ROMO1 as a Diagnostic Biomarker in Cervical Neoplasia: Evidence from Normal, Pre-Invasive, and Invasive Lesions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Patient Characteristics

- LSIL/CIN I: Dysplastic cells involving up to one-third of epithelial thickness.

- HSIL/CIN II/III: Dysplastic cells involving between one-third and two-thirds of the epithelium.

- FIGO staging: Classified according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2018 cervical cancer staging system.

- LVSI (lymphovascular space invasion): Presence of tumor cells within endothelial-lined lymphatic or vascular channels.

- N stage: N0 = no regional lymph node metastasis; N1 = regional nodal involvement.

2.2. Immunohistochemical Methods

Immunohistochemical Scores

H-Score

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Immunohistochemical Analysis

- I.

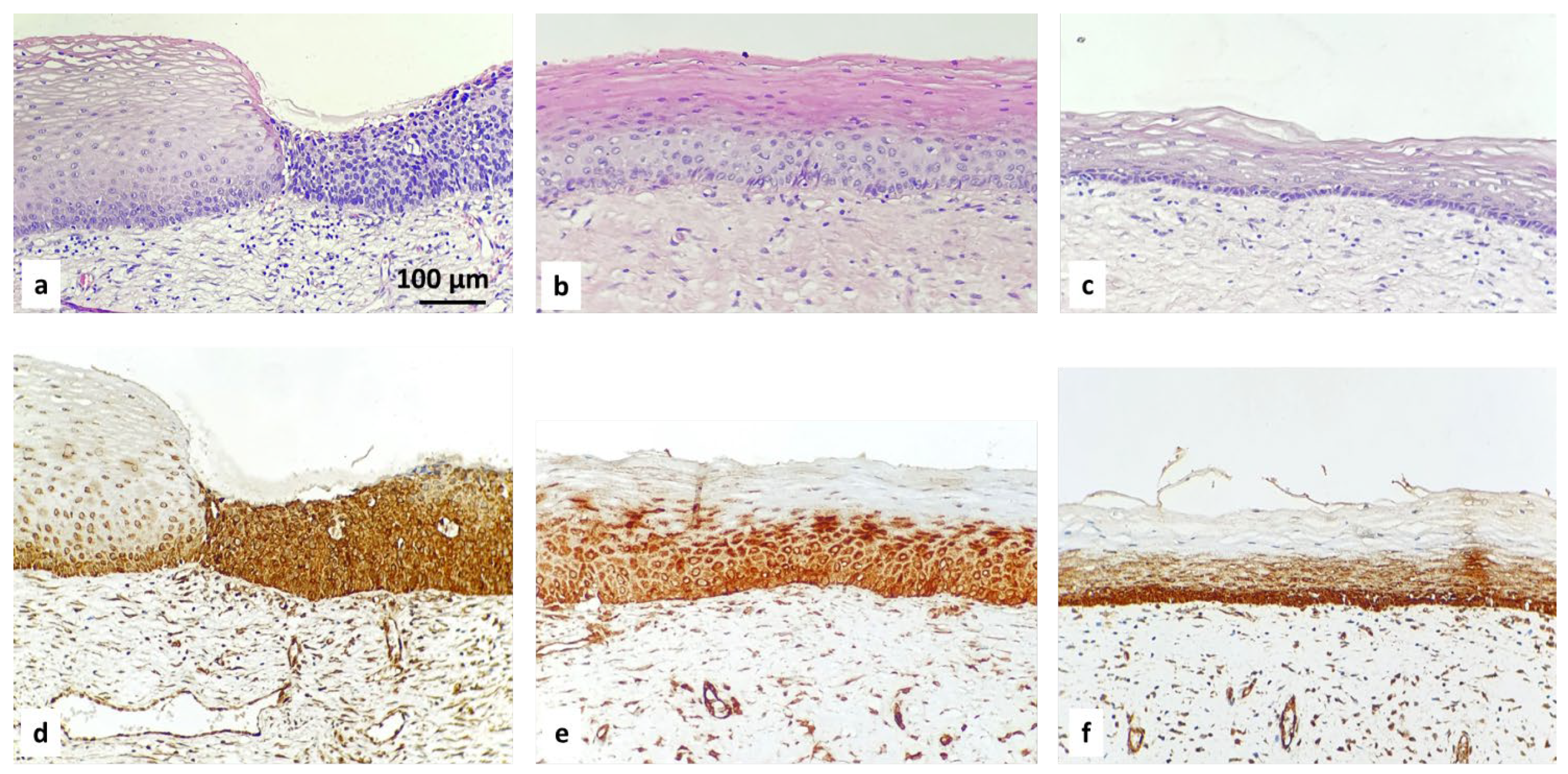

- ROMO1 in normal tissue from cervix

- -

- Positive basal expression with strong intensity in normal cervical epithelium.

- II.

- ROMO1 in squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL): LSIL, HSIL

- -

- Diffuse suprabasal expression with moderate to strong intensity in the area of abnormal cells in all CIN cases:

- LSIL/CIN 1: Refers to abnormal cells affecting about one-third of the thickness of the epithelium;

- HSIL/CIN 2: Refers to abnormal cells affecting about one-third to two-thirds of the epithelium;

- HSIL/CIN 3: Refers to abnormal cells affecting more than two-thirds of the epithelium.

3.2. ROMO1 Expression and Clinicopathologic Features in Invasive Carcinoma

- (1)

- FIGO stage I vs. II vs. III (χ2 p = 0.25)

- (2)

- Histologic grade G1 vs. G2 vs. G3 (χ2 p = 0.46)

- (3)

- Lymphovascular invasion (no vs. yes; χ2 p = 0.80)

- (4)

- Nodal status N0 vs. N1 (χ2 p = 0.67)

- (5)

- Patient age (≤50 y vs. >50 y; χ2 p = 0.38)

- (1)

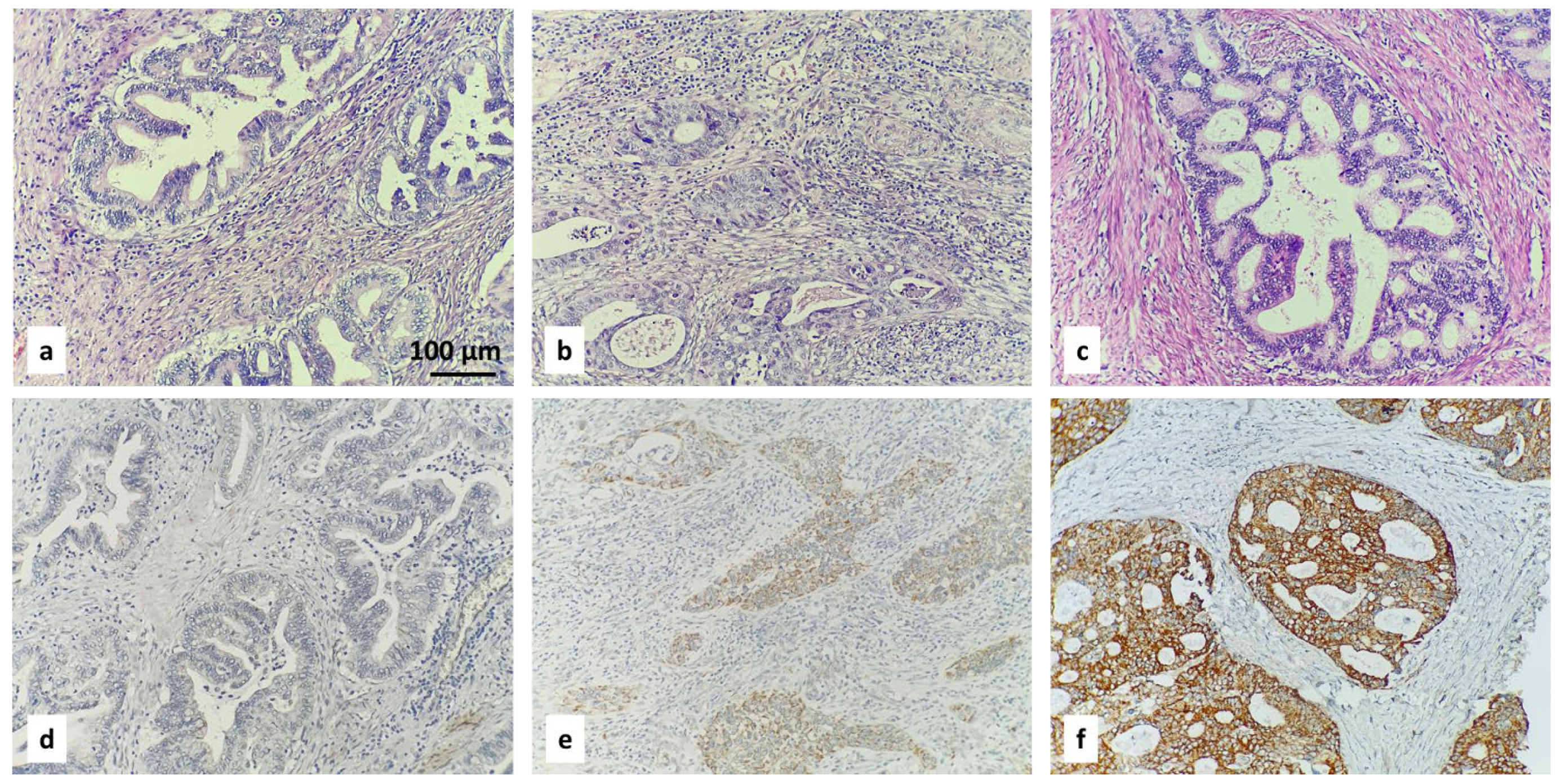

- ROMO1 expression differed significantly between histologic subtypes, with SCC showing higher expression than AC and ASC (p = 0.02). High ROMO1 immunoreactivity was most frequent in SCC, followed by ASC, and lowest in AC.

- (2)

- With regard to depth of invasion (pT stage) (pT1b1–pT2b; χ2 p = 0.035), we concluded that ROMO1 expression varied significantly across pT subcategories (pT1b1, pT1b2, pT1b3, pT2a, pT2b; χ2 p = 0.035). High H-score [2] was most frequent in pT1b2 (52%) and least in pT2a (11%), with intermediate levels in other groups (Figure 7).

4. Discussion

4.1. ROMO1 in CIN

4.2. ROMO1 in Invasive Cancer

4.3. Subtype Differences

4.4. Diagnostic Considerations

4.5. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Cervical Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Guida, F.; Kidman, R.; Ferlay, J.; Schüz, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Kithaka, B.; Ginsburg, O.; Mailhot Vega, R.B.; Galukande, M.; Parham, G.; et al. Global and regional estimates of orphans attributed to maternal cancer mortality in 2020. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2563–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/100-bulgaria-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Tomaziu-Todosia Anton, E.; Anton, G.I.; Scripcariu, I.S.; Dumitrașcu, I.; Scripcariu, D.V.; Balmus, I.M.; Ionescu, C.; Visternicu, M.; Socolov, D.G. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Antioxidant Strategies in Cervical Cancer—A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, C.; Ercoli, A.; Parisi, S.; Iatì, G.; Pergolizzi, S.; Alfano, L.; Pentimalli, F.; De Laurentiis, M.; Giordano, A.; Cortellino, S. Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Divergences in HPV-Positive Cervical vs. Oropharyngeal Cancers: A Critical Narrative Review. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J. The Cell-Cycle Arrest and Apoptotic Functions of p53 in Tumor Initiation and Progression. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a026104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouh, Y.T.; Kim, H.Y.; Yi, K.W.; Lee, N.W.; Kim, H.J.; Min, K.J. Enhancing Cervical Cancer Screening: Review of p16/Ki-67 Dual Staining as a Promising Triage Strategy. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaman, S.; Akidan, O.; Vatansever, M.; Misir, S.; Yaman, S.O. Analysis of ROMO1 Expression Levels and Its Oncogenic Role in Gastrointestinal Tract Cancers. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 14394–14407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoneva, E.; Dimitrova, P.D.; Metodiev, M.; Shivarov, V.; Vasileva-Slaveva, M.; Yordanov, A. The effects of ROMO1 on cervical cancer progression. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 248, 154561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoneva, E.; Yordanov, A. HPV Oncoproteins and Mitochondrial Reprogramming: The Central Role of ROMO1 in Oxidative Stress and Metabolic Shifts. Cells 2025, 14, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Jo, M.J.; Kim, B.R.; Kim, J.L.; Jeong, Y.A.; Na, Y.J.; Park, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, B.H.; et al. Overexpression of Romo1 is an unfavorable prognostic biomarker and a predictor of lymphatic metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Onco Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 4233–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Practice Bulletin No. 149: Endometrial cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 125, 1006–1026. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Healthy cervix | 30 | 100 |

| Precancerous lesion | 41 | 100 |

| LSIL | 6 | 14.6 |

| HSIL | 35 | 85.4 |

| Age | 205 | 100 |

| >50 | 106 | 51.7 |

| ≤50 | 99 | 48.3 |

| T stage | ||

| T1b1 | 68 | 33.17 |

| T1b2 | 82 | 40 |

| T1b3 | 26 | 12.6 |

| T2A | 20 | 9.75 |

| T2B | 9 | 4.39 |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 152 | 74.14 |

| N1 | 53 | 25.85 |

| FIGO stage | ||

| FIGO I | 138 | 67.3 |

| FIGO II | 14 | 6.82 |

| FIGO III | 53 | 25.85 |

| Histology | ||

| AC | 50 | 24.4 |

| ASC | 18 | 8.78 |

| SCC | 137 | 66.8 |

| Grade | ||

| G1 | 50 | 24.39 |

| G2 | 101 | 49.26 |

| G3 | 54 | 26.34 |

| LVSI | ||

| Yes | 47 | 22.92 |

| No | 158 | 77.1 |

| Total | 205 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tsoneva, E.; Damyanova, P.; Metodiev, M.V.; Shivarov, V.; Vasileva-Slaveva, M.; Gorcheva, Z.; Ivanova, Y.; Kornovski, Y.; Kostov, S.; Slavchev, S.; et al. ROMO1 as a Diagnostic Biomarker in Cervical Neoplasia: Evidence from Normal, Pre-Invasive, and Invasive Lesions. Diagnostics 2026, 16, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010024

Tsoneva E, Damyanova P, Metodiev MV, Shivarov V, Vasileva-Slaveva M, Gorcheva Z, Ivanova Y, Kornovski Y, Kostov S, Slavchev S, et al. ROMO1 as a Diagnostic Biomarker in Cervical Neoplasia: Evidence from Normal, Pre-Invasive, and Invasive Lesions. Diagnostics. 2026; 16(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsoneva, Eva, Polina Damyanova, Metodi V. Metodiev, Velizar Shivarov, Mariela Vasileva-Slaveva, Zornitsa Gorcheva, Yonka Ivanova, Yavor Kornovski, Stoyan Kostov, Stanislav Slavchev, and et al. 2026. "ROMO1 as a Diagnostic Biomarker in Cervical Neoplasia: Evidence from Normal, Pre-Invasive, and Invasive Lesions" Diagnostics 16, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010024

APA StyleTsoneva, E., Damyanova, P., Metodiev, M. V., Shivarov, V., Vasileva-Slaveva, M., Gorcheva, Z., Ivanova, Y., Kornovski, Y., Kostov, S., Slavchev, S., Nikolova, M., Yordanov, A., & Watrowski, R. (2026). ROMO1 as a Diagnostic Biomarker in Cervical Neoplasia: Evidence from Normal, Pre-Invasive, and Invasive Lesions. Diagnostics, 16(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics16010024