Wear and Friction Reduction on Polyethersulfone Matrix Composites Containing Polytetrafluoroethylene Coated with ZrW2O8 Particles at Elevated Temperatures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Wear of Neat PES

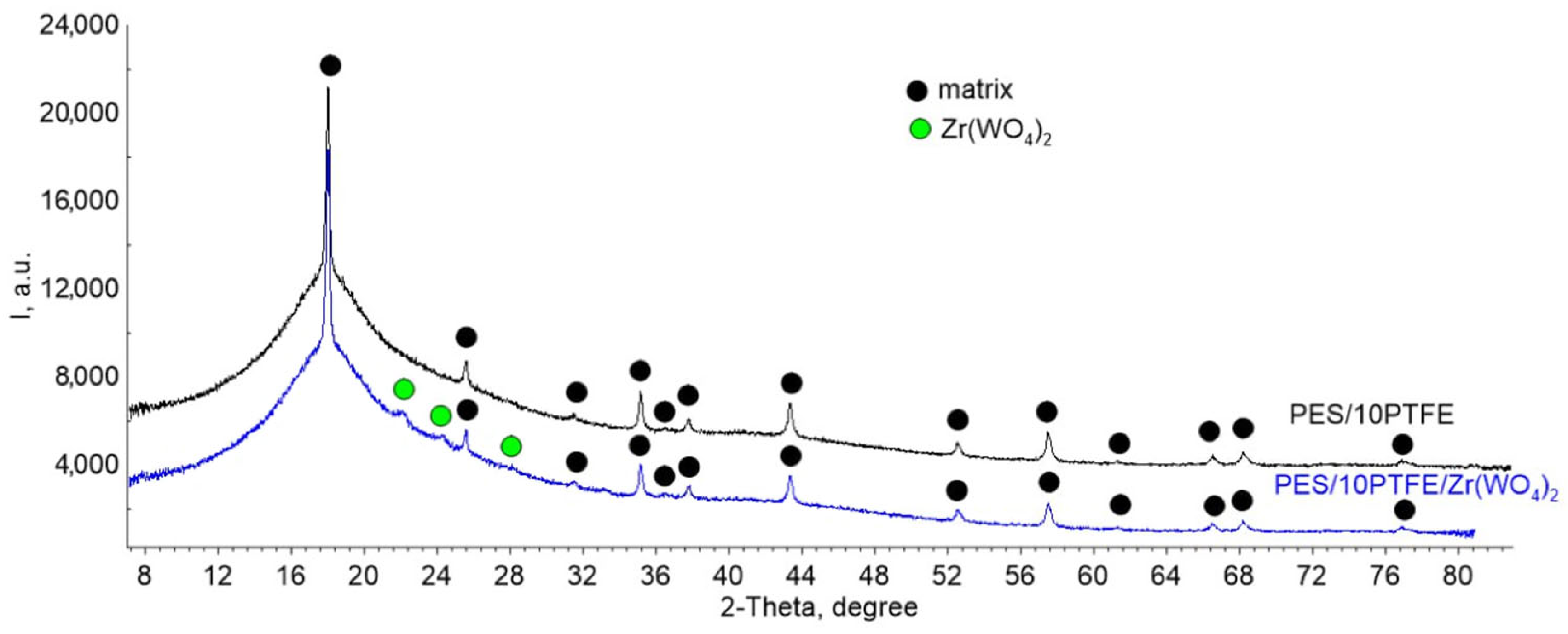

3.2. Phases and Structures in As-Prepared PMCs

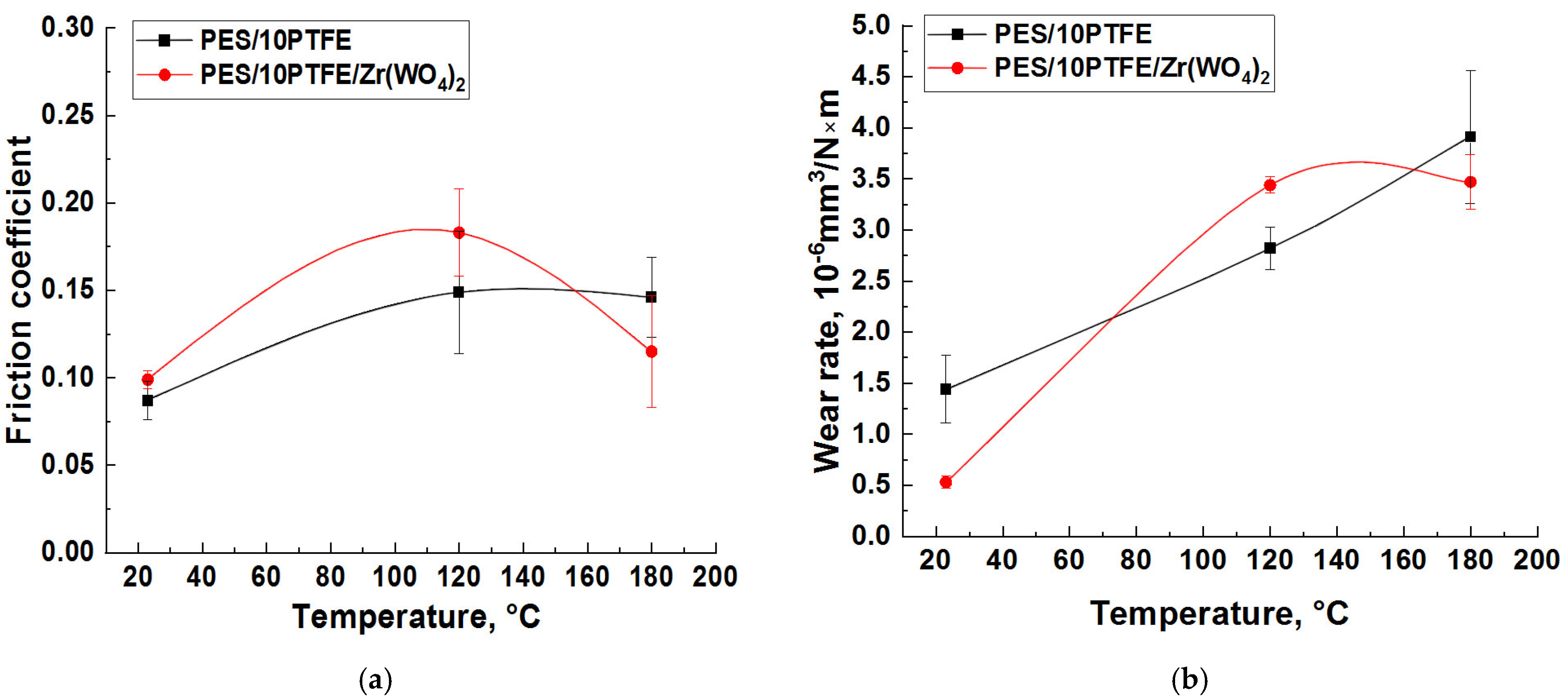

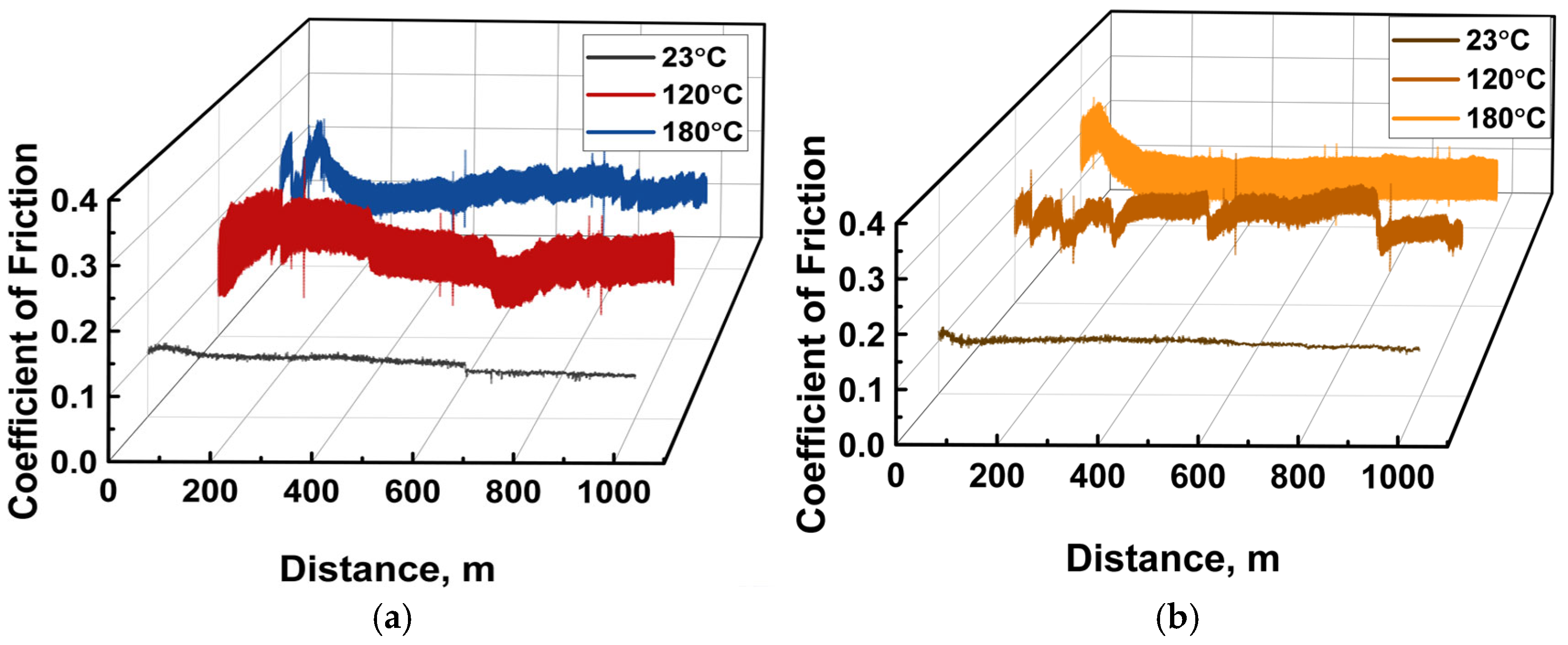

3.3. Wear and Friction Characteristics

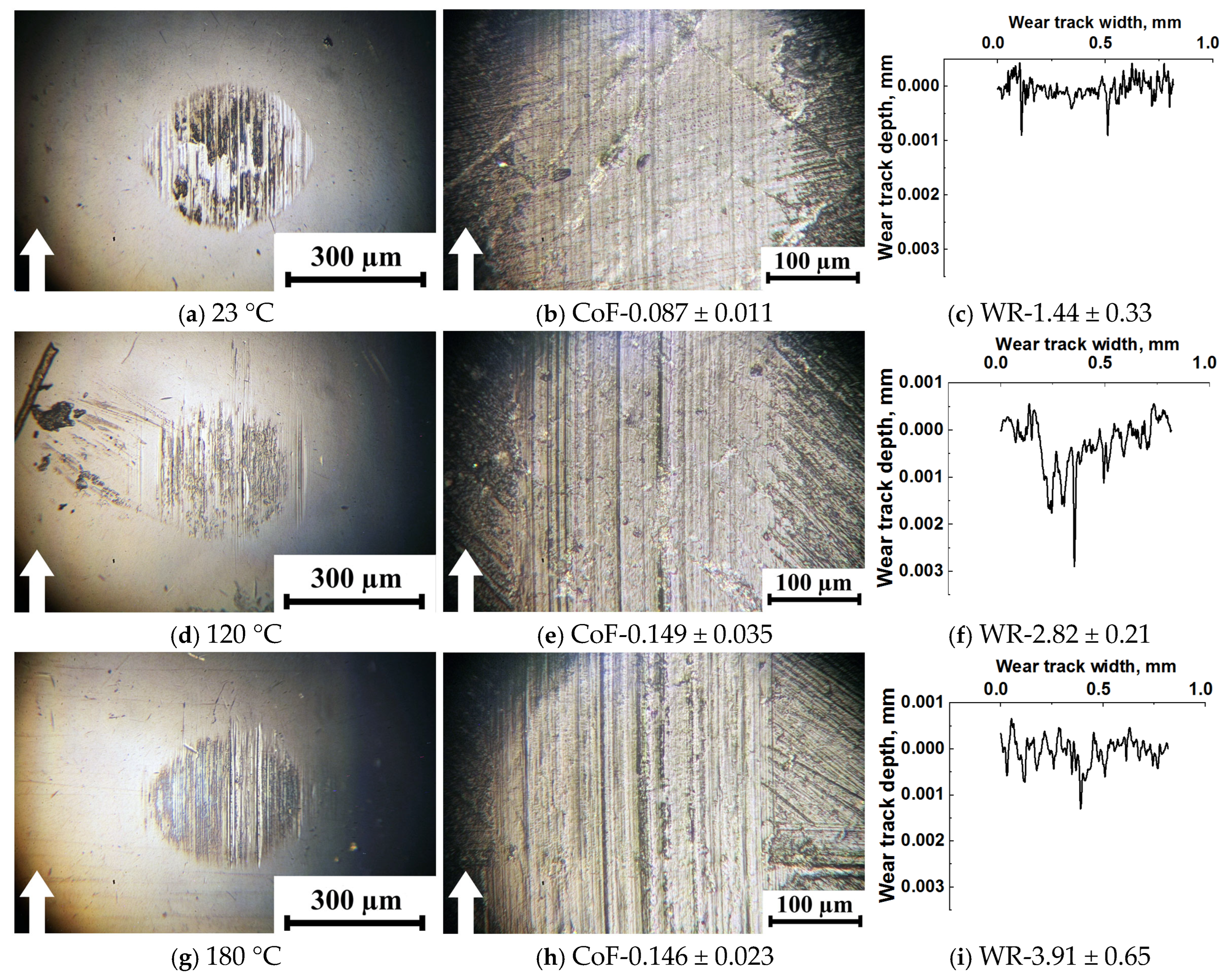

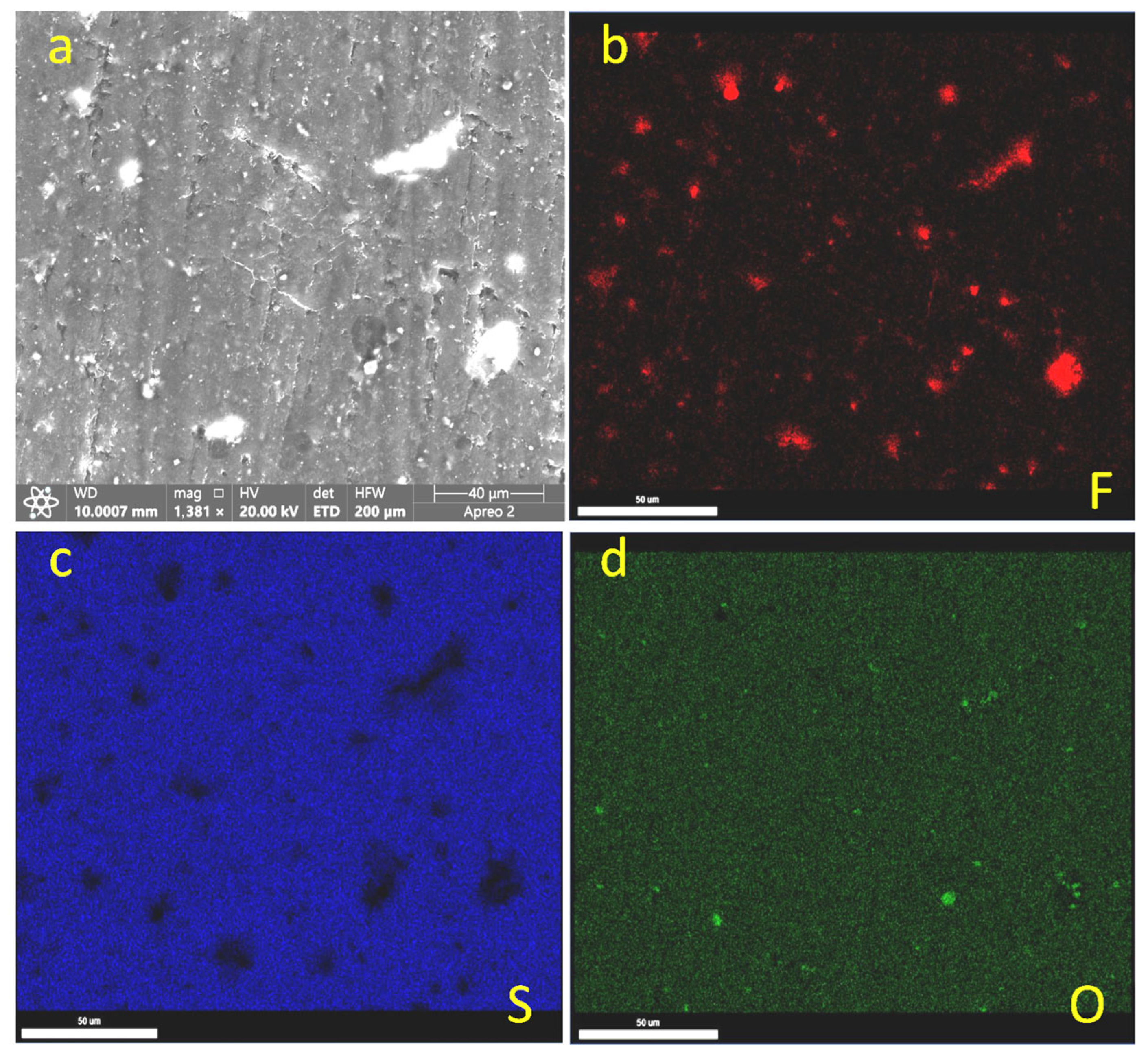

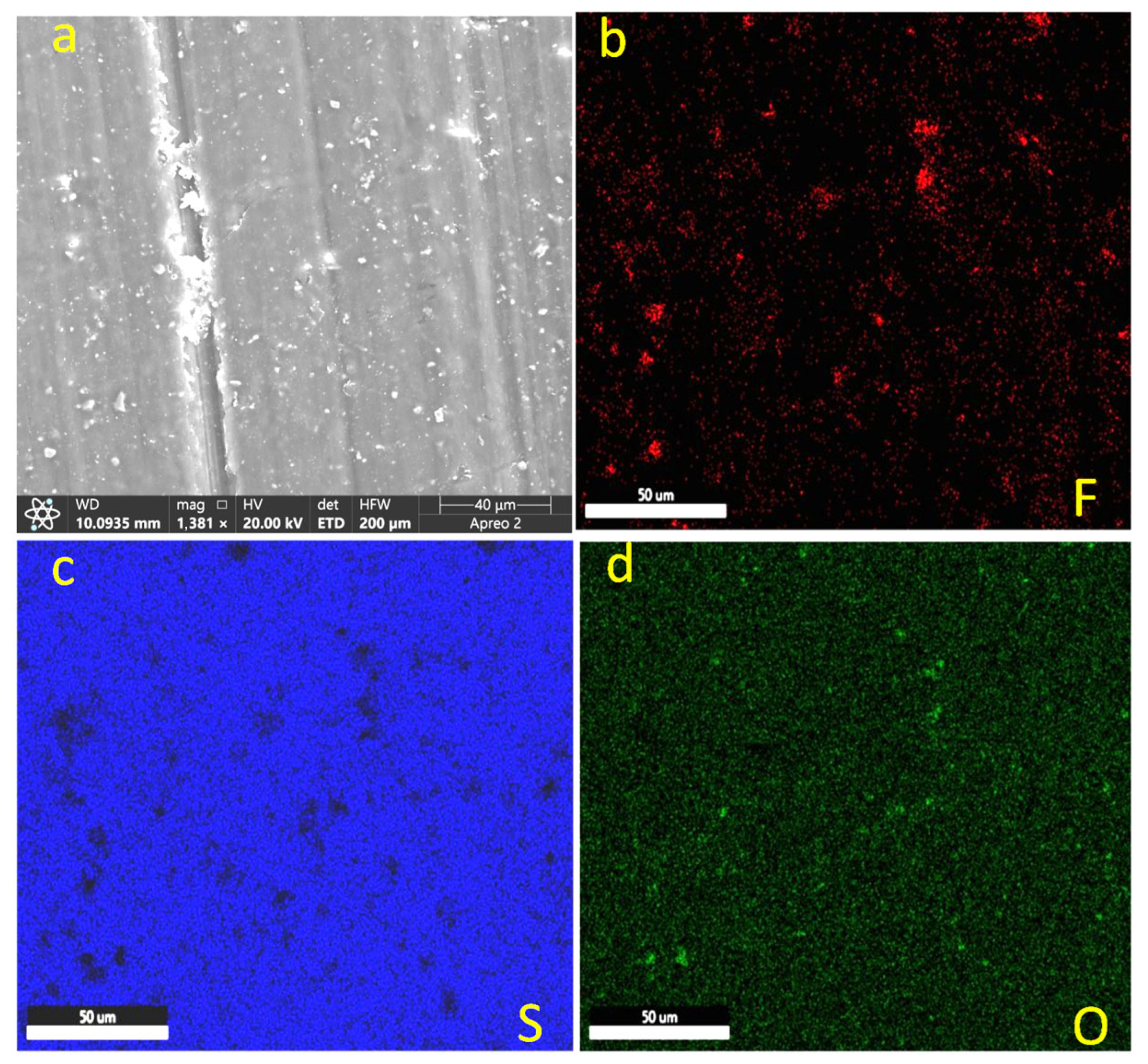

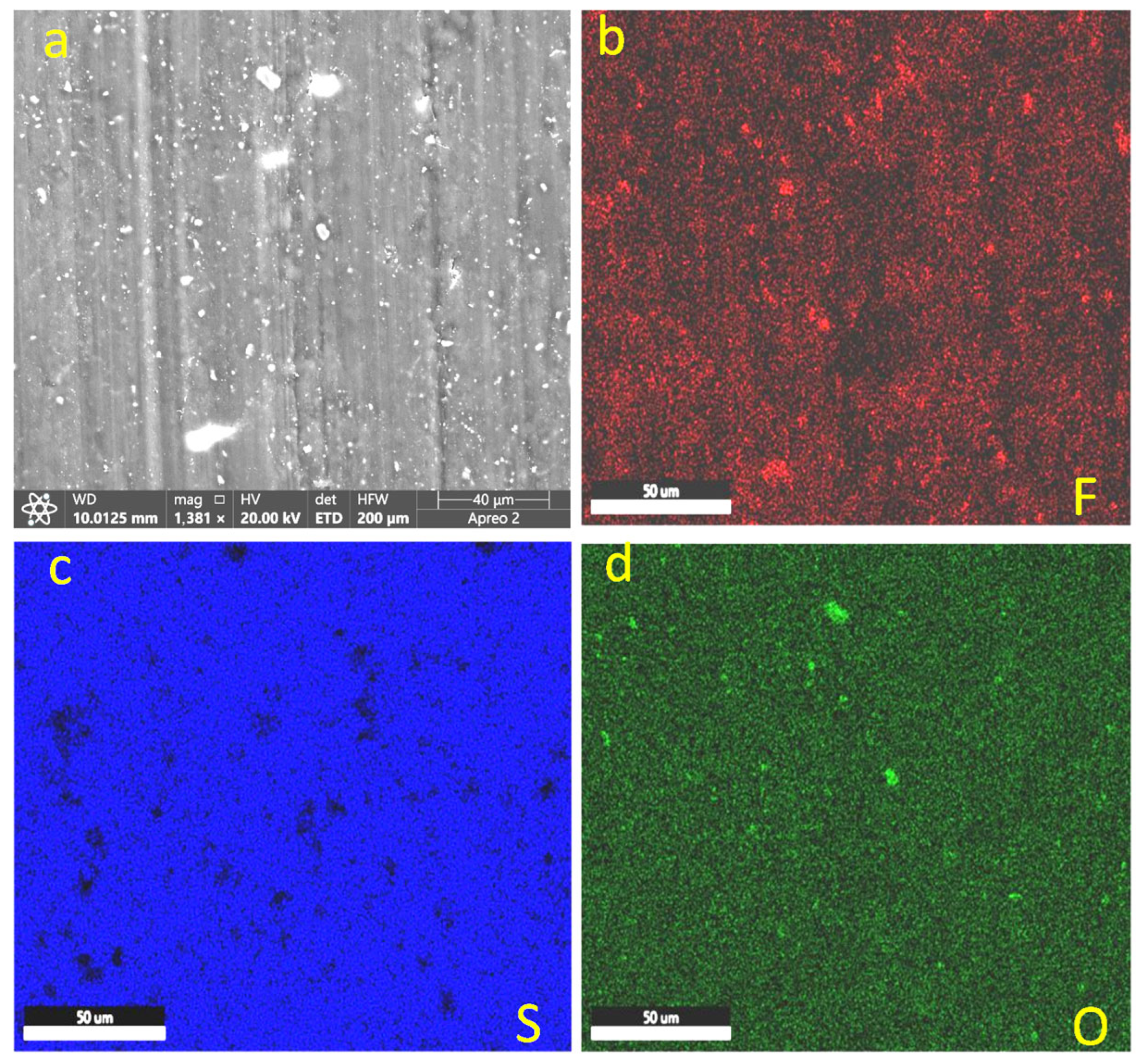

3.4. Steel Counterpart’s Worn Surface Examination

3.5. PMC’s Worn Surface Examination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PMC | Polymer matrix composite |

| PES | Polyethersulfone |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| ZT | Zirconium tungstate |

| CTE | Coefficient of thermal expansion |

| NTE | Negative thermal expansion |

| CoF | Coefficient of friction |

| WR | Wear rate |

References

- Grigoriev, A.; Shilko, E.; Dmitriev, A.; Tarasov, S. Suppression of wear in dry sliding friction induced by negative thermal expansion. Phys. Rev. E 2020, 102, 042801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoriev, A.S.; Shilko, E.V.; Dmitriev, A.I.; Tarasov, S.Y. Modeling Wear and Friction Regimes on Ceramic Materials with Positive and Negative Thermal Expansion. Lubricants 2023, 11, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushotham, N.; Parthasarathi, N.L.; Suresh, B.P.; Sivakumar, G.; Rajasekaran, B. Effect of thermal expansion on the high temperature wear resistance of Ni-20%Cr detonation spray coating on IN718 substrate. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 462, 129490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Wang, W.; Chen, J.; Zhao, S.; Gu, W.; Nan, J.; Ji, Y.; Xia, Y.; Mao, Z.; Zhu, L.; et al. Negative expansion induced anti-abrasive self-cleaning coatings for enhancing output of solar panels. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternak, E.; Dyskin, A. Negative Thermal Expansion Realized by an Incomplete Bimaterial Ring. Phys. Status Solidi B 2024, 261, 2400048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Xiang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Feng, S.; Yu, Z.; Mo, J. Effect of friction block thickness on the high-temperature tribological behavior of the braking interface of high-speed train. Tribol. Int. 2025, 201, 110232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lu, C.; Liu, X.; Sun, T.; Mo, J. The influence of competition between thermal expansion and braking parameter on the wear degradation of friction block. Tribol. Int. 2024, 192, 109246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Kalifa, M.; Khan, M.; Yang, Y. Interplay Between Wear and Thermal Expansion in 6082 Aluminum: A Simulation and Experimental Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, F.; Wang, B.; Zhao, S.; Liu, M.; Zheng, J.; Li, Z.; Hu, C.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, Q. Synergistic Enhancement Effect of Polytetrafluoroethylene and WSe2 on the Tribological Performance of Polyetherimide Composites. Lubricants 2025, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Cong, P.; Liu, X.; Li, T. Comparative Study of Tribological Properties of Polyphenylene Sulfide (PPS), Polyethersulfone (PES), and Polysulfone (PSU). J. Macromol. Sci. Part B Phys. 2009, 48, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, G.; Chukov, D.; Tcherdyntsev, V.; Torokhov, V. Effect of Formation Route on the Mechanical Properties of the Polyethersulfone Composites Reinforced with Glass Fibers. Polymers 2019, 11, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen Du, S.; Li, F.; Xiao, H.M.; Li, Y.Q.; Hu, N.; Fu, S.Y. Tensile and flexural properties of graphene oxide coated-short glass fiber reinforced polyethersulfone composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 99, 407–415. [Google Scholar]

- Oprea, M.; Pandele, A.M.; Enachescu, C.I.; Antoniac, I.V.; Voicu, S.I.; Fratila, A.M. Crown Ether-Functionalized Polyethersulfone Mem-branes with Potential Applications in Hemodialysis. Polymers 2025, 17, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasyłeczko, M.; Wojciechowski, C.; Chwojnowski, A. Polyethersulfone Polymer for Biomedical Ap-plications and Biotechnology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chung, T.-S. Fabrication and applications of polyethersulfone hollow fiber membranes. Hollow Fiber Membr. 2021, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Yang, Y.; Song, L.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, X. Characterization and Tribological Performance of Polyethersulfone/PTFE Compound Filled with Na-Montmorillonite. Tribol. Lett. 2021, 69, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torokhov, V.G.; Chukov, D.I.; Tcherdyntsev, V.V.; Sherif, G.; Zadorozhnyy, M.Y.; Stepashkin, A.A.; Larin, I.I.; Medvedeva, E.V. Mechanical and Thermophysical Properties of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polyethersulfone. Polymers 2022, 14, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Bijwe, J.; Singh, K. Studies for Wear Property Correlation for Carbon Fabric-Reinforced PES Composites. Tribol. Lett. 2011, 43, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Hua, Y.; Qu, C.B.; Xiao, H.M.; Fu, S.Y. Greatly enhanced cryogenic mechanical properties of short carbon fiber/polyethersulfone composites by graphene oxide coating. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 89, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veveris, A.A.; Kaloshkin, S.D. Production and Properties of Towpregs Based on Carbon Fibers Impregnated with Polyethersulfone by the Solution Method. Inorg. Mater. Appl. Res. 2025, 16, 1052–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ding, L.; Zhao, Y.; Han, Y.; Jiang, Z. Friction and wear properties of poly(ether sulfone) containing perfluorocarbon end group. High Perform. Polym. 2018, 30, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Bijwe, J. Influence of fiber–matrix adhesion and operating parameters on sliding wear performance of carbon fabric polyethersulphone composites. Wear 2011, 271, 2919–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.H.; Yan, S.C.; Chen, Y. Thermomechanical and tribological properties of polyimide and polyethersulfone blends reinforced with expanded graphite particles at various elevated tempera-tures. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 52512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamah, S.C.; Goh, P.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Suzaimi, N.D.; Yogarathinam, L.T.; Raji, Y.O.; El-badawy, T.H. Recent development in modification of polysulfone membrane for water treatment application. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 40, 101835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panin, S.V.; Luo, J.; Buslovich, D.G.; Alexeenko, V.O.; Berto, F.; Kornienko, L.A. Effect of Transfer Film on Tribological Properties of Anti-Friction PEI- and PI-Based Composites at Elevated Temperatures. Polymers 2022, 14, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.W.S.; Liu, W.; Xue, Q. An Investigation of the Friction and Wear Behaviors of Polyphenylene Sulfide Filled with Solid Lubricants. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2000, 40, 1825–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Song, L.; Yang, Y. Tribological behavior of polyethersulfone-reinforced polytetra-fluoroethylene composite under dry sliding condition. Tribol. Int. 2015, 86, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, S.Y.; Buslovich, D.G.; Panin, S.V.; Savchenko, N.L.; Kornienko, L.A.; Filatov, E.Y.; Moskvichev, E.N. Structure and tribological behavior of a polyetherimide/polytetrafluoroethylene matrix filled with negative thermal expansion zirconium tungstate particles. Wear 2024, 558–559, 205567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.M.; Wright, B.A.; Wright, W.W. Thermal degradation of fluorine-containing polymers-1,2. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1964, 8, 2935–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.N.; Rae, P.J.; Dattelbaum, D.M.; Clausen, B.; Brown, D.W. In-situ Measurement of Crystalline Lattice Strains in Polytetrafluoroethylene. Exp. Mech. 2008, 48, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, Y.; Nishijima, S. Characterization of the melting process of PTFE using positron annihilation spectroscopy. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2015, 618, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Pei, J.; Zhuo, W.; Niu, Y.; Lia, G. The deformation mechanism and phase transition behavior of polytetrafluoroethylene Phase transition behavior and deformation mechanism of polytetrafluoroethylene under stretching. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 39813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.T.; Pei, Y.T.; De Hosson, J.T.M. Structural changes in polytetrafluoroethylene molecular chains upon sliding against steel. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 1484–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubanov, A.I.; Dedova, E.S.; Pavel, E.P.; Filatov, E.Y.; Kardash, T.Y.; Korenev, S.V.; Kulkov, S.N. Some peculiarities of zirconium tungstate synthesis by thermal decomposition of hydrothermal precursors. Thermochim. Acta 2014, 597, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnov, A.P.; Shaposhnikova, V.V.; Salazkin, S.N.; Askadskii, A.A.; Goroshkov, M.V.; Naumkin, A.V. Effect of Chemical Structures of Heat-Resistant Tribostable Thermoplastics on Their Tribological Properties: Establishing a General Relationship. INEOS OPEN 2019, 2, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.S.O.; Mary, T.A.; Vogt, T.; Subramanian, M.A.; Sleight, A.W. Negative Thermal Expansion in ZrW2O8 and HfW2O8. Chem. Mater. 1996, 8, 2809–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenta, F.; Bolelli, G.; D’Errico, F.; Ottani, F.; Pedrazzi, S.; Allesina, G.; Bertarini, A.; Puddu, P.; Lusvarghi, L. Tribological behavior of PTFE composites: Interplay between reinforcement type and counterface material. Wear 2022, 510–511, 204498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Zhao, S.; Lin, L.; Schlarb, A.K. Tribological performance of a polyethersulfone (PESU)-based nanocomposite with potential surface changes of the metallic counterbody. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 636, 157850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements, wt. %/at. % | O | Zr | W |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectrum 1 Spectrum 2 Spectrum 3 Spectrum 4 Mean percentage | 32.33/81.94 24.92/75.97 21.24/72.48 9.59/49.23 22.24/69.90 | 17.16/7.42 15.25/8.15 13.69/8.20 22.84/20.58 17.24/11.09 | 49.61/10.64 59.83/15.87 65.07/19.33 67.57/30.20 60.52/19.01 |

| Standard deviation | 9.82/14.33 | 4.0/6.34 | 7.96/8.27 |

| Max | 33.23/81.94 | 22.84/20.58 | 67.57/30.20 |

| Min | 9.59/49.23 | 13.69/7.42 | 49.61/10.64 |

| № | Composite | Temperature, T, °C | Coefficient of Friction, ƒ | Wear Rate I, (10−6 mm3/Nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PES/PTFE | 23 | 0.087 ± 0.011 | 1.44 ± 0.33 |

| 2 | 120 | 0.149 ± 0.035 | 2.82 ± 0.21 | |

| 3 | 180 | 0.146 ± 0.023 | 3.91 ± 0.65 | |

| 4 | PES/PTFE/ZT | 23 | 0.099 ± 0.005 | 0.53 ± 0.06 |

| 5 | 120 | 0.183 ± 0.025 | 3.44 ± 0.08 | |

| 6 | 180 | 0.115 ± 0.032 | 3.47 ± 0.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dmitriev, A.I.; Tarasov, S.Y.; Buslovich, D.G.; Panin, S.V.; Savchenko, N.L.; Kornienko, L.A.; Filatov, E.Y.; Moskvichev, E.N.; Lychagin, D.V. Wear and Friction Reduction on Polyethersulfone Matrix Composites Containing Polytetrafluoroethylene Coated with ZrW2O8 Particles at Elevated Temperatures. Lubricants 2025, 13, 535. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120535

Dmitriev AI, Tarasov SY, Buslovich DG, Panin SV, Savchenko NL, Kornienko LA, Filatov EY, Moskvichev EN, Lychagin DV. Wear and Friction Reduction on Polyethersulfone Matrix Composites Containing Polytetrafluoroethylene Coated with ZrW2O8 Particles at Elevated Temperatures. Lubricants. 2025; 13(12):535. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120535

Chicago/Turabian StyleDmitriev, Andrey I., Sergei Yu. Tarasov, Dmitry G. Buslovich, Sergey V. Panin, Nikolai L. Savchenko, Lyudmila A. Kornienko, Evgeny Yu. Filatov, Evgeny N. Moskvichev, and Dmitry V. Lychagin. 2025. "Wear and Friction Reduction on Polyethersulfone Matrix Composites Containing Polytetrafluoroethylene Coated with ZrW2O8 Particles at Elevated Temperatures" Lubricants 13, no. 12: 535. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120535

APA StyleDmitriev, A. I., Tarasov, S. Y., Buslovich, D. G., Panin, S. V., Savchenko, N. L., Kornienko, L. A., Filatov, E. Y., Moskvichev, E. N., & Lychagin, D. V. (2025). Wear and Friction Reduction on Polyethersulfone Matrix Composites Containing Polytetrafluoroethylene Coated with ZrW2O8 Particles at Elevated Temperatures. Lubricants, 13(12), 535. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120535