Advancements in Renal Imaging: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of PET Probes for Enhanced GFR and Renal Perfusion Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Screening and Data Extraction

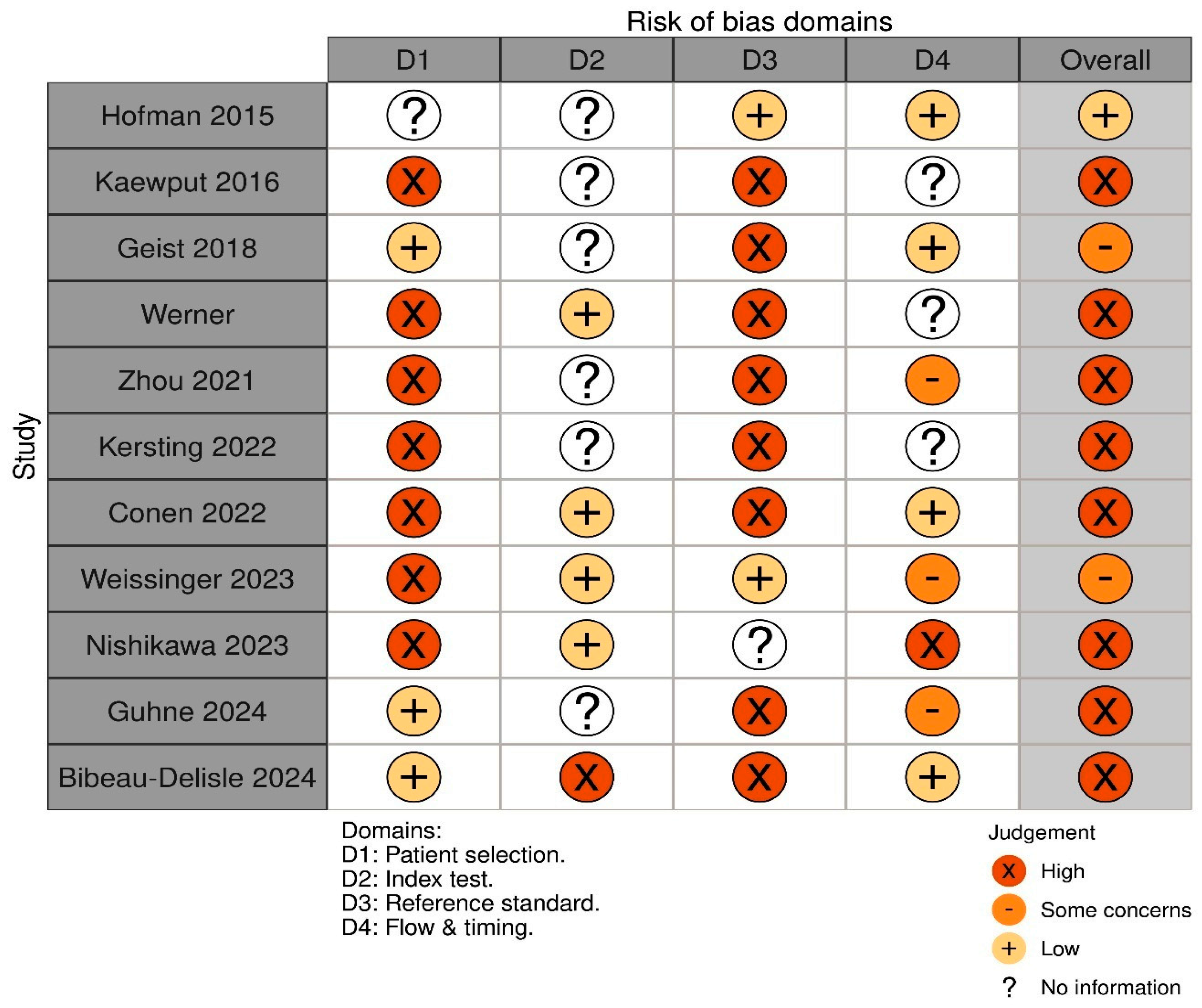

2.4. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

4. Systematic Review

4.1. 68Ga-Labelled Radiotracers for Renal Functional Imaging

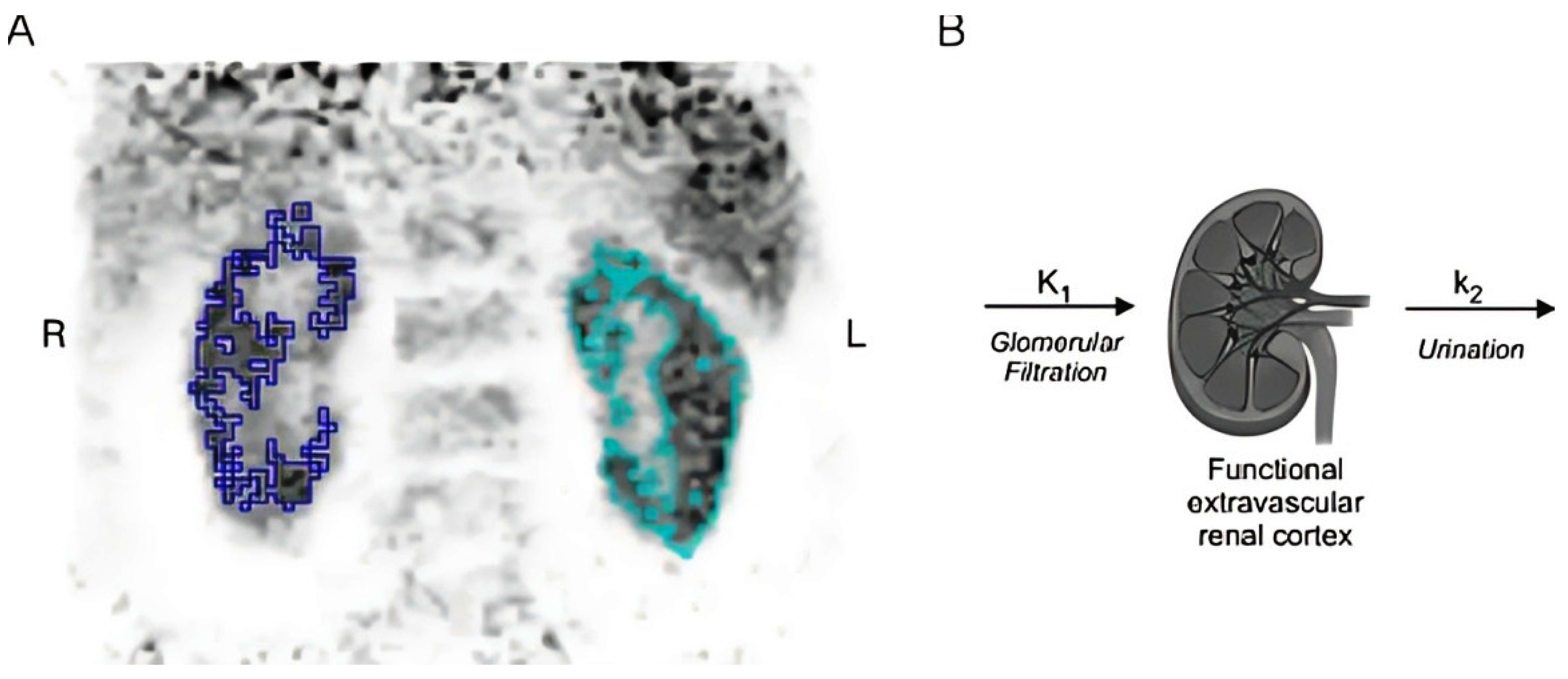

4.1.1. 68Ga-EDTA

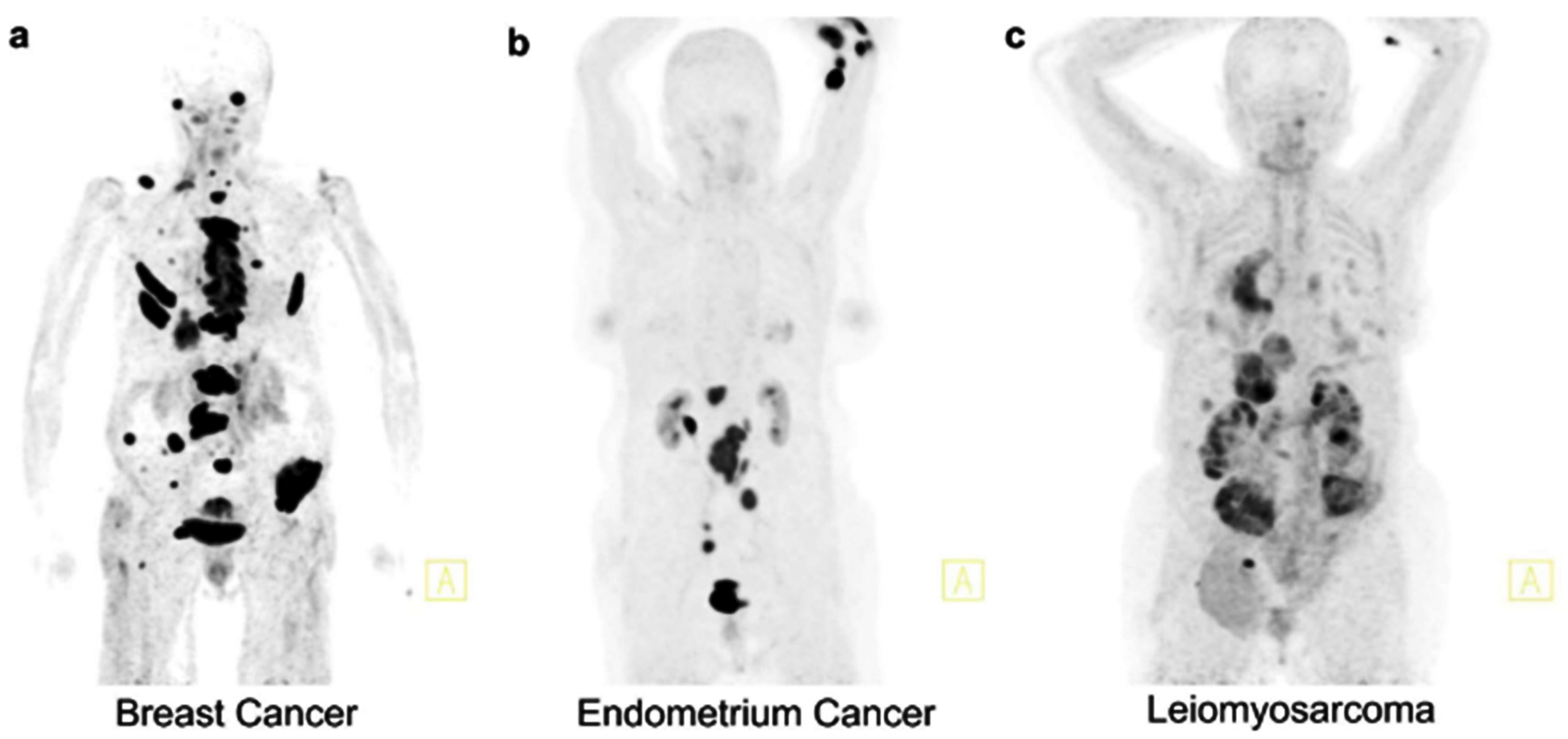

4.1.2. 68Ga-DOTANOC, 68Ga-ha DOTATATE

4.1.3. 68Ga-PSMA-11

4.1.4. 68Ga-FAPI

4.2. 18F-Labelled Radiotracers

4.2.1. Dynamic 18F-FDG-PET/MRI

4.2.2. 2[18F]-FDS (2-Deoxy-2-18F-Fluoro-D-Sorbitol)

4.3. Other Tracers

4.3.1. 82Rb-PET

4.3.2. 64Cu-ATSM PET/MRI

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GFR | Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| SUV | Standardized Uptake Value |

| SUVmax | Maximum Standardized Uptake Value |

| SUVmean | Mean Standardized Uptake Value |

| TAC | Time–Activity Curve |

| TER | Tubular Extraction Rate |

| TKA | Total Kidney Accumulation |

| TLG | Total Lesion Glycolysis |

| TLGSUL | Total Lesion Glycolysis corrected for Lean Body Mass (SUL) |

| VOI | Volume of Interest |

| 18F-FDG | 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose |

| 18F-FDS | 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-sorbitol |

| 51Cr-EDTA | Chromium-51 ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| 64Cu-ATSM | Copper-64 diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) |

| 68Ga | Gallium-68 |

| 68Ga-DOTA | Gallium-68 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid |

| 68Ga-DOTANOC | Gallium-68 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid-1-Nal3-octreotide |

| 68Ga-EDTA | Gallium-68 ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| 68Ga-FAPI | Gallium-68 Fibroblast Activation Protein Inhibitor |

| 68Ga-ha DOTATATE | Gallium-68 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid-Tyr3-octreotate |

| 68Ga-PSMA-11 | Gallium-68 prostate-specific membrane antigen-11 |

| 82Rb-RbCl | Rubidium-82 Rubidium Chloride |

| 90Y | Yttrium-90 |

| 99ᵐTc-DTPA | Technetium-99m diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid |

| 99ᵐTc-MAG3 | Technetium-99m mercaptoacetyltriglycine |

| ACI | Accumulation Index |

| ASL-MRI | Arterial Spin Labeling Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| BSA | Body Surface Area |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CKD-EPI | Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| eGFR | Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| ERPF | Effective Renal Plasma Flow |

| FAP | Fibroblast Activation Protein |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| NET | Neuroendocrine Tumor |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PCC | Pearson Correlation Coefficient |

| SPECT | Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography |

| SSR | Somatostatin Receptor |

| PRRT | Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy |

| RBF | Renal Blood Flow |

| ASL-MRI | Arterial Spin Labeling MRI |

References

- Toyama, Y.; Werner, R.A.; Ruiz-Bedoya, C.A.; Ordonez, A.A.; Takase, K.; Lapa, C.; Jain, S.K.; Pomper, M.G.; Rowe, S.P.; Higuchi, T. Current and Future Perspectives on Functional Molecular Imaging in Nephro-Urology: Theranostics on the Horizon. Theranostics 2021, 11, 6105–6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skytte Larsson, J.; Krumbholz, V.; Enskog, A.; Bragadottir, G.; Redfors, B.; Ricksten, S.-E. Renal Blood Flow, Glomerular Filtration Rate, and Renal Oxygenation in Early Clinical Septic Shock. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, e560–e566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soveri, I.; Berg, U.B.; Björk, J.; Elinder, C.-G.; Grubb, A.; Mejare, I.; Sterner, G.; Bäck, S.-E. SBU GFR Review Group Measuring GFR: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2014, 64, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.J.; Furth, S.L. Glomerular Filtration Rate Measurement and Estimation in Chronic Kidney Disease. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2007, 22, 1839–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanaye, P.; Melsom, T.; Ebert, N.; Bäck, S.-E.; Mariat, C.; Cavalier, E.; Björk, J.; Christensson, A.; Nyman, U.; Porrini, E.; et al. Iohexol Plasma Clearance for Measuring Glomerular Filtration Rate in Clinical Practice and Research: A Review. Part 2: Why to Measure Glomerular Filtration Rate with Iohexol? Clin. Kidney J. 2016, 9, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, M.; Mora Sánchez, M.G.; Bernal Amador, A.S.; Paniagua, R. The Metabolism of Creatinine and Its Usefulness to Evaluate Kidney Function and Body Composition in Clinical Practice. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, J.S.; Wilkinson, J.; Oliver, R.M.; Ackery, D.M.; Blake, G.M.; Waller, D.G. Comparison of Radionuclide Estimation of Glomerular Filtration Rate Using Technetium 99m Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic Acid and Chromium 51 Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1991, 18, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weindler, J.; Ali, M.; Udovicich, C.; Hofman, M.S.; Siva, S. Novel Radiopharmaceuticals for Molecular Imaging of Renal Cell Carcinoma. BMJ Oncol. 2025, 4, e000645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, B.K. Calculation of GFR via the Slope-Intercept Method in Nuclear Medicine. In Glomerulonephritis and Nephrotic Syndrome; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78984-314-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hofman, M.S.; Hicks, R.J. Gallium-68 EDTA PET/CT for Renal Imaging. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2016, 46, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündel, D.; Pohle, U.; Prell, E.; Odparlik, A.; Thews, O. Assessing Glomerular Filtration in Small Animals Using [68Ga]DTPA and [68Ga]EDTA with PET Imaging. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2018, 20, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakabayashi, H.; Werner, R.A.; Hayakawa, N.; Javadi, M.S.; Xinyu, C.; Herrmann, K.; Rowe, S.P.; Lapa, C.; Higuchi, T. Initial Preclinical Evaluation of 18F-Fluorodeoxysorbitol PET as a Novel Functional Renal Imaging Agent. J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 1625–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Jiang, D.; Liu, Y.; Cao, W. Glomerular Filtration Rate Calculation Based on 68Ga-EDTA Dynamic Renal PET. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 12, 54–62. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33782057/ (accessed on 11 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Rayyan: AI-Powered Systematic Review Management Platform. Available online: https://www.rayyan.ai/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- QUADAS-2: A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22007046/ (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Geist, B.K.; Baltzer, P.; Fueger, B.; Hamboeck, M.; Nakuz, T.; Papp, L.; Rasul, S.; Sundar, L.K.S.; Hacker, M.; Staudenherz, A. Assessing the Kidney Function Parameters Glomerular Filtration Rate and Effective Renal Plasma Flow with Dynamic FDG-PET/MRI in Healthy Subjects. EJNMMI Res. 2018, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

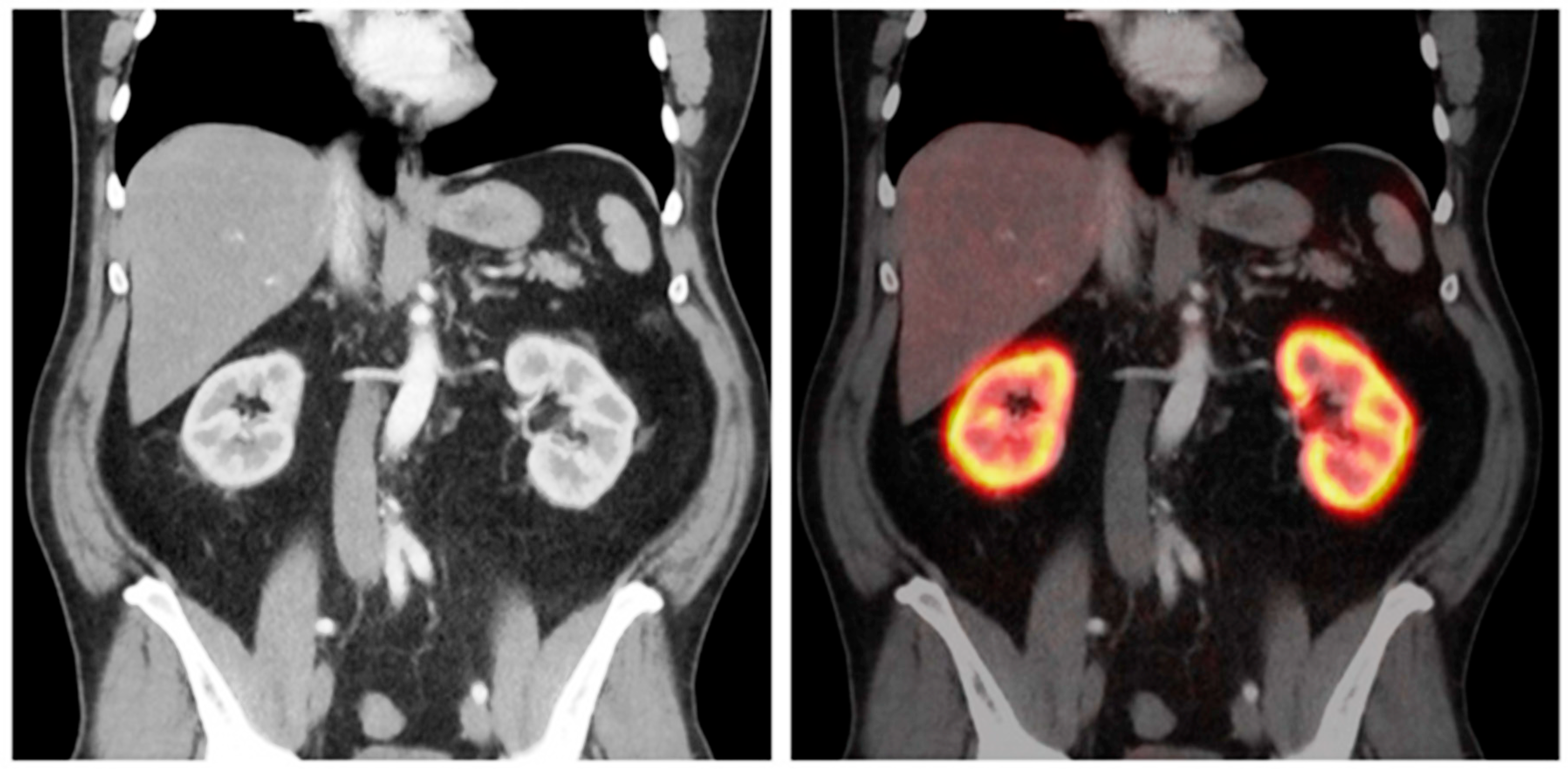

- Nishikawa, Y.; Takahashi, N.; Nishikawa, S.; Shimamoto, Y.; Nishimori, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Kimura, H.; Tsujikawa, T.; Kasuno, K.; Mori, T.; et al. Feasibility of Renal Blood Flow Measurement Using 64Cu-ATSM PET/MRI: A Quantitative PET and MRI Study. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Luo, W.; Liu, H.; Lv, T.; Wang, J.; Qin, J.; Ou, S.; Chen, Y. Value of [68Ga]Ga-FAPI-04 Imaging in the Diagnosis of Renal Fibrosis. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2021, 48, 3493–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kersting, D.; Sraieb, M.; Seifert, R.; Costa, P.F.; Kazek, S.; Kessler, L.; Umutlu, L.; Fendler, W.P.; Jentzen, W.; Herrmann, K.; et al. First Experiences with Dynamic Renal [68Ga]Ga-DOTA PET/CT: A Comparison to Renal Scintigraphy and Compartmental Modelling to Non-Invasively Estimate the Glomerular Filtration Rate. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 3373–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, M.; Binns, D.; Johnston, V.; Siva, S.; Thompson, M.; Eu, P.; Collins, M.; Hicks, R.J. 68Ga-EDTA PET/CT Imaging and Plasma Clearance for Glomerular Filtration Rate Quantification: Comparison to Conventional 51Cr-EDTA. J. Nucl. Med. Off. Publ. Soc. Nucl. Med. 2015, 56, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, R.A.; Ordonez, A.A.; Sanchez-Bautista, J.; Marcus, C.; Lapa, C.; Rowe, S.P.; Pomper, M.G.; Leal, J.P.; Lodge, M.A.; Javadi, M.S.; et al. Novel Functional Renal PET Imaging with 18F-FDS in Human Subjects. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2019, 44, 410–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissinger, M.; Seyfried, K.C.; Ursprung, S.; Castaneda-Vega, S.; Seith, F.; von Beschwitz, S.; Vogel, J.; Ghibes, P.; Nikolaou, K.; la Fougère, C.; et al. Non-Invasive Estimation of Split Renal Function from Routine 68Ga-SSR-PET/CT Scans. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1169451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conen, P.; Pennetta, F.; Dendl, K.; Hertel, F.; Vogg, A.; Haberkorn, U.; Giesel, F.L.; Mottaghy, F.M. [68 Ga]Ga-FAPI Uptake Correlates with the State of Chronic Kidney Disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 3365–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gühne, F.; Schilder, T.; Seifert, P.; Kühnel, C.; Freesmeyer, M. Dependence of Renal Uptake on Kidney Function in [68Ga]Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT Imaging. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibeau-Delisle, A.; Bouabdallaoui, N.; Lamarche, C.; Harel, F.; Pelletier-Galarneau, M. Assessment of Renal Perfusion with 82-Rubidium PET in Patients with Normal and Abnormal Renal Function. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2024, 45, 958–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaewput, C.; Vinjamuri, S. Comparison of Renal Uptake of 68Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT and Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate before and after Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy in Patients with Metastatic Neuroendocrine Tumours. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2016, 37, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanoudaki, V.C.; Ziegler, S.I. PET & SPECT Instrumentation. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulska, M.; Falborg, L. A Simple Kit for the Good-Manufacturing-Practice Production of [68Ga]Ga-EDTA. Molecules 2023, 28, 6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, R.A.; Pomper, M.G.; Buck, A.K.; Rowe, S.P.; Higuchi, T. SPECT and PET Radiotracers in Renal Imaging. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2022, 52, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crișan, G.; Moldovean-Cioroianu, N.S.; Timaru, D.-G.; Andrieș, G.; Căinap, C.; Chiș, V. Radiopharmaceuticals for PET and SPECT Imaging: A Literature Review over the Last Decade. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaping, L. The Study on the Effectiveness of [68Ga]Ga-HBED-CC-DiAsp PET/CT in Calculating Glomerular Filtration Rate and Predicting Residual Renal Function After Partial Nephrectomy. 2025. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06973798 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

| Authors | year | Month | Location | Type of Study | Sample Size | Reference Standard Used in GFR Measurement | PET Radiotracer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hofman et al. [21] | 2015 | 3 | Australia | Original/Prospective | 25 | Plasma clearance of 51Cr-EDTA (68Ga-EDTA was the experimental tracer). | 68Ga-EDTA |

| Kaewput et al. [27] | 2016 | 12 | Thailand | Original/Retrospective Observational | 32 | Estimated GFR (eGFR) Cockcroft-Gault formula (adjusted for body surface area), derived from serum creatinine. | 68Ga-DOTANOC |

| Geist et al. [17] | 2018 | 5 | Austria | Original/Prospective | 24 | eGFR using the CKD-EPI formula, derived from serum creatinine. | 18F-FDG |

| Werner et al. [22] | 2019 | 5 | Germany | Human Pilot/First-in-Human | 2 | No reference GFR standard reported (feasibility study) | 18F-FDS |

| Zhou et al. [19] | 2021 | 2 | China | Original/Diagnostic Accuracy Prospective | 13 | eGFR (CKD-EPI), derived from serum creatinine. Renal biopsy was the reference for fibrosis, not GFR. | 68Ga-FAPI-04 |

| Kersting et al. [20] | 2022 | 8 | Germany | Original/Diagnostic Accuracy Prospective | 12 | eGFR (CKD-EPI), derived from serum creatinine. | 68Ga-DOTA |

| Conen et al. [24] | 2022 | 8 | Germany | Original/Retrospective | 81 | Tubular extraction rate (TER) from 99ᵐTc-MAG3 scintigraphy and eGFR (CKD-EPI). | 68Ga-FAPI, 68Ga-PSMA and 68Ga-DOTATOC |

| Weissinger et al. [23] | 2023 | 6 | Germany | Original/Diagnostic Accuracy Retrospective | 25 | Reference standard tubular extraction rate (TER-MAG) from 99mTc-MAG3 scintigraphy and GFR CKD-EPI formula from serum creatinine. | 68Ga-ha DOTATATE |

| Nishikawa et al. [18] | 2023 | 1 | Japan | Original/Prospective | 15 | Estimated Renal Blood Flow (eRBF) calculated from eGFR (CKD-EPI formula). | 64Cu-ATSM |

| Guhne et al. [25] | 2024 | 3 | Germany | Original/Retrospective Observational | 103 | eRBF calculated from eGFR (CKD-EPI formula). | 68Ga-PSMA-11 |

| Bibeau-Delisle et al. [26] | 2024 | 11 | Canada | Original/Retrospective Observational | 51 | eGFR (CKD-EPI), derived from serum creatinine. | 82Rb-RbCl |

| Radiotracer | Radioisotope Label | Key Characteristics | Main Clinical/Research Findings | Advantages | Limitations/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 68Ga-EDTA | Gallium-68 | Stable metal chelate, low protein binding, exclusive glomerular filtration | Strong correlation with reference 51Cr-EDTA clearance (r = 0.94), suitable for split renal function assessment | High spatial/temporal resolution, 3D quantification, low radiation dose | Underestimates GFR >150 mL/min, scarce large prospective validation |

| 68Ga-DOTANOC | Gallium-68 | Somatostatin receptor targeting | Weak correlation with eGFR; uptake increased post peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) | Potential early biomarker for renal toxicity post-PRRT | Limited correlation with GFR, retrospective studies |

| 18F-FDG | Fluorine-18 | Widely available PET tracer, not renal specific | Dynamic PET/MRI showed correlation with GFR (r = 0.88), effective renal plasma flow estimation | Dual-purpose oncologic and renal function imaging | Indirect reference method, limited in renal pathology |

| 18F-FDS | Fluorine-18 | Structural similarity to inulin, low protein binding | Pilot study: favorable renal kinetics, potential GFR tracer, sorbitol-to-inulin clearance 1.01 | Compatible with existing PET infrastructure, lower radiation | Very limited clinical data, small sample size |

| 68Ga-PSMA-11 | Gallium-68 | Prostate-specific membrane antigen targeting | Moderate correlation of renal cortex volume with eGFR; SUV measures not correlating | Quantifies renal cortex volume with good anatomical detail | Not reliable for direct GFR measurement |

| 68Ga-FAPI-04 | Gallium-68 | Targets fibroblast activation protein in fibrosis | Uptake correlates with renal fibrosis severity, SUVmax increases with fibrosis grade | Non-invasive fibrosis imaging, potential complement to functional GFR | Needs validation against biopsy, limited clinical data |

| 64Cu-ATSM | Copper-64 | PET/MRI for renal blood flow quantification | Strong correlation with ASL-MRI and estimated RBF, differentiates CKD from healthy controls | First validated PET method for spatial RBF; dual modality | Small sample size, still indirect for GFR |

| 68Ga-DOTA | Gallium-68 | Small-molecule filtration agent used in dynamic imaging. | Good correlation with serum creatinine-derived GFR; shorter scan protocols feasible | Enables dynamic renal function and anatomical imaging | Reliant on surrogate reference GFR methods |

| 68Ga-ha DOTATATE | Gallium-68 | Somatostatin receptor targeting | Moderate correlation of novel PET metrics with GFR; potential for split renal function assessment | Possible non-invasive GFR estimation from routine PET scans | Retrospective, indirect GFR references |

| 82Rb-RbCl | Rubidium-82 | Primary use in myocardial perfusion imaging; investigational for renal blood flow assessment | Correlation of RBF and eGFR demonstrated | Non-invasive renal perfusion assessment | Does not directly measure GFR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdulrahman, M.; Abdlkadir, A.S.; Moghrabi, S.; Alyazjeen, S.; Al-Qasem, S.; Sweedat, D.A.S.; Ruzzeh, S.; Stanimirović, D.; Kreissl, M.C.; Shi, H.; et al. Advancements in Renal Imaging: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of PET Probes for Enhanced GFR and Renal Perfusion Assessment. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3209. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243209

Abdulrahman M, Abdlkadir AS, Moghrabi S, Alyazjeen S, Al-Qasem S, Sweedat DAS, Ruzzeh S, Stanimirović D, Kreissl MC, Shi H, et al. Advancements in Renal Imaging: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of PET Probes for Enhanced GFR and Renal Perfusion Assessment. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3209. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243209

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdulrahman, Marwah, Ahmed Saad Abdlkadir, Serin Moghrabi, Salem Alyazjeen, Soud Al-Qasem, Deya’ Aldeen Sulaiman Sweedat, Saad Ruzzeh, Dragi Stanimirović, Michael C. Kreissl, Hongcheng Shi, and et al. 2025. "Advancements in Renal Imaging: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of PET Probes for Enhanced GFR and Renal Perfusion Assessment" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3209. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243209

APA StyleAbdulrahman, M., Abdlkadir, A. S., Moghrabi, S., Alyazjeen, S., Al-Qasem, S., Sweedat, D. A. S., Ruzzeh, S., Stanimirović, D., Kreissl, M. C., Shi, H., Sathekge, M., & Al-Ibraheem, A. (2025). Advancements in Renal Imaging: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of PET Probes for Enhanced GFR and Renal Perfusion Assessment. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3209. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243209