Non-Communicable Disease (NCD) Management During Disasters and Humanitarian Emergencies: A Review of the Experiences Reported by Emergency Medical Teams (EMTs)

Abstract

1. Introduction

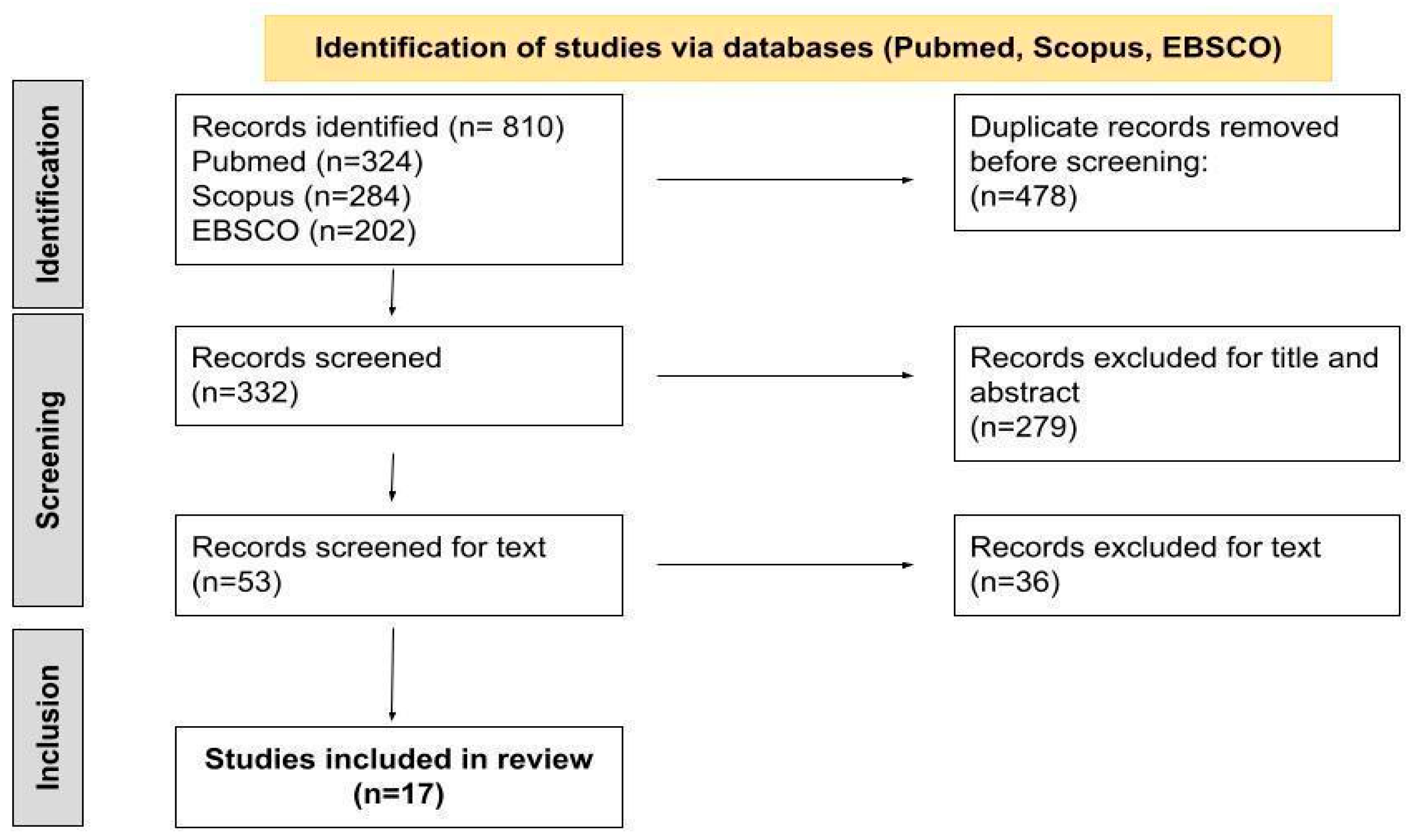

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

| Studies Included | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Author | Year of Publication | Title | Methodology | Aim | Disaster Setting | Disaster Time of Occurrence |

| Fernald [30] | 2007 | The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital Humanitarian Assistance Mission in Pakistan: The Primary Care Experience | Cross-sectional study | To describe the experiences during the deployment of a mobile army surgical hospital | Pakistan earthquake | 8 October 2005 |

| Guha-Sapir [31] | 2007 | Patterns of chronic and acute diseases after natural disasters—a study from the International Committee of the Red Cross field hospital in Banda Aceh after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami | Cross-sectional, record-based study | To assess the pattern of diseases in the immediate aftermath of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami | Indian Ocean tsunami | December 2004 |

| Hung [29] | 2013 | Disease pattern and chronic illness in rural China: the Hong Kong Red Cross basic health clinic after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake | Cross-sectional records-based study | To identify the health needs and chronic disease prevalence of rural Chinese following a major earthquake | Sichuan earthquake, China | 12 May 2008 |

| van Berlaer [28] | 2016 | A refugee camp in the center of Europe: clinical characteristics of asylum seekers arriving in Brussels | Descriptive cross-sectional study design | To describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of asylum seekers who arrived in a huddled refugee camp in Brussels | Syrian civil war and Syrian exodus | Summer 2015 |

| McDermott [27] | 2017 | Management of Diabetic Surgical Patients in a Deployed Field Hospital: A Model for Acute Non-Communicable Disease Care in Disaster | Descriptive analysis | To improve the care of diabetic patients in humanitarian settings by exploring a case study of NCD management in a surgical field hospital | Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda), Philippines | 8 November 2013 |

| Dunne-Sosa [25] | 2019 | The Hidden Wounds of Hurricane Dorian | Field Report | To report the mission of the HOPE Emergency Response Team | Hurricane Dorian, Bahamas | 1 September 2019 |

| van Berlaer [26] | 2019 | Clinical Characteristics of the 2013 Haiyan Typhoon Victims Presenting to the Belgian First Aid and Support Team | Cross-sectional study | To document the demographics, complaints, comorbidities, diagnoses, diagnosis categories, and management of typhoon victims who sought medical assistance in a field hospital of an international EMT, and to formulate recommendations for future relief operations | Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda), Philippines | 8 November 2013 |

| Bartolucci [23] | 2021 | Decision Support Framework for Deployment of Emergency Medical Teams After Earthquakes | Desk-based study | To enhance disaster managers’ literacy and to provide a framework that will assist those responsible for deploying and/or accepting EMTs in making informed decisions on the deployment of emergency medical teams after an earthquake | Earthquakes | Not specified |

| McMaster [24] | 2020 | Integrating specialist ophthalmic services into emergency medical teams | Discussion paper | To describe the importance of increasing specialist ophthalmic services within emergency medical teams | Conflicts (not specified), Earthquakes, infectious disease outbreaks | Conflicts (Timor-Leste and others not specified), Earthquakes (Japan in 2011 and Nepal in 2015), Ebola (West Africa, 2013–16) and measles outbreaks (Pacific region, 2019) |

| Ladeira [21] | 2021 | PT EMT—Portuguese Emergency Medical Team Type 1 Relief Mission in Mozambique | Descriptive analysis | To report the mission of the PT EMT type 1 in Mozambique | Cyclone Idai | 15 March 2019 |

| Dulacha [16] | 2022 | Use of mobile medical teams to fill critical gaps in health service delivery in complex humanitarian settings, 2017–2020: a case study of South Sudan | Descriptive analysis | To analyze the key achievements of emergency mobile medical teams (eMMT) in disaster settings of South Sudan | Conflicts, floods, famine, and disease outbreaks in South Sudan | 2017–2020 |

| McMaster [20] | 2022 | Designing a Mobile Eye Hospital to Support Health Systems in Resource-Scarce Environments | Discussion paper | To propose a design plan for a mobile eye hospital to support health systems between the initial emergency response and recovery of health infrastructure in resource-scarce environments of low- and middle-income countries. | Not specified | Not specified |

| Foo [32] | 2022 | Establishment of disaster medical assistance team standards and evaluation of the teams’ disaster preparedness: An experience from Taiwan | Delphi study (Phase 1)/Cross-sectional study (Phase 2) | To develop localized Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (DMATs) standards for Taiwan by referring to EMT type I standards, and to further evaluate the disaster preparedness of Taiwan’s DMAT | Chi-Chi earthquake | September 2019 |

| Chimed Ochir [19] | 2022 | Emergency Medical Teams’ Responses during the West Japan Heavy Rain 2018: J-SPEED Data Analysis | Descriptive epidemiology study | To better understand the health problems during floods and heavy rain disasters | West Japan Heavy Rain | 8 July–11 September 2018 |

| Sacchetto [18] | 2022 | Italian Field Hospital Experience in Mozambique: Report of Ordinary Activities in an Extraordinary Context | Descriptive analysis | To report the mission of the EMT2-ITA in Mozambique, raising interesting points of discussion regarding the impact of timing on the mission outcomes, the operational and clinical activities in the field hospital, and the great importance to integrate local staff into the team | Cyclone Idai, Mozambique | 15 March 2019 |

| Tachikawa [22] | 2022 | Mental health needs associated with COVID-19 on the diamond princess cruise ship: A case series recorded by the disaster psychiatric assistance team | Descriptive analysis | To assess the clinical characteristics of patients with acute mental health needs on the quarantined ship Diamond Princess and recommend evidence-based measures for disaster mitigation | COVID-19 Pandemic, Japan | 9–21 February 2020 |

| Yumiya [17] | 2022 | Prevalence of Mental Health Problems among Patients Treated by Emergency Medical Teams: Findings from J-SPEED data regarding the West Japan Heavy Rain 2018 | Descriptive analysis | To examine how mental health needs are accounted for in the overall picture of disaster relief, and how they change overtime | West Japan Heavy Rain | 8 July–11 September 2018 |

| Emergency Medical Teams (EMTs) and Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) Management | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Author/ Year of Publication | EMTs Type | EMTs Clinical Staff | EMTs Equipment (Related to NCDs) | NCDs Registered | Challenges Reported (Related to NCD Treatment) |

| Dulacha/2022 [16] | Type 1 mobile | Epidemiologists, clinicians or doctors, nurses, laboratory specialists, nutritionists, health promotion experts, and public health officers | Emergency health kits Laboratory sample collection kits | Chronic conditions not specified | Absence of strategies to ensure the continued provision of services for the chronic conditions initially managed during the mobile outreach |

| McMaster/2022 [20] | EMT Specialized in eye diseases (a mobile eye hospital) | Ophthalmologists, ophthalmic assistants, nurses, and anesthesiologists | Examination equipment with visual acuity charts, a portable slit lamp, indirect ophthalmoscope, tonometer, fundus lenses, compact A/B ultrasound scanner, autorefractor, sphygmomanometer, and expendable supplies such as eye drops and reagents for estimating urine sugar concentration | Chronic eye diseases (including diseases caused by NCDs) | Not specified |

| Chimed Ochir/2022 [19] | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Cardiovascular diseases, disaster stress-related symptoms | Not specified |

| Sacchetto/2022 [18] | Type 2 | 58 healthcare professionals (29 medical doctors, including two team leaders and one deputy team leader; 27 nurses; one x-ray technician; and one midwife) | Not specified | Cardiovascular, neurologic, and respiratory diseases | Only a few patients with specific disaster-related injuries: → many patients come to the field hospital for routine medical care |

| Yumiya/2022 [17] | Type 1 and 2 | Not specified | Not specified | Mental health problems and disaster stress-related symptoms | Not specified |

| Tachikawa/2022 [22] | Disaster Psychiatric Assistance Team (DPAT) | Fifty-five members of 12 DPAT groups | Psychological advice and Psychiatric assistance | Mental health disorders | Not specified |

| Ladeira/2021 [21] | Type 1 mobile | Two-team rotation (28 elements each). Doctors of different specialties (i.e., intensive care, internal medicine, pediatrics, surgery, obstetrics, and infectious diseases); specialized nurses in critically ill patients, or emergency and disaster; prehospital technicians; psychologists; x-ray technicians; pharmaceuticals | X-Ray, in addition to the standard equipment | Low back pain, headache, and gastritis | The World Health Organization Minimal Data Set register is insufficient to allow an adequate classification of all the NCDs managed during the EMT deployment |

| Foo/2021 [32] | DMAT (Disaster Medical Assistance Teams) type 1 fixed | 1:2:2 ratio of physicians:nurses:logisticians | Ultrasound services have been added to the standard services | Emergency chronic disease care | Not reported |

| Bartolucci/2020 [23] | Type 1, 2, and 3 | Not specified | Not specified | Chronic health conditions | Difficulties in standardizing the EMTs’ time of deployment Unpredictability of disasters, logistical complications, and local protocols and procedures that can affect the EMTs’ registration and location assignments |

| McMaster/2020 [24] | Type 1, 2, and 3 | Specialist ophthalmology units capable of integrating into type 1, 2, and 3 EMTs | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| van Berlaer/2019 [26] | Belgian First Aid and Support Team (B-FAST) | Volunteer team comprising 5 physicians (1 surgeon, 3 anesthesiologists trained in emergency medicine, and 1 pediatrician); 15 skilled nurses | Preconfigured interagency emergency health kits (IEHKs) | Diabetes, hypertension, asthma, and mental health disorders | The widely used basic IEHK, does not contain sufficient medication refills for patients, so B-FAST provided, by their own means, refills of medication and distribution of materials like beta-blockers, inhalers, and urine ketone strips Follow-up or referral of patients |

| Dunne Sosa/2019 [25] | HOPE Emergency Response Team | Medical volunteers | Insulin needles, hygiene kits | Chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and cancer | Not specified |

| McDermott/2017 [27] | Type 2 | Two consecutive acute trauma surgery teams, 1 internal medicine physician per team, 1 pharmacist per team, no nursing staff with a primary specialty of patient inward | Blood glucose monitoring, dipstick Urinalysis, fast-acting insulin, metformin | Diabetes | Local medical supplies depleted quickly: →people with diabetes found that they had no medication and limited means of obtaining renewed supply The medication available was limited →normal regimes were not available →people had to change to unfamiliar drugs Prescriptions were not necessarily available along with medical records →reliance was made on diabetic patients memorizing their regular medications |

| Van Berlaer/2016 [28] | Field Hospital (Médecins du monde, MdM) | 400 certified physicians, nurses, pharmacists, logisticians, and interpreters. MdM registered all volunteers and verified their diplomas and license to work in Belgium. An outpatient assistance team with a physician, a nurse, and an interpreter provided on-the-spot healthcare for patients not able to leave their tents, or referred them to the field hospital for further care when necessary | Not reported | Respiratory diseases, skin, digestive diseases, hypertension, diabetes, asthma, epilepsy, mental health issues | Not reported |

| Hung/2013 [29] | Hong Kong Red Cross (HKRC) basic healthcare clinic | HKRC medical teams are composed of seven doctors, six nurses, and one senior health coordinator, all providing basic healthcare to villagers | Not reported | Musculoskeletal, respiratory, gastrointestinal problems, and a high prevalence of hypertension | Management of chronic diseases was an important issue |

| Guha-Sapir/2007 [31] | Red Cross field hospital | Not reported | Not reported | Respiratory diseases, hypertension, diabetes, and acute manifestation of chronic diseases (e.g., asthma), mental diseases, chronic musculoskeletal disease, headache, gastroesophageal reflux, cerebrovascular accidents, renal failure, myocardial infarction | |

| Fernald/2007 [30] | Mobile Army Surgical hospital (MASH) | Surgery team implemented with two family medicine physicians, one pediatrician, and one internist | Not reported | Chronic musculoskeletal disease, headache, gastroesophageal reflux, cerebrovascular accidents, renal failure, myocardial infarction, respiratory failure | After the first month of the mission, the surgical patient load decreased, whereas primary care increased to 90% of patient encounters →delay in establishing a clear, concise plan for primary care |

| Non Communicable Diseases (NCDs) Mana | |

|---|---|

| Emergency Medical Teams (EMTs) | Suggestions |

| Pre-departure preparation | Ensure that patients with chronic conditions are monitored and their medication is maintained during the disaster [21] |

| Stockpile disaster-response equipment and drugs in strategic areas in disaster-prone regions to guarantee that proper EMT equipment is promptly available [28] | |

| Align with the national pharmaceutical formulary of the disaster-affected host nation to guarantee proper EMT equipment and an adequate pharmacological load [29] | |

| Define clear operational guidelines on NCDs field management and on patients’ follow-up [29] | |

| Medical responders need to be aware of the potential pre-existing disease burden in the community, with the possible exacerbation in post-disaster situations [31] | |

| Operational time and length of stay | Become operative two or more weeks after a disaster requires being more prompt in ensuring elective activities aimed at maintaining the ordinary healthcare capacity of the affected country [20] |

| Follow a recovery approach based on different time periods in order to guarantee assistance for health needs that arise at different times in disasters aftermath [19] | |

| Provide a semi-permanent service between the initial emergency response and the re-establishment of local health services delivery [22] | |

| Ensure a continuous services provision system for patients when an EMT exit strategy is planned [19] | |

| Ensuring continuity of care for longer than the initial two weeks after the disaster onset [27] | |

| Staff composition and training | Include internal medicine specialists and nurses familiar with inpatient management of chronic diseases to be deployed in chronic condition management, such as diabetes [29] |

| Including family medicine physicians and internists to ensure primary care for the affected population [32] | |

| Train staff to be deployed in chronic conditions management, mental health disorders, and psychosocial problems management [18,19] | |

| Deployed health professionals should be trained in specific conditions management, such as ocular diseases [26] | |

| Medical teams should be prepared for acute presentations of chronic illnesses [33] | |

| Psychiatric care should be anticipated for both disaster-related and pre-disaster patients [33] | |

| Compassion fatigue and staff burnout must be anticipated. In prolonged missions, 1 day of rest per week for staff members is essential. Translators are especially vulnerable to mental fatigue [32] | |

| EMTs addressing mental health issues are essential services for the maintenance of public health during crisis situations [24] | |

| Equipment | Enhance medication inventories to include a range of common drugs for chronic diseases and stock pharmacies adequately [27,29,32] |

| Consider the addition of X-Ray (EMTs type 1) in the standard equipment to improve the diagnosis capacity [23] | |

| Consider the addition of ultrasound (EMTs type 1) in the standard equipment to improve the diagnosis capacity [34] | |

| Consider the addition of analgesic drugs in the standard equipment to better address the needs of vulnerable populations [23] | |

| The cold chain system is a necessary and basic requirement to store medications such as insulin [27,34] | |

| Integration with local health staff | Working in integration and not in overlap with local health services [16,18,20,23] |

| The collaboration with community health workers, community-based organizations, local health facilities, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) is a key element to ensure the continuous treatment of patients with chronic illnesses [16,18,29,31] | |

| The collaboration with local health staff is a key element to promote the health education of the local population, including education on emergency preparedness [27,28] | |

| The collaboration with local health staff is a key element to guarantee the sustainability of EMT interventions [18] | |

| The integration of the local staff in the team composition during the rotation of the personnel allowed, on one side, to limit the number of professionals coming from the EMTs’ country of origin and, on the other side, to ensure an effective training of local health workers [20] | |

| EMTs can work synergistically to achieve better outcomes [34] | |

| Data collection and reporting system | An adequate data collection system is crucial to report EMTs’ clinical activities, in order to avoid underestimation of chronic health conditions [21] |

| An adequate data collection system is crucial to facilitate the reintegration of patients into the local health system [29] | |

| The implementation of digital health services allows EMTs to capture the relevant data from the catchment populations where they are conducting their outreach [23] | |

| A more precise identification of NCDs in the WHO EMTs Minimum Data Set (MDS) should be considered, in order to guarantee a more precise identification of EMTs’ clinical activities [23] | |

| Other | The government should formulate a system to provide EMT members with adequate insurance when deployed (they work under safety and security threats) [34] |

| EMTs should receive adequate financial support (2021) [34] | |

| EMTs should educate patients with chronic illnesses on emergency preparedness [34] | |

3.1. NCDs Management

3.1.1. NCDs Reported

3.1.2. Challenges Faced

3.1.3. Actions Taken

3.2. EMTs Characteristics

3.2.1. Type

3.2.2. Staff Composition

3.2.3. Operational Time, Length of Stay, and Opening Hours

3.2.4. Equipment

3.2.5. Data Collection

3.2.6. Patients’ Referral

3.3. Recommendations to Improve EMT-Related Management of NCDs

3.3.1. Pre-Departure Preparation, Time of Deployment, and Length of Stay

3.3.2. Staff Composition and Training

3.3.3. Equipment

3.3.4. Integration and Coordination

3.3.5. Data Collection and Reporting System

3.3.6. Other Recommendations

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction (2009)|UNDRR. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/global-assessment-report-disaster-risk-reduction-2009 (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Emergency Medical Teams. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/partners/emergency-medical-teams (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- WHO-PAHO Guidelines for the Use of Foreign Field Hospitals in the Aftermath of Sudden-Impact Disasters—PAHO/WHO|Pan American Health Organization. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/response-haitis-earthquake-2010 (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Brandrud, A.S.; Bretthauer, M.; Brattebø, G.; Pedersen, M.J.; Håpnes, K.; Møller, K.; Bjorge, T.; Nyen, B.; Strauman, L.; Schreiner, A.; et al. Local Emergency Medical Response after a Terrorist Attack in Norway: A Qualitative Study. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017, 26, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, K.R.; Nagel, N.E. Mass Medical Evacuation: Hurricane Katrina and Nursing Experiences at the New Orleans Airport. Disaster Manag. Response DMR Off. Publ. Emerg. Nurses Assoc. 2007, 5, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, M.; Counahan, M.; Hall, J.L. Responding to Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. West. Pac. Surveill. Response J. WPSAR 2015, 6 (Suppl. S1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazanchaei, E.; Mohebbi, I.; Nouri, F.; Aghazadeh-Attari, J.; Khorasani-Zavareh, D. Non-Communicable Diseases in Disasters: A Protocol for a Systematic Review. J. Inj. Violence Res. 2021, 13, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runkle, J.D.; Brock-Martin, A.; Karmaus, W.; Svendsen, E.R. Secondary Surge Capacity: A Framework for Understanding Long-Term Access to Primary Care for Medically Vulnerable Populations in Disaster Recovery. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, e24–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-khani, U.; Ashrafian, H.; Rasheed, S.; Veen, H.; Darwish, A.; Nott, D.; Darzi, A. The Patient Safety Practices of Emergency Medical Teams in Disaster Zones: A Systematic Analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, F.J.; Beran, D.; Hering, H.; Boulle, P.; Chappuis, F.; Dromer, C.; Saaristo, P.; Perone, S.A. Operational Considerations for the Management of Non-Communicable Diseases in Humanitarian Emergencies. Confl. Health 2021, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoping Reviews—JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis—JBI Global Wiki. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355862497/10.+Scoping+reviews (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, M.; Wiebe, N.; Nadler, B.; Darzi, A.; Rasheed, S. Modifying the Interagency Emergency Health Kit to Include Treatment for Non-Communicable Diseases in Natural Disasters and Complex Emergencies. BMJ Glob. Health 2016, 1, e000128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Package of Essential Noncommunicable (PEN) Disease Interventions for Primary Health Care. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240009226 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Non Communicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Dulacha, D.; Ramadan, O.P.C.; Guyo, A.G.; Maleghemi, S.; Wamala, J.F.; Gimba, W.G.W.; Wurda, T.T.; Odra, W.; Yur, C.T.; Loro, F.B.; et al. Use of Mobile Medical Teams to Fill Critical Gaps in Health Service Delivery in Complex Humanitarian Settings, 2017–2020: A Case Study of South Sudan. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 42, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumiya, Y.; Chimed-Ochir, O.; Taji, A.; Kishita, E.; Akahoshi, K.; Kondo, H.; Wakai, A.; Chishima, K.; Toyokuni, Y.; Koido, Y.; et al. Prevalence of Mental Health Problems among Patients Treated by Emergency Medical Teams: Findings from J-SPEED Data Regarding the West Japan Heavy Rain 2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 11454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacchetto, D.; Raviolo, M.; Lovesio, S.; Salio, F.; Hubloue, I.; Ragazzoni, L. Italian Field Hospital Experience in Mozambique: Report of Ordinary Activities in an Extraordinary Context. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2022, 37, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimed-Ochir, O.; Yumiya, Y.; Taji, A.; Kishita, E.; Kondo, H.; Wakai, A.; Akahoshi, K.; Chishima, K.; Toyokuni, Y.; Koido, Y.; et al. Emergency Medical Teams’ Responses during the West Japan Heavy Rain 2018: J-SPEED Data Analysis. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2022, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMaster, D.; Clare, G. Designing a Mobile Eye Hospital to Support Health Systems in Resource-Scarce Environments. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 1618–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladeira, L.M.; Cardoso, I.; Ribeiro, H.; Lourenço, J.; Ramos, R.; Barros, F.; Rato, F. PT EMT—Portuguese Emergency Medical Team Type 1 Relief Mission in Mozambique. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2021, 36, 651–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachikawa, H.; Kubo, T.; Gomei, S.; Takahashi, S.; Kawashima, Y.; Manaka, K.; Mori, A.; Kondo, H.; Koido, Y.; Ishikawa, H.; et al. Mental Health Needs Associated with COVID-19 on the Diamond Princess Cruise Ship: A Case Series Recorded by the Disaster Psychiatric Assistance Team. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. IJDRR 2022, 81, 103250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolucci, A.; Mackway-Jones, K.; Redmond, A.D. Decision Support Framework for Deployment of Emergency Medical Teams After Earthquakes. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 15, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMaster, D.; Clare, G. Integrating Specialist Ophthalmic Services into Emergency Medical Teams. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 722–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne-Sosa, A.; Cotter, T. The Hidden Wounds of Hurricane Dorian: Why Emergency Response Must Look Beyond Physical Trauma. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 13, 1092–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Berlaer, G.; de Jong, F.; Das, T.; Gundran, C.P.; Samyn, M.; Gijs, G.; Buyl, R.; Debacker, M.; Hubloue, I. Clinical Characteristics of the 2013 Haiyan Typhoon Victims Presenting to the Belgian First Aid and Support Team. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 13, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, K.M.; Hardstaff, R.M.; Alpen, S.; Read, D.J.; Coatsworth, N.R. Management of Diabetic Surgical Patients in a Deployed Field Hospital: A Model for Acute Non-Communicable Disease Care in Disaster. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2017, 32, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Berlaer, G.; Bohle Carbonell, F.; Manantsoa, S.; de Béthune, X.; Buyl, R.; Debacker, M.; Hubloue, I. A Refugee Camp in the Centre of Europe: Clinical Characteristics of Asylum Seekers Arriving in Brussels. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e013963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, K.K.C.; Lam, E.C.C.; Chan, E.Y.Y.; Graham, C.A. Disease Pattern and Chronic Illness in Rural China: The Hong Kong Red Cross Basic Health Clinic after 2008 Sichuan Earthquake. Emerg. Med. Australas. EMA 2013, 25, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernald, J.P.; Clawson, E.A. The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital Humanitarian Assistance Mission in Pakistan: The Primary Care Experience. Mil. Med. 2007, 172, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guha-Sapir, D.; van Panhuis, W.G.; Lagoutte, J. Short Communication: Patterns of Chronic and Acute Diseases after Natural Disasters—A Study from the International Committee of the Red Cross Field Hospital in Banda Aceh after the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. Trop. Med. Int. Health TM IH 2007, 12, 1338–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, N.-P.; Cheng, Y.-Y.; Hung, Y.-C.; Pan, S.-T.; Chen, Y.-L.; Hu, K.-W.; Chen, C.-Y. Establishment of Disaster Medical Assistance Team Standards and Evaluation of the Teams’ Disaster Preparedness: An Experience from Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. Taiwan Yi Zhi 2022, 121, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngaruiya, C.; Bernstein, R.; Leff, R.; Wallace, L.; Agrawal, P.; Selvam, A.; Hersey, D.; Hayward, A. Systematic Review on Chronic Non-Communicable Disease in Disaster Settings. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, R.; Selvam, A.; Bernstein, R.; Wallace, L.; Hayward, A.; Agrawal, P.; Hersey, D.; Ngaruiya, C. A Review of Interventions for Noncommunicable Diseases in Humanitarian Emergencies in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Am. J. Disaster Med. 2022, 16, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inclusion of Noncommunicable Disease Care in Response to Humanitarian Emergencies Will Help Save More Lives. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/news/press-releases/inclusion-noncommunicable-disease-care-response-humanitarian-emergencies-will (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Integrating Non-Communicable Disease Care in Humanitarian Settings, 2020 (PDF). Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/media/integrating-non-communicable-disease-care-humanitarian-settings-2020-pdf (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Parati, G.; Antonicelli, R.; Guazzarotti, F.; Paciaroni, E.; Mancia, G. Cardiovascular Effects of an Earthquake: Direct Evidence by Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring. Hypertens. Dallas Tex 1979 2001, 38, 1093–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, M.; Kawashiri, M.-A.; Teramoto, R.; Takata, M.; Sakata, K.; Omi, W.; Okajima, M.; Takamura, M.; Ino, H.; Kita, Y.; et al. Impact of Severe Earthquake on the Occurrence of Acute Coronary Syndrome and Stroke in a Rural Area of Japan. Circ. J. Off. J. Jpn. Circ. Soc. 2009, 73, 1243–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, S.H.; Farinaro, E.; Krogh, V.; Jossa, F.; Scottoni, A.; Trevisan, M. Long Term Relations between Earthquake Experiences and Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factors. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 151, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Lin, J.; Luo, X.; Luo, X. Acute Changes of Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Induced by a Strong Earthquake. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2010, 123, 1084–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Kloner, R.A.; Leor, J.; Poole, W.K.; Perritt, R. Population-Based Analysis of the Effect of the Northridge Earthquake on Cardiac Death in Los Angeles County, California. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1997, 30, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Y.; Wu, C.C.; Liu, Y.B.; Ho, Y.L.; Liau, C.S.; Lee, Y.T. Derangement of Heart Rate Variability during a Catastrophic Earthquake: A Possible Mechanism for Increased Heart Attacks. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. PACE 2001, 24, 1596–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parotto, E.; Isidoris, V.; Cavestro, A.; Atzori, A. Health Needs of Ukrainian Refugees Displaced in Moldova: A Report from an Italian Emergency Medical Team. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2025, 40, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Oraibi, A.; Hassan, O.; Chattopadhyay, K.; Nellums, L.B. The Prevalence of Non-Communicable Diseases among Syrian Refugees in Syria’s Neighbouring Host Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Public Health 2022, 205, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interagency Emergency Health Kit 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/emergency-health-kits/interagency-emergency-health-kit-2017 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Shalash, A.; Abu-Rmeileh, N.M.E.; Kelly, D.; Elmusharaf, K. The Need for Standardised Methods of Data Collection, Sharing of Data and Agency Coordination in Humanitarian Settings. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e007249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parotto, E.; Lamberti-Castronuovo, A.; Censi, V.; Valente, M.; Atzori, A.; Ragazzoni, L. Exploring Italian Healthcare Facilities Response to COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Learned from the Italian Response to COVID-19 Initiative. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1016649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayarifard, A.; Nazari, M.; Rajabi, F.; Ghadirian, L.; Sajadi, H.S. Identifying the Non-Governmental Organizations’ Activities and Challenges in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Iran. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parotto, E.; Salio, F.; Valente, M.; Ragazzoni, L. Non-Communicable Disease (NCD) Management During Disasters and Humanitarian Emergencies: A Review of the Experiences Reported by Emergency Medical Teams (EMTs). J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15060255

Parotto E, Salio F, Valente M, Ragazzoni L. Non-Communicable Disease (NCD) Management During Disasters and Humanitarian Emergencies: A Review of the Experiences Reported by Emergency Medical Teams (EMTs). Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(6):255. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15060255

Chicago/Turabian StyleParotto, Emanuela, Flavio Salio, Martina Valente, and Luca Ragazzoni. 2025. "Non-Communicable Disease (NCD) Management During Disasters and Humanitarian Emergencies: A Review of the Experiences Reported by Emergency Medical Teams (EMTs)" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 6: 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15060255

APA StyleParotto, E., Salio, F., Valente, M., & Ragazzoni, L. (2025). Non-Communicable Disease (NCD) Management During Disasters and Humanitarian Emergencies: A Review of the Experiences Reported by Emergency Medical Teams (EMTs). Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(6), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15060255