An Evaluation of the Popularity of Australian Native Bee Taxa and State of Knowledge of Native Bee Taxonomy Among the Bee-Interested Public

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Evaluate bee taxonomic literacy among Australian citizens who were interested in bees;

- Identify which Australian bee species emerged as the favourite(s) among the public, which can therefore be used as a gateway and/or flagship species;

- Identify which bee taxa were under-represented and therefore require more outreach and science education.

2. Methods and Materials

3. Results

4. Discussion

- (a)

- At least in terms of the stated favourite bee species, there were gaps in taxonomic knowledge, in terms of scientific nomenclature, taxonomic rank in relation to the question of favourite species, and over-representation of certain taxa.

- (b)

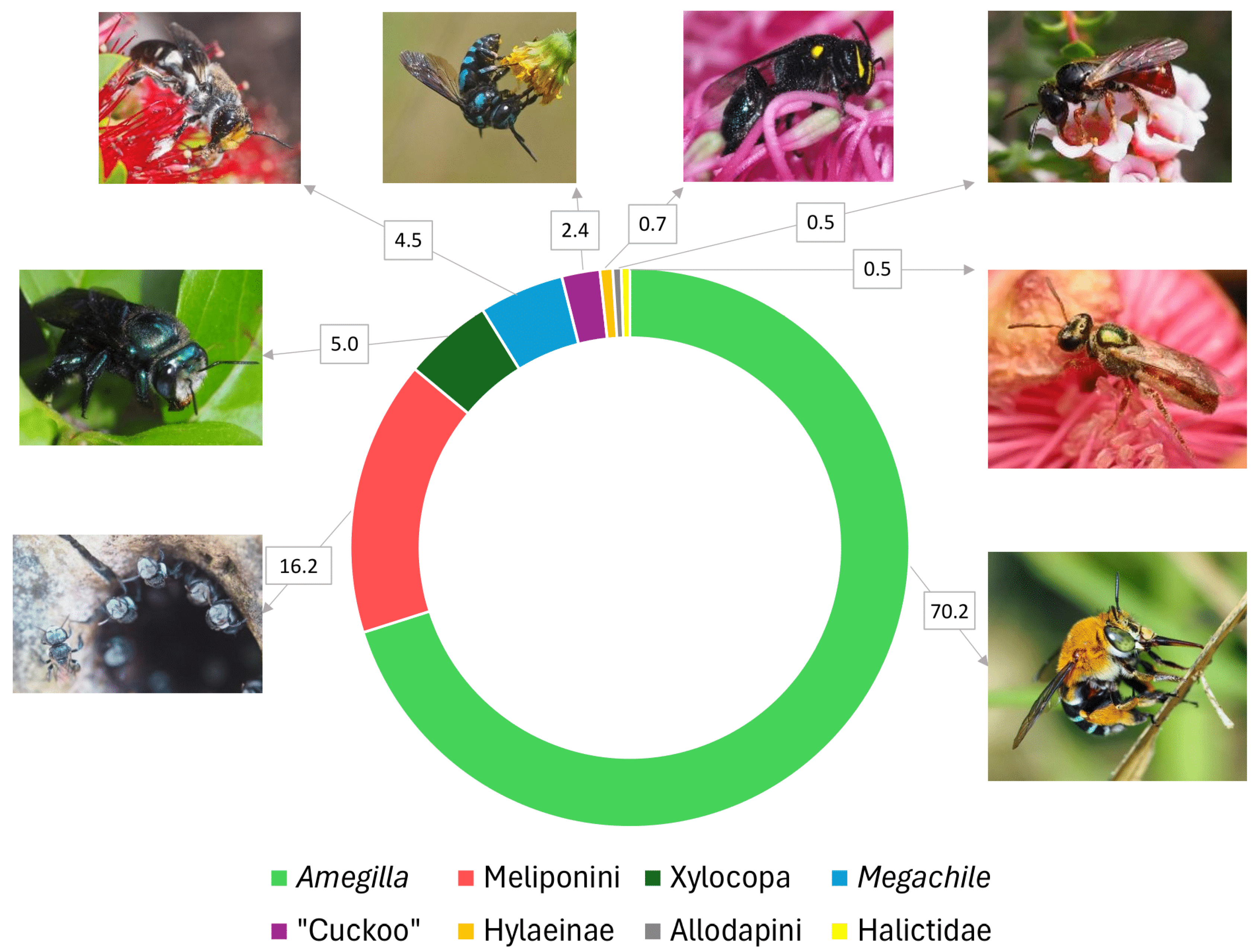

- “Blue banded” Amegilla and Tetragonula carbonaria, were the most popular taxa among bee-interested Australian citizens. Amegilla, in particular those in the subgenera Zonamegilla and Notomegilla, emerged as popular native Australian bees among the public, and are good candidates for flagships.

- (c)

- Colletids and Stenotritids were extremely under-represented and therefore require more outreach and science education. This is especially concerning since, unlike the other families and genera, these taxa are endemic to Australia.

4.1. Poor Taxonomic Knowledge

4.2. Why Do the Public Love “Blue Banded Bees” so Much?

4.3. Popularity of Meliponini, Especially Tetragonula carbonaria and T. hockingsi

4.4. Popularity of Megachilids and Xylocopa

4.5. Amegilla as a Gateway, but Not a Flagship

4.6. Selecting a Flagship

4.7. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hall, D.M.; Martins, D.J. Human dimensions of insect pollinator conservation. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2020, 38, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulson, D. The insect apocalypse, and why it matters. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R967–R971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drossart, M.; Gérard, M. Beyond the decline of wild bees: Optimizing conservation measures and bringing together the actors. Insects 2020, 11, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ, L.; Dreesmann, D.C. SAD but True: Species Awareness Disparity in Bees Is a Result of Bee-Less Biology Lessons in Germany. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldmann, J.; González-Varo, J.P. Conserving honey bees does not help wildlife. Science 2018, 359, 392–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, K.S.; Ollerton, J. Impacts of the introduced European honeybee on Australian bee-flower network properties in urban bushland remnants and residential gardens. Austral Ecol. 2022, 47, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, K.S.; Dixon, K.W.; Bateman, P.W. The evidence for and against competition between the European honeybee and Australian native bees. Pac. Conserv. Biol. 2022, 29, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, K.; Murphy, M.V.; Kevan, P.G.; Ren, Z.-X.; Milne, L.A. Introduced honey bees (Apis mellifera) potentially reduce fitness of cavity-nesting native bees through a male-bias sex ratio, brood mortality and reduced reproduction. Front. Bee Sci. 2025, 3, 1508958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, J.M.; Hogendoorn, K. How protection of honey bees can help and hinder bee conservation. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2021, 46, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, W.F.; Smagghe, G.; Guedes, R.N.C. Pesticides and reduced-risk insecticides, native bees and pantropical stingless bees: Pitfalls and perspectives. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015, 71, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naskrecki, P. Endangered Terrestrial Invertebrates. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity (Second Edition); Levin, S.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.S.; Forister, M.L.; Carril, O.M. Interest exceeds understanding in public support of bee conservation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 15, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Fauna Directory. Australian Fauna Directory. Available online: https://biodiversity.org.au/afd/taxa/APIFORMES (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Batley, M.; Hogendoorn, K. Diversity and conservation status of native Australian bees. Apidologie 2009, 40, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxonomy Australia. Discovering and Documenting Australia’s Native Bees. Available online: https://www.taxonomyaustralia.org.au/discoverbees (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Leijs, R.; King, J.; Dorey, J.; Hogendoorn, K. The Australian Resin Pot Bees, Megachile (Austrochile) (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae), with descriptions of 71 new species. Aust. J. Taxon. 2025, 90, 1–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIvor, J.S. Wild Bees in Cultivated City Gardens. In Sowing Seeds in the City: Ecosystem and Municipal Services; Brown, S., McIvor, K., Hodges Snyder, E., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 207–227. [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum, M. Insect conservation and the entomological society of America. Am. Entomol. 2008, 54, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greyvenstein, B.; du Plessis, H.; van den Berg, J. The charismatic praying mantid: A gateway for insect conservation. Afr. Zool. 2020, 55, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitsch, J.; Chuang, A.; Nelsen, D.R.; Sitvarin, M.; Coyle, D. Quantifying how natural history traits contribute to bias in community science engagement: A case study using orbweaver spiders. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 2024, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D. Flagships, umbrellas, and keystones: Is single-species management passé in the landscape era? Biol. Conserv. 1998, 83, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.S.; Braby, M.F.; Moir, M.L.; Harvey, M.S.; Sands, D.P.A.; New, T.R.; Kitching, R.L.; McQuillan, P.B.; Hogendoorn, K.; Glatz, R.V.; et al. Strategic national approach for improving the conservation management of insects and allied invertebrates in Australia. Austral Entomol. 2018, 57, 124–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberhauser, K.; Guiney, M. Insects as flagship conservation species. Terr. Arthropod Rev. 2009, 1, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberhauser, K.S.; Nail, K.R.; Altizer, S. Monarchs in a Changing World: Biology and Conservation of an Iconic Butterfly; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque, A.; Gagné, L.; Dupras, J. Expressing citizen preferences on endangered wildlife for building socially appealing species recovery policies: A stated preference experiment in Quebec, Canada. J. Nat. Conserv. 2022, 69, 126255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, A.; Osborne, W.; Robertson, G.; Hnatiuk, S. Community Monitoring of Golden Sun Moths in the Australian Capital Territory Region, 2008–2009; University of Canberra: Canberra, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pyke, G.H.; Prendergast, K.S.; Ren, Z.X. Pollination crisis Down-Under: Has Australasia dodged the bullet? Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecken, N.J.; Prendergast, K.S.; Bossert, S.; Hung, K.-L.J.; Roberts, S.P.M.; Villagra, C.; Warrit, N.; Wilson, J.S.; Wood, T.J.; Orr, M.C. Five good reasons not to dismiss scientific binomial nomenclature in conservation, environmental education and citizen science: A case study with bees. Syst. Entomol. 2024, 49, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, T.F. A Guide to the Native Bees of Australia; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton South, VIC, Australia, 2018; p. 280. [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast, K.; Ollerton, J. Plant-pollinator networks in Australian urban bushland remnants are not structurally equivalent to those in residential gardens. Urban Ecosyst. 2021, 24, 973–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, K.S.; Tomlinson, S.; Dixon, K.W.; Bateman, P.W.; Menz, M.H.M. Urban native vegetation remnants support more diverse native bee communities than residential gardens in Australia’s southwest biodiversity hotspot. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 265, 109408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Barton, P.S.; Cunningham, S.A. Flower visitation and land cover associations of above ground- and below ground-nesting native bees in an agricultural region of south-east Australia. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 295, 106895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas of Living Australia. Atlas of Living Australia. Available online: https://www.ala.org.au/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Prendergast, K.S. Native Bee Survey of Lake Claremont Nov 2019–Feb 2020; Lake Claremont: Claremont, WA, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, T.F. Observations on the nests and behaviour of some euryglossine bees (Hymenoptera: Colletidae). Aust. J. Entomol. 1969, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, T.F.; Prendergast, K.S. The tiny bee Euryglossina (Microdontura) mellea (Cockerell) (Hymenoptera: Colletidae, Euryglossinae) in Western Australia—introduced, or indigenous and long-overlooked? Aust. Entomol. 2022, 49, 287–295. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet, M.C. Framing science: A new paradigm in public engagement. In Communicating Science; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 54–81. [Google Scholar]

- Shreedhar, G. Evaluating the impact of storytelling in Facebook advertisements on wildlife conservation engagement: Lessons and challenges. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crew, B. The Neon Cuckoo Bee Is a Shiny Parasite. Available online: https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/blogs/creatura-blog/2015/03/neon-cuckoo-bee-a-shiny-parasite/ (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Hutchings, P.; Lavesque, N. I know who you are, but do others know? Why correct scientific names are so important for the biological sciences. Zoosymposia 2020, 19, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, R.A.; Jepson, P.; Malhado, A.C.; Ladle, R.J. Internet scientific name frequency as an indicator of cultural salience of biodiversity. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 78, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.-W.; Wang, W.-Z.; Wan, T.; Lee, P.-S.; Li, Z.-X.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Wilson, J.-J. Diversity and human perceptions of bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) in Southeast Asian megacities. Genome 2016, 59, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, M.; Acharya, S.K.; Chakraborty, S.K. Pollinators Unknown: People’s Perception of Native Bees in an Agrarian District of West Bengal, India, and Its Implication in Conservation. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2017, 10, 1940082917725440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daza, P.; Arista, M.; Berjano, R.; Ortiz, P.; Morón-Monge, H.; Antonini, Y. Bee pollination and bee decline: A study about university students’ Knowledge and its educational implication. BioScience 2024, 74, 851–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, M.M.; de Oliveira, J.S.; Fichberg, I.; Lellis-Santos, C. Addressing bee diversity through active learning methodologies enhances knowledge retention in an environmental education project. Interdiscip. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2024, 20, e2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijs, R.; Batley, M.; Hogendoorn, K. The genus Amegilla (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Anthophorini) in Australia: A revision of the subgenera Notomegilla and Zonamegilla. ZooKeys 2017, 653, 79–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prendegast, K. Nomia (Hoplonomia) rubroviridis Male. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/155520983@N07/54409708170/in/dateposted-public/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Vit, P.; Pedro, S.R.; Roubik, D. Pot-Honey: A Legacy of Stingless Bees; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Halcroft, M.T.; Spooner-Hart, R.; Haigh, A.M.; Heard, T.A.; Dollin, A. The Australian stingless bee industry: A follow-up survey, one decade on. J. Apic. Res. 2013, 52, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halcroft, M.; Spooner-Hart, R.; Dollin, L.A. Australian stingless bees. In Pot-Honey: A Legacy of Stingless Bees; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 35–72. [Google Scholar]

- Heard, T.A. The role of stingless bees in crop pollination. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1999, 44, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heard, T. The Australian Native Bee Book: Keeping Stingless Bee Hives for Pets, Pollination and Sugarbag Honey; Sugarbag Bees: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Klumpp, J. Australian Stingless Bees: A Guide to Sugarbag Beekeeping; Earthling Enterprises: West End, QLD, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Coonan, G. Keeping Australian Native Stingless Bees; Northern Bee Books: West Yorkshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Haley, D. The Honey of Australian Native Stingless Bees; Dean Haley: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast, K. Creating a Haven for Native Bees, 4th ed.; Dr Kit Prendergast, The Bee Babette: Caboolture South, QLD, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- MacIvor, J.S.; Packer, L. ‘Bee Hotels’ as Tools for Native Pollinator Conservation: A Premature Verdict? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrom, M. Bunnings, Big W, Aldi Slammed for Selling Garden “Death Traps”. Available online: https://au.sports.yahoo.com/bunnings-big-w-aldi-slammed-for-selling-garden-death-traps-013542101.html (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Sanders, P. Store-Bought bee hotels doing more harm than good for native species. ABC News, 20 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, R.A.; Jepson, P.R.; Malhado, A.C.; Ladle, R.J. Familiarity breeds content: Assessing bird species popularity with culturomics. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarić, I.; Correia, R.A.; Roberts, D.L.; Gessner, J.; Meinard, Y.; Courchamp, F. On the overlap between scientific and societal taxonomic attentions—Insights for conservation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenda, M.; Skórka, P.; Mazur, B.; Sutherland, W.; Tryjanowski, P.; Moroń, D.; Meijaard, E.; Possingham, H.P.; Wilson, K.A. Effects of amusing memes on concern for unappealing species. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 1200–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steen, Z.; Schwarz, M.P. Nesting and life cycle of the Australian green carpenter bees Xylocopa (Lestis) aeratus Smith and Xylocopa (Lestis) bombylans (Fabricius)(Hymenoptera: Apidae: Xylocopinae). Aust. J. Entomol. 2000, 39, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, R.; Leijs, R.; Hogendoorn, K. Biology, Distribution and Conservation of Green Carpenter Bee (Xylocopa aeratus: Apidae) on Kangaroo Island, South Australia; South Australia Museum: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hogendoorn, K.; Leijs, R.; Gatz, R. ‘Jewel of Nature’: Scientists Fight to Save a Glittering Green Bee After the Summer Fires. Available online: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/climate-change/green-carpenter-bee-jewel-of-nature-scientists-fight-to-save-green-carpenter-bee-xylocopa-aerata-after-the-summer-fires-72224 (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Kelly, M. Australia’s Green Carpenter Bee On The Brink. Xerces Blog 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hogendoorn, K.; Glatz, R.V.; Leijs, R. Conservation management of the green carpenter bee Xylocopa aerata (Hymenoptera: Apidae) through provision of artificial nesting substrate. Austral Entomol. 2021, 60, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogendoorn, K.; Leijs, R. Bee-log of The Green Carpenter Bee (Xylocopa aerata). Available online: https://thegreencarpenterbeexylocopaaerata.wordpress.com/bee-log-of-the-green-carpenter-bee-xylocopa-aerata/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Thiele, K. This Big Beautiful Bee Is in Serious Trouble. Available online: https://www.taxonomyaustralia.org.au/post/this-big-beautiful-bee-is-in-serious-trouble (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Barua, M.; Gurdak, D.J.; Ahmed, R.A.; Tamuly, J. Selecting flagships for invertebrate conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 1457–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danforth, B.N.; Minckley, R.L.; Neff, J.L. The Solitary Bees: Biology, Evolution, Conservation; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast, K.S. Beyond ecosystem services as justification for biodiversity conservation. Austral Ecol. 2020, 45, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogendoorn, K.; Gross, C.L.; Sedgley, M.; Keller, M.A. Increased tomato yield through pollination by native Australian Amegilla chlorocyanea (Hymenoptera: Anthophoridae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2006, 99, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammet, R.; Andres, H.; Dreesmann, D. Human-insect relationships: An ANTless story? Children’s, adolescents’, and young adults’ ways of characterizing social insects. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, M. Blue-Banded Bee Named 2024 ABC Australian Insect of the Year as Thousands Vote in Inaugural Poll. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-11-09/blue-banded-bee-australian-insect-of-the-year-inaugral-vote/104572938 (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Evershed, N.; Ball, A. Voter fraud detected in Guardian’s Australian bird of the year poll. The Guardian, 11 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, G.B.; Schlegel, J.; Kauf, P.; Rupf, R. The Importance of Being Colorful and Able to Fly: Interpretation and implications of children’s statements on selected insects and other invertebrates. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2015, 37, 2664–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, J.; Breuer, G.; Rupf, R. Local Insects as Flagship Species to Promote Nature Conservation? A Survey among Primary School Children on Their Attitudes toward Invertebrates. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, N.J.; Bixler, R.D. Beautiful Bugs, Bothersome Bugs, and FUN Bugs: Examining Human Interactions with Insects and Other Arthropods. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, J.; Rupf, R. Attitudes towards potential animal flagship species in nature conservation: A survey among students of different educational institutions. J. Nat. Conserv. 2010, 18, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieg, A.-K.; Dreesmann, D. Promoting pro-environmental beehavior in school. factors leading to eco-friendly student action. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooykaas, M.J.; Schilthuizen, M.; Aten, C.; Hemelaar, E.M.; Albers, C.J.; Smeets, I. Identification skills in biodiversity professionals and laypeople: A gap in species literacy. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 238, 108202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, J.A. The role of taxonomy in conserving biodiversity. J. Nat. Conserv. 2002, 10, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prendergast, K. An Evaluation of the Popularity of Australian Native Bee Taxa and State of Knowledge of Native Bee Taxonomy Among the Bee-Interested Public. Insects 2025, 16, 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16111149

Prendergast K. An Evaluation of the Popularity of Australian Native Bee Taxa and State of Knowledge of Native Bee Taxonomy Among the Bee-Interested Public. Insects. 2025; 16(11):1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16111149

Chicago/Turabian StylePrendergast, Kit. 2025. "An Evaluation of the Popularity of Australian Native Bee Taxa and State of Knowledge of Native Bee Taxonomy Among the Bee-Interested Public" Insects 16, no. 11: 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16111149

APA StylePrendergast, K. (2025). An Evaluation of the Popularity of Australian Native Bee Taxa and State of Knowledge of Native Bee Taxonomy Among the Bee-Interested Public. Insects, 16(11), 1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16111149