Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed… About the Placenta

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Physiology of the Placenta

2.1. Conception and Implantation

2.2. Maternal–Placental Circulation and Immunity

2.3. Hormonal Secretion

2.4. Placental Barrier

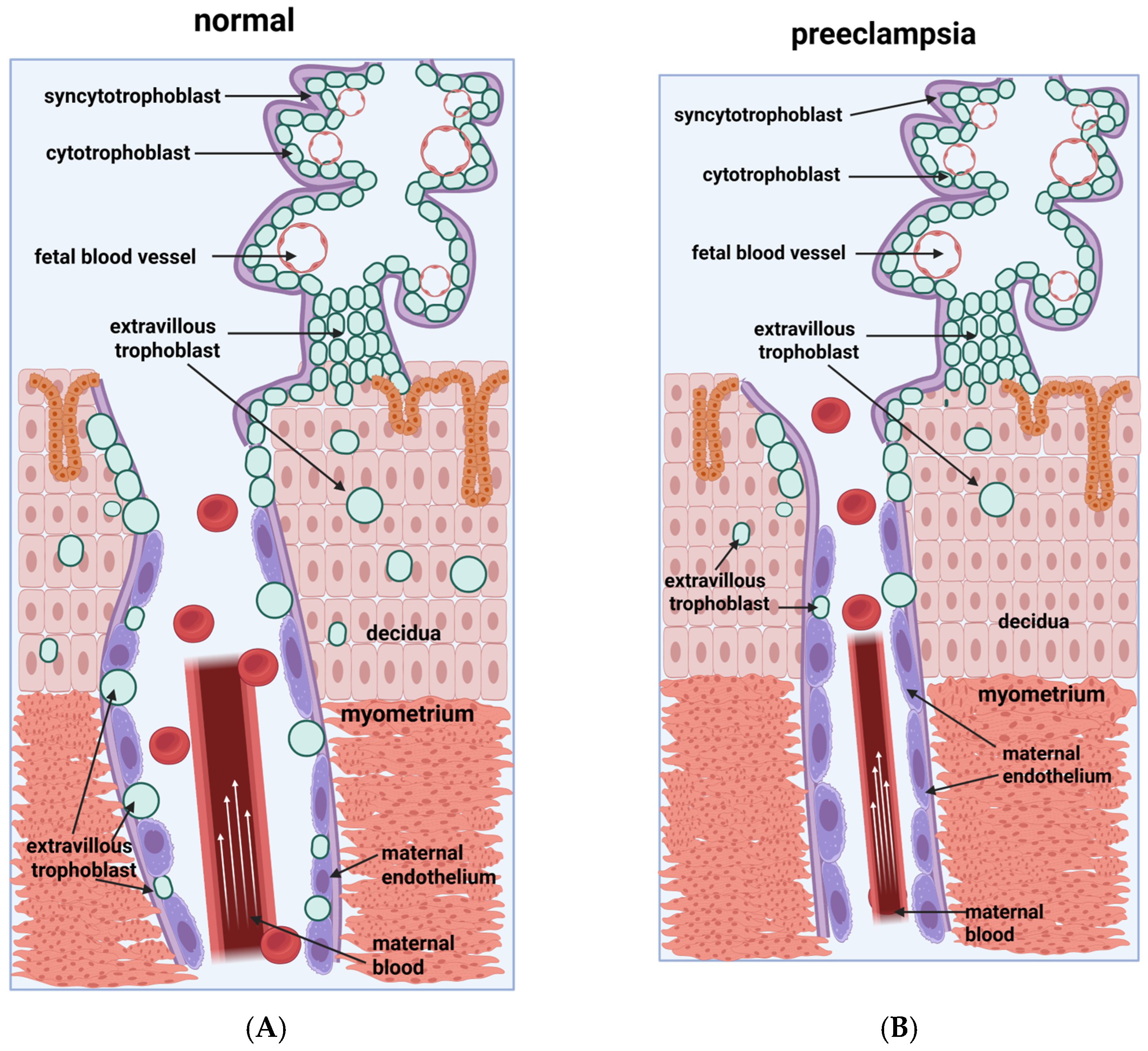

3. Pathophysiology of the Placenta

4. Molecular Approach to Placental Disorders

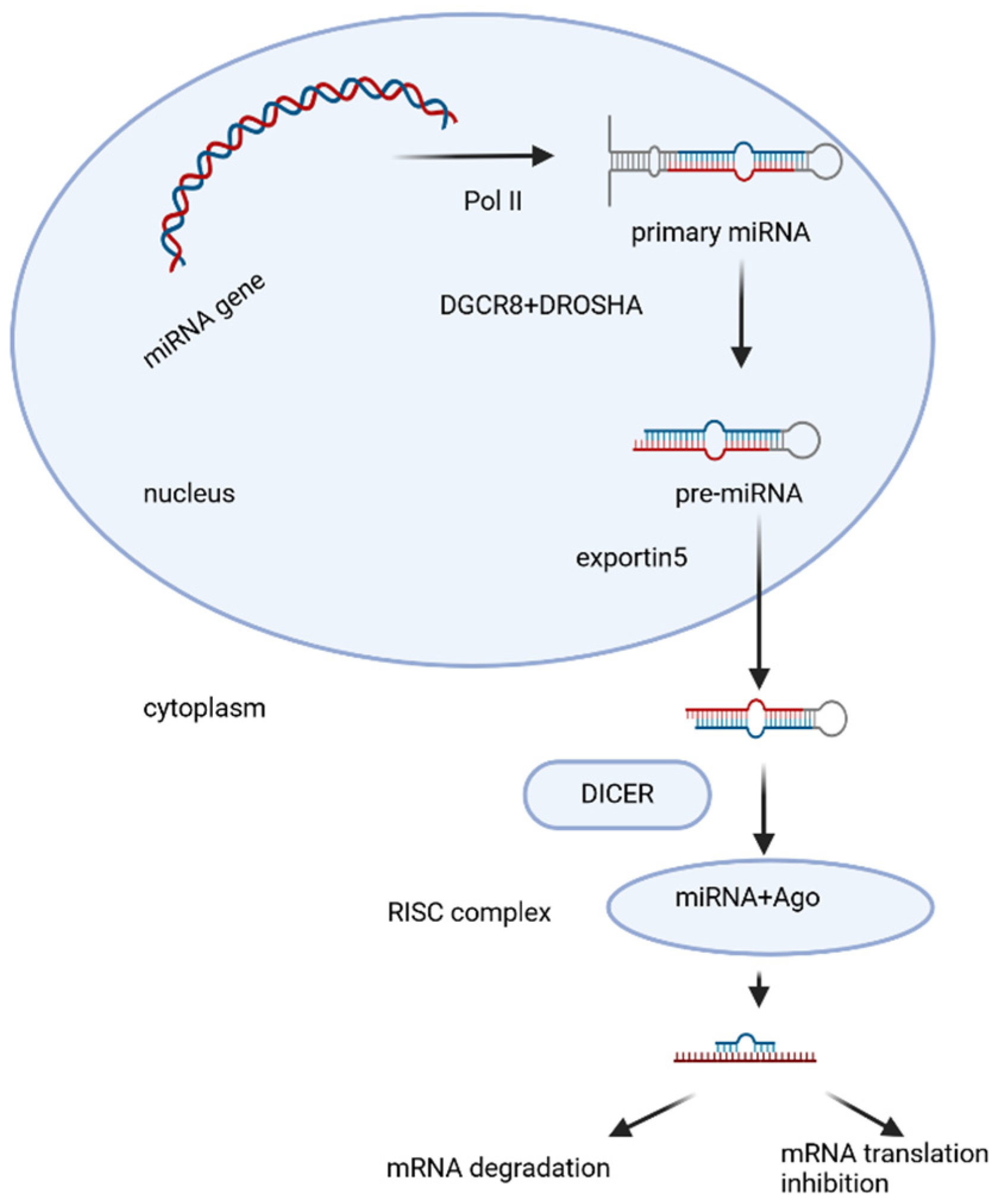

4.1. Biogenesis and Biological Function of miRNAs

4.2. Expression of miRNAs in Human Placenta

4.3. MicroRNAs and Human Gestational Disorders

4.4. Preeclampsia (PE) and miRNAs

| Downregulated miRNAs | Affected Biological Process |

|---|---|

| miR-378a-5p [116], miR-376c [117], miR-335 [118], miR-126 [119] | proliferation ↑ |

| miR-378a-5p [116], miR-3935 [113], miR-376c [117], miR-126 [119] | migration ↑ |

| miR-378a-5p [116], miR-3935 [113] | invasion ↑ |

| miR-335 [118], miR-125a [120] | apoptosis ↓ |

| miR-126 [119] | differentiation ↑ |

| miR-195 [121] | other/targets ↑ |

| miR-153-3p [110], miR-653-5p [110], miR-325 [110] | in exosomes |

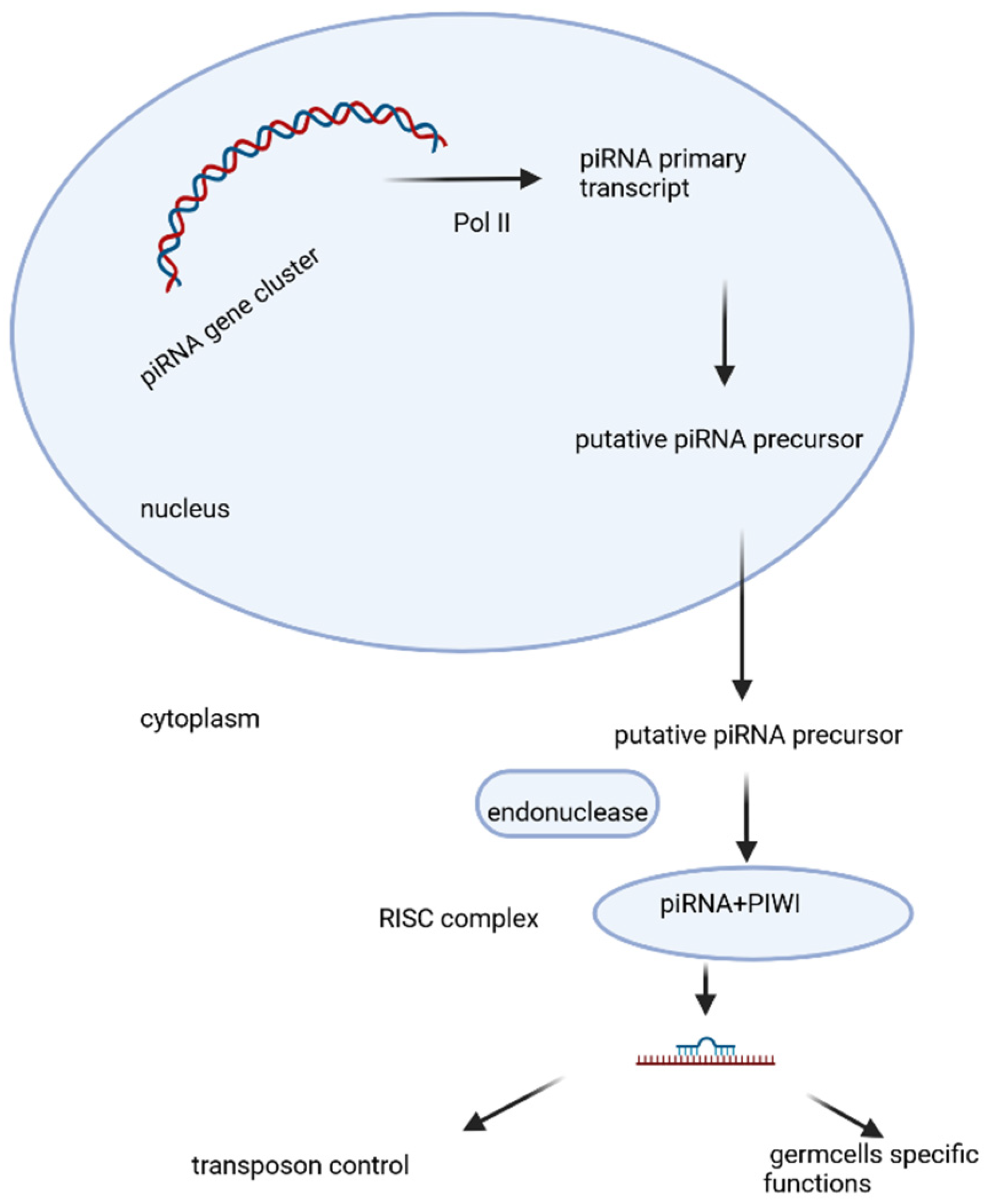

4.5. Preeclampsia and Piwi-Interacting RNAs (piRNAs)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available online: https://languages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/ (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Fitzgerald, J.S.; Poehlmann, T.G.; Schleussner, E.; Markert, U.R. Trophoblast invasion: The role of intracellular cytokine signalling via signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). Hum. Reprod. Update 2008, 14, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, O.W.; Wagner, G.P. The placenta as a model for understanding the origin and evolution of vertebrate organs. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 0072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, D.G.; Avanzati, A.M.; Paulesu, L. Classics revisited. History of reptile placentology: Studiati’s early account of placentation in a viviparous lizard. Placenta 2015, 36, 1207–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reznick, D.N.; Mateos, M.; Springer, M.S. Independent origins and rapid evolution of the placenta in the fish genus Poeciliopsis. Science 2002, 298, 1018–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.C.; Hsueh, Y.W.; Chang, C.W.; Hsu, H.C.; Yang, T.C.; Lin, W.C.; Chang, H.M. Establishment of the fetal-maternal interface: Developmental events in human implantation and placentation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1200330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vcelkova, T.; Latos, P.A. Cis-regulatory elements operating in the trophoblast. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1661952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Xu, Q.; Li, J.; Xu, S.; Tang, C. Micro-RNAs in human placenta: Tiny molecules, immense power. Molecules 2022, 27, 5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaglia, E.; Montella, F.; Lopardo, V.; Basile, C.; Esposito, R.M.; Maglio, C.; Longo, R.; Maciag, A.; Puca, A.A. The Genetic and Epigenetic Arms of Human Ageing and Longevity. Biology 2025, 14, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Human Proteome in Placenta—The Human Protein Atlas. www.proteinatlas.org. Available online: https://www.proteinatlas.org/humanproteome/tissue/placenta (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Ramsey, E.M.; Donner, M.W. Placental vasculature and circulation in primates: A review. In Placental Vascularization and Blood Flow: Basic Research and Clinical Applications; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1988; pp. 217–233. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, G.J.; Charnock-Jones, D.S.; Jauniaux, E. Regulation of vascular growth and function in the human placenta. Reproduction 2009, 138, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, G.; Huppertz, B. Implantation and extravillous trophoblast invasion: From rare archival specimens to modern biobanking. Placenta 2017, 56, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, G.; Windsperger, K.; Pollheimer, J.; de Sousa Lopes, S.C.; Huppertz, B. Human trophoblast invasion: New and unexpected routes and functions. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 150, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, G.; Weiss, G.; Gauster, M.; Sundl, M.; Huppertz, B. Evidence from the very beginning: Endoglandular trophoblasts penetrate and replace uterine glands in situ and in vitro. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 2747–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, K.M.; Elad, D. Biomechanics of the human uterus. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2017, 9, e1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; He, J.H.; Hu, L.L.; Jiang, L.L.; Fang, L.; Yao, G.D.; Liu, L.; Shang, T.; Sato, Y.; Kawamura, K.; et al. Placensin is a glucogenic hormone secreted by human placenta. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e49530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsperger, K.; Dekan, S.; Pils, S.; Golletz, C.; Kunihs, V.; Fiala, C.; Kristiansen, G.; Knöfler, M.; Pollheimer, J. Extravillous trophoblast invasion of venous as well as lymphatic vessels is altered in idiopathic, recurrent, spontaneous abortions. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitby, S.; Zhou, W.; Dimitriadis, E. Alterations in epithelial cell polarity during endometrial receptivity: A systematic review. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 596324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.J. Cell polarity: Models and mechanisms from yeast, worms and flies. Development 2013, 140, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.Y.; Murphy, C.R. Cytoskeletal proteins in uterine epithelial cells only partially return to the pre-receptive state after the period of receptivity. Acta Histochem. 2002, 104, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dashe, J.S.; Bloom, S.L.; Spong, C.Y.; Hoffman, B.L. Williams Obstetrics; McGraw Hill Professional: Houston, TX, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-259-64433-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kiserud, T.; Acharya, G. The fetal circulation. Prenat. Diagn. 2004, 24, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusoodanan, J. Break on through: How some viruses infect the placenta. Knowable Magazine, 10 October 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L. Congenital Viral Infection: Traversing the Uterine-Placental Interface. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2018, 5, 273–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeira, P.; Quinello, C.; Silveira-Lessa, A.L.; Zago, C.A.; Carneiro-Sampaio, M. IgG placental transfer in healthy and pathological pregnancies. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 2012, 985646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillitteri, A. Maternal and Child Health Nursing: Care of the Childbearing and Childrearing Family; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Hagerstwon, MD, USA, 2009; p. 202. ISBN 978-1-58255-999-5. [Google Scholar]

- White, B.; Harrison, J.R.; Lisa Mehlmann, L. Endocrine and Reproductive Physiology, 5th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9780323595735. [Google Scholar]

- Handwerger, S.; Freemark, M. The roles of placental growth hormone and placental lactogen in the regulation of human fetal growth and development. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 13, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B. Immunology of Animal Reproduction; Chapter; Placental mechanisms; Scientific e-Resources; ED-Tech Press: Essex, UK, 2018; pp. 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Aluvihare, V.R.; Kallikourdis, M.; Betz, A.G. Regulatory T cells mediate maternal tolerance to the fetus. Nat. Immunol. 2004, 5, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, M.; Bell, D.W.; Haber, D.A.; Li, E. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell 1999, 99, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappen, C.; Kruger, C.; MacGowan, J.; Salbaum, J.M. Maternal diet modulates placenta growth and gene expression in a mouse model of diabetic pregnancy. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, E38445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, N.; Leidinger, P.; Becker, K.; Backes, C.; Fehlmann, T.; Pallasch, C.; Rheinheimer, S.; Meder, B.; Stähler, C.; Meese, E.; et al. Distribution of miRNA expression across human tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 3865–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatti, G.K.; Khullar, N.; Sidhu, I.S.; Navik, U.S.; Reddy, A.P.; Reddy, P.H.; Bhatti, J.S. Emerging role of non-coding RNA in health and disease. Metab. Brain Dis. 2021, 36, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C.; Feinbaum, R.L.; Ambros, V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs that are antisense complementary to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasello, L.; Distefano, R.; Nigita, G.; Croce, C.M. The MicroRNA family gets wider: The IsomiRs classification and role. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 668648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloonan, N.; Wani, S.; Xu, Q.; Gu, J.; Lea, K.; Heater, S.; Barbacioru, C.; Steptoe, A.L.; Martin, H.C.; Nourbakhsh, E.; et al. MicroRNAs and their isomiRs function cooperatively to target common biological pathways. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, M.; Han, J.; Yeom, K.H.; Lee, S.; Baek, S.H.; Kim, V.N. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, V.; Sengar, R.S. Biogenesis and mechanisms of microRNA-mediated gene regulation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2022, 119, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denli, A.M.; Tops, B.B.; Plasterk, R.H.; Ketting, R.F.; Hannon, G.J. Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex. Nature 2004, 432, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Jeon, K.; Lee, J.T.; Kim, S.; Kim, V.N. MicroRNA maturation: Stepwise processing and subcellular localization. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 4663–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.R.; Cullen, B.R. Recognition and cleavage of primary microRNA precursors by the nuclear processing enzyme Drosha. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.; Kim, V. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, E.; Caudy, A.A.; Hammond, S.M.; Hannon, G.J. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature 2001, 409, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grishok, A.; Pasquinelli, A.E.; Conte, D.; Li, N.; Parrish, S.; Ha, I.; Baillie, D.L.; Fire, A.; Ruvkun, G.; Mello, C.C. Genes and mechanisms related to RNA interference regulate expression of the small temporal RNAs that control C. elegans developmental timing. Cell 2001, 106, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutvagner, G.; McLachlan, J.; Pasquinelli, A.E.; Bálint, É.; Tuschl, T.; Zamore, P.D. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science 2001, 293, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.S.; Rossi, J.J. Molecular mechanisms of Dicer: Endonuclease and enzymatic activity. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1603–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, I.J.; Doudna, J.A. Ribonuclease revisited: Structural insights into ribonuclease III family enzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007, 17, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipowicz, W. RNAi: The nuts and bolts of the RISC machine. Cell 2005, 122, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontheimer, E.J. Assembly and function of RNA silencing complexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khvorova, A.; Reynolds, A.; Jayasena, S.D. Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell 2003, 115, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, D.S.; Zamore, P.D. Why do miRNAs live in the miRNP? Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vashukova, E.S.; Glotov, A.S.; Fedotov, P.V.; Efimova, O.A.; Pakin, V.S.; Mozgovaya, E.V.; Pendina, A.A.; Tikhonov, A.V.; Koltsova, A.S.; Baranov, V.S. Placental microRNA expression in pregnancies complicated by superimposed preeclampsia on chronic hypertension. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, G.J.; Cindrova-Davies, T.; Yung, H.W.; Jauniaux, E. Hypoxia and Reproductive Health: Oxygen and development of the human placenta. Reproduction 2021, 161, F53–F65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszczuk, I.; Koczkodaj, D.; Kondracka, A.; Kwasniewska, A.; Winkler, I.; Filip, A. The role of miRNA-210 in pre-eclampsia development. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, F.; Cen, H.; Shi, L. Hypoxia-induced microRNA-141 regulates trophoblast apoptosis, invasion, and vascularization by blocking CXCL12beta/CXCR2/4 signal transduction. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 116, 108836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, M.; Du, H.; Han, B.; Xia, G.; Shi, X.; Zhang, F.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, T. Hypoxia-inducible microRNA-218 inhibits trophoblast invasion by targeting LASP1: Implications for preeclampsia development. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2017, 87, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, E1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Mansur, A.; Adir, M.; Nahum, R.; Hauser, R.; Bollati, V.; Racowsky, C.; Machtinger, R. Maternal Phthalate and Personal Care Products Exposure Alters Extracellular Placental miRNA Profile in Twin Pregnancies. Reprod. Sci. 2019, 26, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRocca, J.; Binder, A.M.; McElrath, T.F.; Michels, K.B. First-Trimester Urine Concentrations of Phthalate Metabolites and Phenols and Placenta miRNA Expression in a Cohort of U.S. Women. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dong, S. Emerging roles of long non-coding RNAs in the toxicology of environmental chemicals. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2018, 38, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X. The roles of microRNAs in epigenetic regulation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 51, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguer-Dance, M.; Abu-Amero, S.; Al-Khtib, M.; Lefevre, A.; Coullin, P.; Moore, G.E.; Cavaille, J. The primate-specific microRNA gene cluster (C19MC) is imprinted in the placenta. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 3566–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prats-Puig, A.; Xargay-Torrent, S.; Carreras-Badosa, G.; Mas-Pares, B.; Bassols, J.; Petry, C.J.; Girardot, M.; Francis, D.E.Z.; Ibanez, L.; Dunger, D.B.; et al. Methylation of the C19MC microRNA locus in the placenta: Association with maternal and chilhood body size. Int. J. Obes. 2020, 44, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhnia, F.; Aplin, J.D.; Westwood, M. Dicer-dependent miRNAs provide an endogenous restraint on cytotrophoblast proliferation. Placenta 2012, 33, 581–585. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, G.; Ye, G.; Nadeem, L.; Ji, L.; Manchanda, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qiao, J.; Wang, Y.L.; Lye, S.; et al. MicroRNA-376c impairs transforming growth factor-beta and nodal signaling to promote trophoblast cell proliferation and invasion. Hypertension 2013, 61, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huang, X.; He, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Fang, Q. miRNA-210-3p regulates trophoblast proliferation and invasiveness through fibroblast growth factor 1 in selective intrauterine growth restriction. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 4422–4433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. MiR-133b regulates oxidative stress injury of trophoblasts in preeclampsia by mediating the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. J. Mol. Histol. 2021, 52, 1177–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Diao, Z.; Shen, L.; Xue, P.; Sun, H.; Hu, Y. MicroRNA-155 inhibits proliferation and migration of human extravillous trophoblast derived HTR-8/SVneo cells via down-regulating cyclin D1. Placenta 2012, 33, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; He, Z.; Cai, J.; Huang, L.; Zhu, H.; Luo, Y. Potential role of microRNA-424 in regulating ERRgamma to suppress trophoblast proliferation and invasion in fetal growth restriction. Placenta 2019, 83, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, M.Q.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.P.; Jin, L.P. MicroRNA-184 promotes apoptosis of trophoblast cells via targeting WIG1 and induces early spontaneous abortion. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, K.; Matsubara, Y.; Uchikura, Y.; Takagi, K.; Yano, A.; Sugiyama, T. HMGA1 Is a Potential Driver of Preeclampsia Pathogenesis by Interference with Extravillous Trophoblasts Invasion. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, A.; Shima, T.; Aoki, A.; Kawaguchi, M.; Yasuda, I.; Tsuda, S.; Yoneda, S.; Yamaki-Ushijima, A.; Cheng, S.B.; Sharma, S.; et al. Molecular and immunological developments in placentas. Hum. Immunol. 2021, 82, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Fang, X.; Shao, T.; Shao, X.; Wang, Y.-L. Placental Steroid Hormones in Preeclampsia: Multilayered Regulation of Endocrine Pathogenesis. Endocr. Rev. 2025, bnaf039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Chen, H.; Liu, J.; Tong, C.; Meng, T. MicroRNA-34a inhibits human trophoblast cell invasion by targeting MYC. BMC Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Chen, A.; Yang, H.; Hong, L. MicroRNA-27a inhibits trophoblast cell migration and invasion by targeting SMAD2: Potential role in preeclampsia. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 2262–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Deng, M.; Wang, Q. MiRNA-320a inhibits trophoblast cell invasion by targeting estrogen-related receptor-gamma. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2018, 44, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkara, A.; Kaya, A.E.; Başbuğ, A.; Ökten, S.B.; Doğan, O.; Çağlar, M.; Kumru, S. Proteinuria in preeclampsia: Is it important? Ginekol. Pol. 2018, 89, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaly, Z.; Jadaon, J.E.; Jabbour, A.; Abassi, Z.A. Preeclampsia: Novel Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Approaches. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.W.; Sinkey, R.; Rajapreyar, I.; Tita, A.T.N.; Oparil, S. Preeclampsia-pathophysiology and clinical presentations: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1690–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.A.; Bejjani, L.; Francisco, R.P.V.; Patino, E.G.; Vivanti, A.; Batista, F.S.; Zugaib, M.; Mercier, F.J.; Bernardes, L.S.; Benachi, A. Outcomes following medical termination versus prolonged pregnancy in women with severe preeclampsia before 26 weeks. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.L.; Zhang, H.Z.; Meng, F.R.; Han, S.Y.; Zhang, M. Differential expression of microRNA-411 and 376c is associated with hypertension in pregnancy. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2019, 52, e7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayder, H.; O’Brien, J.; Nadeem, U.; Peng, C. MicroRNAs: Crucial regulators of placental development. Reproduction 2018, 155, R259–R271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman-Wohl, D.; Yagel, S. Regulation of trophoblast invasion: From normal implantation to pre-eclampsia. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2002, 187, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavov, I. Late Gestational Toxicoses; Medicina I Fizcultura Publishing House: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1980; pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Feng, L.; Zhang, H.; Hachy, S.; Satohisa, S.; Laurent, L.C.; Parast, M.; Zheng, J.; Chen, D.B. Preeclampsia up-regulates angiogenesis-associated microRNA (i.e., miR-17, -20a, and -20b) that target ephrin-B2 and EPHB4 in human placenta. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, E1051–E1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Meng, T. MicroRNA-431 affects trophoblast migration and invasion by targeting ZEB1 in preeclampsia. Gene 2019, 683, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Yu, X.; Gong, W. MiR-30a-3p targeting FLT1 modulates trophoblast cell proliferation in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Horm. Metab. Res. 2022, 54, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.R.; Han, T.; Sun, X.L.; Luan, L.X.; Gou, W.L.; Zhu, X.M. MicroRNA-30a-3p is overexpressed in the placentas of patients with preeclampsia and affects trophoblast invasion and apoptosis by its effects on IGF-1. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 249.e1–249.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Li, H.; Xu, H.; Huo, G.; Yao, Y. MicroRNA-20b inhibits trophoblast cell migration and invasion by targeting MMP-2. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2017, 10, 10901–10909. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Ji, Q.; Dong, L.; Meng, Y.; Xin, G. HDAC4 Knockdown Induces Preeclampsia Cell Autophagy and Apoptosis by miR-29b. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 28, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Lian, F.; Cai, Y. Ligustrazine-induced microRNA-16-5p inhibition alleviates preeclampsia through IGF-2. Reproduction 2020, 160, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beards, F.; Jones, L.E.; Charnock, J.; Forbes, K.; Harris, L.K. Placental Homing Peptide-microRNA Inhibitor Conjugates for Targeted Enhancement of Intrinsic Placental Growth Signaling. Theranostics 2017, 7, 2940–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina-Prieto, S.; Chaiwangyen, W.; Herrmann, J.; Groten, T.; Schleussner, E.; Markert, U.R.; Morales-Prieto, D.M. MicroRNA-141 is upregulated in preeclamptic placentae and regulates trophoblast invasion and intercellular communication. Transl. Res. 2016, 172, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Hou, B.; Shan, L.; Sun, X.; Wang, L. Aberrantly up-regulated miR-142-3p inhibited the proliferation and invasion of trophoblast cells by regulating FOXM1. Placenta 2021, 104, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Wang, D.; Lu, J.; Zhou, X. MiR-125b participates in the occurrence of preeclampsia by regulating the migration and invasion of extravillous trophoblastic cells through STAT3 signaling pathway. J. Recept. Signal. Transduct. Res. 2021, 41, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin-Beidokhti, M.; Sadeghi, H.; Pirjani, R.; Gachkar, L.; Gholami, M.; Mirfakhraie, R. Differential expression of Hsa-miR-517a/b in placental tissue may contribute to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2021, 22, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, R.M.A.; Saeidi, K.; Gharbi, S.; Salari, Z.; Saleh-Gohari, N. Quantification of circulating miR-517c-3p and miR-210-3p levels in preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2019, 16, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, L.; Olarerin-George, A.O.; Hogenesch, J.B.; Elovitz, M.A. Placental expression of miR-517a/b and miR-517c contributes to trophoblast dysfunction and preeclampsia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, X. MiR-200b-3p is upregulated in the placental tissues from patients with preeclampsia and promotes the development of preeclampsia via targeting profilin 2. Cell Cycle 2022, 21, 1945–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.M.; Lu, W.; Zhao, L.J. MicroRNA-137 Affects Proliferation and Migration of Placenta Trophoblast Cells in Preeclampsia by Targeting ERRalpha. Reprod. Sci. 2017, 24, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizyaeva, N.V.; Kulikova, G.V.; Nagovitsyna, M.N.; Kan, N.E.; Prozorovskaya, K.N.; Shchegolev, A.I.; Sukhikh, G.T. Expression of MicroRNA-146a and MicroRNA-155 in Placental Villi in Early- and Late-Onset Preeclampsia. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 163, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Z.; Luo, S. Aberrantly up-regulated miR-20a in pre-eclampsic placenta compromised the proliferative and invasive behaviors of trophoblast cells by targeting forkhead box protein A1. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2014, 10, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Luo, Y.; Tudela, C.; Alexander, J.M.; Mendelson, C.R. The c-Myc-regulated microRNA-17~92 (miR-17~92) and miR 106a~363 clusters target hCYP19A1 and hGCM1 to inhibit human trophoblast differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013, 33, 1782–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akehurst, C.; Small, H.Y.; Sharafetdinova, L.; Forrest, R.; Beattie, W.; Brown, C.E.; Robinson, S.W.; McClure, J.D.; Work, L.M.; Carty, D.M.; et al. Differential expression of microRNA-206 and its target genes in preeclampsia. J. Hypertens. 2015, 33, 2068–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Muralimanoharan, S.; Maloyan, A.; Mele, J.; Guo, C.; Myatt, L.G.; Myatt, L. MIR-210 modulates mitochondrial respiration in placenta with preeclampsia. Placenta 2012, 33, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Williams, J., III; Brown, J.; Wang, E.T.; Lee, B.; Gonzalez, T.L.; Cui, J.; Goodarzi, M.O.; Pisarska, M.D. Up-regulation of microRNA-202-3p in first trimester placenta of pregnancies destined to develop severe preeclampsia, a pilot study. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2017, 10, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Diao, Z.; Yany, M.; Wu, M.; Sun, H.; Yan, G.; Hu, Y. Placenta associated serum exosomal miR155 derived from patients with preeclampsia inhibits eNOS expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Ouyang, Y.; Sadovsky, E.; Parks, W.T.; Chu, T.; Sadovsky, Y. Unique microRNA Signals in Plasma Exosomes from Pregnancies Complicated by Preeclampsia. Hypertension 2020, 75, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, C.; Guanzon, D.; Scholz-Romero, K.; Longo, S.; Correa, P.; Illanes, S.E.; Rice, G.E. Placental Exosomes as Early Biomarker of Preeclampsia: Potential Role of Exosomal MicroRNAs Across Gestation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 3182–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motawi, T.M.K.; Sabry, D.; Maurice, N.W.; Rizk, S.M. Role of mesenchymal stem cells exosomes derived microRNAs; miR-136, miR-494 and miR-495 in pre-eclampsia diagnosis and evaluation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 659, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Xu, S.; Li, J.; Yao, Y.; Tang, C. MicroRNA-3935 promotes human trophoblast cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition through tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6/regulator of G protein signaling 2 axis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2021, 19, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokni, M.; Salimi, S.; Sohrabi, T.; Asghari, S.; Teimoori, B.; Saravani, M. Association between miRNA-152 polymorphism and risk of preeclampsia susceptibility. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 299, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, P.; Song, H.; Xie, C.; Zheng, W.; Ma, H.; Xin, D.; Zhan, J.; Yuan, X.; Chen, A.; Tao, J.; et al. miR-146a-5p-mediated suppression on trophoblast cell progression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in preeclampsia. Biol. Res. 2021, 54, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Ye, G.; Nadeem, L.; Fu, G.; Yang, B.B.; Honarparvar, E.; Dunk, C.; Lye, S.; Peng, C. MicroRNA-378a-5p promotes trophoblast cell survival, migration, and invasion by targeting Nodal. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 3124–3132. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, A.H.; Delles, C. Is microRNA-376c a biomarker or mediator of preeclampsia? Hypertension 2013, 61, 767–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Jiang, L.; Li, M.; Gan, H.; Yang, L.; Lin, F.; Hu, M. miR-335 targets CRIM1 to promote the proliferation and inhibit the apoptosis of placental trophoblast cells in preeclamptic rats. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 4676–4685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yan, T.; Liu, Y.; Cui, K.; Hu, B.; Wang, F.; Zou, L. MicroRNA-126 regulates EPCs function: Implications for a role of miR-126 in preeclampsia. J. Cell. Biochem. 2013, 114, 2148–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Meng, J.; Zuo, C.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Zhao, S.; Huang, T.; Wang, X.; Yan, J. Downregulation of MicroRNA-125a in Placenta Accreta Spectrum Disorders Contributes Antiapoptosis of Implantation Site Intermediate Trophoblasts by Targeting MCLI. Reprod. Sci. 2019, 26, 1582–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrim, V.C.; Eleuterio, N.; Pilan, E.; Tanus-Santos, J.E.; Fernandes, K.; Cavalli, R. Plasma levels of increased miR-195-5p correlate with the sFLT-1 levels in preeclampsia. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2016, 35, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yu, X.; Zhang, S.; He, Y.; Guo, W. Novel roles of PIWI proteins and PIWI-interacting RNAs in human health and diseases. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litwack, G. Chapter: Nucleic Acids and Molecular Genetics. In Human Biochemistry; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 309–310. [Google Scholar]

- Delpu, Y.; Larrieu, D.; Gayral, M.; Arvanitis, D.; Dufresne, M.; Cordelier, P.; Torrisani, J. Noncoding RNAs: Clinical and therapeutic applications. In Drug Discovery in Cancer Epigenetics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 305–326. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Wang, T.; Gao, X.Q.; Chen, X.Z.; Wang, F.; Zhou, L.Y. Emerging functions of piwi-interacting RNAs in diseases. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 4893–4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, M.; Xu, J.; Fang, J.; Liu, Z.; Qi, H. Identification and characterization of Piwi-interacting RNAs in human placentas of preeclampsia. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 15766, Erratum in Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 18652. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98274-4. PMID: 34344990; PMCID: PMC8333249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Miller, D.C.; Harman, R.; Antczak, D.F.; Clark, A.G. Paternally expressed genes predominate in the placenta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 10705–10710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, K.F.; Pezic, D.; Stuwe, E.; Webster, A. The piRNA pathway guards the germline genome against transposable elements. In Non-Coding RNA and the Reproductive System; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hasuwa, H.; Ishino, K.; Siomi, H. Human PIWI (HIWI) is an azoospermia factor. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 61, 348–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hou, B.; Zong, J.; Liu, S. Potential molecular mechanisms and clinical implications of piRNAs in preeclampsia: A review. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2024, 22, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Upregulated miRNAs | Affected Biological Process |

|---|---|

| miR-155 [70] miR-20a [96], miR-16-5p [93], miR-142-3p [96], miR-200p-3b [101], miR-137 [102], miR-146a [103] | proliferation ↓ |

| miR-155 [70], miR-431 [88], miR-20b [91], miR-16-5p [93], miR-125b [97], miR-200p-3b [102], miR-137 [102], miR-146a [103] | migration ↓ |

| miR-431 [88], miR-30a-3p [90], miR-20a [104], miR-20b [91], miR-141 [95], miR-142-3p [96], miR-125b [97], miR-146a [103], miR-517a/b [100], miR-517c [100] | invasion ↓ |

| miR-30a-3p [90], miR-29b [92], miR-16-5p [93], miR-200p-3b [101] | apoptosis ↑ |

| miR-17-~92 clusters [105], miR-106a~363 clusters [105] | differentiation ↓ |

| miR17 [87], miR-206 [106], miR-210 [107], miR-202-3p [108], miR-155 [109] | other/targets ↓ |

| miR-222-3p [110], miR-486-1-5p [111], miR-486-2-5p [111], miR-155 [109], miR-136 [112], miR-494 [112], miR-495 [112] | in exosomes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Milova, N.; Nikolova, M.; Yordanov, A.; Milov, A.; Mandadzhieva, S. Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed… About the Placenta. Epigenomes 2026, 10, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/epigenomes10010005

Milova N, Nikolova M, Yordanov A, Milov A, Mandadzhieva S. Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed… About the Placenta. Epigenomes. 2026; 10(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/epigenomes10010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilova, Nadezhda, Maria Nikolova, Angel Yordanov, Antoan Milov, and Stoilka Mandadzhieva. 2026. "Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed… About the Placenta" Epigenomes 10, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/epigenomes10010005

APA StyleMilova, N., Nikolova, M., Yordanov, A., Milov, A., & Mandadzhieva, S. (2026). Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed… About the Placenta. Epigenomes, 10(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/epigenomes10010005