Metabolomics of Prostate Cancer and Clinical Profiles Following Radiotherapy: Need for a Precision Phylometabolomics Approach †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mass Spectrometry-Based Global (Untargeted) Metabolomics

2.2. Phylogenetic Modeling of MS Data: MS-Based Phylometabolomics

2.3. Data Collection and Metabolic Pathway Analysis

3. Results

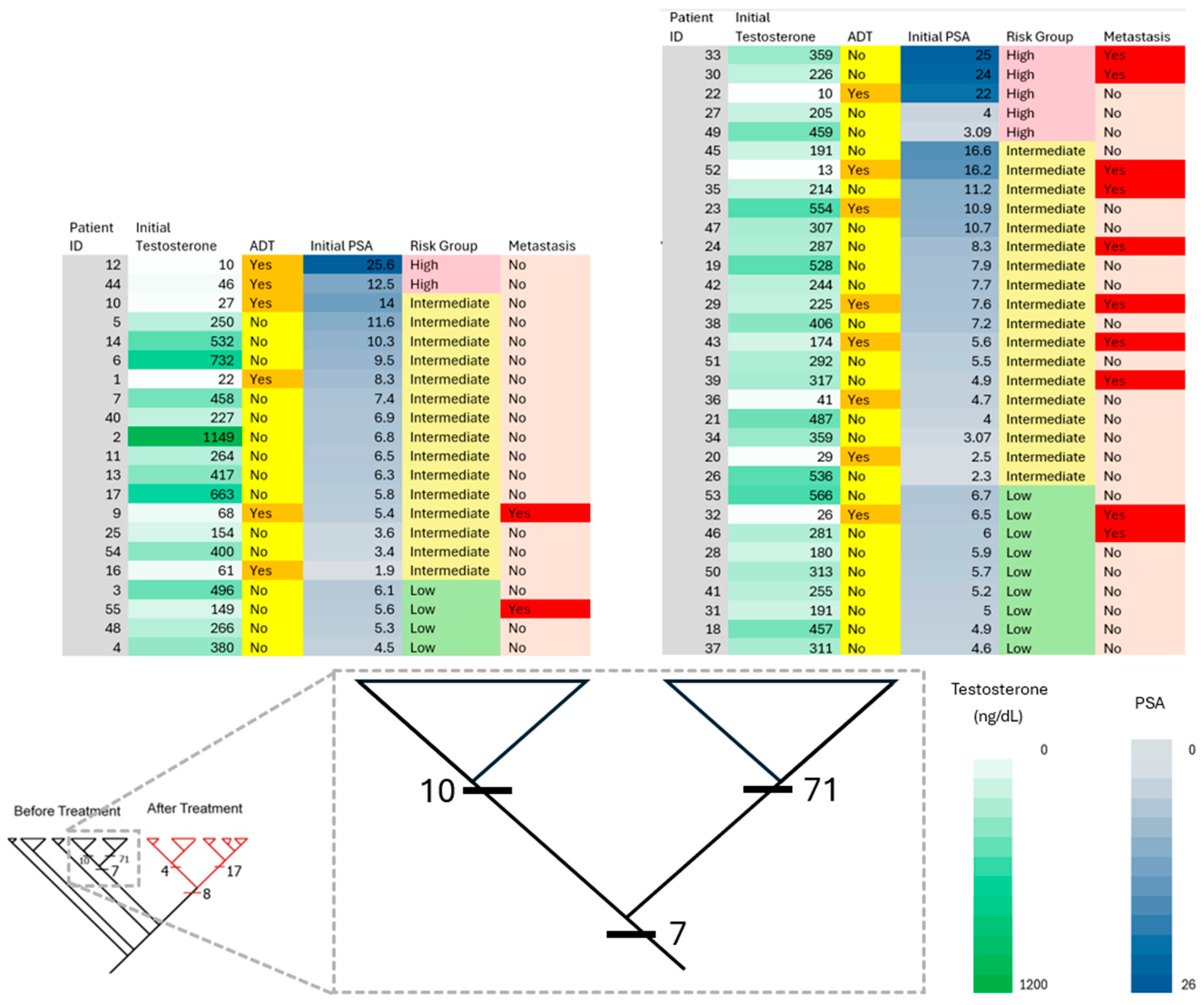

3.1. Patient Characteristics and Treatment Planning

3.2. Distribution of Putatively Identified Compounds Before RT

3.3. Distribution of Putatively Identified Compounds After RT

4. Discussion

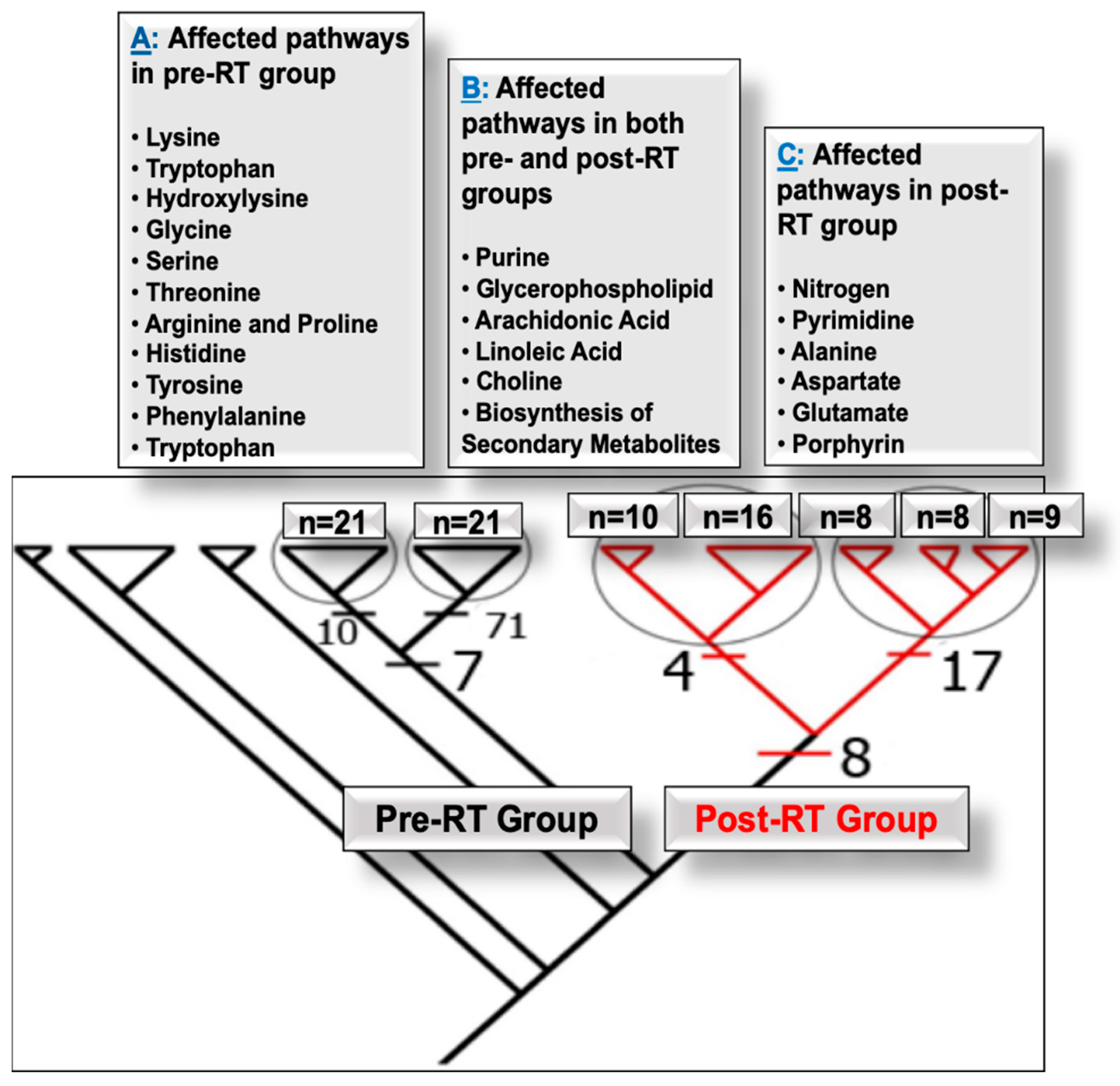

4.1. Pathways Altered in PCa Patients Pre- and Post-RT

4.1.1. Pre-RT Alterations

4.1.2. Pre- and Post-RT Alterations

4.1.3. Post-RT Alterations

4.2. Compounds Associated with PCa Progression and Metastasis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADT | Androgen deprivation therapy |

| PCa | Prostate cancer |

| PE | Phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PC | Phosphatidylcholine |

| RT | Radiotherapy (radiation treatment) |

| SBRT | Stereotactic body radiation therapy |

References

- Jemal, A.; Bray, F.; Center, M.M.; Ferlay, J.; Ward, E.; Forman, D. Global Cancer Statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: Sources, Methods and Major Patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawla, P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, E.J.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Soerjomataram, I.; Briganti, A.; Dahut, W.; Bray, F.; Jemal, A. Recent Patterns and Trends in Global Prostate Cancer Incidence and Mortality: An Update. Eur. Urol. 2025, 87, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medipally, D.K.R.; Nguyen, T.N.Q.; Bryant, J.; Untereiner, V.; Sockalingum, G.D.; Cullen, D.; Noone, E.; Bradshaw, S.; Finn, M.; Dunne, M.; et al. Monitoring Radiotherapeutic Response in Prostate Cancer Patients Using High Throughput FTIR Spectroscopy of Liquid Biopsies. Cancers 2019, 11, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolla, M.; Gonzalez, D.; Warde, P.; Dubois, J.B.; Mirimanoff, R.O.; Storme, G.; Bernier, J.; Kuten, A.; Sternberg, C.; Gil, T.; et al. Improved Survival in Patients with Locally Advanced Prostate Cancer Treated with Radiotherapy and Goserelin. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.U.; Hunt, D.; McGowan, D.G.; Amin, M.B.; Chetner, M.P.; Bruner, D.W.; Leibenhaut, M.H.; Husain, S.M.; Rotman, M.; Souhami, L.; et al. Radiotherapy and Short-Term Androgen Deprivation for Localized Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shipley, W.U.; Seiferheld, W.; Lukka, H.R.; Major, P.P.; Heney, N.M.; Grignon, D.J.; Sartor, O.; Patel, M.P.; Bahary, J.-P.; Zietman, A.L.; et al. Radiation with or without Antiandrogen Therapy in Recurrent Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.D.; Heidenreich, A.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Tombal, B.; Pompeo, A.C.L.; Mendoza-Valdes, A.; Miller, K.; Debruyne, F.M.J.; Klotz, L. Androgen-Targeted Therapy in Men with Prostate Cancer: Evolving Practice and Future Considerations. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2019, 22, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarish, F.L.; Schultz, N.; Tanoglidi, A.; Hamberg, H.; Letocha, H.; Karaszi, K.; Hamdy, F.C.; Granfors, T.; Helleday, T. Castration Radiosensitizes Prostate Cancer Tissue by Impairing DNA Double-Strand Break Repair. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 312re11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, C.; Musiani, P.; Pompa, P.; Cipollone, G.; Di Carlo, E. Androgen Deprivation Boosts Prostatic Infiltration of Cytotoxic and Regulatory T Lymphocytes and Has No Effect on Disease-Free Survival in Prostate Cancer Patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escamilla, J.; Schokrpur, S.; Liu, C.; Priceman, S.J.; Moughon, D.; Jiang, Z.; Pouliot, F.; Magyar, C.; Sung, J.L.; Xu, J.; et al. CSF1 Receptor Targeting in Prostate Cancer Reverses Macrophage-Mediated Resistance to Androgen Blockade Therapy. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsueh, J.Y.; Gallagher, L.; Koh, M.J.; Shah, S.; Danner, M.; Zwart, A.; Ayoob, M.; Kumar, D.; Leger, P.; Dawson, N.A.; et al. The Impact of Neoadjuvant Relugolix on Multi-Dimensional Patient-Reported Fatigue. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1412786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I.M.; Pauler, D.K.; Goodman, P.J.; Tangen, C.M.; Lucia, M.S.; Parnes, H.L.; Minasian, L.M.; Ford, L.G.; Lippman, S.M.; Crawford, E.D.; et al. Prevalence of Prostate Cancer among Men with a Prostate-Specific Antigen Level < or =4.0 Ng per Milliliter. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S. PSA and beyond: Alternative Prostate Cancer Biomarkers. Cell. Oncol. 2016, 39, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giskeødegård, G.F.; Madssen, T.S.; Euceda, L.R.; Tessem, M.-B.; Moestue, S.A.; Bathen, T.F. NMR-based metabolomics of biofluids in cancer. NMR Biomed. 2019, 32, e3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, P.F. New Evidence for the Benefit of Prostate-Specific Antigen Screening: Data From 400,887 Kaiser Permanente Patients. Urology 2018, 118, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutrone, R.; Lowentritt, B.; Neuman, B.; Donovan, M.J.; Hallmark, E.; Cole, T.J.; Yao, Y.; Biesecker, C.; Kumar, S.; Verma, V.; et al. ExoDx Prostate Test as a Predictor of Outcomes of High-Grade Prostate Cancer—An Interim Analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2023, 26, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, W.C.H.; de Jong, H.; Steyaert, S.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Mulders, P.F.A.; Schalken, J.A. Clinical Use of the mRNA Urinary Biomarker SelectMDx Test for Prostate Cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022, 25, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michigan Center for Translational Pathology. Available online: https://mlabs.umich.edu/tests/myprostatescoretm-mps (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Becerra, M.F.; Bhat, A.; Mouzannar, A.; Atluri, V.S.; Punnen, S. Serum and Urinary Biomarkers for Detection and Active Surveillance of Prostate Cancer. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2019, 29, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Pan, Q.; Zhao, B. Liquid Biopsy Techniques and Pancreatic Cancer: Diagnosis, Monitoring, and Evaluation. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, P.; Briganti, A.; Bossi, A. Re: Christopher J.D. Wallis, Refik Saskin, Richard Choo; et al. Surgery Versus Radiotherapy for Clinically-Localized Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur Urol 2016;70:21–30. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, e15–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhov, P.G.; Dashtiev, M.I.; Bondartsov, L.V.; Lisitsa, A.V.; Moshkovskiĭ, S.A.; Archakov, A.I. Metabolic fingerprinting of blood plasma for patients with prostate cancer. Biomed. Khim. 2009, 55, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trock, B.J. Application of Metabolomics to Prostate Cancer. Urol. Oncol. 2011, 29, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, K.S.; Petersen, D.R. Exploring the Biology of Lipid Peroxidation Derived Protein Carbonylation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011, 24, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, M.; Warde, P.; Ménard, C.; Chung, P.; Toi, A.; Ishkanian, A.; McLean, M.; Pintilie, M.; Sykes, J.; Gospodarowicz, M.; et al. Tumor Hypoxia Predicts Biochemical Failure Following Radiotherapy for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 2108–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moren, X.; Lhomme, M.; Bulla, A.; Sanchez, J.-C.; Kontush, A.; James, R.W. Proteomic and Lipidomic Analyses of Paraoxonase Defined High Density Lipoprotein Particles: Association of Paraoxonase with the Anti-Coagulant, Protein S. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2016, 10, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, W.A.; Lawton, C.A.; Jani, A.B.; Pollack, A.; Feng, F.Y. Biomarkers of Outcome in Patients with Localized Prostate Cancer Treated With Radiotherapy. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 27, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keam, S.P.; Caramia, F.; Gamell, C.; Paul, P.J.; Arnau, G.M.; Neeson, P.J.; Williams, S.G.; Haupt, Y. The Transcriptional Landscape of Radiation-Treated Human Prostate Cancer: Analysis of a Prospective Tissue Cohort. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2018, 100, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Pan, D.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Yan, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Yang, M.; Liu, G. Applications of Multi-omics Analysis in Human Diseases. MedComm 2023, 4, e315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, G.A.N.; Zhang, S.; Gu, H.; Asiago, V.; Shanaiah, N.; Raftery, D. Metabolomics-Based Methods for Early Disease Diagnostics. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2008, 8, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Heiden, M.G. Targeting Cancer Metabolism: A Therapeutic Window Opens. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011, 10, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Li, K.; Zhang, X. Next-Generation Metabolomics in Lung Cancer Diagnosis, Treatment and Precision Medicine: Mini Review. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 115774–115786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J.; Amri, H.; Noursi, D.; Abu-Asab, M. Computational Tools for Parsimony Phylogenetic Analysis of Omics Data. OMICS 2015, 19, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarelli, J.A.; Ware, K.E.; Kostadinov, R.; Robinson, J.M.; Amri, H.; Abu-Asab, M.; Fourie, N.; Diogo, R.; Swofford, D.; Townsend, J.P. PhyloOncology: Understanding Cancer through Phylogenetic Analysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2017, 1867, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbantoglu, S.; Abu-Asab, M.; Suy, S.; Collins, S.; Amri, H. Metabolomics-Based Biosignatures of Prostate Cancer in Patients Following Radiotherapy. OMICS 2019, 23, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Asab, M.S.; Chaouchi, M.; Amri, H. Phylogenetic Modeling of Heterogeneous Gene-Expression Microarray Data from Cancerous Specimens. OMICS 2008, 12, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalbantoglu, S.; Abu-Asab, M.; Tan, M.; Zhang, X.; Cai, L.; Amri, H. Study of Clinical Survival and Gene Expression in a Sample of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma by Parsimony Phylogenetic Analysis. OMICS 2016, 20, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzone, G.; Manzini, R.; Noci, G. Evolutionary Trends in Environmental Reporting. Bus. Strategy Environ. 1996, 5, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phylogenetic Classification. In Phylogenetics; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 229–259. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.F.; Varghese, R.S.; Zhou, B.; Nezami Ranjbar, M.R.; Zhao, Y.; Tsai, T.-H.; Di Poto, C.; Wang, J.; Goerlitz, D.; Luo, Y.; et al. LC–MS Based Serum Metabolomics for Identification of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Biomarkers in Egyptian Cohort. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 5914–5923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Want, E.J.; O’Maille, G.; Abagyan, R.; Siuzdak, G. XCMS: Processing Mass Spectrometry Data for Metabolite Profiling Using Nonlinear Peak Alignment, Matching, and Identification. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Asab, M.; Chaouchi, M.; Amri, H. Phyloproteomics: What Phylogenetic Analysis Reveals about Serum Proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 2006, 5, 2236–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Felsenstein, J. PHYLIP-Phylogeny Inference Package (Version 3.2). Cladistics 1989, 5, 164–166. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Page, R.D. TreeView: An Application to Display Phylogenetic Trees on Personal Computers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1996, 12, 357–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Jewison, T.; Guo, A.C.; Wilson, M.; Knox, C.; Liu, Y.; Djoumbou, Y.; Mandal, R.; Aziat, F.; Dong, E.; et al. HMDB 3.0—The Human Metabolome Database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D801–D807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Lewis, I.A.; Hegeman, A.D.; Anderson, M.E.; Li, J.; Schulte, C.F.; Westler, W.M.; Eghbalnia, H.R.; Sussman, M.R.; Markley, J.L. Metabolite Identification via the Madison Metabolomics Consortium Database. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tautenhahn, R.; Cho, K.; Uritboonthai, W.; Zhu, Z.; Patti, G.J.; Siuzdak, G. An Accelerated Workflow for Untargeted Metabolomics Using the METLIN Database. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 826–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sud, M.; Fahy, E.; Cotter, D.; Brown, A.; Dennis, E.A.; Glass, C.K.; Merrill, A.H.; Murphy, R.C.; Raetz, C.R.H.; Russell, D.W.; et al. LMSD: LIPID MAPS Structure Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, D527–D532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. KEGG: New Perspectives on Genomes, Pathways, Diseases and Drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D353–D361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamburov, A.; Stelzl, U.; Lehrach, H.; Herwig, R. The ConsensusPathDB Interaction Database: 2013 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D793–D800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paydar, I.; Cyr, R.A.; Yung, T.M.; Lei, S.; Collins, B.T.; Chen, L.N.; Suy, S.; Dritschilo, A.; Lynch, J.H.; Collins, S.P. Proctitis 1 Week after Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer: Implications for Clinical Trial Design. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, M.; Hung, M.-Y.; Yung, T.M.; Ayoob, M.; Lei, S.; Collins, B.T.; Suy, S.; Collins, S.P. Utilization of Patient-Reported Outcomes to Guide Symptom Management during Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercado, C.; Kress, M.-A.; Cyr, R.A.; Chen, L.N.; Yung, T.M.; Bullock, E.G.; Lei, S.; Collins, B.T.; Satinsky, A.N.; Harter, K.W.; et al. Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy with Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy Boost for Unfavorable Prostate Cancer: The Georgetown University Experience. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, A.V.; Whittington, R.; Malkowicz, S.B.; Schultz, D.; Blank, K.; Broderick, G.A.; Tomaszewski, J.E.; Renshaw, A.A.; Kaplan, I.; Beard, C.J.; et al. Biochemical Outcome after Radical Prostatectomy, External Beam Radiation Therapy, or Interstitial Radiation Therapy for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer. JAMA 1998, 280, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edison, A.S.; Hall, R.D.; Junot, C.; Karp, P.D.; Kurland, I.J.; Mistrik, R.; Reed, L.K.; Saito, K.; Salek, R.M.; Steinbeck, C.; et al. The Time Is Right to Focus on Model Organism Metabolomes. Metabolites 2016, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Yim, S.H.; Lee, S.-G.; Kim, E.B.; Lee, S.-R.; Chang, K.-T.; Buffenstein, R.; Lewis, K.N.; Park, T.J.; Miller, R.A.; et al. Organization of the Mammalian Metabolome According to Organ Function, Lineage Specialization, and Longevity. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeb, K.R.; Loeb, L.A. Significance of Multiple Mutations in Cancer. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, D.C. The Genetic Basis of Colorectal Cancer: Insights into Critical Pathways of Tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology 2000, 119, 854–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Yamashita, J.; Watanabe, T. Molecular Genetic Analysis of Deep-Seated Glioblastomas. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2004, 153, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adsay, N.V.; Merati, K.; Andea, A.; Sarkar, F.; Hruban, R.H.; Wilentz, R.E.; Goggins, M.; Iocobuzio-Donahue, C.; Longnecker, D.S.; Klimstra, D.S. The Dichotomy in the Preinvasive Neoplasia to Invasive Carcinoma Sequence in the Pancreas: Differential Expression of MUC1 and MUC2 Supports the Existence of Two Separate Pathways of Carcinogenesis. Mod. Pathol. 2002, 15, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petricoin, E.E.; Paweletz, C.P.; Liotta, L.A. Clinical Applications of Proteomics: Proteomic Pattern Diagnostics. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2002, 7, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexe, G.; Alexe, S.; Liotta, L.A.; Petricoin, E.; Reiss, M.; Hammer, P.L. Ovarian Cancer Detection by Logical Analysis of Proteomic Data. Proteomics 2004, 4, 766–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrads, T.P.; Fusaro, V.A.; Ross, S.; Johann, D.; Rajapakse, V.; Hitt, B.A.; Steinberg, S.M.; Kohn, E.C.; Fishman, D.A.; Whitely, G.; et al. High-Resolution Serum Proteomic Features for Ovarian Cancer Detection. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2004, 11, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Rao, M.; Glimm, J.; Kovach, J.S. Detection of Cancer-Specific Markers amid Massive Mass Spectral Data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 14666–14671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, B.-L.; Qu, Y.; Davis, J.W.; Ward, M.D.; Clements, M.A.; Cazares, L.H.; Semmes, O.J.; Schellhammer, P.F.; Yasui, Y.; Feng, Z.; et al. Serum Protein Fingerprinting Coupled with a Pattern-Matching Algorithm Distinguishes Prostate Cancer from Benign Prostate Hyperplasia and Healthy Men. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 3609–3614. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.S.H.; Lin, X.; Chua, K.L.M.; Lam, P.Y.; Soo, K.-C.; Chua, M.L.K. Exploiting Molecular Genomics in Precision Radiation Oncology: A Marriage of Biological and Physical Precision. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 6 (Suppl. 2), S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiakis, E.C.; Mak, T.D.; Anizan, S.; Amundson, S.A.; Barker, C.A.; Wolden, S.L.; Brenner, D.J.; Fornace, A.J. Development of a Metabolomic Radiation Signature in Urine from Patients Undergoing Total Body Irradiation. Radiat. Res. 2014, 181, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacombe, J.; Mange, A.; Azria, D.; Solassol, J. Identification of predictive biomarkers to radiotherapy outcome through proteomics approaches. Cancer Radiother. 2013, 17, 62–69; quiz 70, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J.; Jeyaseelan, A.K.; Ybarra, N.; David, M.; Faria, S.; Souhami, L.; Cury, F.; Duclos, M.; El Naqa, I. Contrasting Analytical and Data-Driven Frameworks for Radiogenomic Modeling of Normal Tissue Toxicities in Prostate Cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2015, 115, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, E.; Evans, K.R.; Ménard, C.; Pintilie, M.; Bristow, R.G. Practical Approaches to Proteomic Biomarkers within Prostate Cancer Radiotherapy Trials. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008, 27, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Asab, M.; Zhang, M.; Amini, D.; Abu-Asab, N.; Amri, H. Endometriosis Gene Expression Heterogeneity and Biosignature: A Phylogenetic Analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2011, 2011, 719059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Asab, M.; Chaouchi, M.; Amri, H. Evolutionary Medicine: A Meaningful Connection between Omics, Disease, and Treatment. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2008, 2, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarnat, H.B.; Netsky, M.G. Hypothesis: Phylogenetic Diseases of the Nervous System. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 1984, 11, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Putluri, N.; Shojaie, A.; Vasu, V.T.; Nalluri, S.; Vareed, S.K.; Putluri, V.; Vivekanandan-Giri, A.; Byun, J.; Pennathur, S.; Sana, T.R.; et al. Metabolomic Profiling Reveals a Role for Androgen in Activating Amino Acid Metabolism and Methylation in Prostate Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreekumar, A.; Poisson, L.M.; Rajendiran, T.M.; Khan, A.P.; Cao, Q.; Yu, J.; Laxman, B.; Mehra, R.; Lonigro, R.J.; Li, Y.; et al. Metabolomic Profiles Delineate Potential Role for Sarcosine in Prostate Cancer Progression. Nature 2009, 457, 910–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, T.; Vares, G.; Wang, B.; Nenoi, M. Chronic Intake of Japanese Sake Mediates Radiation-Induced Metabolic Alterations in Mouse Liver. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ren, W.; Huang, X.; Deng, J.; Li, T.; Yin, Y. Potential Mechanisms Connecting Purine Metabolism and Cancer Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannkuk, E.L.; Laiakis, E.C.; Mak, T.D.; Astarita, G.; Authier, S.; Wong, K.; Fornace, A.J. A Lipidomic and Metabolomic Serum Signature from Nonhuman Primates Exposed to Ionizing Radiation. Metabolomics 2016, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wu, L.; Xu, L. Mendelian Randomization Analysis Reveals Potential Causal Relationships between Serum Lipid Metabolites and Prostate Cancer Risk. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelonek, K.; Pietrowska, M.; Ros, M.; Zagdanski, A.; Suchwalko, A.; Polanska, J.; Marczyk, M.; Rutkowski, T.; Skladowski, K.; Clench, M.R.; et al. Radiation-Induced Changes in Serum Lipidome of Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 6609–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurmi, K.; Haigis, M.C. Nitrogen Metabolism in Cancer and Immunity. Trends Cell Biol. 2020, 30, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, M.; Oshikawa, K.; Shimizu, H.; Yoshioka, S.; Takahashi, M.; Izumi, Y.; Bamba, T.; Tateishi, C.; Tomonaga, T.; Matsumoto, M.; et al. A Shift in Glutamine Nitrogen Metabolism Contributes to the Malignant Progression of Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, D.; Bragazzi Cunha, J.; Elenbaas, J.S.; Bonkovsky, H.L.; Shavit, J.A.; Omary, M.B. Porphyrin-Induced Protein Oxidation and Aggregation as a Mechanism of Porphyria-Associated Cell Injury. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 8, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Bo, S.; Zeng, K.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Chen, S.; Jiang, Z.-X. Fluorinated Porphyrin-Based Theranostics for Dual Imaging and Chemo-Photodynamic Therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 4469–4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, M.-K.; Oberley-Deegan, R.E.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Talmon, G.A.; Somarelli, J.A.; Xu, S.; Kosmacek, E.A.; Griess, B.; Mir, S.; Shrishrimal, S.; et al. Manganese Porphyrin and Radiotherapy Improves Local Tumor Response and Overall Survival in Orthotopic Murine Mammary Carcinoma Models. Radiat. Res. 2021, 195, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Tomek, P. Tryptophan: A Rheostat of Cancer Immune Escape Mediated by Immunosuppressive Enzymes IDO1 and TDO. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 636081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Chiesa, M.; Carlomagno, S.; Frumento, G.; Balsamo, M.; Cantoni, C.; Conte, R.; Moretta, L.; Moretta, A.; Vitale, M. The Tryptophan Catabolite L-Kynurenine Inhibits the Surface Expression of NKp46- and NKG2D-Activating Receptors and Regulates NK-Cell Function. Blood 2006, 108, 4118–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rad Pour, S.; Morikawa, H.; Kiani, N.A.; Yang, M.; Azimi, A.; Shafi, G.; Shang, M.; Baumgartner, R.; Ketelhuth, D.F.J.; Kamleh, M.A.; et al. Exhaustion of CD4+ T-Cells Mediated by the Kynurenine Pathway in Melanoma. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezrich, J.D.; Fechner, J.H.; Zhang, X.; Johnson, B.P.; Burlingham, W.J.; Bradfield, C.A. An Interaction between Kynurenine and the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Can Generate Regulatory T Cells. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 3190–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liang, X.; Dong, W.; Fang, Y.; Lv, J.; Zhang, T.; Fiskesund, R.; Xie, J.; Liu, J.; Yin, X.; et al. Tumor-Repopulating Cells Induce PD-1 Expression in CD8+ T Cells by Transferring Kynurenine and AhR Activation. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 480–494.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, Z.; Fu, Z.; Wang, Y. Development and Validation of Tryptophan Metabolism-Related Risk Model and Molecular Subtypes for Predicting Postoperative Biochemical Recurrence in Prostate Cancer. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2025, 14, 1082–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoguchi, T.; Nohara, Y.; Nojiri, C.; Nakashima, N. Association of Serum Bilirubin Levels with Risk of Cancer Development and Total Death. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glunde, K.; Bhujwalla, Z.M.; Ronen, S.M. Choline Metabolism in Malignant Transformation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 835–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giskeødegård, G.F.; Hansen, A.F.; Bertilsson, H.; Gonzalez, S.V.; Kristiansen, K.A.; Bruheim, P.; Mjøs, S.A.; Angelsen, A.; Bathen, T.F.; Tessem, M.-B. Metabolic Markers in Blood Can Separate Prostate Cancer from Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113, 1712–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.C.; Kong, S.-Y.; Jang, S.-G.; Kim, K.-H.; Ahn, S.-A.; Park, W.-S.; Park, S.; Yun, T.; Eom, H.-S. Identification of Hypoxanthine as a Urine Marker for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma by Low-Mass-Ion Profiling. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Sanchez-Espiridion, B.; Lin, M.; White, L.; Mishra, L.; Raju, G.S.; Kopetz, S.; Eng, C.; Hildebrandt, M.A.T.; Chang, D.W.; et al. Global and Targeted Serum Metabolic Profiling of Colorectal Cancer Progression. Cancer 2017, 123, 4066–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, P.; Bizzarri, F.P.; Filomena, G.B.; Marino, F.; Iacovelli, R.; Ciccarese, C.; Boccuto, L.; Ragonese, M.; Gavi, F.; Rossi, F.; et al. Relationship Between Loss of Y Chromosome and Urologic Cancers: New Future Perspectives. Cancers 2024, 16, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No of Patients (N = 55) | (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age | Median 68 (52–90) | ||

| Race | Black | 15 | 27.2 |

| White | 37 | 67.2 | |

| Other | 3 | 5.6 | |

| Clinical and Pathological Characteristics | |||

| Pretreatment PSA (ng/mL) | Median 8.1 (1.9–25.6) | ||

| T-stage | T1c | 40 | 72.7 |

| T2a-b | 12 | 21.8 | |

| T2c | 3 | 5.5 | |

| Gleason Score | 6 (3 + 3) | 20 | 36.3 |

| 7(3 + 4; 4 + 3) | 30 | 54.5 | |

| 8(3 + 5; 4 + 4) | 4 | 7.2 | |

| 9(4 + 5; 5 + 4) | 1 | 2 | |

| D’Amico classification | |||

| Risk Group (D’Amico classification) | Low | 14 | 25.4 |

| Intermediate | 34 | 61.8 | |

| High | 7 | 12.8 | |

| Treatment Plan | |||

| ADT | Yes | 13 | 23.6 |

| No | 42 | 76.4 | |

| Treatment: SBRT (CK) only | Fraction 5; Dose (Gy) 35 | 6 | 10.9 |

| Fraction 5; Dose (Gy) 36.25 | 36 | 65.4 | |

| Treatment: SBRT/IMRT combination | Fraction 3/25; Dose (Gy) 19.5/45 | 9 | 16.3 |

| Fraction 3/28; Dose (Gy) 19.5/50.4 | 4 | 7.2 | |

| Risk Assessment | Nº of Patients | Treatment Protocol | Precision Biosignatures |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | 7 | Pre-RT | Hypoxanthine m/z 159.0093618 m/z 120.0038 m/z 380.772 m/z 197.08 |

| Post-RT | Phthalic acid 5′-Benzoylphosphoadenosine Bilirubin Phosphatidylethanolamine Phosphatidylcholine m/z 416.91035669 m/z 632.2994 m/z 312.0288 m/z 262.2532 m/z 184.0735 m/z 723.5443 m/z 701.561 | ||

| Metastatic [2 high risk; 6 intermediate; 3 low risk] | 11 | Pre-RT | D-Tryptophan Hypoxanthine Tetrahydroisoquinoline Dihydrosanguinarine Methylglutaric acid |

| Post-RT | Carbamic acid Phosphoric acid Bilirubin Phthalic acid 5′-Benzoylphosphoadenosine. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amri, H.; Sturgeon, C.; Posawatz, D.; Abu-Asab, M.; Collins, R.R.; Suy, S.; Collins, S.P. Metabolomics of Prostate Cancer and Clinical Profiles Following Radiotherapy: Need for a Precision Phylometabolomics Approach. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243242

Amri H, Sturgeon C, Posawatz D, Abu-Asab M, Collins RR, Suy S, Collins SP. Metabolomics of Prostate Cancer and Clinical Profiles Following Radiotherapy: Need for a Precision Phylometabolomics Approach. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243242

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmri, Hakima, Charles Sturgeon, David Posawatz, Mones Abu-Asab, Ryan R. Collins, Simeng Suy, and Sean P. Collins. 2025. "Metabolomics of Prostate Cancer and Clinical Profiles Following Radiotherapy: Need for a Precision Phylometabolomics Approach" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243242

APA StyleAmri, H., Sturgeon, C., Posawatz, D., Abu-Asab, M., Collins, R. R., Suy, S., & Collins, S. P. (2025). Metabolomics of Prostate Cancer and Clinical Profiles Following Radiotherapy: Need for a Precision Phylometabolomics Approach. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243242