Personalized Medicine for Chronic Diseases Through the Integration of Health Determinants Control in Patients: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

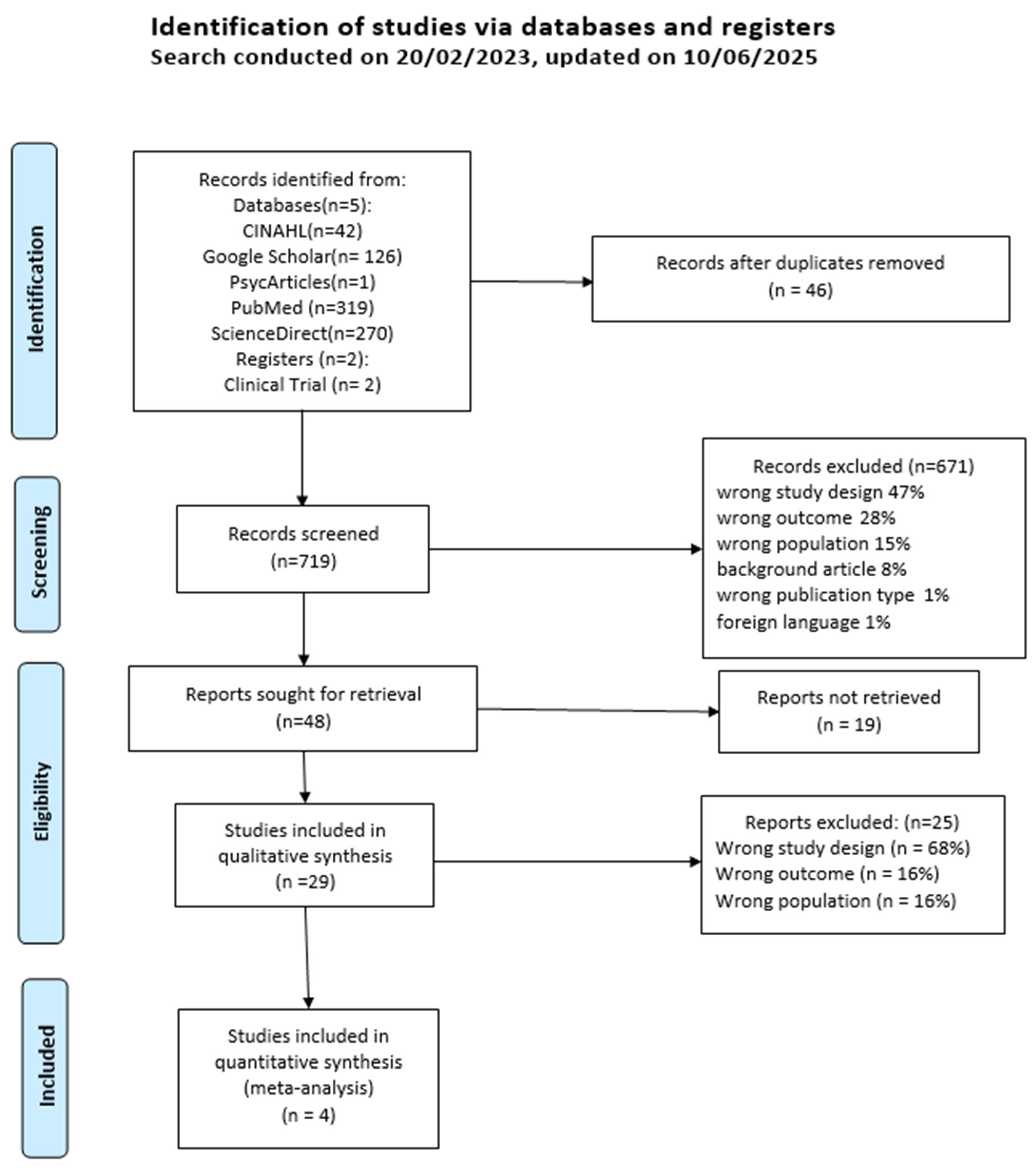

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Analysis

2.2. Summary of Conclusions and Assessment of the Certainty of the Evidence

2.3. Protocol Amendments

2.4. Summary Box

3. Results

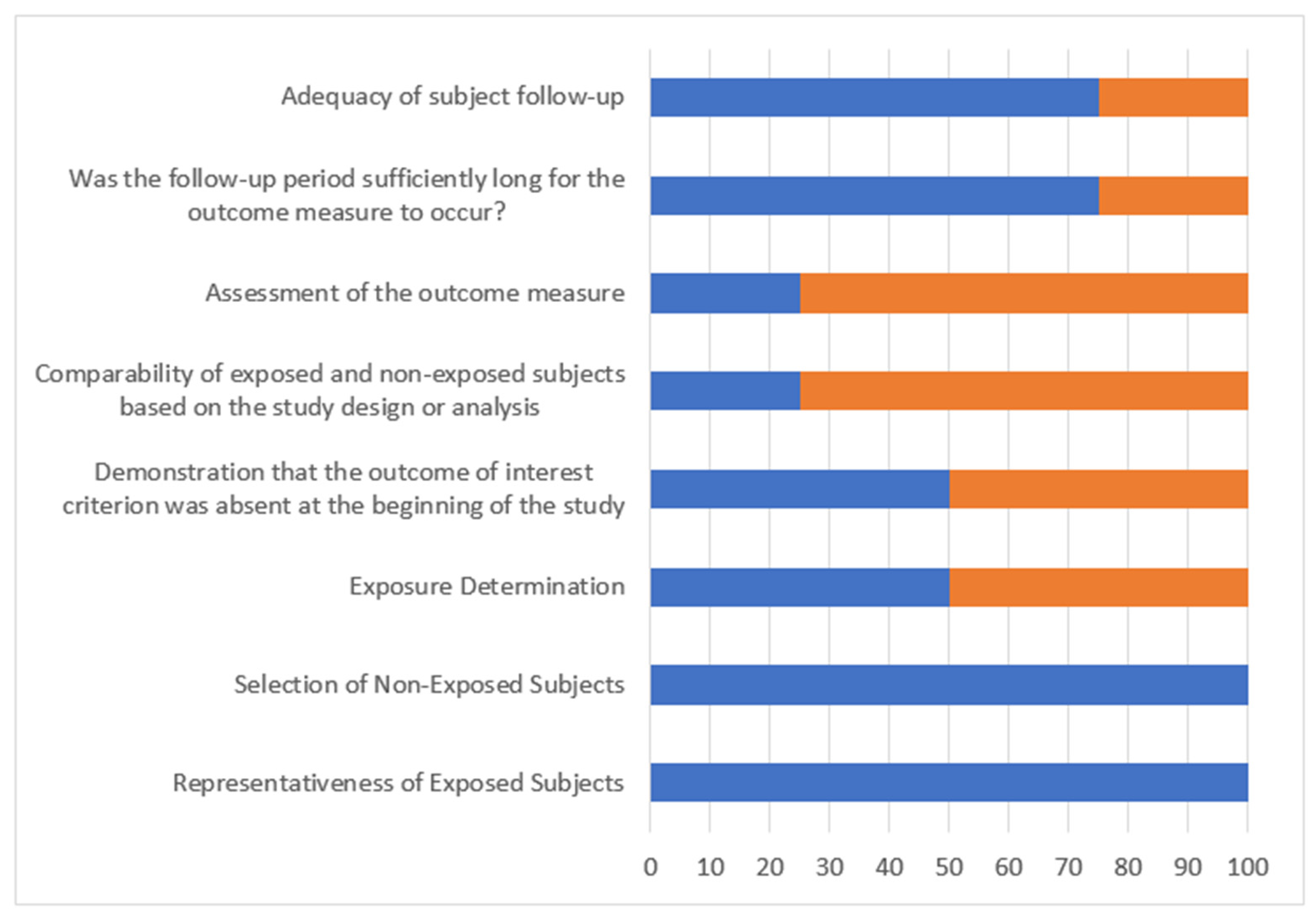

Risk of Bias in Included Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. External Consistency

4.2. Clinical Relevance

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statements

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OMS Maladies non Transmissibles. Available online: https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Castaing E (DREES/DIRECTION). L’état de Santé de la Population en France; Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé Direction de la Recherche, des Etudes, de L’évaluation et des Statistiques (DREES): Paris, France, 2022; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation Mondiale de la Sante. Documents Fondamentaux [Internet], 48e ed; Organisation mondiale de la Santé: Genève, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/202595 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Ellefsen, E. La Santé-Dans-La-Maladie: Un Nouveau Modèle Pour Comprendre l’expérience Universelle de La Maladie Chronique. Rech. Qual. 2013, 15, 132–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ellefsen, É.; Cara, C. L’expérience de santé-dans-la-maladie: Une rencontre entre la souffrance et le pouvoir d’exister pour des adultes vivant avec la sclérodermie systémique. Rech. Soins Infirm. 2015, 121, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindig, D.A. Understanding Population Health Terminology. Milbank Q. 2007, 85, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumont, D.; Aujoulat, I. L’empowerment et L’éducation du Patient; UCL, Louvain: Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 2002; Volume 21. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon, J. Empowerment. In Les Concepts en Sciences Infirmières; Hors Collection; Association de Recherche en Soins Infirmiers: Toulouse, France, 2012; pp. 172–175. ISBN 978-2-9533311-3-4. [Google Scholar]

- Stepanian, N.; Larsen, M.H.; Mendelsohn, J.B.; Mariussen, K.L.; Heggdal, K. Empowerment Interventions Designed for Persons Living with Chronic Disease—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Components and Efficacy of Format on Patient-Reported Outcomes. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotter, J.B. Generalized Expectancies for Internai Versus External Control of Reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. 1966, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H.; (HLS-EU) Consortium. Health Literacy Project European Health Literacy and Public Health: A Systematic Review and Integration of Definitions and Models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekkers, O.M.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Cevallos, M.; Renehan, A.G.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M. COSMOS-E: Guidance on Conducting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies of Etiology. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A.; Locke, E.A. Negative Self-Efficacy and Goal Effects Revisited. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, D.; Blickem, C.; Vassilev, I.; Brooks, H.; Kennedy, A.; Richardson, G.; Rogers, A. The Contribution of Social Networks to the Health and Self-Management of Patients with Long-Term Conditions: A Longitudinal Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, L.; Villegente, J.; Loyal, D.; Ayav, C.; Kivits, J.; Rat, A. Tailored Patient Therapeutic Educational Interventions: A Patient-centred Communication Model. Health Expect. Int. J. Public Particip. Health Care Health Policy 2022, 25, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenning, C.; Coventry, P.A.; Gibbons, C.; Bee, P.; Fisher, L.; Bower, P. Does Patient Experience of Multimorbidity Predict Self-Management and Health Outcomes in a Prospective Study in Primary Care? Fam. Pract. 2015, 32, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, I.-H.; Chi, M. Effects of Self-Care Behaviors on Medical Utilization of the Elderly with Chronic Diseases—A Representative Sample Study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 60, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Health Status Notions Identified in the Articles | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How the Health Determinants Were Described by Authors of Each Article | Variables Describing Control on Health Determinants, Listed in the Articles | Adjustment Factors (Confounders) | Tick if Articles Identify Some Form of Control over the Variables in the Second Column | Frequent Contact with GP | General Medicine Use Outside of Practice | Unplanned Hospitalizations | Poor Health-Related Quality of Life | Emergency Consultations | Planned Hospitalizations | Avoidable Hospitalizations | Self-Management | Health Behaviors | Physical Health | Emotional Well-Being | Cost of Health Services | QUALYs Over The Last 12 Months | Self-Assessment of Health Status |

| Illness Perception | Illness Consequences | X | Rijken et al., 2020, [19] Dutch aged 15 and over with at least 2 chronic conditions n = 747 | ||||||||||||||

| Timeline | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Personal Control | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Treatment Control | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Identity | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Worry | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Illness Understanding | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Emotional Response | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Personal Resources | Education Level | X | |||||||||||||||

| Financial Management | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Health Provider Support | |||||||||||||||||

| Having Sufficient Information | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Active Health Management | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Social Support | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Critical Evaluation | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Active Engagement with Health Care Providers | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Navigating the Health Care System | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Ability to Find Good Health Information | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Reading and Understanding Health Information | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Mastery | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Anxiety and Depression | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Confidence in Self-care | Adherence | X | Chen et al., 2015 [18], Taiwanese aged 65 and over, 80% with at least one chronic condition n = 2531 | ||||||||||||||

| Exercise | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Diet | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Ability to Express Health Conditions | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Ability to Solicit | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Ability to Control Illness | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Ability to Control Emotions | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Disease Management Behavior (Past Year) | Weight Control | X | |||||||||||||||

| Smoking | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Exercise | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Follows a Diet | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Adaptation to Daily Life | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Age | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Gender | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Education | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Ethnicity | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Marital Status | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Employment Status | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Living Conditions | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Living Area | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Number of Chronic Diseases | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Fall Experience | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Disabilities in Daily Activities | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Depressive Symptoms | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Cognitive Disorders | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Self-assessment of Health | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Gender | X | Reeves et al., 2014 [16], Heart failure or diabetic patients recruited in Greater Manchester n = 248 | |||||||||||||||

| Age | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Main Condition | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Number of Long-term Conditions | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Living Area Precarity | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Ethnicity | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Socio-professional Class | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Education | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Income | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Characteristics of Network Members | Number of Children Nearby | X | |||||||||||||||

| Contact Frequency | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Number of Co-inhabitants | |||||||||||||||||

| Partner | |||||||||||||||||

| Characteristics of the Social Network | Network Density | X | |||||||||||||||

| Network Variety | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Participation in Local Support Groups | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Support Given to Others | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Social Resources | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Support Provided by the Network for Illness Management | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Emotional Support Provided by the Network | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Network Support in Daily Tasks | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Network Change Measures | Loss of One or More Important Network Members | X | |||||||||||||||

| Loss of Network Support | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Gender | Kenning et al., 2015 [17], Patients with at least 2 conditions among COPD, coronary diseases, diabetes, osteoarthritis, depression; recruited in Greater Manchester n = 410 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||||||||

| Professional Activity | |||||||||||||||||

| Age | |||||||||||||||||

| Living Area Precarity | |||||||||||||||||

| Number of Long-term Conditions | |||||||||||||||||

| Anxiety and Depression | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Health Status | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Care Services Experiences | Experience in Care Organization | X | |||||||||||||||

| Care Concerns | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Illness Perception | Illness Consequences | X | |||||||||||||||

| Personal Control | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Treatment Control | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Experience of Multimorbidity | X | ||||||||||||||||

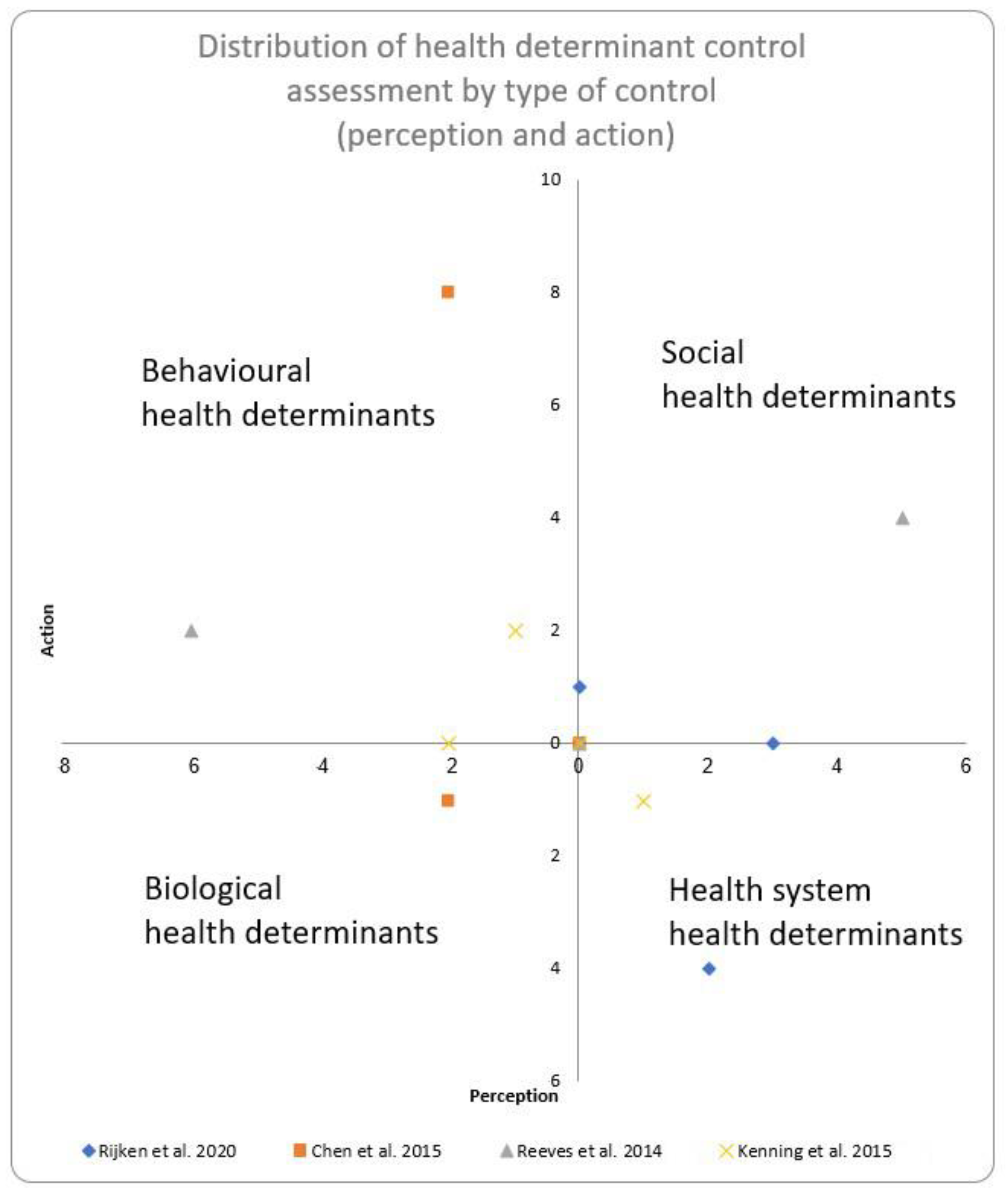

| Determinant of Health Category (Kindig) | How the Determinant was Measured | What the Patient Thinks He does (Perception) Versus What He Actually Does (Action) (Bandura and Rotter) | Study | Number of Health Determinant Descriptors Found |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Determinants | Income | Perception | Rijken et al. [19] | 1 |

| Social Determinants | Social Support | Perception | Rijken et al. [19] | 1 |

| Social Determinants | Locus of Control | Perception | Rijken et al. [19] | 1 |

| Social Determinants | Social Support | Perception | Reeves et al. [16] | 5 |

| Social Determinants | Social Support | Action | Reeves et al. [16] | 4 |

| Health System Determinants | Access to Care | Perception | Rijken et al. [19] | 1 |

| Health System Determinants | Access to Care | Perception | Kening et al. [17] | 1 |

| Health System Determinants | Access to Care | Action | Kenning et al. [17] | 1 |

| Health System Determinants | Access to Care | Action | Rijken et al. [19] | 3 |

| Health System Determinants | Quality of Care | Perception | Rijken et al. [19] | 1 |

| Health System Determinants | Quality of Care | Action | Rijken et al. [19] | 1 |

| Behavioral Determinants | Diet | Perception | Chen et al. [18] | 1 |

| Behavioral Determinants | Diet | Action | Chen et al. [18] | 1 |

| Behavioral Determinants | Physical Exercise | Perception | Chen et al. [18] | 1 |

| Behavioral Determinants | Physical Exercise | Action | Chen et al. [18] | 1 |

| Behavioral Determinants | Consumption | Action | Chen et al. [18] | 2 |

| Behavioral Determinants | Illness | Perception | Reeves et al. [16] | 6 |

| Behavioral Determinants | Illness | Perception | Kenning et al. [17] | 1 |

| Behavioral Determinants | Illness | Action | Reeves et al. [16] | 2 |

| Behavioral Determinants | Illness | Action | Kenning et al. [17] | 2 |

| Behavioral Determinants | Illness | Action | Chen et al. [18] | 4 |

| Behavioral Determinants | Illness | Action | Rijken et al. [19] | 1 |

| Biological Determinants | Anxiety and Depression | Perception | Kenning et al. [17] | 1 |

| Biological Determinants | Anxiety and Depression | Perception | Chen et al. [18] | 1 |

| Biological Determinants | Anxiety and Depression | Action | Chen et al. [18] | 1 |

| Biological Determinants | Cognitive Capacity | Perception | Chen et al. [18] | 1 |

| Biological Determinants | Health Status | Perception | Kenning et al. [17] | 1 |

| Health Outcome Measures |

|---|

| Health Services Utilization |

| Frequent Contact with GP |

| General Medicine Use Outside the Office |

| Unplanned Hospitalizations |

| Emergency Consultations |

| Planned Hospitalizations |

| Avoidable Hospitalizations |

| Outpatient Consultations |

| Health Behaviors |

| Self-management |

| Health Behaviors |

| Health Costs |

| Cost of Health Services |

| Health Outcomes |

| Physical Health |

| Emotional Well-being |

| QUALYs over the Last 12 Months |

| Poor Health-Related Quality of Life |

| Influence of Lack of Control Over Health Determinants on Health Status (Only Significant Results are Reported) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare Outcome | Number of Studies | Study | Correlation | |

| Health System Use | 3 | |||

| Primary Care | 1 | Rijken et al. 2020 [19] | ||

| General medicine use outside surgery | (B)(+) Emotional reaction to the illness * | |||

| Frequent GP contact | (B)(+) Worry * | |||

| (B)(−) Ability to master the illness * | ||||

| Specialised care | 1 | Rijken et al. 2020 [19] | ||

| Specialised care | (B)(−) Personal control ** | |||

| 1 | Chen et al. 2015 [18] | |||

| Number of avoidable hospitalisations | (OR)(−) Initiated physical activity (95% CI: 0.43–0.82) *** | |||

| (OR)(−) Self-care confidence (95% CI: 0.94–0.99) * | ||||

| (OR)(+) ADL disability (95% CI: 1.10–2.56) * | ||||

| Number of emergency consultations | (OR)(−) Initiated physical activity (95% CI: 0.59–0.96) * | |||

| (OR)(+) Symptoms of depression (95% CI: 1.02–1.72) * | ||||

| Number of outpatient consultations | (OR)(−) Initiated physical activity (95% CI: 0.55–0.93) * | |||

| Healthcare service costs | 1 | |||

| 1 | Reeves et al. 2014 [16] | |||

| Cost of health care services | (B)(−) Help the patient’s network provides to manage illness(SE = 8.61) ** | |||

| QUALYs (over the last 12 months) | (B)(−) Social involvement (SE = 2.34) ** | |||

| health behaviours | 2 | |||

| Self-management | 1 | Reeves et al. 2014 [16] | (B)(+) Support given to others (SE = 0.029) * | |

| (B)(+) Help the patient’s network provides to manage illness (SE = 0.002) * | ||||

| (B)(+) Social involvement (SE = 0.021) * | ||||

| Health Behaviour | 1 | Reeves et al. 2014 [16] | (B)(+) Help the patient’s network provides to manage illness (SE = 0.007) * | |

| Health outcomes | 2 | |||

| Quality of Life | 1 | Reeves et al. 2014 [16] | ||

| (B)(+)Social involvement (SE = 1.05) ** | ||||

| (B)(+) Help the patient’s network provides to manage illness (SE = 0.11) ** | ||||

| Physical health | (B)(+) Help provided to others (SE = 0.56) * | |||

| (B)(+) Social involvement (SE=0.37) * | ||||

| 1 | Rijken et al. 2020 [19] | |||

| Quality of Life | (B)(−) Depression ** | |||

| (B)(+) Perception illness consequences ** | ||||

| (B)(+) Personal control * | ||||

| (B)(+) Identity facing illness ** | ||||

| (B)(+) “I have many people around me” * | ||||

| Selection Biais | Comparability Bias | Detection Bias | Attrition Bias | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of Exposed Subjects | Selection of Non-Exposed Subjects | Exposure Determination | Demonstration That the Outcome of Interest Criterion was Absent at the Beginning of the Study | Comparability of Exposed and Non-Exposed Subjects Based on the Study Design or Analysis | Assessment of the Outcome Measure | Was the Follow-Up Period Sufficiently Long for the Outcome Measure to Occur? | Adequacy of Subject Follow-Up | |

| Rijken (2020) [19] | X | X | X | X | XX | X | X | X |

| Chen (2015) [18] | X | X | X | X | XX | X | X | X |

| Kenninga (2015) [18] | X | X | X | X | XX | X | X | X |

| Reeves (2014) [16] | X | X | X | X | XX | X | X | X |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bremond, M.; Raigneau, M.-C.; Burnel, J.; Pautrat, M. Personalized Medicine for Chronic Diseases Through the Integration of Health Determinants Control in Patients: A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15100462

Bremond M, Raigneau M-C, Burnel J, Pautrat M. Personalized Medicine for Chronic Diseases Through the Integration of Health Determinants Control in Patients: A Systematic Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2025; 15(10):462. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15100462

Chicago/Turabian StyleBremond, Matthieu, Marie-Charlotte Raigneau, Joévin Burnel, and Maxime Pautrat. 2025. "Personalized Medicine for Chronic Diseases Through the Integration of Health Determinants Control in Patients: A Systematic Review" Journal of Personalized Medicine 15, no. 10: 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15100462

APA StyleBremond, M., Raigneau, M.-C., Burnel, J., & Pautrat, M. (2025). Personalized Medicine for Chronic Diseases Through the Integration of Health Determinants Control in Patients: A Systematic Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 15(10), 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm15100462