Validation of Pharmacogenomic Interaction Probability (PIP) Scores in Predicting Drug–Gene, Drug–Drug–Gene, and Drug–Gene–Gene Interaction Risks in a Large Patient Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

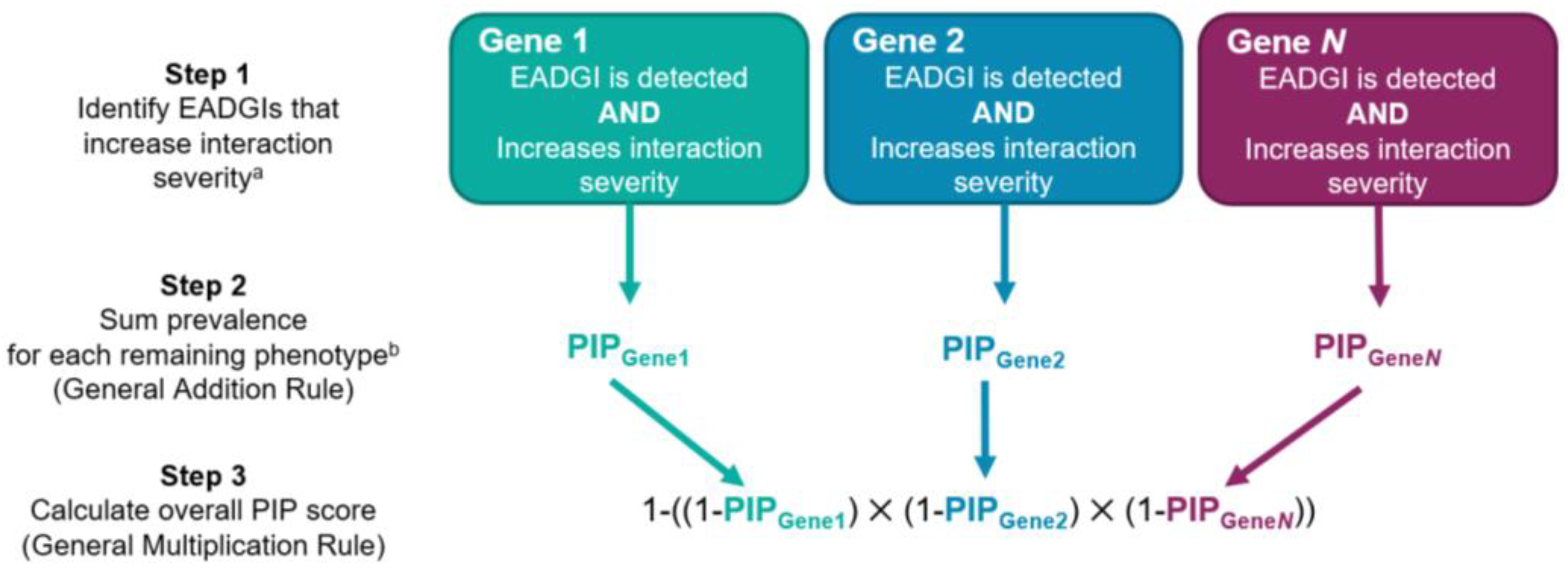

2.2. YouScript Algorithm: Pharmacogenomic Interaction Probability

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Study Population

3.2. Comparison of PIP Scores to PGx Test Results

3.3. Characterization of All Interactions

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swalwell, E.H.R. 6875—Right Drug Dose Now Act. 117th Congress (2021–2022). Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/6875?s=1&r=47 (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labeling. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/science-and-research-drugs/table-pharmacogenomic-biomarkers-drug-labeling (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Genes-Drugs. Available online: https://cpicpgx.org/genes-drugs/ (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Kim, J.A.; Ceccarelli, R.; Lu, C.Y. Pharmacogenomic biomarkers in US FDA-approved drug labels (2000–2020). J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polasek, T.M.; Kirkpatrick, C.M.J.; Rostami-Hodjegan, A. Precision dosing to avoid adverse drug reactions. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2019, 10, 2042098619894147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, J.D.; Dalton, R.; Elchynski, A.L.; Smith, D.M.; Cicali, E.J.; Lee, J.C.; Duong, B.Q.; Petry, N.J.; Aquilante, C.L.; Beitelshees, A.L.; et al. Multisite investigation of strategies for the clinical implementation of pre-emptive pharmacogenetic testing. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 2335–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oslin, D.W.; Lynch, K.G.; Shih, M.-C.; Ingram, E.P.; Wray, L.O.; Chapman, S.R.; Kranzler, H.R.; Gelernter, J.; Pyne, J.M.; Stone, A.; et al. Effect of pharmacogenomic testing for drug-gene interactions on medication selection and remission of symptoms in major depressive disorder: The PRIME Care Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022, 328, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanfreau-Coffinier, C.; Hull, L.E.; Lynch, J.A.; DuVall, S.L.; Damrauer, S.M.; Cunningham, F.E.; Voight, B.F.; Matheny, M.E.; Oslin, D.W.; Icardi, M.S.; et al. Projected prevalence of actionable pharmacogenetic variants and level A drugs prescribed among US Veterans Health Administration pharmacy users. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e195345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Skierka, J.M.; Blommel, J.H.; Moore, B.E.; VanCuyk, D.L.; Bruflat, J.K.; Peterson, L.M.; Veldhuizen, T.L.; Fadra, N.; Peterson, S.E.; et al. Preemptive pharmacogenomic testing for precision medicine: A comprehensive analysis of five actionable pharmacogenomic genes using next-generation DNA sequencing an a customized CYP2D6 genotyping cascade. J. Mol. Diagn. 2016, 18, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzel, K.W.; Cavallari, L.H.; Lesko, L.J. Preemptive panel-based pharmacogenetic testing: The time is now. Pharm. Res. 2017, 34, 1551–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brixner, D.; Biltaji, E.; Bress, A.; Unni, S.; Ye, X.; Mamiya, T.; Ashcraft, K.; Biskupiak, J. The effect of pharmacogenetic profiling with a clinical decision support tool on healthcare resource utilization and estimated costs in the elderly exposed to polypharmacy. J. Med. Econ. 2016, 19, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.K.; Pierce, D.L.; Weitendorf, F.; Linder, M.W. Avoidable drug–gene conflicts and polypharmacy interactions in patients participating in a personalized medicine program. Per. Med. 2017, 14, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, L.S.; Henderson, J.C.; Neradilek, M.B.; Moyer, N.A.; Ashcraft, K.C.; Thirumaran, R.K. Clinical impact of pharmacogenetic profiling with a clinical decision support tool in polypharmacy home health patients: A prospective pilot randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, H.C.; Patterson, R.D.; Oesterheld, J.; Pany, R.V.; Ashcraft, K. Systems and Methods for Quantification and Presentation of Medical Risk Arising from Unknown Factors. US Patent 10,210,312, 19 February 2019. 11,302,243, 12 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Grande, K.J.; Dalton, R.; Moyer, N.A.; Arwood, M.J.; Nguyen, K.A.; Sumfest, J.; Ashcraft, K.C.; Cooper-DeHoff, R.M. Assessment of a manual method versus an automated, probability-based algorithm to identify patients at high risk for pharmacogenomic adverse drug outcomes in a university-based health insurance program. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcraft, K.; Moretz, C.; Schenning, C.; Rojahn, S.; Vines Tanudtanud, K.; Magoncia, G.O.; Reyes, J.; Marquez, B.; Guo, Y.; Erdemir, E.T.; et al. Unmanaged pharmacogenomic and drug interaction risk associations with hospital length of stay among Medicare Advantage members with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/atc-ddd-toolkit/atc-classification (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Epitools Epidemiological Calculators. Available online: https://epitools.ausvet.com.au/ztestone (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- The Top 200 of 2019. Available online: https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top200Drugs.aspx (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- David, V.; Fylan, B.; Bryant, E.; Smith, H.; Sagoo, G.S.; Rattray, M. An Analysis of pharmacogenomic-guided pathways and their effect on medication changes and hospital admissions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 698148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, G.; Lavertu, A.; Sangkuhl, K.; Klein, T.E.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Altman, R.B. Pharmacogenetics at scale: An analysis of the UK Biobank. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 109, 1528–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildcrout, J.S.; Denny, J.C.; Bowton, E.; Gregg, W.; Pulley, J.M.; Basford, M.A.; Cowan, J.D.; Xu, H.; Ramirez, A.H.; Crawford, D.C.; et al. Optimizing drug outcomes through pharmacogenetics: A case for preemptive genotyping. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 92, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halverson, C.M.; Pratt, V.M.; Skaar, T.C.; Schwartz, P.H. Ending the pharmacogenomic gag rule: The imperative to report all results. Pharmacogenomics 2021, 22, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahikainen, A.-L.; Vauhkonen, P.; Pett, H.; Palo, J.U.; Haukka, J.; Ojanperä, I.; Niemi, M.; Sajantila, A. Completed suicides of citalopram users-the role of CYP genotypes and adverse drug interactions. Int. J. Legal Med. 2019, 133, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, L.S.; Ishtiak-Ahmed, K.; Thirstrup, J.P.; Agerbo, E.; Lunenburg, C.A.T.C.; Müller, D.J.; Gasse, C. Clinical impact of functional CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 gene variants on treatment with antidepressants in young people with depression: A Danish cohort study. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statins Given for 5 Years for Heart Disease Prevention (With Known Heart Disease). Available online: https://www.thennt.com/nnt/statins-for-heart-disease-prevention-with-known-heart-disease/ (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- FDA Drug Safety Communication: Reduced Effectiveness of Plavix (clopidogrel) in Patients Who Are Poor Metabolizers of the Drug. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/fda-drug-safety-communication-reduced-effectiveness-plavix-clopidogrel-patients-who-are-poor (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Ongoing Emergencies & Disasters. Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/Emergency/EPRO/Current-Emergencies/Ongoing-emergencies (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Crews, K.R.; Monte, A.A.; Huddart, R.; Caudle, K.E.; Kharasch, E.D.; Gaedigk, A.; Dunnenberger, H.M.; Leeder, J.S.; Callaghan, J.T.; Samer, C.F.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guideline for CYP2D6, OPRM1, and COMT genotypes and select opioid therapy. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 110, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crist, R.C.; Li, J.; Doyle, G.A.; Gilbert, A.; Dechairo, B.M.; Berrettini, W.H. Pharmacogenetic analysis of opioid dependence treatment dose and dropout rate. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2018, 44, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, A.B.; Braakman, M.H.; Vinkers, D.J.; Hoek, H.W.; van Harten, P.N. Meta-analysis of probability estimates of worldwide variation of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vowles, K.E.; McEntee, M.L.; Julnes, P.S.; Frohe, T.; Ney, J.P.; van der Goes, D.N. Rates of opioid Misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: A systematic review and data synthesis. Pain 2015, 156, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, R.R.; Smith, R.L. Addressing phenoconversion: The Achilles’ heel of personalized medicine. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 79, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, M.; Roll, S.C. The influence of pharmacogenetics on the clinical relevance of pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions: Drug-gene, drug-gene-gene and drug-drug-gene interactions. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagec, K.; Kuch, W.; Samwald, M. The importance of gene-drug-drug-interactions in pharmacogenomics decision support: An analysis based on Austrian claims data. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2017, 236, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, S.; Polasek, T.M.; Sheffield, L.J.; Huppert, D.; Kirkpatrick, C.M.J. Quantifying the impact of phenoconversion on medications with actionable pharmacogenomic guideline recommendations in an acute aged persons mental health setting. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 724170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, A.K. Potential role for pharmacogenomic testing in combating opioid epidemic. Curbside Consult 2022, 20, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Borse, M.S.; Dong, O.M.; Polasek, M.J.; Farley, J.F.; Stouffer, G.A.; Lee, C.R. CYP2C19-Guided Antiplatelet Therapy: A cost-effectiveness analysis of 30-day and 1-year outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention. Pharmacogenomics 2017, 18, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What’s the Least Expensive Cholesterol Medication in 2021? Available online: https://www.talktomira.com/post/how-much-do-statins-cost-without-insurance (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Statin Therapy for the Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease. Available online: https://ecqi.healthit.gov/ecqm/ec/2022/cms347v5#quicktabs-tab-tabs_measure-0 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Statin Therapy for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes (SPC/SPD). National Committee for Quality Assurance. Available online: https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/statin-therapy-for-patients-with-cardiovascular-disease-and-diabetes/ (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Carta, A.; Del Zompo, M.; Meloni, A.; Mola, F.; Paribello, P.; Pinna, F.; Pinna, M.; Pisanu, C.; Manchia, M.; Squassina, A.; et al. Cost-utility analysis of pharmacogenetic testing based on CYP2C19 or CYP2D6 in major depressive disorder: Assessing the drivers of different cost-effectiveness levels from an Italian societal perspective. Clin. Drug Investig. 2022, 42, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.R.; Garrison, L.P., Jr.; Doyle, D.L.; Jarvik, G.P.; Watkins, J.; Devine, B. Projected cost-effectiveness for 2 gene-drug pairs using a multigene panel for patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Value Health 2019, 22, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Dangers of Polypharmacy and the Case for Deprescribing in Older Adults. National Institute on Aging. Available online: https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/dangers-polypharmacy-and-case-deprescribing-older-adults (accessed on 27 May 2022).

| Minimum No. of Genes in Panel | 3 (All Study Patients) | 5 | 14 | 25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Genes Included in Panel | CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6 | CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5 | CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP2B6, CYP4F2, SLCO1B1, TPMT, DPYD, HLA-B*57:01, IFNL3, UGT1A1, VKORC1 | CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, ADRA2A, COMT, CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP4F2, DPYD, F2, F5, GRIK4, HLA-B*57:01, HTR2A, HTR2C, IFNL3, MTHFR, NAT2, OPRM1, SLCO1B1, TPMT, UGT1A1, VKORC1 |

| No. of Patients | 36,511 | 28,613 | 3192 | 2068 |

| Mean Age, years * | 61 | 61 | 60 | 53 |

| Age Range, years *,** | 0–110 | 0–110 | 0–101 | 0–95 |

| No. of Patients ≥ 65 years (%) | 18,124 (49.6) | 14,603 (51.0) | 1721 (53.9) | 758 (36.7) |

| Sex *, No. (%) | ||||

| Female | 20,554 (56.3) | 16,298 (57.0) | 1674 (52.4) | 1075 (52.0) |

| Male | 14,360 (39.3) | 10,995 (38.4) | 1215 (38.1) | 691 (33.4) |

| Unknown | 1597 (4.4) | 1320 (4.6) | 303 (9.5) | 302 (14.6) |

| Race *, No. (%) | ||||

| Black | 2968 (8.1) | 2478 (8.7) | 44 (1.4) | 44 (2.1) |

| Asian | 387 (1.1) | 346 (1.2) | 14 (.4) | 14 (0.7) |

| White | 17,215 (47.2) | 13,339 (46.6) | 614 (19.2) | 612 (29.6) |

| Hispanic | 3413 (9.3) | 2520 (8.8) | 74 (2.3) | 72 (3.5) |

| Jewish (Ashkenazi) | 145 (0.4) | 120 (0.4) | 4 (0.1) | 4 (0.2) |

| Unknown | 12,383 (33.9) | 9810 (34.3) | 2442 (76.5) | 1322 (63.9) |

| Mean No. of Medications per Patient (Range) | 9.4 (1–62) | 9.8 (1–62) | 9.5 (1–62) | 9.0 (1–62) |

| Mean No. of Variants or Variant Phenotypes per Patient | 4.0 | 3.6 | 10.4 | 10.8 |

| ≥1 Variant or Variant Phenotype, % | 96.9 | 97.7 | 100 | 100 |

| Minimum No. of Genes Tested | No. of Patients | Mean PIP Score (25 Genes) | Mean Adjusted PIP Score * (to Minimum Genes Tested per Patient) | EADGI Rate ** (No. of Patients with at Least One EADGI) | NNT | p-Value (Mean Adjusted PIP Score vs. % EADGIs Detected) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 36,511 | 26.4% | 22.4% | 22.4% (8174) | 4.5 | 1.0000 |

| 5 | 28,613 | 27.5% | 23.5% | 23.4% (6707) | 4.3 | 0.6895 |

| 14 | 3192 | 31.0% | 30.9% | 29.4% (937) | 3.4 | 0.0667 |

| 25 | 2068 | 27.4% | 27.3% | 26.4% (545) | 3.8 | 0.3583 |

| Clinical Area | No. (%) of Moderate EADGIs (n = 7360) | No. (%) of Major or Contraindicated EADGIs (n = 2444) | No. (%) of All EADGIs (Moderate, Major, Contraindicated) (n = 9804) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Health | 765 (10.4) | 1106 (45.3) | 1871 (19.1) |

| Cardiology | 3230 (43.9) | 877 (35.9) | 4107 (41.9) |

| Pain Management | 470 (6.4) | 456 (18.7) | 926 (9.4) |

| Hematology and Oncology | 37 (0.5) | 3 (0.1) | 40 (0.4) |

| Infectious Disease | 0 | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.0) |

| Gastroenterology | 2634 (35.8) | 0 | 2634 (26.9) |

| Urology | 108 (1.5) | 0 | 108 (1.1) |

| Transplant | 8 (0.1) | 0 | 8 (0.1) |

| Reproductive and Sexual Health | 16 (0.2) | 0 | 16 (0.2) |

| Neurology | 42 (0.6) | 0 | 42 (0.4) |

| Rheumatology | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Endocrinology | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Miscellaneous | 50 (0.7) | 0 | 50 (0.5) |

| Affected Drug | Gene | Drug 2 | AUC Change: Affected Drug + − Gene | AUC Change: Affected Drug + − Drug 2 | Estimated AUC Change: Affected Drug + Gene + Drug 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| clopidogrel (metabolite) | CYP2C19 Intermediate Metabolizer | tramadol | −31–50% | −31–50% | −51–80% |

| citalopram | CYP2C19 Rapid Metabolizer | esomeprazole | −31–50% | 26–75% | −0–30% |

| clopidogrel (metabolite) | CYP2C19 Intermediate Metabolizer | oxycodone | −31–50% | −31–50% | −51–80% |

| amitriptyline | CYP2D6 Intermediate Metabolizer | bupropion | 26–75% | 26–75% | 76–200% |

| clopidogrel (metabolite) | CYP2C19 Intermediate Metabolizer | morphine | −31–50% | −31–50% | −51–80% |

| metoprolol | CYP2D6 Intermediate Metabolizer | dronedarone | 76–200% | 26–75% | >200% |

| clopidogrel (metabolite) | CYP2C19 Intermediate Metabolizer | hydrocodone | −31–50% | −31–50% | −51–80% |

| clopidogrel (metabolite) | CYP2C19 Poor Metabolizer | tramadol | −51–80% | −31–50% | −81–100% |

| amitriptyline | CYP2D6 Poor Metabolizer | bupropion | 76–200% | 26–75% | >200% |

| citalopram | CYP2C19 Rapid Metabolizer | fluvoxamine | −31–50% | 26–75% | −0–30% |

| Drug (Clinical Area) | No. of Moderate EADGIs | Proportion of All EADGIs | Medication PIP Score | NNT | Rank among Top 200 Most Commonly Prescribed * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| metoprolol (Cardiology) | 2852 | 29.1% | 48% | 2.1 | 5 |

| omeprazole (Gastroenterology) | 1673 | 17.1% | 29% | 3.4 | 8 |

| es(citalopram) (Behavioral Health) | 1038 | 10.6% | 32% | 3.1 | 19, 30 (10 combined) |

| clopidogrel (Cardiology) | 872 | 8.9% | 29% | 3.4 | 36 |

| pantoprazole (Gastroenterology) | 635 | 6.5% | 29% | 3.4 | 16 |

| Drug (Clinical Area) | No. of EADGIs | Proportion of Major or Contraindicated EADGIs | Medication PIP Score | NNT | Rank among Top 200 Most Commonly Prescribed * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| es (citalopram) (Behavioral Health) | 966 | 39.5% | 32% | 3.1 | 19, 30 (10 combined) |

| clopidogrel (Cardiology) | 873 | 35.7% | 29% | 3.4 | 36 |

| Tramadol (Pain Management) | 305 | 12.5% | 9% | 11.1 | 35 |

| codeine (Pain Management) | 98 | 4.0% | 9% | 11.1 | 173 |

| amitriptyline (Behavioral Health) | 76 | 3.1% | 50% | 2.0 | 94 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ashcraft, K.; Grande, K.; Bristow, S.L.; Moyer, N.; Schmidlen, T.; Moretz, C.; Wick, J.A.; Blaxall, B.C. Validation of Pharmacogenomic Interaction Probability (PIP) Scores in Predicting Drug–Gene, Drug–Drug–Gene, and Drug–Gene–Gene Interaction Risks in a Large Patient Population. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1972. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12121972

Ashcraft K, Grande K, Bristow SL, Moyer N, Schmidlen T, Moretz C, Wick JA, Blaxall BC. Validation of Pharmacogenomic Interaction Probability (PIP) Scores in Predicting Drug–Gene, Drug–Drug–Gene, and Drug–Gene–Gene Interaction Risks in a Large Patient Population. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022; 12(12):1972. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12121972

Chicago/Turabian StyleAshcraft, Kristine, Kendra Grande, Sara L. Bristow, Nicolas Moyer, Tara Schmidlen, Chad Moretz, Jennifer A. Wick, and Burns C. Blaxall. 2022. "Validation of Pharmacogenomic Interaction Probability (PIP) Scores in Predicting Drug–Gene, Drug–Drug–Gene, and Drug–Gene–Gene Interaction Risks in a Large Patient Population" Journal of Personalized Medicine 12, no. 12: 1972. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12121972

APA StyleAshcraft, K., Grande, K., Bristow, S. L., Moyer, N., Schmidlen, T., Moretz, C., Wick, J. A., & Blaxall, B. C. (2022). Validation of Pharmacogenomic Interaction Probability (PIP) Scores in Predicting Drug–Gene, Drug–Drug–Gene, and Drug–Gene–Gene Interaction Risks in a Large Patient Population. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(12), 1972. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12121972