Abstract

Background/Objectives: Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a part of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and it is characterized by colonic-mucosal chronic inflammation with intermittent clinical activity. Personalized medicine is becoming more and more a relevant method of approach in this field, and the identification of potential concerns in a single patient may contribute to the improvement of the clinical approach. Mesalamine represents the cornerstone of therapy for mild–moderate disease forms, but non-adherence to medical therapy represents a critical health problem, although it is underestimated by many physicians, with evident consequences in terms of disease-related complications. The aim of the present study is to evaluate the magnitude of non-adherence to oral mesalamine in UC patients performing a systematic review and meta-analysis of literature. Methods: A literature search in PubMed and Cochrane databases was performed for studies reporting the non-adherence rate to oral mesalamine in adult UC patients, and eligible studies have been selected for evaluation. The type of study (trial vs. observational), geographic area, sample size, method of adherence assessment, and non-adherence rate were considered. Results: From a total of 464 articles, 34 studies were included in the meta-analysis after selection. Sixteen studies (47%) are observational, and eighteen (53%) are clinical trials. A total of 12/34 (35%) studies are from North America, 14/34 (41%) from Europe, 4/34 (12%) from Asia, with 4/34 (12%) from mixed areas of the world. The mean non-adherence rate was 32%, but with a consistent variability among the studies. In particular, the non-adherence rate was significantly higher in observational studies vs. clinical trials (47 vs. 20%, p < 0.001), and in North American vs. European and Asian studies (54 vs. 23 vs. 4%, respectively, p < 0.001). Conclusions: The non-adherence rate to oral mesalamine is variably reported in the literature due to the inhomogeneity of available studies, but it represents a consistent problem, often neglected, that deserves future research. A personalized approach by a physician to a single patient can improve the effectiveness of medical therapy and the management of UC patients.

1. Introduction

Medication adherence is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “the extent to which a person’s behavior corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider” [1]. Despite significant research efforts and interventions across many therapeutic areas, non-adherence to medical therapy remains a critical health problem, particularly in patients with chronic diseases [2]. Globally, this phenomenon affects around 50% of patients, with evident consequences in terms of disease-related complications, impaired quality of life, and increased healthcare resource utilization [3]. Non-adherence has been linked to higher rates of hospitalizations, disease relapses, and more aggressive therapeutic interventions, factors that negatively impact both patient outcomes and overall healthcare costs [4].

The causes of non-adherence are multifactorial, encompassing patient-related, treatment-related, and healthcare system-related factors [5]. Patient-related factors include forgetfulness, a lack of understanding of the importance of long-term therapy, concerns about side effects, and the erroneous belief that feeling well during remission justifies stopping treatment. On the treatment side, factors such as the complexity of dosing regimens, the frequency of administration, and the cost of medication may hinder adherence. Finally, system-related barriers include limited access to care, inadequate follow-up, and insufficient support from healthcare providers [1].

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of the main conditions classified under inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), a group of disorders characterized by a dysregulated, immune-driven inflammatory response, primarily affecting the intestine [6]. UC displays an intermittent and relapsing clinical course, with periods of active disease followed by remission, although its exact etiology remains unknown. The hallmark of UC is superficial mucosal inflammation, which starts in the rectum and may extend proximally to the colon [7]. During the active phase, symptoms include diarrhea, bloody stools, urgency, and tenesmus. The primary therapeutic goal is to induce and maintain clinical and endoscopic remission, control the disease, preserve the patient’s quality of life, and prevent complications and ultimately disability [8].

Management strategies for IBD patients are evolving in a double and parallel direction. On the one hand, the standardization of diagnostic and medical procedures, with development and continuous updating of guidelines, aims to guarantee the standard of care for IBD patients in virtually every medical center [9]. On the other hand, the personalized medicine approach, with the holistic consideration of the patient behind the clinical and/or molecular characteristic of the disease, encompassing his/her personal and psychological sphere, is becoming more and more relevant for a truly effective management of such patients [10].

Among the therapeutic options available, mesalamine (5-aminosalicylic acid, 5-ASA) is considered the first-line treatment for both active mild–moderate UC and remission maintenance [11]. Its favorable safety profile and efficacy make it the cornerstone of UC management. Numerous studies and meta-analyses confirm that regular use of mesalamine not only reduces disease symptoms but also delays or prevents the need for therapeutic escalation, such as corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, or biologics [12].

However, as with other chronic therapies, non-adherence to mesalamine poses a major challenge in the long-term management of UC. Non-adherence can significantly compromise the effectiveness of treatment, leading to increased risks of relapse, hospitalization, and complications. In particular, patients who do not adhere to their mesalamine regimen are at a higher risk of disease progression, often requiring more invasive and costly interventions [13]. Previous studies have shown that non-adherence is associated with a substantially higher risk of relapse—up to five times more than in adherent patients [14].

Despite the importance of adherence in managing UC, there are currently no specific guidelines to identify, address, or correct non-adherence in these patients. The lack of clear recommendations is likely due to the variability in findings from studies conducted to date. Some studies report relatively low rates of non-adherence, while others suggest that more than 50% of patients may not adhere to their prescribed therapy [15]. This discrepancy makes it difficult to understand the true scope of the problem and to develop targeted intervention strategies.

Thus, the aim of the present study is to conduct a systematic review of the available literature on non-adherence rates to oral mesalamine in UC patients. The review will be followed by a meta-analysis of the evidence, with the goal of providing a more accurate estimate of the extent of the problem and identifying the main factors associated with the non-adherence rate in the studies. This could provide valuable insights to more accurately identify the magnitude of the problem in order to improve the clinical management of UC patients and optimize the effectiveness of mesalamine therapy, with the final goal to implement the concept of tailoring the therapy for individual patients.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted according to the PRISMA statement [16], and the protocol was registered on the PROSPERO website (CRD42024625400). We conducted a literature search for published literature reporting the adherence rate in adult UC patients for oral mesalamine. Three independent researchers conducted a search in the PubMed and Cochrane database with the following strategy: (mesalamine OR mesalamine OR 5ASA) AND (adherence OR compliance). Both clinical trials and observational retrospective studies were considered. The search was not limited to papers in English. Researchers made a final list of eligible papers, progressively excluding citations based on the title, abstract, and full-text reading. Potential disagreements among researchers were resolved by discussion and voting. To be included in the list of examined paper the following criteria had to be fulfilled: the paper has to be published in full text, while abstracts and conference proceedings were excluded; the study should consider only adult patients with UC, while papers also analyzing Crohn’s disease patients or pediatric IBD patients were excluded; the adherence rate should be clearly expressed, and in the case of comparisons between two groups’ adherence (i.e., single vs. multiple mesalamine dose) the mean adherence rate was calculated; studies considering particular sub-groups of patients (i.e., pregnant UC women) were excluded; duplicates or redundant papers were excluded.

For studies comparing adherence in multiple groups (i.e., mesalamine single vs. multiple dose) we calculated the mean of the reported non-adherence rate. For studies reporting the non-adherence rate at different time-points, we considered only the adherence rate of the longest follow-up reported. In case of studies reporting similar cases, we considered only the one with the higher sample size.

For every included study, the type of study (trial vs. observational), geographic area, sample size, method of adherence assessment, and the non-adherence rate were considered. The non-adherence rates were expressed as the percent (%) of considered patients ± standard deviation (SD). We first calculated the total mean of the non-adherence rate of all the studies included in the analysis. Then, a comparison between the different non-adherence rate in studies with the aforementioned characteristics (different kind of study, geographic area, sample size, and method of adherence assessment) was calculated by t-test, for the comparison of quantitative parameters between two independent groups. Uni- and multivariate analysis was performed considering the independent variables of high (>50%) and low (<10%) non-adherence rate, and the different study characteristics were considered as binomial dependent variables (trials vs. observational studies, monocentric vs. multicentric, European vs. rest of the world studies, North American vs. rest of the world studies, Asian vs. rest of the world studies, studies with sample size >1000 vs. <1000 subjects, and studies that used questionnaires vs. count of prescription/tablets/refills). Variables that produced a significant result in the univariate analysis were analyzed in the multivariate model. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. Med Calc software (version 12.5) was used for statistical calculation.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

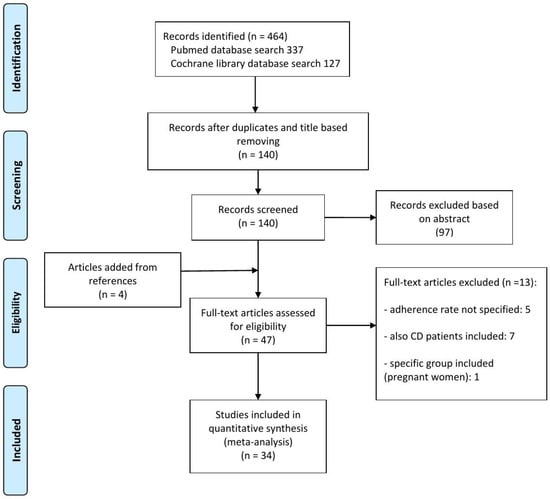

From an initial result of 464 articles, 324 articles were excluded by only removing duplicates and reading the title, and a further 97 after reading the abstract. Finally, after full text examination, 34 articles were included in the meta-analysis [6,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] (Figure 1). Regarding study type, 16 studies (47%) are observational, and 18 (53%) are clinical trials. Among the latter, adherence is considered as the primary endpoint in six studies (33%), the non-primary endpoint in three studies (17%), and in nine studies (50%) it is not considered as the endpoint. Considering geographic area, 12/34 (35%) studies are from North America, 14/34 (41%) are from Europe, 4/34 (12%) are from Asia, and 4/34 (12%) are from mixed areas worldwide. Most of the studies are multicentric (24/34, 71%), while consistent variation is observed regarding the method of assessment of adherence: by questionnaire or diary (8/34, 23.5%); by count of prescription/tablets/refills (17/34, 50%); by urinary drug excretion measurements (1/34, 3%); or by multiple methods or not specified (8/34, 23.5%). Characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of evidence search and selection for the non-adherence rate for oral mesalamine in adult UC patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 34 studies included in the meta-analysis.

3.2. Non-Adherence Rate

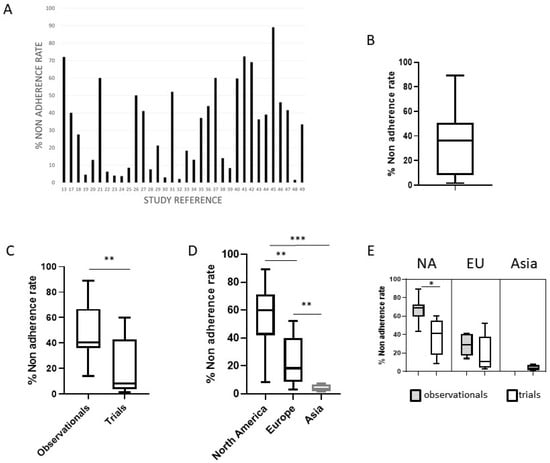

The total mean non-adherence rate was 32.3 ± 24.8%, but consistent variability was observed among the studies (Figure 2A,B). In particular, the non-adherence rate was significantly higher in observational studies vs. clinical trials (46.6 ± 21.6% vs. 19.6 ± 20.5%, p < 0.001) and in North American vs. European and Asian studies (54.4 vs. 22.6 vs. 3.9%, respectively, p < 0.001) (Figure 2C,D). Considering separately observational studies and trials in the three geographic areas, a significant difference in the non-adherence rate is highlighted in North American studies (67 vs. 34%, p < 0.05) (Figure 2E). A non-significant difference has been observed when comparing the non-adherence rate of studies with different methods of adherence evaluation, different study numerosity, and monocentric vs. multicentric studies. At the multivariate analysis, only the geographical area of North America was associated with a high non-adherence rate (>50%) in the studies (p < 0.0001), while trial type of the study (p < 0.01) and the geographical area of Asia (p < 0.005) were both significantly associated with a low non-adherence rate (<10%).

Figure 2.

The non-adherence rate in published studies. (A) The non-adherence rate (%) in the 34 studies included in the meta-analysis; (B) box plot with representation of the upper and lower values, median, and interquartile range for the non-adherence rate in the included studies; (C) the significant different non-adherence rate in observational studies vs. trials; (D) the significant different non-adherence rate in studies from North America, Europe and Asia; (E) considering separately observational studies and trials in the different geographic areas, significant difference emerged in North American studies. NA = North America, EU = Europe, * = p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001, *** = p < 0.0001.

4. Discussion

Despite the widespread recognition of non-adherence in chronic disease management, this issue remains particularly overlooked in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) therapy. A recent web-based survey conducted in the United Kingdom, which included 98 clinicians, revealed that non-adherence in IBD patients was considered an infrequent problem by the majority of respondents (57%). Moreover, only 25% of clinicians regularly screen for adherence, and of those, just 40% use validated tools [50]. These findings reflect the broader clinical misperception regarding the significance of non-adherence in IBD patients. Similarly, an Italian survey conducted by the Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists (AIGO) reported that more than 65% of the 179 hospital-based gastroenterologists surveyed did not consider non-adherence to oral mesalamine in ulcerative colitis (UC) patients to be a significant issue for their own practice (submitted).

This underestimation of the problem is mirrored by the inconsistent data reported in the literature. Studies on non-adherence in UC vary greatly in terms of study design, sample size, methodology, and reported adherence rates, which range from as low as 2% to as high as 72%. Our meta-analysis aimed to address this variability by providing a more precise estimate of the non-adherence rate. We found that the type of study design significantly influenced adherence rates, with clinical trials reporting a much lower mean non-adherence rate compared to observational studies (19.6% vs. 46.8%). This discrepancy is not surprising and not specific for UC patients, as clinical trials typically offer an idealized environment with close patient monitoring and stringent protocols, which may artificially enhance adherence. In contrast, real-world observational studies are subject to numerous confounding factors that can distort adherence measurements, making them more reflective of everyday clinical practice [51]. These real-life studies offer a more accurate portrait of the true burden of non-adherence, providing valuable insights for clinicians who must manage this issue in routine practice.

Another factor that appears to influence non-adherence rate in our meta-analysis is the geographic area of the study. In fact, studies from North America reported significantly higher non-adherence rates compared to European and Asian studies. Indeed, in North America, several variables may contribute to a higher non-adherence rate, such as health insurance related issues and the presence of multiple ethnic groups with potential different adherence trend [52,53]. Moreover, living in a highly industrialized country with more people in a full-time job could induce non-adherent behavior. Indeed, a full-time occupation has been linked to non-adherence in the landmark study by Kane et al. [14]. On the contrary, Asian studies and, in particular, studies from Japan (three-quarters of Asian studies in our meta-analysis), report a high adherence rate, probably reflecting the obedient nature of Japanese people, as previously reported in the literature [49]. Alternatively, the reported difference may be explained by the low numbers of Asian studies, that are all trials, potentially affecting the low non-adherence rate reported. On the other hand, many US studies reported very large observational investigations from health system databases, with a markedly high non-adherence rate reported.

The heterogeneity in adherence rates across studies may also be partly attributed to the diverse methods used to measure adherence [54]. In clinical practice, direct questioning and non-validated questionnaires are often used due to their simplicity. However, these methods are subject to patient reluctance to admit non-adherence and a lack of standardization, which can lead to inaccurate results. More objective methods, such as urine metabolite measurements, though more accurate, are costly and not readily available in most clinical settings. Prescription or tablet count methods, while seemingly straightforward, may not accurately reflect actual drug consumption, as patients can refill prescriptions without consistently taking their medication. The eight-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) is a more formalized tool that has gained traction as a feasible option for adherence assessment [55]. However, its utility in IBD remains debated. For instance, de Castro et al. found that MMAS-8 underperformed when compared to pharmacy refill measurements, with a non-adherence rate of 22.4% versus 37%, respectively, likely due to the tool’s low specificity and negative predictive value [56]. Despite these limitations, MMAS-8 remains one of the most accessible tools for evaluating adherence in clinical practice, offering a pragmatic balance between feasibility and accuracy.

This study aimed to provide a comprehensive evaluation of non-adherence to oral mesalamine in UC patients by synthesizing data from the available literature. For the first time, we attempted to critically analyze the substantial variability in adherence rates reported across studies. While we limited our search to a specific patient population (adult UC patients) and a specific therapy (oral mesalamine), significant heterogeneity persisted, complicating efforts to draw definitive conclusions. When analyzing clinical trials and observational studies separately, some of the variability was reduced, suggesting that study design plays a critical role in determining adherence rates. However, the data remain discrepant, and it is likely that an absolute, universally applicable non-adherence rate is difficult to establish. The observed variability highlights the need for standardized methodologies in future studies, particularly in observational settings where real-world factors may obscure the true extent of non-adherence.

One of the hot topics that has emerged in the last decade in the management of IBD patients is the potential application of personalized medicine; the idea that the therapeutic strategy should ideally be tailored on single patients considering several clinical variables (disease type, location, pattern, comorbidities, etc.) and, in the future, specific molecular biomarkers. Besides the right choice of the drugs available in the market, personalized medicine means the individual approach by the physician to a person, before viewing them as a patient, that comes to our attention for a specific medical problem as they carry with them a personal history and different experiences and attitudes toward the disease that should be necessarily considered and addressed for an effective and positive doctor–patient interaction. The issue of the adherence to medical therapy offers a paradigmatic example of that.

In fact, several factors contribute to non-adherence in UC patients and understanding these is key to developing effective interventions [57]. When a patient is in an active phase of the disease, the discomfort caused by symptoms typically outweighs concerns about the inconveniences of mesalamine therapy, such as the need for constant dosing, potential side effects, or the psychological burden of feeling “sick”. However, once the disease enters remission, these concerns often resurface, leading patients to deprioritize or discontinue their medication. This pattern of behavior is consistent with the five dimensions of non-adherence described by the WHO: social and economic factors, healthcare system-related factors, condition-related factors, patient-related factors, and therapy-related factors. While some of these factors are external and unmodifiable (e.g., socioeconomic status or healthcare access), others—such as patient- and therapy-related factors—can be addressed through targeted interventions. For instance, a strong patient–doctor relationship, characterized by clear communication, empathy, and trust, can significantly improve adherence. Educating patients about the chronic nature of UC and the importance of consistent medication use, even during remission, can foster greater adherence and improve clinical outcomes. Certain sub-groups of patients may be at a higher risk of non-adherence, including younger individuals, those with a recent diagnosis, employed patients, and those in remission [58]. In these populations, regular assessment of adherence and careful exploration of the potential barriers to compliance are crucial for preventing disease flares and maintaining quality of life. Simple strategies, such as patients’ engagement in decision-making, simplifying dosing regimens, and providing tailored educational materials, may mitigate some of the challenges these patients face. Furthermore, adherence should not be assumed but rather routinely assessed, particularly in those at high risk for non-compliance.

The present study confirms that non-adherence to oral mesalamine in UC patients is a more pervasive problem than often recognized. Although the exact magnitude of non-adherence remains difficult to define due to the variability across studies, it is clear that non-adherence rates are likely higher than previously expected. Given the well-documented association between non-adherence and negative clinical outcomes, clinicians must take a proactive approach to addressing this issue. The present work should further underline the importance of personalized medicine in the approach to UC patients; besides guidelines and the standardization of care, the personal and specific physician–patient relationship may still make the difference for optimal management of the disease. Specifically, routine monitoring of adherence should become a standard practice, and clinicians should work collaboratively with patients to identify and overcome barriers to compliance. Simple interventions, such as motivational interviewing, reminder systems, and involving family members in treatment plans, could significantly improve adherence rates.

At the same time, scientific societies and professional organizations have a key role to play in raising awareness about the importance of adherence. These organizations should promote further research into non-adherence, encourage the development of standardized assessment tools, and issue guidelines that support clinicians in managing this issue. Given the complexity of adherence behavior, multifaceted approaches that integrate patient education, healthcare system improvements, and supportive therapies are likely to be the most successful in improving adherence and, consequently, patient outcomes.

5. Conclusions

The present study highlights the complexity and significance of non-adherence to oral mesalamine in UC patients. While the true prevalence of non-adherence is difficult to pinpoint, it is evident that this issue deserves greater attention from both clinicians and researchers. Improving adherence should be a priority in the management of UC, as doing so can lead to better disease control, improved patient quality of life, and reduced healthcare costs. In a modern vision of the management of IBD patients, personalized medicine with counseling, and the identification and addressing of specific individual problems can lead to an improvement of the effectiveness of medical therapy, a reduction in disease complications, and a promotion of a higher quality of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P., E.A. and M.C.D.P.; methodology, C.P. and E.A.; formal analysis, C.P. and E.A.; investigation, C.P., E.A. and B.S.; data curation, C.P. and E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P. and E.A.; writing—review and editing, C.P., M.C., M.S., R.V., G.M. and M.C.D.P.; supervision, AIGO IBD commission. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Acknowledgments

AIGO IBD Commission: Elisabetta Antonelli, Ospedale Santa Maria della Misericordia, Perugia, Italy, antelibetta@yahoo.com; Andrea Cassinotti, ASST Sette Laghi, Varese, Italy, andrea.cassinotti@asst-settelaghi.it; Linda Ceccarelli, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Pisana, Pisa, Italy, ceccarellilinda@gmail.com; Michele Comberlato, Ospedale Centrale di Bolzano, Italy, michele.comberlato@sabes.it; Antonio Cuomo, Ospedale Umberto I Nocera Inferiore A.S.L. Salerno, Italy, drcuomo@iol.it; Tiziana Grasso, Ospedale Centrale di Bolzano, Italy, tiziana.grasso@sabes.it; Ileana Luppino, Azienda Ospedaliera di Cosenza, Italy, ileana.luppino@gmail.com; Giammarco Mocci, Azienda Ospedaliera “G. Brotzu”, Cagliari, Italy, giammarco.mocci@gmail.com; Cristiano Pagnini, AO S. Giovanni Addolorata, Roma, Italy, cpagnini@hsangiovanni.roma.it; Rossella Pumpo, ASL Napoli 1, Italy, rossella.pumpo@aslnapoli1centro.it; Barbara Scrivo, “ARNAS Civico—Di Cristina—Benfratelli” Hospital, Palermo, Italy, barbara.scrivo@gmail.com; Angela Variola, IRCCS Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Negrar, Italy, angela.variola@gmail.com; and Maria Carla Di Paolo (head), AO S. Giovanni Addolorata, Roma, Italy; mcdipaolo@hsangiovanni.roma.it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel diseases |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| 5-ASA | 5-aminosalicylic acid |

| MMAS | Morisky Medication Adherence Scale |

References

- Sabaté, E. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Religioni, U.; Barrios-Rodríguez, R.; Requena, P.; Borowska, M.; Ostrowski, J. Enhancing Therapy Adherence: Impact on Clinical Outcomes, Healthcare Costs, and Patient Quality of Life. Medicina 2025, 61, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnier, M. The role of adherence in patients with chronic diseases. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 119, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunbar-Jacob, J.; Erlen, J.A.; Schlenk, E.A.; Ryan, C.M.; Sereika, S.M.; Doswell, W.M. Adherence in chronic disease. Annu. Rev. Nurs. Res. 2000, 18, 48–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcântara, L.; Figueiredo, T.; Costa, E. Exploring the Perceptions and Self-Perceptions of Therapeutic Adherence in Older Adults with Chronic Conditions: A Scoping Review. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2025, 19, 503–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Berre, C.; Honap, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2023, 402, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, B.; Kaplan, G.G. Ulcerative Colitis in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordas, I.; Eckmann, L.; Talamini, M.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sandborn, W.J. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2012, 380, 1606–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Magro, F.; Dignass, A.; Al Awadhi, S.; Gutierrez Casbas, A.; Queiroz, N.S.F.; Rydzewska, G.; Duk Ye, B.; Ran, Z.; Hart, A.; et al. Practical management of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: An international expert consensus. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 18, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, P.; Wellens, J.; Verstockt, B.; Ferrante, M.; Sabino, J.; Vermeire, S. Holistic healthcare in inflammatory bowel disease: Time for patient-centric approaches? Gut 2023, 72, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, T.; Bonovas, S.; Burisch, J.; Kucharzik, T.; Adamina, M.; Annese, V.; Bachmann, O.; Bettenworth, D.; Chaparro, M.; Czuber-Dochan, W.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Medical Treatment. J. Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Berre, C.; Roda, G.; Nedeljkovic Protic, M.; Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Modern use of 5-aminosalicylic acid compounds for ulcerative colitis. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2020, 20, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, D.; Hodgkins, P.; Yen, L.; Davis, K.L.; Cohen, R.D. Association between oral 5-ASA adherence and health care utilization and costs among patients with active ulcerative colitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012, 12, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, S.; Huo, D.; Aikens, J.; Hanauer, S. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am. J. Med. 2003, 114, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, A.; Castiglione, F.; Nardone, O.M.; Colombo, G.L. Adherence in ulcerative colitis: An overview. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2017, 11, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, G.; Hungin, A.P.; Chinn, D.; Dwarakanath, A.D.; Green, L.; Bates, J. Long-term aminosalicylate therapy is under-used in patients with ulcerative colitis: A cross-sectional survey. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 16, 1889–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, S.; Huo, D.; Magnanti, K. A pilot feasibility study of once daily versus conventional dosing mesalamine for maintenance of ulcerative colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2003, 1, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; Park, S.H.; Eun, C.S.; Seo, G.S.; Im, J.P.; Kim, T.O.; Park, D.I. Adherence to Asacol once daily versus divided regimen for maintenance therapy in ulcerative colitis: A prospective, multicenter, randomized study. Intest. Res. 2019, 17, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignass, A.U.; Bokemeyer, B.; Adamek, H.; Mross, M.; Vinter-Jensen, L.; Borner, N.; Silvennoinen, J.; Tan, G.; Pool, M.O.; Stijnen, T.; et al. Mesalamine once daily is more effective than twice daily in patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 7, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, S.; Holderman, W.; Jacques, P.; Miodek, T. Once daily versus conventional dosing of pH-dependent mesalamine long-term to maintain quiescent ulcerative colitis: Preliminary results from a randomized trial. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2008, 2, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, A.B.; Stenson, R.; Gillespie, D.; Swarbrick, E.T.; Dhar, A.; Kapur, K.C.; Hood, K.; Probert, C.S. One-year investigator-blind randomized multicenter trial comparing Asacol 2.4 g once daily with 800 mg three times daily for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruis, W.; Jonaitis, L.; Pokrotnieks, J.; Mikhailova, T.L.; Horynski, M.; Batovsky, M.; Lozynsky, Y.S.; Zakharash, Y.; Racz, I.; Kull, K.; et al. Randomised clinical trial: A comparative dose-finding study of three arms of dual release mesalazine for maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamm, M.A.; Lichtenstein, G.R.; Sandborn, W.J.; Schreiber, S.; Lees, K.; Barrett, K.; Joseph, R. Randomised trial of once- or twice-daily MMX mesalazine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Gut 2008, 57, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prantera, C.; Kohn, A.; Campieri, M.; Caprilli, R.; Cottone, M.; Pallone, F.; Savarino, V.; Sturniolo, G.C.; Vecchi, M.; Ardia, A.; et al. Clinical trial: Ulcerative colitis maintenance treatment with 5-ASA: A 1-year, randomized multicentre study comparing MMX with Asacol. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 30, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, D.; Martin, B.; Caldera, F. Use of an iPhone Application to Increase Adherence in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis in Remission: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, e33–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, M.P.; Marti-Aguado, D.; Fullana, M.; Bosca-Watts, M.M.; Tosca, J.; Romero, E.; Sanchez, A.; Navarro-Cortes, P.; Anton, R.; Mora, F.; et al. Impact and risk factors of non-adherence to 5-aminosalicylates in quiescent ulcerative colitis evaluated by an electronic management system. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2019, 34, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagisawa, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Ozaki, R.; Okabayashi, S.; Toyonaga, T.; Miura, M.; Hayashida, M.; Saito, E.; Nakano, M.; Matsubara, H.; et al. Randomized, crossover questionnaire survey of acceptabilities of controlled-release mesalazine tablets and granules in ulcerative colitis patients. Intest. Res. 2019, 17, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, R.; Wasserbauer, M.; Zadorova, Z.; Kojecky, V.; Hlava, S.; St’ovicek, J.; Chudy, J.; Roznetinska, M.; Drabek, J.; Kubisova, N.; et al. Adherence, risk factors of non-adherence and patient’s preferred treatment strategy of mesalazine in ulcerative colitis: Multicentric observational study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 53, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignass, A.; Schnabel, R.; Romatowski, J.; Pavlenko, V.; Dorofeyev, A.; Derova, J.; Jonaitis, L.; Dilger, K.; Nacak, T.; Greinwald, R.; et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel high-dose mesalazine tablet in mild to moderate active ulcerative colitis: A double-blind, multicentre, randomised trial. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2018, 6, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaus, S.; Schreiber, S.; Siegmund, B.; Bokemeyer, B.; Bastlein, E.; Bachmann, O.; Gorlich, D.; Hofmann, U.; Schwab, M.; Kruis, W. Patient Education in a 14-month Randomised Trial Fails to Improve Adherence in Ulcerative Colitis: Influence of Demographic and Clinical Parameters on Non-adherence. J. Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Iida, M.; Ito, H.; Nishino, H.; Ohmori, T.; Arai, T.; Yokoyama, T.; Okubo, T.; Hibi, T. 2.4 g Mesalamine (Asacol 400 mg tablet) Once Daily is as Effective as Three Times Daily in Maintenance of Remission in Ulcerative Colitis: A Randomized, Noninferiority, Multi-center Trial. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Algaba, A.; Guerra, I.; Garcia Garcia de Paredes, A.; Hernandez Tejero, M.; Ferre, C.; Bonillo, D.; Aguilera, L.; Lopez-Sanroman, A.; Bermejo, F. What is the real-life maintenance mesalazine dose in ulcerative colitis? Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2017, 109, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kane, S.; Katz, S.; Jamal, M.M.; Safdi, M.; Dolin, B.; Solomon, D.; Palmen, M.; Barrett, K. Strategies in maintenance for patients receiving long-term therapy (SIMPLE): A study of MMX mesalamine for the long-term maintenance of quiescent ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshkovska, T.; Stone, M.A.; Clatworthy, J.; Smith, R.M.; Bankart, J.; Baker, R.; Wang, J.; Horne, R.; Mayberry, J.F. An investigation of medication adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis, using self-report and urinary drug excretion measurements. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 30, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, S.; Shaya, F. Medication non-adherence is associated with increased medical health care costs. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2008, 53, 1020–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, S.V.; Cohen, R.D.; Aikens, J.E.; Hanauer, S.B. Prevalence of nonadherence with maintenance mesalamine in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 96, 2929–2933. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, N.; Thielsen, P.; Martinsen, L.; Bennedsen, M.; Haaber, A.; Langholz, E.; Vegh, Z.; Duricova, D.; Jess, T.; Bell, S.; et al. eHealth: Individualization of mesalazine treatment through a self-managed web-based solution in mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 2276–2285. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, D.; Hood, K.; Farewell, D.; Stenson, R.; Probert, C.; Hawthorne, A.B. Electronic monitoring of medication adherence in a 1-year clinical study of 2 dosing regimens of mesalazine for adults in remission with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N.; Abbas, A.M.; Bazzano, L.A.; Koleva, Y.N.; Krousel-Wood, M. Long-term oral mesalazine adherence and the risk of disease flare in ulcerative colitis: Nationwide 10-year retrospective cohort from the veterans affairs healthcare system. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 36, 755–764. [Google Scholar]

- Lachaine, J.; Yen, L.; Beauchemin, C.; Hodgkins, P. Medication adherence and persistence in the treatment of Canadian ulcerative colitis patients: Analyses with the RAMQ database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, L.; Wu, J.; Hodgkins, P.L.; Cohen, R.D.; Nichol, M.B. Medication use patterns and predictors of nonpersistence and nonadherence with oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 2012, 18, 701–712. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, S.; Panes, J.; Louis, E.; Holley, D.; Buch, M.; Paridaens, K. National differences in ulcerative colitis experience and management among patients from five European countries and Canada: An online survey. J. Crohns Colitis 2013, 7, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgkins, P.; Swinburn, P.; Solomon, D.; Yen, L.; Dewilde, S.; Lloyd, A. Patient preferences for first-line oral treatment for mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: A discrete-choice experiment. Patient 2012, 5, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, S.V.; Sumner, M.; Solomon, D.; Jenkins, M. Twelve-month persistency with oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for ulcerative colitis: Results from a large pharmacy prescriptions database. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2011, 56, 3463–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshkovska, T.; Stone, M.A.; Smith, R.M.; Bankart, J.; Baker, R.; Mayberry, J.F. Impact of a tailored patient preference intervention in adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid medication in ulcerative colitis: Results from an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 1874–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, A.C.; Chaudhary, N.; Tukey, M.; Junior, J.; Cury, D.; Falchuk, K.R.; Cheifetz, A.S. Impact of a patient-support program on mesalamine adherence in patients with ulcerative colitis—A prospective study. J. Crohns Colitis 2010, 4, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Hanai, H.; Nishino, H.; Yokoyama, T.; Terada, T.; Suzuki, Y. Comparison of QD and TID oral mesalazine for maintenance of remission in quiescent ulcerative colitis: A double-blind, double-dummy, randomized multicenter study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, A.; Tanaka, M.; Choong, L.M.; Kunisaki, R.; Maeda, S.; Bjarnason, I.; Hayee, B. Self-Reported Medication Adherence Among Patients with Ulcerative Colitis in Japan and the United Kingdom: A Secondary Analysis for Cross-Cultural Comparison. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2022, 16, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soobraty, A.; Boughdady, S.; Selinger, C.P. Current practice and clinicians’ perception of medication non-adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A survey of 98 clinicians. World, J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 8, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.E.; Booth, C.M. Real-world data: Bridging the gap between clinical trials and practice. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 78, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Goering, M.M.; Roy, K.; Howard, D.H. Peer reviewed: Relationship between adherence to antihypertensive medication regimen and out-of-pocket costs among people aged 35 to 64 with employer-sponsored health insurance. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2019, 16, E32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoni, J.M.; Huh, D.; Wilson, I.B.; Shen, J.; Goggin, K.; Reynolds, N.R.; Remien, R.H.; Rosen, M.I.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Liu, H. Racial/Ethnic disparities in ART adherence in the United States: Findings from the MACH14 study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2012, 60, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anghel, L.A.; Farcas, A.M.; Oprean, R.N. An overview of the common methods used to measure treatment adherence. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2019, 92, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Muñoz, A.M.; Victoria-Montesinos, D.; Cerdá, B.; Ballester, P.; de Velasco, E.M.; Zafrilla, P. Self-Reported Medication Adherence Measured with Morisky Scales in Rare Disease Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, M.L.; Sanroman, L.; Martin, A.; Figueira, M.; Martinez, N.; Hernandez, V.; Del Campo, V.; Pineda, J.R.; Martinez-Cadilla, J.; Pereira, S.; et al. Assessing medication adherence in inflammatory bowel diseases. A comparison between a self-administered scale and a pharmacy refill index. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2017, 109, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, K.; Dong, J.; Mishkin, B.F.; Feuerstein, J.D. Patient Preference and Adherence to Aminosalicylates for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2021, 14, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Inca, R.; Bertomoro, P.; Mazzocco, K.; Vettorato, M.G.; Rumiati, R.; Sturniolo, G.C. Risk factors for non-adherence to medication in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 27, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).