Implementation of Polygenic Risk Stratification and Genomic Counseling in Colombia: An Embedded Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting: “Soy Generación” Study

Variables and Data Collection

2.2. Polygenic Risk Score Development and Classification

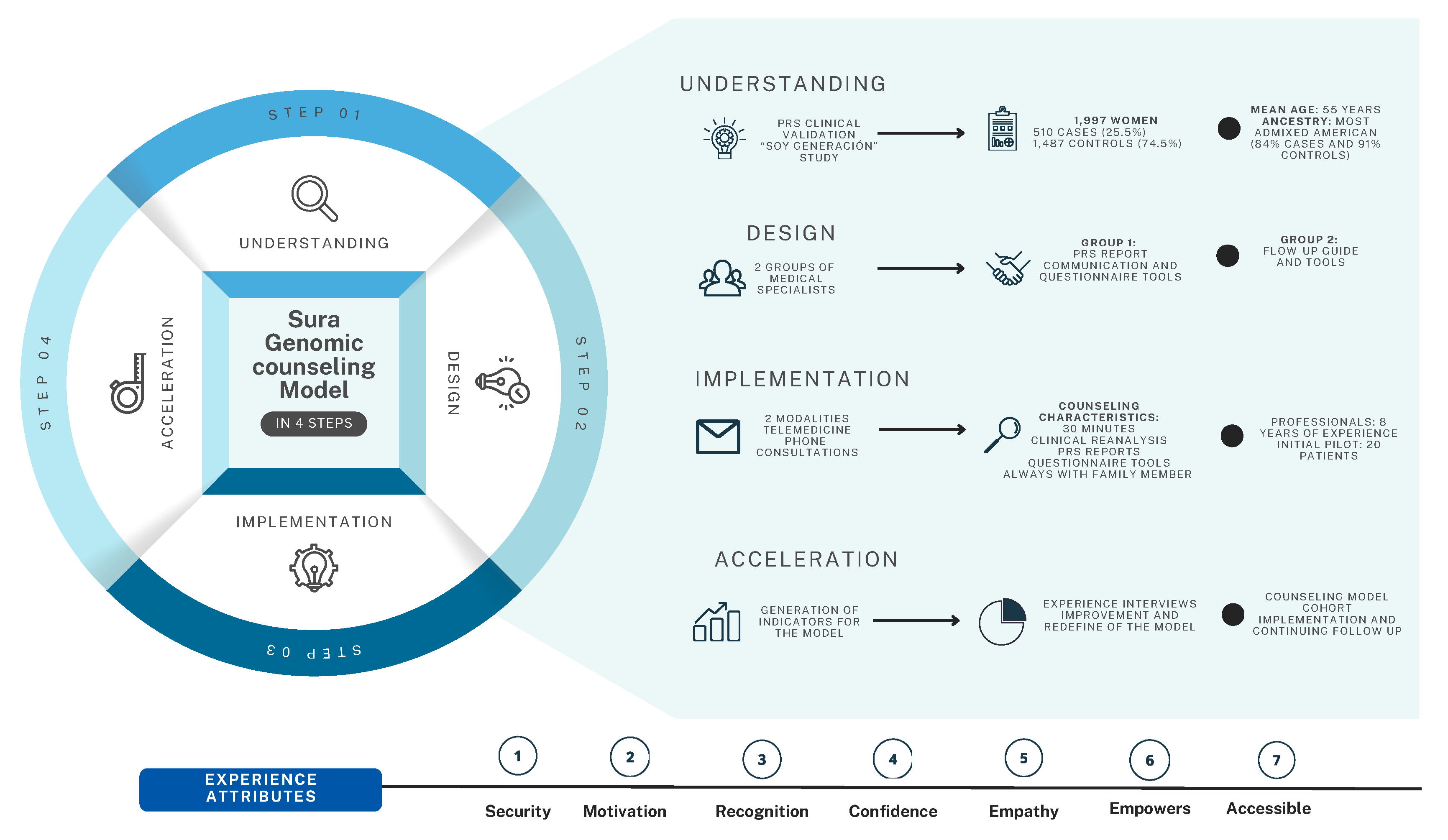

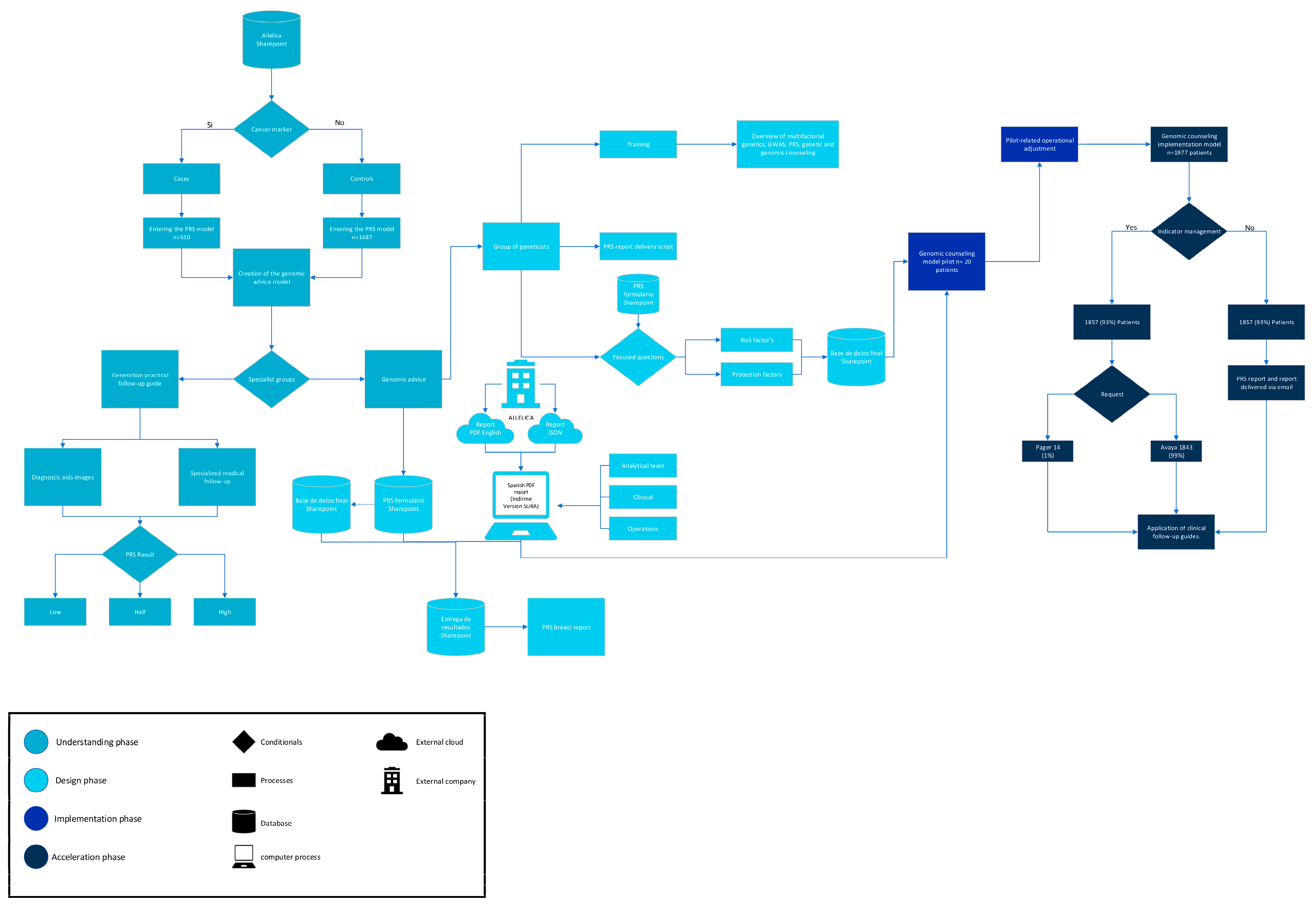

2.3. Genomic Counseling Model

2.3.1. Understanding Phase

2.3.2. Design Phase

2.3.3. Implementation Phase

2.4. Clinical Follow-Up and Patient Experience

2.4.1. Clinical Follow-Up

2.4.2. Patient Experience

2.4.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Implementation Outcomes

3.2. Clinical Follow-Up and Patient Experience

3.2.1. Communication Effectiveness

“I have two challenges: letting go of paradigms and many thoughts. When I bring an important piece of genetic health information from my parents, it acts as a warning signal—something to pay attention to. It’s a chance to prioritize which health conditions I need to address first. Being part of this process, which has the potential to change the lives of many women, feels like a beautiful gift. It’s helped me change my physical activity routine. While at times it brings anxiety and less pleasant emotions, it also offers the opportunity to think differently, to face fears and anxieties, and to see these as part of the process.”Participant 20

“It’s been excellent—very good and reassuring. For context, someone in my family passed away from breast cancer that metastasized. We lived through the entire process without any improvement, and it left a permanent mark on me. When I was called to participate, I felt a little scared and thought, ‘Oh my God, could something bad happen?’ But everything turned out to be a blessing. Being part of this model has made me more conscious. It became a personal challenge to make changes. With the ‘Vive Más’ platform, I started moving more, dancing, and seeking change. Today, I feel at peace after this test.”Participant 2

3.2.2. Patient Support

“When I was invited to be part of the model, I thought, ‘Why me? Did they find something?’ But when they explained it to me, I realized what a gift the company was giving us.”Participant 30

“The clarity of the explanations was remarkable. They told us, ‘This process is to identify the probability of risk.’ The specialized exams and the warmth of everyone involved in the process made me feel valued. On the day of the tests, I felt like a queen—it has such an integral approach.”Participant 9

“I feel reassured, knowing this is about prevention and care. The genetic percentage and the sporadic percentage were explained so clearly. I feel accompanied by experts who guide me and show progress every step of the way.”Participant 5

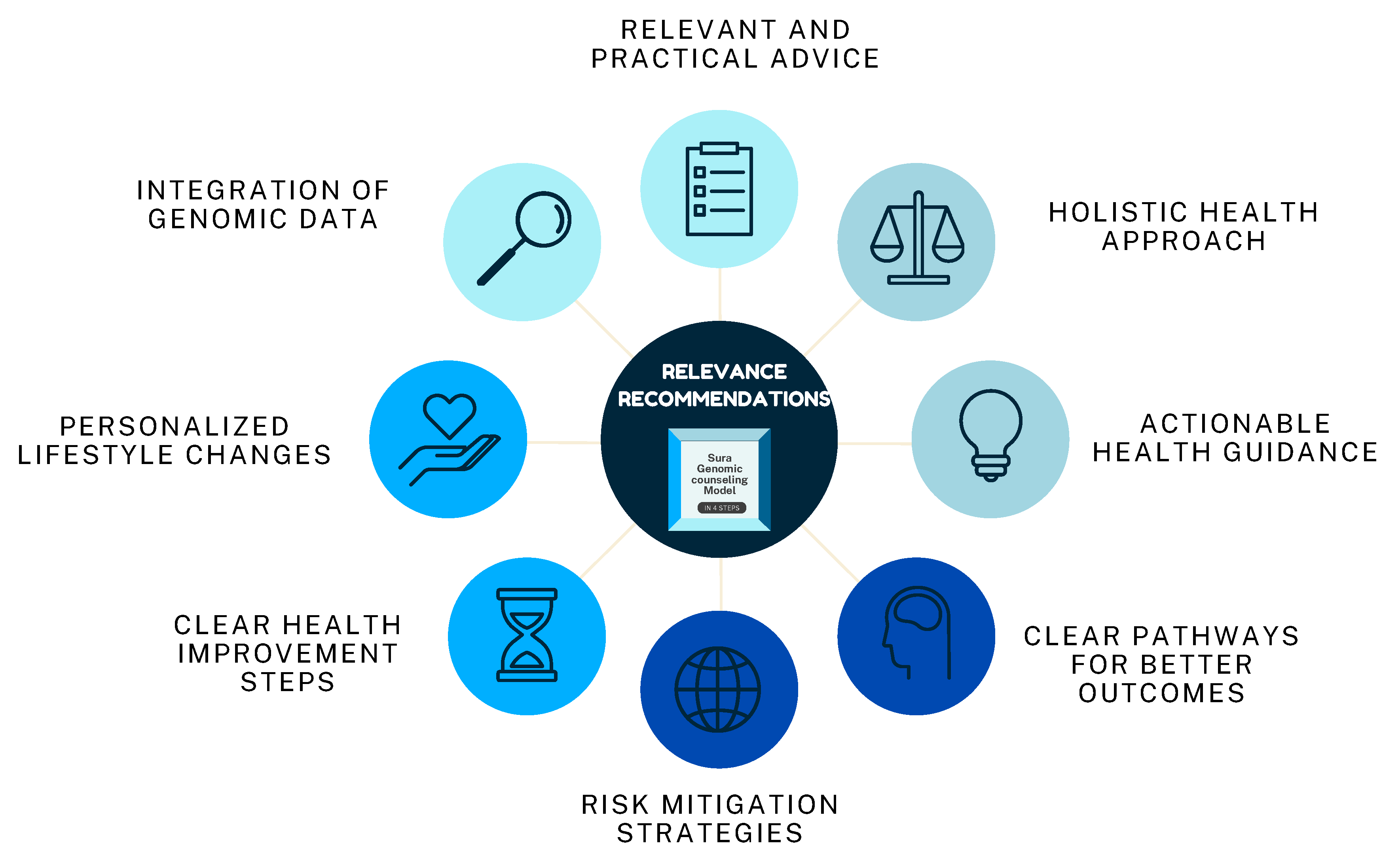

3.2.3. Relevance of Recommendations

3.2.4. Accessibility of Counseling

“I felt the phone session was helpful, but a video call would have felt more connected”Participant 10

“Telemedicine made it easy to focus on my health without worrying about logistics”.Participant 3

3.2.5. Overall Satisfaction

“The whole process was seamless; from the moment I was invited to join until the final step. It felt very well-coordinated”.Participant 18

“I felt like I was really part of the process and that I had all the information I needed to take care of myself”.Participant 22

“It gave me the tools to take proactive steps, knowing both my genetic risk and what I can do about it”.Participant 40

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRS | Polygenic risk score |

| LMICs | Low-and middle-income countries |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| GCIRS | Genetic Counseling Intervention Reporting Standards. |

| WISDOM | Women Informed to Screen Depending on Measures of Risk |

| MyPeBS | My Personal Breast Screening |

| CRF | Digital Case Report form |

| BIRADS | Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Cancer Burden Growing, Amidst Mounting Need for Services. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/zh/news/item/01-02-2024-global-cancer-burden-growing--amidst-mounting-need-for-services (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pharoah, P.D.P.; Antoniou, A.C.; Easton, D.F.; Ponder, B.A.J.; Health, P.; Care, P. Polygenes, Risk Prediction, and Targeted Prevention of Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2796–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavaddat, N.; Michailidou, K.; Dennis, J.; Lush, M.; Fachal, L.; Lee, A.; Tyrer, J.P.; Chen, T.-H.; Wang, Q.; Bolla, M.K.; et al. Polygenic Risk Scores for Prediction of Breast Cancer and Breast Cancer Subtypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 104, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torkamani, A.; Wineinger, N.E.; Topol, E.J. The personal and clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, S.A.; Abraham, G.; Inouye, M. Towards clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, R133–R142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shieh, Y.; Hu, D.; Ma, L.; Huntsman, S.; Gard, C.C.; Leung, J.W.T.; Tice, J.A.; Vachon, C.M.; Cummings, S.R.; Kerlikowske, K.; et al. Breast cancer risk prediction using a clinical risk model and polygenic risk score. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 159, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, S.P.; Kaur, A.S.; Vegunta, S. Association Between Lifestyle Changes, Mammographic Breast Density, and Breast Cancer. Oncologist 2022, 27, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ho, R.C.M.; Mak, A. Interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and soluble interleukin-2 receptors (sIL-2R) are elevated in patients with major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 139, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Zeinomar, N.; Chung, W.K.; Kiryluk, K.; Gharavi, A.G.; Hripcsak, G.; Crew, K.D.; Shang, N.; Khan, A.; Fasel, D.; et al. Generalizability of Polygenic Risk Scores for Breast Cancer among Women with European, African, and Latinx Ancestry. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2119084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ormond, K.E. From genetic counseling to “genomic counseling”. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2013, 1, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, A.; Thirlaway, K. “Genomic counseling”? Genetic counseling in the genomic era. Genome Med. 2011, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooker, G.W.; Ormond, K.E.; Sweet, K.; Biesecker, B.B. Teaching genomic counseling: Preparing the genetic counseling workforce for the genomic era. J. Genet. Couns. 2014, 23, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz Caro, D.; Simone, L. The role of the Latin American Professional Society of Genetic Counseling (SPLAGen): Advancing genetic counseling in Latin America. Genet. Med. Open 2024, 2, 101870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco Parra, H.M.; Cardona, D.S.; Buitrago, C.A.; Vanegas, M.N.; Hincapié, S.G.; Jaramillo, C.J.; Cock-Rada, A.M.; Benavides Duque, C.; Piedrahita, C.P.; Bustamante, C.; et al. Clinical validation of an integrated risk assessment test incorporating genomic and non-genomic data for sporadic breast cancer in Colombia. Front. Genet. 2025, 16, 1556907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busby, G.B.; Kulm, S.; Bolli, A.; Kintzle, J.; Di Domenico, P.; Bottà, G. Ancestry-specific polygenic risk scores are risk enhancers for clinical cardiovascular disease assessments. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooker, G.W.; Babu, D.; Myers, M.; Zierhut, H.; McAllister, M. Standards for the Reporting of Genetic Counseling Interventions in Research and Other Studies (GCIRS): An NSGC Task Force Report. J. Genet. Couns. 2017, 26, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eklund, M.; Broglio, K.; Yau, C.; Connor, J.T.; Fiscalini, A.S.; Esserman, L.J. The WISDOM Personalized Breast Cancer Screening Trial: Simulation Study to Assess Potential Bias and Analytic Approaches. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018, 2, pky067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roux, A.; Cholerton, R.; Sicsic, J.; Moumjid, N.; French, D.P.; Giorgi Rossi, P.; Balleyguier, C.; Guindy, M.; Gilbert, F.J.; Burrion, J.-B.; et al. Study protocol comparing the ethical, psychological and socio-economic impact of personalised breast cancer screening to that of standard screening in the “My Personal Breast Screening” (MyPeBS) randomised clinical trial. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayudas Diagnósticas Sura (2024), Modelo de Acompañamiento de Cáncer de Mama “Seno”. Available online: https://www.epssura.com/cancer-seno (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Ayudas Diagnósticas Sura (2024). SURA SENO: Símbolo Para Hacerse el Autoexamen de Mama SURA. 2018. Available online: https://segurossura.com/co/blog/salud/seno-simbolo-para-hacerse-el-autoexamen-de-mama/ (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Ren, W.; Chen, M.; Qiao, Y.; Zhao, F. Global guidelines for breast cancer screening: A systematic review. Breast 2022, 64, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanski, A.; Hall, A.; Reiser, C.; Uttal, K.; Kuhl, A. Leadership development in genetic counseling graduate programs. J. Genet. Couns. 2024, 34, e1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, E.; Howell, S.; Evans, D.G. Polygenic risk scores and breast cancer risk prediction. Breast 2023, 67, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanes, T.; Young, M.A.; Meiser, B.; James, P.A. Clinical applications of polygenic breast cancer risk: A critical review and perspectives of an emerging field. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeyemo, A.; Balaconis, M.K.; Darnes, D.R.; Fatumo, S.; Granados Moreno, P.; Hodonsky, C.J.; Inouye, M.; Kanai, M.; Kato, K.; Knoppers, B.M.; et al. Responsible use of polygenic risk scores in the clinic: Potential benefits, risks and gaps. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1876–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfson, M.; Gribble, S.; Pashayan, N.; Easton, D.F.; Antoniou, A.C.; Lee, A.; van Katwyk, S.; Simard, J. Potential of polygenic risk scores for improving population estimates of women’s breast cancer genetic risks. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 2114–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pashayan, N.; Antoniou, A.C.; Ivanus, U.; Esserman, L.J.; Easton, D.F.; French, D.; Sroczynski, G.; Hall, P.; Cuzick, J.; Evans, D.G.; et al. Personalized early detection and prevention of breast cancer: ENVISION consensus statement. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. Nat. Res. 2020, 17, 687–705. [Google Scholar]

- Zeinomar, N.; Chung, W.K. Cases in precision medicine: The role of polygenic risk scores in breast cancer risk assessment. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Ajmi, K.; Lophatananon, A.; Mekli, K.; Ollier, W.; Muir, K.R. Association of Nongenetic Factors With Breast Cancer Risk in Genetically Predisposed Groups of Women in the UK Biobank Cohort. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khera, A.V.; Chaffin, M.; Aragam, K.G.; Haas, M.E.; Roselli, C.; Choi, S.H.; Natarajan, P.; Lander, E.S.; Lubitz, S.A.; Ellinor, P.T.; et al. Genome-wide polygenic scores for common diseases identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyu, H.H.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abay, S.M.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1859–1922. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673618323353 (accessed on 1 June 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Control, N = 1487 1 | Case, N = 510 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 69.7 (67–71) | 55 (49–61) |

| Rural or urban residence | ||

| Rural | 107 (7.2%) | 39 (7.6%) |

| Urban | 1380 (93%) | 471 (92%) |

| Socioeconomic level | ||

| 1 | 53 (3.6%) | 29 (5.7%) |

| 2 | 269 (18%) | 138 (27%) |

| 3 | 490 (33%) | 232 (45%) |

| 5 | 357 (24%) | 71 (14%) |

| 5 | 233 (16%) | 29 (5.7%) |

| 6 | 85 (5.7%) | 11 (2.2%) |

| Clinical risk classification | ||

| High (>1.9) | 144 (9.7%) | 44 (8.6%) |

| Low (<1) | 688 (46%) | 203 (40%) |

| Moderate (1.4–1.9) | 189 (13%) | 91 (18%) |

| Referent (1–1.4) | 466 (31%) | 172 (34%) |

| Breast cancer diagnosis | ||

| Biopsy | 3 (0.6%) | - |

| Breast echography | 80 (17%) | - |

| Mammography | 315 (67%) | - |

| Tomosynthesis mammography | 73 (15%) | - |

| Characteristics | High (1.9), N = 144 1 | Low (<1) N = 688 1 | Moderate (1.4–1.9) N = 189 1 | Referent (1–1.4) N = 466 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 69.9 (3.4) | 69.7 (3.5) | 69.4 (3.3) | 69.8 (3.6) | 0.4 |

| Rural or Urban residence | 0.8 | ||||

| Rural | 8 (5.6%) | 53 (7.7%) | 15 (7.9%) | 31 (6.7%) | |

| Urban | 136 (94%) | 635 (92%) | 174 (92%) | 435 (93%) | |

| Socioeconomic level | 0.9 | ||||

| 1 | 3 (2.1%) | 26 (3.8%) | 5 (2.6%) | 19 (4.1%) | |

| 2 | 23 (16%) | 125 (18%) | 35 (19%) | 86 (18%) | |

| 3 | 48 (33%) | 228 (33%) | 60 (32%) | 154 (33%) | |

| 4 | 33 (23%) | 157 (23%) | 56 (30%) | 111 (24%) | |

| 5 | 29 (20%) | 110 (16%) | 25 (13%) | 69 (15%) | |

| 6 | 8 (5.6%) | 42 (6.1%) | 8 (4.2%) | 27 (5.8%) |

| Variable | Case, N = 457 1 | Control, N = 1283 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protective factors | |||

| Diet * | 431 (94%) | 1188 (93%) | 0.2 |

| Physical activity ** | 257 (56%) | 900 (70%) | <0.001 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Diet with fats | 328 (72%) | 904 (70%) | 0.6 |

| Active smoking | 11 (2.4%) | 44 (3.4%) | 0.3 |

| Former smoker | 58 (13%) | 318 (26%) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol | 76 (17%) | 171 (13%) | 0.082 |

| Variable | OR | p-Value | IC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protective factors | |||

| Diet | 1.326 | 0.217 | (0.86, 2.113) |

| Physical Activity | 0.547 | 0.000 | (0.439, 0.682) |

| Risk Factors | |||

| Diet with Fats | 1.066 | 0.596 | (0.843, 1.353) |

| Active Smoking | 0.695 | 0.286 | (0.338, 1.308) |

| Former smoker | 0.435 | 0.000 | (0.318, 0.585) |

| Alcohol | 1.297 | 0.083 | (0.963, 1.735) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buitrago, C.A.; Naranjo Vanegas, M.; Velasco, H.M.; Cardona, D.S.; Valencia-Arango, J.P.; Franco, S.L.; Torres, L.M.; Cañaveral, J.; Silgado, D.P.; López Cáceres, A. Implementation of Polygenic Risk Stratification and Genomic Counseling in Colombia: An Embedded Mixed-Methods Study. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15080335

Buitrago CA, Naranjo Vanegas M, Velasco HM, Cardona DS, Valencia-Arango JP, Franco SL, Torres LM, Cañaveral J, Silgado DP, López Cáceres A. Implementation of Polygenic Risk Stratification and Genomic Counseling in Colombia: An Embedded Mixed-Methods Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(8):335. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15080335

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuitrago, Cesar Augusto, Melisa Naranjo Vanegas, Harvy Mauricio Velasco, Danny Styvens Cardona, Juan Pablo Valencia-Arango, Sofia Lorena Franco, Lina María Torres, Johana Cañaveral, Diana Patricia Silgado, and Andrea López Cáceres. 2025. "Implementation of Polygenic Risk Stratification and Genomic Counseling in Colombia: An Embedded Mixed-Methods Study" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 8: 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15080335

APA StyleBuitrago, C. A., Naranjo Vanegas, M., Velasco, H. M., Cardona, D. S., Valencia-Arango, J. P., Franco, S. L., Torres, L. M., Cañaveral, J., Silgado, D. P., & López Cáceres, A. (2025). Implementation of Polygenic Risk Stratification and Genomic Counseling in Colombia: An Embedded Mixed-Methods Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(8), 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15080335