Patient Perceptions of Embryo Visualisation and Ultrasound-Guided Embryo Transfer During IVF: A Descriptive Observational Study

Abstract

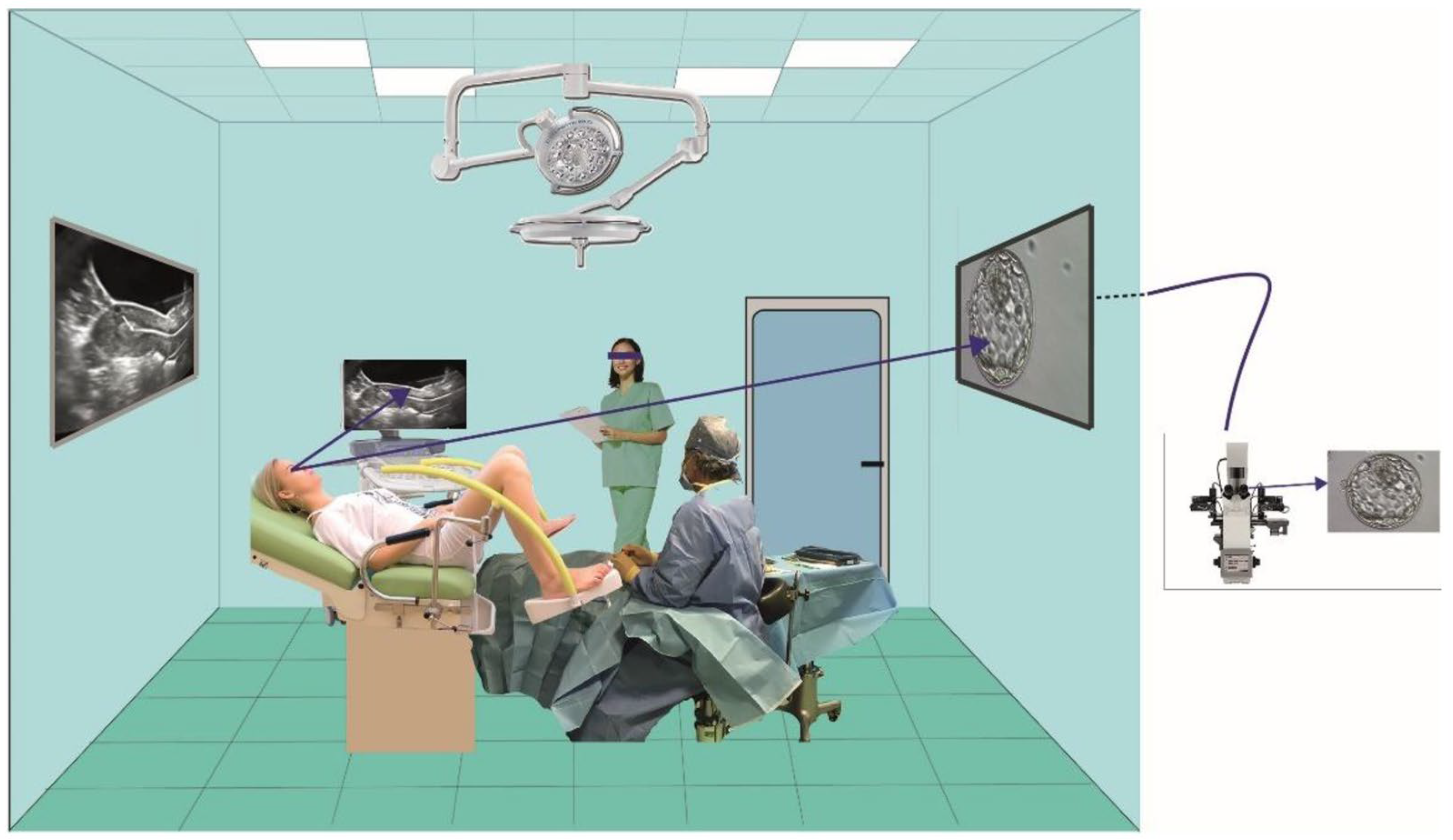

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

- Do you prefer always interacting with the same doctor rather than seeing a different doctor each time?

- Would you be more satisfied if the gynaecologist or embryologist, besides providing the embryo culture results, showed you the embryo images on a screen in the transfer room in real time before the transfer?

- Does the ultrasound during ultrasound-guided transfer cause you discomfort?

- Does the performance of ultrasound-guided embryo transfer make you feel more secure?

- Does viewing the embryos on a screen and seeing the ultrasound-guided transfer on another screen help you face the transfer more calmly?

- Do you believe that ultrasound-guided transfer and viewing your embryos during the procedure may infringe on your privacy?

- Do you consider it important for your partner to be present during the transfer?

- Do you think the midwife’s presence in the transfer room, in addition to the possible presence of your partner, infringes on your privacy?

2.3. Patient’s Experience

- Very much;

- Quite a bit;

- Moderately;

- A little;

- Not at all.

- Detection of nuances in responses;

- Ease of understanding and standardisation;

- Quantification of subjective experiences;

- Detection of variability in experiences;

- Validity and reliability.

- Strict anonymity: Ensuring that responses were completely anonymous and that no one (not even the centre staff) could associate reactions with a specific patient helped reduce the risk of answers being influenced by the desire to please the researchers or medical staff.

- Confidentiality statement: We strengthened communication regarding the confidentiality of the information, explaining that responses would not affect the treatment or care received. Thus, we reduced bias related to fear of external judgment.

2.4. Organisational Determinants

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Descriptive Analysis of Responses

2.7. Correlation Analysis Between Questions and Significance

2.8. Analysis of Differences Between Responses to Multiple Questions

2.9. Reliability Analysis of the Scale

2.10. Factor Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Organisational and Patient Determinants

3.2. Reliability Analysis of the Scale

4. Discussion

4.1. Patient-Centred Care and the Doctor–Patient Relationship

4.2. Ultrasound-Guided Transfer: Precision and Psychological Comfort

4.3. Privacy and Confidentiality: A Delicate Balance

4.4. Embryo Visualisation: The Effect of Visual Transparency

4.5. Partner Presence: Emotional Support and Social Context

4.6. Reliability of Results and Correlations

4.7. Implications for Clinical Practice

4.8. Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Verhaak, C.M.; Smeenk, J.M.; Evers, A.W.; Kremer, J.A.; Kraaimaat, F.W. Psychological outcomes in women undergoing fertility treatment: A systematic literature review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2020, 26, 58–75. [Google Scholar]

- Eugster, A.; Heier, H.; Kjær, T.M.; Madsen, L.B. Mental health in women undergoing in vitro fertilisation: A longitudinal analysis. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 43, 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau, T.M.; Domar, A.D.; Sabini, E.A. Stress and coping in women undergoing in vitro fertilisation: A meta-analysis. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 1225–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, J.; Bunting, L.; Collins, J. Psychological and relational impacts of infertility and assisted reproduction: An update. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 836–848. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Dougall, K.; Wilschut, J.; van de Wiel, H. Psychological distress in fertility treatment patients: A cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Bengoa, R.; Kawar, R.; Key, P.; Leatherman, S.; Massoud, R.; Saturno, P. Quality of Care: A Process for Making Strategic Choices in Health Systems; World Health Organization Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Peddie, V.; Fishel, S. Patient-centred care in fertility treatment: A critical review. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar]

- Klemetti, R.; Raitanen, J. The importance of patient-centred communication in fertility treatment: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 252, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Gleicher, N.; Barad, D.H. The role of patient-centred care in infertility treatment outcomes. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2017, 34, 859–865. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, L.; Millar, A. Reframing fertility care: The centrality of patient empowerment and choice. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Hammarberg, K.; McDonald, H. Women's experiences of infertility and assisted reproductive technologies: A patient-centred perspective. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau, T.M.; Domar, A.D. Psychological aspects of fertility treatment: The importance of patient-centered care. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tuil, W.S.; ten Hoopen, A.J.; Braat, D.D.; de Vries Robbe, P.F.; Kremer, J.A. Patient-centred care: Using online personal medical records in IVF practice. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 2955–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mourad, S.M.; Nelen, W.L.D.M.; Akkermans, R.P.; Vollebergh, J.H.; Grol, R.P.; Hermens, R.P.; Kremer, J.A. Determinants of patients’ experiences and satisfaction with fertility care. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 1254–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verberg, M.F.G.; Eijkemans, M.J.C.; Heijnen, E.M.E.W.; Broekmans, F.J.; de Klerk, C.; Fauser, B.C.J.M.; Macklon, N.S. Why do couples drop out of IVF treatment? A prospective cohort study. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 2050–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoul, J.; Nargund, G.; Lisi, F. Ultrasound-guided embryo transfer in assisted reproduction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2019, 25, 308–318. [Google Scholar]

- Malvasi, A.; Damiani, G.R.; Edoardo, D.N.; Vitagliano, A.; Dellino, M.; Achiron, R.; Ioannis, K.; Vimercati, A.; Gaetani, M.; Cicinelli, E.; et al. Intrapartum ultrasound and mother acceptance: A study with informed consent and questionnaire. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. X 2023, 20, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souter, V.L.; Penney, G.; Hopton, J.L.; Templeton, A.A. Patient satisfaction with the management of infertility. Hum. Reprod. 1998, 13, 1831–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancet, E.A.; Nelen, W.L.; Sermeus, W.; De Leeuw, L.; Kremer, J.A.; D‘Hooghe, T.M. The patients’ perspective on fertility care: A systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2010, 16, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Empel, I.W.; Nelen, W.L.; Tepe, E.T.; van Laarhoven, E.A.; Verhaak, C.M.; Kremer, J.A. Weaknesses, strengths and needs in fertility care according to patients. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousineau, T.M.; Domar, A.D. Psychological impact of infertility. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2007, 21, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, G.J.; Meterko, M.; Desai, K.R. Patient satisfaction with hospital care: Effects of demographic and institutional characteristics. Med. Care. 2000, 38, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammarberg, K.; Astbury, J.; Baker, H. Women‘s experience of IVF: A follow-up study. Hum. Reprod. 2001, 16, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, R.; Gage, H.; Hampson, S.; Hart, J.; Kimber, A.; Storey, L.; Thomas, H. The measurement of satisfaction with healthcare: Implications for practice from a systematic literature review. Health. Technol. Assess. 2002, 32, 1–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L.; Holstein, B.E.; Boivin, J.; Sangren, H.; Tjornhoj-Thomsen, T.; Blaabjerg, J.; Hald, F.; Andersen, A.N.; Rasmussen, P.E. Patients’ attitudes to medical and psychosocial aspects of care in fertility clinics: Findings from the Copenhagen Multi-centre Psychosocial Infertility (COMPI) Research Programme. Hum. Reprod. 2003, 18, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, B.Z.; Harkness, E.; Ernst, E.; Georgiou, A.; Kleijnen, J. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: A systematic review. Lancet 2001, 357, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redshaw, M.; Hockley, C.; Davidson, L.L. A qualitative study of the experience of treatment for infertility among women who successfully became pregnant. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabel, L.L.; Lucas, J.B.; Westbury, R.C. Why do patients continue to see the same physician? Fam. Pract. Res. J. 1993, 13, 133–147. [Google Scholar]

- Saultz, J.W.; Albedaiwi, W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: A critical review. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004, 2, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Gray, D.J.; Sidaway-Lee, K.; White, E.; Thorne, A.; Evans, P.H. Continuity of care with doctors-a matter of life and death? A systematic review of continuity of care and mortality. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.P.; Shaver, P.R.; Wrightsman, L.S. Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- James, C.A. The nursing role in assisted reproductive technologies. NAACOG's Clin. Issues Perinat. Women's Health Nurs. 1992, 3, 328–334. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A.; Mittelstaedt, M.E.; Wagner, C. A survey of nurses who practice in infertility settings. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2005, 34, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zivaridelavar, M.; Kazemi, A.; Kheirabadi, G.R. The effect of assisted reproduction treatment on mental health in fertile women. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2016, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schmidt, L.; Holstein, B.E.; Christensen, U.; Boivin, J. The impact of infertility on quality of life and mental health. Hum. Reprod. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Balen, A.H.; Hiam, C.; Ruiter, L. Psychological outcomes in women undergoing fertility treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, M.; Diedrich, K.; Langen, D. The impact of IVF on the psychological well-being of women. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, R.; Doherty, M. Fertility treatment and emotional stress: A systematic literature review. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stanhiser, J.; Steiner, A.Z. Psychosocial Aspects of Fertility and Assisted Reproductive Technology. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. 2018, 45, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayling, K.; Fairclough, L.; Tighe, P.; Todd, I.; Halliday, V.; Garibaldi, J.; Royal, S.; Hamed, A.; Buchanan, H.; Vedhara, K. Positive mood on the day of influenza vaccination predicts vaccine effectiveness: A prospective observational cohort study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018, 67, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, H.T.; Clark, M.S.; Pereira Gray, D.; Tsai, F.F.; Brown, J.B.; Stewart, M.; Underwood, L.G. Measuring responsiveness in the therapeutic relationship: A patient perspective. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 2008, 30, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, M.; Vitagliano, A.; Di Giovanni, M.V.; Laganà, A.S.; Vitale, S.G.; Blaganje, M.; Drusany Starič, K.; Borut, K.; Patrelli, T.S.; Noventa, M. Ultrasound-guided embryo transfer: Summary of the evidence and new perspectives. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2018, 36, 524–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, D.M.; Dassunção, L.A.; Vieira, C.V.; Barbosa, M.A.; Coelho Neto, M.A.; Nastri, C.O.; Martins, W.P. Ultrasound guidance during embryo transfer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 45, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larue, L.; Keromnes, G.; Massari, A.; Roche, C.; Moulin, J.; Gronier, H.; Bouret, D.; Cassuto, N.G.; Ayel, J.P. Transvaginal ultra-sound-guided embryo transfer in IVF. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 46, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Group | Control Group | Student’s t-Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N° | 200 | 3174 | |

| Mean Age | 35.27 | 35.55 | n.s. |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 64.7% | 63.5% | n.s. |

| Cohabiting | 35.3% | 36.5% | n.s. |

| Duration of Infertility | 2.3 | 2.5 | n.s. |

| Education Level | |||

| Primary School | 3% | 3.3% | n.s. |

| Secondary School | 17% | 16.8% | n.s. |

| High School | 53.9% | 53.4% | n.s. |

| University Degree | 26.1% | 26.5% | n.s. |

| Occupation | |||

| Employed / Worker | 37.5% | 36.9% | n.s. |

| Housewife | 24.7% | 25.4% | n.s. |

| Professional | 21.7% | 20.9% | n.s. |

| Entrepreneur | 9.9% | 10.0% | n.s. |

| Unemployed | 5.7% | 6.1% | n.s. |

| Student | 0.6% | 0.7% | n.s. |

| Question | Likert Scale | Responses | % | Mean | Median | SD | Chi-Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Is it better to interact always with the same doctor rather than with a different one each time? | 1. Very much 2. Quite 3. Moderately 4. A little 5. Not at all | 168 21 2 3 6 | 84 10.5 1 1.5 3 | 1.29 | 1 | 0.824 | 143.1, p < 0.0001 |

| 2. Are you more satisfied if the gynaecologist or embryologist shows you the images of the embryos to be transferred in real time during the transfer procedure? | 1. Very much 2. Quite 3. Moderately 4. A little 5. Not at all | 170 20 10 0 0 | 85 10 5 0 0 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.511 | 167.1, p < 0.0001 |

| 3. Does the ultrasound during the guided embryo transfer cause discomfort? | 1. Very much 2. Quite 3. Moderately 4. A little 5. Not at all | 5 2 6 15 172 | 2.5 1 3 7.5 86 | 1.265 | 1 | 0.786 | 180.3, p < 0.0001 |

| 4. Does the use of ultrasound during the embryo transfer procedure make you feel more at ease? | 1. Very much 2. Quite 3. Moderately 4. A little 5. Not at all | 170 16 9 1 4 | 85 8 4.5 0.5 2 | 1.265 | 1 | 0.747 | 143.1, p < 0.0001 |

| 5. Do you feel that viewing the embryos along with ultrasound during the transfer helps you face the procedure with more calmness? | 1. Very much 2. Quite 3. Moderately 4. A little 5. Not at all | 183 15 1 1 0 | 91.5 7.5 0.5 0.5 0 | 1.075 | 1 | 0.264 | 176.9, p < 0.0001 |

| 6. Do you feel that the ultrasound and viewing your embryos during the transfer could violate your privacy? | 1. Very much 2. Quite 3. Moderately 4. A little 5. Not at all | 0 0 2 1 197 | 0 0 1 0.5 98.5 | 1.005 | 1 | 0.070 | 255.3, p < 0.0001 |

| 7. Do you consider it important that your partner is present during the transfer? | 1. Very much 2. Quite 3. Moderately 4. A little 5. Not at all | 119 9 2 13 57 | 59.5 4.5 1 6.5 28.5 | 1.05 | 1 | 0.240 | 110.0, p < 0.0001 |

| 8. In the transfer room, does the presence of the midwife (other than your husband) interfere with your privacy? | 1. Very much 2. Quite 3. Moderately 4. A little 5. Not at all | 1 2 0 3 194 | 0.5 1 0 1.5 97 | 1.025 | 1 | 0.156 | 244.7, p < 0.0001 |

| Spearman r | Question 2 | Question 4 | Question 5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| r | 0.007315 | 0.01406 | 0.03239 |

| 95% confidence interval | −0.1356 to 0.1499 | −0.1290 to 0.1565 | −0.1109 to 0.1744 |

| p value | |||

| p (two-tailed) | 0.918 | 0.843 | 0.649 |

| p value summary | ns | ns | ns |

| Exact or approximate p value? | Approximate | Approximate | Approximate |

| Significant? (alpha = 0.05) | No | No | No |

| Number of XY pairs | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Kruskal–Wallis Test | p-Value | Approximate p-Value? | Medians Vary Significantly (p < 0.05)? | Number of Groups | Kruskal–Wallis Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.0001 | Approximate | Yes | 8 | 67.99 |

| Question | Initial Eigenvalues | Loading Sums of Extraction Squares | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | % Cumulative | Total | % of Variance | % Cumulative | |

| 1 | 1.296 | 16.195 | 16.195 | 1.296 | 16.195 | 16.195 |

| 2 | 1.126 | 14.073 | 30.267 | 1.126 | 14.073 | 30.267 |

| 3 | 1.051 | 13.136 | 43.404 | 1.051 | 13.136 | 43.404 |

| 4 | 1.024 | 12.797 | 56.201 | 1.024 | 12.797 | 56.201 |

| 5 | 0.967 | 12.087 | 68.288 | |||

| 6 | 0.943 | 11.788 | 80.075 | |||

| 7 | 0.884 | 11.053 | 91.129 | |||

| 8 | 0.710 | 8.871 | 100.000 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baldini, G.M.; Lot, D.; Malvasi, A.; Laganà, A.S.; Marino, A.A.; Baldini, D.; Trojano, G. Patient Perceptions of Embryo Visualisation and Ultrasound-Guided Embryo Transfer During IVF: A Descriptive Observational Study. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15080374

Baldini GM, Lot D, Malvasi A, Laganà AS, Marino AA, Baldini D, Trojano G. Patient Perceptions of Embryo Visualisation and Ultrasound-Guided Embryo Transfer During IVF: A Descriptive Observational Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(8):374. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15080374

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaldini, Giorgio Maria, Dario Lot, Antonio Malvasi, Antonio Simone Laganà, Angelo Alessandro Marino, Domenico Baldini, and Giuseppe Trojano. 2025. "Patient Perceptions of Embryo Visualisation and Ultrasound-Guided Embryo Transfer During IVF: A Descriptive Observational Study" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 8: 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15080374

APA StyleBaldini, G. M., Lot, D., Malvasi, A., Laganà, A. S., Marino, A. A., Baldini, D., & Trojano, G. (2025). Patient Perceptions of Embryo Visualisation and Ultrasound-Guided Embryo Transfer During IVF: A Descriptive Observational Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(8), 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15080374