Interventions to Promote a Healthy Sexuality among School Adolescents: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

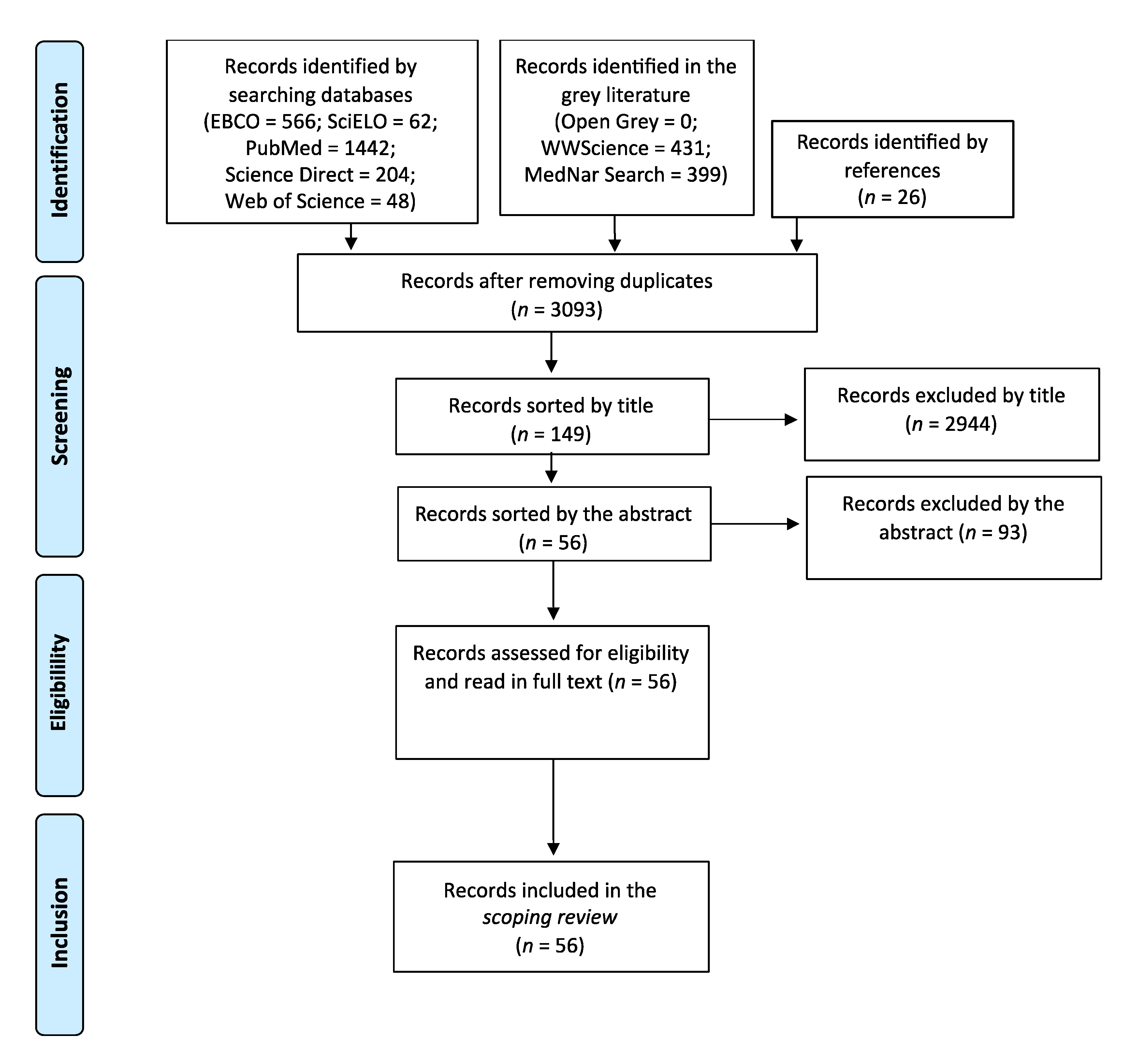

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Platform | Limiters |

|---|---|

| EBSCOhost | Adolescen * AND Sexuality AND Nurs * Portuguese, Spanish, or English language full text available |

| PubMed | Adolescen * AND Sexuality AND nurs * Portuguese, Spanish, or English language Full text available |

| SciELO | Adolescente OR adolescência AND sexualidade AND enfermagem |

| ScienceDirect | (Adolescent OR Adolescence) AND Sexuality AND (nursing OR nurse) Open access |

| Web of Science | Adolescen * AND Sexuality AND nurs * Portuguese, Spanish, or English language Full text available |

| Open Grey | Adolescen * AND Sexuality AND nurs * |

| MedNar | Adolescen * AND Sexuality AND nurs * Full text available |

| WorldWideScience | (Adolescent OR Adolescence) AND Sexuality AND (nursing OR nurse) Full text available |

| Type of Intervention | Author, Year [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82] |

|---|---|

| Event history calendar | (Martyn et al., 2012) |

| Group discussion | (Beserra et al., 2008; Fonseca et al., 2010) |

| Interventions delivered through School-Based Health Centers | (Bersamin et al., 2018; Denny et al., 2012) |

| Peer education | (Hatami et al., 2015; Okanlawon and Asuzu, 2013; Stephenson et al., 2008, 2004) |

| Online intervention | (Aragão et al., 2018; Castillo-Arcos et al., 2016; Enah et al., 2015; Souza et al., 2017; Valli and Cogo, 2013) |

| Mobile phone intervention | (Alhassan et al., 2019; Cornelius et al., 2019, 2012; French et al., 2016; Hickman and Schaar, 2018; Rokicki et al., 2017) [49] |

| Combined interventions | (Aventin et al., 2015; Barnes et al., 2004; Beserra et al., 2017; Gallegos et al., 2008; Hirvonen et al., 2021; Madeni et al., 2011; Oliveira et al., 2016) |

| Workshops | (Amaral and Fonseca, 2006; Beserra et al., 2006; Camargo and Ferrari, 2009; Carvalho et al., 2005; Freitas and Dias, 2010; Gubert et al., 2009; Levandowski and Schmidt, 2010; Santos et al., 2017; Soares et al., 2008) [50] |

| Sex education sessions | (Dunn et al., 1998; Elliott et al., 2013; Golbasi and Taskin, 2009; Grandahl et al., 2016; Lieberman et al., 2000; Moodi et al., 2013; Rani et al., 2016; Serowoky et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2006; Yakubu et al., 2019) |

| Multiple interventions program | (Henderson et al., 2007; Jemmott III et al., 1998; Jemmott et al., 2015; Lonczak et al., 2002; Richards et al., 2019; Siegel et al., 1998; Tucker et al., 2007; Villarruel et al., 2010, 2006; Wight et al., 2002) |

| Study | Abstract and Title | Introduction and Aims | Method and Data | Sampling | Data Analysis | Ethics and Bias | Results | Transferability or Generalizability | Implications and Usefulness | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [58] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 35 |

| [59] | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 35 |

| [24] | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 35 |

| [49] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 34 |

| [47] | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 34 |

| [74] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 34 |

| [43] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 34 |

| [51] | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 33 |

| [23] | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 33 |

| [27] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 33 |

| [45] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 33 |

| [70] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 33 |

| [80] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 33 |

| [33] | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 33 |

| [82] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 33 |

| [64] | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 32 |

| [65] | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 32 |

| [31] | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 32 |

| [72] | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 32 |

| [77] | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 32 |

| [54] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 31 |

| [57] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 31 |

| [46] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 31 |

| [34] | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 31 |

| [79] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 31 |

| [21] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 31 |

| [35] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 31 |

| [81] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 31 |

| [61] | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 30 |

| [68] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 30 |

| [69] | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 30 |

| [25] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 30 |

| [30] | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 30 |

| [32] | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 30 |

| [29] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 29 |

| [22] | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 29 |

| [56] | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 29 |

| [36] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 29 |

| [26] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 28 |

| [75] | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 28 |

| [53] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 27 |

| [66] | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 27 |

| [38] | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 27 |

| [20] | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 26 |

| [76] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 26 |

| [55] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 25 |

| [62] | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 25 |

| [73] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 25 |

| [28] | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 25 |

| [63] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 24 |

| [67] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 24 |

| [50] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 23 |

| [52] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 23 |

| [60] | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 23 |

| [71] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 21 |

| [78] | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 |

| Study | Country | Aim | Type of Study | Population and Sample | Interventions | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Hirvonen et al., 2021) | UK | To understand the perceptions of adolescent students regarding the use of Facebook social media in sexual and reproductive health learning. | Mixed methods | 1413 teenagers (14 to 16 years) | Combined interventions: peers’ intervention and use of private Facebook groups | Social media groups formed around peer supporters’ existing friendship networks hold potential for diffusing messages in peer-based sexual health interventions. |

| (Alhassan et al., 2019) | Ghana | To assess mobile phone usage among adolescents and young adult populations pursuing tertiary education and their use of these technologies in the education and prevention of STI. | Quantitative | 250 teenagers (18 to 24 years) | Mobile phone interventions | Future mobile phone programs should be considered for STI education and prevention, as they were found to be more comfortable than traditional messaging or phone calls. |

| (Cornelius et al., 2019) | USA | To examine adolescents in the USA and Botswana, their mobile phone and social media usage, and their perceptions of safer-sex interventions delivered via social media. | Qualitative | 28 teenagers (13 to 18 years) | Mobile phone interventions | Findings provided a starting point for researchers interested in developing a social media intervention with global implications for sexual health promotion. |

| (Golbasi and Taskin, 2009) | Turkey | To evaluate the effectiveness of school-based reproductive health education for adolescent girls on the reproductive knowledge level of the girls. | Quasi- experimental | 189 adolescents (age not mentioned) | Sex education sessions | The school-based program was conducted by nursing educators, and the program was effective in increasing the students’ levels of knowledge on reproductive health. |

| (Richards et al., 2019) | Dominican Republic | To evaluate the effectiveness of MAMI’s CSEP in changing knowledge of STIs and pregnancy. | Mixed methods | 600 students aged 11–25 years old | Multiple interventional program (comprehensive sexual education program: education sessions, interactive activities, visual aids) | The MAMI’s CSEP improved knowledge of STIs and pregnancy and attitudes toward risky sexual behavior among program recipients. |

| (Yakubu et al., 2019) | Ghana | To assess an educational intervention program on knowledge, attitude, and behavior toward pregnancy prevention based on the HBM amongst adolescent girls in Northern Ghana. | RCT | 363 adolescents (13 to 19 years). | Sex education sessions | Educational intervention, which was guided by HBM, significantly improved sexual abstinence and the knowledge of adolescents on pregnancy prevention. |

| (Aragão et al., 2018) | Brazil | To understand the perceptions of adolescent students regarding the use of Facebook social media in sexual and reproductive health learning. | Qualitative | 96 adolescents (mean age 15 years) | Online interventions (Facebook) | Virtual spaces on the Internet offer potential for the production of health care, especially among adolescents, as it contributes to the sexual and reproductive health education in an interactive, playful, and practical way. |

| (Bersamin et al., 2018) | USA | To investigate the associations between SBHCs and sexual behavior and contraceptive use among 11th graders. | Quantitative | 11840 adolescents (average age 16.6) | Interventions delivered through SBHCs | Exposure to SBHCs in general, and availability of specific reproductive health services, may be an effective strategy to support healthy sexual behaviors among youth. |

| (Hickman and Schaar, 2018) | USA | To develop and evaluate adolescent satisfaction with a text-messaging educational intervention to promote healthy behaviors, reduce the incidence of unhealthy behaviors, and prevent high-risk behaviors. | Mixed methods | 202 adolescents (14 to 18 years) | Mobile phone interventions | Text messaging is a good way to educate adolescents and promote healthy habits, as it shows a high rate of intended behavioral change by adolescents. |

| (Beserra et al., 2017) | Brazil | To analyze the perception of adolescents about the life activity “express sexuality”. | Qualitative | 25 teenagers (15 to 18 years) | Combined interventions: video projection followed by discussion and clarification of doubts | The use of videos followed by discussion is a valid and useful strategy to help adolescents in expressing their sexuality. |

| (Rokicki et al., 2017) | Ghana | To evaluate whether text-messaging programs can improve reproductive health among adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries. | RCT | 756 adolescents (14 to 24 years) | Mobile phone interventions | Text-messaging programs can lead to large improvements in reproductive health knowledge, and have the potential to lower pregnancy risk for sexually active adolescent girls. |

| (Santos et al., 2017) | Brazil | To report the experience of conducting a workshop with teenagers about STIs. | Qualitative | 34 adolescents (average age, 18 years old) | Workshops | Group educational experiences provide adolescents with the opportunity to build shared knowledge, and professionals learn about adolescents’ doubts, and therefore plan new health education meetings. |

| (Souza et al., 2017) | Brazil | To describe the online game and reflect on its theoretical– methodological basis. | Qualitative | 60 adolescents aged 15–18 years | Online game (Straight Talk) | Conceived as a pedagogic device, the online game has the capacity to implicate the adolescent in problem-based situations and allows the invention of other forms to deal with sexuality without the demand of support from a teacher. |

| (Castillo-Arcos et al., 2016) | Mexico | To evaluate the effect of an internet-based intervention to reduce sexual risk behaviors and increase resilience to sexual risk behaviors among Mexican adolescents. | Quasi- experimental | 193 adolescents (14 to 17 years) | Online interventions (sex education sessions) | The intervention improved self-reported resilience to risky sexual behaviors, though not with a reduction in those behaviors. |

| (French et al., 2016) | UK | To explore young people’s views of and experiences with a mobile phone text-messaging intervention to promote safer-sex behavior. | Qualitative | 20 adolescents (16 to 24 years) | Mobile phone interventions | The intervention increased knowledge, confidence, and safer-sex behaviors. |

| (Grandahl et al., 2016) | Sweden | To improve primary prevention of HPV by promoting vaccination and increased condom use among upper secondary schools. | RCT | 741 adolescents (aged 16 years) | Sex education sessions (face-to-face structured interventions) | Face-to-face education delivery by health care providers, such as school nurses, is a highly feasible and effective way to increase adolescents’ beliefs and behavior toward primary prevention of HPV, regardless of socioeconomic status, ethnicity, or cultural background. |

| (Oliveira et al., 2016) | Brazil | To analyze the limits and the potentialities of the Papo Reto game, for construction of knowledge in the field of sexuality with adolescents. | Qualitative | 23 adolescents (15 to 18 years) | Combined interventions (virtual game, workshops) | The game can be used as a pedagogic device for dealing with the subject of sexuality in adolescents. The results confirmed the potentiality of the contents for dealing with the complexity of reality from the point of view of gender. |

| (Rani et al., 2016) | India | To compare the knowledge and attitude regarding pubertal changes among pre-adolescent girls before and after the pubertal preparedness program | Quasi- experimental | 104 pre- adolescent (12–14 years) | Sex education sessions | Pubertal preparedness programs and FAQs reinforcement sessions are effective in enhancing knowledge and developing a favorable attitude among pre-adolescent girls. |

| (Aventin et al., 2015) | Ireland | To design, develop, and optimize an educational intervention about young men and unintended teenage pregnancy based around an interactive film. | Mixed methods | 360 adolescents (14 to 17 years) | Combined interventions: interactive film-based interventions (If I were Jack) with group discussion | The model of intervention reported in this paper was presented not as an ideal, but as an exemplar that other researchers might utilize, modify, and improve. |

| (Enah et al., 2015) | USA | To assess the acceptability and relevance of a web-based HIV prevention game for African American rural adolescents. | Mixed methods | 42 adolescents (12 to 16 years) | Online interventions (game: Fast Car) | Using games for HIV prevention was found to be appealing and acceptable, but it was not found to be the best approach to HIV prevention with the target population. |

| (Hatami et al., 2015) | Iran | To evaluate the effect of organizing interactions using peer education in schools on the knowledge and attitude toward sexual health. | Quantitative | 282 teenagers (14 to 18 years) | Peer education | The use of peer education in schools informally could enhance the knowledge and approach toward aspects of physical health, sexual behaviors, and social and mental changes among female adolescents. |

| (Jemmott et al., 2015) | 2015 South Africa | To test the effect of an HIV/STI risk-reduction intervention. | RCT | 1057 adolescents 9–18 years old | Sex education sessions | The HIV/STI risk-reduction intervention reduced unprotected intercourse and caused positive changes on theoretical constructs. Theory-based behavioral interventions with early adolescents can have long-lived effects in the context of a generalized severe HIV epidemic. |

| (Serowoky et al., 2015) | USA | To plan, implement, and evaluate a sustainable model of sexual health group programming (Cuídate) in a high school with a large Latino student population. | Quasi- experimental | 24 adolescents (13 to 18 years) | Multiple interventional program (Cuídate) | The intervention showed significant increases in STI or HIV knowledge, self-efficacy, and intention to use condoms. It can be sustained in a school-based health center with results of efficacy. |

| (Elliott et al., 2013) | UK | To assess the effectiveness of the Scottish government’s National Sexual Health Demonstration Project (HR2). | Quasi- experimental | 5283 pupils aged 15–16 years | Sex education sessions | Combining sex education and sexual health services has a limited impact on young people’s sexual health. |

| (Moodi et al., 2013) | Iran | To evaluate the effect of an educational program for puberty health on improving intermediate and high school female students’ knowledge in Birjand, Iran. | Quasi- experimental | 302 female students (mean age 12.9) | Sex education sessions | Performing educational programs during puberty has a crucial role in young girls’ knowledge increase. |

| (Okanlawon and Asuzu, 2013) | Nigeria | To involve adolescents in school-based health-promotion activities that would improve their perception of risk in sexual behavior. | Quasi- experimental | 519 adolescents | Peer education | Adolescents’ active participation in health-promotion activities should be encouraged, as it improves the perception of risk in sexual behavior among adolescents. |

| (Valli and Cogo, 2013) | Brazil | To analyze the structure of school blogs on sexuality and their utilization by adolescents. | Quantitative | 11 blogs about sexuality | Online interventions (blog) | The blog is a virtual interaction tool common among adolescents that allows the adolescent to establish relationships with other teens interested in the topic, decreasing feelings of doubt, isolation, and shyness. |

| (Cornelius et al., 2012) | USA | To understand adolescents’ perceptions of mobile cell phone text-messaging-enhanced and mobile cell phone-based HIV- prevention interventions. | Qualitative | 11 teenagers (13 to 18 years) | Mobile phone interventions | The messages increased participants’ HIV awareness and knowledge. |

| (Denny et al., 2012) | New Zealand | To determine the association between availability and quality of school health services and reproductive health outcomes among sexually active students. | Quantitative | 2745 adolescents (13 to 17 years) | Interventions delivered through SBHCs | Health services may be able to lower the incidence of pregnancy by providing access to comprehensive health services, including contraceptive care that is easily available and appropriate for the student population. |

| (Martyn et al., 2012) | USA | To explore the effects of an event history calendar approach on adolescent sexual risk communication and sexual activity. | Mixed methods | 30 adolescents (15 to 19 years) | Event history calendar | School nurses could use the event history calendar approach to improve adolescent communication on sexual risks and tailoring of interventions. |

| (Madeni et al., 2011) | Tanzania | To evaluate a reproductive health awareness program for the improvement of reproductive health for unmarried adolescent girls and boys in urban Tanzania. | Quasi- experimental | 305 adolescents (11 to 16 years) | Combined interventions (sex education sessions and group discussions) | The reproductive health program improved the students’ knowledge and behavior about sexuality and decision making after the program for both girls and boys. Their attitudes were not likely to change based on the educational intervention. |

| (Fonseca et al., 2010) | Brazil | To find the perception of adolescents on the sexual orientation actions in a public school and to identify the actions’ fragilities and potentials. | Qualitative | 15 adolescents (15 to 17 years) | Group discussions | Participative methodology promotes a welcoming and productive work climate and provides larger involvement and learning. |

| (Freitas and Dias, 2010) | Brazil | To understand teenagers’ perceptions about the development of their sexuality. | Qualitative | 12 teenagers (11 to 19 years) | Workshops | Teenagers’ perceptions about their sexuality emerged from the debates and shared knowledge during the workshops. |

| (Levandowski and Schmidt, 2010) | Brazil | To enable the exchange of experiences and reflection about sexuality-related actions and choices. | Qualitative | 270 adolescents (12 to 15 years) | Workshops | The intervention reduced psychosocial risk factors, providing a healthy development. |

| (Villarruel et al., 2010) | Mexico | To examine the effectiveness of a safer-sex program (Cuídate) on sexual behavior, use of condoms, and use of other contraceptives among Mexican youth 48 months after the intervention. | RCT | 708 adolescents (mean age 19.22) | Multiple interventional program (Cuídate) | Results demonstrated the efficacy of Cuídate among Mexican adolescents. Future research, policy, and practice efforts should be directed at sustaining safe-sex practices across adolescents’ developmental and relationship trajectories. |

| (Camargo and Ferrari, 2009) | Brazil | To analyze the knowledge of adolescents on sexuality, contraceptive methods, pregnancy, and STDs/AIDS before and after prevention workshops. | Qualitative | 117 adolescents (14 to 16 years) | Workshops | There is a need for systematic work, in the medium and long term, in schools regarding adolescent sexuality, as there was no increase in knowledge about STD transmission methods. |

| (Gubert et al., 2009) | Brazil | To address the use of educational technology as a strategy for health education among the teenagers in the school. | Qualitative | 30 teenagers (14 to 18 years) | Workshops | Nursing professionals should produce/ readjust new technologies that support the educational process in health education, valuing the skills and aspirations of adolescents, going beyond traditional health education activities based on specific actions and that do not recognize the real needs. |

| (Beserra et al., 2008) | Brazil | To investigate the adolescents’ sexuality from the educative action of a nurse in the prevention of STDs. | Qualitative | 10 adolescents (14 to 16 years) | Group discussions | The intervention allowed adolescents to explore and discuss many subjects that involved their sexuality, and it was also a moment to take actions on health education with the objective to prevent risks. |

| (Gallegos et al., 2008) | Mexico | To test the efficacy of a behavioral intervention designed to decrease risk of sexual behaviors for HIV/AIDS and unplanned pregnancies in Mexican adolescents. | RCT | 832 adolescents, age 14–17 | Combined interventions: sex education sessions and interactive games | The behavioral intervention represented an important effort, and was effective in promoting safe sexual behaviors among Mexican adolescents. |

| (Soares et al., 2008) | Brazil | To understand how adolescents live and exercise their sexuality. | Qualitative | 350 adolescents (15 to 19 years) | Workshops | The workshops favored the discussion of attitude changes in the adolescents through the information, reflection, and expression of ideas and feelings, representing a process to be complemented by the family, school, and local social politics. |

| (Henderson et al., 2007) | Scotland | To assess the impact of a theoretically based sex education program (SHARE) delivered by teachers compared with conventional education in terms of conceptions and terminations registered by the NHS. | RCT | 4196 female (mean age 20) | Multiple intervention program (SHARE) | Enhanced teacher-led school sex education (SHARE) improved knowledge and reduced regret, but did not reduce conceptions or terminations compared with conventional sex education. |

| (Tucker et al., 2007) | 2006 UK-Lothian | To test for improved outcomes for the new Lothian Healthy Respect’s SHARE on teenage sexual behavior outcomes in the Lothian region. | Quasi- experimental | 4381 secondary school pupils (average age 14.6 years) | Multiple intervention program (SHARE) | The findings demonstrated limited impact on sexual health behavior outcomes and raised questions about the likely and achievable sexual health gains for teenagers from school-based interventions. |

| (Amaral and Fonseca, 2006) | Brazil | To understand adolescents’ social representations on sexual initiation concerning gender. | Qualitative | 16 adolescents (11 to 16 years) | Workshops | The strategy allowed the understanding of the social representations of teenagers about sexual initiation, being of great importance for planning the work developed with teenagers, supporting debates and reflections on the experience of healthy and responsible sexuality by young people. |

| (Beserra et al., 2006) | Brazil | To describe an experience to promote health and prevent STDs among teenagers. | Qualitative | 28 adolescents (13 to 16 years) | Workshops | The strategy was effective at promoting teenagers’ adoption of preventative measures. |

| (Villarruel et al., 2006) | USA | To test the efficacy of a prevention intervention to reduce sexual risk behavior among Latino adolescents. | RCT | 553 adolescents, aged 13 to 18 years | Multiple interventional program (Cuídate) | Results provided evidence for efficacy for HIV prevention in decreasing sexual activity and increasing condom use among Latino adolescents. |

| (Walker et al., 2006) | Mexico | To assess effects on condom use and other sexual behavior of an HIV prevention program at school that promotes the use of condoms with and without emergency contraception. | RCT | First-year high school students (n = 10954) (16–17 years) | Sex education sessions | A rigorously designed, implemented, and evaluated HIV education course based in public high schools did not reduce risk behavior, so such courses need to be redesigned and evaluated. |

| (Carvalho et al., 2005) | Brazil | To determine how the intervention in sexual guidance was experienced by adolescents. | Qualitative | 13 adolescents (13 to 15 years) | Workshops | The analysis demonstrated a reconstruction /redefinition of meaning for the ideas related to sexuality, to gender, and to the wider social context. |

| (Barnes et al., 2004) | Australia | To evaluate the impact of changes in the health system and services on the roles and responsibilities of child health nurses and to identify professional development needs. | Qualitative | 10 nurses | Combined interventions: health education and health information displays. | The school-based youth health nurse program provides nurses with a new, challenging, autonomous role within the school environment, and the opportunity to expand their role to incorporate all aspects of the health-promoting schools’ framework. |

| (Stephenson et al., 2004) | UK | To examine the effectiveness of one form of peer-led sex education. | RCT | 8000 students (13 to 14 years) | Peer education | Peer-led sex education was effective in some ways, but broader strategies are needed to improve young people’s sexual health. The role of single-sex sessions should be further investigated. |

| (Lonczak et al., 2002) | USA | To examine the long-term effects of the full SSDP intervention on sexual behavior and associated outcomes assessed at age 21 years. | Non- randomized controlled trial | 349 former fifth-grade students (aged 21 years) | Multiple interventional program (SSDP) | A theory-based social development program that promotes academic success, social competence, and bonding to school during the elementary grades can prevent risky sexual practices and adverse health consequences in early adulthood. |

| (Wight et al., 2002) | Scotland | To determine whether a theoretically based sex education program for adolescents (SHARE) delivered by teachers reduced unsafe sexual intercourse compared with current practice. | RCT | 8430 pupils aged 13–15 years | Multiple intervention program (SHARE) | Compared with conventional sex education, this specially designed intervention did not reduce sexual risk-taking in adolescents. |

| (Lieberman et al., 2000) | USA | To assess the impact of an abstinence-based model for sexual education. | Quantitative | 312 students (mean age 12.9) | Multiple intervention program (IMPPACT) | A small-group abstinence-based intervention can have some impact on adolescents’ attitudes and relationships (particularly with their parents). |

| (Dunn et al., 1998) | Canada | To evaluate a school-based HIV prevention intervention in adolescents. | Quasi- experimental | 160 adolescents (14 to 15 years) | Sex education sessions | School-based interventions can improve adolescents’ short-term HIV/AIDS prevention knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, and behavioral intentions. |

| (Jemmott III et al., 1998) | USA | To evaluate the effects of abstinence and safer-sex HIV risk-reduction interventions on young inner-city African American adolescent’s HIV sexual risk behaviors when implemented by adult facilitators as compared with peer cofacilitators. | RCT | 659 adolescents (mean age 11.8) | Sex education sessions | Both abstinence and safer-sex interventions can reduce HIV sexual risk behaviors, but safer-sex interventions may have longer-lasting effects, and may be especially effective with sexually experienced adolescents. |

| (Siegel et al., 1998) | USA | To determine the short-term effect of a middle and high school–based AIDS and sexuality intervention (RAPP) on knowledge, self-efficacy, and behavior intention. | Non- randomized controlled trial | Middle and high school students (n = 3635) | Multiple interventional program (RAPP): games, role playing, take-home exercises | At short-term follow-up, the RAPP intervention had a powerful effect on knowledge for all students and a moderate effect on sexual self-efficacy and safe behavior intention, particularly for high school students. |

| (Stephenson et al., 2008) | UK | To assess the long-term effects of a peer-led sex education program. | RCT | 9000 students (13–14 years) | Peer education | Compared with conventional school sex education at age 13–14 y, this form of peer-led sex education was not associated with a change in teenage abortions, but may have led to fewer teenage births, and was popular with pupils. It merits consideration within broader teenage-pregnancy- prevention strategies. |

References

- World Health Organization. Implementing the global reprodutive health strategy. Policy Br. World Health Organ. Dept. Reprod. Health Res. 2006, 2, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Holland-Hall, C.; Quint, E.H. Sexuality and disability in adolescents. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 64, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullinax, M.; Mathur, S.; Santelli, J. Adolescent Sexual Health and Sexuality Education; Cherry, A.L., Baltag, V., Dillon, M.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettsch, S.L. Clarifying basic concepts: Conceptualizing sexuality. J. Sex Res. 1989, 26, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I. Health promotion in schools—A historical perspective. Promot. Educ. 2005, 12, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inchley, J.; Currie, D.; Budisavljevic, S.; Torsheim, T.; Jåstad, A.; Cosma, A.; Kelly, C.; Már Arnarsson, Á. Spotlight on Adolescent Health and Well-Being Survey in Europe and Canada International Report Volume 1. Key Findings; HBSC: Glasgow, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, H.; Shek, D.; Leung, E.; Shek, E. Development of contextually-relevant sexuality education: Lessons from a comprehensive review of adolescent sexuality education across cultures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Michielsen, K.; De Meyer, S.; Ivanova, O.; Anderson, R.; Decat, P.; Herbiet, C.; Kabiru, C.W.; Ketting, E.; Lees, J.; Moreau, C.; et al. Reorienting adolescent sexual and reproductive health research: Reflections from an international conference. Reprod. Health 2015, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shackleton, N.; Jamal, F.; Viner, R.M.; Dickson, K.; Patton, G.; Bonell, C. School-based interventions going beyond health education to promote adolescent health: Systematic review of reviews. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mmari, K.; Sabherwal, S. A review of risk and protective factors for adolescent sexual and reproductive health in developing countries: An Update. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willgerodt, M.A.; Brock, D.M.; Maughan, E.D. Public school nursing practice in the United States. J. Sch. Nurs. 2018, 34, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, Z.C.; Wallin, R.; Lee, S. The role of school health services in addressing the needs of students with chronic health conditions. J. Sch. Nurs. 2017, 33, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Santa Maria, D.; Guilamo-Ramos, V.; Jemmott, L.S.; Derouin, A.; Villarruel, A. Nurses on the front lines. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2017, 117, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.M.; Mcinerney, P.; Baldini Soares, C.; Khalil, H.; Parker, D. Guidance for the Conduct of JBI Scoping Reviews. In Joana Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017; pp. 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Hawker, S.; Payne, S.; Kerr, C.; Hardey, M.; Powell, J. Appraising the evidence: Reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual. Health Res. 2002, 12, 1284–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Health Interventions. Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-health-interventions (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Barnes, M.; Courtney, M.D.; Pratt, J.; Walsh, A.M. School-based youth health nurses: Roles, responsibilities, challenges, and rewards. Public Health Nurs. 2004, 21, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valli, G.P.; Cogo, A.L.P. School blogs about sexuality: An exploratory documentary study. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2013, 34, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beserra, E.P.; da Pinheiro, P.N.C.; Barroso, M.G.T. Educative action of nurse in the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases: An investigation with the adolescents. Esc. Anna Nery 2008, 12, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bersamin, M.; Paschall, M.J.; Fisher, D.A. Oregon school-based health centers and sexual and contraceptive behaviors among adolescents. J. Sch. Nurs. 2018, 34, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandahl, M.; Rosenblad, A.; Stenhammar, C.; Tydén, T.; Westerling, R.; Larsson, M.; Oscarsson, M.; Andrae, B.; Dalianis, T.; Nevéus, T. School-based intervention for the prevention of HPV among adolescents: A cluster randomised controlled study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, M.; Purcell, C.; Elliott, L.; Bailey, J.V.; Simpson, S.A.; McDaid, L.; Moore, L.; Mitchell, K.R. Peer-to-peer sharing of social media messages on sexual health in a school-based intervention: Opportunities and challenges identified in the STASH feasibility trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e20898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyn, K.K.; Darling-Fisher, C.; Pardee, M.; Ronis, D.L.; Felicetti, I.L.; Saftner, M.A. Improving sexual risk communication with adolescents using event history calendars. J. Sch. Nurs. 2012, 28, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Enah, C.; Piper, K.; Moneyham, L. Qualitative evaluation of the relevance and acceptability of a web-based HIV prevention game for rural adolescents. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 30, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Richards, S.D.; Mendelson, E.; Flynn, G.; Messina, L.; Bushley, D.; Halpern, M.; Amesty, S.; Stonbraker, S. Evaluation of a comprehensive sexuality education program in La Romana, Dominican Republic. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragão, J.M.N.; do Gubert, F.A.; Torres, R.A.M.; da Silva, A.S.R.; Vieira, N.F.C. The use of facebook in health education: Perceptions of adolescent students. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018, 71, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Soares, S.M.; Amaral, M.A.; Silva, L.B.; Silva, P.A.B. Workshops on sexuality in adolescence: Revealing voices, unveiling views student’s of the medium teaching glances. Esc. Anna Nery 2008, 12, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henderson, M.; Wight, D.; Raab, G.M.; Abraham, C.; Parkes, A.; Scott, S.; Hart, G. Impact of a Theoretically Based Sex Education Programme (SHARE) delivered by teachers on NHS registered conceptions and terminations: Final results of cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2007, 334, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tucker, J.S.; Fitzmaurice, A.E.; Imamura, M.; Penfold, S.; Penney, G.C.; Van Teijlingen, E.; Shucksmith, J.; Philip, K.L. The effect of the national demonstration project healthy respect on teenage sexual health behaviour. Eur. J. Public Health 2007, 17, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wight, D.; Raab, G.M.; Henderson, M.; Abraham, C.; Buston, K.; Hart, G.; Scott, S. Limits of teacher delivered sex education: Interim behavioural outcomes from randomised trial. BMJ 2002, 324, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serowoky, M.L.; George, N.; Yarandi, H. Using the program logic model to evaluate ¡Cuídate!: A sexual health program for latino adolescents in a school-based health center. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2015, 12, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarruel, A.M.; Jemmott, J.B.; Jemmott, L.S. A randomized controlled trial testing an HIV Prevention Intervention for Latino Youth. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2006, 160, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Villarruel, A.M.; Zhou, Y.; Gallegos, E.C.; Ronis, D.L. Examining long-term effects of cuídate-a sexual risk reduction program in Mexican Youth. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2010, 27, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salam, R.A.; Das, J.K.; Lassi, Z.S.; Bhutta, Z.A. Adolescent health interventions: Conclusions, evidence gaps, and research priorities. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, S88–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Souza, V.; Gazzinelli, M.F.; Soares, A.N.; Fernandes, M.M.; de Oliveira, R.N.G.; da Fonseca, R.M.G.S. The game as strategy for approach to sexuality with adolescents: Theoretical-methodological reflections. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2017, 70, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giovanelli, A.; Ozer, E.M.; Dahl, R.E. Leveraging technology to improve health in adolescence: A developmental science perspective. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, S7–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L’Engle, K.L.; Mangone, E.R.; Parcesepe, A.M.; Agarwal, S.; Ippoliti, N.B. Mobile phone interventions for adolescent sexual and reproductive health: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20160884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McNall, M.A.; Lichty, L.F.; Mavis, B. The impact of school-based health centers on the health outcomes of middle school and high school students. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1604–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewin, D.; Koren, A.; Morgan, B.; Shipley, S.; Hardy, R.L. Behind closed doors. J. Sch. Nurs. 2014, 30, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J.; Strange, V.; Allen, E.; Copas, A.; Johnson, A.; Bonell, C.; Babiker, A.; Oakley, A. The Long-Term Effects of a Peer-Led Sex Education Programme (RIPPLE): A cluster randomised trial in schools in England. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denford, S.; Abraham, C.; Campbell, R.; Busse, H. A Comprehensive review of reviews of school-based interventions to improve sexual-health. Health Psychol. Rev. 2017, 11, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemmott, J.B.; Jemmott, L.S.; O’Leary, A.; Ngwane, Z.; Lewis, D.A.; Bellamy, S.L.; Icard, L.D.; Carty, C.; Heeren, G.A.; Tyler, J.C.; et al. HIV/STI risk-reduction intervention efficacy with South African adolescents over 54 months. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lieberman, L.D.; Gray, H.; Wier, M.; Fiorentino, R.; Maloney, P. Long-term outcomes of an abstinence-based, small-group pregnancy prevention program in New York City Schools. Fam. Plann. Perspect. 2000, 32, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonczak, H.S.; Abbott, R.D.; Hawkins, J.D.; Kosterman, R.; Catalano, R.F. Effects of the seattle social development project on sexual behavior, pregnancy, birth, and sexually transmitted disease outcomes by age 21 Years. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2002, 156, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Domitrovich, C.E.; Durlak, J.A.; Staley, K.C.; Weissberg, R.P. Social-emotional competence: An essential factor for promoting positive adjustment and reducing risk in school children. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhassan, R.K.; Abdul-Fatawu, A.; Adzimah-Yeboah, B.; Nyaledzigbor, W.; Agana, S.; Mwini-Nyaledzigbor, P.P. Determinants of Use of Mobile Phones for Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) education and prevention among adolescents and young adult population in Ghana: Implications of public health policy and interventions design. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, M.A.; da Fonseca, R.M.G.S. Between desire and fear: Female adolescents’ social representation on sexual initiation. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2006, 40, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aventin, Á.; Lohan, M.; O’Halloran, P.; Henderson, M. Design and development of a film-based intervention about teenage men and unintended pregnancy: Applying the medical research council framework in practice. Eval. Program Plann. 2015, 49, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beserra, E.P.; Sousa, L.B.; Cardoso, V.P.; Alves, M.D.S. Perception of adolescents about the life activity “express sexuality”. Rev. Pesqui. Cuid. Fundam. Online 2017, 9, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beserra, E.P.; de Araújo, M.F.M.; Barroso, M.G.T. Health promotion in transmissible diseases—An investigation among teenagers. ACTA Paul. Enferm. 2006, 19, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, E.Á.I.; Ferrari, R.A.P. Adolescents: Knowledge about sexuality before and after participating in prevention workshops. Cien. Saude Colet. 2009, 14, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carvalho, A.M.; Rodrigues, C.S.; Medrado, K.S. Workshop in human sexuality with adolescents. Estud. Psicol. 2005, 10, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Arcos, L.D.C.; Benavides-Torres, R.A.; López-Rosales, F.; Onofre-Rodríguez, D.J.; Valdez-Montero, C.; Maas-Góngora, L. The effect of an internet-based intervention designed to reduce HIV/AIDS sexual risk among mexican adolescents. AIDS Care 2016, 28, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, J.B.; Whitaker-Brown, C.; Neely, T.; Kennedy, A.; Okoro, F. Mobile phone, social media usage, and perceptions of delivering a social media safer sex intervention for adolescents: Results from two countries. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2019, 10, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cornelius, J.B.; St. Lawrence, J.S.; Howard, J.C.; Shah, D.; Poka, A.; McDonald, D.; White, A.C. Adolescents’ perceptions of a mobile cell phone text messaging-enhanced intervention and development of a mobile cell phone-based HIV prevention intervention. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2012, 17, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Denny, S.; Robinson, E.; Lawler, C.; Bagshaw, S.; Farrant, B.; Bell, F.; Dawson, D.; Nicholson, D.; Hart, M.; Fleming, T.; et al. Association between availability and quality of health services in schools and reproductive health outcomes among students: A multilevel observational study. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, e14–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L.; Ross, B.; Caines, T.; Howorth, P. A School-Based HIV/AIDS prevention education program: Outcomes of peer-led versus community health nurse-led interventions. J. Pract. Nurs. 1998, 42, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, L.; Henderson, M.; Nixon, C.; Wight, D. Has untargeted sexual health promotion for young people reached its limit? A quasi-experimental study. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2013, 67, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Fonseca, A.D.; Gomes, V.L.D.O.; Teixeira, K.C. Perception of adolescents about an educative action in sexual orientation conducted by nursing academics’. Esc. Anna Nery 2010, 14, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Freitas, K.R.; Dias, S.M.Z. Teenagers’ perceptions regarding their sexuality. Texto Context. Enferm. 2010, 19, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- French, R.S.; McCarthy, O.; Baraitser, P.; Wellings, K.; Bailey, J.V.; Free, C. Young people’s views and experiences of a mobile phone texting intervention to promote safer sex behavior. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2016, 4, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallegos, E.C.; Villarruel, A.M.; Loveland-Cherry, C.; Ronis, D.L.; Yan Zhou, M. Intervención para reducir riesgo en conductas sexuales de adolescentes: Un ensayo aleatorizado y controlado. Salud Publica Mex. 2008, 50, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Golbasi, Z.; Taskin, L. Evaluation of school-based reproductive health education program for adolescent girls. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2009, 21, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubert, F.A.; dos Santos, A.C.L.; Aragão, K.A.; Pereira, D.C.R.; Vieira, N.F.C.; Pinheiro, P.N.C. Educational technology in the school context: Strategy for health education in a public school in fortaleza-CE. Rev. Eletronica Enferm. 2009, 11, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hatami, M.; Kazemi, A.; Mehrabi, T. Effect of peer education in school on sexual health knowledge and attitude in girl adolescents. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2015, 4, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, N.E.; Schaar, G. Impact of an educational text message intervention on adolescents’ knowledge and high-risk behaviors. Compr. Child. Adolesc. Nurs. 2018, 41, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemmott, J.B., III; Sweet Jemmott, L.; Fong, G.T. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African American Adolescents. JAMA 1998, 279, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levandowski, D.C.; Schmidt, M.M. Workshop addressing sexuality and dating directed to adolescents. Paid 2010, 20, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madeni, F.; Horiuchi, S.; Iida, M. Evaluation of a reproductive health awareness program for adolescence in urban Tanzania-A quasi-experimental pre-test post-test research. Reprod. Health 2011, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moodi, M.; Shahnazi, H.; Sharifirad, G.-R.; Zamanipour, N. Evaluating puberty health program effect on knowledge increase among female intermediate and high school students in Birjand, Iran. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2013, 2, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Okanlawon, F.A.; Asuzu, M.C. Secondary school adolescents’ perception of risk in sexual behaviour in rural community of Oyo State, Nigeria. J. Community Med. Prim. Health Care 2013, 24, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira, R.N.G.; Gessner, R.; de Souza, V.; da Fonseca, R.M.G.S. Limits and possibilities of an online game for building adolescents’ knowledge of sexuality. Cien. Saude Colet. 2016, 21, 2383–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rani, M.; Sheoran, P.; Kumar, Y.; Singh, N. Evaluating the effectiveness of pubertal preparedness program in terms of knowledge and attitude regarding pubertal changes among pre-adolescent girls. J. Fam. Reprod. Health 2016, 10, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Rokicki, S.; Cohen, J.; Salomon, J.A.; Fink, G. Impact of a text-messaging program on adolescent reproductive health: A cluster–randomized trial in Ghana. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.P.; de Alencar, A.B.; Lima, S.V.M.A.; Silva, G.M.; Carvalho, C.M.D.L.; da Farre, A.G.M.C.; de Sousa, L.B. Educational pre-carnival on sexually transmitted infections with school adolescents. Rev. Enferm. UFPE Line 2017, 11, 5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siegel, D.M.; Aten, M.J.; Roghmann, K.J.; Enaharo, M. Early effects of a school-based human immunodeficiency virus infection and sexual risk prevention intervention. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1998, 152, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J.; Strange, V.; Forrest, S.; Oakley, A.; Copas, A.; Allen, E.; Babiker, A.; Black, S.; Ali, M.; Monteiro, H.; et al. Pupil-Led Sex Education in England (RIPPLE Study): Cluster-randomised intervention trial. Lancet 2004, 364, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.; Gutierrez, J.P.; Torres, P.; Bertozzi, S.M. HIV prevention in Mexican schools: Prospective randomised evaluation of intervention. BMJ 2006, 332, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yakubu, I.; Garmaroudi, G.; Sadeghi, R.; Tol, A.; Yekaninejad, M.S.; Yidana, A. Assessing the impact of an educational intervention program on sexual abstinence based on the health belief model amongst adolescent girls in Northern Ghana, a cluster randomised control trial. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loureiro, F.; Ferreira, M.; Sarreira-de-Oliveira, P.; Antunes, V. Interventions to Promote a Healthy Sexuality among School Adolescents: A Scoping Review. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1155. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111155

Loureiro F, Ferreira M, Sarreira-de-Oliveira P, Antunes V. Interventions to Promote a Healthy Sexuality among School Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021; 11(11):1155. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111155

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoureiro, Fernanda, Margarida Ferreira, Paula Sarreira-de-Oliveira, and Vanessa Antunes. 2021. "Interventions to Promote a Healthy Sexuality among School Adolescents: A Scoping Review" Journal of Personalized Medicine 11, no. 11: 1155. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111155

APA StyleLoureiro, F., Ferreira, M., Sarreira-de-Oliveira, P., & Antunes, V. (2021). Interventions to Promote a Healthy Sexuality among School Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 11(11), 1155. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111155