Evaluation of Digital Imaging Accuracy Among Three Intraoral Scanners for Full-Arch Implant Rehabilitation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

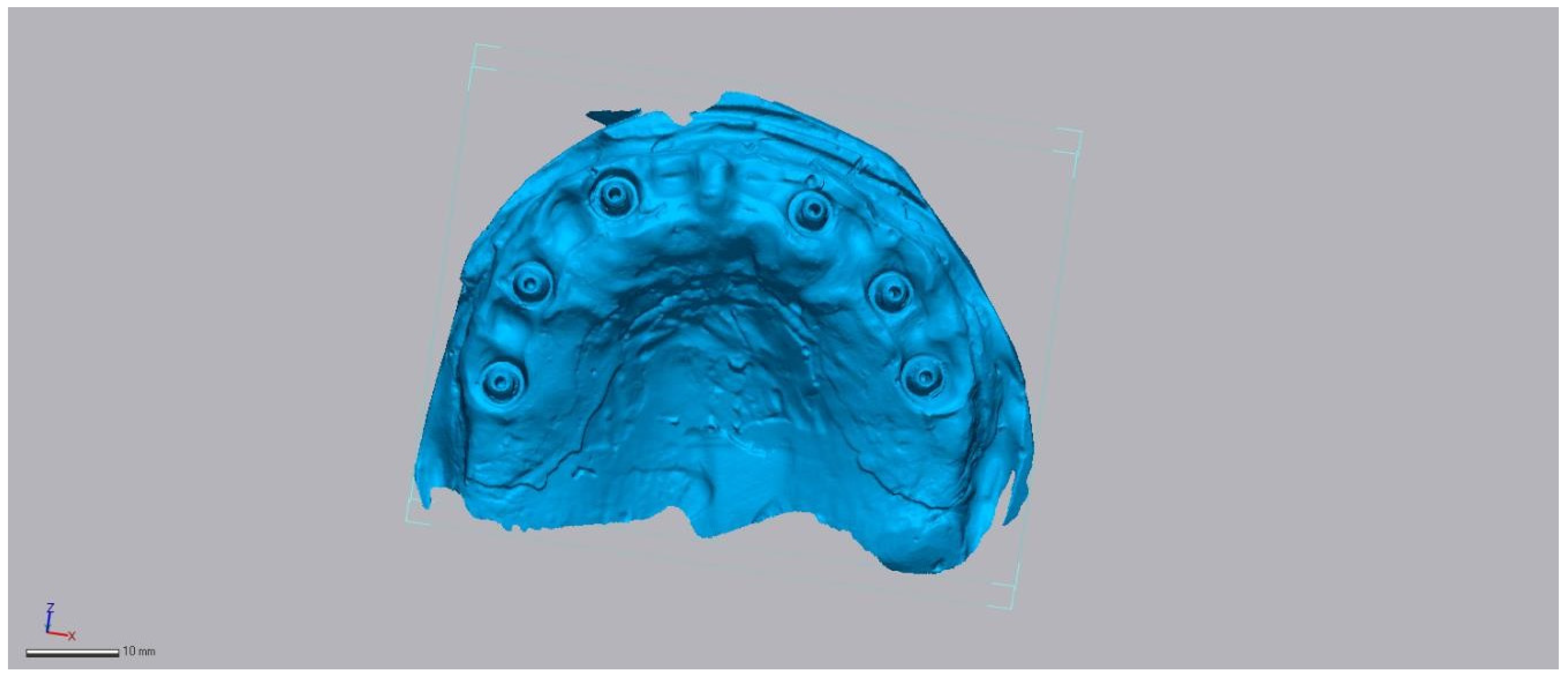

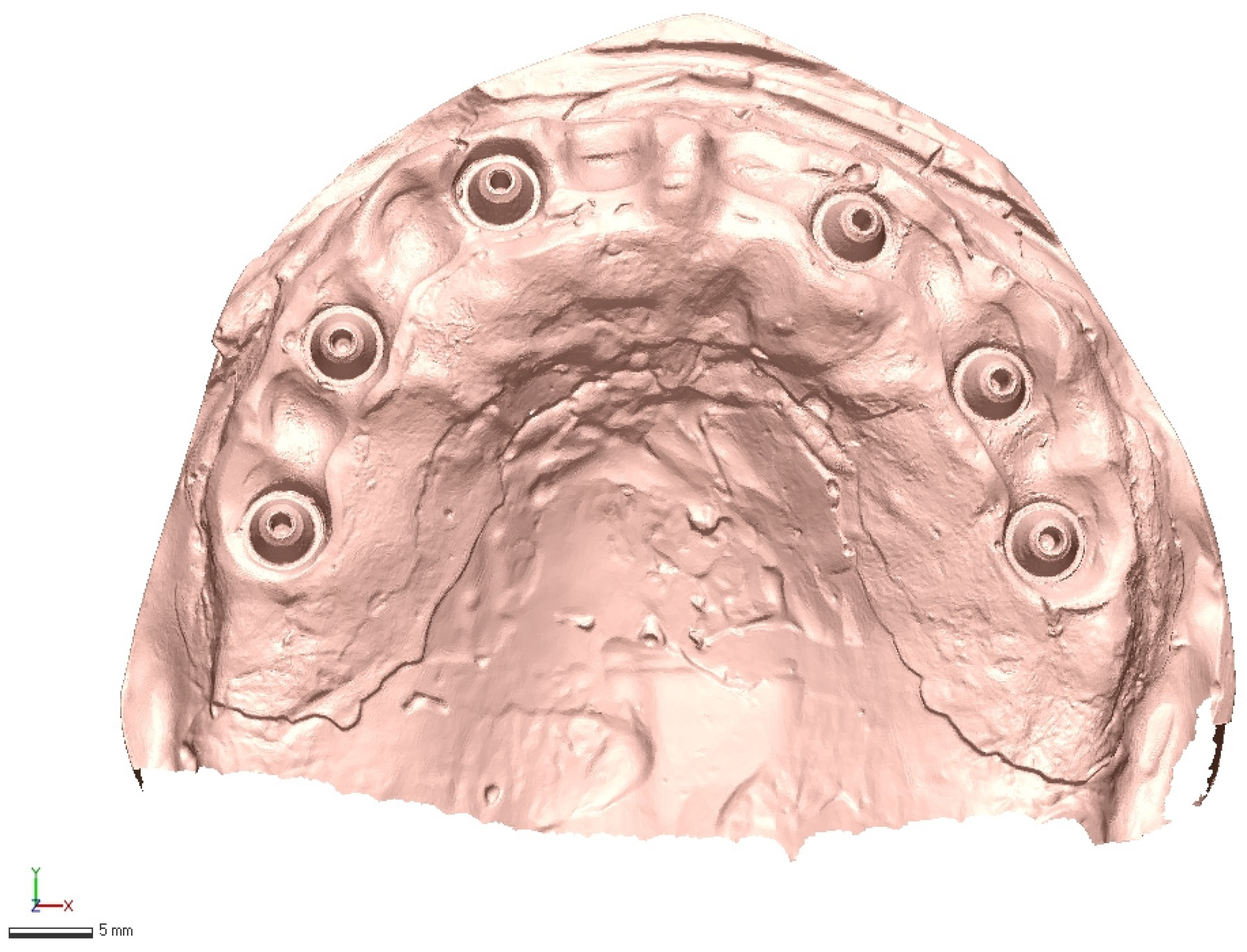

2.2. Reference Model and Ground-Truth Dataset

2.3. Test Scanners and Native Software

- •

- TRIOS Core (3Shape A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark)—10 scans, processed with 3Shape software (version 24.1).

- •

- Medit i700 (Medit Corp., Seoul, Republic of Korea)—10 scans, processed with Medit Link software (version 3.4.5).

- •

- Primescan (Dentsply Sirona, Bensheim, Germany)—10 scans, processed with CEREC software (version 5.3.2).

2.4. Operators and Environment

2.5. Scanning Protocol

- Capture of the gingival mask and peri-implant soft tissues;

- Recording of the six multi-unit analogs;

- A second pass with scan bodies attached, enabling three-dimensional capture of implant axes and positions.

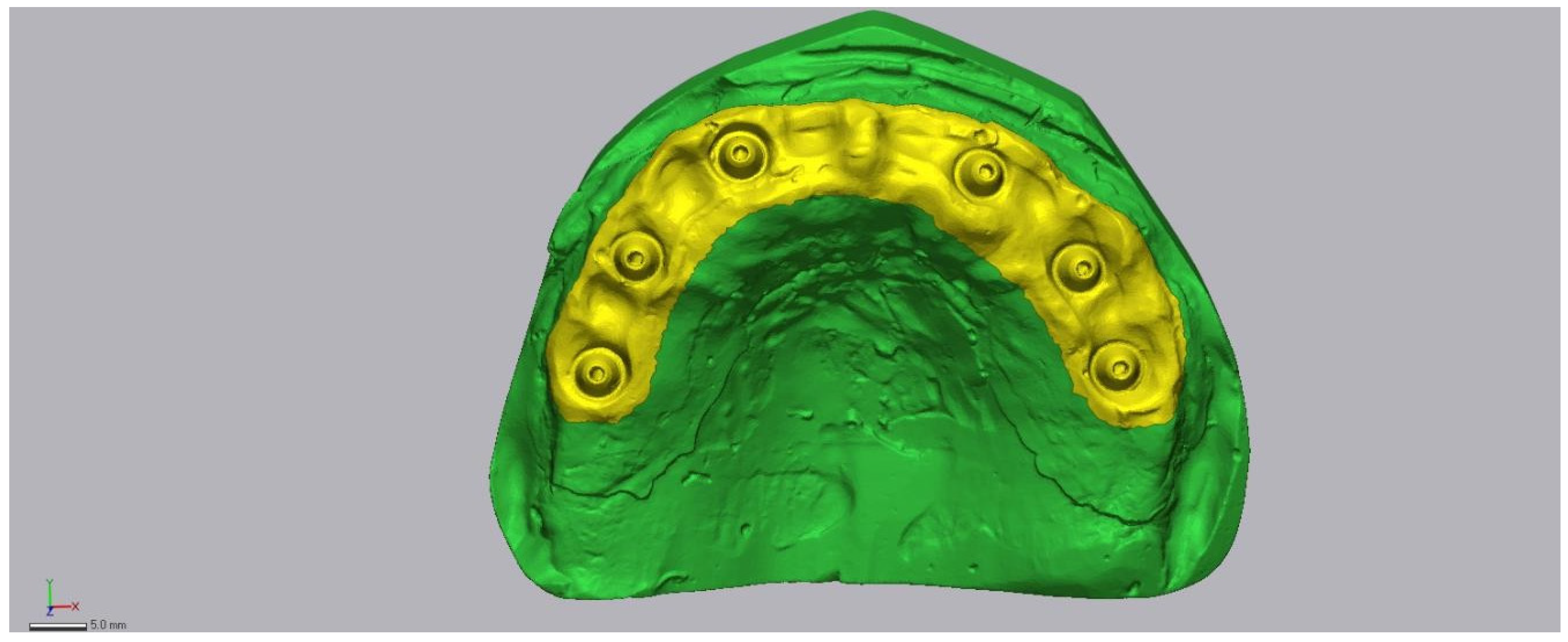

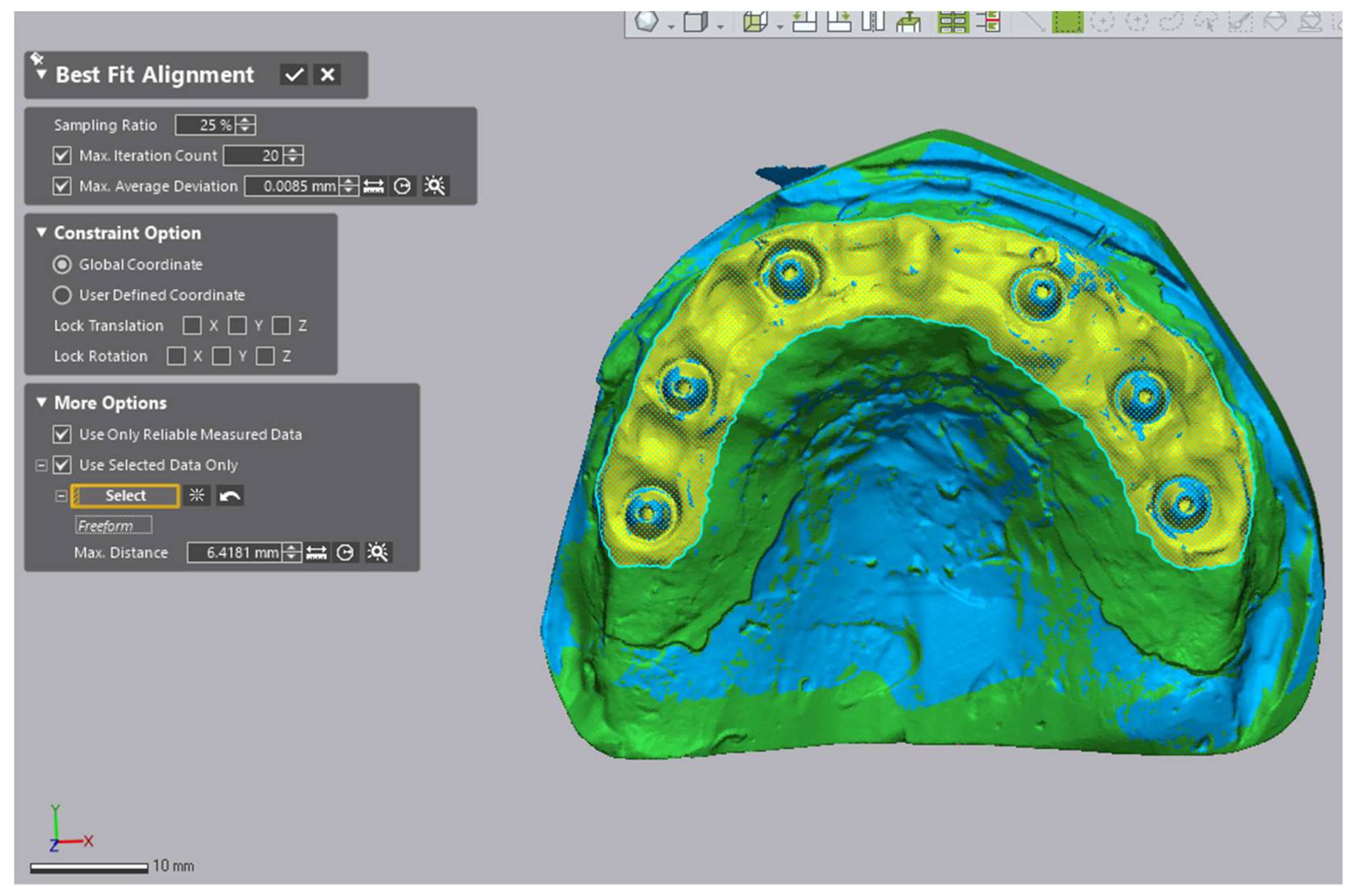

2.6. Region of Interest and Alignment Strategy

- (1)

- initial rough alignment, followed by

- (2)

- an iterative closest point (ICP) best-fit restricted to the predefined peri-implant Region of Interest (ROI) (Figure 6).

2.7. Accuracy Assessment

- •

- Trueness: mean absolute surface deviation (μm) between test and reference meshes;

- •

- Precision: variability of trueness across 10 replicates (standard deviation).

2.8. Quality Control and Sample Size Rationale

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Accuracy Values

3.2. Statistical Analysis Results

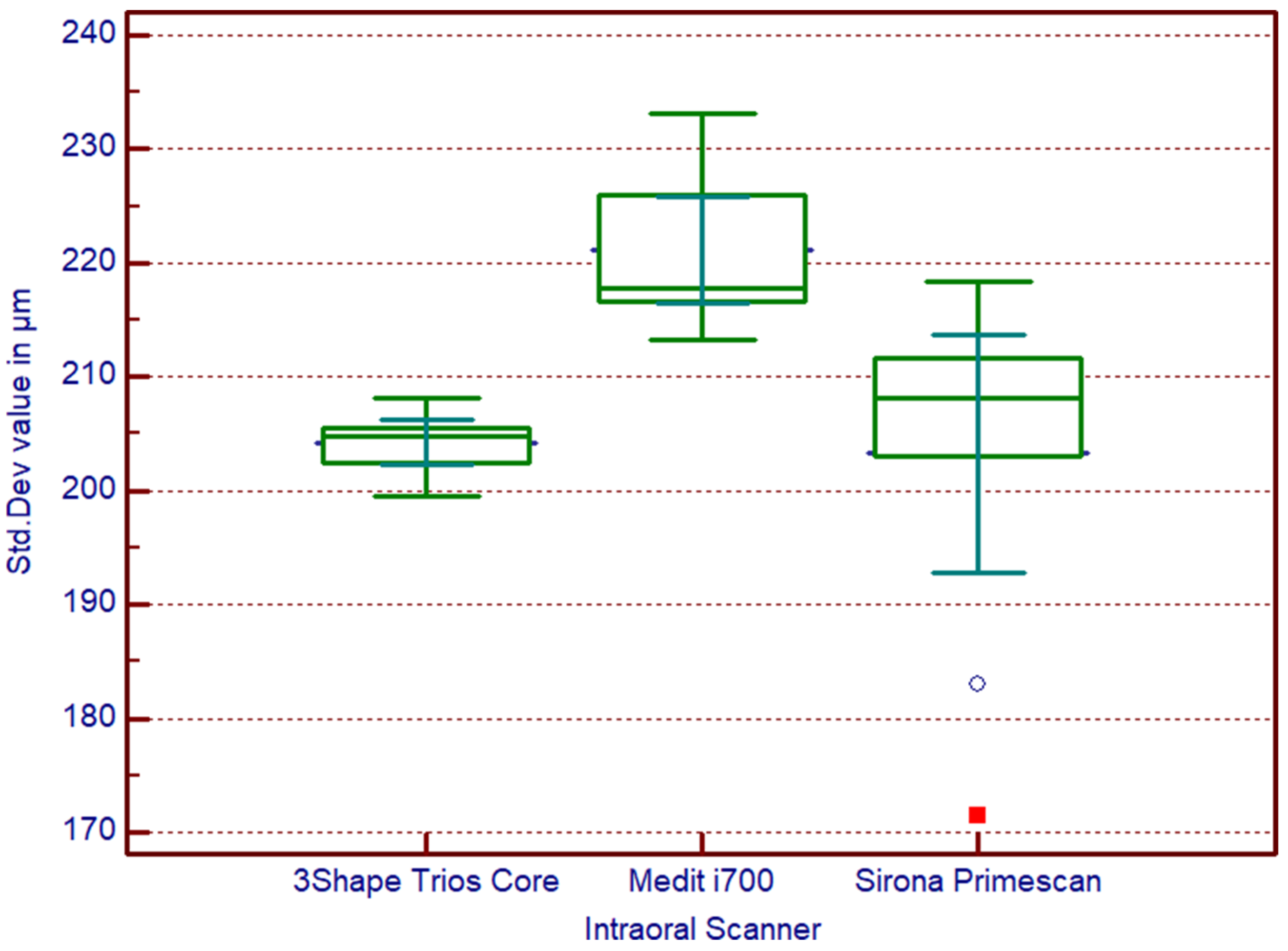

| Scanner | Mean (μm) | SD (μm) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medit i700 | 221.05 | 6.28 | 216.9–225.2 |

| Sirona Primescan | 202.76 | 13.89 | 193.1–212.4 |

| 3shape TRIOS Core | 204.21 | 2.61 | 202.4–206.0 |

| Statistic | df1 | df2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.990 | 2 | 27 | 0.014 |

3.3. Experimental Conclusions

- •

- Primescan offers the best trueness on average, but with higher variability between scans.

- •

- TRIOS Core provides comparable trueness while demonstrating the most consistent performance across repeated scans.

- •

- Medit i700, although falling within ranges considered clinically acceptable, showed significantly greater deviations, which could become critical in demanding full-arch, screw-retained protocols where passive fit is essential.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IOS | intraoral scanner |

| ROI | region of interest |

| ICP | iterative closest point |

| SD | standard deviation |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| HSD | honestly significant difference |

| CI | confidence interval |

References

- da Silva Salomão, G.V.; Chun, E.P.; Panegaci, R.D.S.; Santos, F.T. Analysis of Digital Workflow in Implantology. Case Rep. Dent. 2021, 2021, 6655908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tallarico, M. Computerization and Digital Workflow in Medicine: Focus on Digital Dentistry. Materials 2020, 13, 2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mangano, F.; Gandolfi, A.; Luongo, G.; Logozzo, S. Intraoral scanners in dentistry: A review of the current literature. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ludlow, M.; Renne, W. Digital Workflow in Implant Dentistry. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2017, 4, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, Z. Digital Dentistry: Past, Present, and Future. Digit. Med. Healthc. Technol. 2023, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.; Wang, X.; Tian, F.; Qu, Z.; Zhao, J. Comparison of accuracy between digital and conventional implant impressions: Two and three dimensional evaluations. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2022, 14, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lemos, C.A.; de Souza Batista, V.E.; Almeida, D.A.; Santiago Júnior, J.F.; Verri, F.R.; Pellizzer, E.P. Evaluation of cement-retained versus screw-retained implant-supported restorations for marginal bone loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadid, R.; Sadaqa, N. A comparison between screw- and cement-retained implant prostheses. A literature review. J. Oral Implantol. 2012, 38, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebel, K.S.; Gajjar, R.C. Cement-retained versus screw-retained implant restorations: Achieving optimal occlusion and esthetics in implant dentistry. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1997, 77, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misch, C.E. Dental Implant Prosthetics; Elsevier Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.; Okayasu, K.; Wang, H.L. Screw-versus cement-retained implant restorations: Current concepts. Implant Dent. 2010, 19, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parameshwari, G.; Chittaranjan, B.; Sudhir, N.; Anulekha-Avinash, C.K.; Taruna, M.; Ramureddy, M. Evaluation of accuracy of various impression techniques and impression materials in recording multiple implants placed unilaterally in a partially edentulous mandible—An in vitro study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2018, 10, e388–e395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pesce, P.; Nicolini, P.; Caponio, V.C.A.; Zecca, P.A.; Canullo, L.; Isola, G.; Baldi, D.; De Angelis, N.; Menini, M. Accuracy of Full-Arch Intraoral Scans Versus Conventional Impression: A Systematic Review with a Meta-Analysis and a Proposal to Standardise the Analysis of the Accuracy. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lyu, M.; Di, P.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, X. Accuracy of impressions for multiple implants: A comparative study of digital and conventional techniques. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schepke, U.; Meijer, H.J.; Kerdijk, W.; Cune, M.S. Digital versus analog complete-arch impressions for single-unit premolar implant crowns: Operating time and patient preference. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 403–406.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brintha Jei, J.; Anitha, K.V. Evolution of Impression Tray and Materials—A Literature Review. J. Clin. Prosthodont. Implantol. 2021, 3, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabor, A.; Zaharia, C.; Stan, A.; Gavrilovici, A.-M.; Negrutiu, M.-L.; Sinescu, C. Digital Dentistry—Digital Impression and CAD/CAM System Applications. J. Interdiscip. Med. 2017, 2, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, S.; Ribeiro, P.; Falcão, C.; Lemos, B.F.; Ríos-Carrasco, B.; Ríos-Santos, J.V.; Herrero-Climent, M. Digital Impressions in Implant Dentistry: A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- ISO 12836:2015; Dentistry—Accuracy (Trueness and Precision) of Digital Intra-Oral Scanners—Test Methods for Full Arch. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Imburgia, M.; Logozzo, S.; Hauschild, U.; Veronesi, G.; Mangano, C.; Mangano, F.G. Accuracy of four intraoral scanners in oral implantology: A comparative in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mangano, F.G.; Veronesi, G.; Hauschild, U.; Mijiritsky, E.; Mangano, C. Trueness and Precision of Four Intraoral Scanners in Oral Implantology: A Comparative in Vitro Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Richert, R.; Goujat, A.; Venet, L.; Viguie, G.; Viennot, S.; Robinson, P.; Farges, J.C.; Fages, M.; Ducret, M. Intraoral Scanner Technologies: A Review to Make a Successful Impression. J. Healthc. Eng. 2017, 2017, 8427595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nedelcu, R.G.; Persson, A.S. Scanning accuracy and precision in 4 intraoral scanners: An in vitro comparison based on 3-dimensional analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 112, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patzelt, S.B.; Vonau, S.; Stampf, S.; Att, W. Assessing the feasibility and accuracy of digitizing edentulous jaws. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2013, 144, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natsubori, R.; Fukazawa, S.; Chiba, T.; Tanabe, N.; Kihara, H.; Kondo, H. In vitro comparative analysis of scanning accuracy of intraoral and laboratory scanners in measuring the distance between multiple implants. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2022, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ferrini, F.; Mazzoleni, F.; Barbini, M.; Coppo, C.; Di Domenico, G.L.; Gherlone, E.F. Comparative Analysis of Intraoral Scanner Accuracy in a Six-Implant Complete-Arch Model: An In Vitro Study. Prosthesis 2024, 6, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkūnas, V.; Gečiauskaitė, A.; Jegelevičius, D.; Vaitiekūnas, M. Accuracy of digital implant impressions with intraoral scanners. A systematic review. Eur. J. Oral Implantol. 2017, 10, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van der Meer, W.J.; Andriessen, F.S.; Wismeijer, D.; Ren, Y. Application of intra-oral dental scanners in the digital workflow of implantology. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Michelinakis, G.; Apostolakis, D.; Kamposiora, P.; Papavasiliou, G.; Özcan, M. The direct digital workflow in fixed implant prosthodontics: A narrative review. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Papazoglou, E.; Wee, A.G.; Carr, A.B.; Urban, I.; Margaritis, V. Accuracy of complete-arch implant impression made with occlusal registration material. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 123, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renne, W.; Ludlow, M.; Fryml, J.; Schurch, Z.; Mennito, A.; Kessler, R.; Lauer, A. Evaluation of the accuracy of 7 digital scanners: An in vitro analysis based on 3-dimensional comparisons. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2017, 118, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patzelt, S.B.; Emmanouilidi, A.; Stampf, S.; Strub, J.R.; Att, W. Accuracy of full-arch scans using intraoral scanners. Clin. Oral Investig. 2014, 18, 1687–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güth, J.F.; Runkel, C.; Beuer, F.; Stimmelmayr, M.; Edelhoff, D.; Keul, C. Accuracy of five intraoral scanners compared to indirect digitalization. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 1445–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajaj, T.; Marian, D.; Zaharia, C.; Niculescu, S.T.; Negru, R.M.; Titihazan, F.; Rominu, M.; Sinescu, C.; Novac, A.C.; Dobrota, G.; et al. Fracture Resistance of CAD/CAM-Fabricated Zirconia and Lithium Disilicate Crowns with Different Margin Designs: Implications for Digital Dentistry. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajaj, T.; Lile, I.E.; Negru, R.M.; Niculescu, S.T.; Stuparu, S.; Rominu, M.; Sinescu, C.; Albu, P.; Titihazan, F.; Veja, I. Adhesive Performance of Zirconia and Lithium Disilicate Maryland Cantilever Restorations on Prepared and Non-Prepared Abutment Teeth: An In Vitro Comparative Study. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Source of Variation | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between groups | 2020.69 | 2 | 1010.34 | 11.393 | <0.001 |

| Within groups | 2394.49 | 27 | 88.68 | ||

| Total | 4415.17 | 29 |

| Scanner | Mean (μm) | Significant vs. |

|---|---|---|

| 3shape Trios Core | 204.21 | Medit i700 |

| Medit i700 | 221.05 | (Primescan, TRIOS Core) |

| Sirona Primescan | 202.76 | (Medit i700) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hajaj, T.; Veja, I.; Zaharia, C.; Lile, I.E.; Rominu, M.; Sinescu, C.; Titihazan, F.; Toman, E.-B.; Faur, A.B.; Constantin, G.D. Evaluation of Digital Imaging Accuracy Among Three Intraoral Scanners for Full-Arch Implant Rehabilitation. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010025

Hajaj T, Veja I, Zaharia C, Lile IE, Rominu M, Sinescu C, Titihazan F, Toman E-B, Faur AB, Constantin GD. Evaluation of Digital Imaging Accuracy Among Three Intraoral Scanners for Full-Arch Implant Rehabilitation. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleHajaj, Tareq, Ioana Veja, Cristian Zaharia, Ioana Elena Lile, Mihai Rominu, Cosmin Sinescu, Florina Titihazan, Evelyn-Beatrice Toman, Andrei Bogdan Faur, and George Dumitru Constantin. 2026. "Evaluation of Digital Imaging Accuracy Among Three Intraoral Scanners for Full-Arch Implant Rehabilitation" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010025

APA StyleHajaj, T., Veja, I., Zaharia, C., Lile, I. E., Rominu, M., Sinescu, C., Titihazan, F., Toman, E.-B., Faur, A. B., & Constantin, G. D. (2026). Evaluation of Digital Imaging Accuracy Among Three Intraoral Scanners for Full-Arch Implant Rehabilitation. Diagnostics, 16(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010025