Influence of Nano-Lubricants on Edge Cracking and Surface Quality of Rolled Mg/Al Composite Foils

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Titanium Dioxide Nano-Lubricant

2.3. Friction and Wear Tests

2.4. Micro Rolling Test

2.5. Theoretical Basis for Rolling Force Reduction by Nano-Lubricant

2.6. Characterization and Analytical Approaches

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Variations in COF Under Different Lubrication Conditions

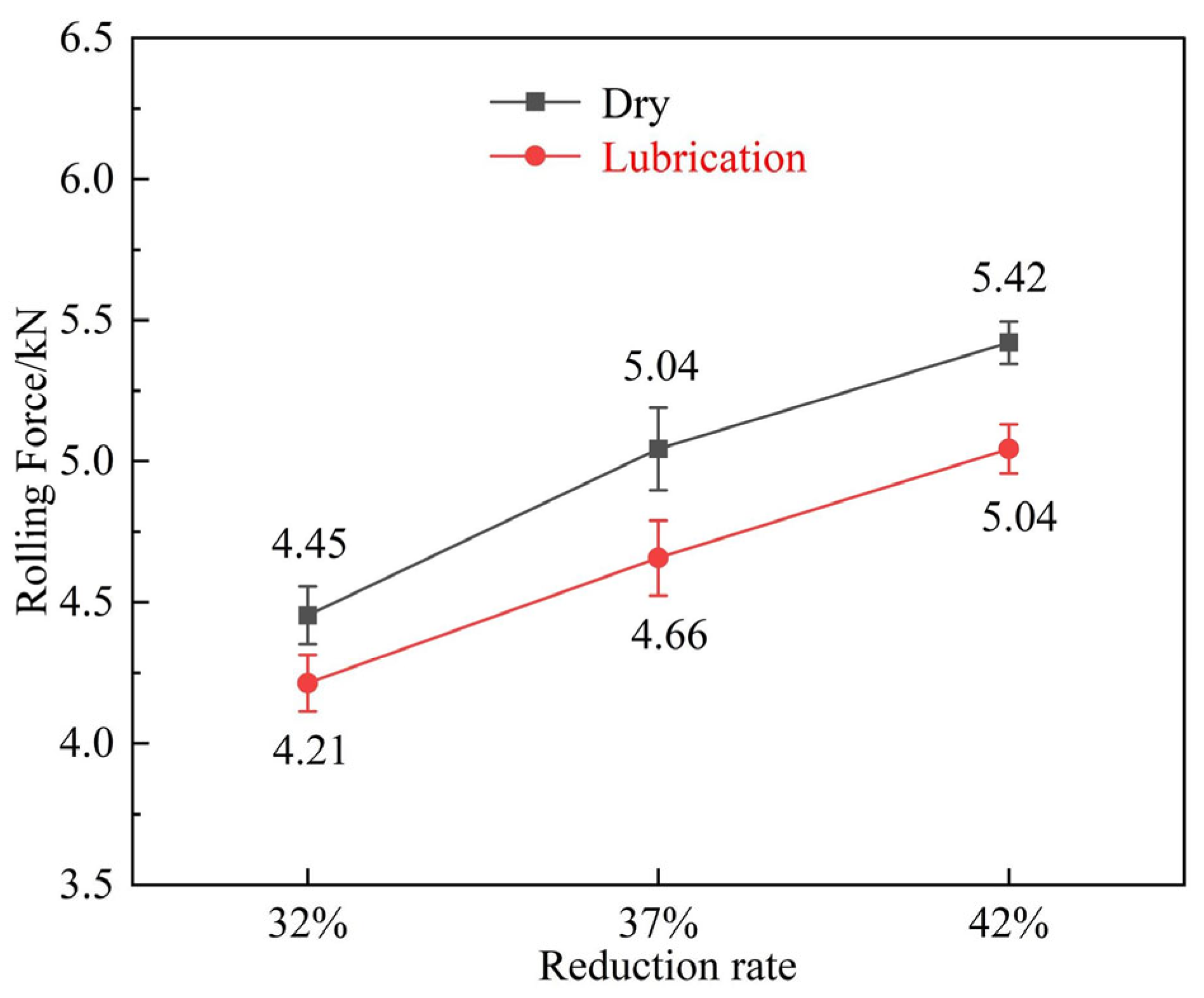

3.2. Variation in Rolling Force Under Different Rolling Conditions

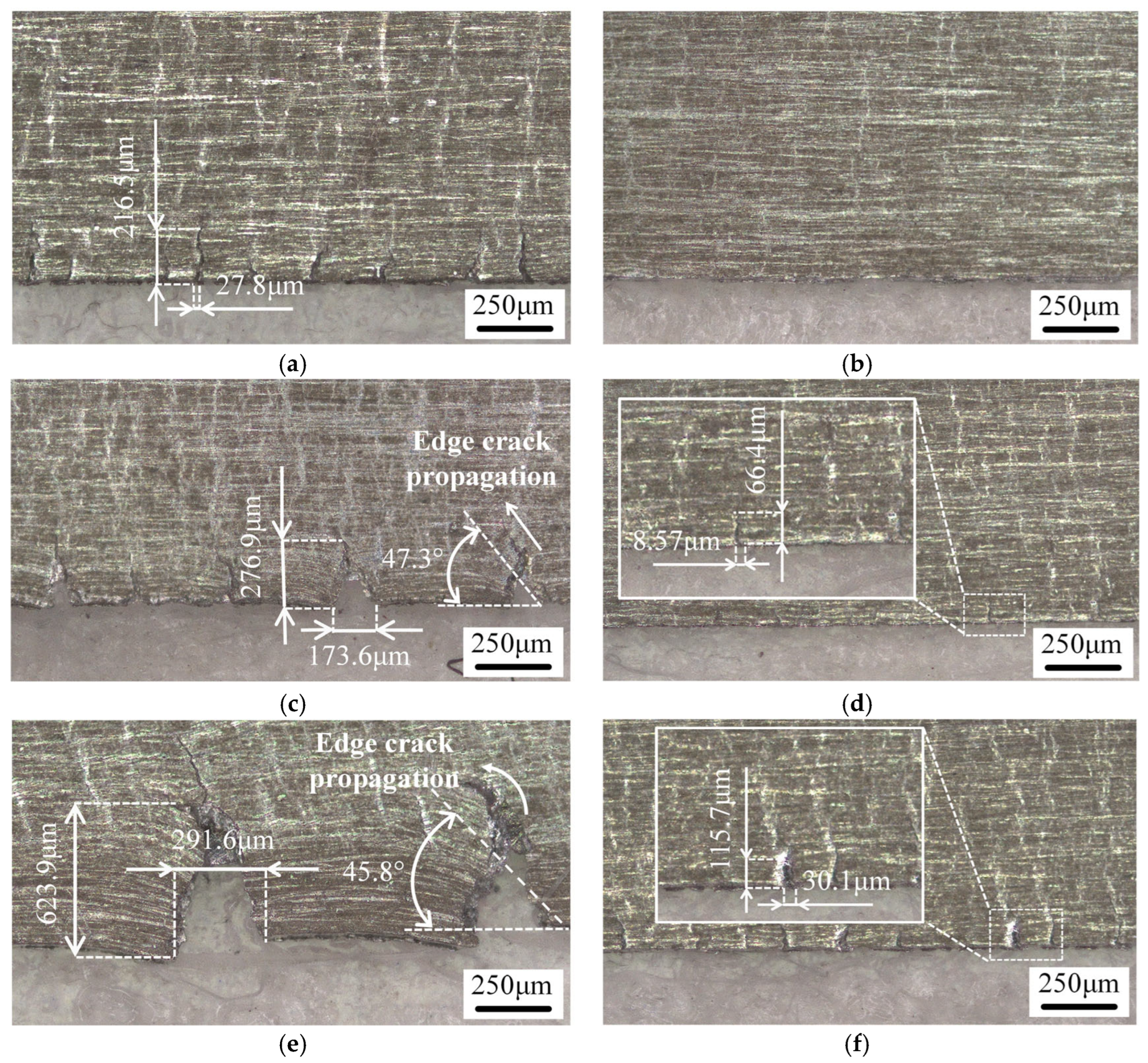

3.3. Influence of Various Rolling Conditions on Foil Edge Quality

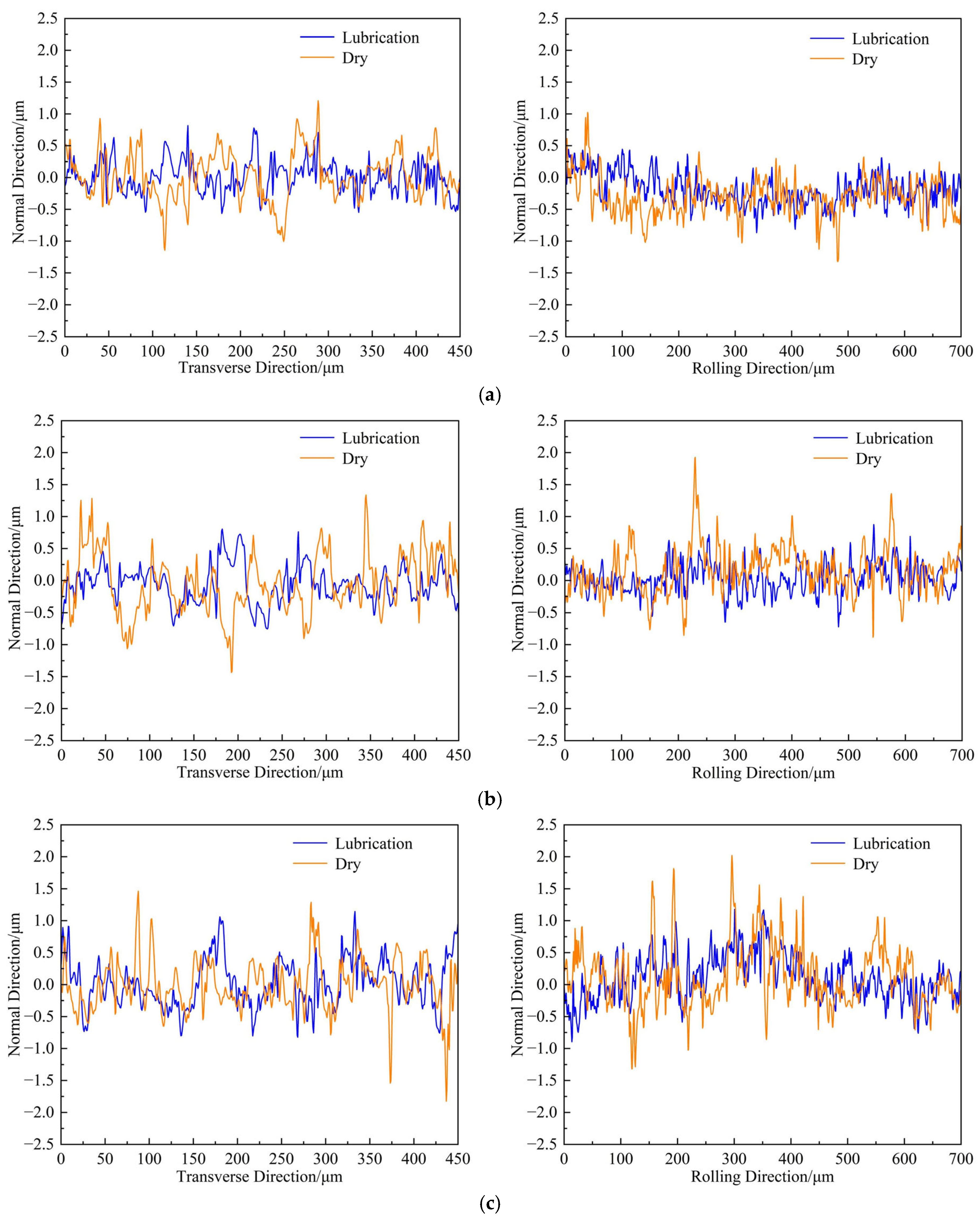

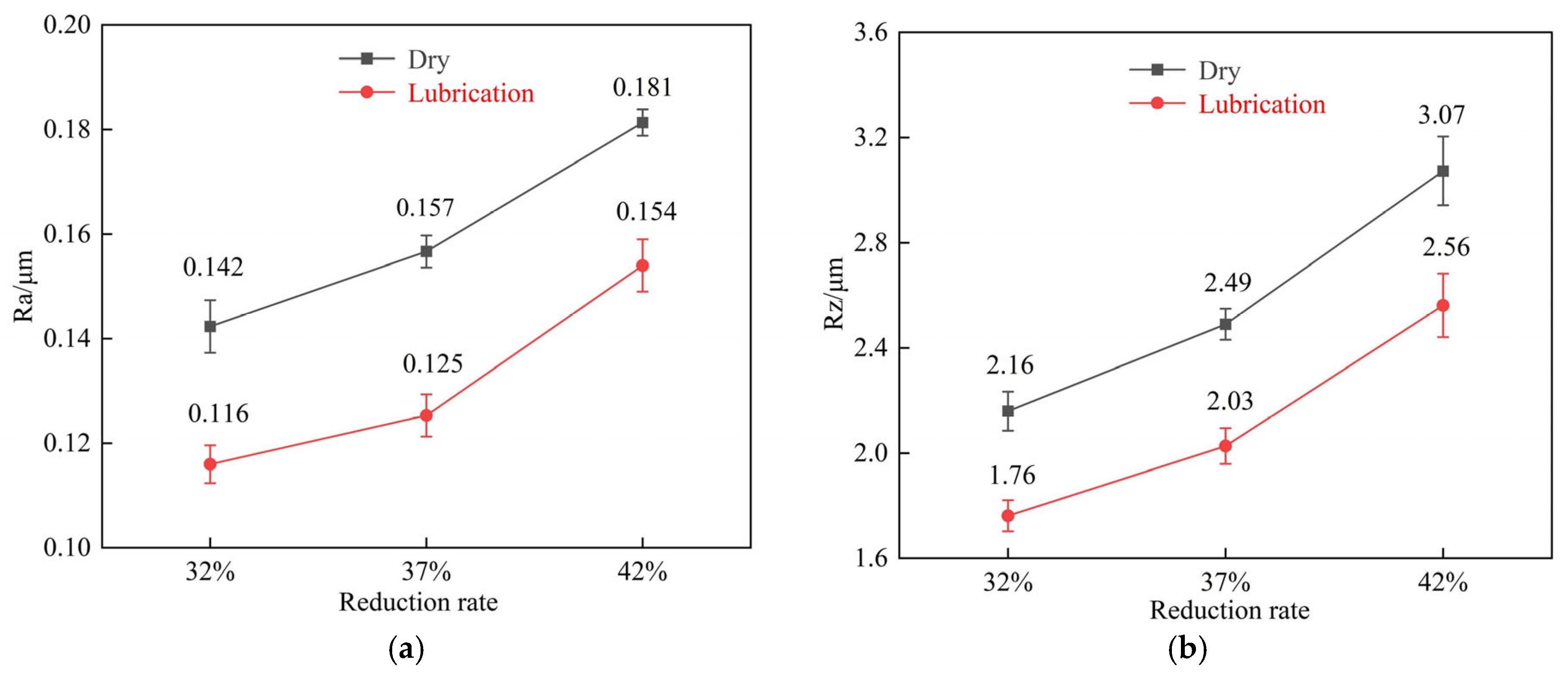

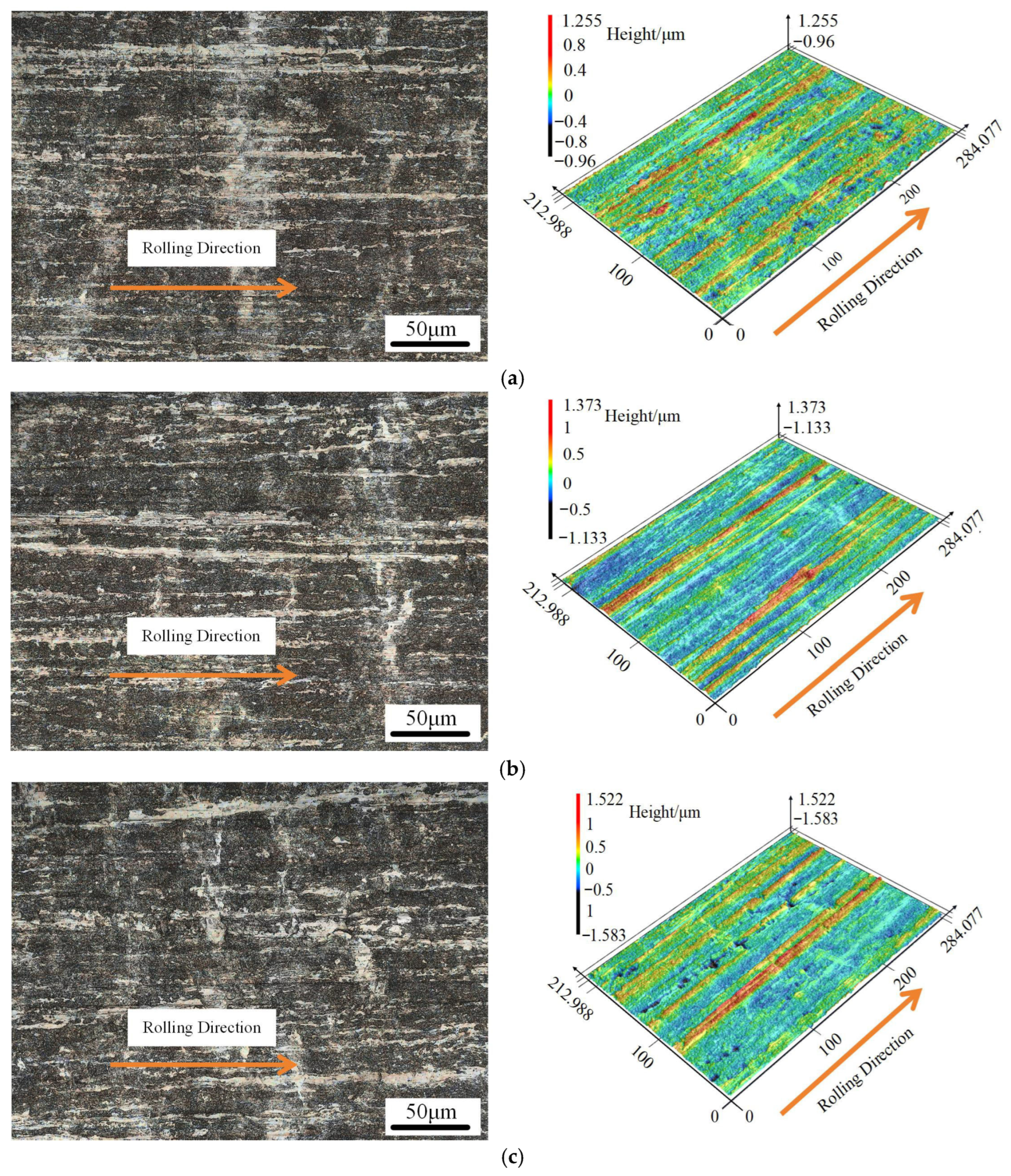

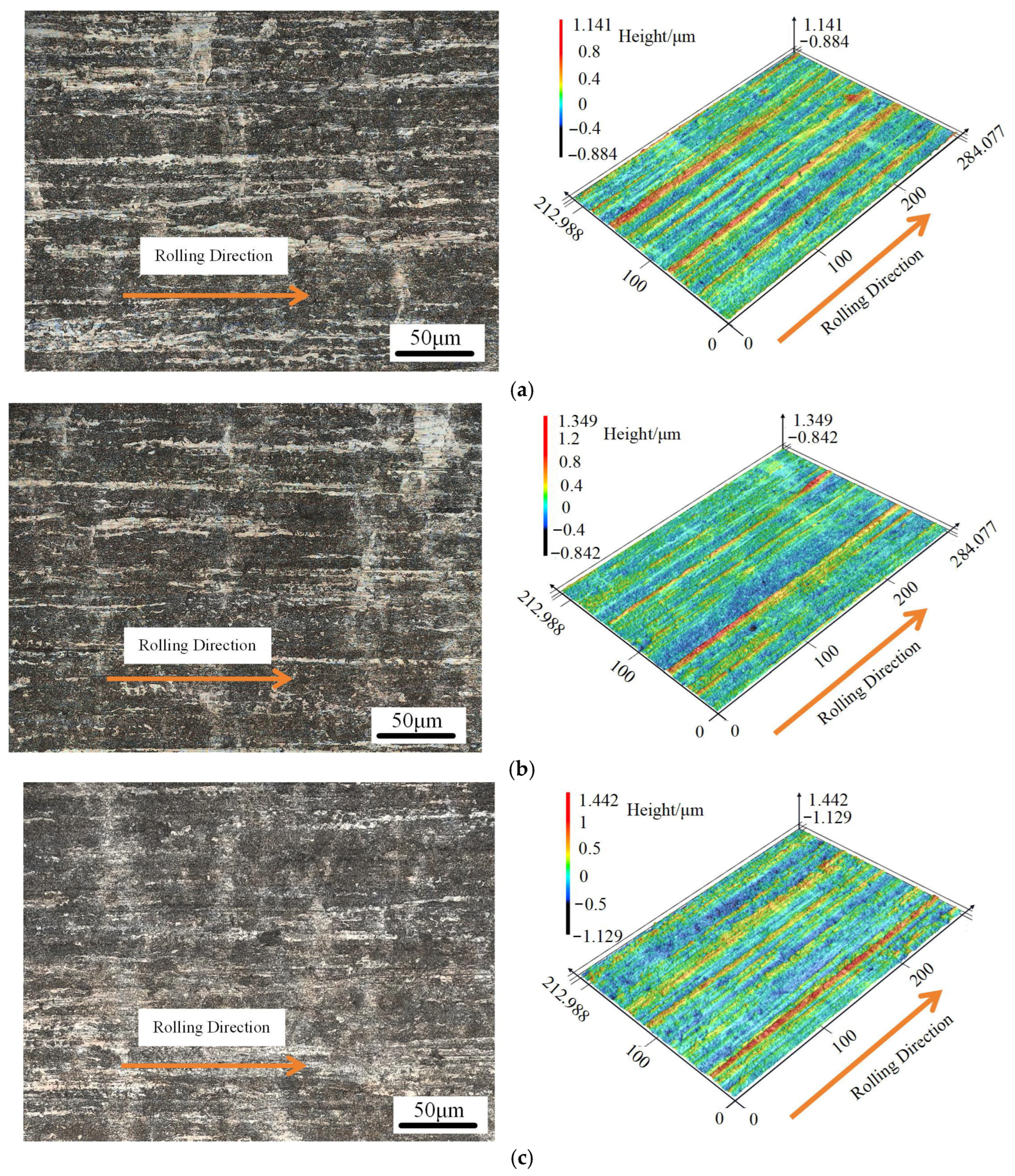

3.4. Variation in Foil Surface Quality Under Different Rolling Conditions

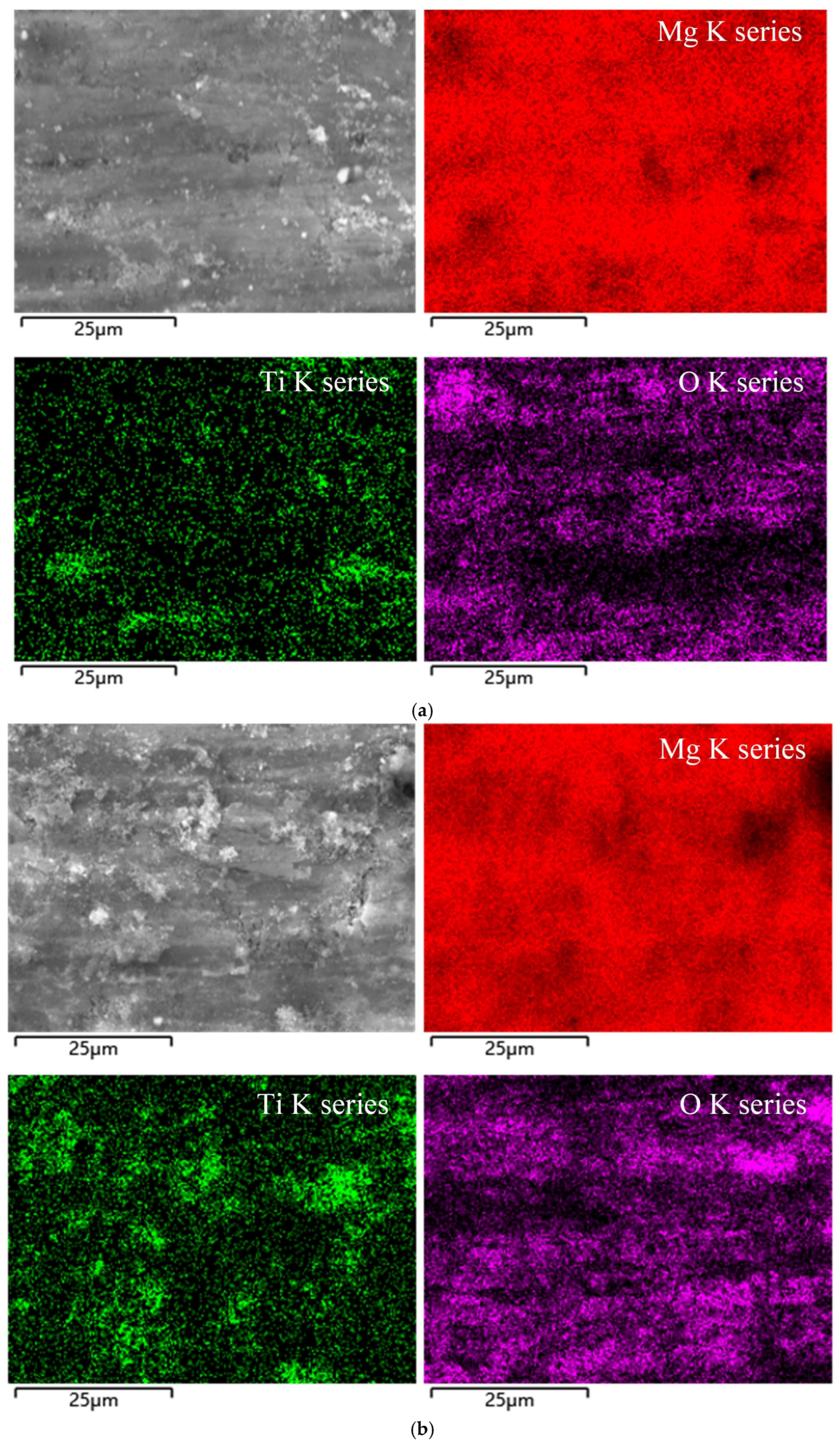

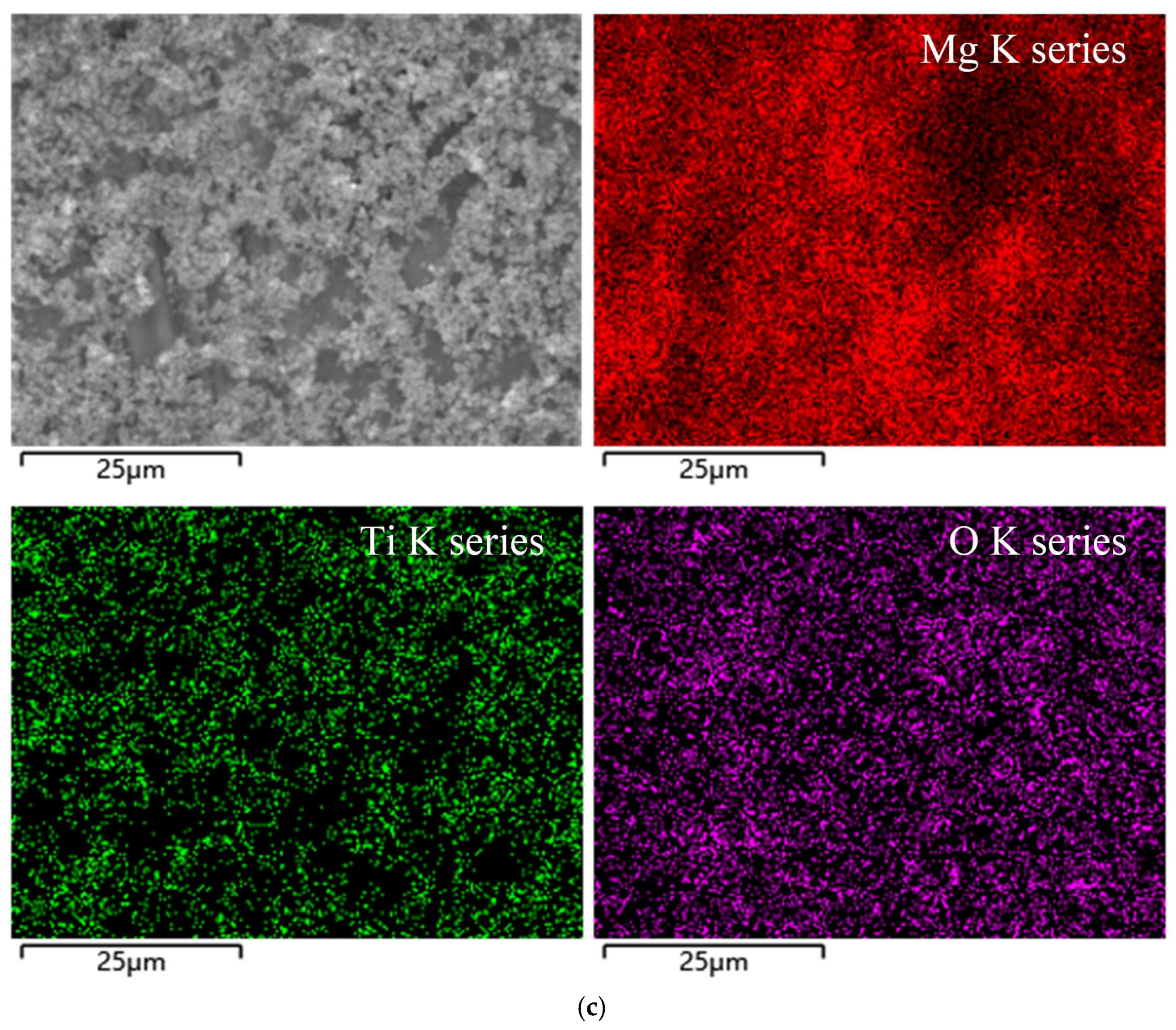

3.5. SEM-EDS Analysis

3.6. Lubrication Mechanism

4. Conclusions

- The TiO2 nano-lubricant significantly reduced the COF during the sliding contact of magnesium foils. An optimal concentration of 3.0 wt.% was identified, at which the system achieved a minimum average COF of 0.067. Both lower and higher concentrations resulted in less effective lubrication, with the deterioration at high concentrations attributed to nanoparticle agglomeration.

- The application of the 3.0 wt.% nano-lubricant during the rolling of Mg/Al composite foils effectively reduced the rolling force by 5.39% to 7.54%, which is consistent with the predictions of the Bland-Ford-Hill model. This reduction in rolling force led to a decrease in interfacial shear stress, a key driver for edge crack initiation.

- The nano-lubricant profoundly suppressed the initiation and propagation of edge cracks on the magnesium side. Under dry conditions, edge cracks underwent severe transverse propagation and coalescence, leading to deteriorated edge quality at higher reduction rates. In contrast, the nano-lubricant confined cracks to the immediate edge region, limited their transverse propagation, and prevented their coalescence. Furthermore, by promoting more coordinated metal flow and improving deformation uniformity, the nano-lubricant reduced the height profile fluctuation range by 33% to 45% in both the transverse and rolling directions, contributing to superior dimensional stability.

- The surface quality of the rolled foils was significantly improved by the nano-lubricant, which reduced the surface roughness parameters Ra and Rz by 16.5% to 24.0% compared to dry conditions. This improvement is attributed to a more uniform deformation and the elimination of microcracks, as directly evidenced by the smoother surface morphology and reduced height profile fluctuations.

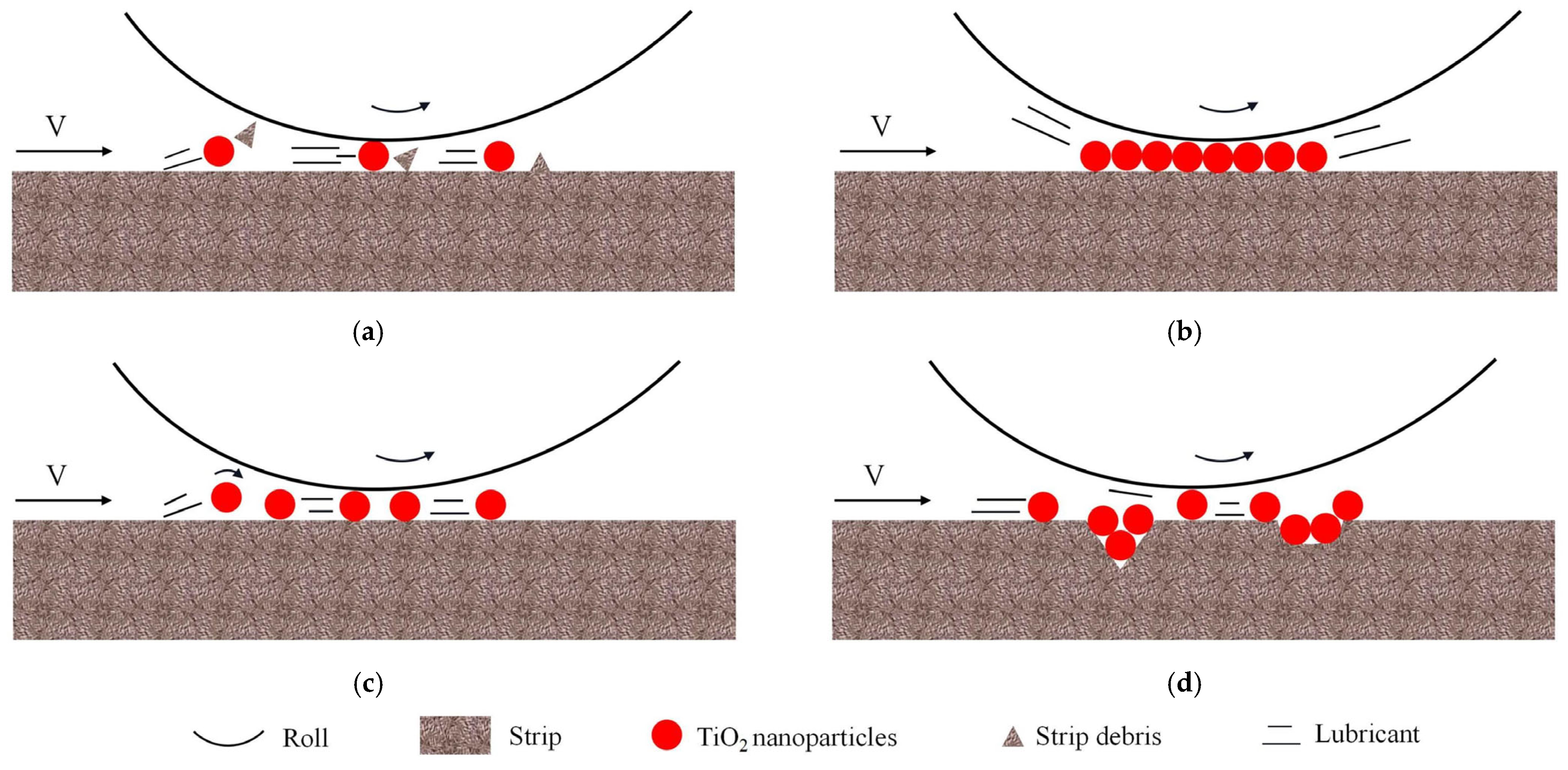

- The superior performance is attributed to the synergistic operation of four lubrication mechanisms: the rolling effect and mending effect, which were primarily responsible for reducing the COF and rolling force and for suppressing crack propagation, respectively; and the polishing effect and protective film effect, which collectively enhanced the surface finish. SEM-EDS analysis provided direct evidence of the TiO2 nanoparticle distribution, confirming the formation of a lubricating film and the filling of surface defects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chircov, C.; Grumezescu, A.M. Microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) for biomedical applications. Micromachines 2022, 13, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Shi, J.; Ju, D. Effect of Prior Rolling on Microstructures and Property of Diffusion-Bonded Mg/Al Alloy. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 4535984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Li, G.; Xu, G.; Fang, M.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, W.; Zhang, M. Evolution and Formation Mechanism of Interface Structure in Rolled Mg-Al Clad Sheet. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 32, 7248–7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Bian, L.; Huang, Q. Microstructural evolution and mechanical behavior of Mg/Al laminated composite sheet by novel corrugated rolling and flat rolling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 765, 138318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, D.; Cao, X.; Yang, W.; Wang, W. Influence of multi-pass rolling and subsequent annealing on the interface microstructure and mechanical properties of the explosive welding Mg/Al composite plates. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 723, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Luo, Q.; Song, J.; Xiao, B.; Jiang, B.; Wu, L.; Zhao, H.; Shen, Q.; Pan, F. Ameliorating the edge cracking behavior of Mg-Mn-Al alloy sheets prepared by multi-pass online heating rolling. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 85, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.; Sutcliffe, M. Analysis of surface roughness of cold-rolled aluminium foil. Wear 2000, 244, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Lu, H.; Zhang, W.; Nie, H.; Shi, Q.; Deng, J.; Liang, W.; Wang, L. An effective rolling process of magnesium alloys for suppressing edge cracks: Width-limited rolling. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, 10, 2193–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Huang, H.; Yan, M. Inhibition behavior of edge cracking in the AZ31B magnesium alloy cold rolling process with pulsed electric current. Metals 2023, 13, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Wei, J.; Ma, L.; Wu, D.; He, D. Inhibitory effects of prefabricated crown on edge crack of rolled AZ31 magnesium alloy plate. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 246, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Jiang, Z.; Yuen, W. Analysis of friction and surface roughness effects on edge crack evolution of thin strip during cold rolling. Tribol. Int. 2011, 44, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballarini, R.; Plesha, M.E. The effects of crack surface friction and roughness on crack tip stress fields. Int. J. Fract. 1987, 34, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafošnik, B.; Glodež, S.; Ulbin, M.; Flašker, J. A fracture mechanics model for the analysis of micro-pitting in regard to lubricated rolling–sliding contact problems. Int. J. Fatigue 2007, 29, 1950–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiya, P. Geometrical characterization of surface roughness and its application to fatigue crack initiation. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1975, 21, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, P.L., Jr.; Costa, H.L. A Holistic Review of Surface Texturing in Sheet Metal Forming: From Sheet Rolling to Final Forming. Lubricants 2025, 13, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, X.; Xia, W.; He, A.; Yun, J.-H.; Huang, S.; Wang, L.; Huang, H.; Jiao, S. Friction and wear characteristics of TiO2 nano-additive water-based lubricant on ferritic stainless steel. Tribol. Int. 2018, 117, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, M.; Wu, H.; Xie, H.; Zhao, J.; Su, G.; Jia, F.; Li, Z.; Lin, F.; Li, S.; Zhang, H. Understanding the role of water-based nanolubricants in micro flexible rolling of aluminium. Tribol. Int. 2020, 151, 106378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Kamali, H.; Huo, M.; Lin, F.; Huang, S.; Huang, H.; Jiao, S.; Xing, Z.; Jiang, Z. Eco-friendly water-based nanolubricants for industrial-scale hot steel rolling. Lubricants 2020, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Jia, F.; Zhao, J.; Huang, S.; Wang, L.; Jiao, S.; Huang, H.; Jiang, Z. Effect of water-based nanolubricant containing nano-TiO2 on friction and wear behaviour of chrome steel at ambient and elevated temperatures. Wear 2019, 426, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirizly, A.; Lenard, J.G. The effect of lubrication on mill loads during hot rolling of low carbon steel strips. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2000, 97, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Zhao, J.; Wu, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Jiao, S.; Wang, X.; Zhou, C.; Jiang, Z. Effects of oil-in-water based nanolubricant containing TiO2 nanoparticles in hot rolling of 304 stainless steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 262, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Jiang, B.; He, J.; Xia, X.; Jiang, Z.; Dai, J.; Pan, F. Effect of SiO2 nanoparticles as lubricating oil additives on the cold-rolling of AZ31 magnesium alloy sheet. Mater. Res. Innov. 2015, 19, S127–S132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Ma, X.; Ma, L.; Zhou, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, J. A study on the lubrication effects of nano-TiO2 additive water-based lubricants during rolling of ferritic stainless steel strips. Lubr. Sci. 2023, 35, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Ma, X. Study on the tribological behaviour of nanolubricants during micro rolling of copper foils. Materials 2022, 15, 2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Zhao, J.; Xia, W.; Cheng, X.; He, A.; Yun, J.H.; Wang, L.; Huang, H.; Jiao, S.; Huang, L. A study of the tribological behaviour of TiO2 nano-additive water-based lubricants. Tribol. Int. 2017, 109, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Dang, S.; Jiang, B.; Xiang, L.; Zhou, S.; Sheng, H.; Yang, T.; Pan, F. Tribological performances of SiO2/graphene combinations as water-based lubricant additives for magnesium alloy rolling. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 475, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, A.; Wu, C.; Li, W. Tribological performance of silicone oil based Al2O3 nanolubricant for an Mg alloy subjected to sliding at elevated temperatures. Tribol. Int. 2022, 175, 107779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürgenç, T. Hybrid h-BN/ZnO Nanolubricant Additives in 5W-30 Engine Oil for Enhanced Tribological Performance of Magnesium Alloys. Lubricants 2025, 13, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Wang, Q.; Wu, H. Establishment and numerical analysis of rolling force model based on dynamic roll gap. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Hwang, Y.; Cheong, S.; Choi, Y.; Kwon, L.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.H. Understanding the role of nanoparticles in nano-oil lubrication. Tribol. Lett. 2009, 35, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Dang, H. Surface-modification in situ of nano-SiO2 and its structure and tribological properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 252, 7856–7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhao, J.; Luo, L.; Huang, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Jiao, S.; Huang, H.; Jiang, Z. Performance evaluation and lubrication mechanism of water-based nanolubricants containing nano-TiO2 in hot steel rolling. Lubricants 2018, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Huo, M.; Ma, X.; Jia, F.; Jiang, Z. Study on edge cracking of copper foils in micro rolling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 747, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, T.; Mendelsohn, D. On the effect of crack face contact and friction due to fracture surface roughness in edge cracks subjected to external shear. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1988, 31, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.-S.; Hong, J.-P.; Kim, M.; Park, Y.-C.; Lee, S.-M.; Cho, D.-Y.; Cho, C.-H. Study on rolling defects of Al-Mg alloys with high Mg content in normal rolling and cross-rolling processes. Materials 2023, 16, 6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, C.; Lenard, J. Friction in cold rolling of a low carbon steel with lubricants. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2000, 99, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Gao, Z.; Wang, X. Suppression strategies of chatter in the cold rolling by regulating interface friction based on dynamic stability analysis. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 3743–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.-Y.; Wei, Z. Edge cracking behavior of copper foil in asymmetrical micro-rolling. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2025, 35, 1634–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiantara, I.P.; Fatimah, S.; Bahanan, W.; Kang, J.-H.; Ko, Y.G. Impact of Lubrication on Shear Deformation During Asymmetrical Rolling: A Viscoplastic Analysis of Slip System Activity Using an Affine Linearization Scheme. Lubricants 2025, 13, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Z.; Han, C. A Study on the Surfactant and Tribological Properties of Water-Based Nano-Rolling Lubricants on Non-Ferrous Metal Surfaces. Lubricants 2025, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhao, J.; Xia, W.; Cheng, X.; He, A.; Yun, J.H.; Wang, L.; Huang, H.; Jiao, S.; Huang, L. Analysis of TiO2 nano-additive water-based lubricants in hot rolling of microalloyed steel. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2017, 27, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Ma, L.; Ma, X.; Zhou, C.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, J. Tribological Properties and Lubrication Mechanisms of Water-Based Nanolubricants Containing TiO2 Nanoparticles during Micro Rolling of Titanium Foils. Materials 2023, 17, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, D.; Zheng, S.; Wang, Y.; Guan, R.; Cao, B. The tribology properties of alumina/silica composite nanoparticles as lubricant additives. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 5720–5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, X.; Qin, B.; Xing, D.; Guo, Y.; Fan, R. Investigation of the mending effect and mechanism of copper nano-particles on a tribologically stressed surface. Tribol. Lett. 2004, 17, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Mg | Cu | Ca | Mn | Si | Al | Zn | Cr | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZ31B Mg alloy | Others | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.8 | 0.07 | 3.2 | 1.2 | - | - |

| 5052 Al alloy | 2.2–2.8 | 0.1 | - | 0.1 | 0.25 | Others | 0.1 | 0.15–0.35 | 0.4 |

| Reduction Rate | 32% | 37% | 42% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry | 199.4 | 288.2 | 628.8 |

| Lubricant | 0 | 64.4 | 114.4 |

| Reduction Rate | 32% | 37% | 42% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry | 33.6 | 160.1 | 275.1 |

| Lubricant | 0 | 7.5 | 32.9 |

| Reduction Rate | 32% | 37% | 42% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry | 4 | 3 | 1.5 |

| Lubricant | 0 | 1 | 2.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, G.; Wang, N.; Li, Z.; Du, S.; Li, Z. Influence of Nano-Lubricants on Edge Cracking and Surface Quality of Rolled Mg/Al Composite Foils. Lubricants 2025, 13, 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120518

Feng G, Wang N, Li Z, Du S, Li Z. Influence of Nano-Lubricants on Edge Cracking and Surface Quality of Rolled Mg/Al Composite Foils. Lubricants. 2025; 13(12):518. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120518

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Guang, Ning Wang, Zhongxiang Li, Shaoyong Du, and Zhaopeng Li. 2025. "Influence of Nano-Lubricants on Edge Cracking and Surface Quality of Rolled Mg/Al Composite Foils" Lubricants 13, no. 12: 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120518

APA StyleFeng, G., Wang, N., Li, Z., Du, S., & Li, Z. (2025). Influence of Nano-Lubricants on Edge Cracking and Surface Quality of Rolled Mg/Al Composite Foils. Lubricants, 13(12), 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants13120518