The Personalized Management of Primary Biliary Cholangitis in the Era of Precision Medicine: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Background

1.1. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: When the Disease Definition Can Illustrate the Etiopathogenesis

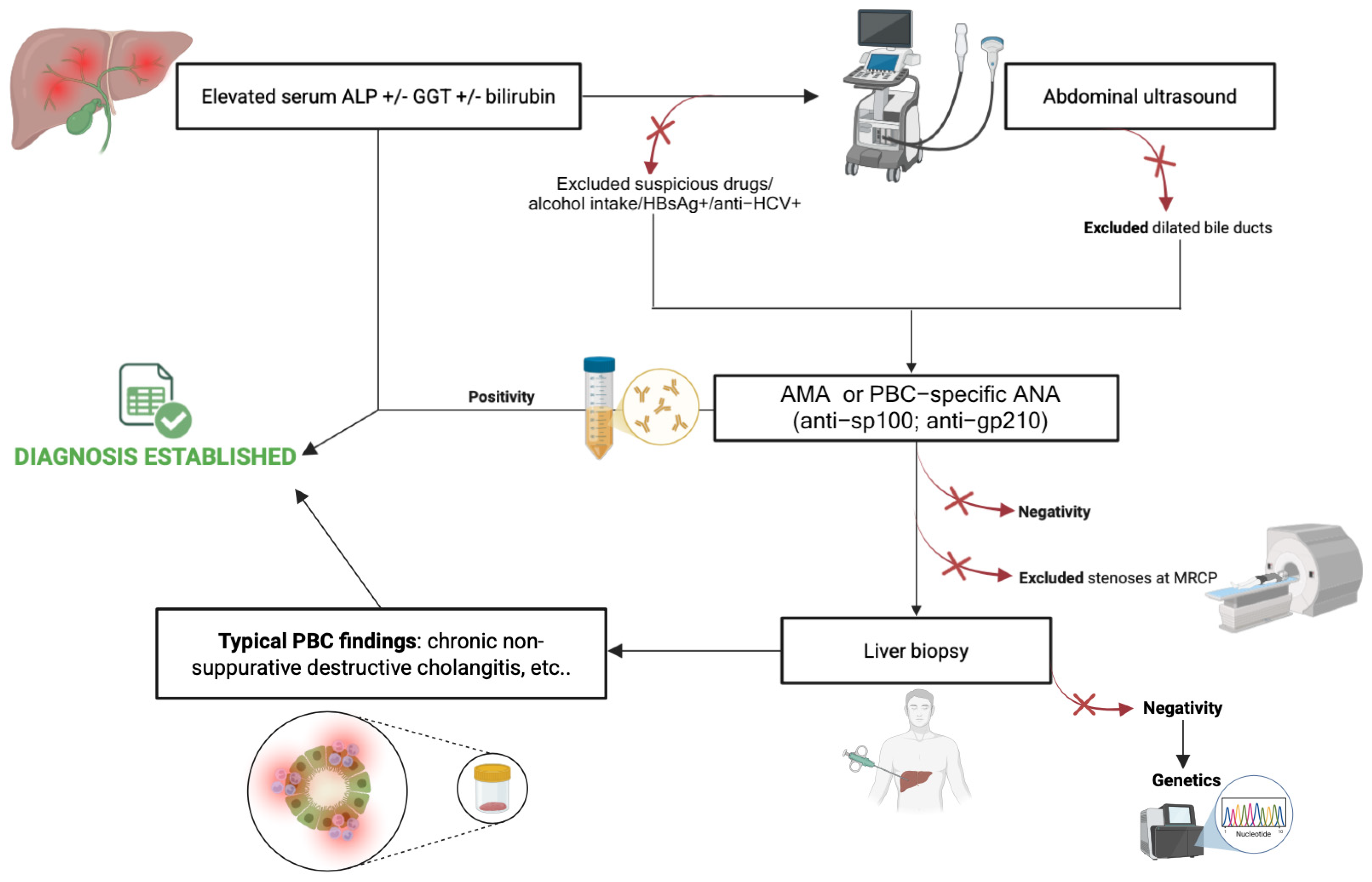

1.2. Primary Biliary Cholangitis Diagnosis: Redefining the Current Role of Liver Biopsy

1.3. Personalizing the Management Strategies for Primary Biliary Cholangitis: An Urgent Need

2. Therapeutic Opportunities to Treat Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Today’s Certainties and Tomorrow’s Challenges

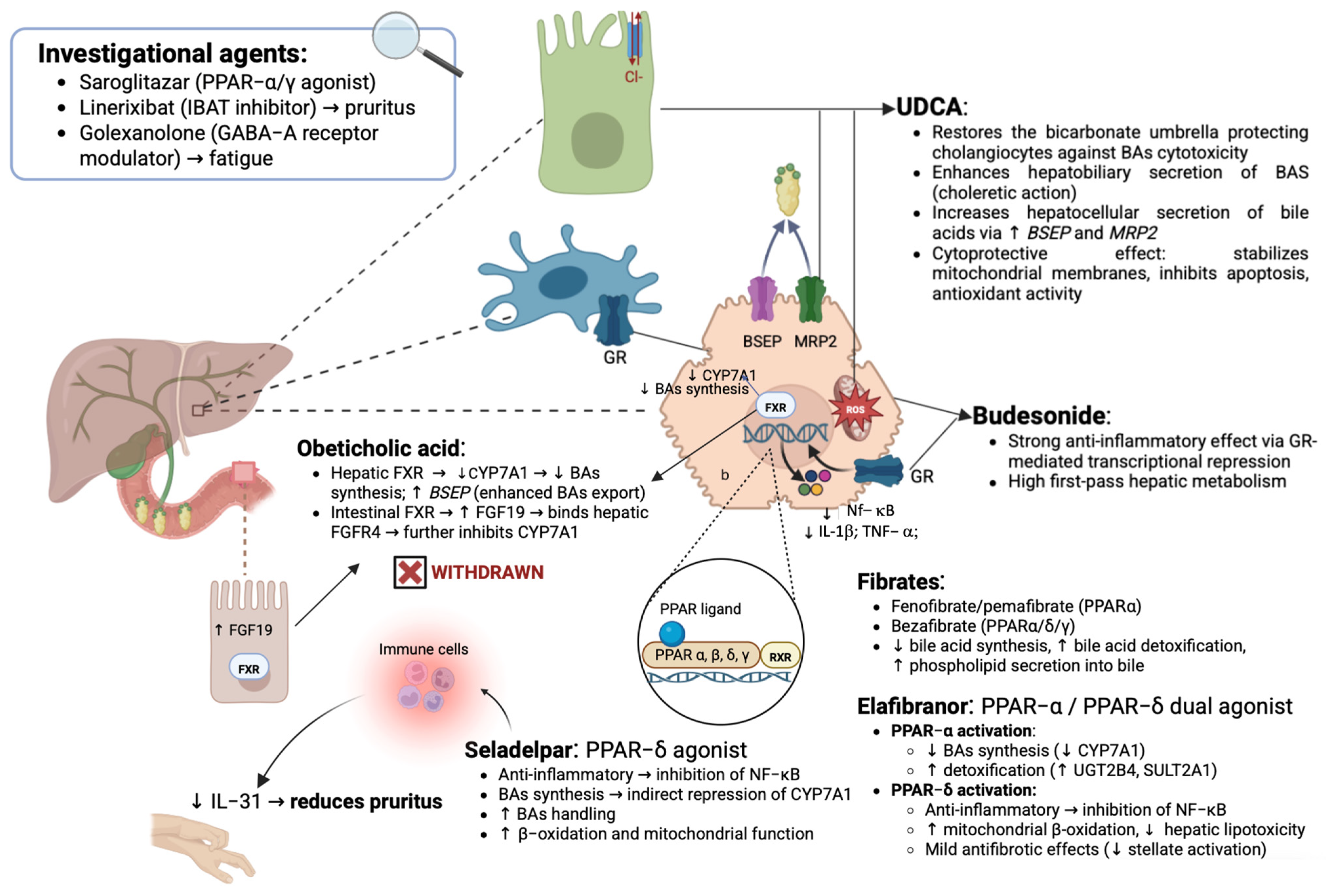

2.1. Ursodeoxycholic Acid (UDCA): The Mainstay of Therapy in Primary Biliary Cholangitis

2.2. Beyond Ursodeoxycholic Acid: Lights, Shadows, and Promises of Second-Line Therapies in PBC

2.2.1. Role of Budesonide in the Treatment of PBC and Relative Limitations

2.2.2. Obeticholic Acid: Initial Enthusiasm Culminated in a Cruel Twist and Unfortunate Fate

2.2.3. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors as a Crucial Target for PBC Therapy

Fibrates: Mechanisms and Indications of “Classic” PPAR Agonists in PBC

Next-Generation PPAR Ligands: Status of the Art

2.3. Future Therapies in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Dynamic and Evolving Drug Pipeline

3. Predicting Disease Course in Primary Biliary Cholangitis in the Era of Noninvasive Tools

3.1. Role of Demographic and Clinical Profile

3.2. Role of Routine Hepatic Tests

3.3. Role of Serological Markers: Defining the Impact of PBC-Associated Autoantibodies

3.4. Role of Histological Features

3.5. Role of Noninvasive Tools

3.5.1. Role of Biomarkers

3.5.2. Role of Elastography-Based Methods

3.6. Predicting Treatment Response in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: An Evolving Challenge

3.6.1. Composite Models Predicting Treatment Response in PBC

3.6.2. Models for Pre-Treatment Prediction of Response: Role of Multivariate Risk Scores

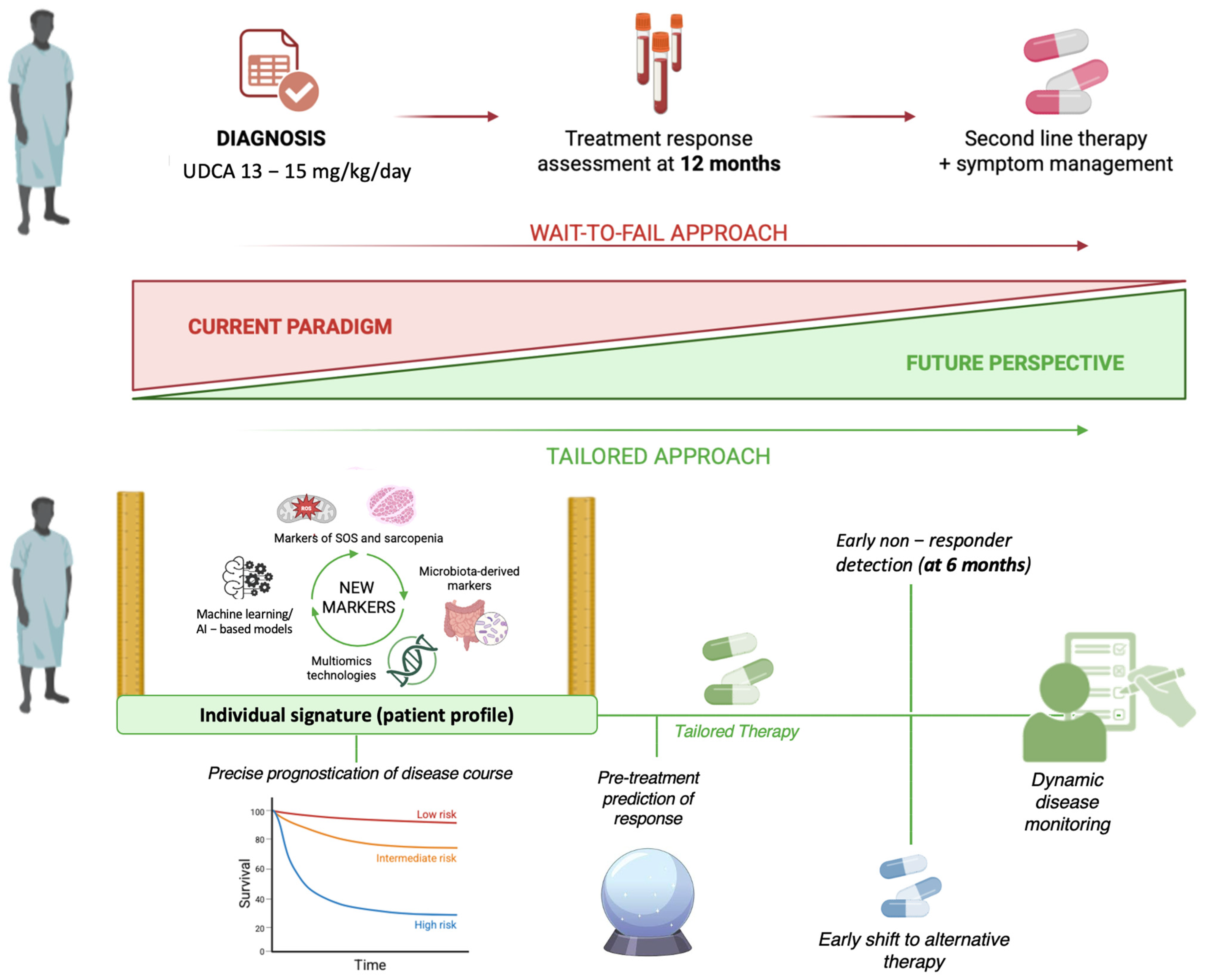

4. Future Perspectives in Managing PBC: From One-Size-Fits-All to Tailored Approaches

4.1. Time for New Markers: The Emerging Role of Multiomics in Predicting PBC Individual Evolution

4.2. Microbiota-Derived Markers Composing Signatures to Predict Individual PBC Evolution

4.3. Systemic Oxidative Stress Markers: PBC Hepatic Progression and Extra-Hepatic Manifestations

4.4. Clinical and Translational Implications of Emerging Biomarkers

4.5. Body Composition Parameters and Liver Density as Emerging Prognostic Tools in PBC

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACA | Anti-centromere antibodies |

| AIH | Autoimmune hepatitis |

| ALBI | Albumin–Bilirubin score |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AMA | Antimitochondrial antibodies |

| AMA-M2 | Antimitochondrial antibodies subtype M2 |

| ANA | Antinuclear antibodies |

| AAR | AST/ALT ratio |

| APRI | AST-to-platelet ratio index |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| BAP | Biological Antioxidant Potential |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CAP | Controlled attenuation parameter |

| CSPH | Clinically significant portal hypertension |

| CTP | Child–Turcotte–Pugh score |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| ELF | Enhanced Liver Fibrosis score |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| ESLD | End-stage liver disease |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| FXR | Farnesoid X receptor |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyltransferase |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association studies |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| HVPG | Hepatic venous pressure gradient |

| IBAT | Ileal bile acid transporter |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| IgM | Immunoglobulin M |

| KLHL12 | Kelch-like 12 |

| LREs | Liver-related events |

| LSM | Liver stiffness measurement |

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| MELD | Model for End-stage Liver Disease |

| miR- | MicroRNA |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MRE | Magnetic resonance elastography |

| MRCP | Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography |

| MRS | Mayo Risk Score |

| NITs | Non-invasive tools |

| NRF2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| OCA | Obeticholic acid |

| PBC | Primary biliary cholangitis |

| PDC-E2 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex E2 subunit |

| PH | Portal hypertension |

| PPAR | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RPR | Red blood cell distribution width to platelet ratio |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| SMD | Skeletal muscle density |

| SMI | Skeletal muscle index |

| SOS | Systemic oxidative stress |

| SSM | Spleen stiffness measurement |

| TE | Transient elastography |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor beta 1 |

| ULN | Upper limit of normal |

| URS | UDCA Response Score |

| UDCA | Ursodeoxycholic acid |

| UK-PBC | United Kingdom Primary Biliary Cholangitis |

References

- Sarcognato, S.; Sacchi, D.; Grillo, F.; Cazzagon, N.; Fabris, L.; Cadamuro, M.; Cataldo, I.; Covelli, C.; Mangia, A.; Guido, M. Autoimmune Biliary Diseases: Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Pathologica 2021, 113, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleo, A.; Colapietro, F. Changes in the Epidemiology of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Clin. Liver Dis. 2018, 22, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, M.; Mansour, N.; John, B.V. Primary Biliary Cholangitis in Males: Pathogenesis, Clinical Presentation, and Prognosis. Clin. Liver Dis. 2022, 26, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmi, C.; Mayo, M.J.; Bach, N.; Ishibashi, H.; Invernizzi, P.; Gish, R.G.; Gordon, S.C.; Wright, H.I.; Zweiban, B.; Podda, M.; et al. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis in Monozygotic and Dizygotic Twins: Genetics, Epigenetics, and Environment. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordell, H.J.; Fryett, J.J.; Ueno, K.; Darlay, R.; Aiba, Y.; Hitomi, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Nishida, N.; Khor, S.-S.; Gervais, O.; et al. An International Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis of Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Novel Risk Loci and Candidate Drugs. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, S.; Yang, H.; Zhong, W.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Chu, H.; et al. Novel HLA-DRB1 Alleles Contribute Risk for Disease Susceptibility in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2022, 54, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulamhusein, A.F.; Juran, B.D.; Lazaridis, K.N. Genome-Wide Association Studies in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Semin. Liver Dis. 2015, 35, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, J.; He, L.; Zhang, F. MicroRNA-34a Promotes EMT and Liver Fibrosis in Primary Biliary Cholangitis by Regulating TGF-Β1/Smad Pathway. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 6890423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tang, R.; Ma, X. Epigenetics of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1253, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juran, B.D.; Lazaridis, K.N. Environmental Factors in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Semin. Liver Dis. 2014, 34, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmi, C.; Gershwin, M.E. The Role of Environmental Factors in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Trends Immunol. 2009, 30, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probert, P.M.; Leitch, A.C.; Dunn, M.P.; Meyer, S.K.; Palmer, J.M.; Abdelghany, T.M.; Lakey, A.F.; Cooke, M.P.; Talbot, H.; Wills, C.; et al. Identification of a Xenobiotic as a Potential Environmental Trigger in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 1123–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijarnpreecha, K.; Werlang, M.; Panjawatanan, P.; Kroner, P.T.; Mousa, O.Y.; Pungpapong, S.; Lukens, F.J.; Harnois, D.M.; Ungprasert, P. Association between Smoking and Risk of Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2019, 28, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijarnpreecha, K.; Werlang, M.; Panjawatanan, P.; Pungpapong, S.; Lukens, F.J.; Harnois, D.M.; Ungprasert, P. Smoking & Risk of Advanced Liver Fibrosis among Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis. Indian. J. Med. Res. 2021, 154, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.-Y.; Zhang, F.-C. Role of Autoimmunity in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 7141–7148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouroumalis, E.; Notas, G. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: From Bench to Bedside. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 6, 32–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Invernizzi, P.; Selmi, C.; Gershwin, M.E. Update on Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2010, 42, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gulamhusein, A.F.; Hirschfield, G.M. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Opportunities. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guan, Y.; Han, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wei, W.; Ma, Y. The Pathogenesis, Models and Therapeutic Advances of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 140, 111754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlus, C.L.; Gershwin, M.E. The Diagnosis of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2014, 13, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Ma, X.; Efe, C.; Wang, G.; Jeong, S.-H.; Abe, K.; Duan, W.; Chen, S.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, D.; et al. APASL Clinical Practice Guidance: The Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Hepatol. Int. 2022, 16, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-A.; Jeong, S.-H. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Korean J. Hepatol. 2011, 17, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Ma, X.; Yokosuka, O.; Weltman, M.; You, H.; Amarapurkar, D.N.; Kim, Y.J.; Abbas, Z.; Payawal, D.A.; Chang, M.-L.; et al. Autoimmune Liver Diseases in the Asia-Pacific Region: Proceedings of APASL Symposium on AIH and PBC 2016. Hepatol. Int. 2016, 10, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Bernstein, D.; Shiffman, M.L.; Kwo, P.; Kim, W.R.; Kowdley, K.V.; Jacobson, I.M. Diagnosis and Management of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigopoulou, E.I.; Bogdanos, D.P. Role of Autoantibodies in the Clinical Management of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 1795–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofrio, F.Q.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Gulamhusein, A.F. A Practical Review of Primary Biliary Cholangitis for the Gastroenterologist. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 15, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Trivella, J.; John, B.V.; Levy, C. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Epidemiology, Prognosis, and Treatment. Hepatol. Commun. 2023, 7, e0179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli, B.; Stirnimann, G.; Mertens, J.; Semela, D.; Zen, Y.; Mazzucchelli, L.; Voreck, A.; Kolbus, N.; Merlo, E.; Di Bartolomeo, C.; et al. Primary Biliary Cholangitis with Normal Alkaline Phosphatase: A Neglected Clinical Entity Challenging Current Guidelines. J. Autoimmun. 2021, 116, 102578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschfield, G.M.; Dyson, J.K.; Alexander, G.J.M.; Chapman, M.H.; Collier, J.; Hübscher, S.; Patanwala, I.; Pereira, S.P.; Thain, C.; Thorburn, D.; et al. The British Society of Gastroenterology/UK-PBC Primary Biliary Cholangitis Treatment and Management Guidelines. Gut 2018, 67, 1568–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Duan, W.; Li, S.; Lv, T.; Chen, S.; Lu, L.; Ma, X.; Han, Y.; Nan, Y.; Xu, X.; et al. Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Primary Biliary Cholangitis (2021). J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2023, 11, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-J.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.-G.; Jiang, Y.; Cheng, X.-J.; Han, X.; Wang, C.-Y.; Li, J. Role of Biochemical Markers and Autoantibodies in Diagnosis of Early-Stage Primary Biliary Cholangitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 5075–5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, R.; Mahtab, M.-A.; Al Mamun, A.; Kumar Saha, B.; Shahadat Hossain, S.M.; Chandra Das, D.; Fazle Akbar, S.M.; Kamal, M.; Rahman, S. A Case of Antimitochondrial Antibody Negative Primary Biliary Cirrhosis from Bangladesh and Review of Literature. Euroasian J. Hepato-Gastroenterol. 2015, 5, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhu, W.; Yin, Y. Diagnostic Value of Anti-Mitochondrial Antibody in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2023, 102, e36039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Goodman, Z.D. Liver Biopsy in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Indications and Interpretation. Clin. Liver Dis. 2018, 22, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, M.H.; Janssen, Q.P.; Adam, R.; Duvoux, C.; Mirza, D.; Hidalgo, E.; Watson, C.; Wigmore, S.J.; Pinzani, M.; Isoniemi, H.; et al. Trends in Liver Transplantation for Primary Biliary Cholangitis in Europe over the Past Three Decades. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 49, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzakis, A.G.; Carcassonne, C.; Todo, S.; Makowka, L.; Starzl, T.E. Liver Transplantation for Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Semin. Liver Dis. 1989, 9, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, A.; Ma, X.; Takahashi, A.; Vierling, J.M. Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Lancet 2024, 404, 1053–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, M.J.; Carey, E.; Smith, H.T.; Mospan, A.R.; McLaughlin, M.; Thompson, A.; Morris, H.L.; Sandefur, R.; Kim, W.R.; Bowlus, C.; et al. Impact of Pruritus on Quality of Life and Current Treatment Patterns in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallio, M.; Romeo, M.; Di Nardo, F.; Napolitano, C.; Vaia, P.; Ventriglia, L.; Coppola, A.; Olivieri, S.; Niosi, M.; Federico, A. Systemic Oxidative Stress Correlates with Sarcopenia and Pruritus Severity in Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC): Two Independent Relationships Simultaneously Impacting the Quality of Life—Is the Low Absorption of Cholestasis-Promoted Vitamin D a Puzzle Piece? Livers 2024, 4, 656–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeki, C.; Oikawa, T.; Kanai, T.; Nakano, M.; Torisu, Y.; Sasaki, N.; Abo, M.; Saruta, M.; Tsubota, A. Relationship between Osteoporosis, Sarcopenia, Vertebral Fracture, and Osteosarcopenia in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, J.S.; Grandhe, S.; Matsukuma, K.; Bowlus, C.L. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Brief Overview. Clin. Liver Dis. 2020, 15, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristoferi, L.; Nardi, A.; Ronca, V.; Invernizzi, P.; Mells, G.; Carbone, M. Prognostic Models in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J. Autoimmun. 2018, 95, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpechot, C.; Poupon, R.; Chazouillères, O. New Treatments/Targets for Primary Biliary Cholangitis. JHEP Rep. 2019, 1, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koky, T.; Drazilova, S.; Janicko, M.; Toporcerova, D.; Gazda, J.; Jarcuska, P. Early Assessment of Treatment Response in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Key to Timely Management. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo Perez, C.F.; Harms, M.H.; Lindor, K.D.; van Buuren, H.R.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Corpechot, C.; van der Meer, A.J.; Feld, J.J.; Gulamhusein, A.; Lammers, W.J.; et al. Goals of Treatment for Improved Survival in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Treatment Target Should Be Bilirubin Within the Normal Range and Normalization of Alkaline Phosphatase. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cançado, G.G.L.; Lleo, A.; Levy, C.; Trauner, M.; Hirschfield, G.M. Primary Biliary Cholangitis and the Narrowing Gap towards Optimal Disease Control. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 10, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sylvia, D.; Tomas, K.; Marian, M.; Martin, J.; Dagmar, S.; Peter, J. The Treatment of Primary Biliary Cholangitis: From Shadow to Light. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2024, 17, 17562848241265782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizaki, K.; Imada, T.; Tsurufuji, M. Hepatoprotective Bile Acid “ursodeoxycholic Acid (UDCA)” Property and Difference as Bile Acids. Hepatol. Res. 2005, 33, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beuers, U.; Trampert, D.C. Ursodeoxycholic acid: History and clinical implications. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2022, 166, D6970. [Google Scholar]

- Okada, K.; Shoda, J.; Taguchi, K.; Maher, J.M.; Ishizaki, K.; Inoue, Y.; Ohtsuki, M.; Goto, N.; Takeda, K.; Utsunomiya, H.; et al. Ursodeoxycholic Acid Stimulates Nrf2-Mediated Hepatocellular Transport, Detoxification, and Antioxidative Stress Systems in Mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008, 295, G735–G747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Bowlus, C.L. Treatment of Primary Biliary Cholangitis: First-Line and Second-Line Therapies. Clin. Liver Dis. 2022, 26, 705–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poupon, R.E.; Balkau, B.; Eschwège, E.; Poupon, R. A Multicenter, Controlled Trial of Ursodiol for the Treatment of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. UDCA-PBC Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 1548–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combes, B.; Carithers, R.L.; Maddrey, W.C.; Lin, D.; McDonald, M.F.; Wheeler, D.E.; Eigenbrodt, E.H.; Muñoz, S.J.; Rubin, R.; Garcia-Tsao, G. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Ursodeoxycholic Acid in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 1995, 22, 759–766. [Google Scholar]

- Parés, A.; Caballería, L.; Rodés, J.; Bruguera, M.; Rodrigo, L.; García-Plaza, A.; Berenguer, J.; Rodríguez-Martínez, D.; Mercader, J.; Velicia, R. Long-Term Effects of Ursodeoxycholic Acid in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Results of a Double-Blind Controlled Multicentric Trial. UDCA-Cooperative Group from the Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver. J. Hepatol. 2000, 32, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harms, M.H.; van Buuren, H.R.; Corpechot, C.; Thorburn, D.; Janssen, H.L.A.; Lindor, K.D.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Parés, A.; Floreani, A.; Mayo, M.J.; et al. Ursodeoxycholic Acid Therapy and Liver Transplant-Free Survival in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.A.; Kowdley, K.V. Current and Potential Treatments for Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpechot, C.; Abenavoli, L.; Rabahi, N.; Chrétien, Y.; Andréani, T.; Johanet, C.; Chazouillères, O.; Poupon, R. Biochemical Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid and Long-Term Prognosis in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2008, 48, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, E.M.M.; Hansen, B.E.; de Vries, R.A.; den Ouden-Muller, J.W.; van Ditzhuijsen, T.J.M.; Haagsma, E.B.; Houben, M.H.M.G.; Witteman, B.J.M.; van Erpecum, K.J.; van Buuren, H.R.; et al. Improved Prognosis of Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis That Have a Biochemical Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.A.; Bahar, R.; Liu, C.H.; Bowlus, C.L. Current Treatment Options for Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Clin. Liver Dis. 2018, 22, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örnolfsson, K.T.; Lund, S.H.; Olafsson, S.; Bergmann, O.M.; Björnsson, E.S. Biochemical Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid among PBC Patients: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 54, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Wang, J.-X.; Liu, Y.-J. Optimal Drug Regimens for Improving ALP Biochemical Levels in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis Refractory to UDCA: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenco-Flores, A.; Rojas Amaris, N.; Kahan, T.; Sierra, L.; Barba Bernal, R.; Medina-Morales, E.; Goyes, D.; Patwardhan, V.; Bonder, A. The External Validation of GLOBE and UK-PBC Risk Scores for Predicting Ursodeoxycholic Acid Treatment Response in a Large U.S. Cohort of Primary Biliary Cholangitis Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.X.; Li, B.E.; Li, M.; Chen, S.; Lyu, T.T.; Wang, Q.Y.; Wang, X.M.; Wang, Y.; Ma, H.; Ou, X.J.; et al. GLOBE Score and UK-PBC Risk Score Predict Long-Term Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Receiving Ursodeoxycholic Acid and Fenofibrate. J. Dig. Dis. 2025, 26, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautiainen, H.; Kärkkäinen, P.; Karvonen, A.-L.; Nurmi, H.; Pikkarainen, P.; Nuutinen, H.; Färkkilä, M. Budesonide Combined with UDCA to Improve Liver Histology in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: A Three-Year Randomized Trial. Hepatology 2005, 41, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuschner, M.; Maier, K.P.; Schlichting, J.; Strahl, S.; Herrmann, G.; Dahm, H.H.; Ackermann, H.; Happ, J.; Leuschner, U. Oral Budesonide and Ursodeoxycholic Acid for Treatment of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Results of a Prospective Double-Blind Trial. Gastroenterology 1999, 117, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, M.; Cipullo, M.; Iadanza, G.; Olivieri, S.; Gravina, A.G.; Pellegrino, R.; Panarese, I.; Dallio, M.; Federico, A. A 60-Year-Old Woman with Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Crohn’s Ileitis Following the Suspension of Ursodeoxycholic Acid. Am. J. Case Rep. 2022, 23, e936387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hempfling, W.; Grunhage, F.; Dilger, K.; Reichel, C.; Beuers, U.; Sauerbruch, T. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamic Action of Budesonide in Early- and Late-Stage Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2003, 38, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfield, G.M.; Beuers, U.; Kupcinskas, L.; Ott, P.; Bergquist, A.; Färkkilä, M.; Manns, M.P.; Parés, A.; Spengler, U.; Stiess, M.; et al. A Placebo-Controlled Randomised Trial of Budesonide for PBC Following an Insufficient Response to UDCA. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.E.J. Obeticholic Acid for the Treatment of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Expert. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 10, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.H.; Lindor, K.D. Obeticholic Acid for the Treatment of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2016, 17, 1809–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, M.J. Mechanisms and Molecules: What Are the Treatment Targets for Primary Biliary Cholangitis? Hepatology 2022, 76, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.J.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Gershwin, M.E. Obeticholic Acid for the Treatment of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Expert. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 9, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, F.; Andreone, P.; Mazzella, G.; Strasser, S.I.; Bowlus, C.; Invernizzi, P.; Drenth, J.P.H.; Pockros, P.J.; Regula, J.; Beuers, U.; et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Obeticholic Acid in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, A.; Keam, S.J. Obeticholic Acid: First Global Approval. Drugs 2016, 76, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, J.E.; Gores, G.J. Long-Term Outcomes with Obeticholic Acid in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Reassuring, but Still an Itch We Need to Scratch. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 417–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phaw, N.A.; Dyson, J.K.; Jones, D. Emerging Drugs for the Treatment of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Expert. Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2020, 25, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floreani, A.; Gabbia, D.; De Martin, S. Obeticholic Acid for Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowdley, K.V.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Coombs, C.; Malecha, E.S.; Bessonova, L.; Li, J.; Rathnayaka, N.; Mells, G.; Jones, D.E.; Trivedi, P.J.; et al. COBALT: A Confirmatory Trial of Obeticholic Acid in Primary Biliary Cholangitis with Placebo and External Controls. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 120, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.E.J.; Beuers, U.; Bonder, A.; Carbone, M.; Culver, E.; Dyson, J.; Gish, R.G.; Hansen, B.E.; Hirschfield, G.; Jones, R.; et al. Primary Biliary Cholangitis Drug Evaluation and Regulatory Approval: Where Do We Go from Here? Hepatology 2024, 80, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofides, A.; Konstantinidou, E.; Jani, C.; Boussiotis, V.A. The Role of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors (PPAR) in Immune Responses. Metabolism 2021, 114, 154338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghonem, N.S.; Assis, D.N.; Boyer, J.L. Fibrates and Cholestasis. Hepatology 2015, 62, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zheng, K.; Da, G.; Wang, X.; Wei, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L. Revisiting PPAR Agonists: Novel Perspectives in the Treatment of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2024, 25, 1825–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colapietro, F.; Gershwin, M.E.; Lleo, A. PPAR Agonists for the Treatment of Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Old and New Tales. J. Transl. Autoimmun. 2023, 6, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Zollner, G.; Trauner, M. Nuclear Receptors in Liver Disease. Hepatology 2011, 53, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, T.; Nakamura, H.; Harano, Y.; Yamauchi, N.; Morita, A.; Kirishima, T.; Minami, M.; Itoh, Y.; Okanoue, T. PPARalpha Ligands Activate Antioxidant Enzymes and Suppress Hepatic Fibrosis in Rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 324, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, C. Fibrates for Primary Biliary Cholangitis: What’s All the Hype? Ann. Hepatol. 2017, 16, 704–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpechot, C. The Role of Fibrates in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Curr. Hepatol. Rep. 2019, 18, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezafibrate for Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Efficacy, Safety, and Efficiency of an off-Label Use Protocol in Real-World Practice—Cerca Con Google. Available online: https://ejhp.bmj.com/content/32/Suppl_1/A129.2 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Corpechot, C.; Chazouillères, O.; Rousseau, A.; Le Gruyer, A.; Habersetzer, F.; Mathurin, P.; Goria, O.; Potier, P.; Minello, A.; Silvain, C.; et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Bezafibrate in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2171–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, S.; Akisawa, N.; Saibara, T.; Onishi, S. Fibrate for Treatment of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatol. Res. 2007, 37 (Suppl. S3), S515–S517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Hirohara, J.; Nakano, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Chazouillères, O.; Takikawa, H.; Hansen, B.E.; Carrat, F.; Corpechot, C. Association of Bezafibrate with Transplant-Free Survival in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosonuma, K.; Sato, K.; Yamazaki, Y.; Yanagisawa, M.; Hashizume, H.; Horiguchi, N.; Kakizaki, S.; Kusano, M.; Yamada, M. A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study of Long-Term Combination Therapy Using Ursodeoxycholic Acid and Bezafibrate in Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis and Dyslipidemia. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindor, K.D.; Bowlus, C.L.; Boyer, J.; Levy, C.; Mayo, M. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: 2021 Practice Guidance Update from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2022, 75, 1012–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratziu, V.; Harrison, S.A.; Francque, S.; Bedossa, P.; Lehert, P.; Serfaty, L.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Boursier, J.; Abdelmalek, M.; Caldwell, S.; et al. Elafibranor, an Agonist of the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-α and -δ, Induces Resolution of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Without Fibrosis Worsening. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1147–1159.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staels, B.; Rubenstrunk, A.; Noel, B.; Rigou, G.; Delataille, P.; Millatt, L.J.; Baron, M.; Lucas, A.; Tailleux, A.; Hum, D.W.; et al. Hepatoprotective Effects of the Dual Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha/Delta Agonist, GFT505, in Rodent Models of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease/Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2013, 58, 1941–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schattenberg, J.M.; Pares, A.; Kowdley, K.V.; Heneghan, M.A.; Caldwell, S.; Pratt, D.; Bonder, A.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Levy, C.; Vierling, J.; et al. A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of Elafibranor in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Incomplete Response to UDCA. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 1344–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowdley, K.V.; Bowlus, C.L.; Levy, C.; Akarca, U.S.; Alvares-da-Silva, M.R.; Andreone, P.; Arrese, M.; Corpechot, C.; Francque, S.M.; Heneghan, M.A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Elafibranor in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, H.A. Elafibranor: First Approval. Drugs 2024, 84, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Boudes, P.F.; Swain, M.G.; Bowlus, C.L.; Galambos, M.R.; Bacon, B.R.; Doerffel, Y.; Gitlin, N.; Gordon, S.C.; Odin, J.A.; et al. Seladelpar (MBX-8025), a Selective PPAR-δ Agonist, in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis with an Inadequate Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid: A Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2, Proof-of-Concept Study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlus, C.L.; Galambos, M.R.; Aspinall, R.J.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Jones, D.E.J.; Dörffel, Y.; Gordon, S.C.; Harrison, S.A.; Kremer, A.E.; Mayo, M.J.; et al. A Phase II, Randomized, Open-Label, 52-Week Study of Seladelpar in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfield, G.M.; Shiffman, M.L.; Gulamhusein, A.; Kowdley, K.V.; Vierling, J.M.; Levy, C.; Kremer, A.E.; Zigmond, E.; Andreone, P.; Gordon, S.C.; et al. Seladelpar Efficacy and Safety at 3 Months in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis: ENHANCE, a Phase 3, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Hepatology 2023, 78, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo, M.J.; Vierling, J.M.; Bowlus, C.L.; Levy, C.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Neff, G.W.; Galambos, M.R.; Gordon, S.C.; Borg, B.B.; Harrison, S.A.; et al. Open-Label, Clinical Trial Extension: Two-Year Safety and Efficacy Results of Seladelpar in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, A.P.; Powell, J. Seladelpar for the Treatment of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Ann. Pharmacother. 2025, 59, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.K.; Misra, S. Seladelpar: A Comprehensive Review of Its Clinical Efficacy and Safety in the Treatment of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J. Basic. Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2025, 36, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfield, G.M.; Bowlus, C.L.; Mayo, M.J.; Kremer, A.E.; Vierling, J.M.; Kowdley, K.V.; Levy, C.; Villamil, A.; Ladrón De Guevara Cetina, A.L.; Janczewska, E.; et al. A Phase 3 Trial of Seladelpar in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoy, S.M. Seladelpar: First Approval. Drugs 2024, 84, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsen A Phase III Randomised, Parallel-Group, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Two-Arm Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Elafibranor 80 Mg on Long-Term Clinical Outcomes in Adult Participants with Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC). 2025. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06016842 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Levy, C.; Trivedi, P.J.; Kowdley, K.V.; Gordon, S.C.; Bowlus, C.L.; Londoño, M.C.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Gulamhusein, A.; Lawitz, E.J.; Vierling, J.M.; et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Selective PPARδ Agonist Seladelpar in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: ASSURE Interim Study Results. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric, L.; Palak, J.T.; Kris, V.K.; Stuart, C.G.; Christopher, L.B.; Maria, C.L.; Gideon, H.; Aliya, G.; Vicki, S.; Daria, B.C.; et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Open-Label Seladelpar Treatment in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Pooled Interim Results for Up to 3 Years From the ASSURE Study. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 20, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jani, R.H.; Pai, V.; Jha, P.; Jariwala, G.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Bhansali, A.; Joshi, S. A Multicenter, Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Saroglitazar 2 and 4 Mg Compared with Placebo in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients Having Hypertriglyceridemia Not Controlled with Atorvastatin Therapy (PRESS VI). Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2014, 16, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuppalanchi, R.; Caldwell, S.H.; Pyrsopoulos, N.; deLemos, A.S.; Rossi, S.; Levy, C.; Goldberg, D.S.; Mena, E.A.; Sheikh, A.; Ravinuthala, R.; et al. Proof-of-Concept Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Saroglitazar in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuppalanchi, R.; González-Huezo, M.S.; Payan-Olivas, R.; Muñoz-Espinosa, L.E.; Shaikh, F.; Pio Cruz-Lopez, J.L.; Parmar, D. A Multicenter, Open-Label, Single-Arm Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Saroglitazar in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2021, 12, e00327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuppalanchi, R.; Cruz, M.M.; Momin, T.; Shaikh, F.; Swint, K.; Patel, H.; Parmar, D. Pharmacokinetic, Safety, and Pharmacodynamic Profiles of Saroglitazar Magnesium in Cholestatic Cirrhosis with Hepatic Impairment and Participants with Renal Impairment. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 117, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, L.; Ferrigno, B.; Marenco-Flores, A.; Alsaqa, M.; Rojas, N.; Barba, R.; Goyes, D.; Medina-Morales, E.; Saberi, B.; Patwardhan, V.; et al. Primary Biliary Cholangitis Has the Worst Quality of Life Indicators among the Autoimmune Liver Diseases: A United States Cohort. Ann. Hepatol. 2025, 30, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmi, C.; Gershwin, M.E.; Lindor, K.D.; Worman, H.J.; Gold, E.B.; Watnik, M.; Utts, J.; Invernizzi, P.; Kaplan, M.M.; Vierling, J.M.; et al. Quality of Life and Everyday Activities in Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2007, 46, 1836–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, X.; Yang, X.; Fu, H.-Y.; Xu, J.-M.; Tang, Y.-M. Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaires Used in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Systematic Review. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 57, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Sasaki-Tanaka, R.; Kimura, N.; Abe, H.; Yoshida, T.; Hayashi, K.; Sakamaki, A.; Yokoo, T.; Kamimura, H.; Tsuchiya, A.; et al. Pruritus in Chronic Cholestatic Liver Diseases, Especially in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.T.; de Souza, A.R.; Thompson, A.H.; McLaughlin, M.M.; Dever, J.J.; Myers, J.A.; Chen, J.V. Cholestatic Pruritus Treatments in Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis: A Systematic Literature Review. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 2710–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Düll, M.M.; Kremer, A.E. Evaluation and Management of Pruritus in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Clin. Liver Dis. 2022, 26, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beuers, U.; Wolters, F.; Oude Elferink, R.P.J. Mechanisms of Pruritus in Cholestasis: Understanding and Treating the Itch. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, M.I.; Burt, A.D.; Jones, D.E.J. Hepatitis and Liver Dysfunction with Rifampicin Therapy for Pruritus in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Gut 2002, 50, 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terra, S.G.; Tsunoda, S.M. Opioid Antagonists in the Treatment of Pruritus from Cholestatic Liver Disease. Ann. Pharmacother. 1998, 32, 1228–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrion, A.F.; Rosen, J.D.; Levy, C. Understanding and Treating Pruritus in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Clin. Liver Dis. 2018, 22, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, H.D.; Lizaola, B.; Tapper, E.B.; Bonder, A. Management of Pruritus in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Narrative Review. Am. J. Med. 2017, 130, 744.e1–744.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataei, S.; Kord, L.; Larki, A.; Yasrebifar, F.; Mehrpooya, M.; Seyedtabib, M.; Hasanzarrini, M. Comparison of Sertraline with Rifampin in the Treatment of Cholestatic Pruritus: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Rev. Recent. Clin. Trials 2019, 14, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Pan, J.; Miao, H.; Zhang, H.; Xing, L.; Yu, X. Fibrates for the Treatment of Pruritus in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 7697–7705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, A.E.; Mayo, M.J.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Levy, C.; Bowlus, C.L.; Jones, D.E.; Johnson, J.D.; McWherter, C.A.; Choi, Y.-J. Seladelpar Treatment Reduces IL-31 and Pruritus in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Hepatology 2024, 80, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfield, G.M.; Bowlus, C.L.; Jones, D.E.J.; Kremer, A.E.; Mayo, M.J.; Tanaka, A.; Andreone, P.; Jia, J.; Jin, Q.; Macías-Rodríguez, R.U.; et al. Linerixibat in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Cholestatic Pruritus (GLISTEN): A Randomised, Multicentre, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, S2468-1253(25)00192-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.T.; Das, S.; Fettiplace, J.; von Maltzahn, R.; Troke, P.J.F.; McLaughlin, M.M.; Jones, D.E.; Kremer, A.E. Pervasive Role of Pruritus in Impaired Quality of Life in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Data from the GLIMMER Study. Hepatol. Commun. 2025, 9, e0635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, Y.M.; Izquierdo-Altarejos, P.; Martinez-García, M.; Giménez-Garzó, C.; Mincheva, G.; Doverskog, M.; Jones, D.E.J.; Balzano, T.; Llansola, M.; Felipo, V. Golexanolone Improves Fatigue, Motor Incoordination and Gait and Memory in Rats with Bile Duct Ligation. Liver Int. 2024, 44, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, M.; Mells, G.F.; Pells, G.; Dawwas, M.F.; Newton, J.L.; Heneghan, M.A.; Neuberger, J.M.; Day, D.B.; Ducker, S.J.; The UK PBC Consortium; et al. Sex and Age Are Determinants of the Clinical Phenotype of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis and Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 560–569.e7; quiz e13–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poupon, R.E.; Lindor, K.D.; Cauch-Dudek, K.; Dickson, E.R.; Poupon, R.; Heathcote, E.J. Combined Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials of Ursodeoxycholic Acid in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1997, 113, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, P.; Batts, K.P.; Therneau, T.M.; Jorgensen, R.A.; Dickson, E.R.; Lindor, K.D. Long-Term Ursodeoxycholic Acid Delays Histological Progression in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 1999, 29, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.J.; Lammers, W.J.; van Buuren, H.R.; Parés, A.; Floreani, A.; Janssen, H.L.A.; Invernizzi, P.; Battezzati, P.M.; Ponsioen, C.Y.; Corpechot, C.; et al. Stratification of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: A Multicentre International Study. Gut 2016, 65, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, K.; Hirohara, J.; Ueno, Y.; Nakano, T.; Kakuda, Y.; Tsubouchi, H.; Ichida, T.; Nakanuma, Y. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: National Data from Japan. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1942–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goet, J.C.; Harms, M.H.; Carbone, M.; Hansen, B.E. Risk Stratification and Prognostic Modelling in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2018, 34–35, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lleo, A.; Jepsen, P.; Morenghi, E.; Carbone, M.; Moroni, L.; Battezzati, P.M.; Podda, M.; Mackay, I.R.; Gershwin, M.E.; Invernizzi, P. Evolving Trends in Female to Male Incidence and Male Mortality of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, A.C.; Lammers, W.J.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Invernizzi, P.; Mason, A.L.; Ponsioen, C.Y.; Floreani, A.; Corpechot, C.; Mayo, M.J.; Pares, A.; et al. P1184: Age, Bilirubin and Albumin, Regardless of Sex, Are the Strongest Independent Predictors of Biochemical Response and Transplantation-Free Survival in Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, S798–S799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.J.; Bruns, T.; Cheung, A.; Li, K.-K.; Kittler, C.; Kumagi, T.; Shah, H.; Corbett, C.; Al-Harthy, N.; Acarsu, U.; et al. Optimising Risk Stratification in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: AST/Platelet Ratio Index Predicts Outcome Independent of Ursodeoxycholic Acid Response. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, M.; Nardi, A.; Flack, S.; Carpino, G.; Varvaropoulou, N.; Gavrila, C.; Spicer, A.; Badrock, J.; Bernuzzi, F.; Cardinale, V.; et al. Pretreatment Prediction of Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Development and Validation of the UDCA Response Score. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 3, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, K.; Grambsch, P.M.; Wiesner, R.H.; Lindor, K.D.; Dickson, E.R. Diminished Survival in Asymptomatic Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. A Prospective Study. Gastroenterology 1990, 98, 1567–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.; Chetwynd, A.; Newman, W.; Metcalf, J.V.; James, O.F.W. Survival and Symptom Progression in a Geographically Based Cohort of Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Follow-up for up to 28 Years. Gastroenterology 2002, 123, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, J.V.; Mitchison, H.C.; Palmer, J.M.; Jones, D.E.; Bassendine, M.F.; James, O.F. Natural History of Early Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Lancet 1996, 348, 1399–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, J.; Cauch-Dudek, K.; O’Rourke, K.; Wanless, I.R.; Heathcote, E.J. Asymptomatic Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: A Study of Its Natural History and Prognosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1999, 94, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarneti, C.; Muratori, P.; Lalanne, C.; Fabbri, A.; Menichella, R.; Granito, A.; Masi, C.; Lenzi, M.; Cassani, F.; Pappas, G.; et al. Fatigue and Pruritus at Onset Identify a More Aggressive Subset of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2015, 35, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.E.; Al-Rifai, A.; Frith, J.; Patanwala, I.; Newton, J.L. The Independent Effects of Fatigue and UDCA Therapy on Mortality in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Results of a 9 Year Follow-Up. J. Hepatol. 2010, 53, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, F.; Balducci, D.; Mancinelli, M.; Buzzanca, V.; Fracchia, E.; Tarantino, G.; Benedetti, A.; Marzioni, M.; Maroni, L. Risk Stratification in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cançado, G.G.L.; Fucuta, P.D.S.; Gomes, N.M.D.F.; Couto, C.A.; Cançado, E.L.R.; Terrabuio, D.R.B.; Villela-Nogueira, C.A.; Braga, M.H.; Nardelli, M.J.; Faria, L.C.; et al. Alkaline Phosphatase and Liver Fibrosis at Diagnosis Are Associated with Deep Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2024, 48, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammers, W.J.; van Buuren, H.R.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Janssen, H.L.A.; Invernizzi, P.; Mason, A.L.; Ponsioen, C.Y.; Floreani, A.; Corpechot, C.; Mayo, M.J.; et al. Levels of Alkaline Phosphatase and Bilirubin Are Surrogate End Points of Outcomes of Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: An International Follow-up Study. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 1338–1349.e5; quiz e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpechot, C.; Lemoinne, S.; Soret, P.-A.; Hansen, B.; Hirschfield, G.; Gulamhusein, A.; Montano-Loza, A.J.; Lytvyak, E.; Pares, A.; Olivas, I.; et al. Adequate versus Deep Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: To What Extent and under What Conditions Is Normal Alkaline Phosphatase Level Associated with Complication-Free Survival Gain? Hepatology 2024, 79, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo Perez, C.F.; Ioannou, S.; Hassanally, I.; Trivedi, P.J.; Corpechot, C.; van der Meer, A.J.; Lammers, W.J.; Battezzati, P.M.; Lindor, K.D.; Nevens, F.; et al. Optimizing Therapy in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Alkaline Phosphatase at Six Months Identifies One-Year Non-Responders and Predicts Survival. Liver Int. 2023, 43, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.M.; Smith, H.; Schaffner, F. Serum Bilirubin: A Prognostic Factor in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Gut 1979, 20, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaravaglio, M.; Carbone, M. Prognostic Scoring Systems in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Clin. Liver Dis. 2022, 26, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, I. Elevation of Serum Gamma-Glutamyl Transpeptidase Precedes That of Alkaline Phosphatase in the Early Stages of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatol. Res. 1999, 14, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azemoto, N.; Kumagi, T.; Abe, M.; Konishi, I.; Matsuura, B.; Hiasa, Y.; Onji, M. Biochemical Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid Predicts Long-Term Outcome in Japanese Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatol. Res. 2011, 41, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ter Borg, P.C.J.; Schalm, S.W.; Hansen, B.E.; van Buuren, H.R.; Dutch PBC Study Group. Prognosis of Ursodeoxycholic Acid-Treated Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Results of a 10-Yr Cohort Study Involving 297 Patients. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 2044–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvaruso, V.; Celsa, C.; Cristoferi, L.; Scaravaglio, M.; Smith, R.; Kaur, S.; Di Maria, G.; Capodicasa, L.; Pennisi, G.; Gerussi, A.; et al. Noninvasive Assessment of Portal Hypertension in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis Is Affected by Severity of Cholestasis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 23, 1766–1775.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Kondo, H.; Tanaka, A.; Komori, A.; Ito, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Ohira, H.; Zeniya, M.; Hashimoto, E.; Honda, M.; et al. Autoantibody Status and Histological Variables Influence Biochemical Response to Treatment and Long-Term Outcomes in Japanese Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatol. Res. 2015, 45, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Ran, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, B.; Zhou, L. Anti-Gp210-Positive Primary Biliary Cholangitis: The Dilemma of Clinical Treatment and Emerging Mechanisms. Ann. Hepatol. 2023, 28, 101121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Han, W.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Duan, Z. Early Prognostic Utility of Gp210 Antibody-Positive Rate in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Meta-Analysis. Dis. Markers 2019, 2019, 9121207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, D.; Janmohamed, A.; Plant, T.; Davidson, M.; Norman, H.; Russell, E.; Serevina, O.; Chung, K.; Qamar, K.; Gunson, B.; et al. Antibodies to Gp210 and Understanding Risk in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Liver Int. 2021, 40, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Kondo, H.; Mori, T.; Komori, A.; Matsuyama, M.; Ito, M.; Takii, Y.; Koyabu, M.; Yokoyama, T.; Migita, K.; et al. Anti-Gp210 and Anti-Centromere Antibodies Are Different Risk Factors for the Progression of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2007, 45, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratori, P.; Muratori, L.; Ferrari, R.; Cassani, F.; Bianchi, G.; Lenzi, M.; Rodrigo, L.; Linares, A.; Fuentes, D.; Bianchi, F.B. Characterization and Clinical Impact of Antinuclear Antibodies in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 98, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.-D.; Yao, T.-T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G.-Q. Treatment of Primary Biliary Cholangitis with Ursodeoxycholic Acid, Prednisolone and Immunosuppressants in Patients Not Responding to Ursodeoxycholic Acid Alone and the Prognostic Indicators. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2020, 44, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Miao, Q.; Xiao, X.; Wei, Y.; Bian, Z.; Sheng, L.; Chen, X.; et al. The Risk Predictive Values of UK-PBC and GLOBE Scoring System in Chinese Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis: The Additional Effect of Anti-Gp210. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M. Clinical Significance of Autoantibodies in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Semin. Liver Dis. 2014, 34, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, S.; Ichida, T.; Yoshida, T.; Hayakawa, A.; Uchida, M.; Tashiro-Itoh, T.; Matsuda, Y.; Ishihara, K.; Asakura, H. Autoantibodies against a 210 kDa Glycoprotein of the Nuclear Pore Complex as a Prognostic Marker in Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1998, 13, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatselis, N.K.; Zachou, K.; Norman, G.L.; Gabeta, S.; Papamichalis, P.; Koukoulis, G.K.; Dalekos, G.N. Clinical Significance of the Fluctuation of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis-Related Autoantibodies during the Course of the Disease. Autoimmunity 2013, 46, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reig, A.; Norman, G.L.; Garcia, M.; Shums, Z.; Ruiz-Gaspà, S.; Bentow, C.; Mahler, M.; Romera, M.A.; Vinas, O.; Pares, A. Novel Anti-Hexokinase 1 Antibodies Are Associated with Poor Prognosis in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 1634–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tana, M.M.; Shums, Z.; Milo, J.; Norman, G.L.; Leung, P.S.; Gershwin, M.E.; Noureddin, M.; Kleiner, D.E.; Zhao, X.; Heller, T.; et al. The Significance of Autoantibody Changes Over Time in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2015, 144, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Tian, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, F. The Value of Antinuclear Antibodies in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Clin. Exp. Med. 2008, 8, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Jia, G.; Cui, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, R.; Deng, J.; Guo, G.; Shang, Y.; Han, Y. The Prognostic Value of Anti-Gp210 and Anti-Centromere Antibodies in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Enhancing the Prognostic Utility on the GLOBE Scoring System. Dig. Liver Dis. 2025, 57, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G.L.; Yang, C.-Y.; Ostendorff, H.P.; Shums, Z.; Lim, M.J.; Wang, J.; Awad, A.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Milkiewicz, P.; Bloch, D.B.; et al. Anti-Kelch-like 12 and Anti-Hexokinase 1: Novel Autoantibodies in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2015, 35, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, M.H.; Lammers, W.J.; Thorburn, D.; Corpechot, C.; Invernizzi, P.; Janssen, H.L.A.; Battezzati, P.M.; Nevens, F.; Lindor, K.D.; Floreani, A.; et al. Major Hepatic Complications in Ursodeoxycholic Acid-Treated Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Risk Factors and Time Trends in Incidence and Outcome. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolis, F.; Cazzaniga, G.; Pagni, F.; Invernizzi, P.; Carbone, M.; Gerussi, A. The Phenotypic Landscape of Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Autoimmune Hepatitis Variants. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 48, 502225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammers, W.J.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Corpechot, C.; Nevens, F.; Lindor, K.D.; Janssen, H.L.A.; Floreani, A.; Ponsioen, C.Y.; Mayo, M.J.; Invernizzi, P.; et al. Development and Validation of a Scoring System to Predict Outcomes of Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Receiving Ursodeoxycholic Acid Therapy. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 1804–1812.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montano-Loza, A.J.; Hansen, B.E.; Corpechot, C.; Roccarina, D.; Thorburn, D.; Trivedi, P.; Hirschfield, G.; McDowell, P.; Poupon, R.; Dumortier, J.; et al. Factors Associated with Recurrence of Primary Biliary Cholangitis After Liver Transplantation and Effects on Graft and Patient Survival. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 96–107.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, K.; Nakanuma, Y. Biliary Innate Immunity and Cholangiopathy. Hepatol. Res. 2007, 37 (Suppl. S3), S430–S437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, J.; Dickson, E.R.; McDonald, G.S. Staging of Chronic Nonsuppurative Destructive Cholangitis (Syndrome of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis). Virchows Arch. A Pathol. Anat. Histol. 1978, 379, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheuer, P. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1967, 60, 1257–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, K.; Hsu, M.; Ikeda, H.; Zeniya, M.; Nakanuma, Y. Application and Validation of a New Histologic Staging and Grading System for Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 47, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendum, D.; Boëlle, P.-Y.; Bedossa, P.; Zafrani, E.-S.; Charlotte, F.; Saint-Paul, M.-C.; Michalak, S.; Chazouillères, O.; Corpechot, C. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Proposal for a New Simple Histological Scoring System. Liver Int. 2015, 35, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, A.; Engström-Laurent, A.; Lööf, L. Serum Hyaluronate in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis—A Biochemical Marker for Progressive Liver Damage. Hepatology 1988, 8, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, M.J.; Parkes, J.; Adams-Huet, B.; Combes, B.; Mills, A.S.; Markin, R.S.; Rubin, R.; Wheeler, D.; Contos, M.; West, A.B.; et al. Prediction of Clinical Outcomes in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis by Serum Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Assay. Hepatology 2008, 48, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinaga, Y.; Namisaki, T.; Takaya, H.; Tsuji, Y.; Suzuki, J.; Shibamoto, A.; Kubo, T.; Iwai, S.; Tomooka, F.; Takeda, S.; et al. Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Score as a Surrogate of Liver-Related Complications and Mortality in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Medicine 2021, 100, e27403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huet, P.-M.; Vincent, C.; Deslaurier, J.; Coté, J.; Matsutami, S.; Boileau, R.; Huet-van Kerckvoorde, J. Portal Hypertension and Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Effect of Long-Term Ursodeoxycholic Acid Treatment. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 1552–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, X.; Wu, R.; Niu, J. Increased Red Cell Width Distribution to Lymphocyte Ratio Is a Predictor of Histologic Severity in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Medicine 2018, 97, e13431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, Y.; Su, Z.; Yang, F.; Lv, H.; Lin, L.; Sun, C. Red Blood Cell Distribution Width to Platelet Ratio Levels in Assessment of Histologic Severity in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2018, 78, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallio, M.; Romeo, M.; Vaia, P.; Auletta, S.; Mammone, S.; Cipullo, M.; Sapio, L.; Ragone, A.; Niosi, M.; Naviglio, S.; et al. Red Cell Distribution Width/Platelet Ratio Estimates the 3-Year Risk of Decompensation in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease-Induced Cirrhosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmez, S.; Sayar, S.; Avcioglu, U.; Tenlik, İ.; Ozaslan, E.; Koseoglu, H.T.; Altiparmak, E. The Relationship between Liver Histology and Noninvasive Markers in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 28, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, R.; Gao, X.; Jin, Q.; Niu, J. Red Blood Cell Distribution Width to Platelet Ratio Is Related to Histologic Severity of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Medicine 2016, 95, e3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stasi, C.; Leoncini, L.; Biagini, M.R.; Arena, U.; Madiai, S.; Laffi, G.; Marra, F.; Milani, S. Assessment of Liver Fibrosis in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Comparison between Indirect Serum Markers and Fibrosis Morphometry. Dig. Liver Dis. 2016, 48, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahtaci, M.; Yurekli, O.T.; Bolat, A.D.; Balci, S.; Akin, F.E.; Buyukasik, N.S.; Ersoy, O. Increased Mean Platelet Volume Is Related to Histologic Severity of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 27, 1382–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Xu, H.; Qu, L.; Zhang, D.; Gao, P. Platelet Count to Spleen Thickness Ratio Is Related to Histologic Severity of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Medicine 2018, 97, e9843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Franchis, R.; Bosch, J.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Reiberger, T.; Ripoll, C.; Baveno VII Faculty. Baveno VII—Renewing Consensus in Portal Hypertension. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Enomoto, H.; Iwata, Y.; Hasegawa, K.; Nakano, C.; Takata, R.; Nishimura, T.; Yoh, K.; Aizawa, N.; Sakai, Y.; et al. Impact of Serum Wisteria Floribunda Agglutinin Positive Mac-2-Binding Protein and Serum Interferon-γ-Inducible Protein-10 in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Hepatol. Res. 2016, 46, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corpechot, C.; Carrat, F.; Gaouar, F.; Chau, F.; Hirschfield, G.; Gulamhusein, A.; Montano-Loza, A.J.; Lytvyak, E.; Schramm, C.; Pares, A.; et al. Liver Stiffness Measurement by Vibration-Controlled Transient Elastography Improves Outcome Prediction in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, Y.; Hirooka, M.; Abe, M.; Tokumoto, Y.; Yoshida, O.; Watanabe, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Imai, Y.; Yukimoto, A.; Kumagi, T.; et al. Comparison between Real-Time Tissue Elastography and Vibration-Controlled Transient Elastography for the Assessment of Liver Fibrosis and Disease Progression in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Hepatol. Res. 2017, 47, 1252–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on Non-Invasive Tests for Evaluation of Liver Disease Severity and Prognosis—2021 Update. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 659–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.; Soret, P.-A.; Lemoinne, S.; Hansen, B.; Hirschfield, G.; Gulamhusein, A.; Montano-Loza, A.J.; Lytvyak, E.; Parés, A.; Olivas, I.; et al. Dynamics of Liver Stiffness Measurement and Clinical Course of Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 2432–2441.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti, C.; Cittone, M.G.; Manfredi, G.F.; De Benedittis, C.; Paggi, N.; Baorda, F.; Di Benedetto, D.; Minisini, R.; Pirisi, M. Spleen Stiffness Measurement Predicts Decompensation and Rules out High-Risk Oesophageal Varices in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. JHEP Rep. 2024, 6, 100952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, S.K.; Yin, M.; Ehman, R.L. Magnetic Resonance Elastography of Liver: Technique, Analysis, and Clinical Applications. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2013, 37, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, S.; Motosugi, U.; Morisaka, H.; Sano, K.; Ichikawa, T.; Tatsumi, A.; Enomoto, N.; Matsuda, M.; Fujii, H.; Onishi, H. Comparison of the Diagnostic Accuracies of Magnetic Resonance Elastography and Transient Elastography for Hepatic Fibrosis. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015, 33, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Venkatesh, S.K.; Wang, Z.; Miller, F.H.; Motosugi, U.; Low, R.N.; Hassanein, T.; Asbach, P.; Godfrey, E.M.; Yin, M.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of Magnetic Resonance Elastography in Staging Liver Fibrosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 13, 440–451.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.R.; Wiesner, R.H.; Poterucha, J.J.; Therneau, T.M.; Benson, J.T.; Krom, R.A.; Dickson, E.R. Adaptation of the Mayo Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Natural History Model for Application in Liver Transplant Candidates. Liver Transpl. 2000, 6, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, E.R.; Grambsch, P.M.; Fleming, T.R.; Fisher, L.D.; Langworthy, A. Prognosis in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Model for Decision Making. Hepatology 1989, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaugh, P.A.; Dickson, E.R.; Van Dam, G.M.; Malinchoc, M.; Grambsch, P.M.; Langworthy, A.L.; Gips, C.H. Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Prediction of Short-Term Survival Based on Repeated Patient Visits. Hepatology 1994, 20, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll, J.; Boyer, J.L.; Barry, D.; Klatskin, G. The Prognostic Importance of Clinical and Histologic Features in Asymptomatic and Symptomatic Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983, 308, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, E.; Neuberger, J.; Crowe, J.; Altman, D.G.; Popper, H.; Portmann, B.; Doniach, D.; Ranek, L.; Tygstrup, N.; Williams, R. Beneficial Effect of Azathioprine and Prediction of Prognosis in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Final Results of an International Trial. Gastroenterology 1985, 89, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, P.J.; Berhane, S.; Kagebayashi, C.; Satomura, S.; Teng, M.; Reeves, H.L.; O’Beirne, J.; Fox, R.; Skowronska, A.; Palmer, D.; et al. Assessment of Liver Function in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A New Evidence-Based Approach-the ALBI Grade. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.W.H.; Chan, R.C.K.; Wong, G.L.H.; Wong, V.W.S.; Choi, P.C.L.; Chan, H.L.Y.; To, K.-F. New Simple Prognostic Score for Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Albumin-Bilirubin Score. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 30, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinchoc, M.; Kamath, P.S.; Gordon, F.D.; Peine, C.J.; Rank, J.; ter Borg, P.C. A Model to Predict Poor Survival in Patients Undergoing Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunts. Hepatology 2000, 31, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parés, A.; Caballería, L.; Rodés, J. Excellent Long-Term Survival in Patients with Primary Biliary Cirrhosis and Biochemical Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagi, T.; Guindi, M.; Fischer, S.E.; Arenovich, T.; Abdalian, R.; Coltescu, C.; Heathcote, E.J.; Hirschfield, G.M. Baseline Ductopenia and Treatment Response Predict Long-Term Histological Progression in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 2186–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-N.; Shi, T.-Y.; Shi, X.-H.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.-J.; Liu, B.; Gao, L.-X.; Shuai, Z.-W.; Kong, F.; Chen, H.; et al. Early Biochemical Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid and Long-Term Prognosis of Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Results of a 14-Year Cohort Study. Hepatology 2013, 58, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpechot, C.; Chazouillères, O.; Poupon, R. Early Primary Biliary Cirrhosis: Biochemical Response to Treatment and Prediction of Long-Term Outcome. J. Hepatol. 2011, 55, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, E.; Hernández, L.; Miquel, M.; Sánchez-Delgado, J.; Dalmau, B.; Valero, O.; Vergara, M.; Casas, M. Analysis of Predictive Response Scores to Treatment with Ursodeoxycholic Acid in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Med. Clin. 2019, 152, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazda, J.; Drazilova, S.; Gazda, M.; Janicko, M.; Koky, T.; Macej, M.; Carbone, M.; Jarcuska, P. Treatment Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2023, 55, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, M.; Sharp, S.J.; Flack, S.; Paximadas, D.; Spiess, K.; Adgey, C.; Griffiths, L.; Lim, R.; Trembling, P.; Williamson, K.; et al. The UK-PBC Risk Scores: Derivation and Validation of a Scoring System for Long-Term Prediction of End-Stage Liver Disease in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Hepatology 2016, 63, 930–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristoferi, L.; Calvaruso, V.; Overi, D.; Viganò, M.; Rigamonti, C.; Degasperi, E.; Cardinale, V.; Labanca, S.; Zucchini, N.; Fichera, A.; et al. Accuracy of Transient Elastography in Assessing Fibrosis at Diagnosis in Naïve Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Dual Cut-Off Approach. Hepatology 2021, 74, 1496–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerussi, A.; Verda, D.; Bernasconi, D.P.; Carbone, M.; Komori, A.; Abe, M.; Inao, M.; Namisaki, T.; Mochida, S.; Yoshiji, H.; et al. Machine Learning in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Novel Approach for Risk Stratification. Liver Int. 2022, 42, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Wei, Y.; Xiong, A.; Li, Y.; Guan, H.; Wang, Q.; Miao, Q.; Bian, Z.; Xiao, X.; Lian, M.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Serum and Fecal Bile Acid Profiles and Interaction with Gut Microbiota in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 58, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Chu, H. Targeting Gut Microbiota for the Treatment of Primary Biliary Cholangitis: From Bench to Bedside. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2023, 11, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammert, C.; Shin, A.S.; Xu, H.; Hemmerich, C.; O’Connell, T.M.; Chalasani, N. Short-Chain Fatty Acid and Fecal Microbiota Profiles Are Linked to Fibrosis in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2021, 368, fnab038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, M.; Dallio, M.; Di Nardo, F.; Napolitano, C.; Vaia, P.; Martinelli, G.; Federico, P.; Olivieri, S.; Iodice, P.; Federico, A. The Role of the Gut-Biliary-Liver Axis in Primary Hepatobiliary Liver Cancers: From Molecular Insights to Clinical Applications. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.-J.; Ying, G.-X.; Dong, S.-L.; Xiang, B.; Jin, Q.-F. Gut Microbial Profile of Treatment-Naive Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1126117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Tang, X.; Qiao, W.; Sun, L.; Shi, H.; Chen, D.; Xu, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Huang, C.; et al. Machine Learning-Based Characterization of the Gut Microbiome Associated with the Progression of Primary Biliary Cholangitis to Cirrhosis. Microbes Infect. 2024, 26, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qian, Q.; Chen, R.; et al. Gut Microbiome Pattern Impacts Treatment Response in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Med 2025, 6, 100504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Song, T.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, B.; Huang, C. Distinct Signatures of Gut Microbiota and Metabolites in Primary Biliary Cholangitis with Poor Biochemical Response after Ursodeoxycholic Acid Treatment. Cell Biosci. 2024, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, W.; Wu, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J.; You, L.; Li, H.; Zheng, C.; Gao, Y.; Sun, X. Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization Links Gut Microbiota to Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallio, M.; Romeo, M.; Cipullo, M.; Ventriglia, L.; Scognamiglio, F.; Vaia, P.; Iadanza, G.; Coppola, A.; Federico, A. Systemic Oxidative Balance Reflects the Liver Disease Progression Status for Primary Biliary Cholangitis (Pbc): The Narcissus Fountain. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Lee, K.J.; Park, S.W.; Koh, D.H.; Lee, J. Point-of-Care Testing and Biomarkers in Biliary Diseases: Current Evidence and Future Directions. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, S.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, K.; Guo, G.; Li, B.; Shang, Y.; Han, Y. Integrative Bioinformatics Analysis and Experimental Validation of Key Biomarkers for Risk Stratification in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2023, 25, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowdley, K.V.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Jones, D.E. The Evolving Use of Biochemical Markers in the Management of Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Discussion. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 17, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Jiang, S.; Fan, Q.; Wen, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K.; Yang, H.; Guo, C.; Zhou, X.; Guo, G.; et al. Prevalence and Effect on Prognosis of Sarcopenia in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1346165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhong, J.; Liu, X.; Feng, J.; Jin, Q.; Ren, W.; Wang, J.; Ma, D.; Rao, H.; et al. Mean Liver Density Independently Predicts Therapeutic Response and Liver-Related Mortality in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2024, 14, 9074–9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug/Agent | Target/Class | Mechanism of Action | Key Trials/Evidence | Clinical Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UDCA | Hydrophilic bile acid | Replaces toxic bile acids; anti-cholestatic, cytoprotective, immunomodulatory | Multiple RCTs; Global PBC Study Group (n = 3902): ↑ transplant-free survival | First-line standard of care |

| Budesonide | Corticosteroid | Anti-inflammatory; high hepatic first-pass metabolism | RCTs: improved biochemistry; no histological benefit; contraindicated in cirrhosis | Off-label; limited to non-cirrhotic overlap |

| OCA | FXR agonist | Suppresses bile acid synthesis; ↑ bile flow | POISE (NCT03505723): ↑ biochemical response; COBALT (NCT02308111): failed on hard endpoints; EMA withdrawal (2024) | Withdrawn in EU; restricted in US |

| Bezafibrate | Pan-PPAR agonist (α, β/δ, γ) | ↓ bile acid synthesis; anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic | BEZURSO (NCT01654731): 67% ALP normalization; real-world data: ↓ mortality/transplant risk | Off-label; not approved for PBC |

| Fenofibrate | PPAR-α agonist | ↓ CYP7A1 activity; ↑ bile acid detoxification; anti-inflammatory | Open-label studies: biochemical improvement; safety concerns in advanced disease | Off-label; (cautions in decompensated PBC) |

| Elafibranor | Dual PPAR-α/δ agonist | Anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic; modulates bile acid metabolism | ELATIVE (Phase III) (NCT04526665): 51% composite response; FDA accelerated approval (2024) | Approved (US); second-line |

| Seladelpar | Selective PPAR-δ agonist | Anti-inflammatory; choleretic; ↓ IL-31 (pruritus mediator) | RESPONSE (Phase III) (NCT04620733): 62% response; ↓ pruritus; FDA accelerated approval (2024) | Approved (US); second-line |

| Saroglitazar | Dual PPAR-α/γ agonist | ↓ bile acid synthesis; lipid modulation | Phase II/III: ~50% ALP reduction; safety concerns (ALT ↑); ongoing trials | Investigational |

| Linerixibat | IBAT inhibitor | Blocks ileal bile acid reabsorption; ↓ pruritus | GLISTEN (NCT04950127) & GLIMMER (NCT04603937) (Phase III): ↓ WI-NRS, improved sleep and QoL | Investigational |

| Golexanolone | GABA-A R modulator | Neurosteroid; targets central fatigue pathways | Phase 1b/2: under evaluation for fatigue in PBC | Investigational |

| Model | Type | Assessment Timepoint | Key Variables | Primary Endpoint | Performance/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paris I | Binary | 12 months | ALP < 3 × ULN, AST < 2 × ULN, bilirubin < 1 mg/dL | Transplant-free survival | AUROC 0.81–0.82; HR for LREs: 4.22 |

| Paris II | Binary | 12 months | ALP ≤ 1.5 × ULN, AST ≤ 1.5 × ULN, normal bilirubin | LREs | HR for LREs: 4.47 |

| Barcelona | Binary | 12 months | ALP decrease > 40% or normalization | LREs | HR: 1.95 |

| Rotterdam | Binary | 12 months | Albumin, bilirubin | LT or death; LREs | HR: 4.16 (LT/death); 2.98 (LREs) |

| Toronto | Binary | 24 months | ALP < 1.67 × ULN | Histologic progression | HR for LREs: 3.13 |

| Early ALP (6 months) | Binary | 6 months | ALP > 1.9 × ULN | Predicts POISE-defined non-response at 1 year | Identifies ~67% of non-responders early |

| GLOBE Score | Continuous | 12 months | Age, ALP, bilirubin, albumin, platelets | LT-free survival (3–15 years) | AUROC: 0.83–0.94; HR for LREs: 3.03–5.05 |

| UK-PBC Score | Continuous | 12 months | ALP, bilirubin, transaminases, albumin, platelets | LT or liver-related death (5–15 years) | AUROC: 0.79–0.95; HR for LREs: 3.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romeo, M.; Di Nardo, F.; Basile, C.; Napolitano, C.; Vaia, P.; Martinelli, G.; Gregorio, A.D.; Puorto, L.D.; Indipendente, M.; Dallio, M.; et al. The Personalized Management of Primary Biliary Cholangitis in the Era of Precision Medicine: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120597

Romeo M, Di Nardo F, Basile C, Napolitano C, Vaia P, Martinelli G, Gregorio AD, Puorto LD, Indipendente M, Dallio M, et al. The Personalized Management of Primary Biliary Cholangitis in the Era of Precision Medicine: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(12):597. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120597

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomeo, Mario, Fiammetta Di Nardo, Claudio Basile, Carmine Napolitano, Paolo Vaia, Giuseppina Martinelli, Alessia De Gregorio, Luigi Di Puorto, Mattia Indipendente, Marcello Dallio, and et al. 2025. "The Personalized Management of Primary Biliary Cholangitis in the Era of Precision Medicine: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 12: 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120597

APA StyleRomeo, M., Di Nardo, F., Basile, C., Napolitano, C., Vaia, P., Martinelli, G., Gregorio, A. D., Puorto, L. D., Indipendente, M., Dallio, M., & Federico, A. (2025). The Personalized Management of Primary Biliary Cholangitis in the Era of Precision Medicine: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(12), 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15120597