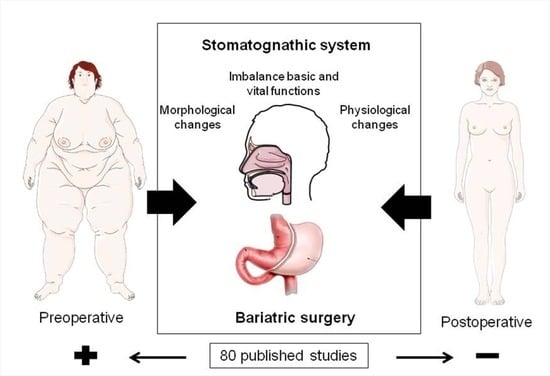

Stomatognathic System Changes in Obese Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Question

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Overweight subjects, those with obesity or morbid obesity, or those who had undergone bariatric surgery

- A publication time window of 10 years;

- Articles focused on the evaluation of aspects related to the distal airways, upper airways, lower airways, stomatognathic system (morphology and physiology), respiratory system, masticatory system, and swallowing mechanics;

- Studies conducted with humans;

- Full-text articles;

- Free-access articles and current DOIs.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Articles with DOIs that were not current within the databases for download;

- Research with a time window of >10 years;

- Articles that were not related to human beings;

- Grey literature, such as theses, white books, research and project reports, annual or activity reports, conference proceedings, preprints, working papers, newsletters, technical reports, recommendations and technical standards, patents, technical notes, data and statistics, presentations, field notes, laboratory research books, abstracts, academic courseware, lecture notes, and evaluations, were excluded.

2.2. Sources of Information

2.2.1. Search Strategies

2.2.2. Characteristics of the Studies

2.3. Selection and Analysis

3. Results

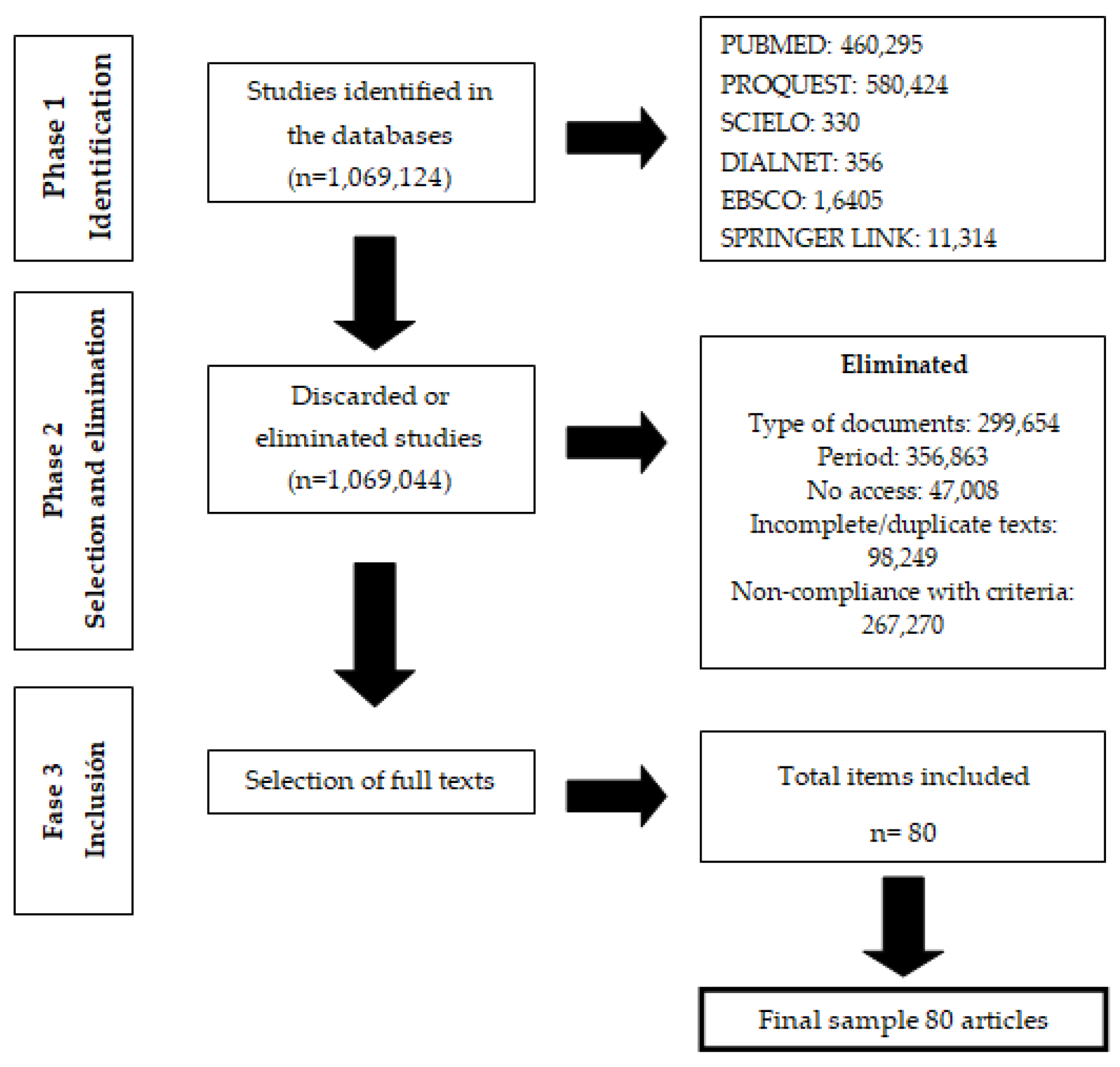

3.1. Identification Phase

3.2. Selection and Elimination Phase

3.3. Inclusion Phase

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barreto, J.F. Sistema estomatognático y esquema corporal. Colomb. Méd. 1999, 30, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, L.; Carlsson, J.; Jenneborg, K.; Kjaeldgaard, M. Perceived oral health in patients after bariatric surgery using oral health-related quality of life measures. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2018, 4, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nettle, D.; Andrews, C.; Bateson, M. Food insecurity as a driver of obesity in humans: The insurance hypothesis. Behav. Brain Sci. 2017, 40, e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Globus, I.; Kissileff, H.R.; Hamm, J.D.; Herzog, M.; Mitchell, J.E.; Latzer, Y. Comparison of interview to questionnaire for assessment of eating disorders after bariatric surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena, E. Obesidad un Factor de Riesgo en el COVID-19; Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Camhi, S.M.; Must, A.; Gona, P.N.; Hankinson, A.; Odegaard, A.; Reis, J.; Gunderson, E.P.; Jacobs, D.R.; Carnethon, M.R. Duration and stability of metabolically healthy obesity over 30 years. Int. J. Obes. 2019, 43, 1803–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzo, A.; Gratteri, S.; Gualtieri, P.; Cammarano, A.; Bertucci, P.; Di Renzo, L. Why primary obesity is a disease? J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malo Serrano, M.; Castillo, N.; Pajita, D. La obesidad en el mundo. Anal. Fac. Med. 2017, 78, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.H.T.; Peters, U.; Daphtary, N.; MacLean, E.S.; Hodgdon, K.; Kaminsky, D.A.; Bhatawadekar, S.; Dixon, A.E. Altered airway mechanics in the context of obesity and asthma. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 130, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, P.; Souki, A.; Arráiz Rodríguez, N.J.; Prieto Fuenmayor, C.; Cano-Ponce, C.; Acosta Martínez, J.; Chávez Castillo, M.; Sánchez, M.E.; Anderson Vásquez, H.E.; Plua Marcillo, W.; et al. Aspectos Básicos en Obesidad; Ediciones Universidad Simón Bolívar: Barranquilla, Colombia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, A.L.F.; Salgado, W.; Dantas, O. Maximum phonation time in people with obesity not submitted or submitted to bariatric surgery. J. Obes. 2019, 2019, 5903621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasini, K.; Ziegler, B.; Sanchez, P.R.S.; da Silva Junior, D.P.; Thomé, P.R.; Dalcin, P.T.R. Dyspnea perception during the inspiratory resistive loads test in obese subjects waiting bariatric surgery. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpio, C.; Santiago, A.; García de Lorenzo, A.; Álvarez-Sala, R. Función pulmonar y obesidad. Nutr. Hosp. 2014, 30, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mashaqi, S.; Steffen, K.; Crosby, R.; Garcia, L. The impact of bariatric surgery on sleep disordered breathing parameters from overnight polysomnography and home sleep apnea test. Cureus 2018, 10, e2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor Taba, J.; Oliveira Suzuki, M.; do Nascimento, F.S.; Ryuchi Iuamoto, L.; Hsing, W.T.; Zumerkorn Pipek, L.; Andraus, W. The development of feeding and eating disorders after bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzerouk, F.; Djerada, Z.; Bertin, E.; Barrière, S.; Gierski, F.; Kaladjian, A. Contributions of emotional overload, emotion dysregulation, and impulsivity to eating patterns in obese patients with binge eating disorder and seeking bariatric surgery. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluenda, G.F. Cirugía bariátrica. Rev. Med. Clin. Condes 2012, 23, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro, C.A.; Funk, G.D.; Feldman, J.L. Breathing matters. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 19, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade Rocha, A.C.; De Souza Conceição, N.O.; Mangili Toni, L.D. Chewing and swallowing in obese individuals referred to bariatric surgery/gastroplasty—A pilot study. Rev. CEFAC 2021, 221, e8519. [Google Scholar]

- Crummy, A.; Piper, A.; Naughton, M.T. Obesity and the lung: 2·Obesity and sleep-disordered breathing. Thorax 2008, 63, 38–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, N.; Guedes, Z.C.F. Mastigação e deglutição de crianças e adolescentes obesos. Rev. CEFAC 2016, 18, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mores, R.; Delgado, S.E.; Martins, N.F.; Anderle, P.; Longaray, C.; Pasqualeto, V.M.; Berbert, M.B. Caracterização dos distúrbios de sono, ronco e alterações do sistema estomatognático de obesos candidatos à Cirurgia Bariátrica. Rev. Bras. Obes. Nutr. Emagrecimento 2017, 11, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Red Para la Lectoescritura Inicial de Centroamérica y el Caribe. Diseño y Realización de Revisiones Sistemáticas. Una Guía de Formación para Investigadores de Lectoescritura Inicial (LEI); Ediciones RedLEI: Guatemala, 2021; Available online: https://red-lei.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Directrices-de-Revisiones-Sistematicas.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Beltrán, O.A. Revisiones sistemáticas de la literature. Rev. Colomb. Gastroenterol. 2005, 20, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez de Dios, J.; Balaguer Santamaría, A. Valoración crítica de artículos científicos. Parte 2: Revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. FAPap Monogr. 2021, 6, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Landa-Ramírez, E.; Arredondo-Pantaleón, A. Herramienta Pico para la formulación y búsqueda de preguntas clínicamente relevantes en la psicooncología basada en la evidencia. Psicooncología 2014, 11, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergunta, D. Estrategia Pico para la construcción de la pregunta de investigación y la búsqueda de evidencias. Rev. Latino Enfermagem. 2007, 15. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283522391_Estrategia_pico_para_la_construccion_de_la_pregunta_de_investigacion_y_la_bsqueda_de_evidencias (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. Declaración PRISMA: Una propuesta para mejorar la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Med. Clín. 2012, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.M.; del Castillo, M.D.M. Plan de cuidados estandarizado en cirugía bariátrica. NURE Investig. Rev. Cien. Enferm. 2006, 20, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Pachón Salem, L.E. Formulación de criterios para registrar posición lingual en pacientes con deglución atípica mediante Glumap. Areté 2016, 16, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Fuenzalida, R.; Hernández-Mosqueira, C.; Serey, J.P. Alteraciones Estructurales y Funcionales del Sistema Estomatognático: Manejo fonoaudiológico. Areté 2017, 17, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzan Berlese, D.; Copetti, F.; Maciel Weimmann, A.R.; Fabtinel Fontana, P.; Bonfanti Haeffner, L.S. Atividade dos Músculos Masseter e Temporal em Relação às Características Miofuncionais das Funções de Mastigação e deglutição em obesos. Distúrbios Comun. 2012, 24, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Mosquim, V.; Foratoti Junior, G.A.; Saory Hissano, W.; Wang y, L.; de Carvalho Sales Peres, S.H. Obesidade, cirurgia bariátrica e O impactO na saúde bucal: RevisãO de literature. Rev. Salusvita 2019, 38, 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto, S.; Sudo, E.; Matsuse, T.; Ohga, E.; Ishii, T.; Ouch, Y.; Fukuchi, Y. Impaired swallowing reflex in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest 1999, 116, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godlewski, A.E.; Veyrune, J.L.; Nicolas, E.; Ciangura, C.A.; Chaussain, C.C.; Czernichow, S.; Basdevant, A.; Hennequin, M. Effect of dental status on changes in mastication in patients with obesity following bariatric surgery. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zicari, A.M.; Marzo, G.; Rugiano, A.; Celani, C.; Carbone, M.P.; Tecco, S.; Duse, M. Habitual snoring and atopic state: Correlations with respiratory function and teeth occlusion. BMC Pediatrics 2012, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, G.; Gamez, A.S.; Molinari, N.; Kacimi, D.; Vachier, I.; Paganin, F.; Chanez, P.; Bourdin, A. Distal airway impairment in obese normoreactive women. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 707856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, B.W.; Berger, K.I.; Segal, L.N.; Stabile, A.; Coles, K.D.; Parikh, M.; Goldring, R.M. Airway dysfunction in obesity: Response to voluntary restoration of end expiratory lung volume. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouwels, S.; Smeenk, F.W.; Manschot, L.; Lascaris, B.; Nienhuijs, S.; Bouwman, R.A.; Buise, M.P. Perioperative respiratory care in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery: Implications for clinical practice. Respir. Med. 2016, 117, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulek, A.; Mulic, A.; Hogset, M.; Utheim, T.P.; Sehic, A. Therapeutic strategies for dry mouth management with emphasis on electrostimulation as a treatment option. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 2021, 6043488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, B.W.; Berger, K.I.; Ali, S.; Segal, L.N.; Donnino, R.; Katz, S.; Parikh, M.; Goldring, R.M. Pulmonary vascular congestion: A mechanism for distal lung unit dysfunction in obesity. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Felício, C.M.; da Silva Dias, F.V.; Trawitzki, L.V.V. Obstructive sleep apnea: Focus on myofunctional therapy. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2018, 10, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, S.; Fei, L.; D’Amico, R.; Giardiello, C.; Allaria, A.; Cotrufo, P. Binge eating disorder and related features in bariatric surgery candidates. Open Med. 2019, 14, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzorni, N.; Radovanovic, D.; Pecis, M.; Lorusso, R.; Annoni, F.; Bartorelli, A.; Rizzi, M.; Schindler, A.; Santus, P. Dysphagia symptoms in obstructive sleep apnea: Prevalence and clinical correlates. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrente-Sánchez, M.J.; Ferer-Márquez, M.; Estébanez-Ferrero, B.; Jiménez-Lasserrotte, M.D.; Ruiz-Muelle, A.; Ventura-Miranda, M.I.; Dobarrio-Sanz, I.; Granero-Molina, J. Social support for people with morbid obesity in a bariatric surgery programme: A qualitative descriptive study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Womble, J.T.; McQuade, V.L.; Ihrie, M.D.; Ingram, J.L. Imbalanced coagulation in the airway of Type-2 high asthma with comorbid obesity. J. Asthma Allergy 2021, 14, 967–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deane, S.; Thomson, A. Obesity and the pulmonologist. Arch. Dis. Child. 2006, 91, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameswaran, K.; Todd, D.C.; Soth, M. Altered respiratory physiology in obesity. Can. Respir. J. 2006, 13, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammit, C.; Liddicoat, H.; Moonsie, I.; Makker, H. Obesity and respiratory diseases. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2012, 3, 335–343. [Google Scholar]

- Porhomayon, J.; Papadakos, P.; Singh, A.; Nader, N.D. Alteration in respiratory physiology in obesity for anesthesia-critical care physician. HSR Proc. Intens. Care Cardiovasc. Anesth. 2011, 3, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mizraji, M.; Freese, A.M.; Bianchi, R. Sistema estomatognático. Actas Odontológicas 2012, 9, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha de Souza, L.B.; Medeiros Pereira, R.; Marques Dos Santos, M.; Almeida Godoy, C.M. Fundamental frequency, phonation maximum time and vocal complaints in morbidly obese women. Arq. Bras. Cir. Dig. 2014, 27, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseini, M.; Wood, G.C.; Seiler, J.; Argyropoulos, G.; Irving, B.A.; Gerhard, G.S.; Benotti, P.; Still, C.; Rolston, D. Gastrointestinal symptoms in morbid obesity. Front. Med. 2014, 1, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braude Canterji, M.; Miranda Correa, S.P.; Vargas, G.S.; Ruttkay Pereira, J.L.; Finard, S.A. Intervenção fonoaudiológica na cirurgia bariátrica do idoso: Relato De Caso. Arq. Bras. Cir. Dig. 2015, 28, 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, L.E.; Murphy, P.B.; Hart, N. Respiratory management of the obese patient undergoing surgery. J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nath, A.; Yewale, S.; Tran, T.; Brebbia, J.S.; Shope, T.R.; Koch, T.R. Dysphagia after vertical sleeve gastrectomy: Evaluation of risk factors and assessment of endoscopic intervention. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 10371–10379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickerts, L.; Forsberg, S.; Bouvier, F.; Jakobsson, J. Monitoring respiration and oxygen saturation in patients during the first night after elective bariatric surgery: A cohort study. F1000 Res. 2017, 6, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.W.; Seeley, R.J.; Zeltser, L.M.; Drewnowski, A.; Ravussin, E.; Redman, L.M.; Leibel, R.L. Obesity pathogenesis: An endocrine society scientific statement. Endocr. Rev. 2017, 38, 267–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões da Rocha, M.R.; Souza, S.; Moraes da Costa, C.; Bertelli Merino, D.F.; de Lima Montebelo, M.I.; Pazzianotto-Forti, R.J. Airway positive pressure vs. exercises with inspiratory loading focused on pulmonary and respiratory muscular functions in the postoperative period of bariatric surgery. Arq. Bras. Cir. Dig. 2018, 31, e1363. [Google Scholar]

- Jehan, S.; Myers, A.K.; Zizi, F.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Jean-Louis, G.; McFarlane, S.I. Obesity, obstructive sleep apnea and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Epidemiology and pathophysiologic insights. Sleep Med. Disord. Int. J. 2018, 2, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Meurgey, J.H.; Brown, R.; Woroszyl-Chrusciel, A.; Steier, J. Peri-operative treatment of sleep-disordered breathing and outcomes in bariatric patients. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S144–S152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhlesi, B.; Masa, J.F.; Brozek, J.L.; Gurubhagavatula, I.; Murphy, P.B.; Piper, A.J.; Tulaimat, A.; Afshar, M.; Balachandran, J.S.; Dweik, R.A.; et al. Evaluation and management of obesity hypoventilation syndrome. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, e6–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Anna, M.; Carvalhal, R.F.; Oliveira, F.; Zin, W.A.; Lopes, A.J.; Lugon, R.J.; Guimarães, F.S. Mecânica respiratória de pacientes com obesidade morbid. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2019, 45, e20180311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaruvongvanich, V.; Matar, R.; Ravi, K.; Murad, M.H.; Vantanasiri, K.; Wongjarupong, N.; Ungprasert, P.; Vargas, E.J.; Maselli, D.B.; Prokop, L.J.; et al. Esophageal pathophysiologic changes and adenocarcinoma after bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2020, 11, e00225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas Giglio, L.; Felício, C.M.D.; Voi Trawitzki, L. Orofacial functions and forces in male and female healthy young and adults. Codas 2020, 32, e20190045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, R.; Barlattani, A., Jr.; Perrone, M.A.; Basili, M.; Miranda, M.; Costacurta, M.; Gualtieri, P.; Pujia, A.; Merra, G.; Bollero, P. Obesity, bariatric surgery and periodontal disease: A literature update. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 5036–5045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- García-Delgado, Y.; López-Madrazo-Hernández, M.J.; Alvarado-Martel, D.; Miranda-Calderín, G.; Ugarte-Lopetegui, A.; González-Medina, R.A.; Wägner, A.M. Prehabilitation for Bariatric Surgery: A Randomized, Controlled Trial Protocol and Pilot Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlese, D.B.; Fontana, P.F.F.; Botton, L.; Weimnann, A.R.M.; Haeffner, L.S. Características miofuncionais de obesos respiradores orais e nasais. Rev. Codas 2012, 17, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques Gonçalves, R.D.F.; Zimberg Chehter, E. Masticatory profile of morbidly obese patients undergoing gastroplasty/Perfil mastigatorio de obesos morbidos submetidos a gastroplastia. Rev. CEFAC 2012, 14, 489–498. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.S.; Tanigute, C.C.; Tessitore, A. A necessidade da avaliação fonoaudiológica no protocolo de pacientes candidatos à cirurgia bariátrica. Rev. CEFAC 2014, 16, 1655–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pd Azevedo, A.; Cd Santos, C.; Cd Fonseca, D. Transtorno da compulsão alimentar periódica. Arch. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 31, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Zimberg, E. Speech therapy intervention in morbidly obese undergoing fobi-capell gastroplasty method. ABCD. Arq. Bras. Cir. Dig. 2016, 29, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Álvarez Hernández, J. Disfagia Orofaríngea: Soluciones Multidisciplinares; Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier Torres, G.M.; Hernandez Alvez, C. Physiology of exercise in orofacial motricity: Knowledge about the issue. Rev. CEFAC 2019, 21, e14318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte Aznar, F.; Aznar, F.D.; Lauris, J.R.; Adami Chaim, E.; Cazzo, E.; Sales-Peres, S.H. Dental wear and tooth loss in morbid obese patients after bariatric surgery. Arq. Bras. Cir. Dig. 2019, 32, e1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva Gebara, T.; Mocelin Polli, G.; Wanderbroocke, A.C. Eating and bariatric surgery: Social representations of obese people. Psicol. Ciência Profissão 2021, 41, e222795. [Google Scholar]

- Lemme, E.M.O.; Alvariz, A.C.; Pereira, G.L. Esophageal functional disorders in the pre-operatory evaluation of bariatric surgery. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2021, 58, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas Lima, A.C.D.; Costa Albuquerque, R.; Andrade Cunha, D.A.; Dantas Lima, C.; Henrique Lima, S.J.; Justino Silva, H. Relation of sensory processing and stomatognical system of oral respiratory children. Codas 2021, 34, e20200251. [Google Scholar]

- Mafort, T.T.; Rufino, R.; Costa, C.H.; Lopes, A.J. Obesity: Systemic and pulmonary complications, biochemical abnormalities, and impairment of lung function. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2016, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguiar, I.C.; Freitas, W.R.; Santos, I.R.; Apostolico, N.; Nacif, S.R.; Urbano, J.J.; Fonsêca, N.T.; Thuler, F.R.; Ilias, E.J.; Kassab, P.; et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and pulmonary function in patients with severe obesity before and after bariatric surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2014, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, M.P.; Evangelisti, M.; Martella, S.; Barreto, M.; Del Pozzo, M. Can myofunctional therapy increase tongue tone and reduce symptoms in children with sleep-disordered breathing? Sleep Breath 2017, 21, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparroz, F.; Campanholo, M.; Stefanini, R.; Vidigal, T.; Haddad, L.; Bittencourt, L.R.; Tufik, S.; Haddad, F. Laryngopharyngeal reflux and dysphagia in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: Is there an association? Sleep Breath 2019, 23, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristo, I.; Paireder, M.; Jomrich, G.; Felsenreich, D.M.; Fischer, M.; Hennerbichler, F.P.; Langer, F.B.; Prager, G.; Schoppmann, S.F. Silent gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with morbid obesity prior to primary metabolic surgery. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 4885–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Munoz, C.P.; Haidar, Z.S. Neuro-Muscular Dentistry: The “diamond’ concept of electro-stimulation potential for stomato-gnathic and oro-dental conditions. Head Face Med. 2021, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| P: Patient or problem of interest (Population) | Obese patient and post-bariatric surgery |

| I: Intervention | Assessment of the stomatognathic system |

| C: Comparison | Stomatognathic system |

| O: Outcome | Alterations or changes in anatomical and functional structures |

| Source | Keyword | Related Terms |

|---|---|---|

| DECS | Distal airways | No records found |

| MESH | Distal airways | No records found |

| DECS | Obesity | No records found |

| MESH | Obesity | Morbid obesity, excess adipose tissue, abnormal weight gain |

| DECS | Overweight | No records found |

| MESH | Overweight | Excess weight, increased body fat, increased adipose tissue |

| DECS | Bariatric surgery | No records found |

| MESH | Bariatric surgery | Weight reduction, metabolic surgery, bariatric surgical procedure, stomach stapling, gastroenterostomy, gastric bypass, gastroplasty, jejunoileal bypass, lobectomy, lipoabdominoplasty |

| DECS | Upper respiratory tract | No records found |

| MESH | Upper respiratory tract | Respiratory system, respiratory tract, upper respiratory tract |

| DECS | Lower respiratory tract | No records found |

| MESH | Lower respiratory tract | No records found |

| DECS | Respiratory system | No records found |

| MESH | Respiratory system | Airways, respiratory function |

| DECS | Masticatory system | No records found |

| MESH | Masticatory system | Stomatognathic system |

| DECS | Masticatory apparatus | No records found |

| MESH | Masticatory apparatus | No records found |

| DECS | Masticatory dynamic | No records found |

| MESH | Masticatory dynamic | No records found |

| DECS | Swallowing disorder | No records found |

| MESH | Swallowing disorder | Swallowing disorder, difficulty swallowing, dysphagia |

| DECS | Swallowing reflex | No records found |

| MESH | Swallowing reflex | No records found |

| DECS | Swallowing physiology | No records found |

| MESH | Swallowing physiology | No records found |

| DECS | Swallowing biomechanics | No records found |

| MESH | Swallowing biomechanics | No records found |

| DECS | Dysphagia | No records found |

| MESH | Dysphagia | Swallowing disorder, neuromuscular disorder, or mechanical obstruction |

| DECS | Aspiration | No records found |

| MESH | Aspiration | Pneumonia, respiratory aspiration |

| DECS | Myofunctional disorder | No records found |

| MESH | Myofunctional disorder | No records found |

| DECS | Orofacial disorder | No records found |

| MESH | Orofacial disorder | No records found |

| DECS | Swallowing | No records found |

| MESH | Swallowing | Swallow |

| DECS | Masticatory alteration | No records found |

| MESH | Masticatory alteration | No records found |

| DECS | Orofacial motor skills | No records found |

| MESH | Orofacial motor skills | No records found |

| DECS | Myofunctional therapy | No records found |

| MESH | Myofunctional therapy | Orofacial myotherapy, orofacial myologies |

| DECS | Stomatognathic system | No records found |

| MESH | Stomatognathic system | No records found |

| DECS | Breathing | No records found |

| MESH | Breathing | Breath work |

| DECS | Suction | No records found |

| MESH | Suction | No records found |

| DECS | Speech | No records found |

| MESH | Speech | Verbal communication |

| DECS | Phonation | No records found |

| MESH | Phonation | Sound production |

| DECS | Chewing | No records found |

| MESH | Chewing | No records found |

| Database | Search Algorithm |

|---|---|

| PubMed, ProQuest, Scielo, Dialnet, EBSCO, and Springer Link | (“Bariatric Surgery”) AND (“Disorders”) AND (“Myofunctional”) |

| (“Bariatric Surgery”) AND (“Disorders”) AND (“Myofunctional” OR “Orofacial”) OR (“Disorder Physiology”) AND (“Obesity”) | |

| (“Alteration”) AND (“Masticatory System”) AND (“bariatric surgery” OR “Obese”) | |

| (“Deglutition”) AND (“bariatric surgery” OR “Obese”) | |

| (“Orofacial Motor Skills”) AND (“Physiology”) | |

| (“Myofunctional Therapy” OR “Stomatognathic System”) AND (“Physiology”) | |

| (“Orofacial”) AND (“Disorder”) AND (“bariatric surgery”) AND (“Respiration” OR “Suction” OR “Swallowing” OR “Speech” OR “Phonation”) | |

| (“Orofacial” OR “Bariatric Surgery”) AND (“Breathing”) | |

| (“Orofacial”) AND (“Disorder”) AND (“Bariatric Surgery”) AND (“Suction”) | |

| (“Disorder”) AND (“Bariatric Surgery”) AND (“Swallowing”) | |

| (“Bariatric Surgery”) AND (“Speech”) | |

| (“Disorder”) AND (“Bariatric Surgery”) AND (“Phonation”) | |

| (“Orofacial”) AND (“Disorder”) AND (“Obesity”) AND (“Breathing”) | |

| (“Orofacial”) AND (“Disorder”) AND (“Obesity”) AND (“Suction”) | |

| (“Orofacial”) AND (“Obesity”) AND (“Swallowing”) | |

| (“Orofacial”) AND (“Disorder”) AND (“Obesity”) AND (“Speech”) | |

| (“Orofacial”) AND (“Disorder”) AND (“Obesity”) AND (“Phonation”) | |

| (“Distal Airways”) AND (“Obesity”) | |

| (“Distal Airways”) AND (“Overweight”) | |

| (“Distal Airways”) AND (“Obesity”) AND (“Bariatric Surgery”) | |

| (“Distal Airways”) AND (“Overweight”) AND (“Bariatric Surgery”) | |

| (“Upper Airways”) AND (“Obesity”) | |

| (“Upper Respiratory Tract”) AND (“Overweight”) | |

| (“Upper Airway”) AND (“Overweight”) AND (“Bariatric Surgery”) | |

| (“Lower Respiratory Tract”) AND (“Obesity”) | |

| (“Lower Respiratory”) AND (“Overweight”) | |

| (“Lower Respiratory Tract”) AND (“Obesity”) AND (“Bariatric Surgery”) | |

| (“Respiratory System”) AND (“Obesity”) | |

| (“Masticatory System”) AND (“Obesity”) | |

| (“Masticatory Apparatus”) AND (“Obesity”) | |

| (“Masticatory Dynamics”) AND (“Obesity”) | |

| (“Swallowing Disorder”) AND (“Obesity”) | |

| (“Swallowing Reflex”) AND (“Obesity”) | |

| (“Swallowing Physiology”) AND (“Obesity”) | |

| (“Swallowing Biomechanics”) AND (“Obesity”) | |

| (“Dysphagia”) AND (“Obesity”) | |

| (“Aspiration”) AND (“Obesity”) |

| Database | Total Articles | Type of Document | Period | Incomplete and/or Duplicate Texts | No Access | Non-Compliance with Criteria | Selected Articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PUBMED | 460,295 | 29,752 | 330,324 | 79,016 | 20,345 | 832 | 26 |

| PROQUEST | 580,424 | 259,904 | 18,580 | 18,667 | 24,348 | 258,901 | 24 |

| SCIELO | 330 | 120 | 36 | 32 | 15 | 111 | 16 |

| DIALNET | 356 | 43 | 43 | 1 | 0 | 266 | 3 |

| EBSCO | 16,405 | 5280 | 4012 | 3 | 0 | 7105 | 5 |

| SPRINGER LINK | 11,314 | 4555 | 3868 | 530 | 2300 | 55 | 6 |

| TOTAL | 1,069,124 | 299,654 | 356,863 | 98,249 | 47,008 | 267,270 | 80 |

| Matches/Databases | PUBMED | PROQUEST | SCIELO | DIALNET | EBSCO | SPRINGER LINK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity + Bariatric Surgery | 7 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Obesity + Stomatognathic System | 6 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Obesity + Physiology | 9 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Obesity + Upper Airway | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Obesity + Lower Airway | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 26 | 24 | 16 | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| N | Database | Title | Author | Year | URL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DIALNET | Standardized care plan in bariatric surgery [27] | Mesa García, C; Muñoz Del Castillo, M. | 2016 | https://dialnet-unirioja-es.unipamplona.basesdedatosezproxy.com/servlet/articulo?codigo=7801587 (accessed on 23 November 2021) |

| 2 | DIALNET | Formulation of criteria to record tongue position in patients with atypical swallowing [28] | Pachon Salem, L. E. | 2016 | https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/6045809.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2021) |

| 3 | DIALNET | Structural and Functional Alterations of the Stomatognathic System: Speech-Language Management [29] | Pérez Serey, J; Hernández Mosqueira, C; Fuenzalida Cabezas, R. | 2021 | https://arete.ibero.edu.co/article/view/art.17105 (accessed on 23 November 2021) |

| 4 | EBSCO | Myofunctional and electromyographic characteristics of obese adolescent children [30] | Bolzan Berlese, D; Copetti, F; Maciel Weimmann, A; Fantinel Ferreira, P; Bonfanti Haeffner, L. | 2013 | https://web-s-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.uniminuto.edu/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=97de324b-fcf4-47c4-a413-4b7a6cde6c62%40redis&bdata=Jmxhbmc9ZXMmc2l0ZT1laG9zdC1saXZlJnNjb3BlPXNpdGU%3d#AN=90594980&db=a9h (accessed on 04 December 2021) |

| 5 | EBSCO | Pulmonary Function and Obesity [31] | Carpio, C., Santiago, A., García De Lorenzo, A; Álvarez-Sala, R | 2014 | https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0212-16112014001200009 (accessed on 04 December 2021) |

| 6 | EBSCO | Characterization of sleep disorders, snoring, and alterations of the stomatognathic system of obese candidates for bariatric surgery [20] | Mores, R; Delgado, S. E; Martins, N. F; Anderle, P; Da Silva Longaray, C; Pasqualeto, V. M; Batista Berbert, M. C. | 2017 | http://www.rbone.com.br/index.php/rbone/article/view/447 (accessed on 04 December 2021) |

| 7 | EBSCO | Maximum phonation time in people with obesity not undergoing or undergoing bariatric surgery [11] | Fonseca, A; Salgado, W; Dantas, R. | 2019 | https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jobe/2019/5903621/ (accessed on 04 December 2021) |

| 8 | EBSCO | Obesity, bariatric surgery, and the impact on oral health: A review of the literature [32] | Mosquim, V; Aparecido Foratori, J. G; Saory Hissano, W; Wang, L; Sales Peres, S. | 2019 | https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/biblio-1051047 (accessed on 04 December 2021) |

| 9 | PROQUEST | Impaired swallowing reflex in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome [33] | Teramoto, S; Sudo, E; Matsuse, T; Ohga, E. | 1999 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/200498630/9EDD348CC9A4A96PQ/2?accountid=48797&forcedol=true (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 10 | PROQUEST | The stomatognathic system and body scheme [1] | Barreto, J. F | 1999 | https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/283/28330405.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 11 | PROQUEST | Obesity and the lungs: 2 · Obesity and sleep-disordered breathing [34] | Crummy, F; Piper, A. J; Naughton, M. T | 2008 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/1781775154/FFC00B28C8B14725PQ/73?accountid=48797&forcedol=true&forcedol=true (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 12 | PROQUEST | The effect of dental status on changes in chewing in obese patients after bariatric surgery [35] | Godlewski, A. E; Veyrune, J; Ciangura, C; Chaussain, C. | 2011 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/1306252768/9EDD348CC9A4A96PQ/4?accountid=48797&forcedol=true (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 13 | PROQUEST | Habitual snoring and atopic status: Correlations with respiratory function and tooth occlusion [36] | Zicari, A. M; Marzo, G; Rugiano, A; Celani, C; Carbone, M. P. | 2012 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/1197719038/8A83C372D8DF4F3DPQ/9 (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 14 | PROQUEST | Impairment of the distal airway in normally reactive obese women [37] | Marin, G; Gamez, A. S; Molinari, N; Kacimi, D; Vachier, I. | 2013 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/1434621519/2E1BA5ED485B4119PQ/4?accountid=48797 (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 15 | PROQUEST | Airway dysfunction in obesity: The response to voluntary restoration of end-expiratory lung volume [38] | Oppenheimer, Beno W; Berger, Kenneth I; Segal, Leopoldo N; Stabile, A; Coles, K. | 2014 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/1494399689/2E1BA5ED485B4119PQ/2?accountid=48797 (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 16 | PROQUEST | Perioperative respiratory care in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery: Implications for clinical practice [39] | Pouwels, S; Smeenk, F. W; Manschot, L; Lascaris, B; Nienhuijs, S; Bouwman, R. A; Buise, M. P. | 2016 | https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0954611116301287 (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 17 | PROQUEST | Therapeutic strategies for the management of dry mouth with emphasis on electrostimulation as a treatment option [40] | Tulek, A; Mulic, A; Hogset, M; Utheim, T. P; Sehic, A. | 2021 | https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijd/2021/6043488/ (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 18 | PROQUEST | Pulmonary vascular congestion: A mechanism for distal pulmonary unit dysfunction in obesity [41] | Oppenheimer, Beno W; Berger, Kenneth I; Saleem, Alí; Segal, Leopoldo N; Donnino, R. | 2016 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/1777735040/2E1BA5ED485B4119PQ/1?accountid=48797&forcedol=true (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 19 | PROQUEST | Comparison of Interview to Questionnaire for Assessment of Eating Disorders after Bariatric Surgery [4] | Globus, I; Kissileff, H. R; Hamm, J. D; Herzog, M; Mitchell, J. E; Latzer, Y. | 2021 | https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/10/6/1174 (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 20 | PROQUEST | Food insecurity as a determinant of obesity in humans: The insurance hypothesis [3] | Ortiga, D; Andrews, C; Bateson, M. | 2017 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/1988264531/144D2D2995EF403FPQ/471 (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 21 | PROQUEST | The impact of bariatric surgery on sleep-disordered breathing parameters from overnight polysomnography and home sleep apnea testing [13] | Mashaqi, S; Steffen, K; Crosby, R; Garcia, L; Cureus, P. | 2018 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/2080487482/8E81C0CD3DA94C5EPQ/198 (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 22 | PROQUEST | Perceived oral health in patients after bariatric surgery using measures of quality of life related to oral health [2] | Karlsson, L; Carlsson, J; Jenneborg, K; Kjaeldgaard, M. | 2018 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/2266411926/8E81C0CD3DA94C5EPQ/155 (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 23 | PROQUEST | Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Focus on Myofunctional Therapy [42] | Felicio, C. M; Da Silva Dias, F; Voi Trawitzki, L. | 2018 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/2229610711/ECF01209F16B4AFCPQ/12 (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 24 | PROQUEST | Why is primary obesity a disease? [7] | De Lorenzo, A; Gratteri, S; Gualtieri, P; Cammarano, A; Bertucci, P. | 2019 | https://www.proquest.com/resultsol/144D2D2995EF403FPQ/28#scrollTo (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 25 | PROQUEST | Binge eating disorder and related features in candidates for bariatric surgery [43] | Cella, S., Fei, L; D’Amico, R; Giardiello, C; Allaria, A; Cotrufo, P. | 2019 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/2244691685/8E81C0CD3DA94C5EPQ/67 (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 26 | PROQUEST | Obesity, a risk factor in COVID-19 [5] | Cadea, E. | 2021 | https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Paginas/Obesidad-un-factor-de-riesgo-en-el-covid-19.aspx (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 27 | PROQUEST | Dysphagia symptoms in obstructive sleep apnea: Prevalence and clinical correlates [44] | Pizzorni, N; Radovanovic, D; Pecis, M; Lorusso, R; Annoni, F; Bartorelli, A; Santus, P. | 2021 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/2528901432/CDDFC8E76B784FF0PQ/20 (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 28 | PROQUEST | Obesity in the world [8] | Malo-Serrano, M; Castillo, N; Pajita, D. | 2017 | http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?pid=S1025-55832017000200011&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 29 | PROQUEST | Social support for people with morbid obesity in a bariatric surgery program: A qualitative descriptive study [45] | Torrente-Sánchez et al. | 2021 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/2544977715/8E81C0CD3DA94C5EPQ/ (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 30 | PROQUEST | The development of eating and eating disorders after bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis [14] | Victor Taba, J; Oliveira Suzuki, M; Sayuri do Nascimento, F; Ryuchi Iuamoto, L; Hsing, W. T; Zumerkorn Pipek, L; Andraus, W. | 2021 | https://www.proquest.com/docview/2554777851/8E81C0CD3DA94C5EPQ/28 (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 31 | PROQUEST | Design and Conduct of Systematic Reviews: A training guide for Early Literacy (EL) researchers [21] | Red Para La Lectoescritura Inicial De Centroamérica Y El Caribe–Redlei- | 2021 | https://red-lei.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Directrices-de-Revisiones-Sistematicas.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 32 | PROQUEST | Imbalanced coagulation in the airways of Type 2-high asthma with comorbid obesity [46] | Womble, J. T; McQuade, V. L; Ihrie, M. D; Ingram, J. L. | 2021 | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8364356/ (accessed on 17 December 2021) |

| 33 | PUBMED | Obesity and the pulmonologist [47] | Deane, S; Thomson, A. | 2006 | https://adc.bmj.com/content/91/2/188.short (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 34 | PUBMED | Altered respiratory physiology in obesity [48] | Parameswaran, K; Todd, D. C; Soth, M. | 2006 | https://www.hindawi.com/journals/crj/2006/834786/ (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 35 | PUBMED | Obesity and respiratory diseases [49] | Zammit, C; Liddicoat, H; Moonsie, I; Makker, H. | 2006 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21116339/ (accessed on13 January 2022) |

| 36 | PUBMED | Altered respiratory physiology in obesity for the anesthesiologist-critical physician [50] | Porhomayon, J; Papadakos, P; Singh, A; Nader, N. D. | 2011 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23439281/ (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 37 | PUBMED | The stomatognathic system [51] | Mizraji, M; Freese, A. M; Bianchi, R. | 2012 | https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/lil-706324 (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 38 | PUBMED | Fundamental frequency, maximum phonation time, and vocal complaints in morbidly obese women [52] | Rocha de Souza, L. B; Medeiros Pereira, R; Marques dos Santos, M; Almeida Godoy, C. M. | 2014 | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4675479/ (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 39 | PUBMED | PICO tool for the formulation and search of clinically relevant questions in evidence-based psycho-oncology [24]. | Landa-Ramírez, E; Arredondo, A. | 2014 | https://www.seom.org/seomcms/images/stories/recursos/05%20PSICOVOL11N2-3w.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 40 | PUBMED | Gastrointestinal symptoms in morbid obesity–the presence of dysphagia [53] | Huseini, M; Wood, G. C; Seiler, J; Argyropoulos, G; Irving, B. A; Gerhard, G. S; Rolston, D. D. | 2014 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25593922/ (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 41 | PUBMED | Speech, hearing, and language science therapy in bariatric surgery for the elderly: A case report [54] | Braude Canterji, M; Miranda Correa, S. P; Vargas, G. S; Ruttkay Pereira, J. L; Finard, S. A. | 2015 | https://www.scielo.br/j/abcd/a/zXYmf9QDgCCspDc5wyYdwHn/?lang=pt (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 42 | PUBMED | Respiratory management of obese patients undergoing surgery [55] | Hodgson, L. E; Murphy, P. B; Hart, N. | 2015 | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4454851/ (accessed on 14 January 2022) |

| 43 | PUBMED | Dysphagia after vertical sleeve gastrectomy: An evaluation of risk factors and evaluation of endoscopic intervention [56] | Nath, A; Yewale, S; Tran, T; Brebbia, J. S; Shope, T. R; Koch, T. R. | 2016 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28058017/ (accessed on 14 January 2022) |

| 44 | PUBMED | Monitoring of respiration and oxygen saturation in patients during the first night after elective bariatric surgery: A cohort study [57] | Wickerts, L; Forsberg, S; Bouvier, F; Jakobsson, J. | 2017 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28794858/ (accessed on 14 January 2022) |

| 45 | PUBMED | The pathogenesis of obesity: A scientific statement from an endocrine society [58] | Schwartz, M. W; Seeley, R. J; Zeltser, L. M; Drewnowski, A; Ravussin, E; Redman, L. M; Leibel, R. L. | 2017 | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5546881/ (accessed on 14 January 2022) |

| 46 | PUBMED | Positive airway pressure vs. inspiratory load exercises focused on pulmonary and respiratory muscle functions in the postoperative period of bariatric surgery [59] | Simões da Rocha, M. R; Souza, S; Moraes da Costa, C; Bertelli Merino, D. F; de Lima Montebelo, M. I; Rasera-Júnior; Pazzianotto-Forti, E. M. | 2018 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29972391/ (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 47 | PUBMED | Obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Epidemiologic and pathophysiologic data [60] | Jehan, S; Myers, A. K; Zizi, F; Pandi-Perumal, S. R; Jean-Louis, G; McFarlane, S. I. | 2018 | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6112821/ (accessed on 15 January 2022) |

| 48 | PUBMED | Perioperative treatment of sleep-disordered breathing and outcomes in bariatric patients [61] | Meurgey, J. H; Brown, R; Woroszyl-Chrusciel, A; Steier, J. | 2018 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29445538/ (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 49 | PUBMED | Evaluation and management of obesity hypoventilation syndrome: An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society [62] | Mokhlesi, B; Masa, J. F; Brozek, J. L; Gurubhagavatula, I; Murphy, P. B; Piper, A. J; Teodorescu, M. | 2018 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31368798/ (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 50 | PUBMED | Breathing matters [17] | Del Negro, C. A; Funk, G. D; Feldman, J. L. | 2018 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29740175/#affiliation-3 (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 51 | PUBMED | Duration and stability of metabolically healthy obesity over 30 years [6] | Camhi, S. M; Must, A; Gona, P. N; Hankinson, A; Odegaard, A; Reis, J; Carnethon, M. R. | 2019 | https://www.nature.com/articles/s41366-018-0197-8 (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 52 | PUBMED | Respiratory mechanics of patients with morbid obesity [63] | Sant’Anna, M. D; Ferreira Carvalhal, R; Bastos de Oliveira, F. D; Araújo Zin, W; Lopes, A. J; Lugon, J. R; Silva Guimarães, F. | 2019 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31644708/ (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 53 | PUBMED | Esophageal pathophysiologic changes and adenocarcinoma after bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis [64] | Jaruvongvanich, V; Matar, R; Ravi, K; Murad, M. H; Vantanasiri, K; Wongjarupong, N; Dayyeh, B. K. A. | 2020 | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7447443/ (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 54 | PUBMED | Perception of dyspnea during inspiratory resistive load testing in obese subjects awaiting bariatric surgery [12] | Tomasini, K; Ziegler, B; Sanches, P. R. S; da Silva Junior, D. P; Thomé, P. R; Dalcin, P. D. T. R. | 2020 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32415112/ (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 55 | PUBMED | Orofacial functions and forces in healthy young and adult males and females [65] | Dantas Giglio, L; Felício, C. M. D; Voi Trawitzki, L. V. | 2020 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33174985/ (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 56 | PUBMED | Obesity, bariatric surgery, and periodontal disease: An update of the literature [66] | Franco, R; Barlattani Jr, A; Perrone, M. A; Basili, M; Miranda, M; Costacurta, M; Bollero, P. | 2020 | https://www.europeanreview.org/article/21196 (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 57 | PUBMED | Altered airway mechanics in the context of obesity and asthma [9] | Bates, J. H; Peters, U; Daphtary, N; MacLean, E. S; Hodgdon, K; Kaminsky, D. A; Dixon, A. E. | 2021 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33119471/ (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 58 | PUBMED | Pre-habilitation for bariatric surgery: A pilot study and randomized controlled trial protocol [67] | García-Delgado, Y; López-Madrazo-Hernández, M. J; Alvarado-Martel, D; Miranda-Calderín, G; Ugarte-Lopetegui, A; González-Medina, R. A; Wägner, A. M. | 2021 | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34578781/ (accessed on 13 January 2022) |

| 59 | SCIELO | Bariatric surgery [16] | Maluenda, G. F. | 2012 | https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0716864012702961 (accessed on 30 January 2022) |

| 60 | SCIELO | Myofunctional characteristics of obese mouth-nose breathers [68] | Bolzan Berlese, D; Ferreira Fontana, P. F; Botton, L; Maciel Weimnann, A. R; Bonfanti Haeffner, L. S. | 2012 | https://www.scielo.br/j/rsbf/a/NtJSY7LfJzPWyzRTsyN4cYL/?lang=pt (accessed on 30 January 2022) |

| 61 | SCIELO | Masticatory profile of morbidly obese subjects undergoing gastroplasty [69] | Marques Gonçalves, R. D. F; Zimberg Chehter, E. | 2012 | https://www.scielo.br/j/rcefac/a/cDMcdK4TtTt5WhQzpLR6pzD/?lang=pt (accessed on 30 January 2022) |

| 62 | SCIELO | The need for speech therapy assessment in the protocol of patients who are candidates for bariatric surgery [70] | Guerra Silva, A. S; Camargo Tanigute, C; Tessitore, A. | 2014 | https://www.scielo.br/j/rcefac/a/bHk9QNgbvFyXmw65QDJbzcD/?lang=pt (accessed on 30 January 2022) |

| 63 | SCIELO | Binge eating disorder [71] | Pinto de Azevedo, A. P; dos Santos, C. C; Cardoso da Fonseca, D. | 2004 | https://www.scielo.br/j/rpc/a/Mbjb77bcDLvBc4HPNgkT7Yn/?lang=pt (accessed on 30 January 2022) |

| 64 | SCIELO | Obesity, a risk factor in the COVID-19 pandemic [10] | de León Ramírez, L. L; de León Ramírez, L; Ramírez, J. A. B. | 2021 | http://www.revholcien.sld.cu/index.php/holcien/article/view/43 (accessed on 30 January 2022) |

| 65 | SCIELO | Chewing and swallowing in obese children and adolescents [19] | Souza, N. C. D; Ferreira Guedes, Z. C. | 2016 | https://www.scielo.br/j/rcefac/a/HypwyzNNyb9txHVPv5RX9 mJ/?lang=pt (accessed on 30 January 2022) |

| 66 | SCIELO | Speech therapy intervention in morbidly obese patients undergoing the Fobi-Capella gastroplasty method [72] | Marques Gonçalves, R. D; Zimberg, E. | 2016 | https://www.scielo.br/j/abcd/a/crM36KrQZBYR3W5d4RtrTfm/?lang=en (accessed on 30 January 2022) |

| 67 | SCIELO | Oropharyngeal dysphagia: Multidisciplinary solutions [73] | Álvarez Hernández, J. | 2018 | https://senpe.com/libros/01_DISFAGIA_INTERACTIVO.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2022) |

| 68 | SCIELO | Physiology of exercise in orofacial motricity: Knowledge of the subject [74] | Xavier Torres, G. M; Hernández Alvez, C. | 2019 | https://www.scielo.br/j/rcefac/a/dpdn39WnSLkbj5D3hhvhhqP/?lang=en (accessed on 30 January 2022) |

| 69 | SCIELO | Chewing and swallowing in obese individuals referred for bariatric surgery/gastroplasty: A pilot study [18] | Andrade Rocha, A. C; Oliveira De Souza, N; Davison Mangilli Toni, C. | 2019 | https://www.scielo.br/j/rcefac/a/5K4ZGD3QJr8PdhyLg6fpVQB/?lang=en (accessed on 30 January 2022) |

| 70 | SCIELO | Tooth wear and tooth loss in morbidly obese patients after bariatric surgery [75] | Duarte Aznar, F; Aznar, F. D; Lauris, J. R; Adami Chaim, E; Cazzo, E; Sales Peres, S. H. D. C. | 2019 | https://www.scielo.br/j/abcd/a/xdF3p8Fjb3vWrF9r9 mbDvVw/?lang=en (accessed on 30 January 2022) |

| 71 | SCIELO | Contributions of emotional overload, emotion dysregulation, and impulsivity to eating patterns in obese patients with binge eating disorder who seek bariatric surgery [15] | Benzerouk, F; Djerada, Z; Bertin, E; Barrière, S; Gierski, F; Kaladjian, A. | 2020 | https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/12/10/3099 (accessed on 30 January 2022) |

| 72 | SCIELO | Alimentary and bariatric surgery: Social representations of obese individuals [76] | Silva Gebara, T; Mocelin Polli, G; Wanderbroocke, A. C. | 2021 | https://www.scielo.br/j/pcp/a/6XkTBNs9MYqSPkkGnh3VJ5G/abstract/?format=html&lang=en (accessed on 02 February 2022) |

| 73 | SCIELO | Functional esophageal disorders in the preoperative evaluation of bariatric surgery [77] | Oliveira Lemme, E; Cerqueira Alvariz, A; Cotta Pereira, G. | 2021 | https://www.scielo.br/j/ag/a/Wh3kSvt3xqCQY7WRnZHFDjg/abstract/?lang=pt (accessed on 02 February 2022) |

| 74 | SCIELO | The relationship of sensory processing and the stomatognathic system in children who breathe through the mouth [78] | Dantas Lima, A. C. D; Costa Albuquerque, R; Andrade Cunha, D. A; Dantas Lima, C; Henrique Lima, S. J; Justino Silva, H. | 2022 | https://www.scielo.br/j/codas/a/yRRKqnrSx59xCdXFyT6hjCg/?lang=pt (accessed on 02 February 2022) |

| 75 | SPRINGER LINK | Obesity: Systemic and pulmonary complications, biochemical abnormalities, and impaired lung function [79] | Mafort, T. T; Rufino, R; Costa, C. H; Lopes, A. J. | 2016 | https://mrmjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40248-016-0066-z (accessed on 02 February 2022) |

| 76 | SPRINGER LINK | Obstructive sleep apnea and lung function in severely obese patients prior to and after bariatric surgery: A randomized clinical trial [80] | Aguiar, I. C; Freitas, W. R; Santos, I. R; Apostolico, N; Nacif, S. R; Urbano, J. J; Oliveira, L. V. | 2014 | https://mrmjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2049-6958-9-43 (accessed on 02 February 2022) |

| 77 | SPRINGER LINK | Can myofunctional therapy increase tongue tone and reduce symptoms in children with sleep-disordered breathing? [81] | Villa, M. P; Evangelisti, M; Martella, S; Barreto, M; Del Pozzo, M. | 2017 | https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11325-017-1489-2 (accessed on 02 February 2022) |

| 78 | SPRINGER LINK | Laryngopharyngeal reflux and dysphagia in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: Is there an association? [82] | Caparroz, F; Campanholo, M; Stefanini, R; Vidigal, T; Haddad, L; Bittencourt, L. R; Haddad, F. | 2019 | https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11325-019-01844-0 (accessed on 02 February 2022) |

| 79 | SPRINGER LINK | Silent gastroesophageal reflux disease in morbidly obese patients prior to primary metabolic surgery [83] | Kristo, I; Paireder, M; Jomrich, G; Felsenreich, D. M; Fischer, M; Hennerbichler, F. P; Schoppmann, S. F. | 2020 | https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11695-020-04959-6 (accessed on 02 February 2022) |

| 80 | SPRINGER LINK | Sandoval-Munoz, C. P; Haidar, Z. S | 2021 | https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13005-021-00257-3 (accessed on 02 February 2022) |

| Obese Patient | Structure | Post-Bariatric Patient |

|---|---|---|

| Face | Theoretical information not evidenced | |

| Nose | Theoretical information not evidenced | |

| ||

| Cheeks | Theoretical information not evidenced | |

| ||

| ||

| Maxillary | Theoretical information not evidenced |

| Mandible | Theoretical information not evidenced | |

| ||

| Lips | Theoretical information not evidenced |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Oral cavity | ||

| Teeth |

| |

| Tongue | Theoretical information is not evidenced | |

| Palate | Theoretical information not evidenced | |

| ||

| ||

| Temporomandibular articulation | Theoretical information not evidenced |

| Neck | Theoretical information not evidenced |

| Muscles | Theoretical information not evidenced |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Head | Theoretical information not evidenced |

| ||

| Shoulders | Theoretical information not evidenced |

| Larynx and pharynx | Theoretical information not evidenced |

| ||

|

| Obese Patient | Function | Post-Bariatric Patient |

|---|---|---|

| Respiration | |

| Phonation | No significant improvement in MPT or maximum phonation time [11] | |

Masticatory dysfunction due to: | Mastication | Persistence of masticatory dysfunction |

Swallowing dysfunction due to:

| Swallowing |

|

Alteration of suction due to: | Suction | Theoretical information not evidenced |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gualdrón-Bobadilla, G.F.; Briceño-Martínez, A.P.; Caicedo-Téllez, V.; Pérez-Reyes, G.; Silva-Paredes, C.; Ortiz-Benavides, R.; Bernal, M.C.; Rivera-Porras, D.; Bermúdez, V. Stomatognathic System Changes in Obese Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12101541

Gualdrón-Bobadilla GF, Briceño-Martínez AP, Caicedo-Téllez V, Pérez-Reyes G, Silva-Paredes C, Ortiz-Benavides R, Bernal MC, Rivera-Porras D, Bermúdez V. Stomatognathic System Changes in Obese Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022; 12(10):1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12101541

Chicago/Turabian StyleGualdrón-Bobadilla, Gerson Fabián, Anggie Paola Briceño-Martínez, Víctor Caicedo-Téllez, Ginna Pérez-Reyes, Carlos Silva-Paredes, Rina Ortiz-Benavides, Mary Carlota Bernal, Diego Rivera-Porras, and Valmore Bermúdez. 2022. "Stomatognathic System Changes in Obese Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review" Journal of Personalized Medicine 12, no. 10: 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12101541

APA StyleGualdrón-Bobadilla, G. F., Briceño-Martínez, A. P., Caicedo-Téllez, V., Pérez-Reyes, G., Silva-Paredes, C., Ortiz-Benavides, R., Bernal, M. C., Rivera-Porras, D., & Bermúdez, V. (2022). Stomatognathic System Changes in Obese Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(10), 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12101541