Abstract

Love addiction is a dysfunctional relational modality that takes on the addiction characteristics and which, for the individuals who suffer from it, can have a negative and pervasive impact on various areas of functioning. The objective of this research was the analysis the factors that can be associated with love addiction, particularly focusing on adult attachment patterns and self-esteem. A sample group of 300 individuals who declared themselves to have a romantic relationship was involved in this research (Mage = 37.83 years, SD = 12.937). They completed an online survey including the Love Addiction Inventory—Short form, Relationship Questionnaire, and Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Results showed significant and positive associations between preoccupied and fearful adult attachment and love addiction. Furthermore, these relationships were totally mediated by self-esteem. Gender and age were controlled as potential covariates and showed significant effects in influencing the levels of self-esteem and love addiction. Such findings may provide useful information for orienting future research and supporting an effective clinical practice.

1. Introduction

Love addiction is one of the “New Addictions”, a heterogeneous set of disorders that shares psychopathological characteristics with substance dependence, characterized by a spasmodic research of the object of dependence without which existence seems meaningless [1]. Despite the attempts at definition and the etiological hypotheses, this condition is not included in any official nosographic system, e.g., DSM-5 [2]. Love addiction can be defined as a maladaptive and problematic model of the love relationship, characterized by a pervasive and excessive interest in the partner, with consequent loss of control and continuation of the relationship despite the awareness of the existence of problems created by the relationship itself [3,4]. This condition is featured by an alteration of the representation of self, as an extremely needy subject of guidance, support, and protection, and of the other (the object of dependence) being extremely idealized [5]. Reynaud [4] has identified the crucial moment of transition from healthy love to pathological love when desire becomes need, suffering takes precedence over pleasure, lack becomes paramount, and when the relationship continues despite the negative consequences. The love addicted subject often feels inadequate, unworthy of love, and lives in constant fear of being abandoned by his partner. It is precisely the fear of abandonment that leads to the exacerbation of attempts to control others, with complacent behavior, sacrifice, availability, and care, in the hope that the relationship will become stable and lasting [6]. A model that has identified the fundamental components that constitute love addiction is the ‘components’ model of addiction by Griffiths [7]. The six constructs of the model are as follows: salience, i.e., directing almost all feelings, thoughts and behaviors towards the object of love; tolerance, i.e., an increasing need for time spent with, and/or time spent thinking about the loved one; mood modification, i.e., coping with emotional distress by spending time with and/or thinking about the object of love; relapse, i.e., difficulty reducing the time spent in the presence of a loved one; withdrawal, i.e., typical both psychological and physical withdrawal symptoms in the absence of the loved one; and conflict, i.e., interference with daily activities, such as work and education, friendships, activities and hobbies. There is evidence in the scientific literature on the negative consequences of this behavioral dependence, which is why a more in-depth study of this issue is needed. Love addiction is accompanied by a reduction in social, professional, and leisure activities [4], resulting in a lower quality of life; moreover, when associated with stressful life events, it can lead to a high risk of medical and psychological pathologies [8]. Subjects with love addiction may have high levels of depression and alexithymia [9] and a possible comorbidity with post-traumatic stress disorder [10] and with other types of addiction, such as sex addiction [4]. Moreover, interpersonal dependence would seem to be a factor that plays a role of strong influence on body perception, resulting in dissatisfaction with the body and unregulated nutrition [11].

1.1. Love Addiction and Attachment

Considering the strong impact and negative consequences of love addiction, the study of related factors seems particularly relevant. A first factor that can play a fundamental role in addiction is attachment. Attachment can be defined as an emotional bond in which an individual seeks the closeness of the attachment object and uses it as a safe place during times of distress and as a safe base from which to explore the world [12]. John Bowlby, in his theory of attachment [13], conceptualized the human tendency to establish emotional ties with significant others. According to Bowlby’s theory, individuals in childhood internalize experiences with their caregivers, establishing an early attachment, which lays the foundations for future relational modalities, outside the family [14]. As such, the attachment style becomes reactivated in close relationships during late adolescence and early adulthood [15]. There are individual differences in the quality of those attachments. Bartholomew and Horowitz [16] described the different attachment styles (secure, insecure preoccupied, insecure dismissing, and insecure fearful) in their “Model of Adult Attachment”, derived from a combination of two dimensions, namely “Model of self” and “Model of other”. A secure attachment style is characterized by a sense of lovability and expectation that other people will be available and responsive. Individuals with such attachment style are comfortable with intimacy and autonomy, are more optimistic about life, use more effective emotion regulation strategies, can remain open to their emotions and can express them freely to others [16,17].

A preoccupied attachment style is instead characterized by a sense of inadequacy, combined with a positive assessment of others. Individuals with such attachment style attempt by obtaining the acceptance of others to increase acceptance for themselves, indeed they search anxiously for love and support [16,18]. The third style of attachment, dismissing, implies a sense of inadequacy and the expectation that others are unavailable, and unreliable. Not feeling worthy of love, individuals with such attachment style avoid close involvement, to protect themselves from the rejection of others. The fourth and last attachment style, the fearful one, indicates a sense of lovability combined with a negative disposition towards others. Individuals with such attachment style avoid intimate relationships while maintaining a sense of independence and invulnerability, to protect themselves from disappointment. While both dismissing and fearful styles reflect avoidance of intimacy, they differ in the need for acceptance by others to maintain positive self-esteem; such a need is present in the dismissing style, but not in the fearful one. Similarly, the preoccupied and fearful styles share strong dependence on others but differ in willingness to establish intimate relationships, as preoccupied individuals actively seek closeness with others, while fearful individuals tend to avoid it [16].

Evidence in the literature shows that a type of insecure attachment is a strong risk factor for substance use disorders [19] but also for symptoms of behavioral addictions [20], such as gambling disorder [21], problematic shopping [22], problematic social media use [23], and sexual addiction [24]. Insecure attachment is also associated with love addiction in the literature and, therefore, to a vision of love characterized by obsession and dependence, confirming the hypothesis that the dynamics of attachment are not limited to childhood, but rather remain throughout the course of life [25,26,27].

1.2. Love Addiction and Self-Esteem

Another factor of great importance, which can be analyzed in relation to love addiction, is self-esteem. The latter is defined in the literature as a fundamental component of the concept of self, since it constitutes its affective orientation, understood as a positive or negative assessment of itself. This construct, therefore, appears to be in close connection with the feeling of personal value, and would seem to play a determining role in the development of coping skills and a sense of well-being [28,29]. In the relationship between self-esteem and attachment, studies that have analyzed this association have shown that a secure attachment style is related to higher levels of self-esteem than an insecure attachment style. In particular, secure attachment is associated with the “Broaden and build circle” technique, which would contribute to a positive association between self-esteem and clarity of the concept of self. Conversely, an insecure style of attachment would seem to be associated with lower levels of self-esteem and clarity of the concept of self, as people classified as insecure are less effective in using and providing a safe and consistent basis for their partners, have less satisfaction and more conflict in relationships and also report lower self-esteem [30,31,32]. Referring to the “Model of adult attachment” [16], data in the literature highlight how secure and dismissing attachment styles are associated with higher global self-esteem and greater average competence in the social, romantic, physical attractiveness, and sport domains, compared to either preoccupied or fearful attachment styles [33].

In the literature, it also emerges how self-esteem has a role in behavioral addictions. Indeed, studies show that subjects with Internet and Facebook addiction have low levels of self-esteem and show how the latter plays the role of predictor of an Internet addiction [34,35]. Low self-esteem is also a contributing factor to the formation of interpersonal dependence and depressive symptoms [36]. Furthermore, insecure attachment and low self-esteem may heighten feelings of insecurity about the relationship and could manifest as obsessive love; studies show that subjects involved in pathological love have lower levels of self-esteem and self-directedness than subjects with healthy relationships [31,37].

1.3. The Present Research

Given the aforementioned evidence, this research investigated the relationships between factors that may be associated with love addiction, focusing on adult attachment, and self-esteem. Therefore, the relationship between secure attachment, fearful attachment, preoccupied attachment, and dismissing attachment, and love addiction first were explored. Then, considering only the attachment styles showing a significant total effect, a path analysis was performed, hypothesizing that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Adult attachment patterns would be significantly associated with self-esteem.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Self-esteem would be significantly associated with love addiction.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Self-esteem would be a significant mediator in the relationship between adult attachment patterns and love addiction.

Since previous studies have shown the influence of age and gender on the considered variables [4,38,39], these factors were controlled as covariates to test the solidity of the interactions hypothesized in the model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

A sample group of 300 Italian individuals who declared themselves to have a romantic relationship was involved in this research (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample (N = 300).

Of the sample group, 42% were married, while 58% were only cohabiting. Their mean age was 37.83 years (SD = 12.937). Most of them were women (80%) and had a high school diploma (38%). They were recruited on the Internet through a snowball-like sampling method. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) having a romantic relationship; (2) being at least 18 years old. Each participant completed the survey online, through the Google Forms platform, after being briefed about the general aim of the research and providing informed consent electronically. Privacy and anonymity were guaranteed. All the procedures of this research were approved by the first author’s institutional ethical committee.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Love Addiction Inventory—Short Form (LAI—SF)

The Love Addiction Inventory—Short Form (LAI—SF) [40] is a 6-item self-report scale used for the assessment of the levels of love addiction, based on the components model of behavioural addiction [7]. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Higher scores indicate higher levels of love addiction symptoms. The original Italian 6-item version [40] was used in this research and showed an acceptable internal consistency in the present sample (α = 0.67).

2.2.2. Relationship Questionnaire (RQ)

The Relationship Questionnaire (RQ) [16,41] is a 4-item self-report scale used for the assessment of adult attachment patterns. Items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale, from 1 (“It does not describe me at all”) to 7 (“It very much describes me”) and allow for the assessment of secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful attachment styles. For each item, higher scores indicate higher levels of the corresponding attachment style. The Italian version was used in this research [41] and, since the four attachment styles are assessed with a single item, the alpha coefficient cannot be calculated. Nevertheless, RQ was found to have good test–retest reliability [42] and good psychometric properties in different cultures [43].

2.2.3. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES)

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) [44,45] is a 10-item self-report scale used for the assessment of the levels of global self-esteem. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale, from 0 (strongly agree) to 3 (strongly disagree). Higher scores indicate higher self-esteem. The total score of the Italian version was used in this research [45] and showed good internal consistency in the present sample (α = 0.84).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (v. 21.0; IBM, New York, NY, USA) and AMOS (v. 24.0; IBM, New York, NY, USA) for Windows. Pearson correlations were performed to explore the association among the variables of this research. Only the attachment patterns which were significantly associated with love addiction were included in the mediation model, which was implemented by using a path analysis [46], testing the mediation of self-esteem in the relationship between adult attachment and love addiction, controlling for the effects of gender (with males coded as “0” and females coded as “1”) and age as potential confounders. The statistical fit of the model was evaluated based on the following goodness-of-fit indicators: the discrepancy divided by degree of freedom (CMIN/DF), indicating a reasonable fit for values less than 5 [47]; the goodness of fit (GFI), indicating a reasonable fit for values above 0.90 [48]; the normed-fit index (NFI), indicating a reasonable fit for values above 0.90 [49]; and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), indicating a reasonable fit for values less than 0.08 [50]. The statistical stability and significance of the model was further investigated by performing the bootstrapping procedure for each of the 5000 bootstrapped samples with a 95% confidence interval [51].

3. Results

As shown in Table 2, love addiction was negatively and significantly correlated to self-esteem (r = 0.364, p < 0.01), and positively and significantly associated with preoccupied (r = 0.203, p < 0.01) and fearful (r = 0.256, p < 0.01) adult attachment.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix.

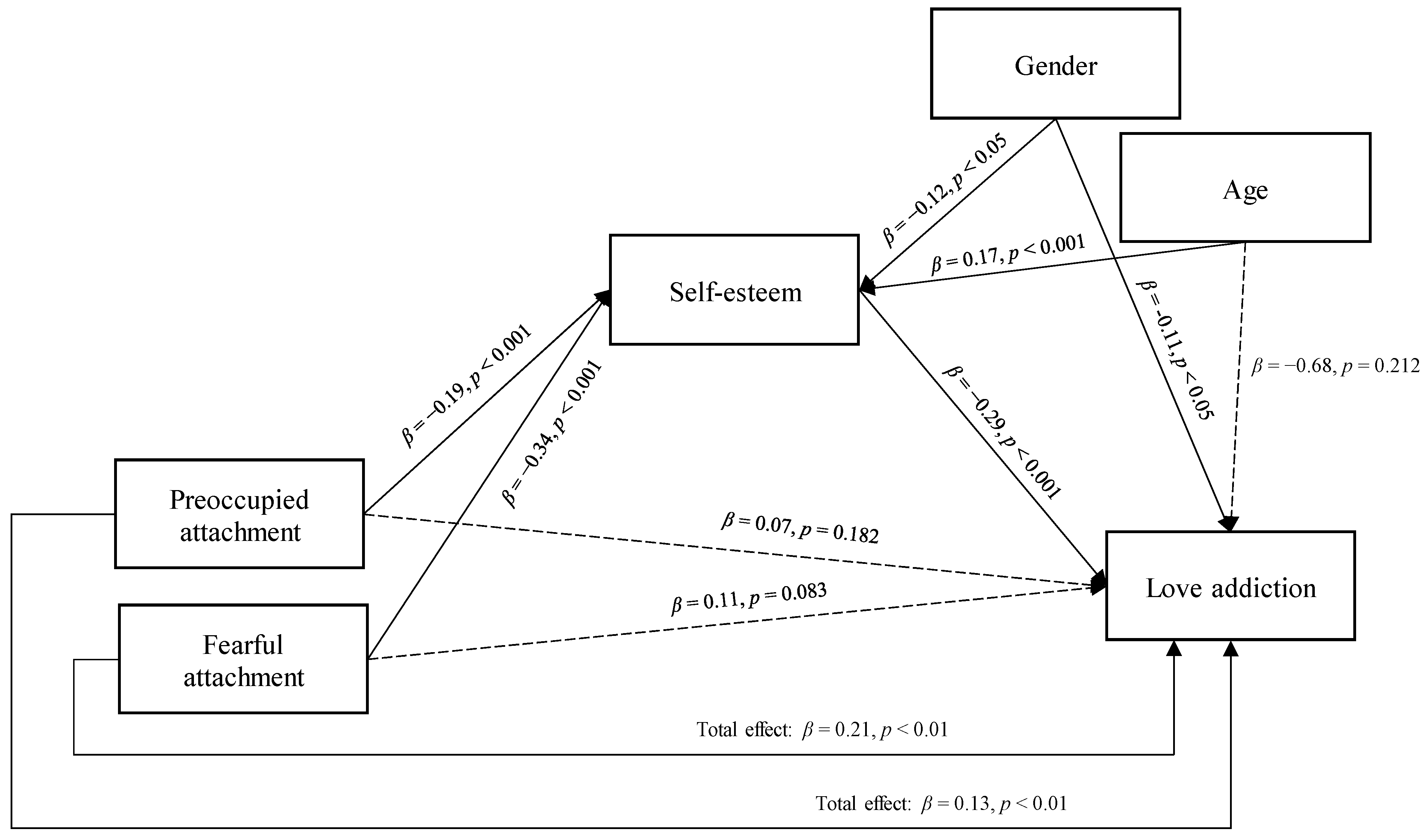

On that basis, a path analysis was implemented to test the mediation of self-esteem in the relationship between preoccupied and fearful adult attachment, and love addiction, controlling for the effects of gender and age (see Figure 1). The emerging mediation model showed a good fit, as follows: CMIN/DF = 4.501, GFI = 0.921, NFI = 0.907, and SRMR = 0.065.

Figure 1.

The mediation of self-esteem in the relationship between preoccupied and fearful adult attachment and love addiction, controlling for the effects of gender and age—a path analysis model. Note—dashed lines indicate the non-significant direct effects.

More specifically, preoccupied and fearful attachment patterns were significantly and negatively associated with self-esteem (β = −0.019, p < 0.001 and β = −0.34, p < 0.001, respectively; H1). In turn, self-esteem was significantly and negatively related to love addiction (β = −0.29, p < 0.001; H2). With regards to the covariates, while being female was associated with low levels of self-esteem (β = −0.12, p < 0.05) and high levels of love addiction (β = 0.11, p < 0.05), being older was related to higher levels of self-esteem (β = 0.17, p < 0.001), while no significant effects have been highlighted between age and love addiction in this model (p = 0.212). Finally, when included in the model, self-esteem totally mediated the effect of preoccupied and fearful attachment on love addiction, determining non-significant direct effects (β = 0.07, p = 0.182 and β = 0.11, p = 0.083, respectively, H3).

The bootstrapping procedure confirmed the statistical stability of the mediation model (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Coefficients of the structural equation mediation model.

4. Discussion

In recent years love addiction has become the subject of a strong interest within the scientific community. Recent studies show its similarity to other forms of addiction, such as substance dependence [52]. This data, based on behavioral, neurochemical, and neuroimaging evidence, underlines the importance of focusing on this type of addiction that is accompanied, due to its pervasive nature, by a strong negative impact on the life of those who suffer from it, including a high level of psychological suffering and loss of control. In fact, individuals with love addiction tend to experience negative mood and affective states when they are away from their partner and have the strong need and desire to see them deal with stressful situations [3,27]. Given the clinical relevance of the phenomena, the present study aimed at providing further knowledge on the psychological factors that may be associated with love addiction, by specifically focusing on adult attachment styles and self-esteem.

Concerning the relationship between love addiction and adult attachment, our results showed that only fearful and preoccupied styles showed significant and positive associations with love addiction. This is in line with earlier evidence showing how fearful and preoccupied attachments are associated with different forms of addiction; these two styles of attachment seem to be more frequent in subjects with substance dependence, such as with heroin [19], alcohol, tobacco, or waterpipes [53], as well as problematic smartphone use [54] and social media addiction [23,55], and sexual addiction [56]. The preoccupied attachment is characterized by fear that others are unavailable in times of need, and involves an anxious search for love and support and dependence on a desire for commitment in relationship, while fearful attachment is characterized by distrust of others’ intentions, compulsive self-reliance, and the low intensitiy of fewer love experiences [18,25]. Both arise from an attempt, in childhood, to adapt to a figure of attachment available in a way that is inconsistent or constantly unavailable. Such modalities become maladaptive when applied to later relationships, where the search for support and comfortable interdependence could be rewarding and help the person maintain a sense of well-being [18]. Such styles, both forms of anxious attachment [16,57], are associated with less satisfaction with the couple’s relationship, less sexual satisfaction, and the use of maladaptive coping mechanisms in the face of couple crises. An important pattern of anxious attachment is hyperactive attachment systems. In this case, a sensitive and hypervigilance position is activated in the relationship, and there might be appears some signs of obsessive love [26,58]. Fearful attachment is associated with a greater likelihood of separation or divorce, while preoccupied attachment is associated with greater difficulty in ending the relationship even in conditions of malaise [59,60,61,62,63].

Furthermore, our results also highlighted an indirect path in the relationship between fearful and preoccupied adult attachment styles and love addiction, through the mediation effect of self-esteem, confirming all the hypotheses (H1 to H3). More specifically, fearful and preoccupied attachment have been negatively associated with self-esteem (H1), as both of them are indeed characterized by a negative view of self, coupled with a negative and positive view of the other [16], which can result in lower levels of self-esteem. Consistently, the scientific literature shows that both preoccupied and fearful attachment styles are associated with lower levels of self-esteem than secure and dismissing attachment styles [33]; an anxious type of attachment would seem to be more associated, than the secure attachment style, with an unclear self-concept and more unstable self- esteem [30,31,64]. In turn, results shown a negative association between self-esteem and love addiction (H2), as low self-esteem can manifest itself in dysfunctional relational modes, also being a contributing factor to the formation of interpersonal dependence [36]. This is in line with previous studies that highlight associations between low self-esteem and low couple satisfaction, as individuals with low self-esteem believe that the partner sees them as they see themselves; therefore, to avoid disappointment, they tend to distance themselves. This leads to a reduction in couple satisfaction for both partners [65,66]. Moreover, this is in line with previous associations that highlight how low self-esteem is a risk factor for addictive behaviours, such as Internet, social media, and exercise addiction [34,35,67,68,69,70] and, more generally, is associated with lower levels of well-being, with more negative effects, fewer positive effects, and greater stress severity [71]. Therefore, the results of this study highlight that individuals with higher levels of fearful or preoccupied attachment, characterized by a negative self-view [16], tend to show lower levels of self-esteem which can result in dysfunctional relational modalities characterized by an excessive dependence on the partner [36] (H3).

Finally, the role of gender and age as potential confounders was controlled in testing the model. Focusing on gender, being female was associated with low levels of self-esteem and high levels of love addiction. This is in line with previous research showing how women tend to have lower self-esteem than men, especially for the domains of physical appearance, athleticism, personal self, and self-satisfaction [38,39,72]. Furthermore, this is consistent with previous research which highlighted the greater tendency in women than men to be addicted to love and relationships [4]. Concerning age, this factor did not show a direct effect on love addiction, while being younger was associated with lower levels of self-esteem. This could be read in relation to studies which highlight that self-esteem in young adults tends to be lower than in adulthood; in fact, instability and contingency of self-esteem decrease from adolescence to old age, whereas levels of self-esteem increase. Findings suggest that people’s self-esteem tends to become better adjusted (i.e., more stable, less contingent, and higher) across their life course [39,73]. In addition, young people seem to have less self-efficacy and less belief in their own potential for change, and generally report a lower level of well-being than older people [74,75,76].

The present study also has some limitations that should be highlighted. First, the study design was cross-sectional, and this requires caution in the interpretation of the causal link between the variables, as well as the directionality of these relationships. Therefore, although a solid basis of the scientific literature was used for the implementation of the model, it is also plausible that love addiction, in turn, influences self-esteem again, resulting in a vicious circle. Given this possibility, the replication of these results in longitudinal studies is needed in future research. Furthermore, the gender imbalance in the sample should be considered when interpreting the results. Although this issue was limited by controlling the effect of gender when testing the model, the use of more balanced samples could be an important challenge for future research. Finally, the use of self-report measures requires participants to be self-observing and willing to express aspects of themselves, exposing them to a variety of biases, e.g., the desirability bias. Although previous research on the scale employed here shows their good psychometric properties, theoretical foundation, and their excellent ability to discriminate the constructs, the use of a multi-method approach (e.g., integrating the assessment with interviews) could enrich the study and make future research more stable.

5. Conclusions

Given the negative and pervasive impact of love addiction in individuals’ lives [3], this research has focused on the variables that may be associated with this condition, providing information that can be useful to support and guide clinical practice. First, the results highlight the significant influence of fearful and preoccupied adult attachment styles. This data supports the possibility of directing the therapeutic work with subjects with love addiction on these factors, especially in the light of the broad line of research that highlights the effectiveness of clinical treatments in promoting changes in attachment patterns [77,78,79]. Furthermore, findings also showed the influence of self-esteem, which played a full mediator role in the model and presented negative associations with love addiction. This further corroborates the role of self-esteem in promoting mental health [80] and suggests the importance of focusing on this variable in both preventive and clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.; methodology, A.G.; formal analysis, A.G. and E.T.; investigation, A.G.; data curation, A.G. and E.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G., E.T. and S.R.; writing—review and editing, A.G., E.T. and S.R.; supervision, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Integrated Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Institute (IPPI; protocol code 011/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Salicetia, F. New addictions. Procedia Soc. 2015, 191, 1639–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Text Revision; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sanches, M.; John, V.P. Treatment of love addiction: Current status and perspectives. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2019, 33, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynaud, M.; Karila, L.; Blecha, L.; Benyamina, A. Is love passion an addictive disorder? Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2010, 36, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingiardi, V. Personalità dipendente e dipendenza relazionale. In Le Dipendenze Patologiche; Caretti, V., La Barbera, D., Eds.; Raffaello Cortina Editore: Milano, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta, G. Affective Dependence: From Pathological Affectivity to Personality Disorders: Definitions, Clinical Contexts, Neurobiological Profiles and Clinical Treatments. Health Sci. 2021, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J. Subst. Use 2005, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, R.F. The Dependent Personality; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Speranza, M.; Corcos, M.; Philippe, S.; Loas, G.; Perez-Diaz, F.; Lang, F.; Venisse, J.L.; Bizouard, P.; Flament, M.; Halfon, O.; et al. Alexithymia, depressive experiences, and dependency in addictive disorders. Subst Use Misuse 2004, 39, 551–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Donne Che si Fanno Male; Feltrinelli: Milano, Italy, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchad, M.E.; Yalch, K.L. Relationships among loneliness, interpersonal dependency, and disordered eating in young adults. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 46, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraley, C.R. Attachment in Adulthood: Recent Developments, Emerging Debates, and Future Directions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds. Br. J. Psychiatry 1977, 130, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillath, O.; Shaver, P.R.; Baek, J.M.; Chun, D.S. Genetic correlates of adult attachment style. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 1396–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.; Horowitz, L.M. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Attachment orientations and emotion regulation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 25, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, A. Attachment and substance use disorders—Theoretical models, empirical evidence, and implications for treatment. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gori, A.; Topino, E.; Cacioppo, M.; Craparo, G.; Schimmenti, A.; Caretti, V. An addictive disorders severity model: A chained mediation analysis using structural equation modeling. J. Addict. Dis. 2022, 41, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A.; Topino, E.; Craparo, G.; Bagnoli, I.; Caretti, V.; Schimmenti, A. A comprehensive model for gambling behaviors: Assessment of the factors that can contribute to the vulnerability and maintenance of gambling disorder. J. Gambl. Stud. 2022, 38, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topino, E.; Cacioppo, M.; Gori, A. The Relationship between Attachment Styles and Compulsive Online Shopping: The Mediating Roles of Family Functioning Patterns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arienzo, M.C.; Boursier, V.; Griffiths, M.D. Addiction to Social Media and Attachment Styles: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019, 17, 1094–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, R.; Blue Star, J.; Hansen, B.; Carpenter, B. Relationship attachment styles in a sample of hypersexual patients. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2015, 41, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, V.; Davoudi, I.; Ghazaei, M.; Mardani, M.; Seifi, S. Prevalence of Obsessive Love and Its Association with Attachment Styles. Procedia Soc. 2013, 84, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Honari, B.; Saremi, A.A. The study of relationship between attachment styles and obsessive love style. Procedia Soc. 2015, 165, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S. Love Addiction: Definition, Etiology, Treatment. Sex Addict. Compulsivity 2010, 17, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghi, F.; Pallini, S. Valutazione dell’autostima e caratteristiche di personalità in adolescenza. G. Ital. Psicol. 2008, 35, 679–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, M.; Di Fabio, A.; Gori, A. Measuring the Self-Esteem: Applying the Mixed Rasch Model to the Self-Esteem Scale (SES). Riv. Psicol. Del Lav. E Dell’organizzazione 2007, 13, 359–371. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto, T. The moderating role of attachment style on the relationship between self-concept clarity and self-esteem. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 152, 109604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H. The relationship between attachment style and self-concept clarity: The mediation effect of self-esteem. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 47, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, B.P.; Aron, A. Does a long-term relationship kill romantic love? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2009, 13, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylsma, W.H.; Cozzarelli, C.; Sumer, N. Relation between adult attachment styles and global self-esteem. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydm, B.; San, S.V. Internet addiction among adolescents: The role of self-esteem. Procedia Soc. 2011, 15, 3500–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrainian, S.A.; Alizadeh, K.H.; Raeisoon, M.R.; Gorji, O.H.; Khazaee, A. Relationship of Internet addiction with self-esteem and depression in university students. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2014, 55, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagishi, Y.; Sakata, M.; Kitamura, T. Effects of Self-Esteem on State and Trait Components of Interpersonal Dependency and Depression in the Workplace. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sophia, E.C.; Tavares, H.; Berti, M.P.; Pereira, A.P.; Lorena, A.; Mello, C.; Zilberman, M.L. Pathological Love: Impulsivity, Personality, and Romantic Relationship. CNS Spectr. 2009, 14, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, M.; Li, C.; Hall, J.A. When men and women differ in self-esteem and when they don’t: A meta-analysis. J. Res. Pers. 2016, 64, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleidorn, W.; Arslan, R.C.; Denissen, J.J.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Gebauer, J.E.; Potter, J.; Gosling, S.D. Age and gender differences in self-esteem—A cross-cultural window. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 2016, 111, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Barberis, N.; Griffiths, M.D.; Benedetto, L.; Ingrassia, M. The love addiction inventory: Preliminary findings of the development process and psychometric characteristics. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, L. Attaccamento e Rapporto di Coppia; Raffaello Cortina: Milano, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ligiéro, D.P.; Gelso, C.J. Countertransference, attachment, and the working alliance: The therapist’s contribution. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2002, 39, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, D.P.; Alcalay, L.; Allensworth, M.; Allik, J.; Ault, L.; Austers, I.; Bennett, K.; Bianchi, G.; Boholst, F.; Cunen, M.A.B. Patterns and universals of adult romantic attachment across 62 cultural regions: Are models of self and of other pancultural constructs? J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2004, 35, 367–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Accept. Commit. Ther. Meas. Package 1965, 61, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Prezza, M.; Trombaccia, F.R.; Armento, L. La scala dell’autostima di Rosenberg: Traduzione e validazione Italiana [The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Italian translation and validation]. Giunti Organ. Spec. 1997, 223, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A.; Long, J.S. Testing Structural Equation Models; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; Volume 154. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hocevar, D. Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First- and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 97, 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.-H.R. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol. Methods 2022, 7, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; MacCallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earp, B.D.; Wudarczyk, O.A.; Foddy, B.; Savulescu, J. Addicted to love: What is love addiction and when should it be treated? Philos. Psychiatry Psychol. 2017, 24, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakhoul, L.; Obeid, S.; Sacre, H.; Haddad, C.; Soufia, M.; Hallit, R.; Akel, M.; Salameh, P.; Hallit, S. Attachment style and addictions (alcohol, cigarette, waterpipe and internet) among Lebanese adolescents: A national study. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Xie, F.; Chen, X.; Xu, W.; Hudson, N.W. The relationship between adult attachment and mental health: A meta-analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 123, 1089–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A.; Topino, E. The Association between Alexithymia and Social Media Addiction: Exploring the Role of Dysmorphic Symptoms, Symptoms Interference, and Self-Esteem, Controlling for Age and Gender. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, J.L.; Greiner, J.; Carroll, J. Attachment styles and male sex addiction. Sex Addict. Compulsivity 2008, 15, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research. Addict. Behav. 2021, 114, 106699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. An attachment perspective on psychopathology. World Psychiatry 2012, 11, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, G.E.; Orr, I.; Mikulincer, M.; Florian, V. When Marriage Breaks Up-Does Attachment Style Contribute to Coping and Mental Health? J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1997, 14, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banse, R. Adult attachment and marital satisfaction: Evidence for dyadic configuration effects. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2004, 21, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzer, B.; Campbell, L. Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Pers. Relatsh. 2008, 15, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candel, O.S.; Turliuc, M.N. Insecure attachment and relationship satisfaction: A meta-analysis of actor and partner associations. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 147, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favez, N.; Tissot, H. Fearful-avoidant attachment: A specific impact on sexuality? J. Sex Marital Ther. 2019, 45, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, J.D.; Kernis, M.H.; Goldman, B.M. Linking Adult Attachment of Self-Esteem Stability. Self Identity 2007, 6, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, R.Y.; Orth, U. Self-esteem and the quality of romantic relationships. Eur. Psychol. 2017, 21, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghaziri, N.; Darwiche, J. Adult self-esteem and family relationships. Swiss J. Psychol. 2018, 77, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A.; Topino, E.; Griffiths, M.D. Protective and risk factors in exercise addiction: A series of moderated mediation analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021, 18, 9706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A.; Topino, E.; Pucci, C.; Griffiths, M.D. The Relationship between Alexithymia, Dysmorphic Concern, and Exercise Addiction: The Moderating Effect of Self-Esteem. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błachnio, A.; Przepiorka, A.; Pantic, I. Association between Facebook addiction, self-esteem and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, H.R. The role of self-esteem in tendency towards drugs, theft and prostitution. Addict Health 2011, 3, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Juth, V.; Smyth, J.M.; Santuzzi, A.M. How do you feel? Self-esteem predicts affect, stress, social interaction, and symptom severity during daily life in patients with chronic illness. J. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, B.; Grabe, S.; Dolan-Pascoe, B.; Twenge, J.M.; Wells, B.E.; Maitino, A. Gender differences in domain-specific self-esteem: A meta-analysis. Rev. Gen. Psychol 2009, 13, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, L.L.; Orth, U.; Denissen, J.J.; Kühnel, A. Age differences in instability, contingency, and level of self-esteem across the life span. J. Res. Pers. 2011, 45, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albion, M.J.; Fernie, L.J. Individual differences in age and self-efficacy in the unemployed. Aust. J. Psychol. 2005, 57, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruine de Bruin, W.; Parker, A.M.; Strough, J. Age differences in reported social networks and well-being. Psychol Aging 2020, 35, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, J.R.; Charles, S.T.; Almeida, D.M. Living with chronic health conditions: Age differences in affective well-being. J. Gerontol B Psychol Sci. Soc. Sci. 2007, 62, P313–P321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Rietzschel, J.; Danquah, A.; Berry, K. Changes in attachment representations during psychological therapy. Psychother Res. 2015, 25, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmarosh, C.L.; Tasca, G.A. Adult attachment anxiety: Using group therapy to promote change. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 69, 1172–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, K.N.; Meehan, K.B.; Kelly, K.M.; Reynoso, J.S.; Weber, M.; Clarkin, J.F.; Kernberg, O.F. Change in attachment patterns and reflective function in a randomized control trial of transference-focused psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. J. Consult. Psychol. 2006, 74, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A. Self, identity, stress, and mental health. In Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 357–377. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).