Quantitative Ultrasound Radiomics for Predicting and Monitoring Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategies

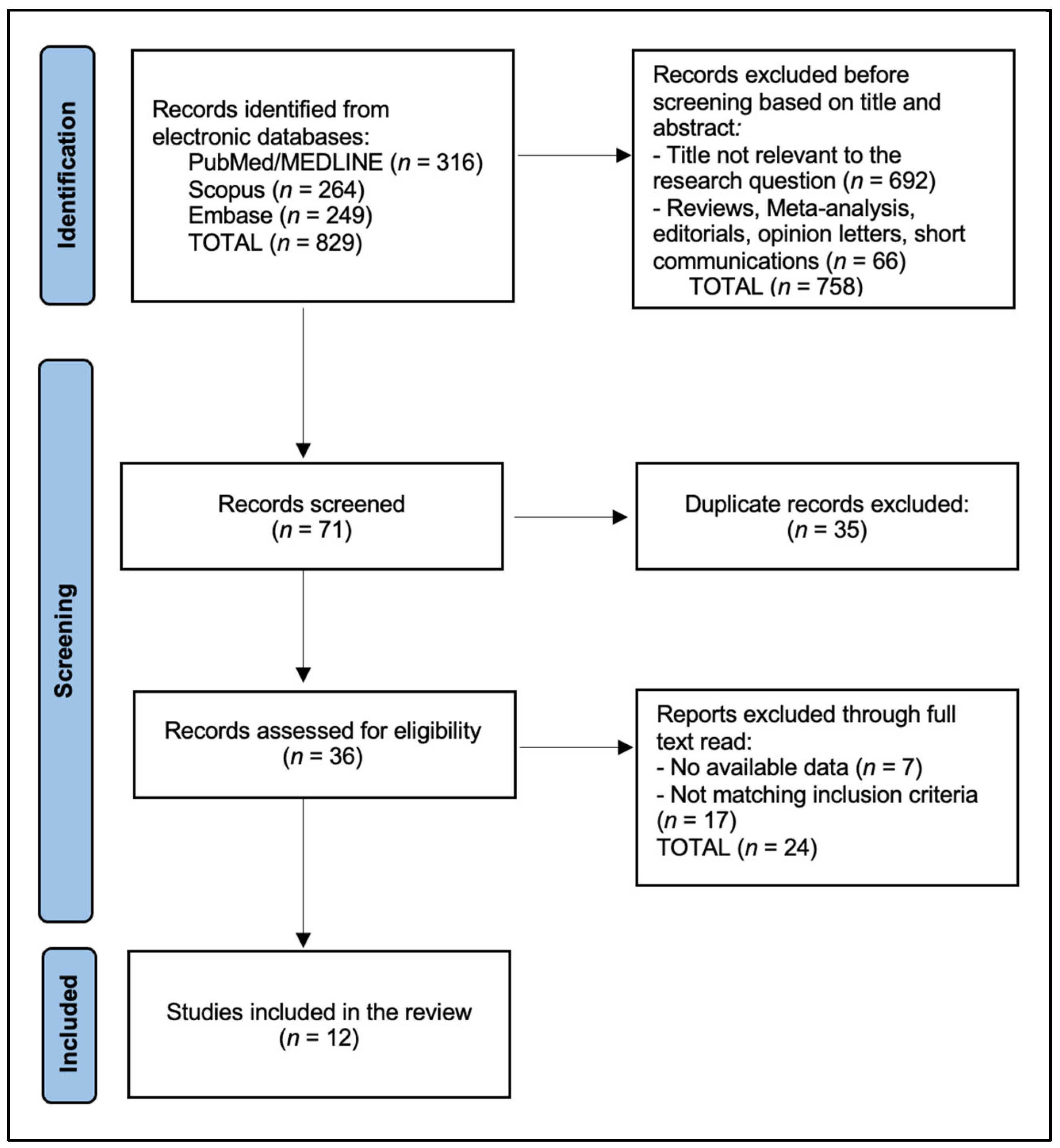

2.4. Selection Process

2.5. Risk of Bias

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Korde, L.A.; Somerfield, M.R.; Carey, L.A.; Crews, J.R.; Denduluri, N.; Hwang, E.S.; Khan, S.A.; Loibl, S.; Morris, E.A.; Perez, A.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy, Endocrine Therapy, and Targeted Therapy for Breast Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1485–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gradishar, W.J.; Moran, M.S.; Abraham, J.; Abramson, V.; Aft, R.; Agnese, D.; Allison, K.H.; Anderson, B.; Bailey, J.; Burstein, H.J.; et al. Breast Cancer, Version 3.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2024, 22, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortazar, P.; Zhang, L.; Untch, M.; Mehta, K.; Costantino, J.P.; Wolmark, N.; Bonnefoi, H.; Cameron, D.; Gianni, L.; Valagussa, P.; et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: The CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet 2014, 384, 164–172, Erratum in Lancet 2019, 393, 986. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32772-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conforti, F.; Pala, L.; Sala, I.; Oriecuia, C.; De Pas, T.; Specchia, C.; Graffeo, R.; Pagan, E.; Queirolo, P.; Pennacchioli, E.; et al. Evaluation of pathological complete response as surrogate endpoint in neoadjuvant randomised clinical trials of early stage breast cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2021, 375, e066381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reig, B.; Lewin, A.A.; Du, L.; Heacock, L.; Toth, H.K.; Heller, S.L.; Gao, Y.; Moy, L. Breast MRI for Evaluation of Response to Neoadjuvant Therapy. Radiographics 2021, 41, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oelze, M.L.; Mamou, J. Review of Quantitative Ultrasound: Envelope Statistics and Backscatter Coefficient Imaging and Contributions to Diagnostic Ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2016, 63, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lizzi, F.L.; Astor, M.; Feleppa, E.J.; Shao, M.; Kalisz, A. Statistical framework for ultrasonic spectral parameter imaging. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 1997, 23, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizzi, F.L.; Ostromogilsky, M.; Feleppa, E.J.; Rorke, M.C.; Yaremko, M.M. Relationship of ultrasonic spectral parameters to features of tissue microstructure. IEEE Trans. Ultrason Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 1987, 34, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.Y.; Cao, L.H.; Wang, J.W.; Zheng, W.; Chen, Y.; Feng, Z.Z.; Li, A.H.; Zhou, J.H. Ultrasonic spectrum analysis for in vivo characterization of tumor microstructural changes in the evaluation of tumor response to chemotherapy using diagnostic ultrasound. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vlad, R.M.; Brand, S.; Giles, A.; Kolios, M.C.; Czarnota, G.J. Quantitative ultrasound characterization of responses to radiotherapy in cancer mouse models. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 2067–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osapoetra, L.O.; Chan, W.; Tran, W.; Kolios, M.C.; Czarnota, G.J. Comparison of methods for texture analysis of QUS parametric images in the characterization of breast lesions. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Jiang, S.; Li, T.; Chen, F.; Lei, J.; Li, R.; Xi, L.; Guo, S. Intra- and peritumoral radiomics features based on multicenter automatic breast volume scanner for noninvasive and preoperative prediction of HER2 status in breast cancer: A model ensemble research. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Janssen, L.M.; den Dekker, B.M.; Gilhuijs, K.G.A.; van Diest, P.J.; van der Wall, E.; Elias, S.G. MRI to assess response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer subtypes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Breast Cancer 2022, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jin, J.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, B. Diagnostic Performance of Strain and Shear Wave Elastography for the Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Ultrasound Med. 2022, 41, 2459–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerussi, A.; Hsiang, D.; Shah, N.; Mehta, R.; Durkin, A.; Butler, J.; Tromberg, B.J. Predicting response to breast cancer neoadjuvant chemotherapy using diffuse optical spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 4014–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tran, W.T.; Childs, C.; Chin, L.; Slodkowska, E.; Sannachi, L.; Tadayyon, H.; Watkins, E.; Wong, S.L.; Curpen, B.; El Kaffas, A.; et al. Multiparametric monitoring of chemotherapy treatment response in locally advanced breast cancer using quantitative ultrasound and diffuse optical spectroscopy. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 19762–19780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tadayyon, H.; Sannachi, L.; Gangeh, M.; Sadeghi-Naini, A.; Tran, W.; Trudeau, M.E.; Pritchard, K.; Ghandi, S.; Verma, S.; Czarnota, G.J. Quantitative ultrasound assessment of breast tumor response to chemotherapy using a multi-parameter approach. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 45094–45111, Erratum in Oncotarget 2017, 8, 35481. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.18068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi-Naini, A.; Sannachi, L.; Tadayyon, H.; Tran, W.T.; Slodkowska, E.; Trudeau, M.; Gandhi, S.; Pritchard, K.; Kolios, M.C. Chemotherapy-Response Monitoring of Breast Cancer Patients Using Quantitative Ultrasound-Based Intra-Tumour Heterogeneities. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannachi, L.; Gangeh, M.; Tadayyon, H.; Sadeghi-Naini, A.; Gandhi, S.; Wright, F.C.; Slodkowska, E.; Curpen, B.; Tran, W.; Czarnota, G.J. Response monitoring of breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy using quantitative ultrasound, texture, and molecular features. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- DiCenzo, D.; Quiaoit, K.; Fatima, K.; Bhardwaj, D.; Sannachi, L.; Gangeh, M.; Sadeghi-Naini, A.; Dasgupta, A.; Kolios, M.C.; Trudeau, M.; et al. Quantitative ultrasound radiomics in predicting response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced breast cancer: Results from multi-institutional study. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 5798–5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Quiaoit, K.; DiCenzo, D.; Fatima, K.; Bhardwaj, D.; Sannachi, L.; Gangeh, M.; Sadeghi-Naini, A.; Dasgupta, A.; Kolios, M.C.; Trudeau, M.; et al. Quantitative ultrasound radiomics for therapy response monitoring in patients with locally advanced breast cancer: Multi-institutional study results. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dasgupta, A.; Brade, S.; Sannachi, L.; Quiaoit, K.; Fatima, K.; DiCenzo, D.; Osapoetra, L.O.; Saifuddin, M.; Trudeau, M.; Gandhi, S.; et al. Quantitative ultrasound radiomics using texture derivatives in prediction of treatment response to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced breast cancer. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 3782–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dobruch-Sobczak, K.; Piotrzkowska-Wróblewska, H.; Klimoda, Z.; Secomski, W.; Karwat, P.; Markiewicz-Grodzicka, E.; Kolasińska-Ćwikła, A.; Roszkowska-Purska, K.; Litniewski, J. Monitoring the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer using ultrasound scattering coefficient: A preliminary report. J. Ultrason. 2019, 19, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sannachi, L.; Osapoetra, L.O.; DiCenzo, D.; Halstead, S.; Wright, F.; Look-Hong, N. A priori prediction of breast cancer response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy using quantitative ultrasound, texture derivative and molecular subtype. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falou, O.; Sannachi, L.; Haque, M.; Czarnota, G.J.; Kolios, M. Transfer learning of pre-treatment quantitative ultrasound multi-parametric images for the prediction of breast cancer response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, A.; DiCenzo, D.; Sannachi, L.; Gandhi, S.; Pezo, R.C.; Eisen, A.; Warner, E.; Wright, F.C.; Look-Hong, N.; Sadeghi-Naini, A.; et al. Quantitative ultrasound radiomics guided adaptive neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: Early results from a randomized feasibility study. Front Oncol. 2024, 14, 1273437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Taleghamar, H.; Jalalifar, S.A.; Czarnota, G.J.; Sadeghi-Naini, A. Deep learning of quantitative ultrasound multi-parametric images at pre-treatment to predict breast cancer response to chemotherapy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gu, J.; Zhong, X.; Fang, C.; Lou, W.; Fu, P.; Woodruff, H.C.; Wang, B.; Jiang, T.; Lambin, P. Deep Learning of Multimodal Ultrasound: Stratifying the Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer Before Treatment. Oncologist 2024, 29, e187–e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, M.; Huang, Z.; Tian, H.; Mo, S.; Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Dong, F. Longitudinal Ultrasound Delta Radiomics for Early Stratified Prediction of Tumor Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer. Acad. Radiol. 2025, 32, 7119–7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Q.; Ji, Z.; Xu, N.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, T.; Ding, M.; Qu, L.; Liu, Y.; Xie, J.; Jin, F.; et al. Prediction of neoadjuvant chemotherapy efficacy in patients with HER2-low breast cancer based on ultrasound radiomics. Cancer Imaging 2025, 25, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Gao, Y.; Lu, X.; Lei, J. Ultrasound-based radiomics for early predicting response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Radiol. Med. 2024, 129, 934–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valizadeh, P.; Jannatdoust, P.; Moradi, N.; Yaghoobpoor, S.; Toofani, S.; Rafiei, N.; Moodi, F.; Ghorani, H.; Arian, A. Ultrasound-based machine learning models for predicting response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Clin. Imaging 2025, 125, 110574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Lei, P.; Zhu, X.; Li, B. MRI-based radiomics models for early predicting pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2025, 26, e70296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Luo, S.; Chen, X.; Yao, M.; Ying, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, X. Intratumoral and peritumoral ultrasound-based radiomics for preoperative prediction of HER2-low breast cancer: A multicenter retrospective study. Insights Imaging 2025, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, G.S.; Moons, K.G.M.; Dhiman, P.; Riley, R.D.; Beam, A.L.; Van Calster, B.; Ghassemi, M.; Liu, X.; Reitsma, J.B.; van Smeden, M.; et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: Updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 2024, 385, e078378, Erratum in BMJ 2024, 385, q902. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.q902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejani, A.S.; Klontzas, M.E.; Gatti, A.A.; Mongan, J.T.; Moy, L.; Park, S.H.; Kahn, C.E., Jr. CLAIM 2024 Update Panel. Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging (CLAIM): 2024 Update. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, e240300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koçak, B.; Köse, F.; Keleş, A.; Şendur, A.; Meşe, İ.; Karagülle, M. Adherence to the Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging (CLAIM): An umbrella review with a comprehensive two-level analysis. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2025, 31, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lyu, M.; Yi, S.; Li, C.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wei, Z.; Lin, H.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, C. Multimodal prediction based on ultrasound for response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple negative breast cancer. npj Precis. Onc 2025, 9, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Song, L.; Zhao, H.; Wan, X.; Peng, Y. Integrative multimodal ultrasound and radiomics for early prediction of neoadjuvant therapy response in breast cancer: A clinical study. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Study (Year) | Country/Setting | N | Design and Timepoints | QUS Features/ROI | Model | Endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tran et al., 2016 [17] | Canada | 22 | Monitoring: BL, W1, W4, W8, pre-op | SI, SS, MBF ± DOSI; tumor core | Discriminant/logistic | Clinical/pathologic response |

| 2 | Tadayyon et al., 2016 [18] | Canada | 58 | Baseline + early changes: BL, W1, W4, W8 | MBF, SS, SI + textures; core + margin | SVM/FLD/KNN | Responder vs. non-responder |

| 3 | Sadeghi-Naini et al., 2017 [19] | Canada | 100 | Monitoring heterogeneity (serial) | QUS parametric maps + heterogeneity/textures; ROI NR | ML (NR) | Response vs. non-response |

| 4 | Sannachi et al., 2018 [20] | Canada | 96 | Monitoring: BL, W1, W4, W8 | QUS + texture + molecular; core ± margin | SVM (RBF) | Response class |

| 5 | DiCenzo et al., 2020 [21] | Multi-institutional | 82 | A priori (pre-treatment) | QUS radiomics; ROI NR | KNN/SVM (best reported) | Response class |

| 6 | Quiaoit et al., 2020 [22] | Multi-institutional | 59 | Monitoring: BL, W1, W4 | QUS radiomics; ROI NR | SVM-RBF/FLD/KNN | Response class |

| 7 | Dasgupta et al., 2020 [23] | Canada | 100 | A priori (pre-treatment) | QUS textures → texture-derivatives; core + margin | SVM/KNN/FLD | Response class |

| 8 | Dobruch-Sobczak et al., 2019 [24] | Poland | 10 pts/13 tumors | Monitoring (pilot) | Integrated backscatter/scattering coeff.; ROI NR | ROC analysis | Pathology-based response |

| 9 | Sannachi et al., 2023 [25] | Canada | 208 | A priori | QUS + texture-derivatives + subtype; core ± margin | ML ensemble | Response class |

| 10 | Falou et al., 2024 [26] | Canada | 174 | A priori | QUS parametric maps (core ± margin) | Transfer learning + classifier | Response class |

| 11 | Dasgupta et al., 2024 [27] | Canada | 60 accrued/56 analyzed | Randomized feasibility (BL, W1, W4) | Week-4 QUS radiomics decision support | Pragmatic (model-guided) | Decision impact + week-4 prediction |

| 12 | Taleghamar et al., 2022 [28] | Canada | 181 | A priori | DL features from QUS maps | CNN/ResNet-type | Response class |

| Study (Year) | N | ROI Used for Feature Extraction | Features in Final Model (Reported) | Pre-Treatment Performance | Earliest on-Treatment Performance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tran 2016 [17] | 22 | Tumor core | NR | NR | W1 → AUC 1.00; Sens/Spec 100/100 | Combined QUS + optical features |

| Tadayyon 2016 [18] | 58 | Core + margin | NR | NR | W1 (with BL) → Acc 70%; W4 (with BL) → Acc 80% | Best later W8 Acc 93% |

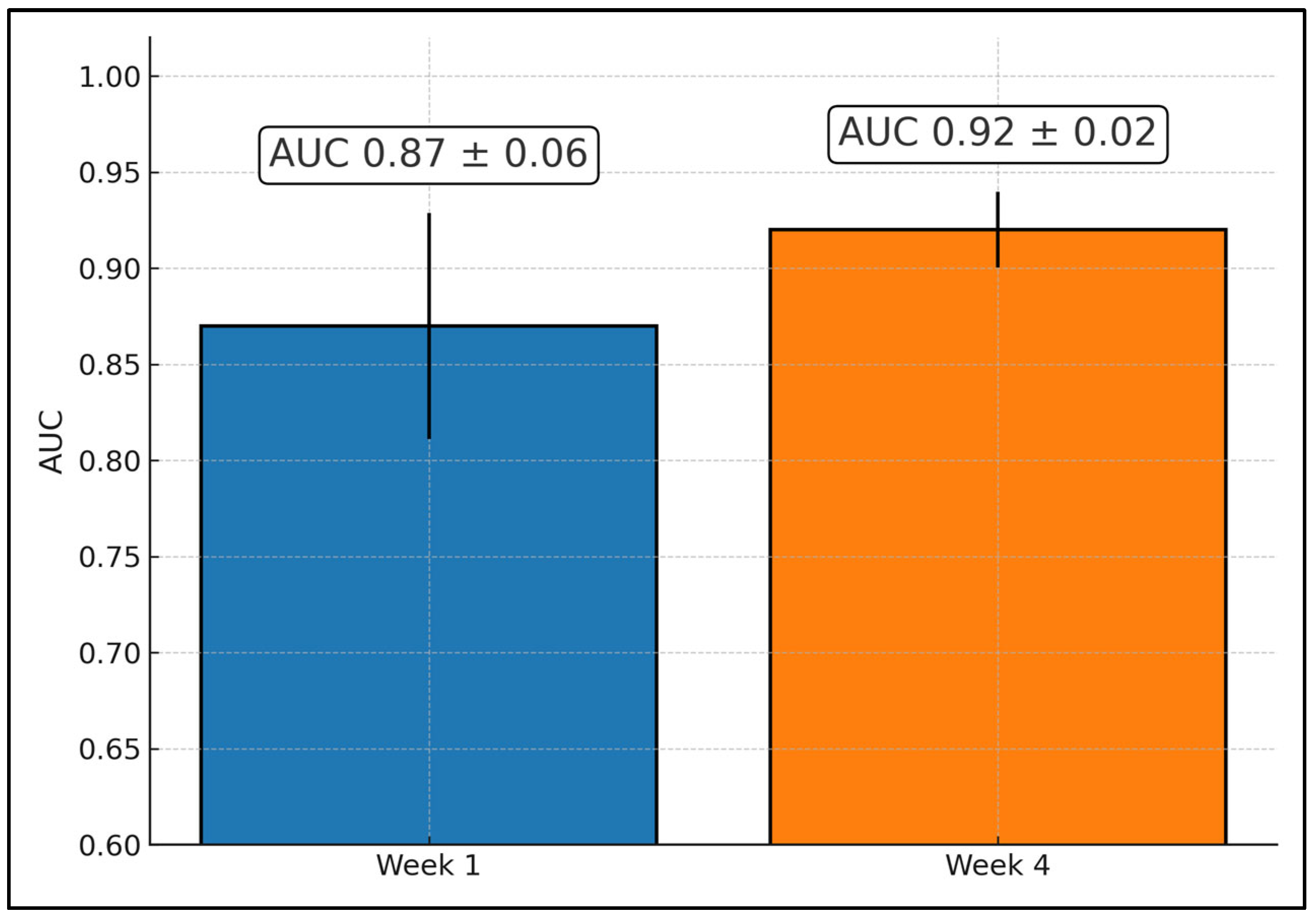

| Sadeghi-Naini 2017 [19] | 100 | ROI NR | NR | NR | W1 → AUC 0.81, Acc 76%; W4 → AUC 0.91, Acc 86% | Heterogeneity monitoring |

| Sannachi 2018 [20] | 96 | Core ± margin | NR | NR | W1 → Acc 78%; W4 → 86% | Multiclass setting |

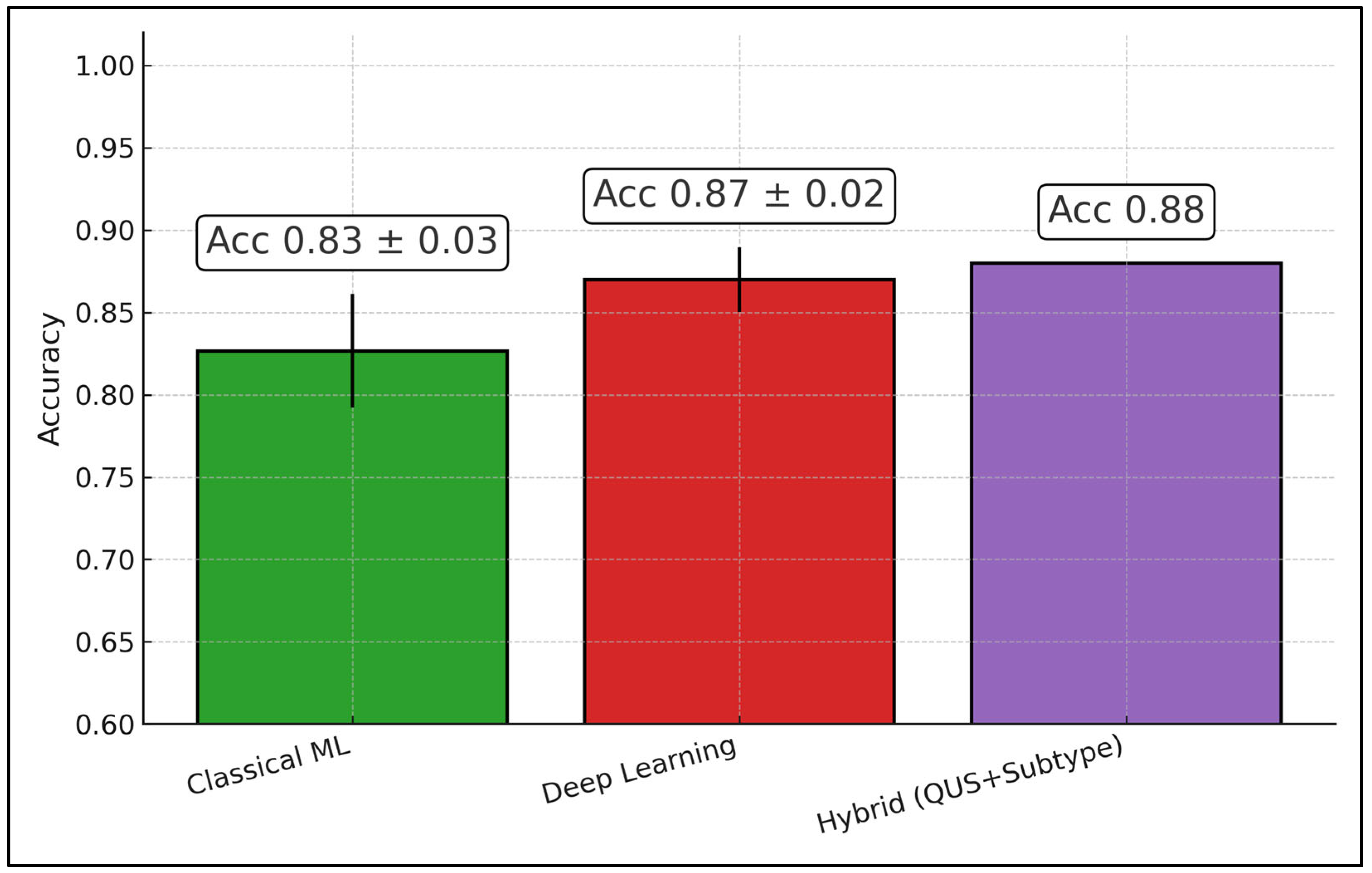

| DiCenzo 2020 [21] | 82 | ROI NR | NR | Acc 87%; Sens 91%; Spec 83% | — | Baseline only |

| Quiaoit 2020 [22] | 59 | ROI NR | NR | Acc 76%; AUC 0.68 | W4 → Acc 81%; AUC 0.87 | Multi-institutional |

| Dasgupta 2020 [23] | 100 | Core + margin | NR | Acc 82%; AUC 0.86 | — | Texture-derivatives |

| Dobruch-Sobczak 2019 [24] | 10/13 | ROI NR | — | NR | ROC discrimination reported | Pilot |

| Sannachi 2023 [25] | 208 | Core ± margin | NR | Acc 86%; AUC 0.90 | — | Adds subtype |

| Falou 2024 [26] | 174 | Core ± margin | NR | Balanced Acc 86% | — | Transfer learning |

| Dasgupta 2024 [27] | 60/56 | Tumor ROI + serial mapping | Model used 4 texture features (week-4) | — | Week-4 accuracy ~97–98% | Randomized feasibility |

| Taleghamar 2022 [28] | 181 | Tumor ROI (QUS maps) | NR | Acc 88%; AUC 0.86 | — | Deep learning |

| Study | Sites/External Validation | Response Ground Truth (How “Response” was Defined) | RF Acquisition and Calibration (System/Probe/Freq/Sampling; Normalization and Attenuation) | Validation and Class Imbalance Handling | Survival/Prognosis Link | Decision Impact/Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tran et al., 2016 [17] | Single site; no external set | Responder = pCR or >50% decrease in tumor size by RECIST 1.1; NR = stable/progressive or <50% decrease | Sonix RP (Ultrasonix) + L14-5/60; center ~7 MHz; RF digitization 40 MHz (8-bit); panoramic tumor sweep; reference phantom normalization; −6 dB bandwidth linear fit (MBF/SI/SS); Hamming window; ~80% axial overlap | ROC analysis and multivariate logistic regression on paired QUS+DOSI parameters; no external CV; per-timepoint AUC reporting | Not reported | Methods precedent for combined QUS + diffuse optical spectroscopy monitoring |

| Tadayyon et al., 2016 [18] | Single site; no external set | “Ultimate clinical & pathological response” used to label R/NR (final surgical pathology + clinical shrinkage) | Sonix RP + L14-5/60; center ~7 MHz; RF 40 MHz; sliding window 2 × 2 mm; phantom-based spectral normalization; attenuation coefficient estimate (ACE) applied; features include MBF/SS/SI/SAS/ASD/AAC | Leave-one-patient-out cross-validation at subject level; k-NN/FLD/SVM models; feature selection (sequential forward) | KM separation significant at week-1 and week-4 (p ≈ 0.035 and p ≈ 0.027) | Early-change feasibility template (baseline + W1/W4/W8) |

| Sadeghi-Naini et al., 2017 [19] | Single site; no external set | Monitoring heterogeneity; clinical/pathological responder vs. non-responder categories (as defined in cohort) | RF-based QUS parametric maps; reference-phantom-normalized spectra; textures from QUS maps; (group’s standard Sonix RP platform) | Descriptive discrimination of intra-tumor heterogeneity; internal cross-validation for imaging signatures | Not reported | Emphasis on intra-tumor heterogeneity signals during NAC |

| Sannachi et al., 2018 [20] | Single site; no external set | Three-class response (CR/PR/NR) from clinical & pathological assessment after NAC | Sonix RP + L14-5/60; center ~7 MHz; RF 40 MHz; 2 × 2 mm analysis window; ~92% axial/lateral overlap; phantom normalization; ACE applied before spectral fit | Multiclass SVM (RBF); subject-level cross-validation; molecular subtype integrated with QUS features | Not reported | Schedules W1/W4/W8 established for serial QUS monitoring |

| DiCenzo et al., 2020 [21] | Multi-institution (4 sites); no held-out external cohort beyond multi-site pooling | Binary R/NR at surgery from pathology (cohort-standard composite) | RF-enabled clinical systems across centers (Sonix RP and GE platforms used across network); phantom-based normalization; attenuation correction applied prior to spectral parameterization | Cross-validation on pooled multi-site set; K-NN best among tested models; feature selection to limit dimensionality | Not reported | Demonstrated a priori prediction feasibility across sites |

| Quiaoit et al., 2020 [22] | Multi-institution (2 systems used); no separate held-out site | Modified dichotomous criterion: responder = pCR or “very low” cellularity or >30% size decrease; non-responder = PD or <30% decrease | Two systems: Sonix RP + L14-5/60 (center ~6.3 MHz; RF 40 MHz) and GE LOGIQ E9 + ML6-15 (center ~7 MHz; RF 50 MHz); phantom normalization per-system; ACE via reference phantom method; −6 dB bandwidth fit for MBF/SI/SS | Leave-one-out CV at subject level; random undersampling to balance classes for FLD/SVM (K-NN also reported on unbalanced data); sequential forward feature selection | Not reported | Early-monitoring generalization with mixed hardware; standardized normalization across devices |

| Dasgupta et al., 2020 [23] | Single large cohort; no external site | Pre-treatment binary R/NR from clinical/pathological endpoint | Sonix RP; linear probe; center ~6.5–7 MHz; RF 40 MHz; QUS parametric maps (MBF/SS/SI + BSC model) → textures → texture-derivatives; phantom normalization; attenuation compensation applied | Cross-validated training/evaluation with repeated sub-sampling for stability; SVM/K-NN/FLD evaluated (SVM best in paper); leakage avoided by subject-level splits | Reported that model-predicted groups mirrored actual RFS in follow-up (prognostic separation) | A priori baseline model for decision support prior to NAC start |

| Dobruch-Sobczak et al., 2019 [24] | Single site pilot; no external set | Pathology after NAC: cellularity reduction and residual size; R/NR derived from histology | RF acquisition with clinical US; integrated backscatter/scattering coefficient computed; serial scans before and ~1 week after each NAC cycle; phantom-referenced estimation | ROC-based discrimination of early cycles; small N; no formal ML CV | Early cycles predicted final outcome (AUC ~0.82 by dose-2/3 reported) | Early European feasibility using scattering coefficient framework |

| Sannachi et al., 2023 [25] | Large single site; internal train/val/test split | Baseline (pre-Tx) binary R/NR; subtype included in labeling model | RF-based QUS maps at baseline; phantom-normalized spectra; attenuation-corrected; radiomics + texture-derivatives + subtype features | Supervised ML ensemble; subject-level train/validation/test split (reported in paper); calibration assessed; CI reported | Not reported | A priori hybrid QUS+subtype approach for baseline decisioning |

| Falou et al., 2024 [26] | Single site with unseen test subset | Baseline R/NR at surgery; subgroup OS/RFS curves shown | RF-based multi-parametric QUS maps; phantom normalization; attenuation correction; transfer-learning on QUS maps | Train/validation with separate unseen test set; TL-CNN features + classical classifier; class performance by precision/recall reported | Survival curves (OS/RFS) provided by clinical groups; QUS prediction reported alongside | Implementation of transfer learning on baseline QUS maps |

| Dasgupta et al., 2024 [27] | Single-institution randomized feasibility trial | Final response at surgery; week-4 QUS model used to predict early response for adaptation | Sonix RP (L14-5/60, ~6.5 MHz) or GE LOGIQ E9 (ML6-15, ~6.9 MHz); standard RF capture; serial baseline/W1/W4; phantom normalization; attenuation-aware spectral processing | Phase-2 RCT (1:1), stratified by hormone-receptor status; observational vs. experimental (adaptive) arms; model pre-trained on prior 100-pt cohort; prospective validation (week-4 accuracy ~98% stated in manuscript) | Not a survival study; primary = feasibility and prospective predictive performance | QUS-guided adaptive NAC allowed oncologist-directed changes (e.g., early taxane, intensification, or early surgery); 3/5 predicted NR adapted → final responders |

| Taleghamar et al., 2022 [28] | Single site with internal test set | Baseline R/NR at surgery | RF-based multi-parametric QUS maps at pre-Tx; phantom normalization; attenuation-corrected spectra as DL inputs | CNN with defined train/validation/test split; reports test accuracy/AUC for held-out set | Not reported | Demonstrated deep-learning feasibility at pre-Tx for a priori prediction |

| Study (Year) [Ref.] | Patient Selection | Index Test (Feature Leakage Prevention, Blinding) | Reference Standard (Response Definition) | Flow and Timing (Intervals, Attrition) | Analysis (CV/Validation, Class Imbalance, Calibration) | Overall ROB | Key Limitation(s)/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tran 2016 [17] | SC | SC | SC | L | H | H | Single-site convenience cohort; no external validation; multivariable modeling without clear nested CV; per-timepoint modeling may inflate optimism. |

| Tadayyon 2016 [18] | SC | SC | SC | L | SC | SC | LOPO CV at patient level; sequential forward feature selection (nesting not explicitly stated); composite responder definition. |

| Sadeghi-Naini 2017 [19] | SC | SC | SC | L | SC | SC | Heterogeneity-focused monitoring; internal CV only; limited reporting of blinding and calibration. |

| Sannachi 2018 [20] | SC | SC | SC | L | SC | SC | Multiclass SVM with subject-level CV; no external validation; responder categories derived from clinical+pathologic assessment. |

| DiCenzo 2020 [21] | SC | SC | SC | L | SC | SC | Multi-institution pooling but no held-out external site; K-NN best on internal CV; AUC NR at baseline; calibration NR. |

| Quiaoit 2020 [22] | SC | SC | SC | L | SC | SC | Mixed hardware; subject-level LOOCV; random undersampling used; feature selection details limited; external validation NR. |

| Dasgupta 2020 [23] | SC | L/SC | SC | L | SC | SC | Subject-level splits stated to avoid leakage; repeated subsampling; prognostic separation noted but external validation NR; calibration limited. |

| Dobruch-Sobczak 2019 [24] | H | SC | SC | L | H | H | Small pilot; ROC analyses without formal CV; very limited sample size; high analysis ROB. |

| Sannachi 2023 [25] | SC | L/SC | SC | L | SC | SC | Internal train/validation/test split; calibration and CIs reported; still single-center without external site. |

| Falou 2024 [26] | SC | L/SC | SC | L | SC | SC | Transfer learning with separate unseen test set; external site NR; per-class metrics reported; calibration NR. |

| Dasgupta 2024 (RCT) [27] | L | L/SC | L | L | SC | SC | Prospective randomized feasibility with pretrained model; strong design for flow/timing; external multi-site validation NR; primary endpoint = decision impact. |

| Taleghamar 2022 [28] | SC | SC | SC | L | SC | SC | DL with internal train/val/test splits; external validation and calibration NR; reporting of class balance handling limited. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Putin, R.; Stana, L.G.; Ilie, A.C.; Tanase, E.; Cotoraci, C. Quantitative Ultrasound Radiomics for Predicting and Monitoring Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030425

Putin R, Stana LG, Ilie AC, Tanase E, Cotoraci C. Quantitative Ultrasound Radiomics for Predicting and Monitoring Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(3):425. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030425

Chicago/Turabian StylePutin, Ramona, Loredana Gabriela Stana, Adrian Cosmin Ilie, Elena Tanase, and Coralia Cotoraci. 2026. "Quantitative Ultrasound Radiomics for Predicting and Monitoring Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review" Diagnostics 16, no. 3: 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030425

APA StylePutin, R., Stana, L. G., Ilie, A. C., Tanase, E., & Cotoraci, C. (2026). Quantitative Ultrasound Radiomics for Predicting and Monitoring Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics, 16(3), 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16030425