Pericardial Fat Radiomics to Predict Left Ventricular Involvement and Provide Incremental Prognostic Value in ARVC

Abstract

1. Introduction

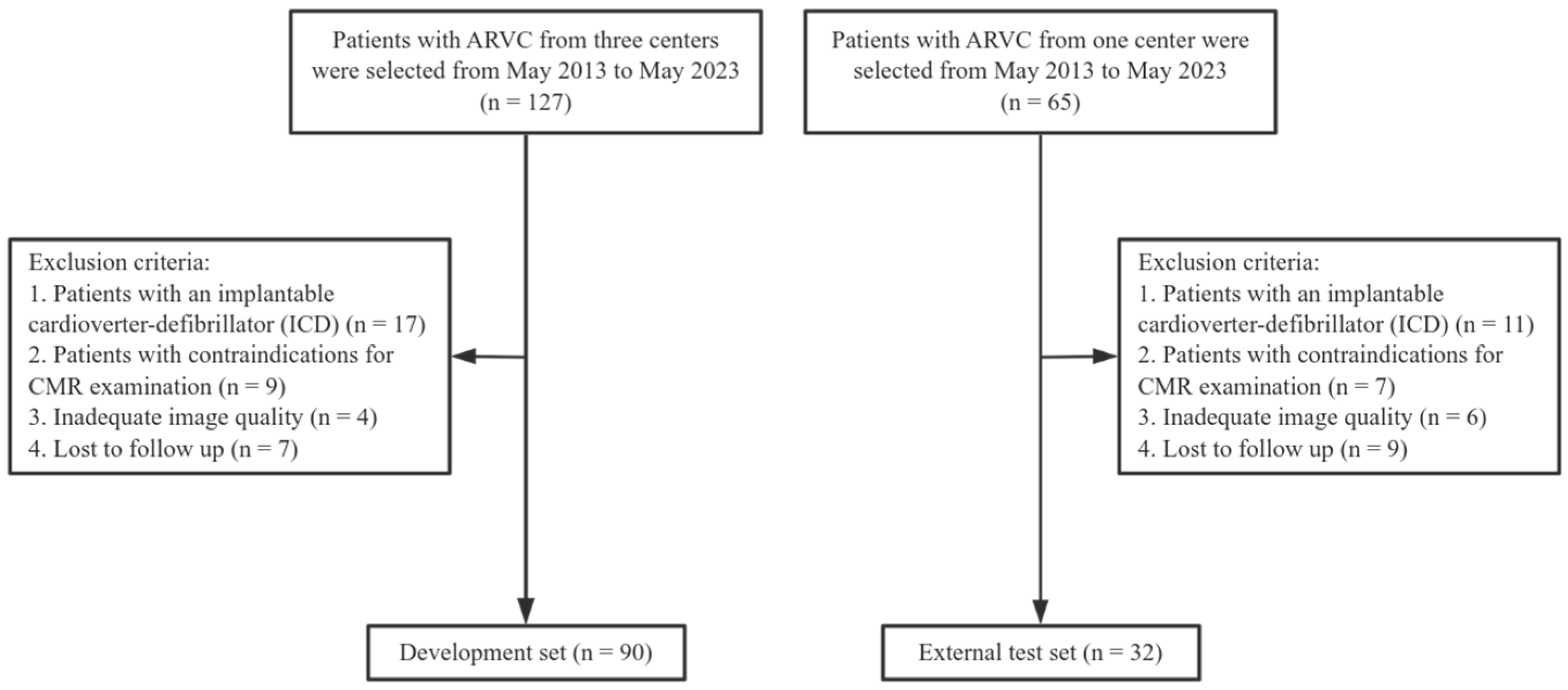

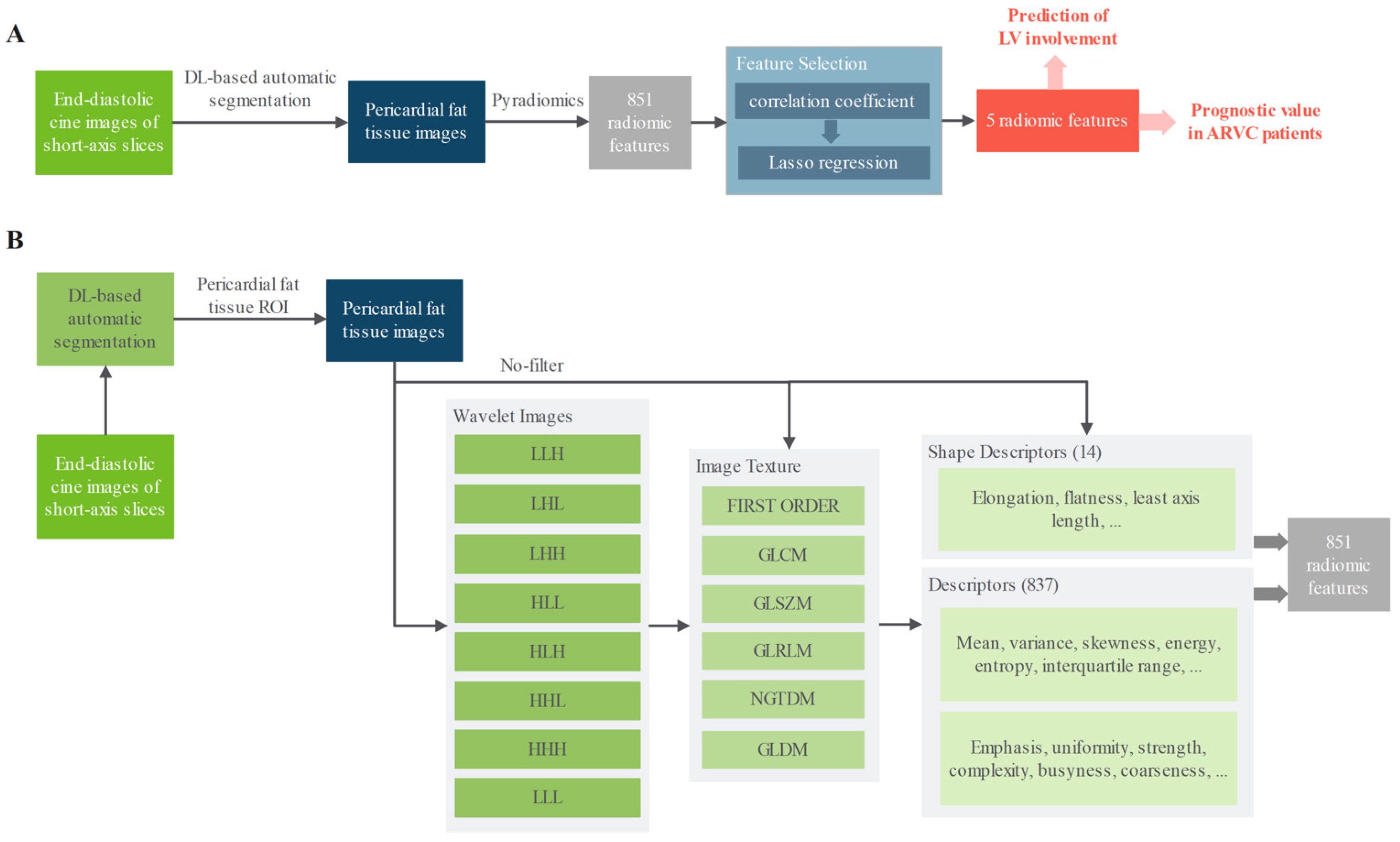

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

3.2. CMR Findings

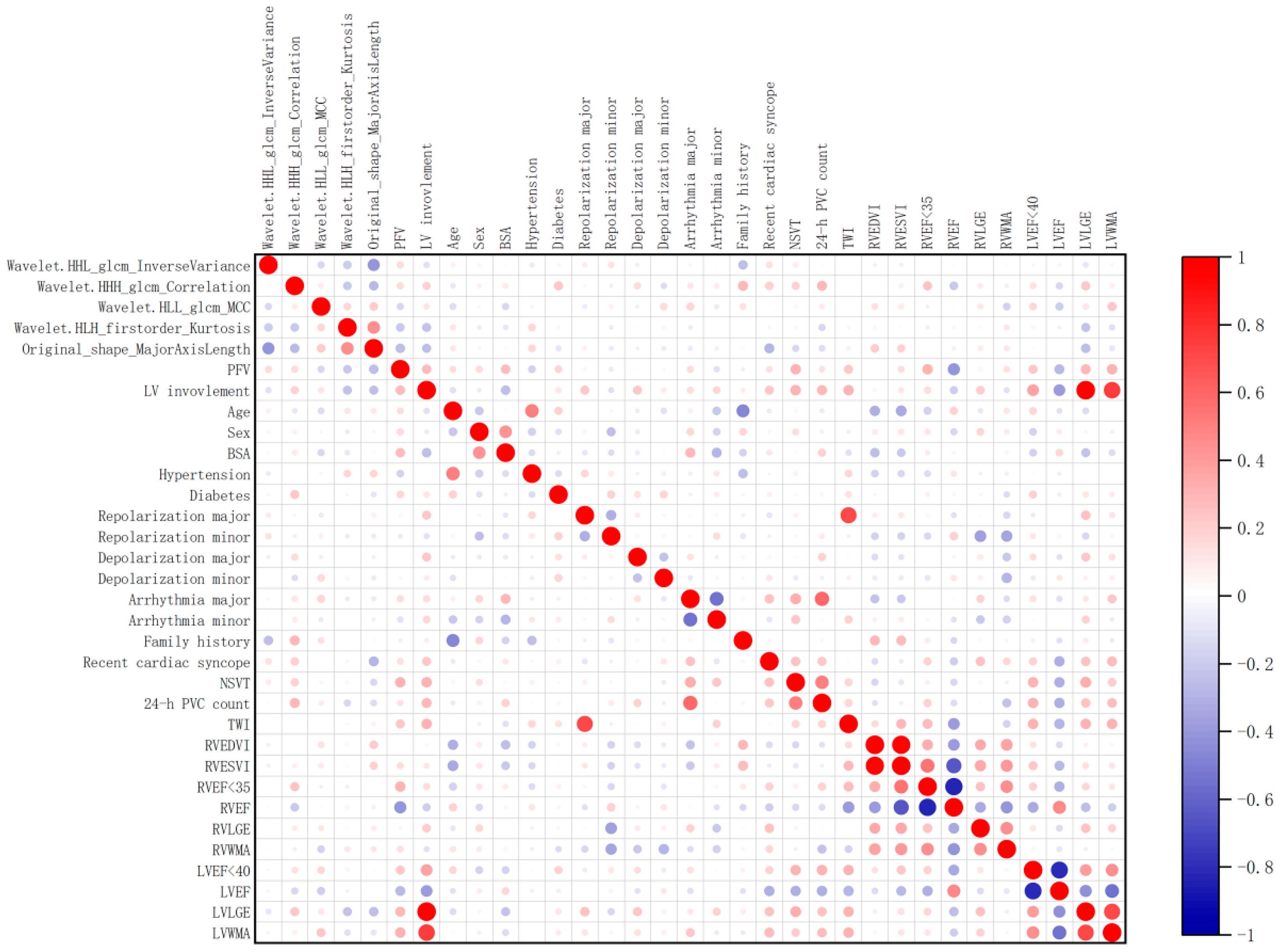

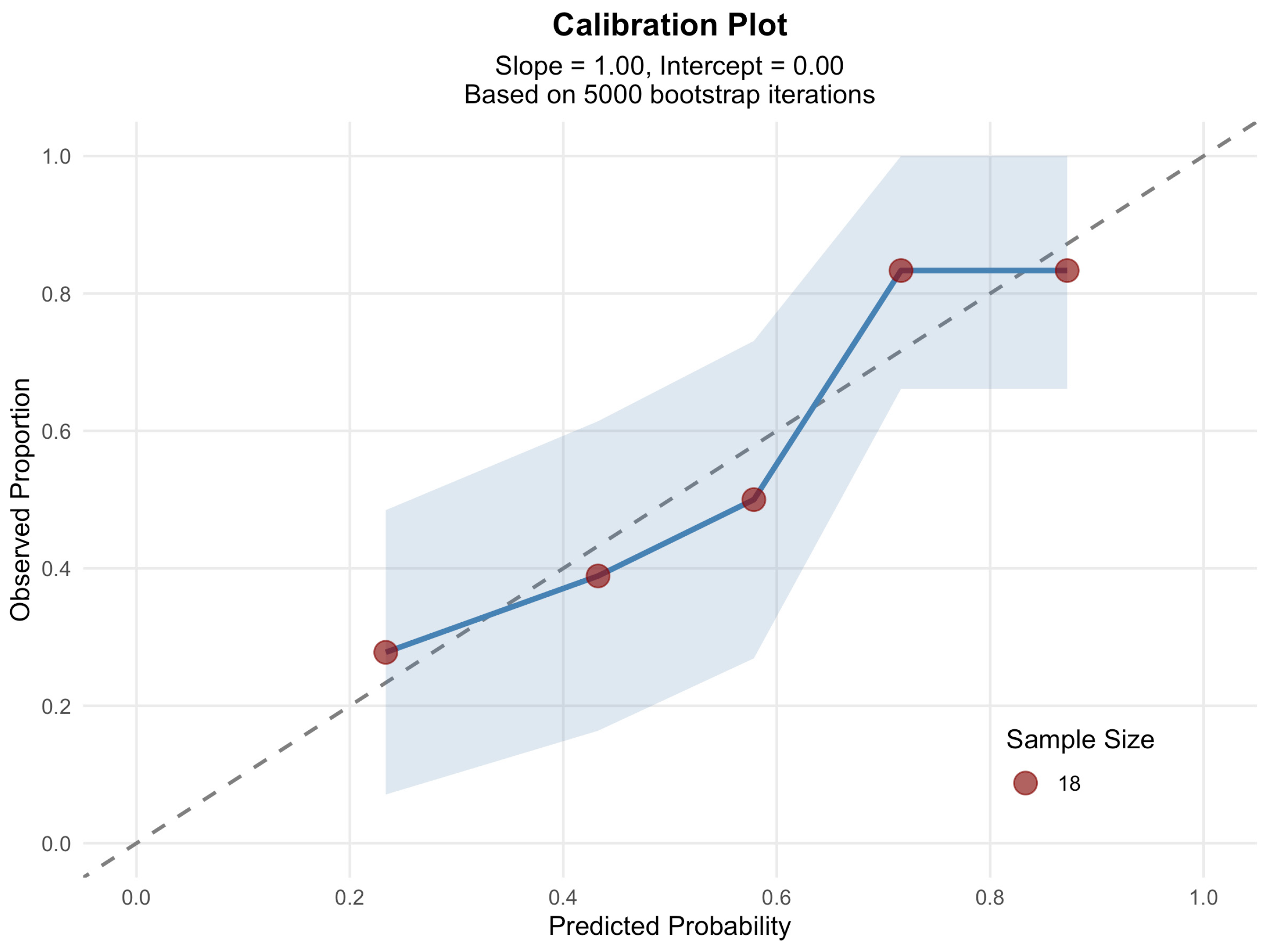

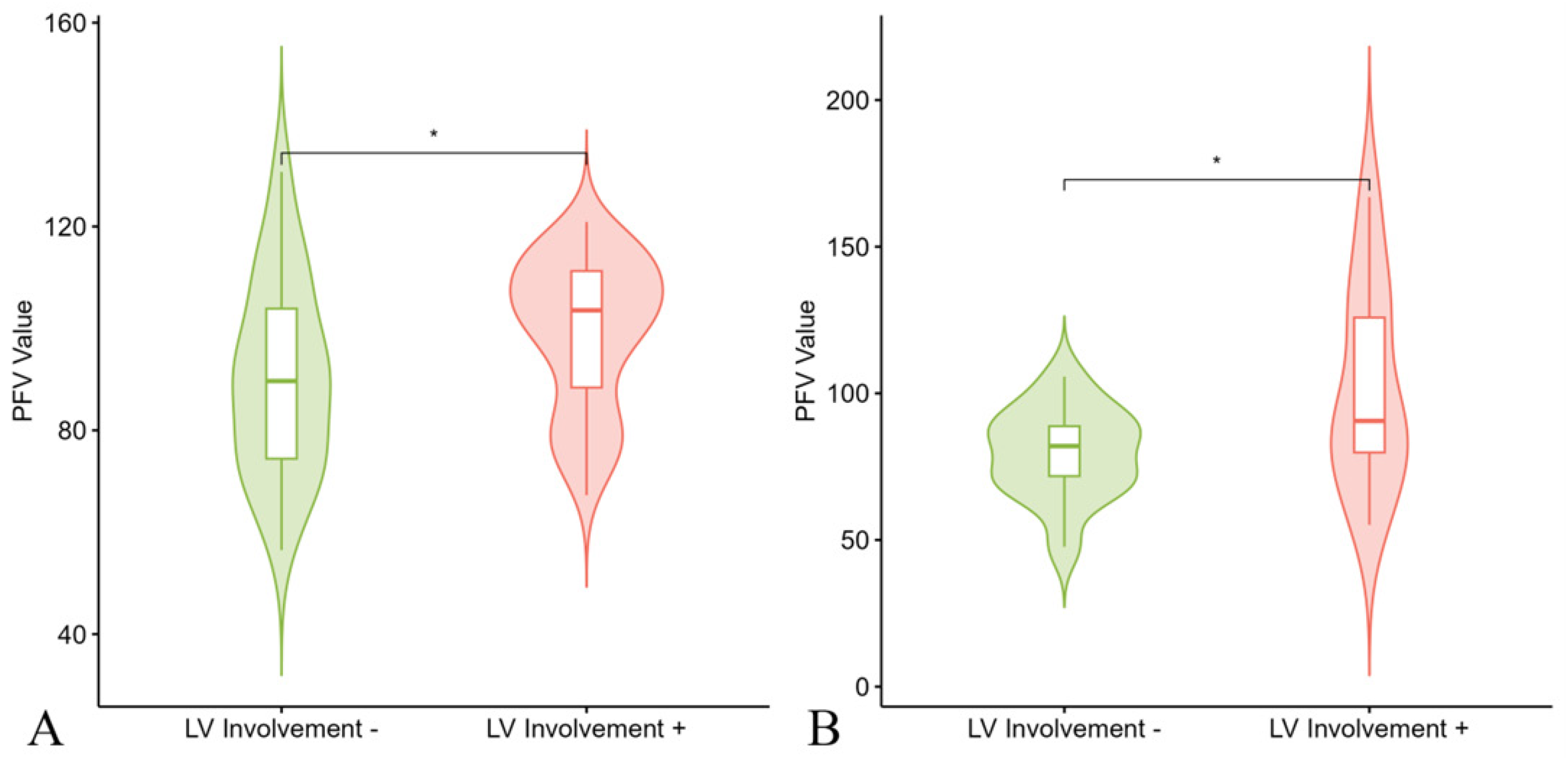

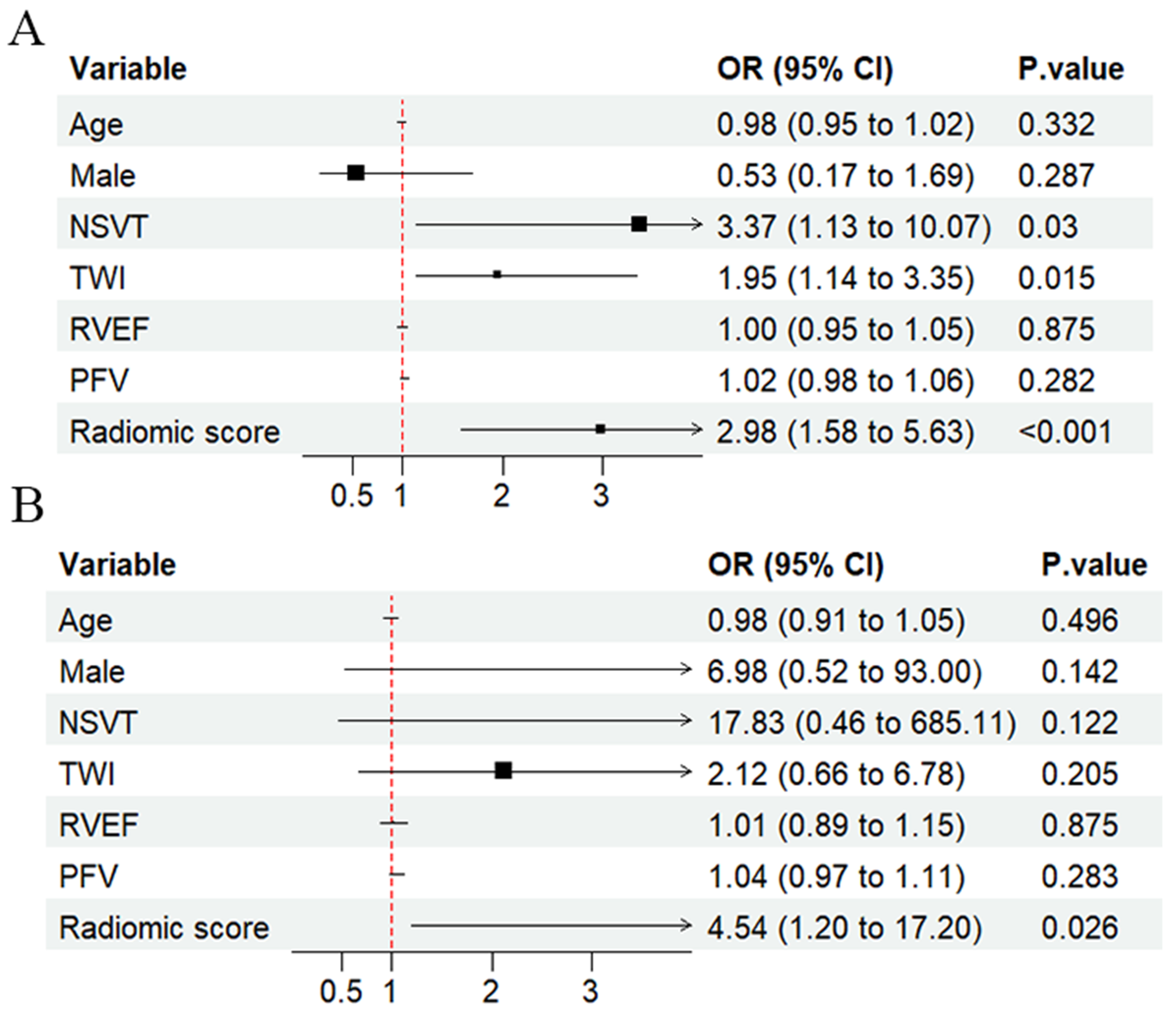

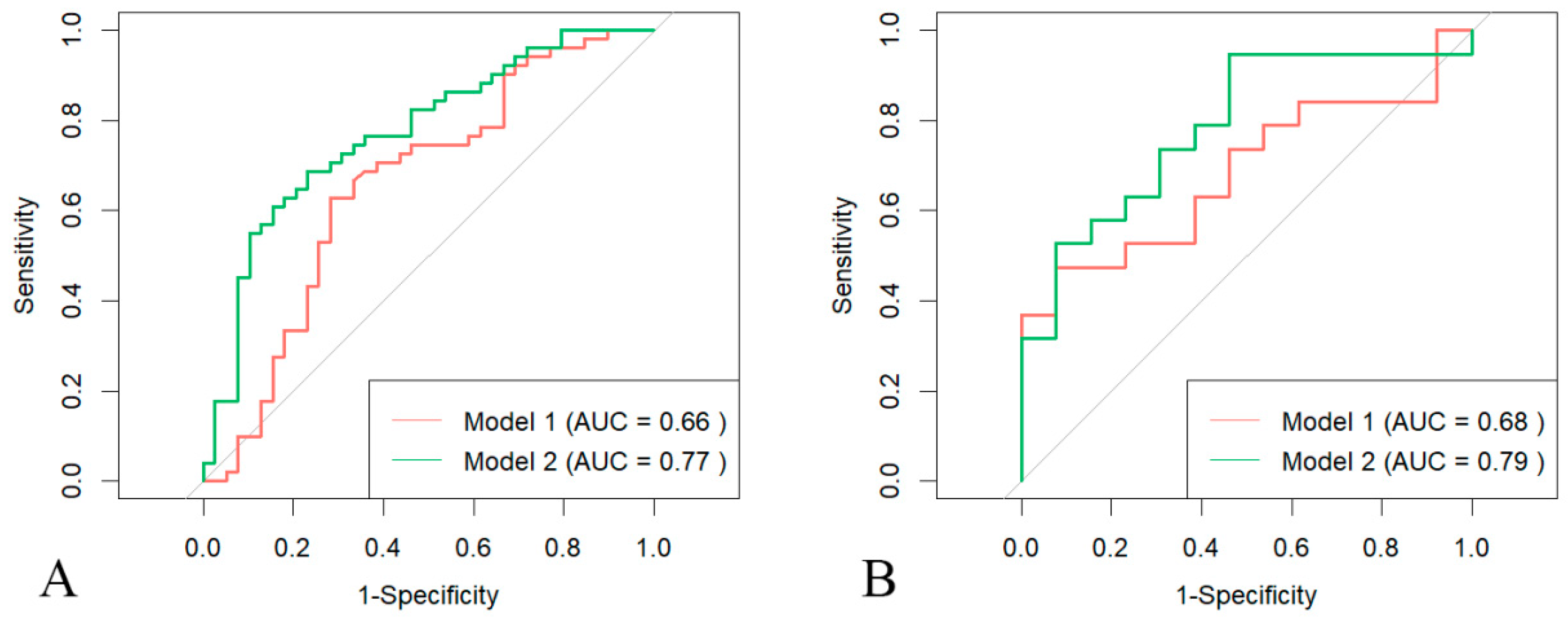

3.3. Prediction of LV Involvement

3.4. Prognostic Value of Pericardial Fat Tissue

3.5. Interobserver and Intraobserver Variability of Radiomic Features

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PFT | pericardial fat tissue |

| LV | left ventricular |

| ARVC | arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy |

| MACE | major adverse cardiac events |

| CMR | cardiac magnetic resonance |

| RS | radiomic score |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

| PFV | pericardial fat volume |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| RVEF | right ventricular ejection fraction |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. CMR Acquisition

- Ingenia, Philips, Best, The Netherlands

- MAGNETOM Skyra, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany

Appendix A.2. Pericardial Fat Tissue Analysis

| Characteristic | All Patients (n = 122) | Patients with MACE (n = 42) | Patients Without MACE (n = 80) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age (y) | 44 ± 17 | 48 ± 16 | 43 ± 17 | 0.114 |

| Male | 76/122 (62) | 25/42 (60) | 51/80 (64) | 0.647 |

| BSA | 1.68 ± 0.16 | 1.64 ± 0.15 | 1.70 ± 0.16 | 0.044 |

| Hypertension | 24/122 (20) | 6/42 (14) | 18/80 (23) | 0.278 |

| Diabetes | 6/122 (5) | 2/42 (5) | 4/80 (5) | 0.954 |

| Clinical presentation | ||||

| Recent cardiac syncope | 14/122 (12) | 9/42 (21) | 5/80 (6) | 0.012 |

| NSVT | 54/122 (44) | 29/42 (69) | 25/80 (31) | <0.001 |

| 24 h PVC count | 1803 (528–3406) | 2533 (1694–3846) | 990 (381–2934) | 0.003 |

| Leads with anterior and inferior TWI | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–3) | 1 (1–2) | <0.001 |

| 5 yr ARVC risk score | 0.24 (0.12–0.42) | 0.37 (0.23–0.58) | 0.19 (0.09–0.32) | <0.001 |

| Clinical phenotype | ||||

| Repolarization criteria | ||||

| Minor | 32/122 (26) | 12/42 (29) | 20/80 (25) | 0.670 |

| Major | 26/122 (21) | 8/42 (19) | 18/80 (23) | 0.658 |

| Depolarization criteria | ||||

| Minor | 50/122 (41) | 17/42 (41) | 33/80 (41) | 0.934 |

| Major | 11/122 (9) | 6/42 (14) | 5/80 (6) | 0.141 |

| Arrhythmia criteria | ||||

| Minor | 56/122 (46) | 22/42 (52) | 34/80 (43) | 0.298 |

| Major | 29/122 (24) | 9/42 (21) | 20/80 (25) | 0.660 |

| Structural criteria | ||||

| Minor | 43/122 (35) | 12/42 (29) | 31/80 (39) | 0.264 |

| Major | 96/122 (79) | 33/42 (79) | 63/80 (79) | 0.982 |

| Family history | 29/122 (24) | 14/42 (33) | 15/80 (19) | 0.072 |

| CMR Parameters | ||||

| LVEF | 49.18 ± 14.11 | 36.27 ± 14.06 | 55.96 ± 8.21 | <0.001 |

| LV LGE presence | 66/122 (54) | 33/42 (79) | 33/80 (41) | <0.001 |

| LV WMA | 45/122 (37) | 25/42 (60) | 20/80 (25) | <0.001 |

| RVEF | 31.87 ± 14.20 | 23.10 ± 11.16 | 36.47 ± 13.48 | <0.001 |

| RV LGE presence | 76/122 (62) | 31/42 (74) | 45/80 (56) | 0.057 |

| RV WMA | 95/122 (78) | 34/42 (81) | 61/80 (76) | 0.552 |

| RVEDVI (mL/m2) | 118.78 ± 49.53 | 136.99 ± 67.64 | 109.22 ± 33.37 | 0.015 |

| RVESVI (mL/m2) | 84.17 ± 45.43 | 105.23 ± 59.04 | 73.12 ± 31.51 | 0.002 |

| PFV | 94.66 ± 21.13 | 100.61 ± 24.62 | 91.54 ± 18.67 | 0.024 |

| AUC (95% CI) | p Value | Accuracy (%; [95% CI]) | Sensitivity (%; [95% CI]) | Specificity (%; [95% CI]) | F1 Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development Set | ||||||

| PFV model | 0.658 [0.539–0.777] | … | 66.67 (60/90; [57.78–76.67]) | 74.42 [62.35–88.37] | 59.57 [45.82–73.32] | 0.681 |

| RS model | 0.771 [0.672–0.870] | 0.051 | 72.22 (63/90; [63.33–81.11]) | 79.55 [67.98–91.74] | 65.22 [51.86–80.43] | 0.737 |

| External Test Set | ||||||

| PFV model | 0.684 [0.497–0.871] | … | 65.63 (21/32; [50.00–84.38]) | 90.00 [80.00–113.33] | 54.55 [34.09–75.76] | 0.621 |

| RS model | 0.785 [0.622–0.949] | 0.193 | 78.13 (25/32; [65.63–93.75]) | 75.00 [58.33–92.84] | 87.50 [75.00–115.00] | 0.837 |

| Prediction Model | C Index | Model 1 vs. Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Net Reclassification Index | p Value | ||

| Model 1: LV involvement + RVEF | 0.73 ± 0.07 | 0.136 (0.002–0.306) | <0.001 |

| Model 2: RS + RVEF | 0.76 ± 0.07 | ||

| Direct Effect | p Value | Indirect Effect | p Value | Mediated Proportion | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF | 0.186 (0.055, 0.310) | 0.002 | 0.133 (0.032, 0.250) | 0.008 | 0.415 (0.136, 0.740) | 0.008 |

| RVEF | 0.212 (0.049, 0.380) | 0.012 | 0.108 (0.039, 0.190) | <0.001 | 0.333 (0.119, 0.720) | 0.002 |

| PFT Radiomic Features | ICC | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Wavelet.HHL-GLCM-InverseVariance | 0.72 | [0.56–0.81] |

| Wavelet.HHH-GLCM-Correlation | 0.69 | [0.54–0.80] |

| Wavelet.HLL-GLCM-MCC | 0.74 | [0.58–0.83] |

| Wavelet.HLH-First Order-Kurtosis | 0.64 | [0.49–0.78] |

| Original-Shape-Major Axis Length | 0.77 | [0.55–0.84] |

| Observer 1 | Observer 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFT Radiomic Features | ICC | 95% CI | ICC | 95% CI |

| Wavelet.HHL-GLCM-InverseVariance | 0.67 | [0.52–0.80] | 0.81 | [0.68–0.87] |

| Wavelet.HHH-GLCM-Correlation | 0.72 | [0.53–0.81] | 0.73 | [0.53–0.84] |

| Wavelet.HLL-GLCM-MCC | 0.82 | [0.61–0.91] | 0.80 | [0.69–0.88] |

| Wavelet.HLH-First Order-Kurtosis | 0.69 | [0.50–0.79] | 0.77 | [0.63–0.90] |

| Original-Shape-Major Axis Length | 0.64 | [0.50–0.81] | 0.74 | [0.57–0.86] |

| Feature 1 | Feature 2 | Correlation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| wavelet.HHL_glcm_InverseVariance | original_shape_MajorAxisLength | −0.484 | Moderate |

| wavelet.HLH_firstorder_Kurtosis | original_shape_MajorAxisLength | 0.363 | Moderate |

| wavelet.HHH_glcm_Correlation | original_shape_MajorAxisLength | −0.32 | Moderate |

| wavelet.HHH_glcm_Correlation | wavelet.HLH_firstorder_Kurtosis | −0.266 | Weak |

| wavelet.HHL_glcm_InverseVariance | wavelet.HLH_firstorder_Kurtosis | −0.232 | Weak |

| wavelet.HLL_glcm_MCC | wavelet.HLH_firstorder_Kurtosis | 0.189 | Weak |

| wavelet.HLL_glcm_MCC | original_shape_MajorAxisLength | 0.177 | Weak |

| wavelet.HHL_glcm_InverseVariance | wavelet.HLL_glcm_MCC | −0.123 | Weak |

| wavelet.HHL_glcm_InverseVariance | wavelet.HHH_glcm_Correlation | 0.097 | Negligible |

| wavelet.HHH_glcm_Correlation | wavelet.HLL_glcm_MCC | 0.081 | Negligible |

References

- Gandjbakhch, E.; Redheuil, A.; Pousset, F.; Charron, P.; Frank, R. Clinical Diagnosis, Imaging, and Genetics of Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 784–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquaro, G.D.; De Luca, A.; Cappelletto, C.; Raimondi, F.; Bianco, F.; Botto, N.; Lesizza, P.; Grigoratos, C.; Minati, M.; Dell’oModarme, M.; et al. Prognostic Value of Magnetic Resonance Phenotype in Patients With Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2753–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquaro, G.D.; Pingitore, A.; Di Bella, G.; Piaggi, P.; Gaeta, R.; Grigoratos, C.; Altinier, A.; Pantano, A.; Strata, E.; De Caterina, R.; et al. Prognostic Role of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance in Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2018, 122, 1745–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinamonti, B.; Sinagra, G.; Salvi, A.; Di Lenarda, A.; Morgera, T.; Silvestri, F.; Bussani, R.; Camerini, F. Left ventricular involvement in right ventricular dysplasia. Am. Heart J. 1992, 123, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mast, T.P.; Teske, A.J.; vd Heijden, J.F.; Groeneweg, J.A.; Riele, A.S.T.; Velthuis, B.K.; Hauer, R.N.; Doevendans, P.A.; Cramer, M.J. Left Ventricular Involvement in Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy Assessed by Echocardiography Predicts Adverse Clinical Outcome. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1103–1113.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, O.; Sharma, A.; Ahmad, I.; Bourji, N.; Nestoiter, K.; Hua, P.; Hua, B.; Ivanov, A.; Yossef, J.; Klem, I.; et al. Correlation between pericardial, mediastinal, and intrathoracic fat volumes with the presence and severity of coronary artery disease, metabolic syndrome, and cardiac risk factors. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 16, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenchaiah, S.; Ding, J.; Carr, J.J.; Allison, M.A.; Budoff, M.J.; Tracy, R.P.; Burke, G.L.; McClelland, R.L.; Arai, A.E.; Bluemke, D.A. Pericardial Fat and the Risk of Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 2638–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polidori, T.; De Santis, D.; Rucci, C.; Tremamunno, G.; Piccinni, G.; Pugliese, L.; Zerunian, M.; Guido, G.; Pucciarelli, F.; Bracci, B.; et al. Radiomics applications in cardiac imaging: A comprehensive review. Radiol. Med. 2023, 128, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, F.I.; McKenna, W.J.; Sherrill, D.; Basso, C.; Bauce, B.; Bluemke, D.A.; Calkins, H.; Corrado, D.; Cox, M.G.; Daubert, J.P.; et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: Proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation 2010, 121, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.-Y.; Chen, B.-H.; Wu, R.; An, D.-A.; Shi, R.-Y.; Wu, C.-W.; Tang, L.-L.; Zhao, L.; Wu, L.-M. Prognostic value of right atrial strains in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Insights Imaging 2024, 15, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towbin, J.A.; McKenna, W.J.; Abrams, D.J.; Ackerman, M.J.; Calkins, H.; Darrieux, F.C.; Daubert, J.P.; de Chillou, C.; DePasquale, E.C.; Desai, M.Y.; et al. 2019 HRS expert consensus statement on evaluation, risk stratification, and management of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm 2019, 16, e301–e372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; An, D.; Feng, C.; Bian, Z.; Wu, L.M. Segmentation of Pericardial Adipose Tissue in CMR Images: A Benchmark Dataset MRPEAT and a Triple-Stage Network 3SUnet. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2023, 42, 2386–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Griethuysen, J.J.; Fedorov, A.; Parmar, C.; Hosny, A.; Aucoin, N.; Narayan, V.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Fillion-Robin, J.-C.; Pieper, S.; Aerts, H.J.W.L. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, e104–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V.Y.; Dey, D.; Tamarappoo, B.; Nakazato, R.; Gransar, H.; Miranda-Peats, R.; Ramesh, A.; Wong, N.D.; Shaw, L.J.; Slomka, P.J.; et al. Pericardial fat burden on ECG-gated noncontrast CT in asymptomatic patients who subsequently experience adverse cardiovascular events. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2010, 3, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperetti, A.; Carrick, R.T.; Costa, S.; Compagnucci, P.; Bosman, L.P.; Chivulescu, M.; Tichnell, C.; Murray, B.; Tandri, H.; Tadros, R.; et al. Programmed Ventricular Stimulation as an Additional Primary Prevention Risk Stratification Tool in Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy: A Multinational Study. Circulation 2022, 146, 1434–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadrin-Tourigny, J.; Bosman, L.P.; Nozza, A.; Wang, W.; Tadros, R.; Bhonsale, A.; Bourfiss, M.; Fortier, A.; Lie, Ø.H.; Saguner, A.M.; et al. A new prediction model for ventricular arrhythmias in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zghaib, T.; Te Riele, A.S.J.M.; James, C.A.; Rastegar, N.; Murray, B.; Tichnell, C.; Halushka, M.K.; Bluemke, D.A.; Tandri, H.; Calkins, H.; et al. Left ventricular fibro-fatty replacement in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy: Prevalence, patterns, and association with arrhythmias. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2021, 23, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmayer, S.; Nazarian, S.; Han, Y.C. Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC): Can We Separate ARVC From Other Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathies? J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e018866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdis, D.; Chen, L.; Saguner, A.M.; Zhang, N.; Gawinecka, J.; Saleh, L.; von Eckardstein, A.; Ren, J.; Matter, C.M.; Hu, Z.; et al. Novel plasma biomarkers predicting biventricular involvement in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am. Heart J. 2022, 244, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelletti, S.; Vischer, A.S.; Syrris, P.; Crotti, L.; Spazzolini, C.; Ghidoni, A.; Parati, G.; Jenkins, S.; Kotta, M.-C.; McKenna, W.J.; et al. Desmoplakin missense and non-missense mutations in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: Genotype-phenotype correlation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 249, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmermund, B.N.; Rieth, A.J.; Rademann, M.; Borst, P.C.; Kriechbaum, S.D.; Wolter, J.S.; Schuster, A.; Wiedenroth, C.B.; Treiber, J.M.; Rolf, A.; et al. Abnormal Left Atrial Strain by CMR Is Associated With Left Heart Disease in Patients With Pulmonary Hypertension. Circ.-Heart Fail. 2025, 18, e013480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamani, S.K.; Sarma, S.; MacNamara, J.P.; Hynan, L.S.; Haykowsky, M.J.; Hearon, C.M.; Wakeham, D.; Brazile, T.; Levine, B.D.; Zaha, V.G.; et al. Excess Pericardial Fat Is Related to Adverse Cardio-Mechanical Interaction in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation 2023, 148, 1410–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit-Verheggen, V.H.W.; Altintas, S.; Spee, R.J.M.; Mihl, C.; van Kuijk, S.M.J.; Wildberger, J.E.; Schrauwen-Hinderling, V.B.; Kietselaer, B.L.J.H.; van de Weijer, T. Pericardial fat and its influence on cardiac diastolic function. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Putt, M.E.; Yang, W.; Bertoni, A.G.; Ding, J.; Lima, J.A.; Allison, M.A.; Barr, R.G.; Al-Naamani, N.; Patel, R.B.; et al. Association of Pericardial Fat with Cardiac Structure, Function, and Mechanics: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2022, 35, 579–587.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, T.; Zhang, L.; Zalewski, A.; Mannion, J.D.; Diehl, J.T.; Arafat, H.; Sarov-Blat, L.; O’Brien, S.; Keiper, E.A.; Johnson, A.G.; et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue is a source of inflammatory mediators. Circulation 2003, 108, 2460–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohela, A.; van Kampen, S.J.; Moens, T.; Wehrens, M.; Molenaar, B.; Boogerd, C.J.; Monshouwer-Kloots, J.; Perini, I.; Goumans, M.J.; Smits, A.M.; et al. Epicardial differentiation drives fibro-fatty remodeling in arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabf2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rawahi, M.; Proietti, R.; Thanassoulis, G. Pericardial fat and atrial fibrillation: Epidemiology, mechanisms and interventions. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 195, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teske, A.J.; Mast, T.P. Moving From Multimodality Diagnostic Tests Toward Multimodality Risk Stratification in ARVC. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 10, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protonotarios, A.; Bariani, R.; Cappelletto, C.; Pavlou, M.; García-García, A.; Cipriani, A.; Protonotarios, I.; Rivas, A.; Wittenberg, R.; Graziosi, M.; et al. Importance of genotype for risk stratification in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy using the 2019 ARVC risk calculator. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3053–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauriello, A.; Correra, A.; Maratea, A.C.; Caturano, A.; Liccardo, B.; Perrone, M.A.; Giordano, A.; Nigro, G.; D’andrea, A.; Russo, V. Serum Lipids, Inflammation, and the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation: Pathophysiological Links and Clinical Evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Development Set (n = 90 Patients) | External Test Set (n = 32 Patients) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age (y) | 46 ± 16 | 40 ± 17 | 0.110 |

| Male | 57/90 (63) | 19/32 (59) | 0.691 |

| BSA | 1.65 ± 0.15 | 1.75 ± 0.18 | 0.010 |

| Hypertension | 21/90 (23) | 3/32 (9) | 0.088 |

| Diabetes | 5/90 (6) | 1/32 (3) | 0.585 |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Recent cardiac syncope | 10/90 (11) | 4/32 (13) | 0.832 |

| NSVT | 41/90 (46) | 13/32 (41) | 0.630 |

| 24 h PVC count | 1503 (390–3061) | 2453 (936–3793) | 0.037 |

| Leads with anterior and inferior TWI | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.881 |

| 5 yr ARVC risk score | 0.23 (0.12–0.41) | 0.24 (0.13–0.45) | 0.710 |

| Clinical phenotype | |||

| Repolarization criteria | |||

| Minor | 23/90 (26) | 9/32 (28) | 0.777 |

| Major | 19/90 (21) | 7/32 (22) | 0.928 |

| Depolarization criteria | |||

| Minor | 39/90 (43) | 11/32 (34) | 0.376 |

| Major | 6/90 (7) | 5/32 (16) | 0.129 |

| Arrhythmia criteria | |||

| Minor | 39/90 (43) | 17/32 (53) | 0.340 |

| Major | 25/90 (28) | 4/32 (13) | 0.081 |

| Structural criteria | |||

| Minor | 35/90 (39) | 8/32 (25) | 0.158 |

| Major | 74/90 (82) | 22/32 (69) | 0.110 |

| Family history | 22/90 (24) | 7/32 (22) | 0.769 |

| CMR parameters | |||

| LVEF | 48.17 ± 14.63 | 52.03 ± 12.31 | 0.185 |

| LV LGE presence | 50/90 (56) | 16/32 (50) | 0.588 |

| LV WMA | 38/90 (42) | 7/32 (22) | 0.040 |

| RVEF | 31.13 ± 12.83 | 33.95 ± 17.55 | 0.410 |

| RV LGE presence | 59/90 (66) | 17/32 (53) | 0.213 |

| RV WMA | 72/90 (80) | 23/32 (72) | 0.342 |

| RVEDVI (mL/m2) | 119.86 ± 44.95 | 115.73 ± 61.32 | 0.687 |

| RVESVI (mL/m2) | 85.05 ± 41.29 | 81.70 ± 56.14 | 0.721 |

| PFV | 95.31 ± 17.12 | 92.84 ± 29.96 | 0.661 |

| Development Set (n = 90 Patients) | External Test Set (n = 32 Patients) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | AUC | 95% CI | AUC | 95% CI |

| Recent cardiac syncope | 0.575 | 0.517–0.634 | 0.605 | 0.511–0.699 |

| NSVT | 0.653 | 0.554–0.752 | 0.713 | 0.560–0.866 |

| 24 h PVC count | 0.718 | 0.605–0.831 | 0.623 | 0.418–0.829 |

| Leads with anterior and inferior TWI | 0.677 | 0.568–0.787 | 0.692 | 0.510–0.874 |

| RVEF | 0.605 | 0.480–0.730 | 0.648 | 0.449–0.846 |

| RV LGE presence | 0.603 | 0.504–0.703 | 0.753 | 0.596–0.910 |

| RV WMA | 0.459 | 0.377–0.541 | 0.457 | 0.297–0.618 |

| RVEDVI (mL/m2) | 0.546 | 0.425–0.666 | 0.688 | 0.496–0.880 |

| RVESVI (mL/m2) | 0.583 | 0.462–0.704 | 0.773 | 0.595–0.951 |

| PFV | 0.658 | 0.539–0.777 | 0.684 | 0.497–0.871 |

| RS | 0.771 | 0.672–0.870 | 0.785 | 0.622–0.949 |

| Univariate Analyses | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | p Value | HR * | p Value |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age (y) | 1.009 (0.991–1.028) | 0.338 | … | … |

| Male | 0.805 (0.434–1.494) | 0.492 | … | … |

| BSA | 0.225 (0.030–1.664) | 0.144 | … | … |

| Hypertension | 0.546 (0.230–1.300) | 0.172 | … | … |

| Diabetes | 1.479 (0.352–6.225) | 0.593 | … | … |

| Clinical presentation | ||||

| Recent cardiac syncope | 2.308 (1.103–4.827) | 0.026 | 3.091 (1.412–6.766) | 0.005 |

| NSVT | 3.713 (1.920–7.180) | <0.001 | 4.027 (2.027–7.999) | <0.001 |

| 24 h PVC count | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 0.001 | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | <0.001 |

| Leads with anterior and inferior TWI | 1.424 (1.179–1.721) | <0.001 | 1.692 (1.347–2.124) | <0.001 |

| 5 yr ARVC risk score | 13.431 (4.224–42.706) | <0.001 | 64.847 (15.402–273.023) | <0.001 |

| CMR parameters | ||||

| LVEF | 0.942 (0.925–0.959) | <0.001 | 0.942 (0.924–0.961) | <0.001 |

| LV LGE presence | 3.409 (1.628–7.138) | 0.001 | 3.499 (1.632–7.500) | 0.001 |

| LV WMA | 2.353 (1.265–4.379) | 0.007 | 2.245 (1.179–4.276) | 0.014 |

| RVEF | 0.942 (0.917–0.968) | <0.001 | 0.938 (0.914–0.964) | <0.001 |

| RV LGE presence | 1.540 (0.774–3.066) | 0.219 | 1.507 (0.748–3.038) | 0.251 |

| RV WMA | 1.310 (0.606–2.832) | 0.493 | 1.147 (0.507–2.598) | 0.742 |

| RVEDVI (mL/m2) | 1.012 (1.006–1.019) | <0.001 | 1.012 (1.005–1.019) | 0.001 |

| RVESVI (mL/m2) | 1.014 (1.007–1.021) | <0.001 | 1.016 (1.008–1.024) | <0.001 |

| PFV | 1.017 (1.002–1.032) | 0.024 | 1.017 (1.002–1.033) | 0.027 |

| RS | 3.452 (1.778–6.703) | <0.001 | 3.723 (1.872–7.401) | <0.001 |

| Prediction Model | C Index | Net Reclassification Index | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: 5-year ARVC risk score | 0.70 ± 0.08 | NA | |

| Model 2: RS | 0.67 ± 0.10 | NA | |

| Model 3: model 1 + model 2 | 0.73 ± 0.08 | Model 1 vs. Model 3 | |

| 0.079 (0.018–0.412) | <0.001 | ||

| Model 2 vs. Model 3 | |||

| 0.315 (0.033–0.468) | <0.001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, M.; Zheng, J.; Xie, W.; Chen, B.; An, D.; Shi, R.; Xiang, J.; Wu, L. Pericardial Fat Radiomics to Predict Left Ventricular Involvement and Provide Incremental Prognostic Value in ARVC. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3240. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243240

Guo M, Zheng J, Xie W, Chen B, An D, Shi R, Xiang J, Wu L. Pericardial Fat Radiomics to Predict Left Ventricular Involvement and Provide Incremental Prognostic Value in ARVC. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3240. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243240

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Mengqi, Jinyu Zheng, Weihui Xie, Binghua Chen, Dongaolei An, Ruoyang Shi, Jinyi Xiang, and Lianming Wu. 2025. "Pericardial Fat Radiomics to Predict Left Ventricular Involvement and Provide Incremental Prognostic Value in ARVC" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3240. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243240

APA StyleGuo, M., Zheng, J., Xie, W., Chen, B., An, D., Shi, R., Xiang, J., & Wu, L. (2025). Pericardial Fat Radiomics to Predict Left Ventricular Involvement and Provide Incremental Prognostic Value in ARVC. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3240. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243240