Enhancing Traumatic Stress Recovery Through Nonattachment Principles: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

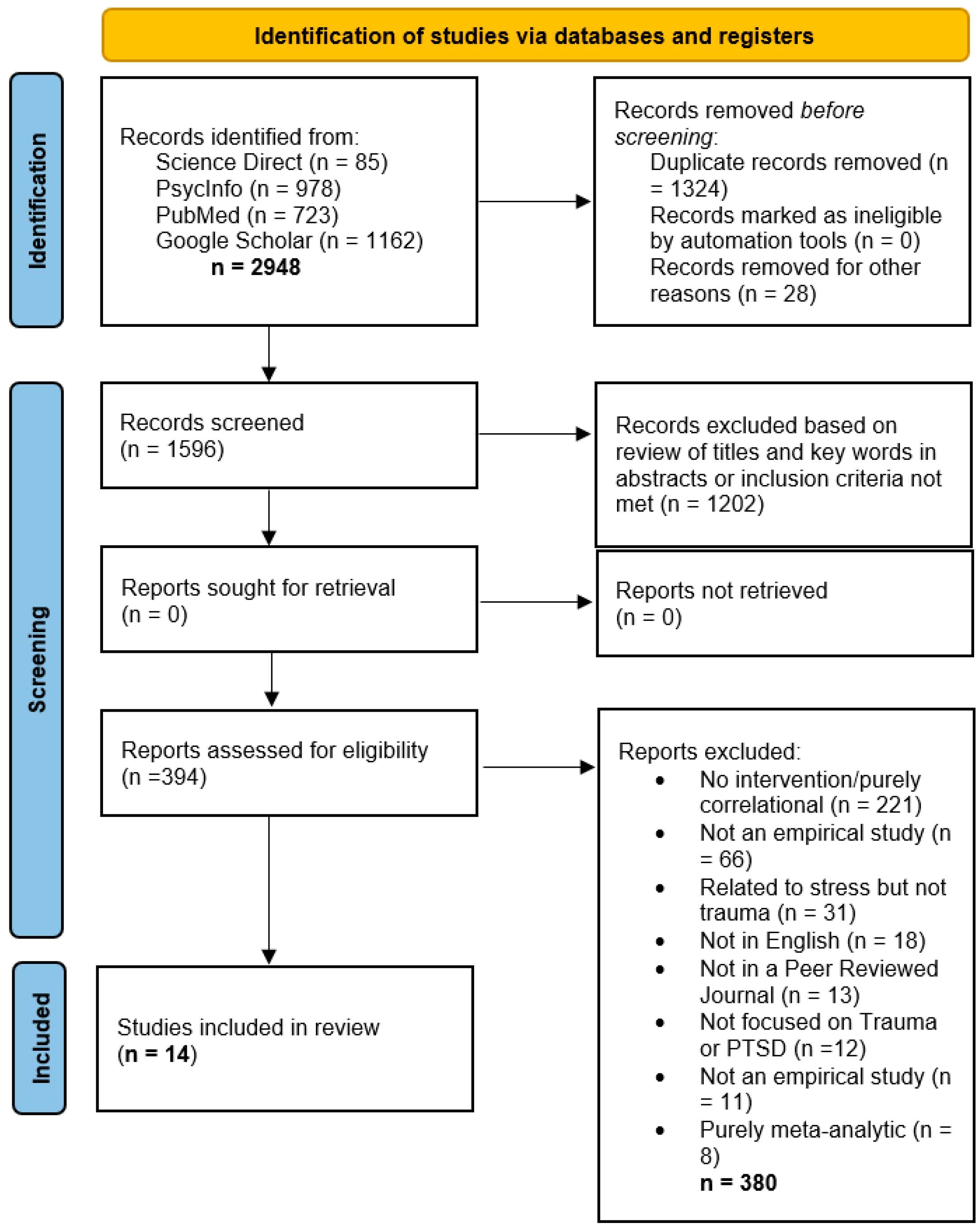

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Operationalization of Nonattachment

2.3. Screening and Data Extraction

2.4. Study Quality

3. Results

3.1. Main Findings

3.2. Overview of Included Studies

3.3. Effect Sizes and Patterns

3.4. Qualitative Insights

3.5. Cross-Sectional Analyses and Implications

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| (C)PTS (D) | (Complex) Post-Traumatic Stress (Disorder) |

| SAMHSA | Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioural Therapy |

| MBI | Mindfulness-based Intervention |

| ACT | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy |

| NTS | Nonattachment to Self |

| SQAC | Standard Quality Assessment Criteria |

| MBSR | Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction |

| DBT | Dialectical Behavioural Therapy |

| CFT | Compassion-Focused Therapy |

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Trauma and Violence—What Is Trauma and Its Effects? 2024. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/mental-health/trauma-violence (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Van der Kolk, B.A. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, G. Defining Trauma and a Trauma-Informed COVID-19 Response. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S279–S280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstow, B. A Critique of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and the DSM. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2005, 45, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, P.; Karatzias, T.; Shevlin, M.; McElroy, E.; Ben-Ezra, M.; Cloitre, M.; Brewin, C.R. Does Requiring Trauma Exposure Affect Rates of ICD-11 PTSD and Complex PTSD? Implications for DSM–5. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2021, 13, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, C.S.; Surís, A.M.; Smith, R.P.; King, R.V. The Evolution of Ptsd Criteria across Editions of Dsm. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Kolk, B.; Ford, J.D.; Spinazzola, J. Comorbidity of Developmental Trauma Disorder (DTD) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Findings from the DTD Field Trial. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2019, 10, 1562841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, I.C.; Na, P.J.; Harpaz-Rotem, I.; Marx, B.P.; Pietrzak, R.H. Prevalence, Correlates, and Burden of Subthreshold PTSD in US Veterans. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2024, 85, 24m15465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salcioglu, E.; Urhan, S.; Pirinccioglu, T.; Aydin, S. Anticipatory Fear and Helplessness Predict PTSD and Depression in Domestic Violence Survivors. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2017, 9, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.Y.Y.; Yu, B.C.L.; Mak, W.W.S. Nonattachment Mediates the Associations between Mindfulness, Well-Being, and Psychological Distress: A Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 95, 102175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, L.; Van Gordon, W.; Elander, J. Toward Greater Clarity in Defining and Understanding Nonattachment. Mindfulness 2024, 15, 1275–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahdra, B.K.; Ciarrochi, J.; Parker, P.D.; Marshall, S.; Heaven, P. Empathy and Nonattachment Independently Predict Peer Nominations of Prosocial Behavior of Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahdra, B.; Ciarrochi, J.; Parker, P. Nonattachment and Mindfulness: Related but Distinct Constructs. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present, and Future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, R.C.; Ong, C.W.; Lee, J.; Twohig, M.P. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for PTSD and Trauma: An Empirical Review. Behav. Ther. 2017, 14, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, R.; Bates, G.; Elphinstone, B.; Yang, Y. The Relative Benefits of Nonattachment to Self and Self-compassion for Psychological Distress and Psychological Well-being for Those with and without Symptoms of Depression. Psychol. Psychother. 2021, 94, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; McLean, L.; Korner, A.; Stratton, E.; Glozier, N. Mindfulness and Yoga for Psychological Trauma: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Trauma Dissociation 2020, 21, 536–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, H.J.; Bin Mahmud, M.S.; Rajendran, P.; Jiang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Wang, W. Effectiveness of Mindfulness-based Interventions on Psychological Well-being, Burnout and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder among Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 2323–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahdra, B.K.; Shaver, P.R.; Brown, K.W. A Scale to Measure Nonattachment: A Buddhist Complement to Western Research on Attachment and Adaptive Functioning. J. Personal. Assess. 2010, 92, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, R.; Bates, G.; Elphinstone, B.; Yang, Y.; Murray, G. Letting Go of Self: The Creation of the Nonattachment to Self Scale. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gordon, W.; Shonin, E.; Diouri, S.; Garcia-Campayo, J.; Kotera, Y.; Griffiths, M.D. Ontological Addiction Theory: Attachment to Me, Mine, and I. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 892–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, S.J.; Lee, W.K. Mindfulness, Non-Attachment, and Emotional Well-Being in Korean Adults. Adv. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2015, 87, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-Y.; Wong, Y.J.; Yeh, K.-H. Relationship Harmony, Dialectical Coping, and Nonattachment: Chinese Indigenous Well-Being and Mental Health. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 44, 78–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, R.; Bates, G.; Elphinstone, B. Growing by Letting Go: Nonattachment and Mindfulness as Qualities of Advanced Psychological Development. J. Adult Dev. 2020, 27, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliu-Soler, A.; Soler, J.; Luciano, J.V.; Cebolla, A.; Elices, M.; Demarzo, M.; García-Campayo, J. Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the Nonattachment Scale (NAS) and Its Relationship with Mindfulness, Decentering, and Mental Health. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 1156–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamis, D.A.; Dvorak, R.D. Mindfulness, Nonattachment, and Suicide Rumination in College Students: The Mediating Role of Depressive Symptoms. Mindfulness 2014, 5, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joss, D.; Lazar, S.W.; Teicher, M.H. Nonattachment Predicts Empathy, Rejection Sensitivity, and Symptom Reduction After a Mindfulness-Based Intervention Among Young Adults with a History of Childhood Maltreatment. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gordon, W.; Sapthiang, S.; Shonin, E. Contemplative Psychology: History, Key Assumptions, and Future Directions. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 17, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmet, L.M.; Lee, R.C.; Cook, L.S.; Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields; HTA initiative; Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Joss, D.; Khan, A.; Lazar, S.W.; Teicher, M.H. Effects of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Self-Compassion and Psychological Health Among Young Adults with a History of Childhood Maltreatment. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumarkaite, A.; Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene, I.; Andersson, G.; Mingaudaite, J.; Kazlauskas, E. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Internet Intervention on ICD-11 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 2754–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumarkaite, A.; Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene, I.; Andersson, G.; Kazlauskas, E. The Effects of Online Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms: A Randomized Controlled Trial with 3-Month Follow-Up. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 799259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, K.S.; Dick, A.M.; DiMartino, D.M.; Smith, B.N.; Niles, B.; Koenen, K.C.; Street, A. A Pilot Study of a Randomized Controlled Trial of Yoga as an Intervention for PTSD Symptoms in Women. J. Trauma. Stress 2014, 27, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, A.M.; Niles, B.L.; Street, A.E.; DiMartino, D.M.; Mitchell, K.S. Examining Mechanisms of Change in a Yoga Intervention for Women: The Influence of Mindfulness, Psychological Flexibility, and Emotion Regulation on PTSD Symptoms: Mechanisms of Change in a Yoga Intervention. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 70, 1170–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizik-Reebs, A.; Amir, I.; Yuval, K.; Hadash, Y.; Bernstein, A. Candidate Mechanisms of Action of Mindfulness-Based Trauma Recovery for Refugees (MBTR-R): Self-Compassion and Self-Criticism. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 90, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, J.G.; Shaver, P.R. Promoting Attachment-Related Mindfulness and Compassion: A Wait-List-Controlled Study of Women Who Were Mistreated During Childhood. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frewen, P.; Rogers, N.; Flodrowski, L.; Lanius, R. Mindfulness and Metta-Based Trauma Therapy (MMTT): Initial Development and Proof-of-Concept of an Internet Resource. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 1322–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Gucht, K.; Glas, J.; De Haene, L.; Kuppens, P.; Raes, F. A Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Unaccompanied Refugee Minors: A Pilot Study with Mixed Methods Evaluation. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 1084–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Gerhart, J.I.; Chesney, S.A.; Burns, J.W.; Kleinman, B.; Hood, M.M. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms: Building Acceptance and Decreasing Shame. J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 19, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, M.L.; Wilcox, M.M. Decreasing Perceived and Academic Stress through Emotion Regulation and Nonjudging with Trauma-Exposed College Students. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2020, 27, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, A.T.; Bhatta, T.R.; Muthukumar, V.; Gangozo, W.J. Testing the Acceptability and Initial Efficacy of a Smartphone-App Mindfulness Intervention for College Student Veterans with PTSD. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020, 34, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schure, M.B.; Simpson, T.L.; Martinez, M.; Sayre, G.; Kearney, D.J. Mindfulness-Based Processes of Healing for Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2018, 24, 1063–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, A.M.; Crean, H.F.; Pigeon, W.R.; Heffner, K.L. Meditation and Yoga for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 58, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harnett, N.G.; Goodman, A.M.; Knight, D.C. PTSD-Related Neuroimaging Abnormalities in Brain Function, Structure and Biochemistry. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 330, 113331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuman-Olivier, Z.; Trombka, M.; Lovas, D.A.; Brewer, J.A.; Vago, D.R.; Gawande, R.; Dunne, J.P.; Lazar, S.W.; Loucks, E.B.; Fulwiler, C. Mindfulness and Behavior Change. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, M. Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder, 3rd ed.; Diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder, 3rd ed.; Diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders; Guilford Pr: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. Introducing Compassion-Focused Therapy. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2009, 15, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Shi, J.; Li, C. Addressing Psychosomatic Symptom Distress with Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in Somatic Symptom Disorder: Mediating Effects of Self-Compassion and Alexithymia. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1289872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etingen, B.; Hessinger, J.D.; Hunley, H.A. Training Providers in Shared Decision Making for Trauma Treatment Planning. Psychol. Serv. 2022, 19, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fani, N.; Michopoulos, V.; Van Rooij, S.J.H.; Clendinen, C.; Hardy, R.A.; Jovanovic, T.; Rothbaum, B.O.; Ressler, K.J.; Stevens, J.S. Structural Connectivity and Risk for Anhedonia after Trauma: A Prospective Study and Replication. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 116, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafid, A.; Kerna, N.A. Adjunct Application of Mindfulness-Based Intervention (MBI) in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). EC Clin. Med. Case Rep. 2019, 2, 01–05. [Google Scholar]

| Study No. (Design) | Article Identifiers and SQAC Score * | Intervention Type | Population Description and Location | Control Condition (If Applicable) | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Randomised Controlled Trial/RCT) | Effects of a MBI on Self-Compassion and psychological Health Among Young Adults with a History of Childhood Maltreatment [32]. 80% | MBSR, 8 weeks × 2.5 h plus 1 full day/week | n = 38, age 22–29, individuals who were maltreated in childhood. USA. | Waitlist (n = 18) | MBSR can improve self-compassion and psychological health |

| 2 (RCT) | Nonattachment predicts Empathy, Rejection Sensitivity, and Symptom Reduction after a MBI Among Young Adults with a History of Childhood Maltreatment [28]. 80% | MBSR, 8 weeks × 2.5 h plus 1 full day/week | n = 38, age 22–29, individuals who were maltreated in childhood. USA. | Waitlist (n = 18) | MBSR can improve mindfulness, Nonattachment and empathy which can impact interpersonal distress and rejection sensitivity |

| 3 (RCT) | Effects of a MBI on ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD Symptoms: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial [33]. 88% | Novel MBI based on principles of awareness and nonjudgement of physical senses, thoughts, and emotions. 8 weeks of 1 meditation/day lasting 2–7 min | n = 70, age 20–35 meeting criteria for PTSD, CPTSD or Disturbances in self-organization. Lithuania. | Waitlist (n = 39). Could access the program after 5 months | MBI can reduce CPTSD symptoms and have positive effects on overall mental health. Internet-based interventions seem effective for certain types of trauma care |

| 4 (RCT) | The effects of Online MBI on PTSD and CPTSD Symptoms: A Randomized Controlled Trial with 3-Month Follow-Up [34]. 88% | Novel MBI based on principles of awareness and nonjudgement of physical senses, thoughts, and emotions. 8 weeks of 1 meditation/day lasting 2–7 min | n = 70, age 20–35 meeting criteria for PTSD, CPTSD or Disturbances in self-organization. Lithuania | Waitlist (n = 39). Could access the program after 5 months | Effects of MBI for PTSD and CPTSD symptoms retained over time (3 months) |

| 5 (RCT) | A Pilot Study of a RCT of Yoga as an Intervention for PTSD Symptoms in Women [35]. 87.5% | Yoga-based intervention. 12 weeks with 1 × 75 min/week or 6 weeks with 2 × 75 min | n = 38, mean age = 44 veteran and civilian adult females with full or subthreshold PTSD symptoms. USA. | Waitlist (n = 18) completed same weekly questionnaires as exp condition in weekly group meetings | Yoga intervention yielded decreases in reexperiencing and hyperarousal. Intervention is tolerable and may be an effective adjunctive intervention for this population. |

| 6 (RCT) | Examining Mechanisms of Change in a Yoga Intervention for Women: The Influence of Mindfulness, Psychological Flexibility, and Emotion Regulation on PTSD symptoms [36]. 87.5% | Yoga-based intervention. 12 weeks with 1 × 75 min/week or 6 weeks with 2 × 75 min | n = 38, mean age = 44 veteran and civilian adult females with full or subthreshold PTSD symptoms. USA. | Waitlist (n = 18) completed same weekly questionnaires as exp condition in weekly group meetings | Yoga may reduce expressive suppression and improve PTSD symptoms. Psychological flexibility increased for control but not exp group, counter to predictions. |

| 7 (RCT) | Candidate Mechanisms of Action of Mindfulness-Based Trauma Recovery for Refugees: Self-Compassion and Self-Criticism [37]. 83% | Mindfulness-based Trauma Recovery for Refugees. 9 weeks × 2.5 h | n = 158, age = 20–48, traumatized East-African asylum-seekers residing in Israel. | Waitlist (ratio of 3:2 exp to control) who were able to access intervention after exp completion | Intervention yielded improvements in self-compassion and reductions in self-criticism. Findings indicated importance of self-referentiality as a target mechanism in MBIs and trauma recovery. |

| 8 (Quasi Experimental) | Promoting Attachment-Related Mindfulness and Compassion: a Wait-List Controlled Study of Women Who Were Mistreated During Childhood [38]. 75% | REAC2H program focused on mind, thoughts, and emotions over a 3-day × 8 h intensive | n = 17, age 18–80 participants who self-reported childhood maltreatment. | Waitlist n = 22 | Significant improvements in rumination, emotion suppression, emotion regulation, clarity of emotions, and mindfulness. |

| 9 (Cross-Sectional) | Mindfulness and Metta-Based Trauma Therapy (MMTT): Initial Development and Proof-of-Concept of an Internet Resource [39]. 92.5% | Novel Metta based trauma therapy where one engagement constituted participation with unlimited access for 6 months | n = 177, age 18–75 participants who self-reported suffering from PTSD symptoms using PCL-5 assessment. Canada. | None | Participants reported utility of intervention as credible and helpful for improving self-regulation, wellbeing, and mitigating PTSD, anxiety, depression, and dissociation. Participants with higher PTSD symptoms enjoyed metta meditations less than those with less intense symptoms |

| 10 (Cohort-mixed method) | A MBI for Unaccompanied Refugee Minors: A Pilot Study with Mixed Methods Evaluation [40]. 81.8% | MBSR-MBCT Hybrid with 8 weeks × 90 min | n = 13 aged 13–18, who were unaccompanied minor refugees. Belgium. | None | MBI may decrease negative and increase positive affect and reduce symptoms of depression. Mindfulness exercises may be used as a coping strategy |

| 11 (Cohort) | MBSR for PTS Symptoms: Building Acceptance and Decreasing Shame [41]. 90.9% | MBSR with 8 sessions said to have followed MBSR guidelines, but unspecified in duration | n = 9, average age = 44, adults who reported trauma exposure, PTS, or depression. USA. | None | PTS, depression, and shame-based trauma appraisals decreased. Acceptance of emotional experiences increased. Reducing shame and increasing acceptance may be important in trauma recovery |

| 12 (Cohort) | Decreasing Perceived and Academic Stress Through Emotion Regulation and Nonjudging with Trauma-Exposed College Students [42]. 88% | Novel MBI focused on enhancing emotional regulation and nonjudgement to reduce stress with 3 weeks × 10 min meditations (1/week) | n = 209, age 18–42 undergraduate students who reported trauma exposure. USA. | No description | A brief MBI can reduce academic and perceived stress through emotional regulation and increasing nonjudgement. Perceived stress was only reduced in participants with subthreshold PTSD |

| 13 (Cohort) | Testing the Acceptability and Initial Efficacy of a Smart-phone App Mindfulness Intervention for College Student Veterans with PTSD [43]. 86% | Novel MBI with elements of ACT for 4 weeks with at least one meditation per day (6–19 min long) plus weekly phone check-ins | n = 23, age 23–43 student veterans | None | App delivery was favourably rated. Improvements noted in resilience, mindfulness, PTSD symptoms, experiential avoidance, and rumination |

| 14 (Qualitative, using semi-structured interviews) | Mindfulness-Based Process of Healing for Veterans with PTSD [44]. 80% | MBSR with 8 weeks × 2.5 h and 1 full day/week. | n = 15, age unspecified, veterans with a PTSD diagnosis. USA. | None | Six core aspects of MBSR experience were identified, including: dealing with past, staying in present, acceptance of adversity, breathing through stress, relaxation, and openness to self and others. Introspection and curiosity may have been activated by MBSR participation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tremblay, L.; Van Gordon, W.; Elander, J. Enhancing Traumatic Stress Recovery Through Nonattachment Principles: A Scoping Review. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120614

Tremblay L, Van Gordon W, Elander J. Enhancing Traumatic Stress Recovery Through Nonattachment Principles: A Scoping Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):614. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120614

Chicago/Turabian StyleTremblay, Lindsay, William Van Gordon, and James Elander. 2025. "Enhancing Traumatic Stress Recovery Through Nonattachment Principles: A Scoping Review" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120614

APA StyleTremblay, L., Van Gordon, W., & Elander, J. (2025). Enhancing Traumatic Stress Recovery Through Nonattachment Principles: A Scoping Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120614