Prophylactic and Therapeutic Usage of Drains in Gynecologic Oncology Procedures: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

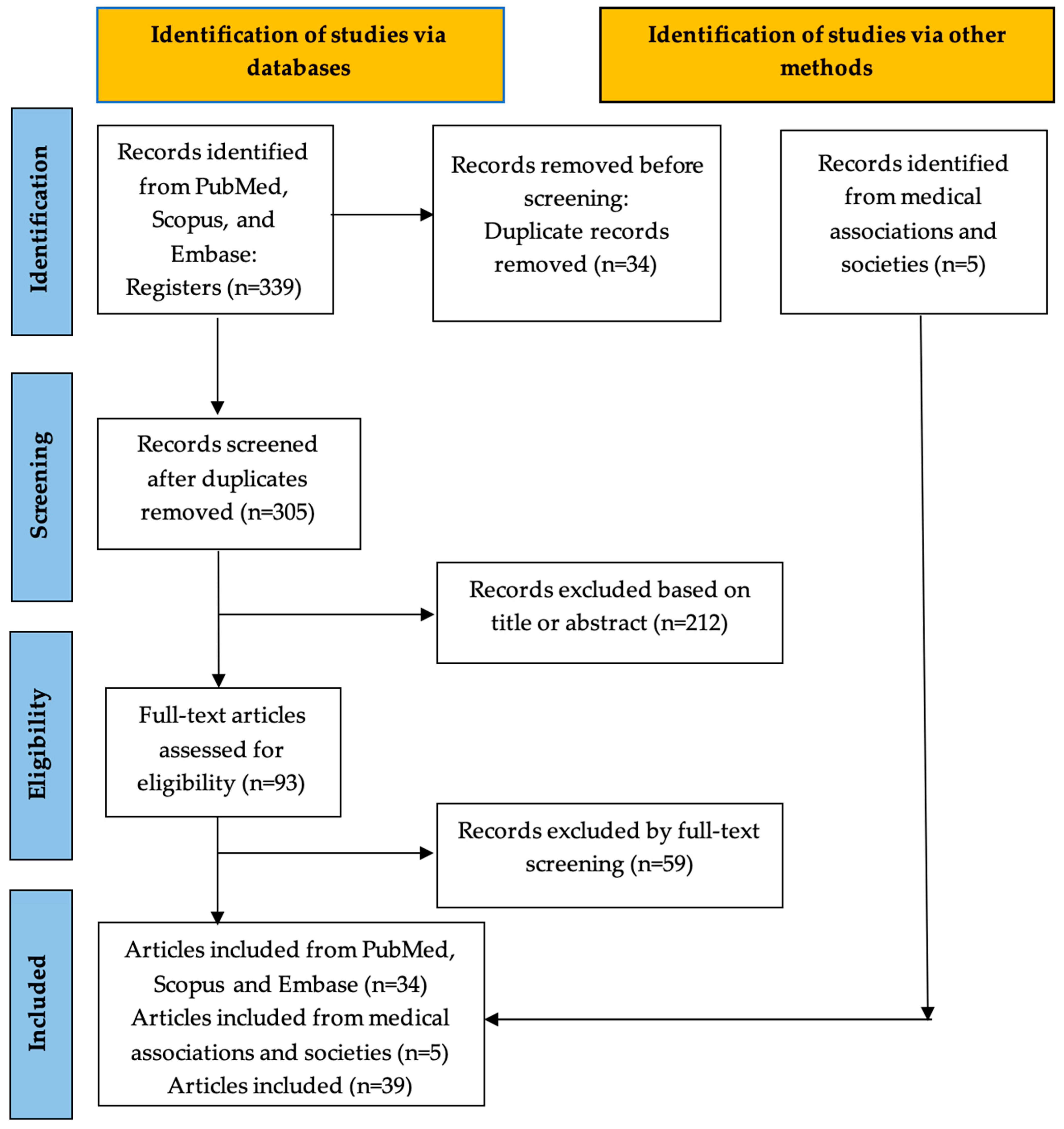

2. Materials and Methods

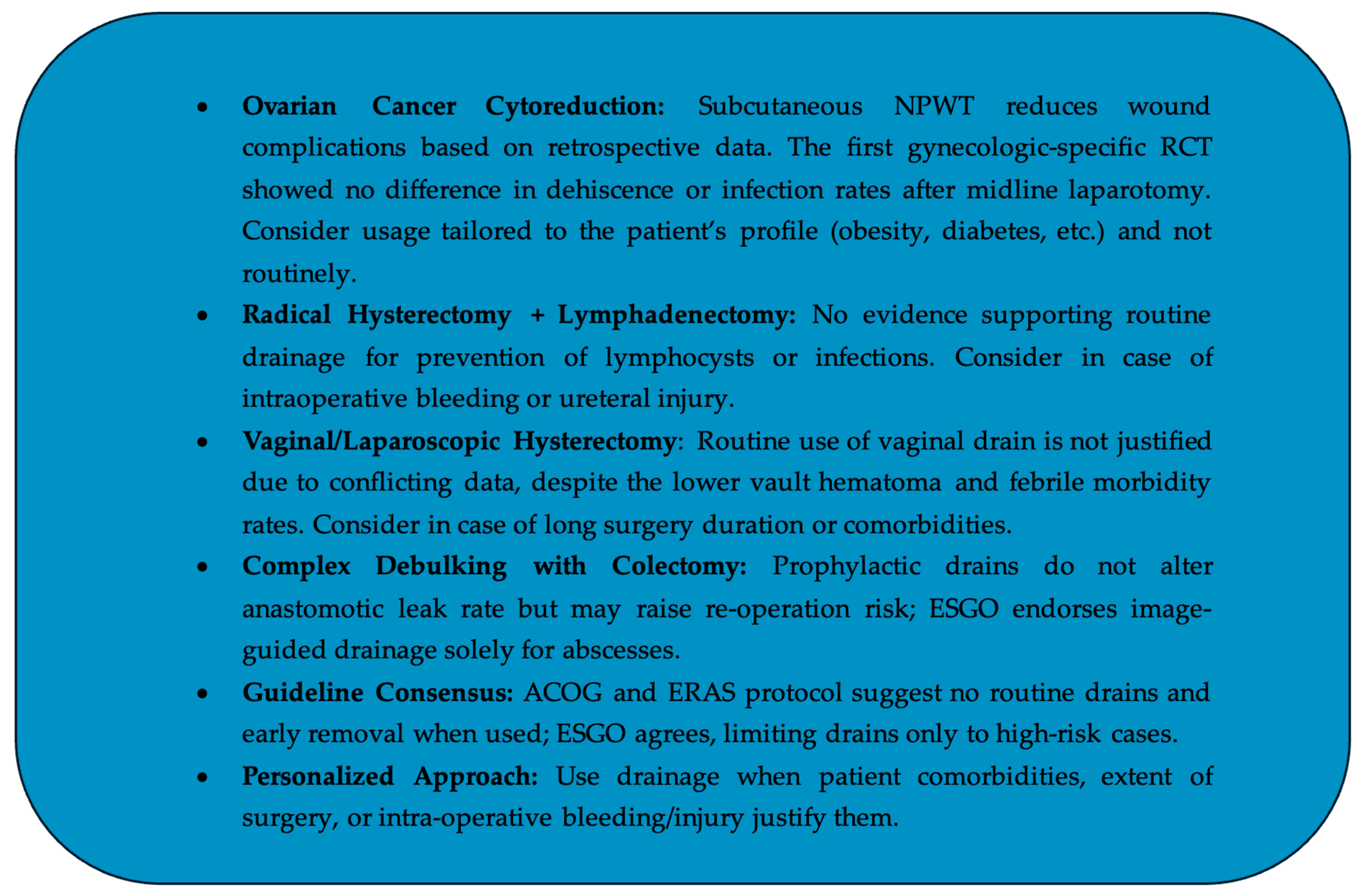

3. Drainage of Subcutaneous Wounds After Cytoreduction for Ovarian Cancer

4. Drainage Following Vaginal or Laparoscopic Hysterectomy

5. Drainage Following Radical Hysterectomy and Lymphadenectomy or Lymphadenectomy for Various Gynecological Malignancies (Pelvic and/or Para-Aortic)

6. Drainage Following Complex Debulking with Colectomy and Peritonectomy

7. Drainage Following Inguinofemoral Lymphadenectomy in Vulvar Cancer

8. Guidelines

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gilbert, A.; Ortega-Deballon, P.; Di Giacomo, G.; Cheynel, N.; Rat, P.; Facy, O. Intraperitoneal Drains Move. J. Visc. Surg. 2018, 155, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, M.; Bolton, W.; Van Duren, B.; Burke, J.; Jayne, D. Impact of Surgical Drain Output Monitoring on Patient Outcomes in Hepatopancreaticobiliary Surgery: A Systematic Review. Scand. J. Surg. 2022, 111, 14574969211030118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talwar, A.; Bansal, A.; Knight, G.; Caicedo, J.-C.; Riaz, A.; Salem, R. Adverse Events of Surgical Drain Placement: An Analysis of the NSQIP Database. Am. Surg. 2024, 90, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgari, Z.; Hosseini, R.; Rastad, H.; Hosseini, L. Does peritoneal suctiondrainage reduce pain after gynecologic laparoscopy? Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutaneous Tech. 2018, 28, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization Website. Caesarean Section Rates Continue to Rise, Amid Growing Inequalities in Access. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/ (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Charoenkwan, K.; Kietpeerakool, C. Retroperitoneal Drainage versus No Drainage after Pelvic Lymphadenectomy for the Prevention of Lymphocyst Formation in Women with Gynaecological Malignancies. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD007387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, K.; Zeng, L. A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis on Prophylactic Negative Pressure Wound Therapy versus Standard Dressing for Obese Women after Caesarean Section. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 5999–6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; Kim, N.K.; Kim, K.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, J.-M.; Lee, K.B.; Suh, D.H.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.K.; et al. Effects of Subcutaneous Drain on Wound Dehiscence and Infection in Gynecological Midline Laparotomy: Secondary Analysis of a Korean Gynecologic Oncology Group Study (KGOG 4001). Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 108484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardosi, R.J.; Drake, J.; Holmes, S.; Tebes, S.J.; Hoffman, M.S.; Fiorica, J.V.; Roberts, W.S.; Grendys, E.C. Subcutaneous management of vertical incisions with 3 or more centimeters of subcutaneous fat. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 195, 607Y614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panici, P.B.; Zullo, M.A.; Casalino, B.; Angioli, R.; Muzii, L. Subcutaneous drainage versus no drainage after minilaparotomy in gynecologic benign conditions: A randomized study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 188, 71Y75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.I.; Lim, M.C.; Bae, H.S.; Shin, S.R.; Seo, S.S.; Kang, S.; Park, S.Y. Benefit of negative pressure drain within surgical wound after cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer Off. J. Int. Gynecol. Cancer Soc. 2015, 25, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Nam, E.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, Y.T. Impact of subcutaneous negative pressure drains on surgical wound healing in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer Off. J. Int. Gynecol. Cancer Soc. 2021, 31, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.I.; Lim, M.C.; Song, Y.J.; Seo, S.S.; Kang, S.; Park, S.Y. Application of a subcutaneous negative pressure drain without subcutaneous suture: Impact on wound healing in gynecologic surgery. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014, 173, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Age-Period-Cohort Analysis of Hysterectomy Incidence Trends in Germany from 2005 to 2019|Scientific Reports. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-66019-8 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Čelebić, A.; Jakimovska Stefanovska, M.; Miladinović, M.; Calleja-Agius, J.; Starič, K.D. Evaluating the Role of Robotic Surgery in Gynecological Cancer Treatment. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 51, 109630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, R.; Forgione, A.; Akladios, C.; Querleu, D.; Mastrovito, S.; Pavone, M.; Marescaux, J.; Scambia, G. Is Vaginal Hysterectomy Outdated? A Systematic Overview of Reviews with Future Perspectives. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2025, 54, 102968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, I.; Samantaray, S.R. Unveiling the Uncommon: Vault Hematoma and Vault Cellulitis Following Hysterectomy—A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Przegląd Menopauzalny 2024, 23, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnaswamy, P.H.; Jha, S.; Krishnan, M. Efficiency of Using a Vaginal Drain after Hysterectomy: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 237, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.C.; Huang, F.J.; Hsu, T.Y.; Weng, H.H.; Chang, H.W.; Chang, S.Y. A prospective, randomized study of closed-suction drainage after laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 2002, 9, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Chon, S.J.; Lee, S.H.; Shin, J.W. Vaginal Vault Drainage as an Effective and Feasible Alternative in Laparoscopic Hysterectomy. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2022, 65, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.K.; Lucci, J.A.; Saja, P.J.; Manetta, A.; Berman, M.L. To drain or not to drain: A retrospective study of closed-suction drainage following radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy. Gynecol. Oncol. 1993, 51, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisomboon, J.; Phongnarisorn, C.; Suprasert, P.; Cheewakriangkrai, C.; Siriaree, S.; Charoenkwan, K. A Prospective Randomized Study Comparing Retroperitoneal Drainage with No Drainage and No Peritonization Following Radical Hysterectomy and Pelvic Lymphadenectomy for Invasive Cervical Cancer. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2002, 28, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, M.; Trimbos, J.B.; Zanaboni, F.; vd Velden, J.; Reed, N.; Coens, C.; Teodorovic, I.; Vergote, I. Randomised Trial of Drains versus No Drains Following Radical Hysterectomy and Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection: A European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Gynaecological Cancer Group (EORTC-GCG) Study in 234 Patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2007, 43, 1265–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patsner, B. Closed-Suction Drainage versus No Drainage Following Radical Abdominal Hysterectomy with Pelvic Lymphadenectomy for Stage IB Cervical Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 1995, 57, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bafna, U.D.; Umadevi, K.; Savitha, M. Closed Suction Drainage versus No Drainage Following Pelvic Lymphadenectomy for Gynecological Malignancies. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2001, 11, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morice, P.; Lassau, N.; Pautier, P.; Haie-Meder, C.; Lhomme, C.; Castaigne, D. Retroperitoneal Drainage after Complete Para-Aortic Lymphadenectomy for Gynecologic Cancer: A Randomized Trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 97, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.; Panici, P.B.; Guarglia, L.; Scambia, G.; Greggi, S.; Mancuso, S. Pelvic lymphocele following radical paraaortic and pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical carcinoma: Incidence rate and percutaneous management. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990, 76, 268–271. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, D.S.; Eisenhauer, E.L.; Zivanovic, O.; Sonoda, Y.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Levine, D.A.; Guile, M.W.; Bristow, R.E.; Aghajanian, C.; Barakat, R.R. Improved progression-free and overall survival in advanced ovarian cancer as a result of a change in surgical paradigm. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 114, 26Y31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourton, S.M.; Temple, L.K.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Gemignani, M.L.; Sonoda, Y.; Bochner, B.H.; Barakat, R.R.; Chi, D.S. Morbidity of rectosigmoid resection and primary anastomosis in patients undergoing primary cytoreductive surgery for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005, 99, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.L.; Mariani, A.; Cliby, W.A. Risk factors for anastomotic leak after recto-sigmoid resection for ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2006, 103, 667Y672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, K.; Omatsu, K.; Matoda, M.; Nomura, H.; Okamoto, S.; Kanao, H.; Utsugi, K.; Takeshima, N. Efficacy of Transanal Drainage Tube Placement After Modified Posterior Pelvic Exenteration for Primary Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2018, 28, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrowsky, H.; Demartines, N.; Rousson, V.; Clavien, P.A. Evidencebased value of prophylactic drainage in gastrointestinal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merad, F.; Yahchouchi, E.; Hay, J.M.; Fingerhut, A.; Laborde, Y.; Langlois-Zantain, O. Prophylactic abdominal drainage after elective colonic resection and suprapromontory anastomosis: A multicenter study controlled by randomization. Fr. Assoc. Surg. Res. Arch. Surg. 1998, 133, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Tsutsumi, S.; Fujii, T.; Morita, H.; Suto, T.; Nakajima, M.; Kato, H.; Asao, T.; Kuwano, H. Prophylactic and Informational Abdominal Drainage Is Not Necessary after Colectomy and Suprapromontory Anastomosis. Int. Surg. 2013, 98, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekavari, S.G.; Mahakalkar, C. Prophylactic Intra-Abdominal Drains in Major Elective Surgeries: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e54056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulou, C.; Planchamp, F.; Aytulu, T.; Chiva, L.; Cina, A.; Ergönül, Ö.; Fagotti, A.; Haidopoulos, D.; Hasenburg, A.; Hughes, C.; et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology Guidelines for the Peri-Operative Management of Advanced Ovarian Cancer Patients Undergoing Debulking Surgery. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oonk, M.H.M.; Planchamp, F.; Baldwin, P.; Mahner, S.; Mirza, M.R.; Fischerová, D.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Guillot, E.; Garganese, G.; Lax, S.; et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Vulvar Cancer—Update 2023. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 1023–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouwer, A.W.; Hinten, F.; van der Velden, J.; Smolders, R.G.; Slangen, B.F.; Zijlmans, H.J.M.A.A.; IntHout, J.; van der Zee, A.G.; Boll, D.; Gaarenstroom, K.N.; et al. Volume-Controlled versus Short Drainage after Inguinofemoral Lymphadenectomy in Vulvar Cancer Patients: A Dutch Nationwide Prospective Study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 146, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, N.; Kamelle, S.; Tillmanns, T.; Scribner, D.; Gold, M.; Walker, J.; Mannel, R. Predictors of Complications after Inguinal Lymphadenectomy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2001, 82, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.F.; Day, H.; Abu, J.; Nunns, D.; Williamson, K.; Duncan, T. Do Surgical Techniques Used in Groin Lymphadenectomy for Vulval Cancer Affect Morbidity Rates? Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2011, 21, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontre, J.; Harding, J.; Chivers, P.; Loughlin, L.; Leung, Y.; Salfinger, S.G.; Tan, J.; Mohan, G.R.; Cohen, P.A. Do Groin Drains Reduce Postoperative Morbidity in Women Undergoing Inguinofemoral Lymphadenectomy for Vulvar Cancer? Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2018, 28, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACOG Committee Opinion. No. 750: Perioperative Pathways: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, e120–e130, Correction in: Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, G.; Bakkum-Gamez, J.; Kalogera, E.; Glaser, G.; Altman, A.; Meyer, L.A.; Taylor, J.S.; Iniesta, M.; Lasala, J.; Mena, G.; et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Gynecologic/Oncology: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations-2019 Update. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2019, 29, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandoria, G.P.; Bhandarkar, P.; Ahuja, V.; Maheshwari, A.; Sekhon, R.K.; Gultekin, M.; Ayhan, A.; Demirkiran, F.; Kahramanoglu, I.; Wan, Y.-L.L.; et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) in Gynecologic Oncology: An International Survey of Peri-Operative Practice. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 1471–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Hidalgo, N.R.; Pletnev, A.; Razumova, Z.; Bizzarri, N.; Selcuk, I.; Theofanakis, C.; Zalewski, K.; Nikolova, T.; Lanner, M.; Kacperczyk-Bartnik, J.; et al. European Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Gynecologic Oncology Survey: Status of ERAS Protocol Implementation across Europe. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2023, 160, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Studies | Type of Study | Patients | Type of Operation | Type of Drain | Febrile Morbidity Rates (Drain vs. No Drain) | Mean Length of Hospital Stay in Days (Drain vs. No Drain) | Lymphocysts Formation (Drain vs. No Drain) | Post-Operative Complications (Drain vs. No Drain) | Conclusions Regarding the Prophylactic Drainage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jensen et al. [21] | Retrospective cohort | Early-stage cervical cancer | 1 RHPL | Jackson–Pratt closed-suction drainage | 32.8% vs. 29.1% (2 NS) | 7.6 ± 2.4 vs. 7.0 ± 1.3 (2 NS) | - | - | Possibly unnecessary with post-operative complication risk |

| Srisomboon et al. [22] | Prospective randomized | Early-stage cervical cancer | 1 RHPL | Retroperitoneal low-pressure closed-suction drains | 5.8% vs. 0% (2 NS) | 9.4 ± 1.6 vs. 9.2 ± 1.4 (2 NS) | 2 NS, p = 0.2 | - | Can safely be omitted |

| Franchi et al. [23] | Prospective randomized | Early-stage cervical cancer | 1 RHPL | Passive or active suction drains | - | - | 5.9% vs. 0.9% (2 NS, p = 0.06) | 0.53% vs. 0.66% (2 NS) | Can safely be omitted in minimal intra-operative bleeding |

| Patsner et al. [24] | Prospective non-randomized study | Early-stage cervical cancer | 1 RHPL | Jackson–Pratt closed-suction drainage | 10% vs. 3.3% (2 NS) | 5.5 vs. 4.5 (2 NS) | 11.6% vs. 0% (2 NS) | - | Can safely be omitted |

| Bafna et al. [25] | Prospective non-randomized | Various gynecologic malignancies | Pelvic ± aortocaval 3 LND | Closed-suction retroperitoneal pelvic drainage | - | 10 vs. 10 (2 NS) | 7.2% vs. 2.7% (2 NS, p > 0.05) | - | No benefit over open peritoneum without drainage |

| Morice et al. [26] | Randomized trial | Ovarian or cervical carcinoma | Complete para-aortic 3 LND up to the level of the left renal vein | Pelvic suction drains (Bellovac; Astratech) | - | 11 vs. 9 (p < 0.03) | 5% vs. 24% (p < 0.05) | 36% vs. 13% (p < 0.02) | Should be abandoned due to increased morbidity and hospitalization duration |

| Charoenkwan et al. [6] | Systematic review | Various gynecologic malignancies | Systematic pelvic or pelvic and aortic 3 LND | Passive or active suction retroperitoneal drains | - | - | 2 NS | - | No benefit preventing lymphocyst formation |

| International Guidelines | Upper Abdominal Complications | Diaphragmatic Surgery | Pleural Effusion | Post-Op Collections or Abscess | Diet | Urinary Catheter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESGO guidelines [36] | Could be considered in large-volume ascites and extensive peritoneal and/or lymph node resections (III, C) | Not routinely indicated (III, B) | Could be considered in cases of high-volume pre-operative pleura effusion, frailty, hypoalbuminemia, and large diaphragmatic resection (III, B) | Preferable management: Image-guided percutaneous drainage (III, B) | - | - |

| ACOG committee opinion and ERAS protocol [42] | Avoidance of drains and vaginal packs | -No nasogastric tube -Regular diet and gum chewing 4 h post-operatively | Removal within 24 h | |||

| ERAS Society recommendations—2019 update [43] | Avoidance of drains/tubes | Post-operatively for a short period; preferably <24 h post-op | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Margioula-Siarkou, C.; Almperis, A.; Almperi, E.-A.; Margioula-Siarkou, G.; Flindris, S.; Daponte, N.; Daponte, A.; Dinas, K.; Petousis, S. Prophylactic and Therapeutic Usage of Drains in Gynecologic Oncology Procedures: A Comprehensive Review. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15060254

Margioula-Siarkou C, Almperis A, Almperi E-A, Margioula-Siarkou G, Flindris S, Daponte N, Daponte A, Dinas K, Petousis S. Prophylactic and Therapeutic Usage of Drains in Gynecologic Oncology Procedures: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(6):254. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15060254

Chicago/Turabian StyleMargioula-Siarkou, Chrysoula, Aristarchos Almperis, Emmanouela-Aliki Almperi, Georgia Margioula-Siarkou, Stefanos Flindris, Nikoletta Daponte, Alexandros Daponte, Konstantinos Dinas, and Stamatios Petousis. 2025. "Prophylactic and Therapeutic Usage of Drains in Gynecologic Oncology Procedures: A Comprehensive Review" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 6: 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15060254

APA StyleMargioula-Siarkou, C., Almperis, A., Almperi, E.-A., Margioula-Siarkou, G., Flindris, S., Daponte, N., Daponte, A., Dinas, K., & Petousis, S. (2025). Prophylactic and Therapeutic Usage of Drains in Gynecologic Oncology Procedures: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(6), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15060254