives from host cooperating teachers, local students and Australian pre-service teachers using the social exchange theory. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 136, 104364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovira, G. Prácticas motrices introyectivas: Una vía práctica para el desarrollo de competencias socio-personales. Acción Mot. 2022, 5, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor-Vicedo, J.C.; Prieto-Ayuso, A.; Pérez, S.L.; Martínez-Martínez, J. Descansos activos y rendimiento cognitivo en el alumnado: Una revisión sistemática. Apunts Educ. Fís. Deportes 2021, 37, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousiainen, T.; Kangas, M.; Rikala, J.; Vesisenaho, M. Teacher competencies in game-based pedagogy. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 74, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Pesce, C.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Sánchez-López, M.; Martínez-Hortelano, J.A.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Academic achievement and physical activity: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20171498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, C.N.; Narváez, M.E.; Castillo, D.P.; Tapia, S.R. Metodologías activas en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje: Implicaciones y beneficios. Cienc. Lat. Rev. Cienc. Multi. 2023, 7, 3311–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Santos, C.M.; de Mattos Pimenta, C.A.; Nobre, M.R. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2007, 15, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmet, L.M.; Lee, R.C.; Cook, L.S. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields; Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- González-Valero, G.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; Puertas-Molero, P. Use of meditation and cognitive behavioral therapies for the treatment of stress, depression and anxiety in students. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañabate, D.; Gras, M.E.; Pinsach, L.; Cachón, J.; Colomer, J. Promoting cooperative and competitive physical education methodologies for improving the launch’s ability and reducing gender differences. J. Sport Health Res. 2023, 15, 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fernández, F.T.; Baena-Extremera, A.; Hortigüela-Alcalá, D.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J. Effects of physical active breaks on vigilance performance in schoolchildren of 10–11 years. Hum. Mov. 2023, 24, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez Santurio, J.I. Gamificando Harry Potter: Análisis de un estudio de caso en Educación primaria. Aula Encuentro 2023, 25, 62–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez Sepúlveda, R.A.; Hurtado-Almonacid, J.; Olivares-Arancibia, J.; Cortés-Roco, G.; Gudenschwager Sauca, K.; Añasco-Rodríguez, P.; Trigo-Álvarez, J.; Muñoz-Rojas, C. Efectos de los juegos didácticos en la clase de Educación Física en el logro de aprendizaje trasversal sobre hábitos de higiene escolar en estudiantes de 6 y 7 años. Retos 2023, 49, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Parra, J.F.; Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Camerino, O.; Prat, Q.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Effects of a hybrid program of active breaks and responsibility on the behaviour of primary students: A mixed methods study. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Parra, J.F.; Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Camerino, O.; Castañer, M.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Enhancing Physical Activity in the Classroom with Active Breaks: A Mixed Methods Study. Apunts. Educ. Fís. Deportes 2022, 147, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Parra, J.F.; Belando-Pedreño, N.; López-Fernández, J.; García-Vélez, A.J.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. “ACTIVE VALUES”: An interdisciplinary educational programme to promote healthy lifestyles and encourage education in values—A rationale and protocol study. Appl. Sci. 2023, 12, 8073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Giménez, A.; Pallasá-Manteca, M.; Cecchini, J.A. Effects of Active Breaks on the Primary Students’ Physical Activity. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Fís. Deporte 2022, 22, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, Á.G.; García-Martínez, S.; Molina-García, N.; Olaya-Cuartero, J.; Férriz, A. Flipped Learning to improve students’ motivation in Physical Education. Acta Gymnica 2021, 51, e2021.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Parreño, J.A.; Belando-Pedreño, N.; Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. The effect of an active breaks program on primary school students’ executive functions and emotional intelligence. Psicothema 2021, 33, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañabate, D.; Santos, M.; Rodríguez, D.; Serra, T.; Colomer, J. Emotional self-regulation through introjective practices in physical education. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Parreño, J.A.; Belando-Pedreño, N.; Torres-Luque, G.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Improvements in physical activity levels after the implementation of an active-break-model-based program in a primary school. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calella, P.; Mancusi, C.; Pecoraro, P.; Sensi, S.; Sorrentino, C.; Imoletti, M.; Valerio, G. Classroom active breaks: A feasibility study in Southern Italy. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrescu, T. Influences of Physical Education Lesson Movement Games on the Motor Behavior of Primary School Pupils. Gymnasium 2019, 20 (Suppl. S1), 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano, D.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. El Modelo de Responsabilidad Personal y Social (MRPS) en las diferentes materias de la Educación Primaria y su repercusión en la responsabilidad, autonomía, motivación, autoconcepto y clima social. J. Sport Health Res. 2019, 11, 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, A.; Timperio, A.; Brown, H.; Hesketh, K.D. Process evaluation of a classroom active break (ACTI-BREAK) program for improving academic-related and physical activity outcomes for students in years 3 and 4. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escartí, A.; Llopis-Goig, R.; Wright, P.M. Assessing the implementation fidelity of a school-based teaching personal and social responsibility program in physical education and other subject areas. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2018, 37, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Giménez, A.; Pallasá-Manteca, M. Enjoyment and Motivation in an Active Recreation Program. Apunts. Educ. Fís. Deportes 2018, 134, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klizienė, I.; Kimantienė, L.; Čižauskas, G.; Marcinkevičiūtė, G.; Treigytė, V. Effects of an eight-month exercise intervention programme on physical activity and decrease of anxiety in elementary school children. Balt. J. Sport Health Sci. 2018, 4, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klizienè, I.; Cibulskas, G.; Ambrase, N.; Cizauskas, G. Effects of a 8-Month Exercise Intervention Programme on Physical Activity and Physical Fitness for First Grade Students. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2018, 7, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, C.; Popa, C. Contribution of challenges to children from church education in the physic education and sports lessons. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Ser. Phys. Educ. Sport Sci. Mov. Health 2018, 18 (Suppl. S2), 375–385. [Google Scholar]

- Graupensperger, S.A.; Benson, A.J.; Evans, M.B. Everyone else is doing it: The association between social identity and susceptibility to peer influence in NCAA athletes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 40, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattie, J.; Zierer, K. 10 Mindframes for Visible Learning: Teaching for Success; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Shernoff, D.J.; Rowe, E.; Coller, B.; Asbell-Clarke, J.; Edwards, T. Challenging games help students learn: An empirical study on engagement, flow and immersion in game-based learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, R.N.; Auer, E.M.; Collmus, A.B.; Armstrong, M.B. Gamification science, its history and future: Definitions and a research agenda. Simul. Gaming 2018, 49, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A.; Sáenz-de-Navarrete, J.; De-Marcos, L.; Fernández-Sanz, L.; Pagés, C.; Martínez-Herráiz, J.J. Gamifying learning experiences: Practical implications and outcomes. Comput. Educ. 2013, 63, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, M.; Homner, L. The gamification of learning: A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 32, 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Pérez, M.; Morales-Ramírez, M.E. Los ambientes de aula que promueven el aprendizaje, desde la perspectiva de los niños y niñas escolares. Rev. Electron. Educ. 2015, 19, 132–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D.S.; Wright, P.M. The TPSR alliance: A community of practice for teaching, research and service. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 2016, 87, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinek, T.; Hellison, D. Learning responsibility through sport and physical activity. In Positive Youth Development Through Sport, 2nd ed.; Holt, N.L., Ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Hillman, C.H.; Castelli, D.; Etnier, J.L.; Lee, S.; Tomporowski, P.; Lambourne, K.; Szabo-Reed, A.N. Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: A systematic review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1197–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).