Personalizing Medicine and Technologies to Address the Experiences and Needs of People with Multiple Sclerosis

Abstract

:1. Main Manuscript

1.1. The Quest for Knowledge, Expertise and Understanding

1.2. Uncertain Trajectories

1.3. Loss of Valued Roles and Activities and the Threat of a Changing Identity

1.4. Managing Fatigue and Its Impacts on Life and Relationships

1.5. Adapting to Life with MS

1.6. Personalized Medicine Addressing Uncertainty

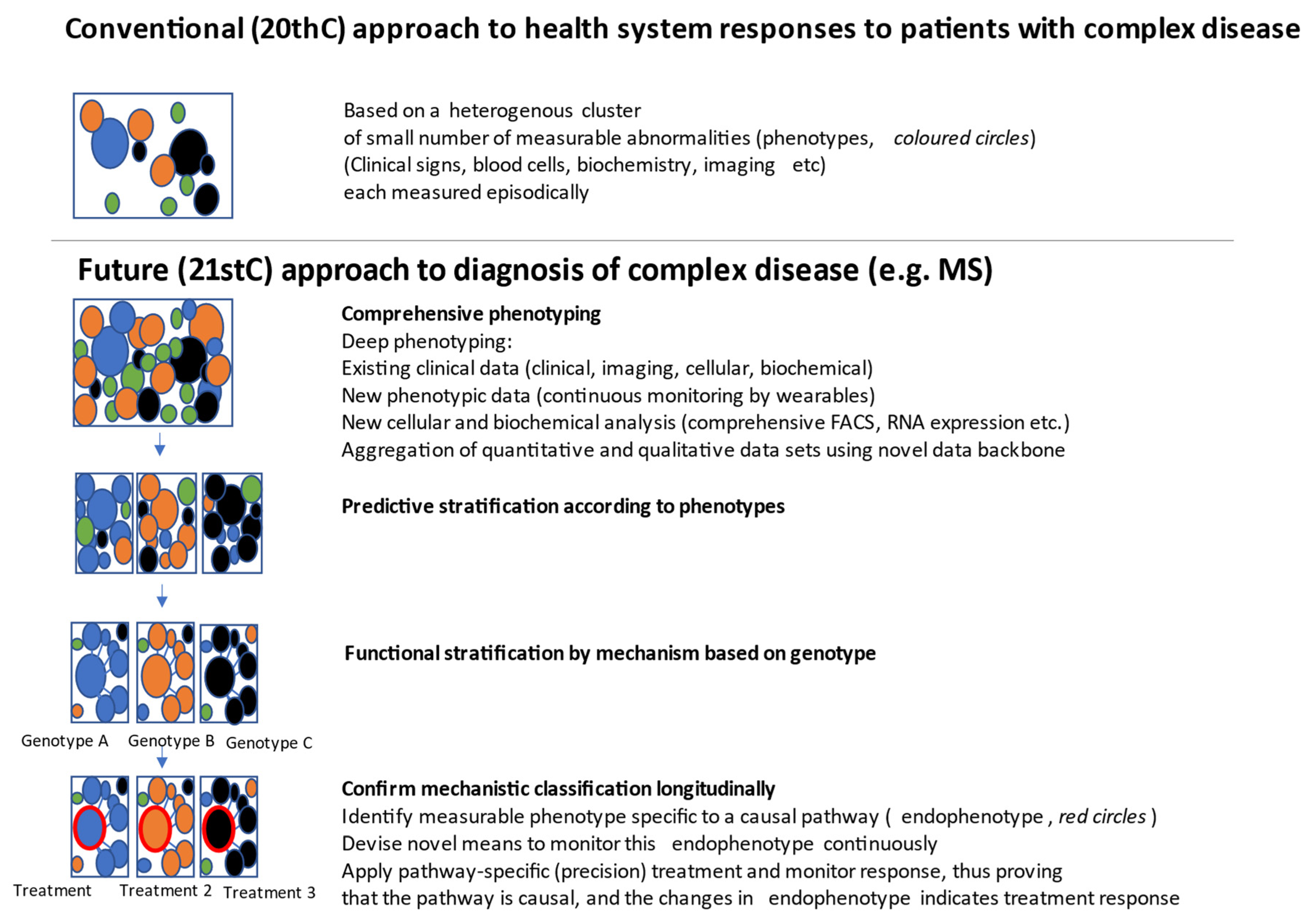

1.7. Personalized Medicine Improving Diagnosis and Monitoring

1.8. Personalized Medicine Reducing the Risk of Treatment Mistakes

1.9. Implications of Personalized Medicine for the Health Care System-Feedback, Co-Design and Implementation

2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Patient and Public Involvement

References

- Derfuss, T. Personalized medicine in multiple sclerosis: Hope or reality? BMC Med. 2012, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gafson, A.; Craner, M.J.; Matthews, P.M. Personalised medicine for multiple sclerosis care. Mult. Scler. J. 2016, 23, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Desborough, J.; Brunoro, C.; Parkinson, A.; Chisholm, K.; Elisha, M.; Drew, J.; Fanning, V.; Lueck, C.; Bruestle, A.; Cook, M.; et al. ‘It struck at the heart of who I thought I was’: A meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature examining the experiences of people with multiple sclerosis. Health Expect. 2020, 23, 1007–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campanella, P.; Lovato, E.; Marone, C.; Fallacara, L.; Mancuso, A.; Ricciardi, W.; Specchia, M.L. The impact of electronic health records on healthcare quality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dhanvijay, M.M.; Patil, S.C. Internet of Things: A survey of enabling technologies in healthcare and its applications. Comput. Netw. 2019, 153, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henschke, A. Ethics in an Age of Surveillance: Virtual Identities and Personal Information; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, A.L.; Golla, H.; Lausberg, H. What’s in a name? That which we call Multiple Sclerosis Fatigue. Mult. Scler. J. 2021, 27, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.-H.; Mathiowetz, V. Evidence-Based Literature Review on Fatigue Management and Adults with Multiple Sclerosis. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 69, 6911515067p1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehr, S.; Kaiser, T.; Kreutz, R.; Ludwig, W.-D.; Paul, F. Suggestions for improving the design of clinical trials in multiple sclerosis—Results of a systematic analysis of completed phase III trials. EPMA J. 2019, 10, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Teunissen, C.E.; Khalil, M. Neurofilaments as biomarkers in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2012, 18, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disanto, G.; Barro, C.; Benkert, P.; Naegelin, Y.; Schädelin, S.; Giardiello, A.; Zecca, C.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Leppert, D.; et al. Serum Neurofilament light: A biomarker of neuronal damage in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 81, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Housley, W.J.; Pitt, D.; Hafler, D.A. Biomarkers in multiple sclerosis. Clin. Immunol. 2015, 161, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, R.; Ramagopalan, S.; Topping, J.; Smith, P.; Solanky, B.; Schmierer, K.; Chard, D.; Giovannoni, G. A Risk Score for Predicting Multiple Sclerosis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, N.; Kehoe, M. A questionnaire study to explore the views of people with multiple sclerosis of using smartphone technology for health care purposes. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 1434–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, I.; Inojosa, H.; Dillenseger, A.; Haase, R.; Akgün, K.; Ziemssen, T. Digital Twins for Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.J. Uncertainty in the Era of Precision Medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suominen, H.; Kelly, L.; Goeuriot, L. Scholarly Influence of the Conference and Labs of the Evaluation Forum ehealth Initiative: Review and Bibliometric Study of the 2012 to 2017 Outcomes. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 7, e10961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grando, M.A.; Rozenblum, R.; Bates, D.W. (Eds.) Information Technology for Patient Empowerment in Healthcare; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pavelić, K.; Martinovic, T.; Pavelić, S.K. Do we understand the personalized medicine paradigm? EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Wherton, J.; Papoutsi, C.; Lynch, J.; Hughes, G.; A’Court, C.; Hinder, S.; Fahy, N.; Procter, R.; Shaw, S. Beyond Adoption: A New Framework for Theorizing and Evaluating Nonadoption, Abandonment, and Challenges to the Scale-Up, Spread, and Sustainability of Health and Care Technologies. J. Med Internet Res. 2017, 19, e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- D’Amico, E.; Patti, F.; Zanghì, A.; Zappia, M. A Personalized Approach in Progressive Multiple Sclerosis: The Current Status of Disease Modifying Therapies (DMTs) and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Themes [3] | Concerns Raised by PwMS [3] | Key Elements for Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Quest for knowledge, expertise and understanding | The ability of PwMS to make decisions is hampered by a lack of knowledge about the efficacy and suitability of disease modifying treatments. | Electronic health technologies that monitor and capture individual disease behaviour may compensate for limitations of access to relevant services. PwMS need to see a clear connection between information being gathered and improved treatments and outcomes resulting from personalized medicine. More information is not necessarily better; it can be overwhelming and act as an obstacle to engagement. Practice and technological design need to be able to respond when people’s desire for more or less information changes to protect against information overload. |

| 2. Uncertain trajectories | Unpredictability of symptoms on a day-to-day basis inhibits planning. Uncertainty of disease trajectory impacts life decisions. Many PwMS experience profound anxiety about long-term future progression and potential reduced independence. | Better prediction of risks of adverse events through pharmacogenomics that can identify differences in drug absorption and metabolism, guiding drug choice and dosage. Identification of disease biomarkers for improved monitoring of disease progression and treatment response, combined with development of non-invasive devices to detect these biomarkers, could address the uncertainty PwMS face throughout the illness trajectory. Feedback from patients using available technology is an essential aspect of ensuring the personalization of diagnoses and treatments. |

| 3. Loss of valued roles and activities and the threat of a changing identity | Receiving an MS diagnosis changes how a person understands themselves and their identity PwMS will have different responses to uncertainty. PwMS will understand the same information differently PwMS will have different needs for information. | Personalized medicine must be responsive to people’s different and changing through the course of their diagnosis and ongoing treatment. |

| 4. Managing fatigue and its impacts on life and relationships | PwMS report fatigue impacts their lives greatly. Fatigue is poorly understood with no current effective medications. Non-pharmacological interventions are under investigated and lack robust evidence. | Given the significant variability of living with MS, any effective personalized medicine needs not only to understand and flag fatigue, but also to respond to individuals’ varying fatigue states. |

| 5. Adapting to life with MS | PwMS develop and draw on various strategies to adapt to living with MS. Many PwMS learn to redefine their identity through re-orienting their professional and social way of life around their changed reality. | Only a personalized approach will enable a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions that may result in an amelioration of symptoms, a halt in the progression of the disease, or even a reversal of damage to the central nervous system. Sufficiently frequent monitoring of MS biomarkers via non-invasive devices has great potential to both address uncertainty faced by people with MS, as well as to direct and monitor precision medicine treatment efficacy. |

| Key Areas for Consideration | Potential Solution |

|---|---|

| Personalization needs to be a dynamic relationship between the patient and their direct health care providers as well as the larger clinical system supporting them. | Use available technology to empower patients to provide feedback to their clinicians about their progress, e.g., incidence/intensity of fatigue, monitoring of effectiveness, and side effects of treatments. Feedback is an essential aspect of ensuring the personalization of diagnoses and treatments for a heterogeneous condition such as MS. |

| People who have MS and health care providers are the proposed adopters of personalized medicine. It is likely that personalized medicine will challenge existing medical practices and have implications for clinician knowledge and the patient experience, especially in navigating an already complex health system. | Clinicians will need to make decisions spanning increasingly complex biological, environmental and lifestyle information, as well as translate this information into meaningful information for patients considering their treatment options. |

| Readying health care organizations for change extends beyond clinicians, to include policy and service leadership and capacity. | To ensure that personalized medicine is a good value proposition for all, in addition to patients, clinicians and health services need to be involved in the design, conduct, and evaluation of personalized medicine research and implementation. |

| Personalization of MS treatments future efforts in the development of technologies that can quantify the impact on disease manifestation and progress. | To optimize uptake and sustainability in clinical practice, PwMS and clinicians need to be involved in the design, implementation, and evaluation of personalized technologies. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Henschke, A.; Desborough, J.; Parkinson, A.; Brunoro, C.; Fanning, V.; Lueck, C.; Brew-Sam, N.; Brüstle, A.; Drew, J.; Chisholm, K.; et al. Personalizing Medicine and Technologies to Address the Experiences and Needs of People with Multiple Sclerosis. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11080791

Henschke A, Desborough J, Parkinson A, Brunoro C, Fanning V, Lueck C, Brew-Sam N, Brüstle A, Drew J, Chisholm K, et al. Personalizing Medicine and Technologies to Address the Experiences and Needs of People with Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021; 11(8):791. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11080791

Chicago/Turabian StyleHenschke, Adam, Jane Desborough, Anne Parkinson, Crystal Brunoro, Vanessa Fanning, Christian Lueck, Nicola Brew-Sam, Anne Brüstle, Janet Drew, Katrina Chisholm, and et al. 2021. "Personalizing Medicine and Technologies to Address the Experiences and Needs of People with Multiple Sclerosis" Journal of Personalized Medicine 11, no. 8: 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11080791

APA StyleHenschke, A., Desborough, J., Parkinson, A., Brunoro, C., Fanning, V., Lueck, C., Brew-Sam, N., Brüstle, A., Drew, J., Chisholm, K., Elisha, M., Suominen, H., Tricoli, A., Phillips, C., & Cook, M. (2021). Personalizing Medicine and Technologies to Address the Experiences and Needs of People with Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 11(8), 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11080791