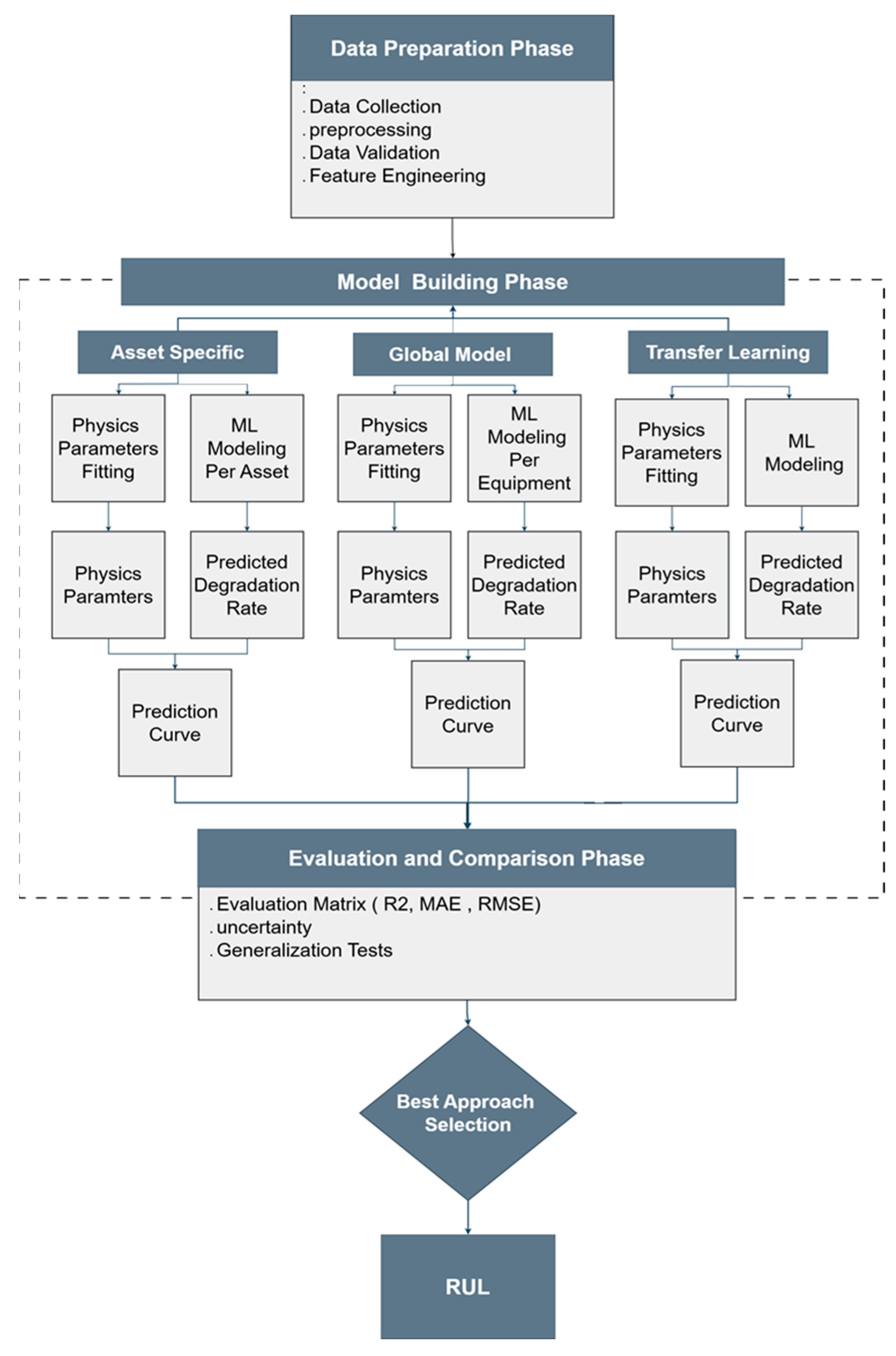

This section presents the outcomes of the proposed framework in three progressive levels: parameter-level model performance, equipment-level generalization, and comparative evaluation across modeling strategies. This hierarchical structure reflects how the models capture degradation behavior from individual oil parameters up to equipment-specific domains.

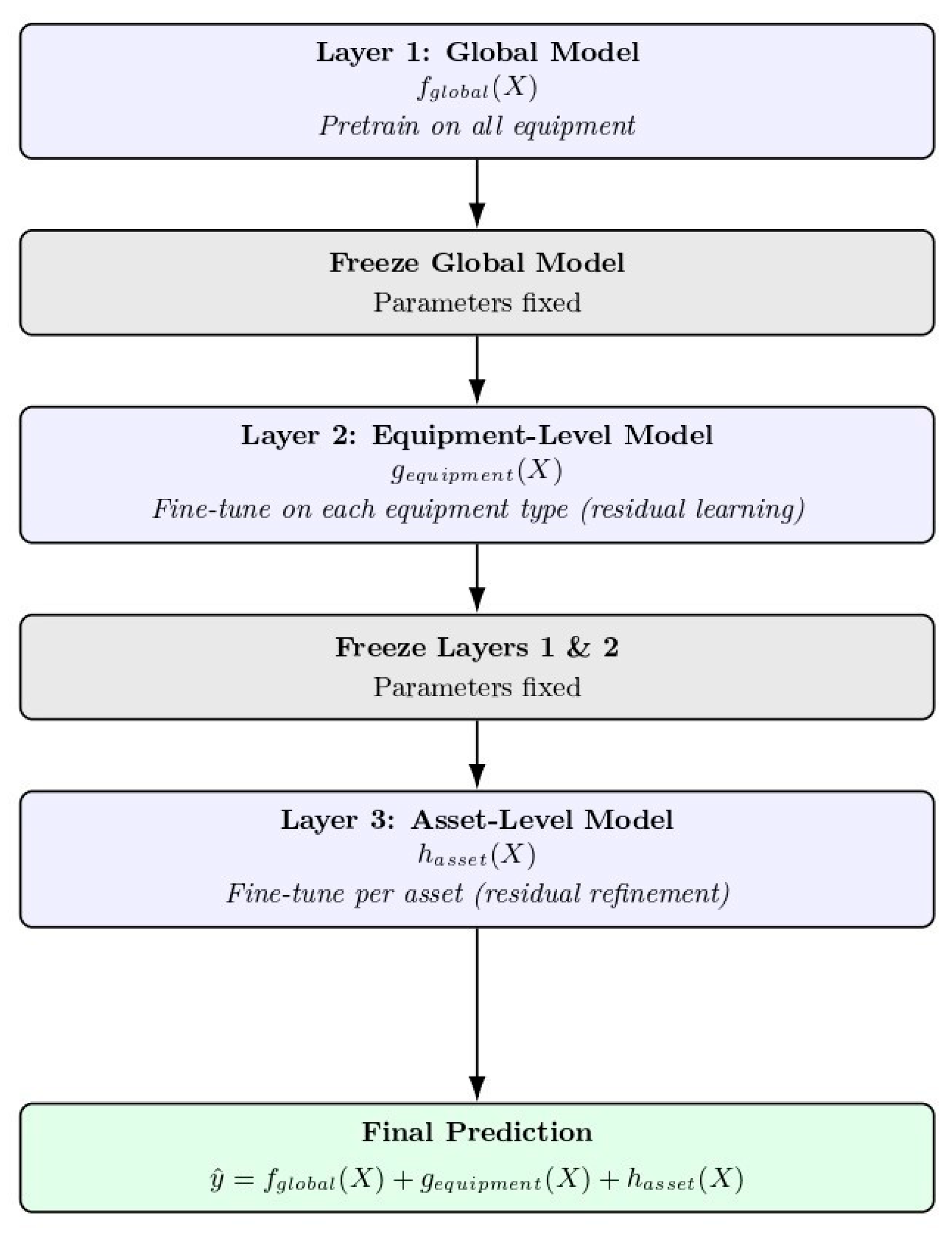

4.1. Correlation Analysis Across Equipment Types

To investigate the interdependence of wear metals, contaminants, additive indictors, and degradation parameters across the fleet, correlation heatmaps were generated for each equipment category: dozers, dump trucks, shovels, and wheel loaders (

Figure 3). Each matrix identifies whether variables such as Fe, PQ Index, soot, viscosity, TBN, and oxidation exhibit systematic relationships that can be used to support RUL prediction.

Across all equipment types, a high correlation between PQ Index and Fe is consistently observed, confirming that PQ Index reliably tracks ferrous wear progression. This supports its role as an indicator of mechanical deterioration rather than purely chemical degradation. Viscosity, oxidation, and TBN show weaker correlations with wear metals, reflecting the multi-mechanism nature of lubricant aging, where chemical degradation and mechanical wear evolve partly independently.

These patterns justify the current modeling approach where RUL is not predicted from a single dominant indicator but from the combined evolution of chemically driven (oxidation, viscosity, TBN/TAN) and mechanically driven (PQ, Fe, Cu, Pb) degradation parameters. The multi-indicator correlations further reinforce the need for the hierarchical transfer learning framework, which can accommodate heterogeneous degradation influences across different asset categories.

4.2. Parameter-Level Model Performance

This subsection evaluates the ability of the developed models to reproduce the laboratory-measured lubricant parameters that represent wear, contamination, and additive depletion. The R2 coefficient of determination was used as the main indicator of predictive accuracy, supported by visual assessment of the predicted versus actual distributions.

In interpreting the parameter predictions, it is important to note that the laboratory control limits define the acceptable variation range for each oil property. These limits are derived from the company condition monitoring thresholds and act as the practical boundaries within which the models should reproduce measured values. A prediction that stays within these limits, even with minor deviation from the exact laboratory point, is still considered operationally valid. Hence, the model accuracy was judged not only by statistical fit but also by how often the predicted values remained within the established control limits.

Table 5 summarizes the best-performing generalized models across all measured parameters. Gradient Boosting and Extra Trees algorithms consistently achieved the highest predictive accuracy, particularly for Magnesium (R

2 = 0.946) and Calcium (R

2 = 0.902), both linked to additive depletion and detergent retention. The strong performance in these parameters suggests that the models effectively captured the gradual decline typical of base-additive consumption processes. In contrast, Sodium and Silicon showed lower R

2 values due to higher variability in field measurements and contamination effects rather than algorithmic limitations.

While the model shows weak predictive behavior for Sodium and Water, this limitation is both expected and operationally acceptable. These parameters typically remain below detection thresholds for most samples and increase only during abnormal events such as coolant leakage, seal failure, or moisture ingress. Their statistical variance is therefore driven more by measurement noise than progressive degradation chemistry, making them unsuitable predictors for continuous RUL estimation. Rather than a deficiency of the model, this reflects the physical nature of these indicators, they serve as binary contamination alerts, not gradual wear markers. Accordingly, their low R2 does not impact the model’s ability to estimate degradation trends or remaining oil life, and their monitoring should remain threshold-triggered rather than regression-based.

The R2 values for several parameters fall below 0.75, which is common in real-world oil-analysis datasets. Field samples are inherently influenced by operational variability, fluctuating load profiles, intermittent contamination events, and laboratory measurement noise. These factors collectively limit the maximum achievable coefficient of determination, even for well-constructed models. Therefore, moderate R2 values should not be interpreted as being indicative of poor predictive performance; rather, they reflect the true complexity and noise inherent in practical industrial environments.

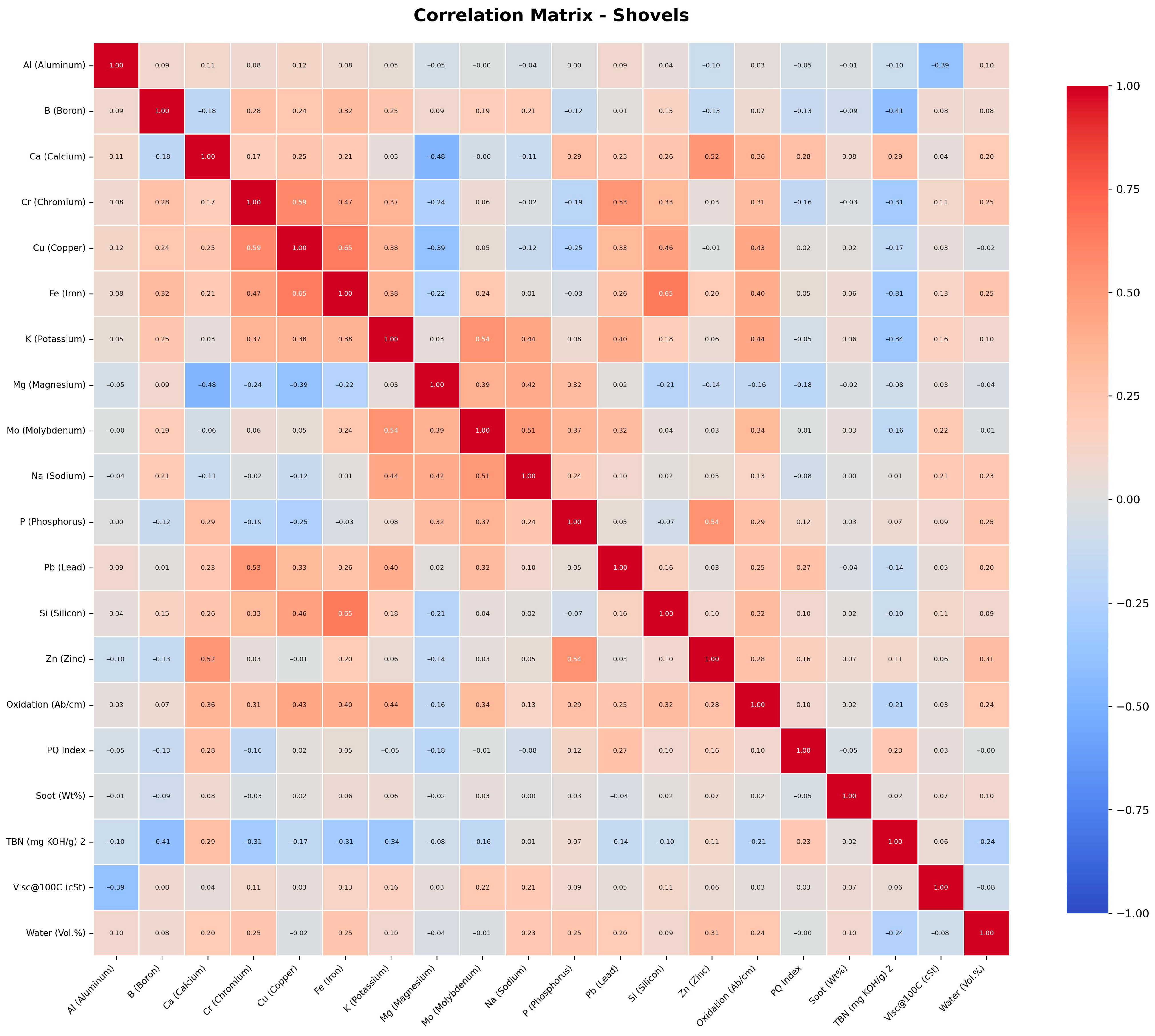

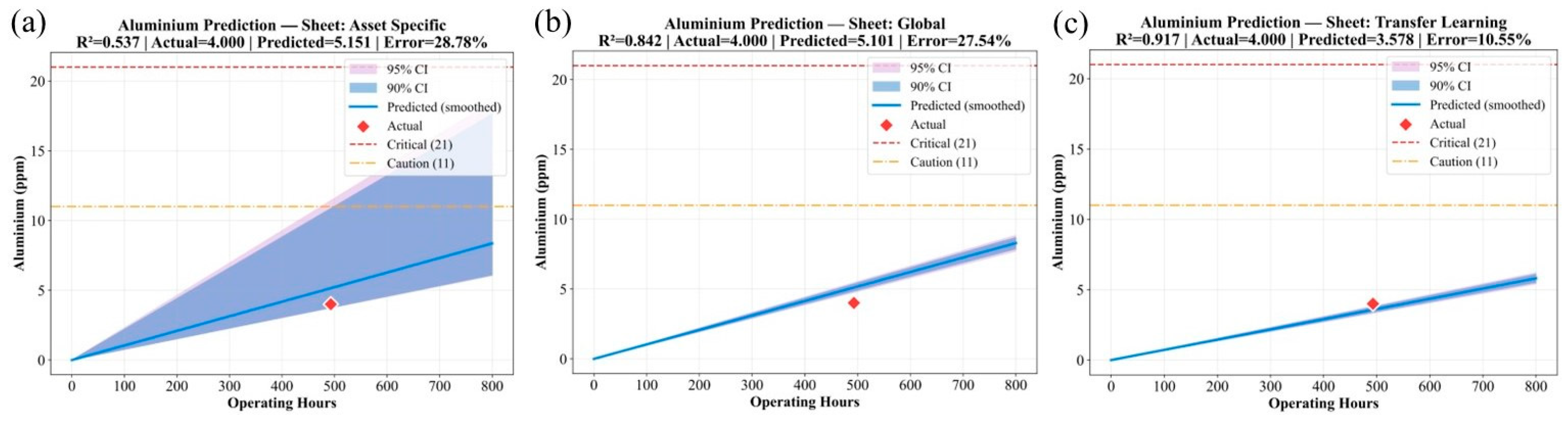

Importantly, the Transfer Learning model consistently outperforms other configurations, exhibiting lower uncertainty and more stable predictions across different engines. This demonstrates that the model effectively captures the underlying degradation behavior despite the unavoidable noise in field data, highlighting the robustness and practical value of the proposed framework.

Table 6 compares the predictive accuracy of Asset-Specific, Global Model, and transfer learning models for key lubricant parameters representing wear (Fe), contamination (Soot), and additive depletion (P, TBN, Mg, Al).

In each case, transfer learning achieved the highest R2. Furthermore, it produced the lowest prediction errors, indicating that the incorporation of generalized cross-equipment knowledge provides a stronger starting point for learning. By fine-tuning this prior knowledge to the operating conditions of a specific engine, the TL model captures degradation patterns more effectively than models trained from scratch. This demonstrates that transfer learning not only improves statistical accuracy but also enhances the robustness and reliability of predictions across different degradation pathways.

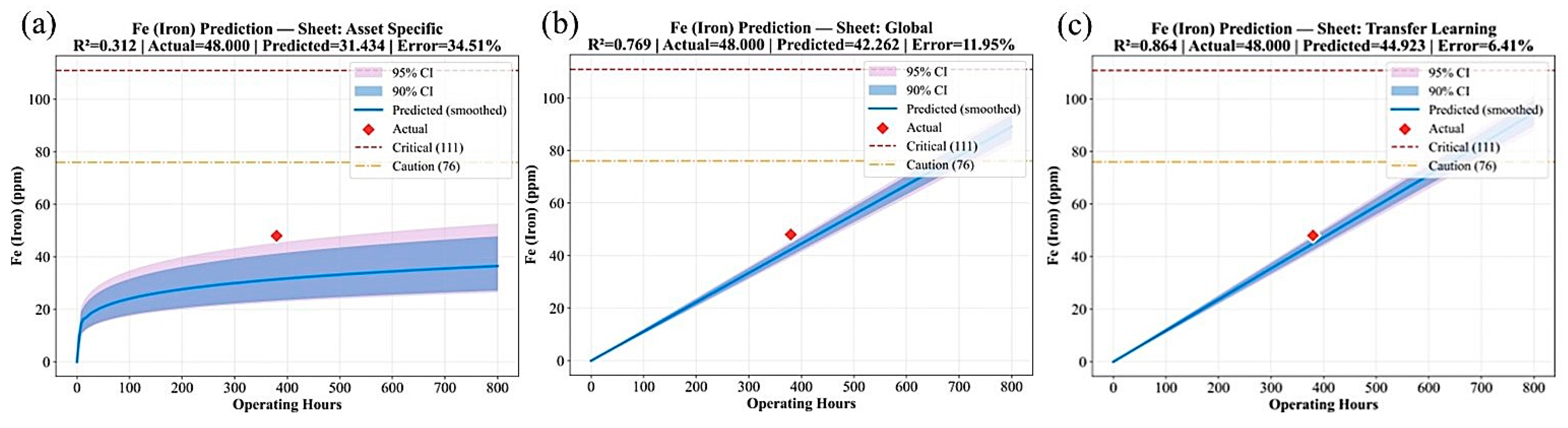

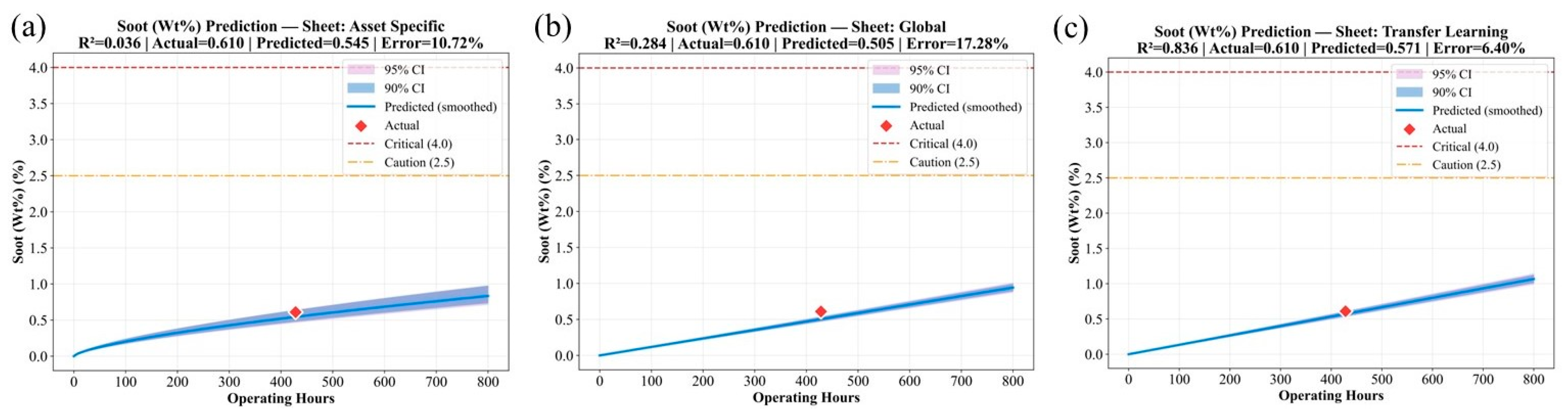

The superior performance of the TL model in capturing the trends of these accumulation-type parameters is visually confirmed in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. These figures illustrate how the TL-predicted trajectories for Aluminum, Iron, and Soot align closely with the measured laboratory data, effectively capturing both linear and nonlinear growth behaviors, unlike the AS and GM models either deviate substantially or over-smooth the trends due to limited exposure to broader degradation characteristics.

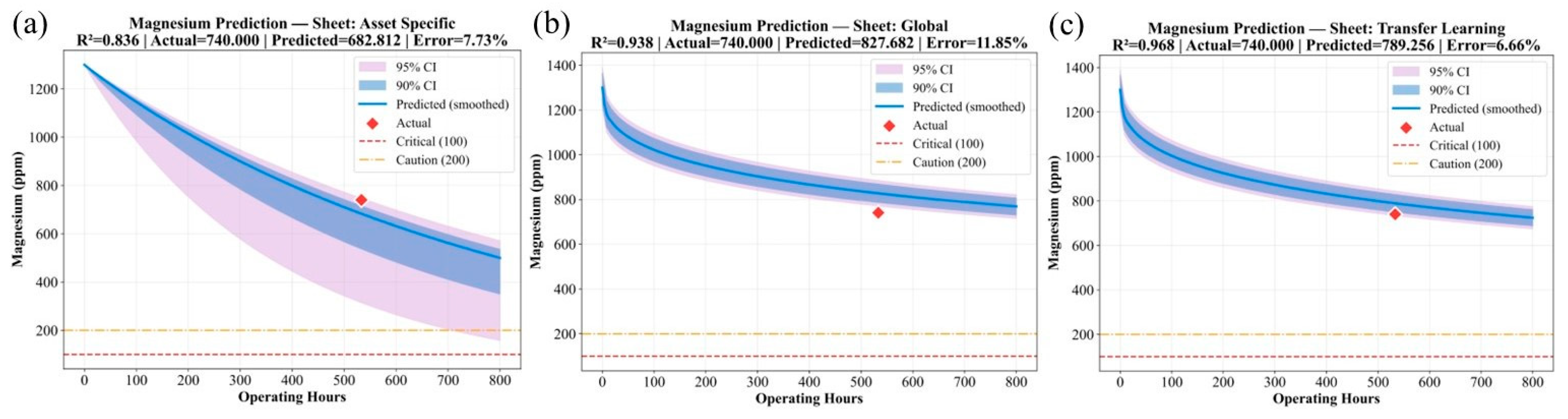

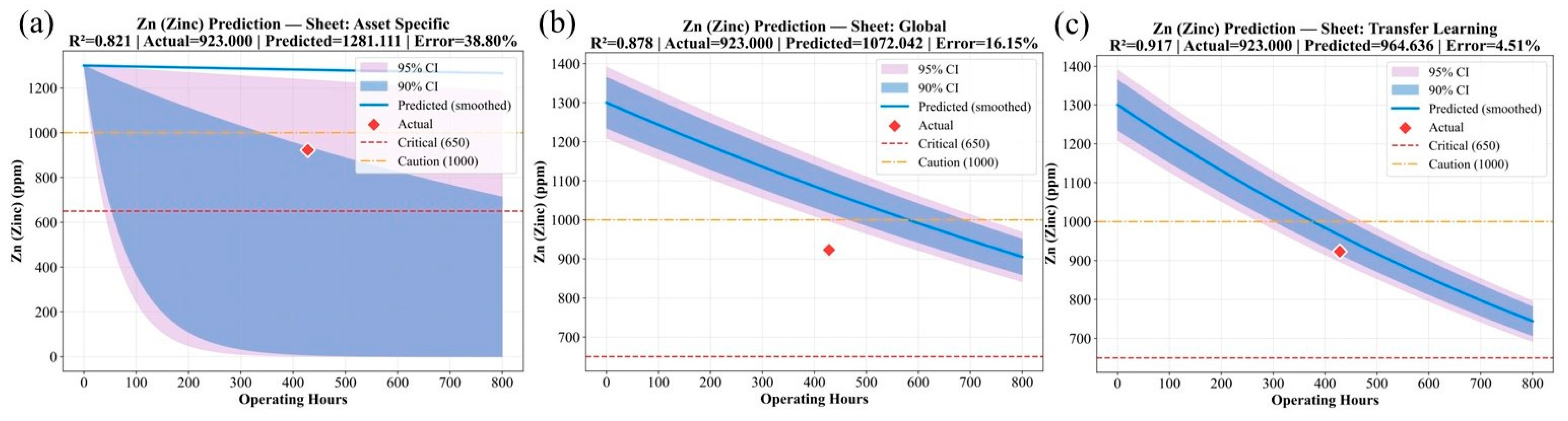

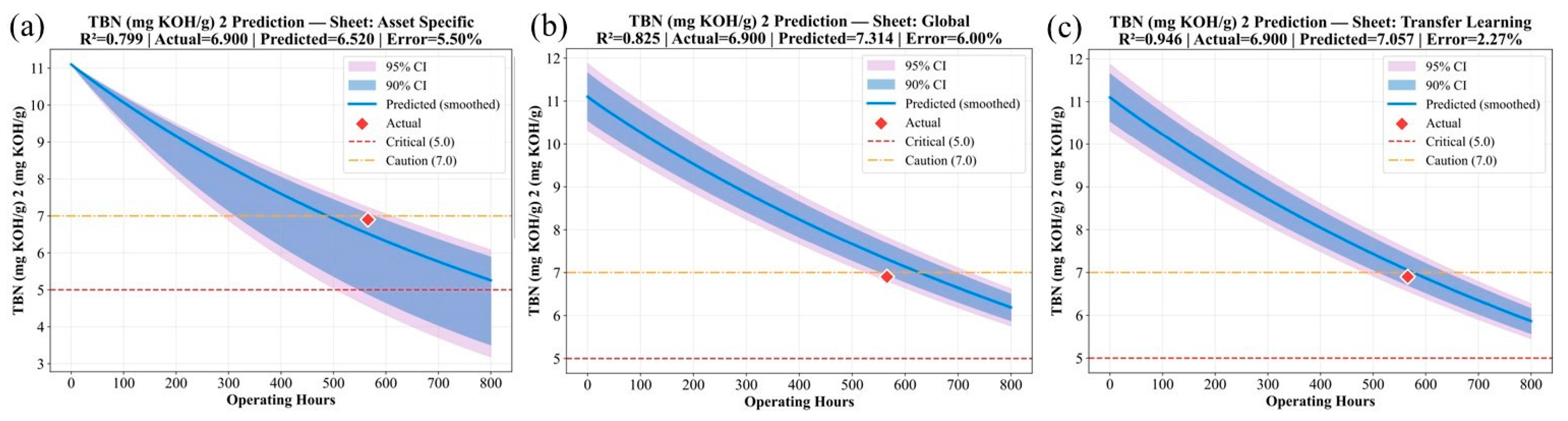

A similar advantage is observed for depletion-type parameters.

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 illustrate that the TL model accurately tracks the decline of Magnesium, Zinc, and TBN. Its predictions follow the true degradation pathway while maintaining physical plausibility and staying within operational control limits. The AS and GM models, on the other hand, exhibit higher variability, less stability, and larger prediction errors because they lack the benefit of prior generalized representations.

Overall, the clear improvement shown by TL across both accumulation and depletion behaviors highlights the importance of reusing learned degradation dynamics and refining them to the specific engine environment.

The consistent performance improvement across parameters and equipment confirms that oil degradation mechanisms. Particularly oxidation, metallic wear, and additive depletion exhibit transferable kinetic signatures. Once a Global pre-trained model is established, new assets can be efficiently adapted through fine-tuning, enabling scalable and reliable predictive maintenance deployment.

Nonetheless, few parameters such as Sodium, Water, and Silicon, yielded very low or slightly negative R2 values. This does not indicate poor model performance but rather reflects the intrinsic characteristics of these variables. Their concentrations remain close to zero for most samples and increase only under rare contamination or abnormal operating conditions. Consequently, the available data for these parameters show minimal true variation, and any observed fluctuations are often dominated by measurement noise rather than meaningful degradation trends. Under such low signal-to-noise conditions, predictive correlation becomes statistically unstable, producing near-zero or negative R2 values.

These findings suggest that while such parameters provide limited predictive value, those exhibiting stronger and more consistent dynamic behavior, such as Fe, Cu, Mg, and Oxidation, are the principal contributors to accurate oil degradation modeling and Remaining Useful Life (RUL) estimation.

Across these parameters, the models reproduced both linear and nonlinear degradation tendencies with high fidelity. Aluminum and Iron increased progressively with usage, whereas Soot showed exponential-like behavior. The predicted values aligned closely with measured laboratory data, confirming that the models successfully captured physical degradation patterns.

Furthermore, predicted trends remained within realistic operational bounds, showing no artificial extrapolation or saturation outside the observed control limits. These limits, derived from the upper and lower quantiles of historical laboratory data, represent the practical thresholds beyond which oil is considered degraded or contaminated. The model outputs stayed consistently inside these intervals, confirming that the learning process respected the physical range of each parameter rather than generating implausible values. This strengthens confidence that the predictive behavior aligns with real-world maintenance control criteria. The parameter-level assessment establishes that the developed models can effectively capture the degradation behavior of individual oil properties.

The next step is to evaluate whether these learned relationships can generalize across different engine types, where operating conditions, loading cycles, and maintenance intervals vary substantially.

4.4. Comparative Evaluation of Modeling Strategies

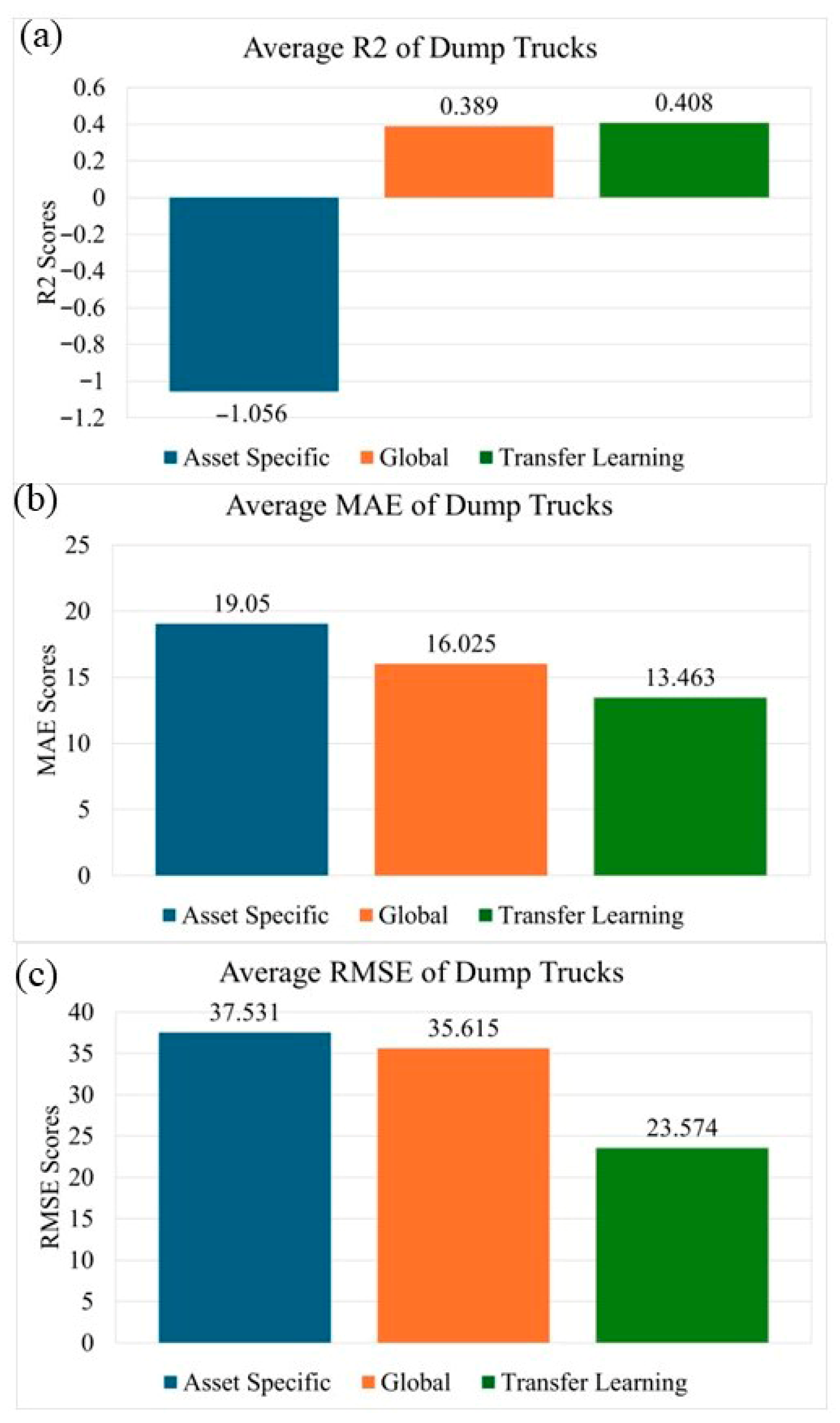

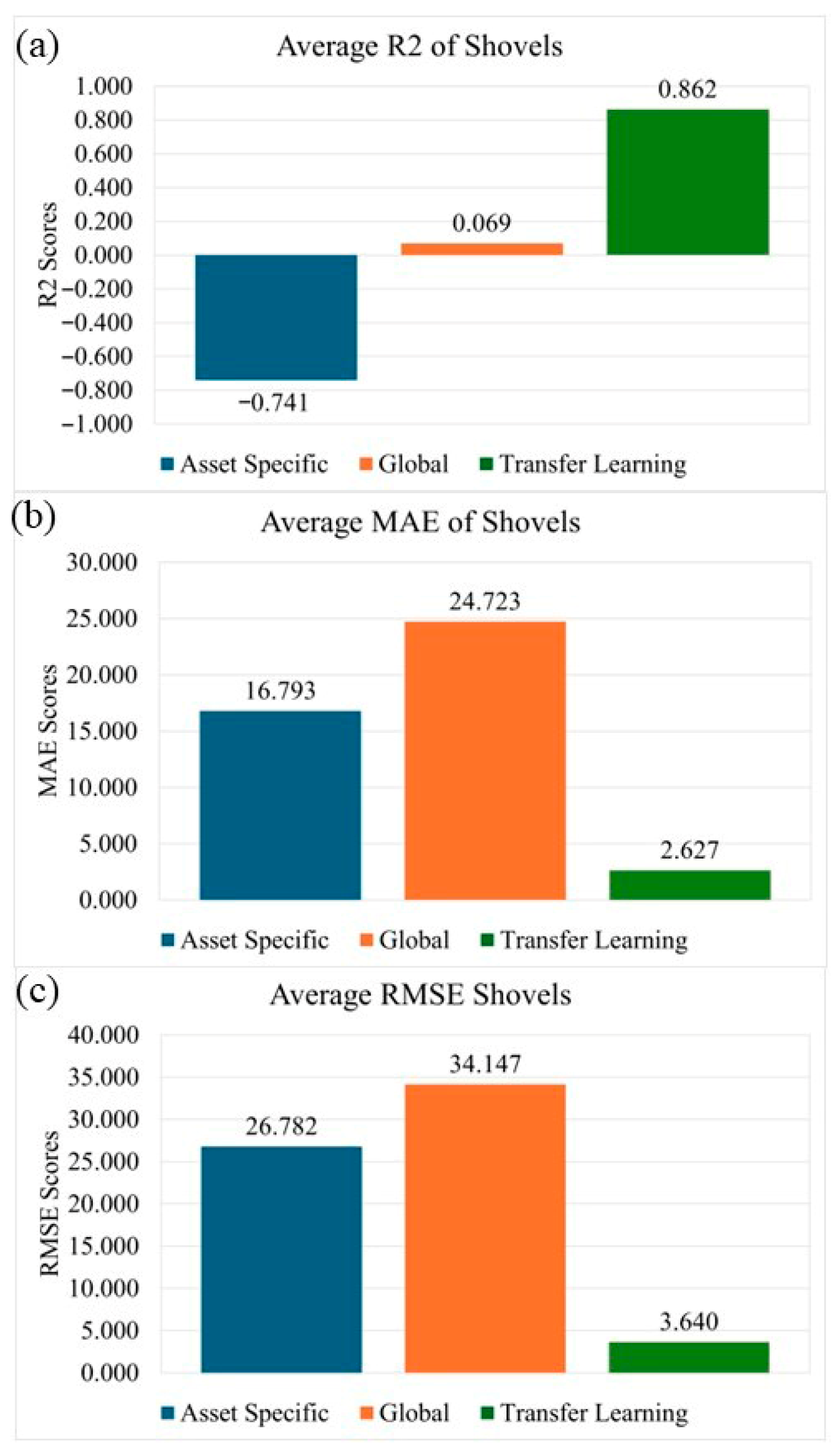

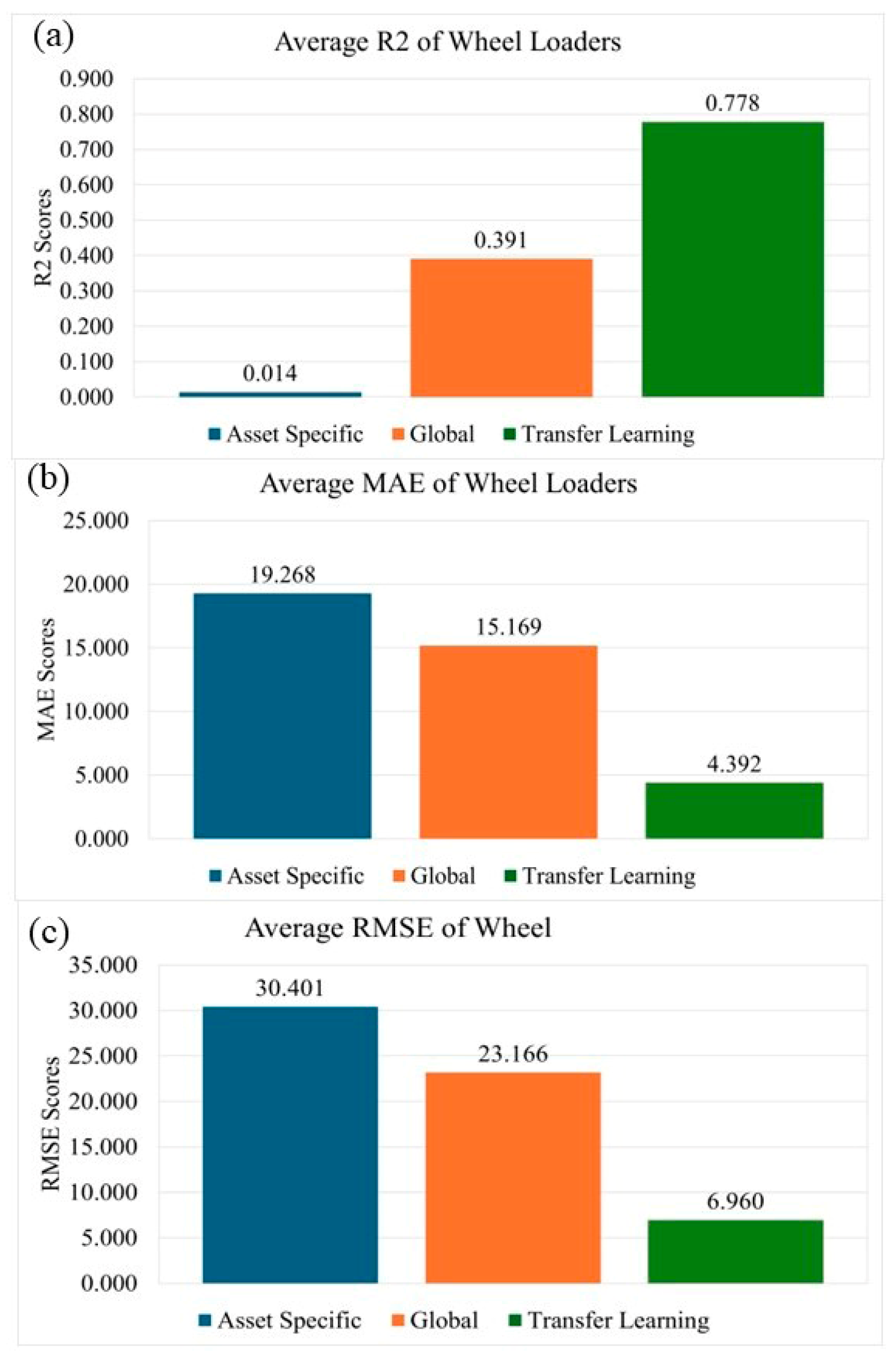

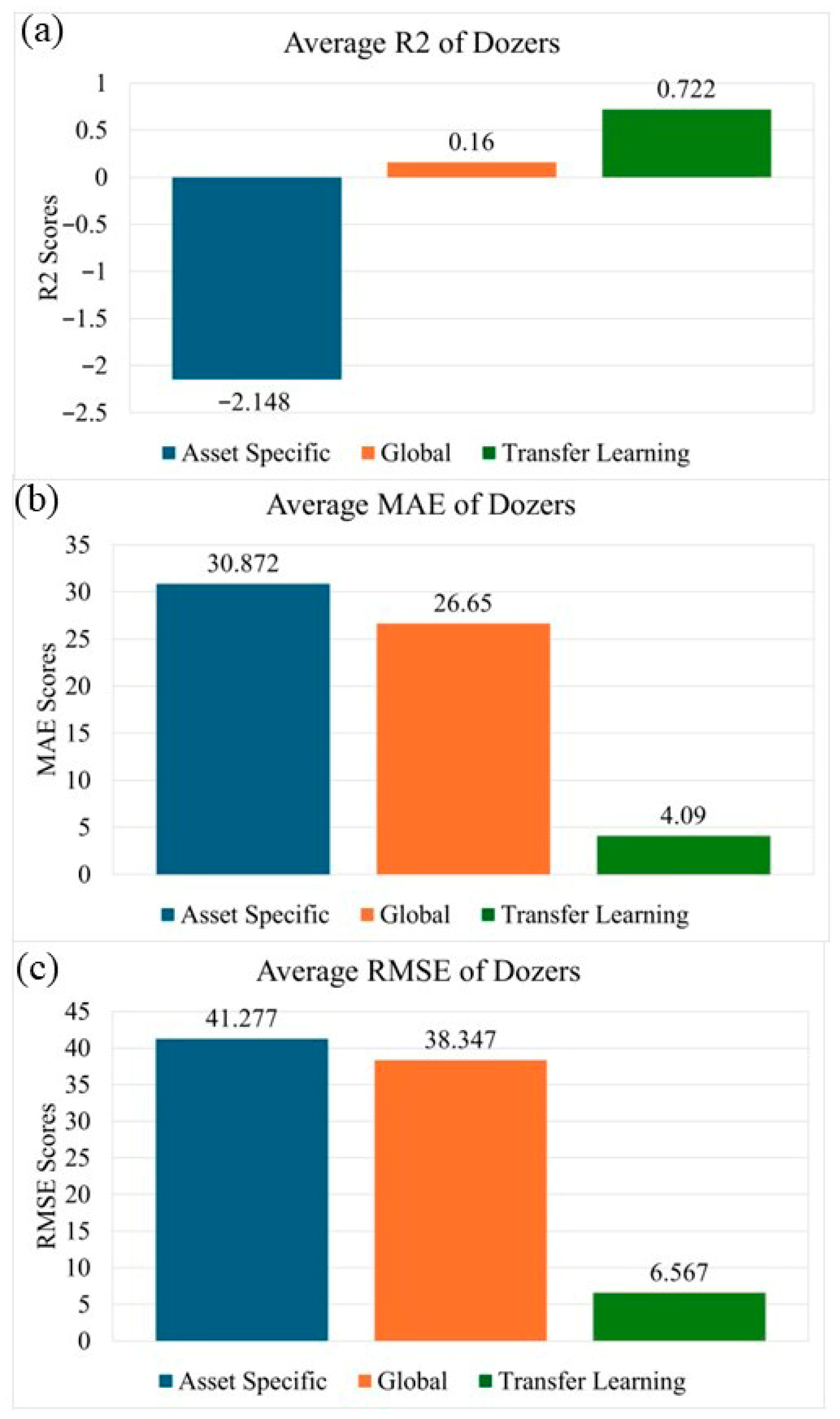

The comparative assessment across the three modeling configurations—Asset-Specific (AS), Global Model (GM), and Transfer Learning (TL)—provides an integrated understanding of predictive stability, generalization capacity, and robustness under heterogeneous operating environments. As summarized in

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 and

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12, the Transfer Learning (TL) approach consistently achieved the highest explanatory performance and the lowest prediction errors across most equipment classes and parameters.

The aggregated results in

Table 15 confirm the superior generalization capability of the Transfer Learning approach. While the Global Model achieved moderate explanatory power, its prediction errors remained comparatively high and uncertain. In contrast, the TL configuration delivered a threefold reduction in RMSE and a confidence interval width nearly half that of the GM model, highlighting both higher predictive precision and lower output variance across the full dataset.

The TL model consistently outperformed both the Asset Specific and Global configurations because it inherits generalized degradation knowledge learned at fleet level while also fine tuning to the operating profile of each asset. This enables TL to avoid overfitting, which is common in Asset Specific models with limited samples and prevents underfitting that often occurs in Global models where engine behavior is averaged. Since oil degradation follows shared thermochemical patterns such as oxidation, additive depletion, and soot growth, these kinetics are transferable across machines using the same lubricant. TL leverages this by learning the global degradation structure first, then adapting it locally with minimal calibration. As a result, it achieves higher R2, lower uncertainty and better generalization across diverse field conditions, demonstrating a structural learning advantage rather than a simple numerical improvement.

To provide clear quantitative evidence of the model’s behavior on individual assets,

Table 16 presents the predicted RUL, caution thresholds, and alert points for one representative sample from each asset category, mentioned earlier in

Table 2. It is crucial to note that the framework assesses two independent states: (a) machine state which is evaluated via wear-related parameters (e.g., Fe, Cu, Al) and (b) oil state evaluated via oil-specific indicators (e.g., TBN, additives, viscosity). The failure logic is applied separately to each state. End-of-life is declared either when: (a) any single parameter reaches its alert threshold, or (b) two distinct parameters reach at least their caution thresholds. The “1st Caution,” “2nd Caution,” and “Alert & Time” columns in

Table 16 report the chronological order in which different parameters are predicted to cross these limits, identifying the key indicators driving the risk for each asset.

The results in

Table 16 illustrate distinct degradation patterns and the application of the logic described above. In case of Dump Truck (DA-2), the oil is already at end-of-life (RUL = 0 h) because Molybdenum (Mo) has reached its alert threshold. The machine itself remains healthy. For the Shovel (SA-1), the machine is predicted to fail at 282 h; however, it did not reach an alert level by any of the two indicators that reached the threshold levels. On the other hand, the oil reaches end-of-life earlier at 177 h (triggered by Si alert). This suggests that although the machine is currently healthy, an oil change is the imminent maintenance need. Moving to the Wheel Loader (WF-8), the oil is predicted to reach end-of-life in 121 h, triggered when TBN reaches its caution threshold as the second indicator (following an earlier Zn caution). The machine shows a caution for Al but has a long RUL (800 h). The results of the Dozer (DOC-1) indicate that multiple oil parameters are in alert, mandating immediate oil replacement (RUL = 0 h). Concurrently, the machine is projected to fail due to wear (Fe) in 419 h, indicating a major maintenance event should follow.

This quantitative breakdown demonstrates that each asset follows a unique degradation trajectory governed by different combinations of chemical, wear, and contamination indicators. These case-specific patterns underscore the necessity of the proposed multi-indicator framework. Reliable RUL estimation cannot depend on a single parameter; instead, it requires the integrated assessment enabled by the “second-indicator” failure rule, which accurately reflects the complex, multi-faceted nature of oil degradation in real-world operating conditions.

4.4.1. Overall Predictive Strength and Bias Trends

The AS models, trained exclusively on individual asset histories, exhibited strong within-sample fitting but poor generalization, frequently yielding negative or near-zero R2 values (e.g., Dump Trucks and Dozers). This behavior indicates overfitting to Asset-Specific noise and insufficient learning of transferable degradation dynamics. Conversely, GM configurations, which leveraged pooled multi-asset data, demonstrated moderate improvements in mean R2 and reduced variance but occasionally suffered from underfit-ting, particularly when asset behaviors diverged substantially due to different loading conditions or duty cycles.

TL configurations achieved the most balanced behavior. By leveraging pre-trained representations from the global domain and fine-tuning on limited Asset-Specific samples, TL reconciled the bias–variance trade-off: it preserved general degradation structure while adapting to local signal variations. This hybridization yielded the most stable and interpretable results, with average R2 values exceeding 0.7 in Shovels and Wheel Loaders, and markedly reduced error dispersion relative to both AS and GM models.

4.4.2. Error Distribution, Residual Behavior, and Uncertainty

Residual analyses revealed that AS models often exhibited multimodal and heteroscedastic patterns, consistent with overfitting and sensitivity to measurement noise. GM residuals were more uniform but displayed systematic bias at extreme degradation levels, implying limited flexibility in capturing nonlinear progression. In contrast, TL residuals were approximately Gaussian and centered near zero, indicating unbiased estimation across the degradation range. Furthermore, uncertainty quantification using bootstrap resampling (1000 replicates) showed that TL yielded the lowest coefficient of variation in predicted outputs, on average 7–10% lower than GM, confirming superior robustness under variable data regimes.

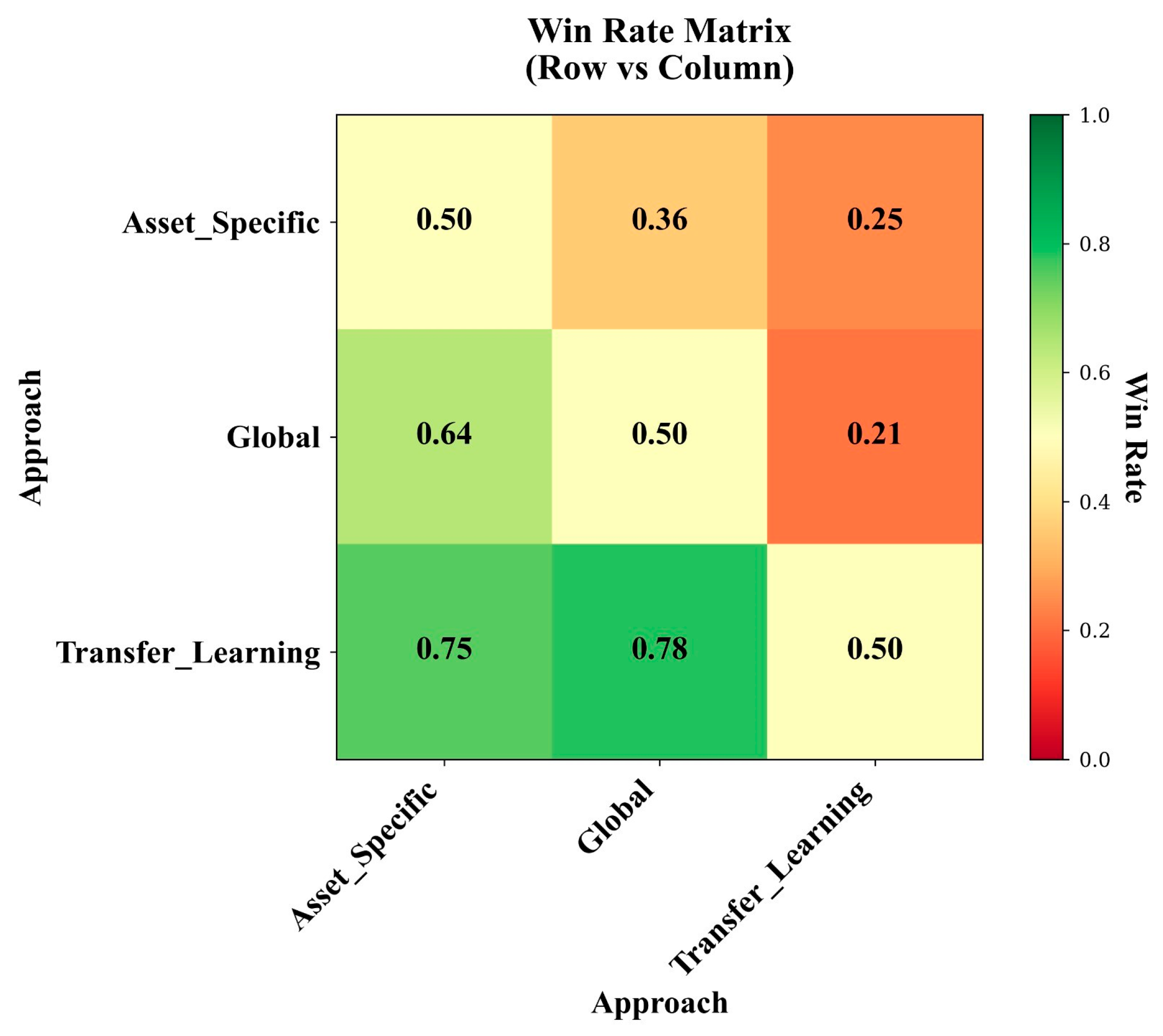

A pairwise win-rate matrix (

Figure 14) summarizes the frequency with which each model outperformed the others across all parameters and assets, illustrating the overall consistency of TL’s advantage. The matrix demonstrates that TL achieved the highest pairwise win rate in terms of RMSE, outperforming both AS and GM models across the majority of degradation parameters and equipment types. This reinforces the quantitative evidence of TL’s dominant predictive reliability.

4.4.3. Cross-Parameter and Cross-Asset Generalization

At the parameter level, elements such as Magnesium, Calcium, and Iron (

Table 5) displayed high average R

2 values across TL models, demonstrating strong inter-equipment consistency for chemically stable wear and additive markers. Less stable indicators (e.g., Sodium, Lead, and Silicon) retained lower transferability due to sporadic contamination events and inconsistent sampling. However, even for these difficult cases, TL maintained positive predictive capacity where GM and AS models failed entirely.

Across equipment classes, TL’s adaptability was most pronounced in Shovels and Wheel Loaders, where operational variability and sensor noise were high. In contrast, for Dump Trucks—characterized by more homogeneous duty cycles—GM models occasionally approached TL performance, highlighting that transfer benefits scale with environmental and operational diversity.

Synthesizing across metrics, TL emerges as a scalable and physically interpretable modeling paradigm. It effectively bridges the gap between local specialization and global generalization, preserving the nonlinear degradation signatures specific to each asset while leveraging the shared physical–chemical progression patterns learned from the broader fleet. This balanced performance translates into lower structural bias, reduced error sensitivity, and improved uncertainty calibration across diverse operational contexts.