1. Introduction

Flywheel energy storage systems (FESSs) have been widely used in the fields of power frequency modulation, rail transit, and microgrid and spacecraft energy management in recent years because of their advantages of high power density, fast response speed, and long cycle life [

1,

2,

3]. FESSs have not become a mainstream solution yet, as their manufacturing cost remains higher than electrochemical batteries, despite advantages in power density and cycle life. However, with ongoing technological advances and growing economies of scale, flywheel storage still holds broad prospects in specific applications [

3,

4]. In a magnetic levitation FESS, a magnetic bearing is used to achieve contactless support and accurate positioning of the rotor, but under abnormal conditions, such as control instability or power failure, the rotor may fall and come into contact with the mechanical protective bearing. At this time, due to the large mass and high speed of the rotor, the transient impact load can easily cause local overheating, material wear, and friction damage of the protective bearing, especially under frequent impact contact; the fluctuation of the friction coefficient may lead to serious wear aggravation, thus accelerating the failure process of the bearing [

5,

6]. Friction and wear will not only affect the operating efficiency of the bearing, but will also lead to heat accumulation, further aggravate the temperature rise, and even lead to mechanical damage or failure of the bearing in severe cases, thus endangering the safety and stability of the system’s operation. Therefore, effectively alleviating the impact load of the rolling protection bearing and suppressing the friction, wear, and temperature rise under drop conditions have become key issues in the safety design of FESSs [

7,

8].

Existing improvement measures mainly focus on improving performance by optimizing the bearing’s structure and materials, such as adopting a bionic structure design, improving the permanent magnet layout, improving eddy current damping capacity, etc., to enhance the bearing’s capacity and durability. Du et al. [

9] reviewed the research progress and key technical paths of magnetic bearings and pointed out that, in traditional rolling protection bearings, it is difficult to balance the bearing’s capacity and temperature resistance under high-speed conditions. Yu et al. [

10] studied a modular permanent magnet thrust bearing unit with a bionic structure, which significantly improved the load capacity of the bearing through multi-unit composite design and provided a new structural idea for high-energy-density FESSs.

In a magnetic levitation flywheel energy storage system, the Halbach array can generate a strong concentrated magnetic field on one side of the rotor through its unique arrangement of permanent magnets and at the same time achieve magnetic field shielding on the other side, thereby significantly improving the air gap magnetic density and axial magnetic force. This structure not only enhances the non-contact support ability of the rotor during the drop, but also effectively reduces eddy current loss and temperature rise and improves the dynamic stability and impact resistance of the system [

11]. In addition, the high magnetic field uniformity of the Halbach array helps to reduce the vibration and yaw of the rotor during high-speed rotation, thereby prolonging the service life of the protective bearing and providing an important magnetic guarantee for the safe operation of the flywheel rotor under abnormal working conditions. Asadi et al. [

12] reviewed the application of a Halbach array in an energy harvesting and magnetic levitation system and the results showed that this structure can effectively enhance magnetic field concentration and improve magnetic energy utilization. Lu et al. [

13] established a three-dimensional analytical model of eddy current coupling in a Halbach array based on magnetic scale potential and H function, which verified the high accuracy and applicability of this method in magnetic field distribution and magnetic force prediction and provided a theoretical basis for the magnetic field optimization of permanent magnet bearings. Deshwal et al. [

14] analyzed the eddy current damping characteristics of a multi-ring permanent magnet thrust bearing and the results showed that a reasonably designed eddy current damping structure can effectively reduce transient shock and vibration response. Shuaibu et al. [

15] systematically reviewed the latest progress of coreless axial flux permanent magnet motors and pointed out that permanent magnet layout optimization and lightweight design are key directions for improvement of the performance of high-speed rotating equipment. Toh et al. [

16] established the magnetic analytical model of the annular Halbach array structure and verified its static suspension and axial support characteristics in an annular FESS, which provided a reference for the design of permanent magnet axial bearings based on Halbach structures. Xu et al. [

17] systematically analyzed the development trend of FESS technology and pointed out that although magnetic bearings have the advantages of being frictionless and long-life, the research on protection mechanisms under abnormal working conditions is still insufficient. Liang et al. [

18] analyzed the bearing stiffness of a flux-switched permanent magnet motor with a five-degree-of-freedom bearingless rotor. Their results indicate that this motor structure exhibits superior stiffness in multi-degree-of-freedom magnetic levitation systems, thereby enhancing system stability and load capacity. Falkowski et al. [

19] studied a radial passive magnetic bearing based on the Halbach array and the results show that the structure can realize unilateral magnetic field strengthening and high stiffness support, which provides a reference idea for non-contact protection of high-speed rotating equipment. Wang et al. [

20] investigated a novel axial hybrid magnetic bearing for flywheel energy storage systems, integrating permanent magnet and electromagnetic technologies. The results demonstrate that this design enhances the bearing’s load capacity and stability, while also improving the dynamic response and overall control performance of the flywheel system. Hu et al. [

21] studied the wear characteristics and performed a mechanism evaluation of high-speed petal-type permanent magnet rotor series bearings (HPMRSBs) in a vacuum environment and the results showed that this type of bearing shows excellent wear resistance under high-speed and vacuum conditions, and its wear mechanism was different from that of traditional bearings, which could effectively improve the durability and performance of bearings.

In addition, some studies focus on slowing down the friction and wear process and improving the fatigue life of bearings by optimizing the friction performance, reducing the friction coefficient, or strengthening the fatigue strength of bearings, in order to deal with possible friction damage and fatigue failure problems under extreme working conditions [

22]. Prathik Kamath et al. [

23] systematically reviewed friction and friction control strategies in active magnetic bearing systems, pointing out the importance of friction reduction and contact behavior control for prolonging system life and summarizing the research progress related to control and friction in recent years. Hu et al. [

24] investigated the effect of the static-dynamic aging wear of grease on the life of high-performance bearings. Through prediction and evaluation, how grease aging affects the performance and service life of bearings is discussed, which provides a reference for the optimal design of high-performance bearings. Lai et al. [

25] studied the method of controlling the surface properties of precision bearing raceways by using wireless sensing technology. Through the combination of CBN grinding wheels and wireless sensors, the improvement in the surface performance of precision bearings was evaluated and an effective surface optimization strategy was proposed. Hu et al. [

26,

27] analyzed the wear mechanism of elastic-flexible thin-walled bearings and ultra-thin-walled bearings under extreme working conditions, respectively, and proposed an effective design optimization strategy to improve their wear resistance and fatigue life under high-load conditions. Neisi et al. [

28] evaluated the performance of ground-touching bearings through model and experimental data, studied the contact force and friction behavior of bearings under different working conditions, and discussed the influence of friction and wear on bearing performance. Olejnik et al. [

29] studied the magnetic field distribution and energy loss of a permanent magnet linear synchronous motor under the condition of slip-viscous friction. The results show that the influence of friction leads to uneven magnetic field distribution of the motor and significantly increases the energy loss of the system, thus affecting the overall efficiency and performance of the motor.

In recent years, many studies have focused on improving the fatigue life of materials and structures. Wang et al. [

30] reviewed the recent progress in fatigue life prediction of additive manufacturing metal materials, emphasizing the combination of data-driven and physical information methods to improve prediction accuracy. Wang et al. [

31] developed a physics-guided machine learning framework specifically for the fatigue life prediction of AM materials, which provides a reliable method for fatigue performance prediction of AM materials under complex loading conditions. Ahmadi et al. [

32] proposed a comprehensive approach, from microstructure design to surface engineering, for enhancing the fatigue life of additively manufactured metabiomaterials, demonstrating that optimizing microstructure and surface treatment can significantly improve fatigue performance. Das and Jones [

33] explored ways to improve fatigue life through shape optimization technology, showing that well-designed shape improvement can reduce stress concentration, thus prolonging the fatigue life of structures. These studies provide valuable insights into improving the durability and fatigue life of materials under different working conditions.

Generally speaking, the existing research has made remarkable progress in structural design, magnetic field modeling, and load performance improvement of permanent magnet bearings, but there are still some limitations. Particularly in FESSs, the unloading mechanism, magnetic coupling characteristics, and parameter optimization law of the Halbach array used to protect bearings are still lacking systematic and in-depth research. Based on this, this paper proposes a permanent magnet axial protective bearing structure based on a Halbach array to solve the problem that the traditional protective bearing in vertical magnetic levitation FESSs is susceptible to impact and wear temperature rise under drop conditions. Firstly, parametric analysis is carried out to optimize bearing geometry and polarization configuration. Secondly, the rotor drop dynamic model and system thermal analysis model are established and the unloading characteristics and temperature rise suppression of permanent magnet bearings are studied. Finally, the friction and wear behavior of permanent magnet materials under different loads, frequencies, and temperatures is studied by linear contact fretting friction experiment, which aims to provide an experimental basis for the performance evaluation of permanent magnet axial protective bearings.

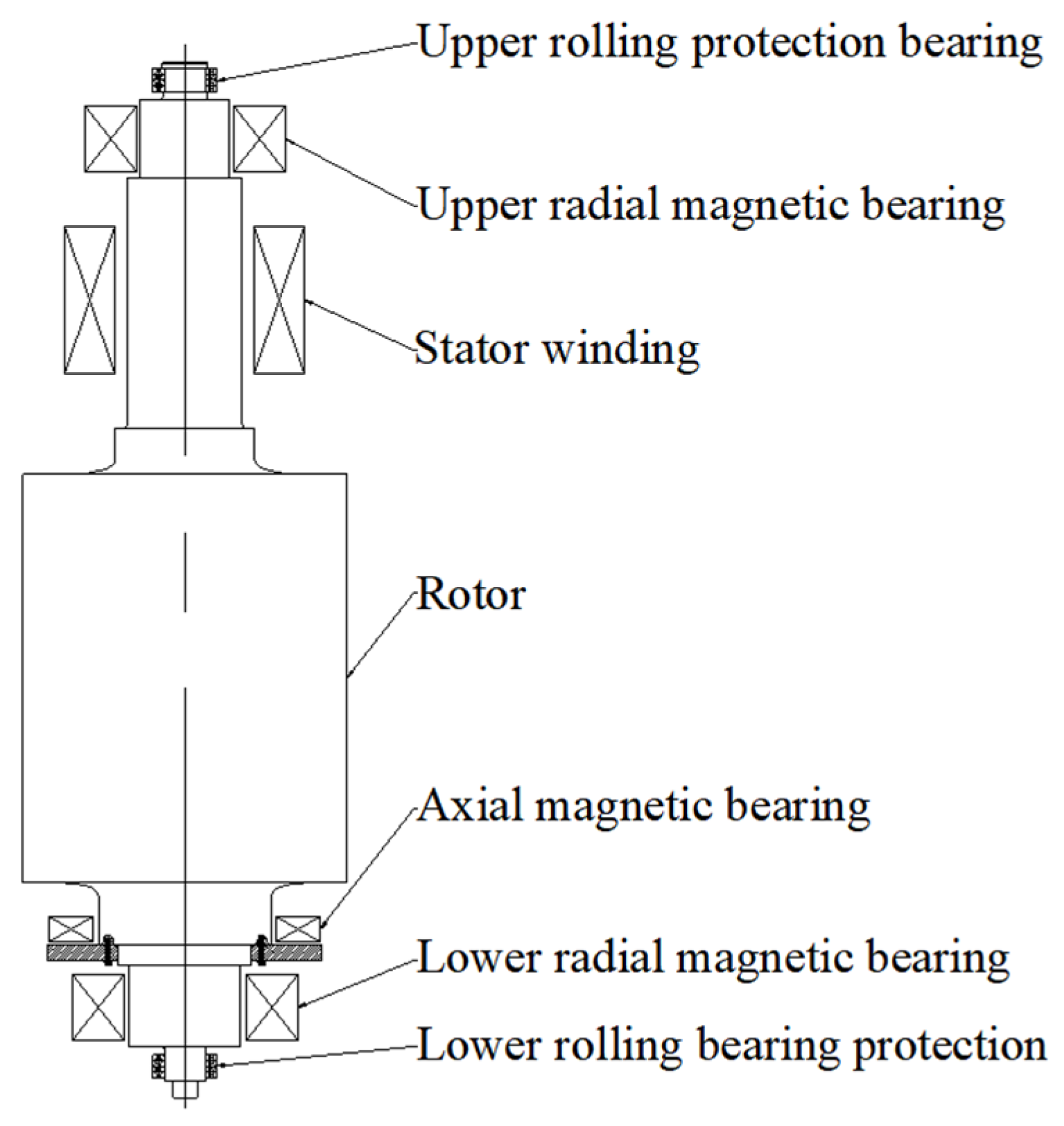

2. Establishment of the Vertical Rotor Drop Model

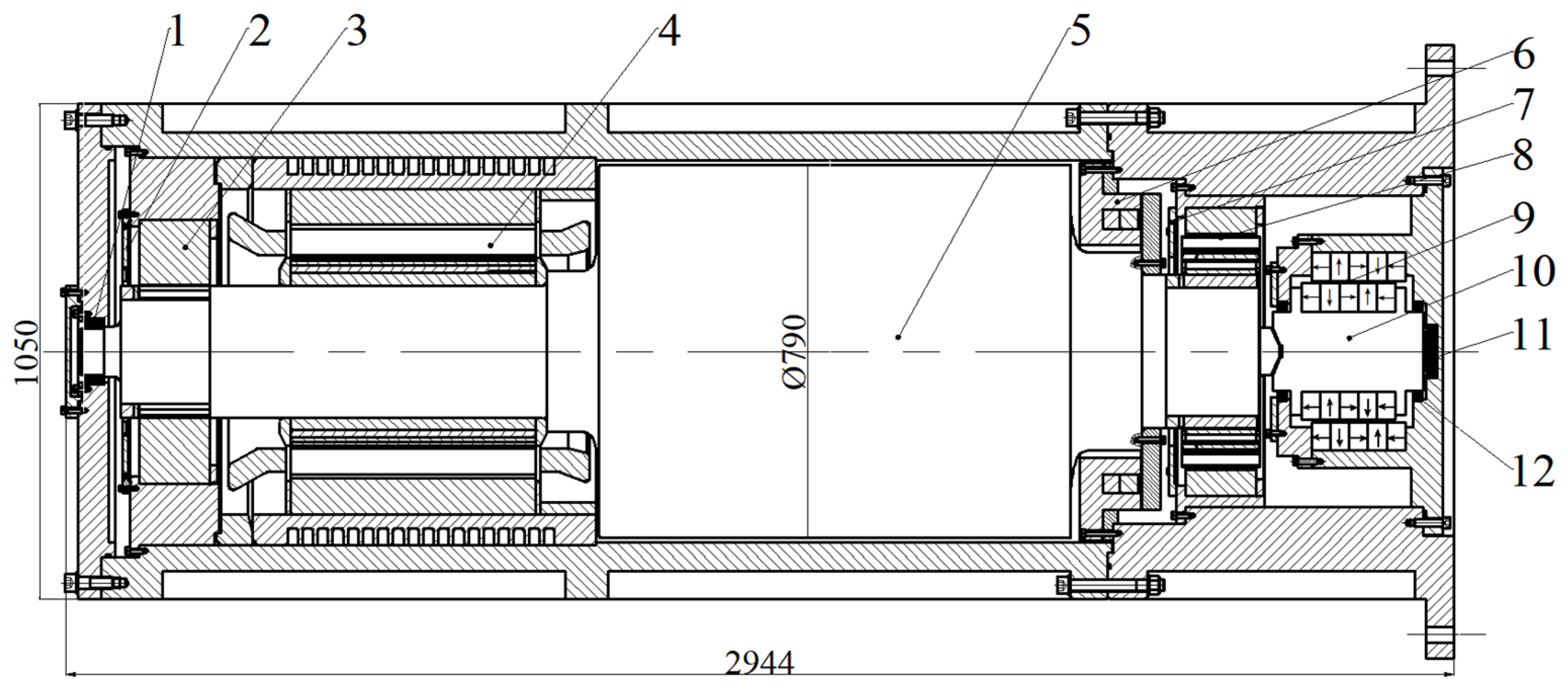

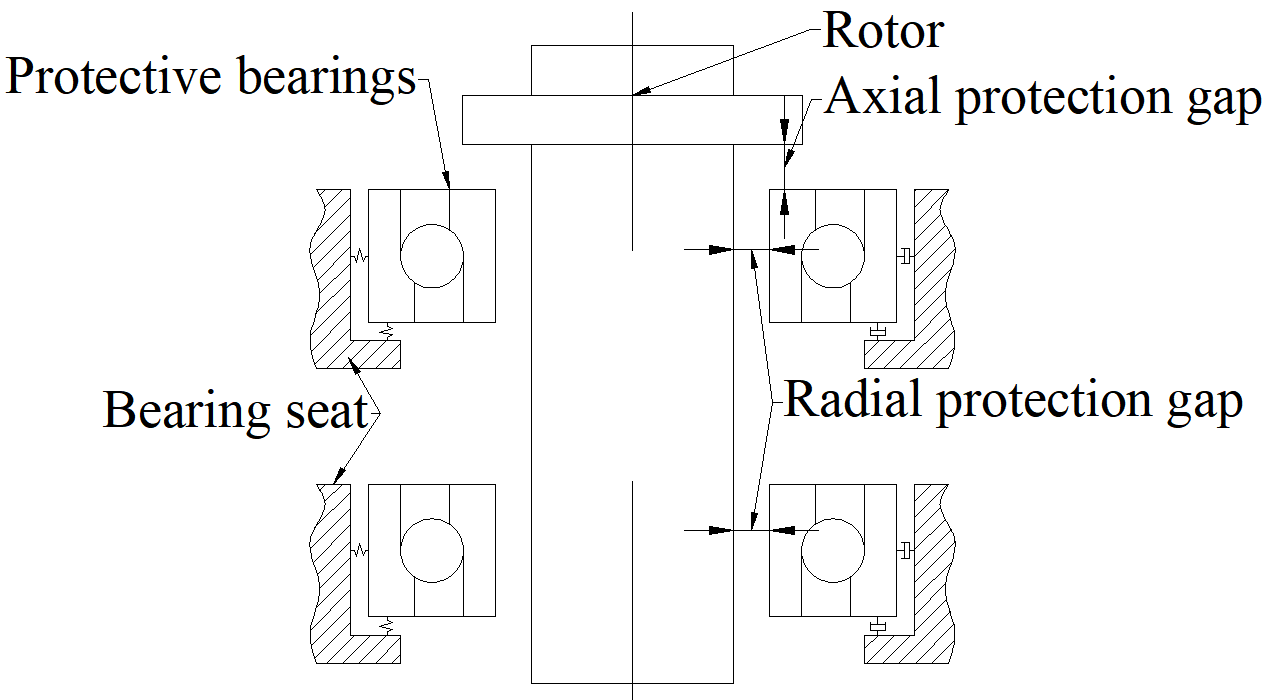

The vertical magnetic levitation rotor drop system is mainly composed of a rotor, a stator winding, upper and lower sets of radial magnetic bearings, one set of axial magnetic bearings, and upper and lower sets of rolling protection bearings (

Figure 1). Protective bearings are arranged at both ends of the rotor to provide mechanical support and operation protection under abnormal working conditions such as system instability or power failure. The protective bearings at both ends adopt an angular contact ball bearing structure in a “face-to-face” configuration. In the process of rotor drop, the upper protective bearing needs to bear both axial and radial loads, while the lower protective bearing mainly bears radial loads.

2.1. Kinetic Model

After simplifying the vertical magnetic levitation rotor drop system, the rotor-protective bearing model shown in

Figure 2 is obtained. The dynamic model of the upper protective bearing mainly considers the axial–radial coupling load when the rotor falls, especially the large axial force it bears. Therefore, the model introduces axial and radial dynamic coupling to analyze the axial vibration of the rotor and the contact force with the bearing; the lower protective bearing model focuses on the radial impact load, uses the simplified radial dynamic model to simulate the contact and friction force, and analyzes the radial force change and system damping, excluding the obvious axial action. In contrast, the upper protective bearing is more prone to stress concentration and fatigue damage during the drop because it bears significant axial and radial loads at the same time, and usually fails before the lower protective bearing in actual operation. Therefore, this model focuses on the dynamic behavior of the upper protective bearing during rotor drop and its effects to more accurately reflect the key damage mechanisms of the system.

When the rotor falls, it is supported by upper and lower groups of protective bearings and its vortex forms mainly include cylindrical motion and conical motion. During the cylindrical motion, the whole rotor periodically impacts the protective bearing with a large radial amplitude, resulting in concentrated contact force and frequent impact, which is can easily cause bearing damage. Conical motion contains axial oscillation components, which can disperse the contact area and load, thus reducing impact damage. Due to the large span of the upper and lower protective bearings, the rotor attitude has little influence on the dynamic response of the system. When the vertical magnetic levitation rotor system fails and falls, it is easier for the rotor to enter a cylindrical motion mode, and the motion states at the protective bearings at both ends are basically the same [

34].

The research object is the rigid rotor during the drop process. To describe its motion characteristics, the displacement (

x,

y,

z) of the rotor’s center of mass in the radial and axial directions, as well as the rotation angle

θ around the rotating axis, are selected as the generalized coordinates of the system. Based on this, a dynamic model of the rotor drop process was established using the Lagrange equation.

In the formula,

T represents the kinetic energy of the rotor,

V represents the potential energy of the rotor,

F represents the generalized dissipation function,

qi represents the generalized coordinates, and

Qi represents the generalized force. The rotor drop dynamics equation in the direction of each degree of freedom can be expressed as follows:

In the formula, mr represents the mass of the rotor, Jr represents the moment of inertia of the rotor, and c represents the damping coefficient.

2.2. Collision Contact Force Model

In this paper, the Lankarani–Nikravesh contact force model [

35] is used to describe the collision behavior between the rotor and the protective bearing. The model is especially suitable for impact analysis in rotor dynamics because it enables accurate consideration of energy dissipation during medium-to-high-speed collisions, which is the core feature of rotor drop events. Compared with the classical Hunt–Crossley model [

36], this model can more accurately reflect the energy dissipation characteristics of materials under different impact velocity and temperature conditions by introducing velocity-related recovery coefficients. In addition, the model adds a viscous correction related to the penetration depth to the damping term, which effectively avoids the numerical singularity problem that may occur at the initial stage of contact, and thus more accurately describes the energy dissipation during the collision process. The recovery coefficient and stiffness coefficient are obtained by experimental calibration. In the controlled drop experiment, the contact force, displacement, and velocity data were acquired synchronously by varying the initial velocity and protective clearance. The recovery coefficient is directly obtained by calculating the ratio of the velocity before and after the collision; the stiffness coefficient is determined by fitting the relationship curve between contact force and penetration depth. This method provides a reliable parameter basis for the collision force model and ensures the accuracy of the model. The established normal contact force model can effectively characterize the nonlinear collision response between the rotor and the protective bearing during the rotor drop. Its mathematical expression is as follows, in Equation (3).

In Equation (3), Fn represents the contact force, e represents the recovery coefficient related to speed–temperature, ν represents the initial velocity at contact, δ represents the penetration depth, and K represents the contact stiffness.

In the process of rotor drop, both axial and radial contact surfaces will produce sliding friction and accompanied wear. Although the classical Coulomb friction model is simple in form, its inherent discontinuity easily leads to the decline of numerical accuracy and difficulty in convergence. Therefore, the improved Coulomb friction model [

37] and the Archard wear model [

38] are used to calculate the contact friction force and wear amount, respectively, and their expressions are as follows, in Equations (4) and (5).

In Equations (4) and (5), Fm represents the contact friction force, Fn represents the contact force, μ represents the coefficient of friction, νh represents the relative sliding speed of contact, Vc represents the volume of material wear, s represents the relative sliding distance of the contact surface, A represents the dimensionless coefficient of friction, and H represents the Brinell hardness value of the material.

2.3. System Heat Generation Model

According to the analysis of the rotor-protective bearing drop model, the main heat source of the system includes three parts: radial contact friction between the rotor and protective bearing inner ring, axial contact friction between the rotor and protective bearing end face, and friction between protective bearing rolling elements and the inner and outer rings. The total heat generation

H of the system can be expressed as follows [

39]:

The following describe Equation (6): Ha, Hr, and Hc, respectively, represent the heat generated by axial friction between the rotor and the inner ring of the protection bearing, the heat generated by radial friction, and the heat generated inside the protection bearing; νr represents the relative velocity between the rotor and the inner ring at the radial contact point; Ma represents the end face friction torque; θr and θb represent the angle changes in the rotor and the angle changes in the inner ring of the protective bearing; ωb represents the angular velocity of the rolling elements; ωn and ωw represent the spin angular velocity of the rolling elements in contact with the inner and outer rings; Mi,j and Mo,j represent the the viscous friction torque between the rolling elements and the inner and outer rings; Mn and Mw represent the spin torque of the inner and outer rings.

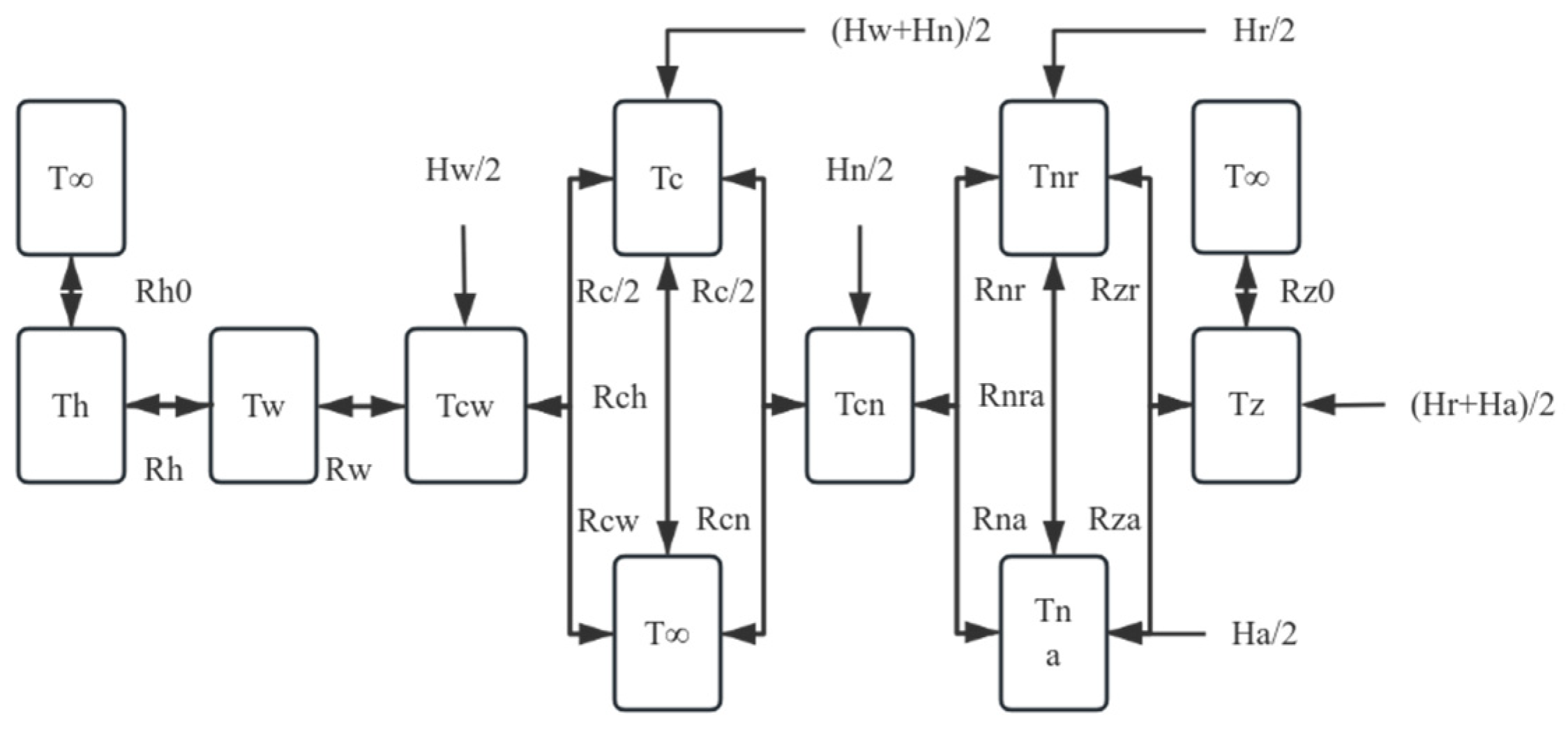

In addition, the heat transfer model of the system needs to be established. The model mainly considers the heat transfer between the rotor, the protective bearing, and the bearing seat. A temperature node network is established based on the following assumption: each heat source generates heat uniformly on the contact surface and the heat is uniformly conducted in the protective bearing and rotor [

40]. According to the thermal principle, the heat transfer efficiency between nodes is determined by the contact thermal resistance. Based on this, the heat transfer grid model of the system in

Figure 3 is established.

Among them, T represents temperature; R represents heat transfer impedance; the subscripts h, w, cw, c, cn, n, z, r, and a, respectively, indicate the bearing housing, the outer ring of the protection bearing, the outer ring raceway, the rolling elements, the inner ring raceway, the inner ring, the rotor, and the radial and axial directions. T∞ indicates room temperature.

Based on the heat transfer grid method, the energy exchange relationship between each temperature node can be expressed as a set of first-order thermal differential equations [

41]. By solving this system of equations, the temperature dynamic response of the system can be obtained.

In Equation (7), m represents mass, C represents specific heat capacity, and δQ represents the heat flux of the node.

3. Design of Permanent Magnet Axial Protective Bearing

The FESS has a rated power of 1.2 MW, a rotor mass of 4500 kg, and a limit speed of 8000 rpm. The rotor drop condition imposes stringent demands on the load capacity and life of the rolling protection bearings. To address this, permanent magnet axial protection bearings are incorporated into the system to provide additional axial protection. These bearings are independently arranged. Matching conical grooves on both the flywheel rotor and the permanent magnet bearing rotor ensure centering and self-locking. During a rotor drop, the permanent magnet bearing rotor moves with the flywheel rotor, providing supplementary axial support. This significantly reduces the axial and radial friction on the rolling protection bearings, thereby effectively suppressing temperature rise, extending bearing life, and enhancing the system’s drop endurance.

Figure 4 is a two-dimensional engineering drawing of FESS (with the gravitational direction pointing to the right).

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional engineering drawing of the FESS: 1—rolling protection bearings; 2, 7—differential inductive displacement sensors; 3, 8—radial magnetic bearings; 4—stator winding; 5—rotor; 6—axial magnetic bearing; 9—permanent magnet axial protection bearing; 10—permanent magnet rotor; 11—elastic damping system; 12—permanent magnet rotor auxiliary bearing.

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional engineering drawing of the FESS: 1—rolling protection bearings; 2, 7—differential inductive displacement sensors; 3, 8—radial magnetic bearings; 4—stator winding; 5—rotor; 6—axial magnetic bearing; 9—permanent magnet axial protection bearing; 10—permanent magnet rotor; 11—elastic damping system; 12—permanent magnet rotor auxiliary bearing.

The choice of a Halbach array over a hybrid permanent magnet electromagnetic design is mainly based on the specific requirements of protecting the bearing under fault conditions. As a backup component for starting in case of drop, the protective bearing must have extremely high reliability, instantaneous response capability, and be completely independent of external power and control systems. As a fully passive structure, a Halbach array generates a strong unilateral magnetic field through only the arrangement of permanent magnets, without an external power supply and control, thus avoiding the risk of power supply or control failure in hybrid systems. Although the hybrid design can provide excellent controllability when the main bearing is operating normally, the first task of protecting the bearing is to provide a definite and sufficient axial bearing capacity at the moment of failure. A Halbach array is more in line with the requirements of this passive protection role due to its high magnetic density, simple structure, robustness, and maintenance-free characteristics.

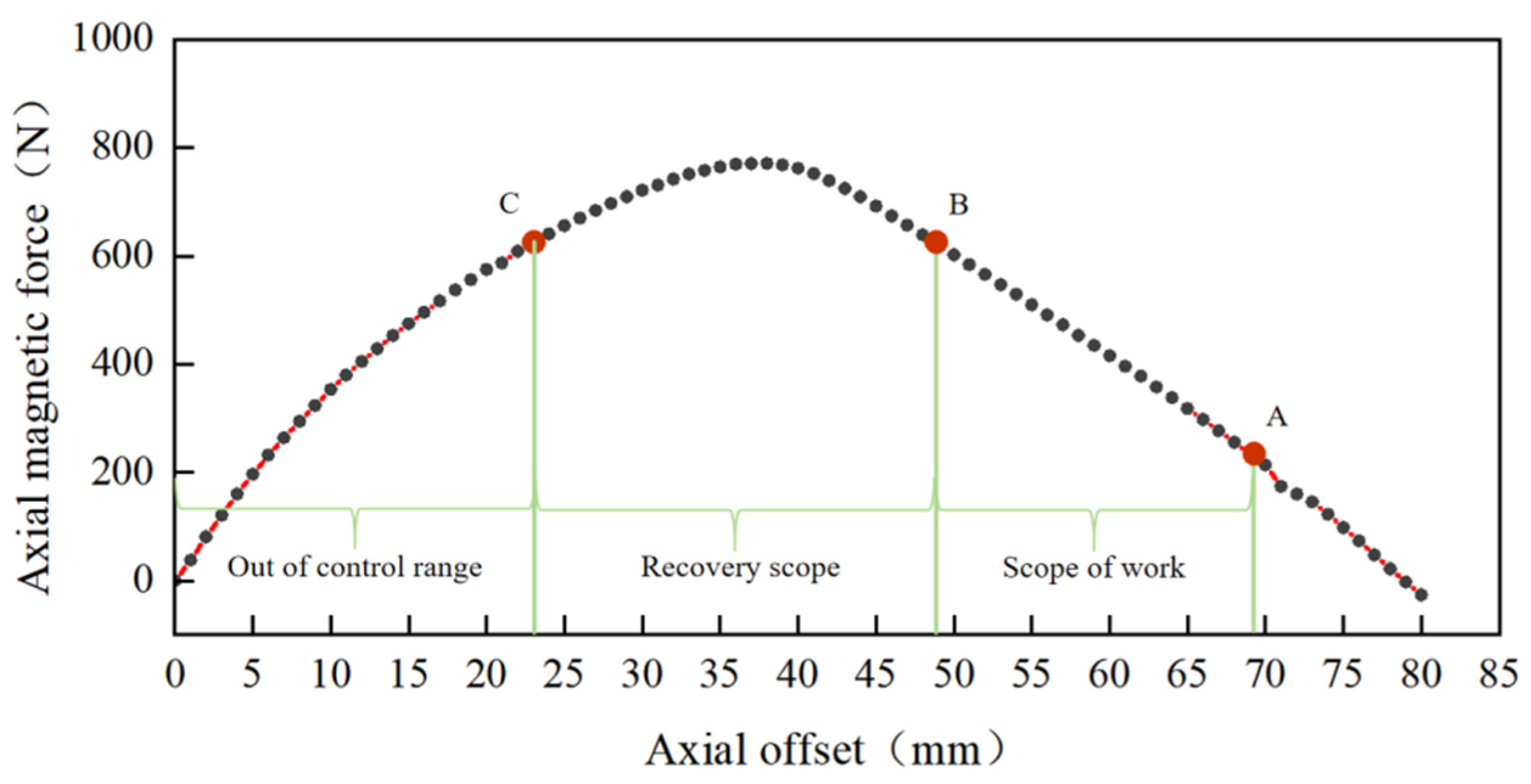

Figure 5 illustrates the working principle of the permanent magnet axial protective bearing based on the axial force-displacement characteristics of the inner magnetic ring assembly. Before the flywheel rotor drops, the axial magnetic force balances the combined gravity of the permanent magnet rotor and the pressure plate at point A. After the drop, the inner magnetic ring group must support the total weight of both the flywheel rotor and the permanent magnet rotor, shifting the balance point to B. To ensure effective operation under drop conditions, the working and recovery range of the bearing must be expanded. The key to achieving this lies in increasing the maximum axial magnetic force.

Figure 5.

Relationship between axial magnetic force and axial offset in the magnetic ring group in a Halbach array stacked structure.

Figure 5.

Relationship between axial magnetic force and axial offset in the magnetic ring group in a Halbach array stacked structure.

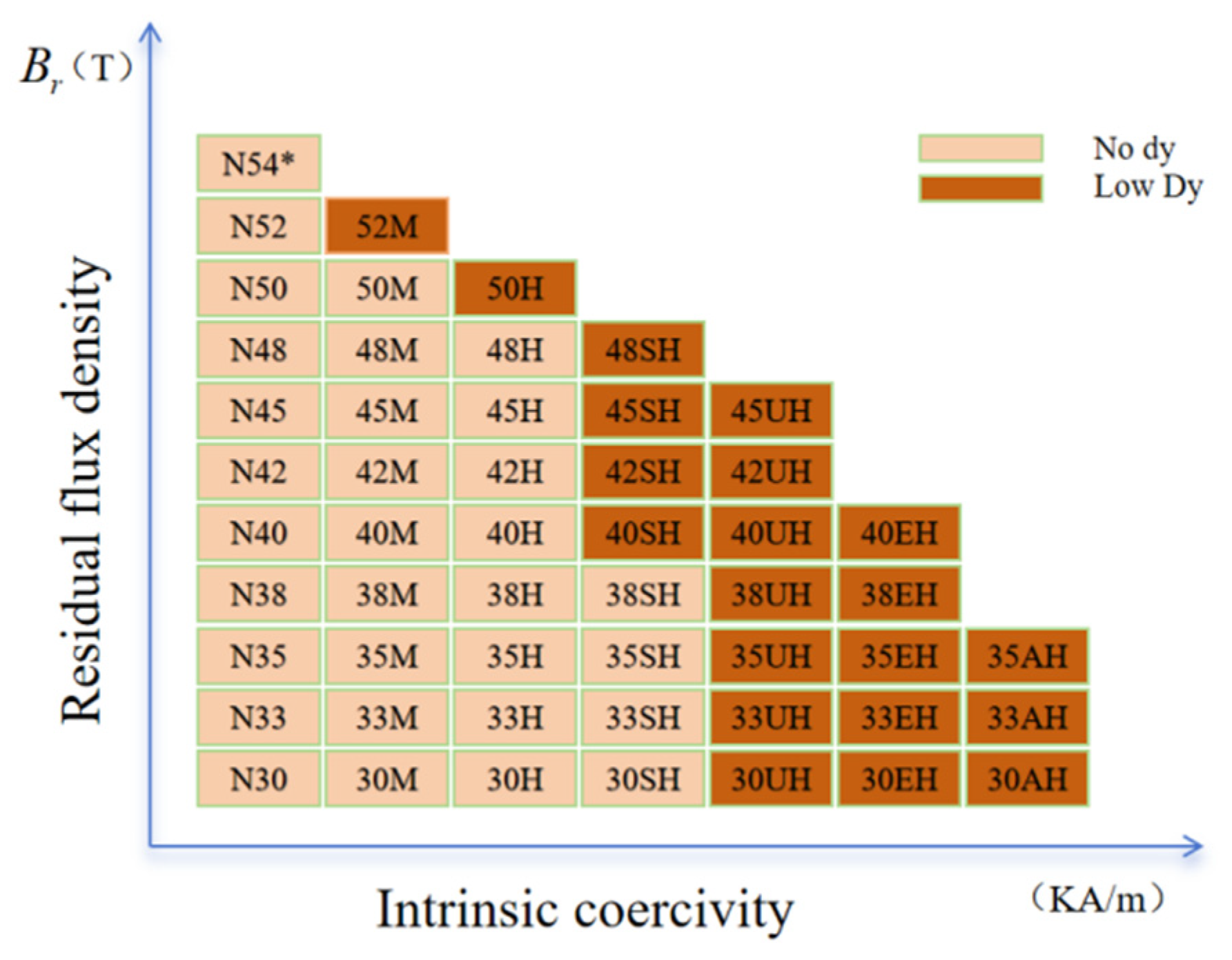

The selection of NdFeB permanent magnets requires a balanced consideration of remanence and intrinsic coercivity. The numerical part of the grade designation, such as N42, reflects the remanence level, which serves as the primary basis for magnetic circuit design. The suffix letters, for example, SH, indicate the intrinsic coercivity grade, which corresponds to different maximum operating temperatures—approximately 100 °C for M grade and 150 °C for SH grade according to reference [

42]. Consequently, the selection process involves first determining the numerical grade based on the magnetic requirements, then choosing the suffix letter according to the system’s thermal design, thereby finalizing the specific magnet grade. The relationship between remanence and coercivity for various grades is illustrated in

Figure 6.

The selection of permanent magnets needs to meet two key indicators: in view of the fact that the temperature of the flywheel system is close to 100 °C when it falls, in order to retain a sufficient safety margin, the magnet with a temperature resistance grade of SH is selected; and, at the same time, based on the magnetic circuit design requirements, the material remanence needs to be higher than 1.3 T. Accordingly, the final selection of N42SH grade is based on the comprehensive trade-off between a high temperature tolerance and a high magnetic energy product. Among materials that meet the high temperature requirements of the SH grade, N42 provides the level of remanence required to be able to achieve the target magnetic force. This choice ensures that the permanent magnet bearing can still work stably in the high temperature environment generated by rotor drop and provides sufficient non-contact support. Its specific performance parameters are shown in

Table 1 below.

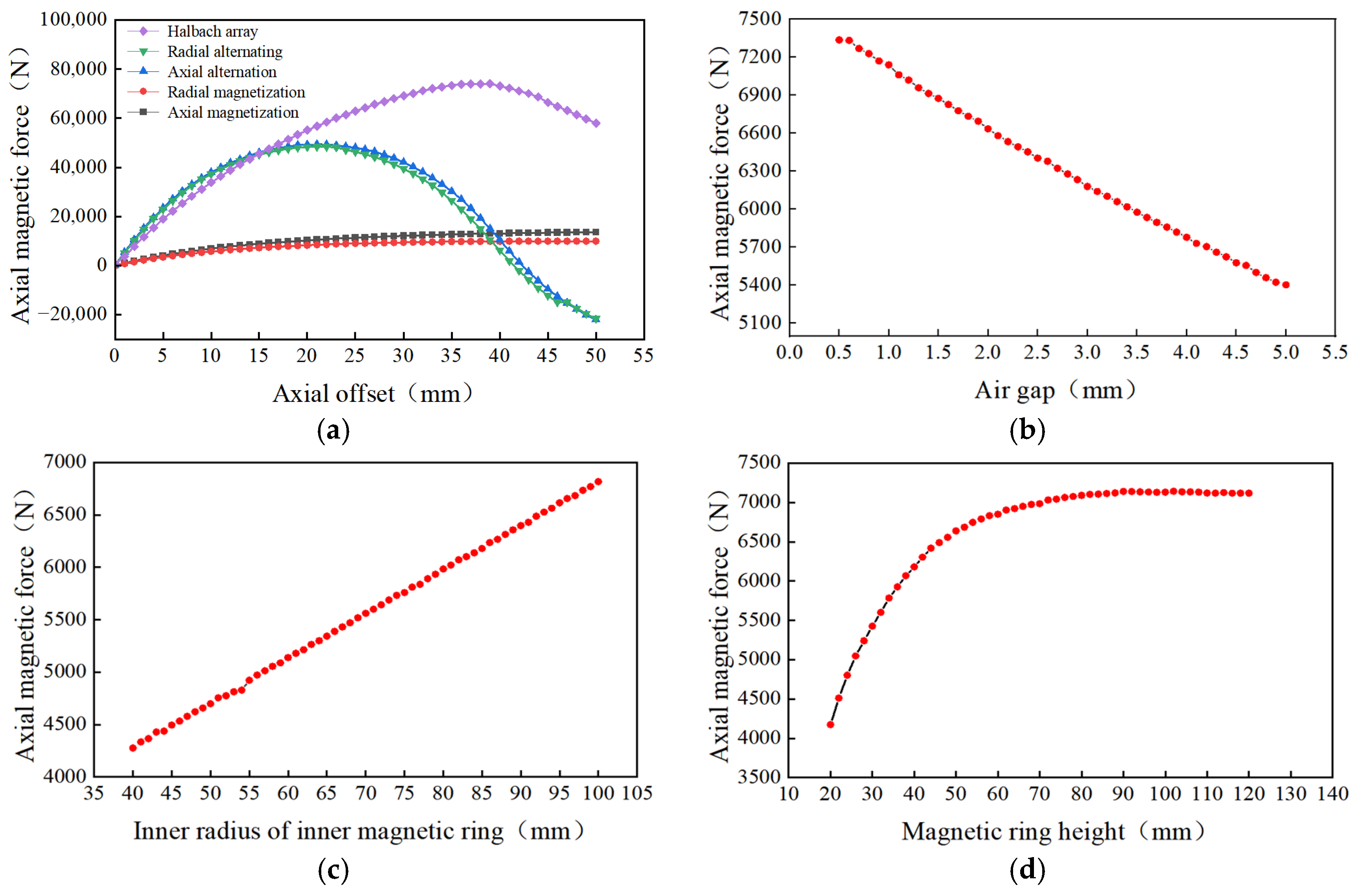

To systematically investigate the axial force characteristics of permanent magnet bearings, this study selected four key design parameters for analysis: the magnetization mode of the inner and outer magnetic rings, the working clearance (air gap), and the inner diameter of the inner magnetic ring and its thickness-to-height ratio. These parameters collectively determine the magnetic circuit distribution and air gap magnetic field intensity, which are the core factors governing axial bearing performance. The specific influence of each parameter on the axial force is presented in

Figure 7.

Figure 7a demonstrates the superior performance of the Halbach array compared to other magnetization methods, particularly in generating axial magnetic force. Within the axial displacement range, the Halbach array produces a significantly higher magnetic force, maintaining a high output level even at offsets up to 45 mm. This indicates higher magnetic force density and more efficient magnetic force transfer. Furthermore, the magnetic force curve of the Halbach array exhibits relatively gentle fluctuations compared to radial or axial alternation methods, contributing to system stability—a crucial factor for high-precision applications. Additionally, the Halbach array maintains strong magnetic output under large axial offsets, demonstrating good fault tolerance and its ability to mitigate adverse effects from axial displacement. These characteristics give the Halbach array distinct advantages in permanent magnet protective bearing design, especially for enhancing system stability and magnetic output efficiency.

Figure 7b illustrates the relationship between air gap size and axial magnetic force. As the air gap increases, the axial magnetic force gradually decreases, indicating reduced magnetic force transfer efficiency. Specifically, within the 0 to 5 mm air gap range, the axial magnetic force shows a smooth, declining trend. This behavior aligns with fundamental magnetic circuit principles, where an increased air gap reduces the magnetic flux density, thereby weakening the axial magnetic force.

Figure 7c presents the effect of the magnetic ring’s inner radius on axial magnetic force. The axial magnetic force increases linearly with the inner radius, meaning a larger inner radius enhances the achievable axial force. This is attributed to the increased cross-sectional area of the magnetic flux path, which improves the effective magnetic permeability of the circuit and enhances overall magnetic field output capability. Therefore, appropriately increasing the inner radius is an effective way to improve axial magnetic force and bearing performance.

Figure 7d shows the relationship between axial magnetic force and magnetic ring height (i.e., thickness-to-height ratio). As the height increases from 20 mm to 120 mm, the axial magnetic force initially rises and then gradually stabilizes. At lower heights, increasing the height significantly boosts the axial magnetic force by enhancing the magnetic flux density in the circuit. However, beyond a certain threshold, further height increases yield diminishing returns, with the magnetic force growth rate slowing until it stabilizes. This indicates that the magnetic ring height must be optimized to balance magnetic performance, selecting an appropriate value to achieve the best magnetic output.

Based on the analysis of these key parameters, the design of the permanent magnet axial protective bearing requires a comprehensive trade-off among axial space constraints and various structural parameters to optimize magnetic performance. To achieve high magnetic output within a limited space while considering assembly feasibility, the Halbach array was selected as the magnetization method due to its excellent axial output, stability, and fault tolerance. Following the height analysis, a thickness-to-height ratio of 2 was chosen to place the magnetic output near the optimal saturation region. Similarly, based on the air gap analysis, the magnetic ring group gap was set to 3 mm to balance magnetic force transmission efficiency and structural layout requirements. Furthermore, to ensure mechanical strength during high-speed operation, the inner diameter of the inner magnetic ring was minimized while meeting stress safety requirements.

The design must satisfy two key criteria: the maximum axial magnetic force generated by the inner magnetic ring group must exceed the rotor’s weight, and the system must possess high axial stiffness to ensure stability. The final initial design parameters derived from this analysis are summarized in

Table 2 below.

Grease is essential to protect the durability and reliability of bearings, effectively reducing friction and wear and assisting in heat dissipation. In the actual vertical magnetic levitation flywheel energy storage system, the upper and lower rolling protection bearings usually use high-performance grease to meet the operation requirements. In this study, both the upper and lower protective bearings were lubricated with BF72-23 grease.

In addition, there is a mutual exclusion relationship between the axial and radial directions in the stiffness characteristics of pure permanent magnet bearings; when the axial direction shows positive stiffness, the radial direction often shows negative stiffness, that is, radial magnetic attraction is generated. Therefore, auxiliary bearings must be introduced to counteract this radial force and provide necessary structural support for the rotor system. The selection of the auxiliary bearings was based on the system’s load rating and target life requirements, following the rolling bearing selection process outlined in the Mechanical Design Engineering Handbook (Childs, 2018) [

43]. Among common bearing types, cylindrical roller bearings offer high radial load capacity but have a low limiting speed. In contrast, angular contact ball bearings exhibit excellent high-speed performance and can withstand combined axial and radial loads, making them more suitable for high-speed applications [

44]. Based on this comparison, the angular contact ball bearing model H71920C/HQ1 was selected as the auxiliary bearing for this study. Its performance meets the system requirements in terms of radial load capacity, service life, and high-speed operation.

4. Simulation Analysis

This chapter aims to verify the validity and structural rationality of the proposed design method for the Halbach array permanent magnet axial protection bearing. To this end, finite element and rotor drop dynamic models are established using the Ansys and Matlab platforms, respectively. These models enable a systematic analysis of the bearing’s magnetic characteristics, structural strength, eddy current loss, and dynamic unloading performance under drop conditions. Special emphasis is placed on evaluating the suppression effect of the permanent magnet bearing on the contact force, temperature rise, and wear of the rolling protection bearing.

4.1. Simulation Results of Parametric Design

To evaluate the magnetic characteristics and structural strength of the permanent magnet bearings under rated working conditions, a detailed finite element simulation was performed. The analysis focused on the axial magnetic force–displacement relationship and the eddy current losses within the bearing system. The simulation was conducted using the Ansys platform, which enables precise modeling of magnetic fields and structural responses under operational conditions. Through this process, the bearing’s behavior, including its magnetic performance and energy losses, was thoroughly investigated. Key insights into the bearing’s efficiency and operational stability derived from the simulation are presented in the figures below for further analysis and discussion.

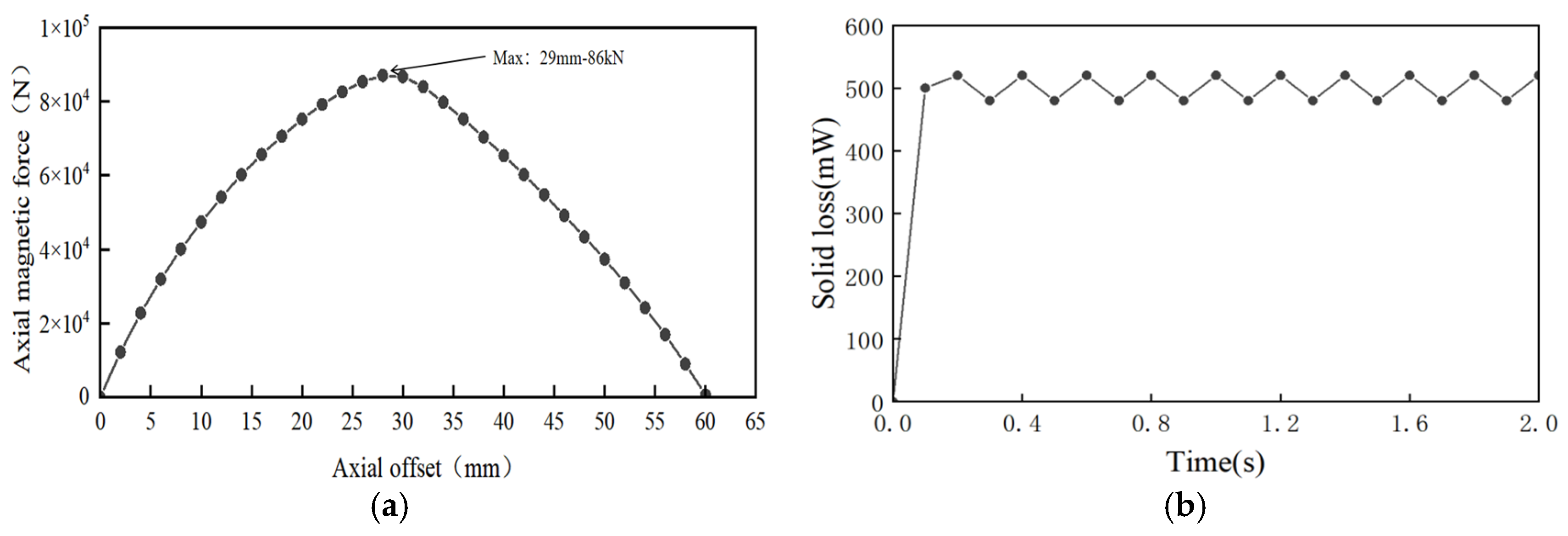

Figure 8a shows that the axial magnetic force increases nonlinearly with displacement in the range of 0–29 mm, reaching a maximum of 86 KN, which meets the design requirement for unloading force.

Figure 8b indicates that when the permanent magnet bearing operates at high speed, the high-speed cutting of magnetic field lines between the static and moving rings results in eddy current loss on their surfaces. The results show that the RMS value of the eddy current loss is 0.5 W and the overall temperature rise is controllable, demonstrating good thermal stability of the design. To further verify the structural safety of the bearing at high speed, the stress distribution at the limit speed was simulated and analyzed; the results are presented in

Figure 9.

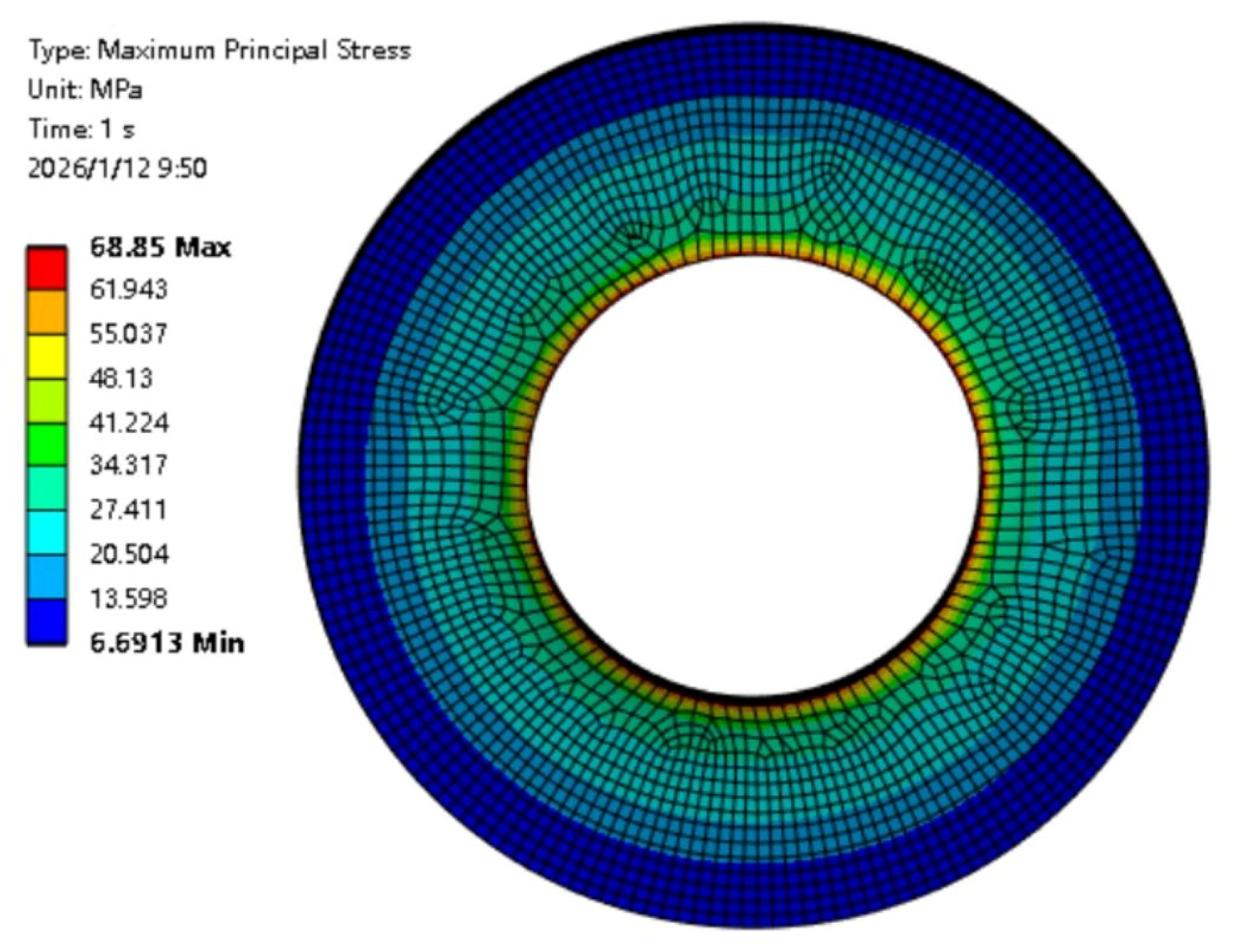

The structural strength of the permanent magnet under high-speed conditions was assessed based on the maximum principal stress. The finite element analysis results show that the peak maximum principal stress under rated working conditions is 68.85 MPa, which is lower than the tensile strength of the N42SH permanent magnet material. The stress distribution is uniform, indicating that the design meets the strength requirements with a sufficient safety margin. To further investigate the magnetic field distribution characteristics and the enhancement effect of the Halbach array, a magnetic field simulation was performed on the stacked structure of the inner and outer magnetic ring groups. The results are presented in

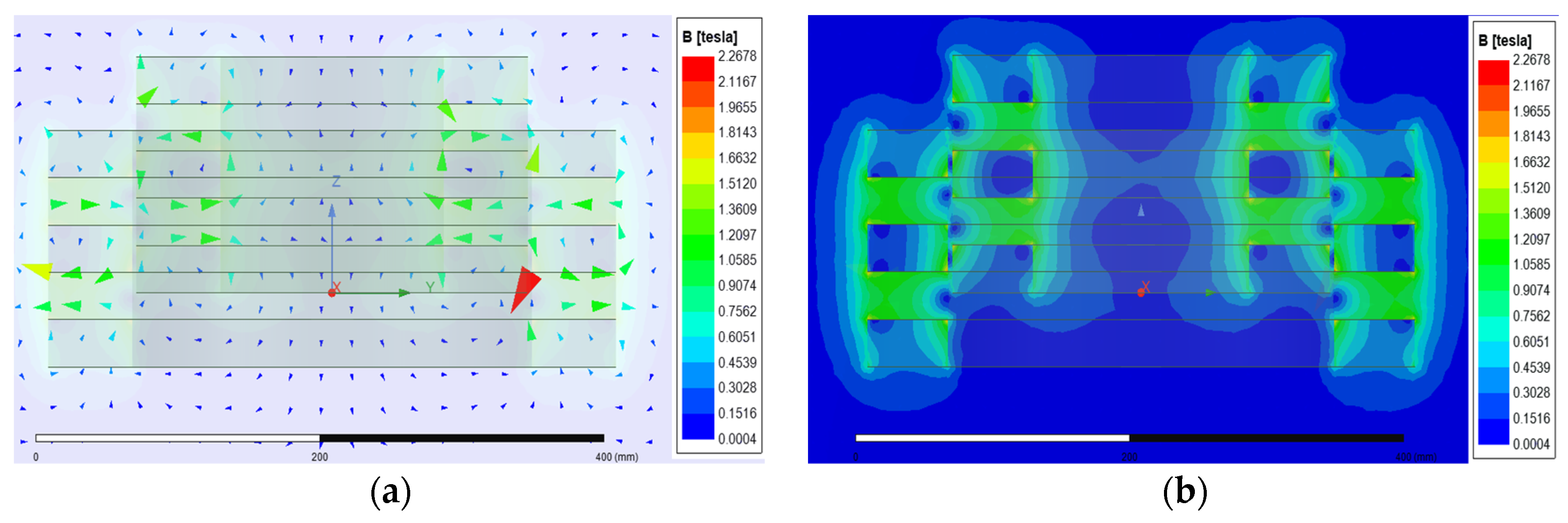

Figure 10.

The simulation results demonstrate that the Halbach array structure formed by the inner and outer magnetic rings creates a strong, concentrated magnetic field in the air gap, achieving a flux density of 2.2 T. The magnetic vector distribution shows ordered flux lines within the array and cancelation outside, confirming the unilateral enhancement and shielding effect characteristic of the Halbach configuration. The flux density contour plot further reveals a uniform and symmetrical field distribution in the air gap, with a stable closed loop between the magnetic rings and minimal flux leakage. Overall, this structure achieves high flux concentration and good symmetry, resulting in greater load capacity and high magnetic field efficiency for the permanent magnet axial protective bearing.

4.2. Temperture Rise Analysis

This study focuses on the simulation analysis of the contact force of the flywheel energy storage system when it drops at the limit speed of 8000 rpm. This working condition represents the ultimate condition, with the maximum kinetic energy of the rotor and the most severe impact load, and is a key critical scenario for testing the unloading capacity of the protective bearing. In order to comprehensively evaluate the thermal management efficiency of permanent magnet bearings, the temperature rise analysis covers two typical working conditions of 4000 rpm and 8000 rpm: 8000 rpm corresponds to the full energy reserve state of the system; however, 4000 rpm corresponds to the standby state where the energy storage of the system is only a quarter of the total energy storage.

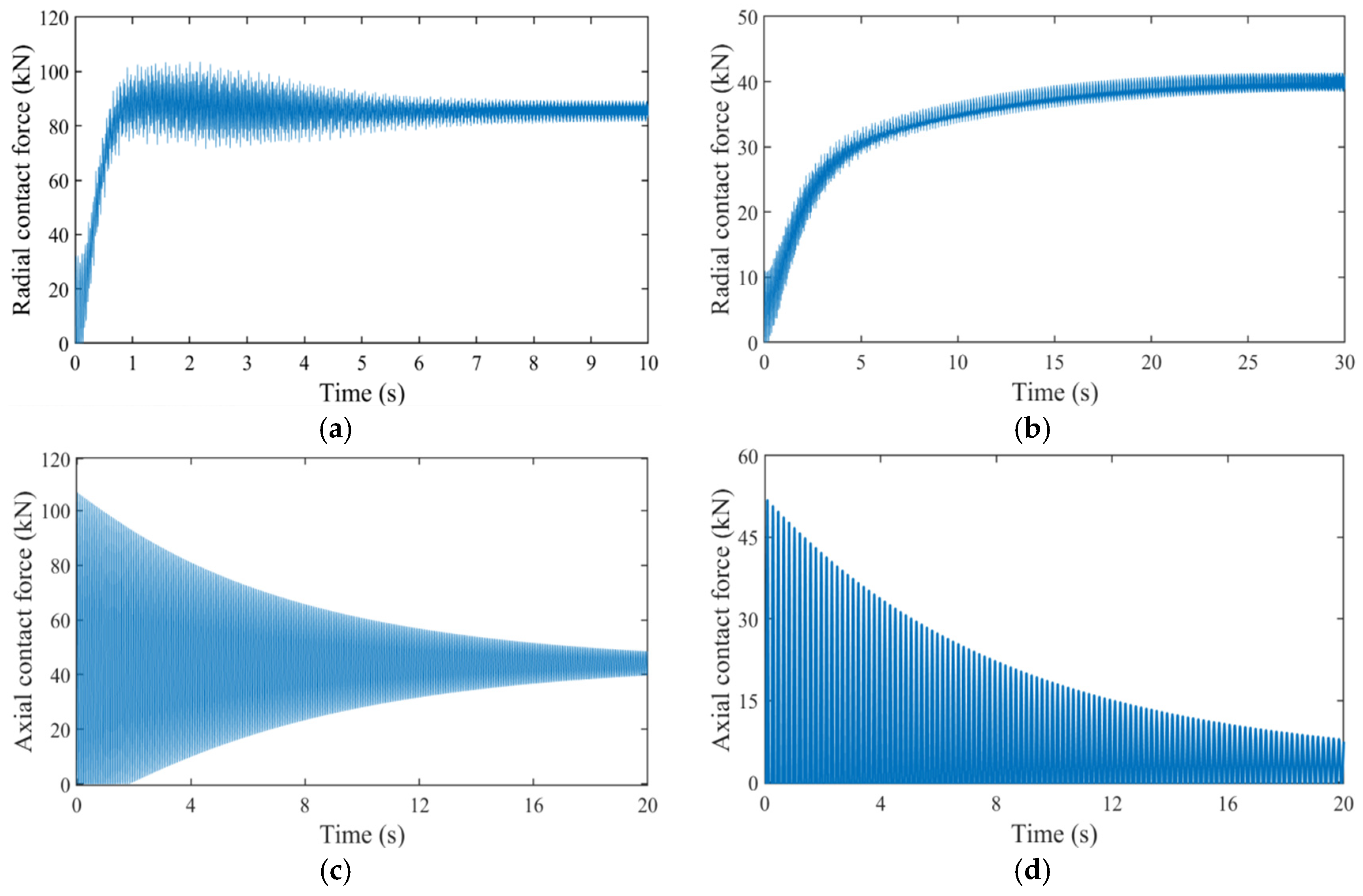

To evaluate the unloading effect of the permanent magnet bearing during the drop, the contact force between the rotor and the upper rolling protection bearing was compared and analyzed for configurations with and without the permanent magnet bearing. The simulation results of the radial and axial contact forces at 8000 rpm are presented in

Figure 11.

Figure 11a,b show that at 8000 rpm, the peak radial contact force dropped from 10 KN to 4 KN (a 60% reduction) after installing the permanent magnet bearing. Similarly,

Figure 11c,d indicate that the axial contact force decreased from 10.8 KN to 4.9 KN (≈54% reduction). These results demonstrate the bearing’s effectiveness in sharing the impact load and alleviating stress on the mechanical bearing during rotor drop. Based on the Archard wear model, the suppression of system wear was also analyzed.

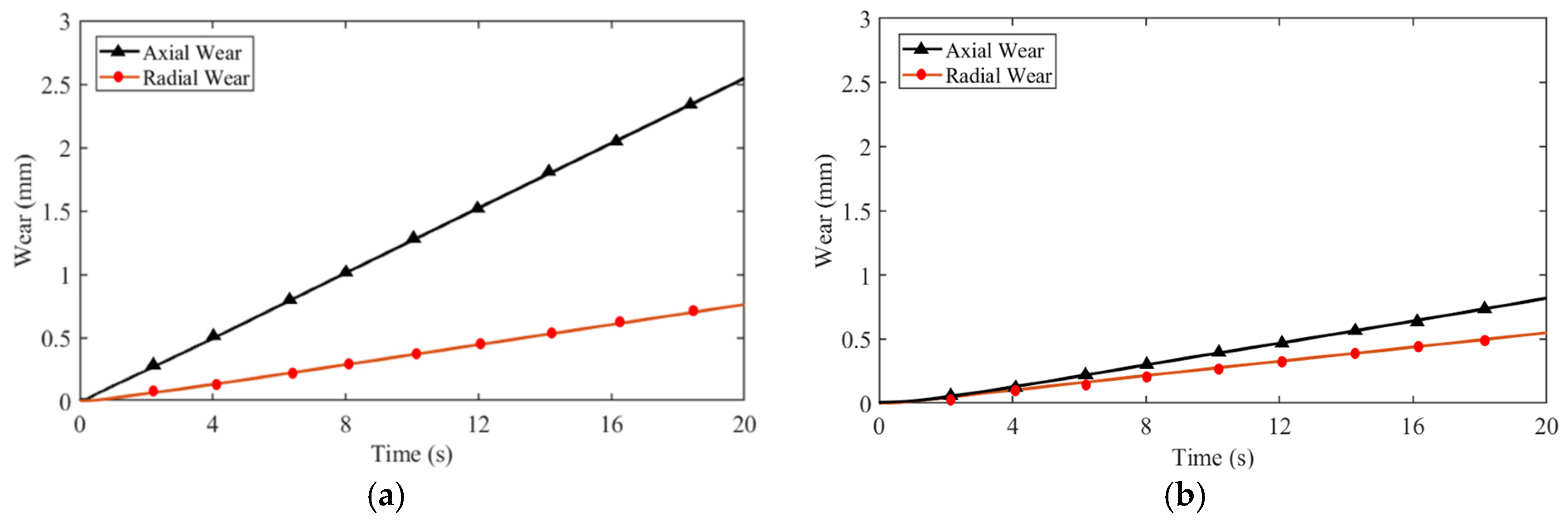

Figure 12 presents a comparison of wear on the contact surface with and without the permanent magnet bearings.

The simulation results demonstrate a substantial reduction in wear on the contact surfaces after the installation of permanent magnet bearings. Specifically, the wear on the axial contact surface was reduced by approximately 70% and the radial contact surface wear was diminished by about 26%. This indicates that the use of permanent magnet bearings significantly reduces the direct contact between the friction pairs by providing non-contact support, thereby minimizing frictional forces and wear. The reduction in wear contributes to the extended lifespan of the bearing system and improves its overall reliability. The non-contact support also helps in maintaining the integrity of the bearing materials, reducing the frequency of maintenance and its associated costs.

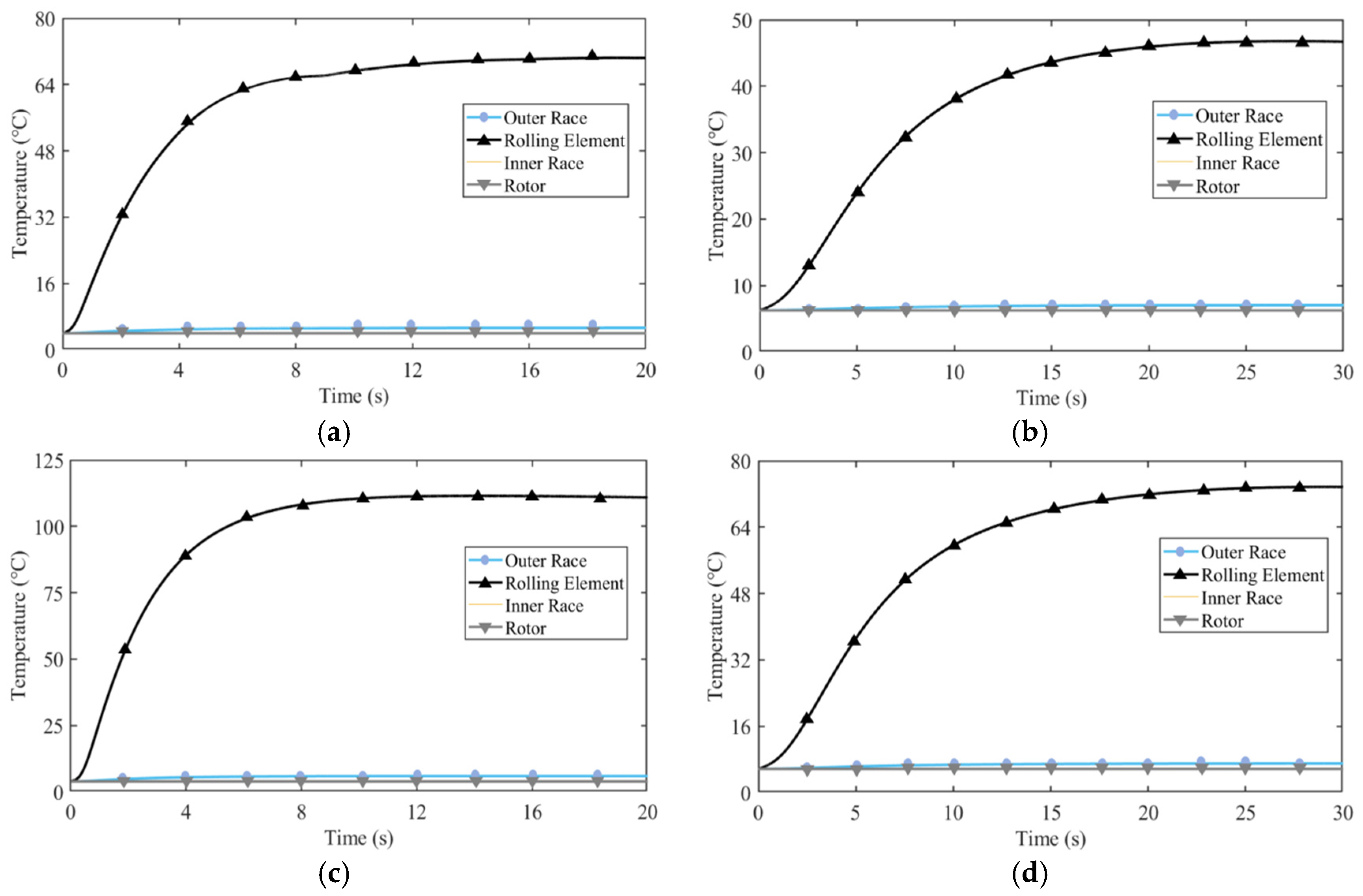

In addition to the wear analysis, the thermal behavior of the system during operation is also evaluated. A comparison of the temperature distribution within the system, both with and without permanent magnet bearings, is conducted to understand the influence of the bearings on the system’s thermal performance. This comparison is crucial because temperature rise in the system can affect material properties, lubricating conditions, and the overall stability of the bearings. The simulation results, shown in

Figure 13, highlight the temperature rise in the system at two different rotational speeds: 8000 rpm and 4000 r/min.

The temperature comparison demonstrates that after installing the permanent magnet axial protective bearing, the maximum temperature of the system drops from 70 °C to 47 °C, when it drops at 4000 r/min; at 8000 rpm, the maximum temperature of the system drops from 109 °C to 74 °C. It shows that permanent magnet bearings significantly improve the thermal state of the system by reducing friction heat generation.

Comprehensive analysis reveals that the permanent magnet bearing system designed in this paper can effectively share the axial and radial loads acting on the rolling protection bearing during the rotor drop through non-contact support, significantly reduce the contact force and wear degree, and effectively suppress the temperature rise in the system. This structure has shown good results in improving the bearing stress state, prolonging the service life, and improving the thermal stability of the system, providing a reliable guarantee for the safe operation of the FESS under drop conditions.

4.3. Fretting Friction Experiment on Line Contact of Permanent Magnet System

While simulations verify the bearing’s unloading and thermal suppression capabilities, the real contact tribological behavior of the permanent magnet material requires experimental validation. To this end, linear contact fretting tests were conducted [

45] to explore the friction and wear characteristics of the N42SH permanent magnet paired with the rotor material 40CrNiMoA and to evaluate their impact on bearing performance. In order to directly study the intrinsic friction characteristics of permanent magnet pairs, all fretting friction experiments were carried out under dry contact conditions to reveal the intrinsic wear mechanism of N42SH and 40CrNiMoA under controllable parameters. The core of this research is to realize non-contact magnetic unloading through Halbach permanent magnet bearings, aiming at reducing the dependence on contact lubrication. The temperature-varying friction data obtained from the experiment can provide a reference for the lubrication selection of the actual system under high-temperature conditions. By systematically varying load, frequency, and temperature, the evolution of the friction coefficient and the surface wear morphology were studied. This aims to reveal the underlying tribological mechanisms and provide an experimental basis for friction control, performance optimization, and life prediction of the axial protective bearing in operation.

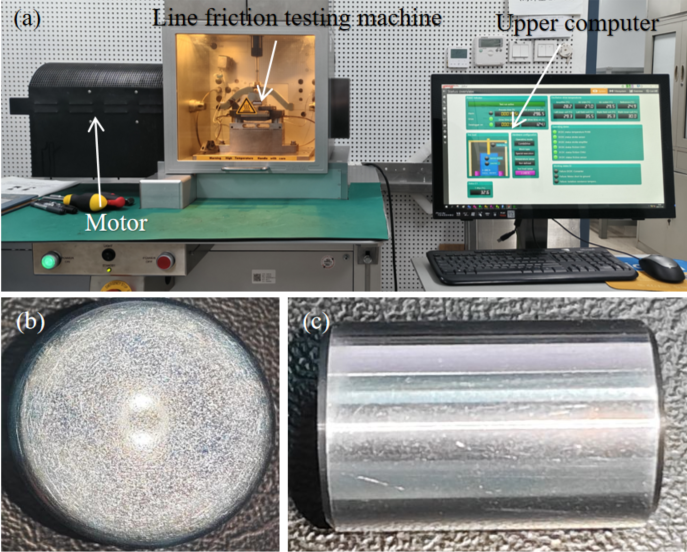

4.3.1. Experimental Method

The friction materials used in the experiments were a disk-shaped permanent magnet (N42SH) and a cylindrical rod (40CrNiMoA), with dimensions of φ24 mm × 7.88 mm and φ15 mm × 22 mm, respectively. Linear contact fretting friction tests were conducted using an SRV-5 high-temperature friction and wear tester. The surface morphology of the worn specimens was subsequently observed with a GeminiSEM-300 scanning electron microscope (SEM). The experimental setup and the samples are shown in

Figure 14.

The parameters of each experimental protocol are shown in the following

Table 3.

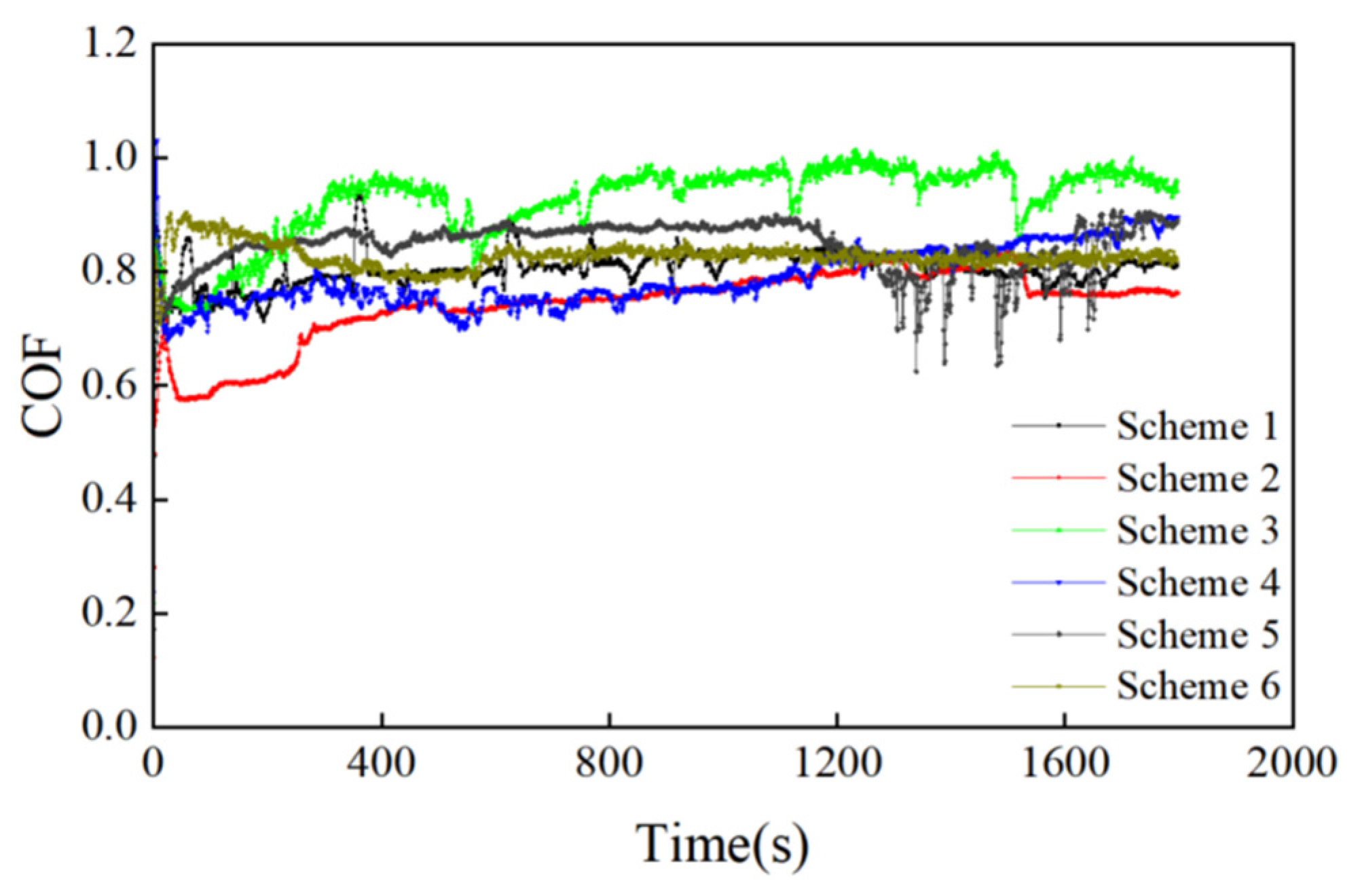

4.3.2. Coefficient of Friction

Under different experimental conditions, the friction coefficient (COF) exhibited significant differences as shown in

Figure 15. Specifically, the friction coefficient of Experiment 1 was relatively stable overall, with an average value of about 0.78, and there was a certain fluctuation in the early stage of the experiment, reaching up to 0.93. The friction coefficient of Experiment 3 was about 0.75 at the beginning, then decreased to a low level, gradually increased, tended to be stable in the later stage, and finally remained around 0.78. The friction coefficient of Experiment 5 was low in the initial stage, gradually increased with the experiment, and finally stabilized at about 0.95, with certain fluctuations throughout the process. The friction coefficient of Experiment 7 was stable at about 0.72 at the beginning, then remained stable, and finally rose to around 0.87, with the overall change being relatively moderate. The friction coefficient of Experiment 9 was maintained at about 0.85 most of the time, but it decreased to about 0.80 in the later stage of the experiment, with obvious fluctuations. The friction coefficient of Experiment 11 was stable throughout the experiment and finally remained around 0.8.

Figure 15.

Friction curves under each scheme.

Figure 15.

Friction curves under each scheme.

By comparing the results of Experiment 1 and Experiment 5, alongside Experiment 7 and Experiment 11, it can be seen that the lower frequency helps to maintain the stability of the friction coefficient. Under the condition of low frequency, the contact state of the friction pair changes smoothly, the wear degree is relatively light, and the friction process is more stable. However, higher frequency will aggravate the dynamic change in contact surface, resulting in significant fluctuation of the friction coefficient and more frequent changes in heat accumulation effect and surface stress, thus accelerating the friction and wear process, and may induce material fatigue or surface degradation.

Comparing the results of Experiment 1 and Experiment 3, alongside Experiment 7 and Experiment 9, they show that the friction coefficient is generally lower, the corresponding friction force is smaller, and the degree of wear is lighter under low load. Low load reduces the contact stress, helps to suppress the fluctuation of the friction coefficient, and makes the friction process tend towards being stable. In contrast, high load will increase contact stress, which in turn increases the friction coefficient and friction force and aggravates wear. Under this condition, the friction coefficient usually fluctuates greatly, and it is easy to cause obvious heat accumulation and surface wear.

By analyzing the comparison results of Experiment 1 and Experiment 7, Experiment 3 and Experiment 9, and Experiment 5 and Experiment 11, it is found that the friction coefficient is generally stable at normal temperatures and is suitable for conventional working conditions. Lower temperature is beneficial to maintain the hardness and structural stability of the material, but it may lead to a decrease in lubrication performance, especially under higher load or frequency conditions, wherein the friction coefficient may increase and the wear will increase accordingly. Moderate temperature rise helps to improve the lubrication state and reduce the fluctuation of the friction coefficient, especially under high-load or high-frequency conditions, which can effectively reduce the change amplitude of friction force, thus reducing surface wear. However, excessive temperature may lead to softening or thermal expansion of the material, thus affecting its tribological properties and structural stability.

Low load and appropriate temperature are conducive to maintaining the stability of the friction coefficient and reducing wear; although high frequency and high load help to improve the bearing capacity of the system, they will also aggravate the fluctuation of the friction coefficient, leading to more significant wear and material degradation; reasonable temperature control can improve lubrication conditions and friction stability, but a temperature that is too high will adversely affect the material properties.

4.3.3. SEM Analysis of Wear Surface of Friction Materials

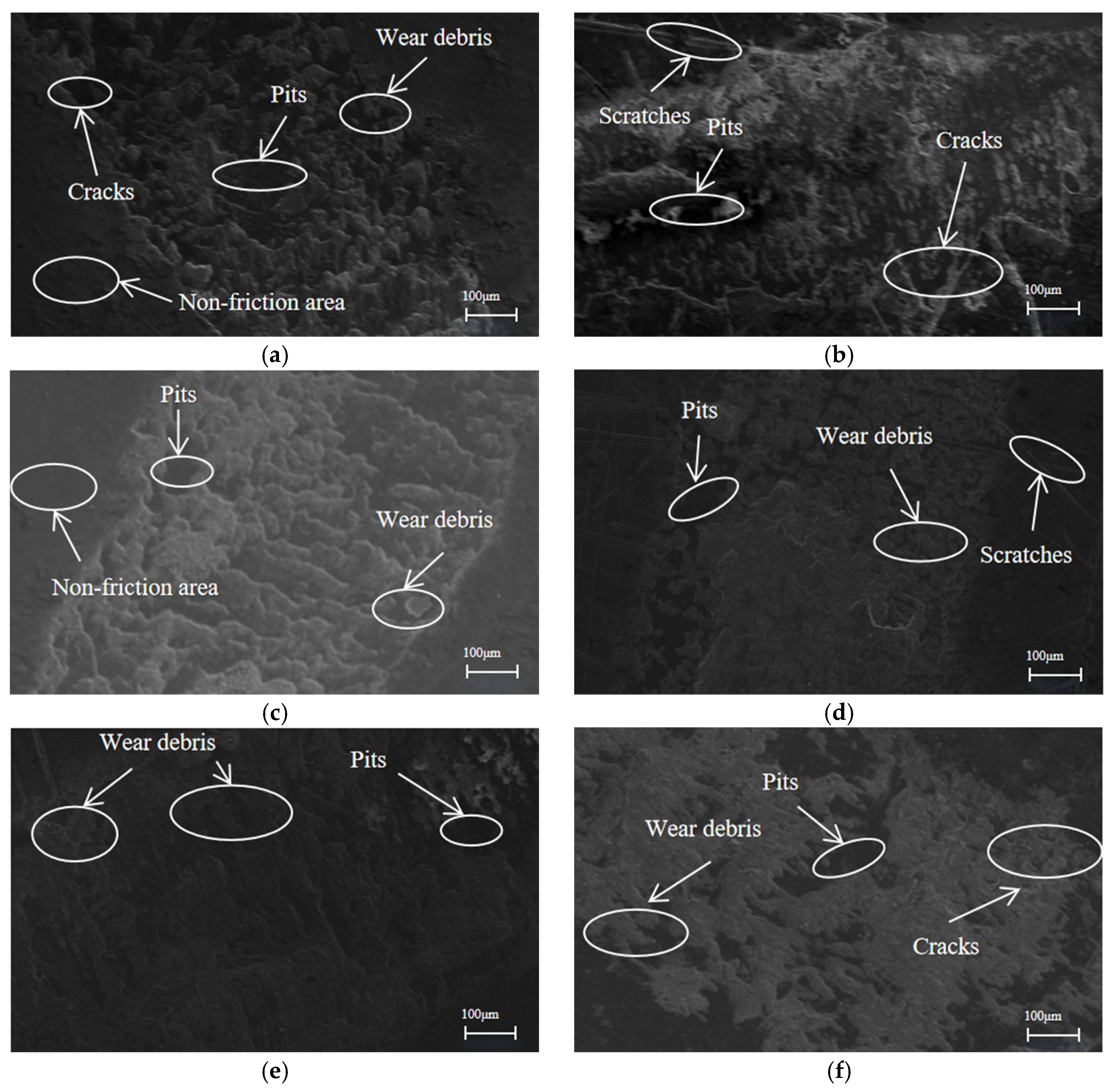

In order to analyze the friction behavior and wear mechanism of permanent magnet material N42SH, the wear surface was observed by scanning electron microscope (SEM).

Figure 16 shows the SEM morphology of the material surface under different experimental conditions.

Under different experimental conditions, the micro-morphology of the wear surface of each sample showed obvious differences. In

Figure 16a, the surface wear was relatively uniform and the whole surface was relatively flat. The distribution of fine abrasive particles, pits, and micro-cracks could be seen and the degree of wear was light, indicating that the material was relatively stable in the friction process. This kind of morphology mostly corresponded with low-load and low-frequency conditions, with a small friction force and no significant surface plastic deformation. In

Figure 16b, serious wear characteristics were shown, with an irregular surface, local spalling, and some wear debris attached, which may have been due to excessive local temperature rise or excessive load during friction. This morphology was mostly related to a higher load or frequency and the friction heat and stress concentration led to the peeling of the material surface. In

Figure 16c, obvious scratches and micro-cracks could be seen on the surface, with overall roughness, serious local wear, and plastic deformation marks. This may have been the result of the combined action of higher load and long-term friction and the larger stress and friction aggravated the surface damage. In

Figure 16d, the wear morphology was relatively flat, the surface was relatively smooth, and only fine abrasive particles and superficial scratches were distributed, reflecting that the stress was small and the wear was slight during the friction process. This kind of morphology mostly appeared under the condition of a low friction coefficient and small load and the surface damage was uniform and mild. In

Figure 16e, large cracks and local spalling can be seen, with deep wear marks and surface granulation, which may have been related to larger friction force. This morphology was common in high-load or long-term friction conditions, and high stress led to plastic flow and surface failure of materials. In

Figure 16f, the surface was relatively smooth, with slight wear, shallow and uniform wear marks, no obvious plastic deformation, and only microscopic fine lines, which may have been fine scratches formed during friction. This kind of morphology mostly corresponded to low load, low frequency, and stable friction environment, and the material surface presented uniform and stable wear characteristics.

In friction experiments, load is the main factor affecting surface morphology and material properties. Higher load will significantly increase friction and contact stress, leading to aggravated wear, crack initiation and material fatigue, and will then seriously affect the long-term service performance of materials. Appropriate temperature can improve lubrication conditions, reduce the friction coefficient and slow down wear, but a temperature that is too high will cause material softening and surface degradation, damaging its structural stability and durability. In contrast, the influence of frequency on surface topography is relatively limited; although an increase in frequency will cause slight fluctuations in the friction surface state, its effect on the stability of the friction process and material properties is relatively minor. Generally speaking, load is the most critical influencing factor, followed by temperature, and frequency has the smallest influence.

Based on the above conclusions, the following measures are suggested in actual operation for the axial permanent magnet protective bearing system: First, the contact stress between the rotor and the permanent magnet should be controlled to improve the process performance of the rotor and the permanent magnet and avoid damage to the permanent magnet caused by excessive assembly eccentric force; Secondly, it is advisable to control the working temperature of the system below 70 °C to maintain good lubrication and reduce friction and wear; Finally, although the frequency has little influence on the friction behavior, the centrifugal force increases with the increase in frequency, so it is still necessary to pay attention to the potential influence of limit frequency on the dynamic behavior and stability of permanent magnet systems.