Clinical Symptom Resolution Following PCR-Guided vs. Culture and Susceptibility-Guided Management of Complicated UTI: How Time-To-Antibiotic Start and Antibiotic Appropriateness Mediate the Benefit of Multiplex PCR—An Ad Hoc Analysis of NCT06996301

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethics

2.2. Analytic Cohorts and Sample Selection

- Descriptive and per-symptom analyses (symptoms resolution): the end-of-study (EOS) population, including all participants with completed clinical follow-up (28 days) and paired PCR+ culture results (N = 362; PCR arm n = 193, C&S arm n = 169). Discordant EOS specimens (PCR+/C− and PCR−/C+) were analyzed as a nested subgroup (N = 116; PCR+/C− = 102; PCR−/C+ = 14).

- Multivariable prediction and causal mediation analyses: the end-of-study (EOS) population, including all participants with completed clinical follow-up (28 days) and paired PCR + culture results (N = 362; PCR arm n = 193, C&S arm n = 169).

2.3. Data Sources and Variables

- Outcome variables

- ∘

- Complete clinical cure (primary outcome, binary): absence of all baseline symptoms recorded at the prespecified EOS visit.

- ∘

- Partial cure (secondary, binary): ≥50% reduction in number of baseline symptoms at EOS.

- ∘

- Per-symptom presence/absence at enrollment and EOS (dysuria/frequency/urgency/hematuria, suprapubic/pelvic pain, costovertebral angle [CVA] tenderness, fever, nausea/vomiting, leukocyturia/pyuria).

- ∘

- Microbiologic eradication at EOS: absence of baseline pathogen (culture−) in the C&S Arm and (PCR−) in the PCR Arm.

- Exposure/predictors/covariates

- ∘

- Randomized diagnostic arm (PCR vs. C&S).

- ∘

- Time-to-antibiotic start (time_to_abx_h; hours): defined as the interval from urine collection to administration of the first antibiotic prescribed based on the assigned diagnostic results. Note: Empiric antibiotics administered at the baseline visit in the culture arm (per standard-of-care practice) were not included in this calculation. time_to_abx_h was used as both predictor and mediator. For mediation, we used the log-transform to stabilize skew:

- ∘

- Antibiotic appropriateness (binary variable: Yes/No): Antibiotic appropriateness (binary variable: Yes/No): assessed by the treating investigator at end-of-study (EOS), once diagnostic blinding was lifted, and used as both predictor and mediator. Appropriateness was defined by comparing the antibiotic prescribed (based on the assigned diagnostic) with (a) the complete pathogen and resistance profile detected by both diagnostics and (b) antimicrobial treatment guidelines.

- -

- Appropriate (Yes): the prescribed antibiotic, based on assigned diagnostic arm results, provided adequate coverage for all uropathogens and resistance markers and did not omit any organism or marker detected by the comparator test.

- -

- Inappropriate (No): the prescribed antibiotic failed to cover one or more organisms or resistance markers detected by the comparator test.

- ∘

- Baseline symptom count (2, 3, or 4).

- ∘

- Mono- vs. polymicrobial infection (culture/PCR concordance flag).

- ∘

- Age category (≥65 vs. <65 years), sex at birth (male/female), presence of comorbidity (metabolic disease, immunosuppression, CKD), recurrent UTI status (≥3 UTI episodes in prior 12 months), and failure of first-line therapy before enrollment.

2.4. Derived Variables and Outcome Classification

- Antibiotic appropriateness:

- -

- Appropriate: if the investigator selected Agree or Strongly agree.

- -

- Inappropriate: if the investigator selected Neutral, Disagree, or Strongly disagree.

- Percent symptoms change for each symptom category ():

- Symptom-change categories: subject-level change collapsed into clinically interpretable bins:

- ∘

- Clinical failure: no symptom reduction or addition of symptoms (0 symptom reduction or ≥1 additional symptom).

- ∘

- Favorable clinical outcome (FCO): ≥1 symptom reduction, further subdivided into 1, 2, 3, or 4 symptom reductions.

- Discordant specimen definitions:

- ∘

- PCR+/C−: PCR detects a pathogen at baseline, whereas culture is negative for that pathogen.

- ∘

- PCR−/C+: culture detects organism at baseline not detected by PCR.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Descriptive statistics and per-symptom testing

- Multivariable prediction model (logistic mixed effects)

- ∘

- = 1 if randomized to PCR-guided management, 0 if C&S-guided;

- ∘

- , natural-log transform of hours from specimen collection to first antibiotic (stabilizes skew);

- ∘

- = 1 if culture negative at EOS (microbiologic eradication), 0 otherwise;

- ∘

- = 1 if first prescribed antibiotic was adjudicated appropriate (Yes) at EOS, 0 if inappropriate;

- ∘

- = baseline covariates: age category (≥65 vs. <65), sex at birth, presence of comorbidity (metabolic disease/immunosuppression/CKD), recurrent UTI (≥3 prior episodes), failure of first-line therapy before enrollment, baseline symptom count (2, 3, or 4), infection type (mono vs. poly);

- ∘

- is a site random intercept.

- ∘

- Model T (Total-effect): estimate the total effect of randomized assignment (Arm) on clinical cure. This model did not include post-randomization mediators (log_time, Appropriate) when presenting the total effect. Model T, therefore, includes Arm and the baseline covariates plus site random intercept.

- ∘

- Model M1 (time mediation check): included log_time (mediator) with baseline covariates, quantified attenuation of the Arm coefficient when adjusting for time.

- ∘

- Model M2 (mechanistic model): includes both mediators log_time and Appropriate plus baseline covariates, used to show associations conditional on mediators and to construct mediation decomposition.

- Causal mediation analysis (decomposition of indirect effects)

- Parallel mediation (time and appropriateness as independent mediators): estimate the separate indirect effects of Arm → time → cure and Arm → appropriateness → cure, and the combined indirect effect.

- Sequential mediation (time upstream of appropriateness): appropriate when earlier availability of results plausibly increases the probability of prescribing an appropriate antibiotic (Arm → time → appropriateness → cure). In this specification we model appropriateness as potentially dependent on log_time.

- ∘

- Model T provides the total effect (policy-relevant).

- ∘

- Mechanistic models and ACME/ADE components decompose the total effect and are conditional on stronger assumptions (sequential ignorability). We present both to be transparent.

- Exploratory Analysis: Partial Cure

- Discordant subgroup analyses

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Per-Symptom Changes from Baseline to EOS

- Lower urinary tract symptoms (dysuria/frequency/urgency/hematuria): PCR enrollment → EOS 154 → 8 (−94.8%) vs. C&S 132 → 19 (−85.6%); p = 0.005 (PCR superior).

- Leukocyturia (pyuria): PCR 160 → 20 (−87.5%) vs. C&S 140 → 30 (−78.6%); p = 0.042 (PCR superior).

3.3. Symptom-Change Categories and Clinical Failure vs. Favorable Clinical Outcome

- Clinical failure subtotal (no improvement or symptom addition) occurred in 23/193 (11.9%) of PCR patients vs. 37/169 (21.9%) of C&S patients (p = 0.011), indicating a lower failure rate with PCR. This reduction in failure was driven by fewer participants with symptom addition: two-symptom and one-symptom worsening were more frequent in the C&S arm (combined worse categories 6.6% C&S vs. 1.5% PCR; Fisher p ≈ 0.028 and p ≈ 0.018 for the two subcategories).

- Favorable clinical outcome (≥1 symptom reduction) occurred in 170/193 (88.1%) PCR vs. 132/169 (78.1%) C&S (complement of failure; p = 0.011).

- Magnitude of improvement also favored PCR: two-symptom reductions were observed in 66/193 (34.2%) PCR vs. 42/169 (24.8%) C&S (p = 0.0311), and three-symptom reductions were 23/193 (11.9%) vs. 11/169 (6.3%) (p = 0.047). One-symptom reduction frequency did not differ significantly by arm (PCR 40.9% vs. C&S 45.5%; p = 0.547).

3.4. Mediators Description: Time-to-Antibiotic and Antibiotic Appropriateness

3.5. Summary of Cure Metrics

- Complete clinical cure (no baseline symptoms at EOS): PCR 143/193 (74.1%) vs. C&S 106/169 (62.7%); p = 0.020.

- Partial cure (≥50% symptom reduction): PCR 159/193 (82.4%) vs. C&S 121/169 (71.6%); p = 0.014.

- Clinical cure with microbiologic eradication (both clinical and culture): PCR 120/193 (62.2%) vs. C&S 95/169 (56.2%); difference not statistically significant (p = 0.249).

- Clinical cure without microbiologic eradication (clinical cure but persistent culture positivity) occurred more often in the PCR arm (23/193, 11.9%) than in the C&S arm (11/169, 6.5%; p = 0.078); this pattern highlights imperfect concordance between symptom resolution and culture status and suggests that clinical improvement can occur despite persistent culture positivity in a minority of cases.

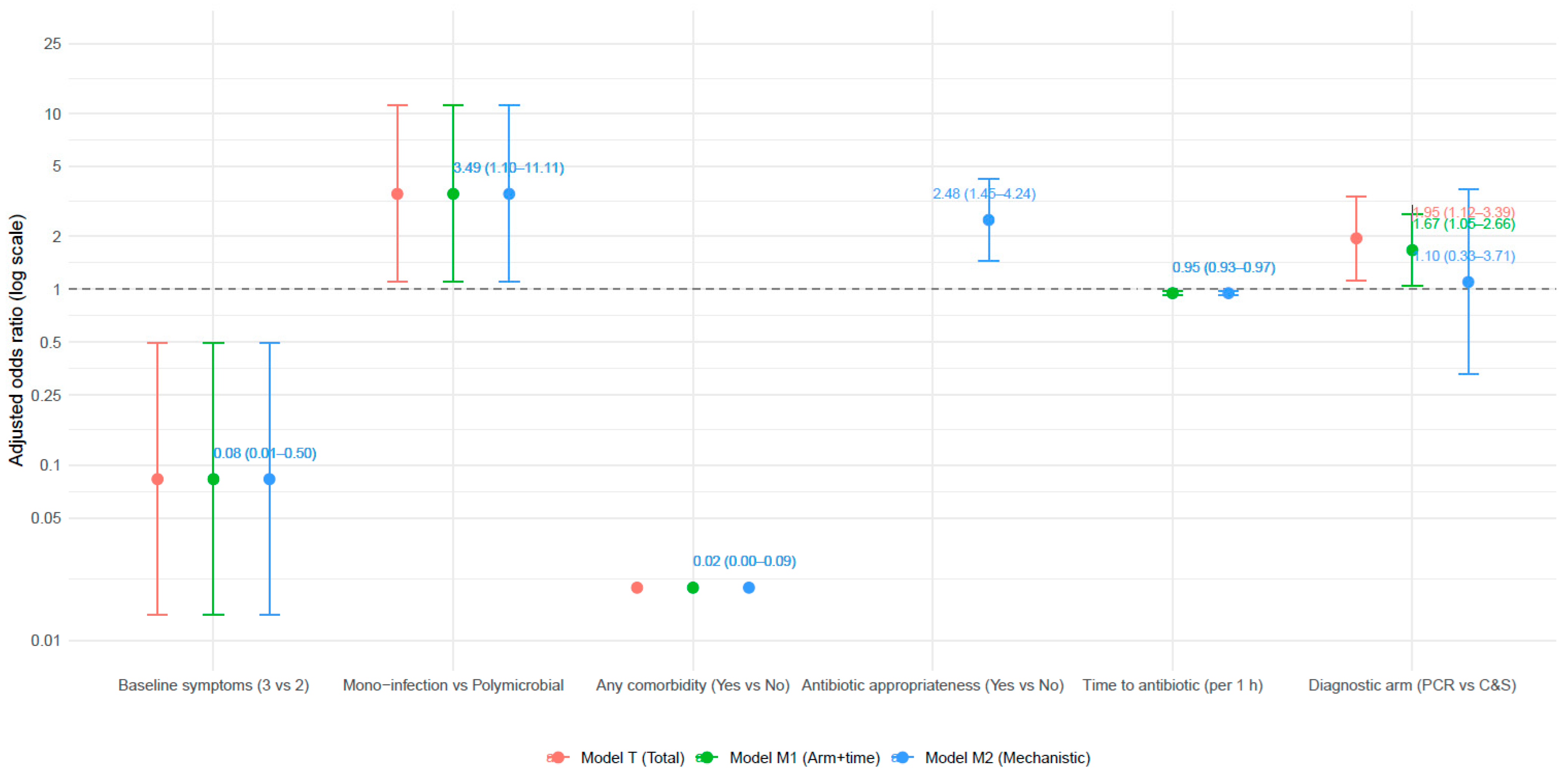

3.6. Multivariable Predictors of Complete Clinical Cure

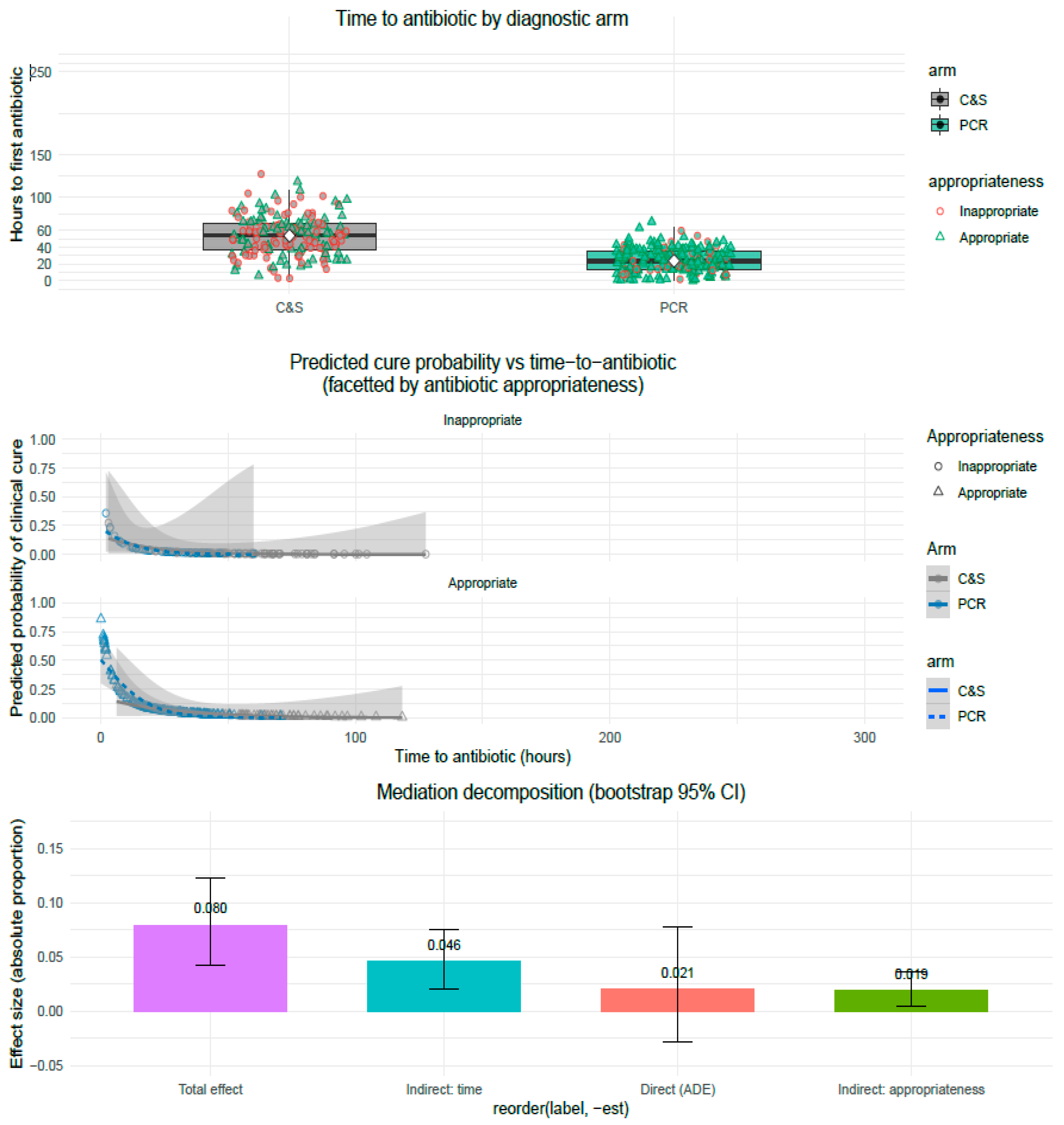

3.7. Causal Mediation Analysis: Decomposition of Indirect Effects

- Mediator models

- Outcome model (cure)

- Mediation estimates: parallel decomposition

- ∘

- ACME: total indirect effect (combined mediators: time + appropriateness): 0.0648 (95% CI 0.0343 to 0.0977). This is the fraction (absolute proportion) of the probability difference in cure conveyed via the mediators. The CI excludes zero, indicating a statistically significant indirect effect.

- ∘

- ADE: average direct effect (PCR → cure not via the modeled mediators): 0.0207 (95% CI: 0.0282 to 0.0784). The ADE is small and its CI overlaps zero, indicating the residual direct effect is not statistically significant after accounting for mediators.

- ∘

- Total effect (ACME + ADE): 0.0796 (95% CI 0.0419 to 0.1225), statistically significant overall improvement in cure probability for PCR vs. C&S.

- ∘

- Proportion mediated (ACME/Total): ≈74%. In other words, ~ three-quarters of the total benefit attributable to PCR can be explained by the modeled mediators.

- ACME_time (Arm → time → cure): 0.0460 (95% CI 0.0210 to 0.0760).

- ACME_appropriateness (Arm → appropriateness → cure): 0.0188 (95% CI 0.0050 to 0.0360).

- Sequential mediation (time upstream of appropriateness)

- Interpretation

3.8. Exploratory Analysis: Partial Cure

- Multivariable Models: Partial Cure (Figure 4)

- Mediation Analysis: Partial Cure (Figure 4)

3.9. Discordant Subgroup Findings and Sensitivity Analyses

- PCR+/C− participants tended to have intermediate clinical cure rates (complete cure 59.8% PCR+/C−) that were higher than PCR−/C+ (35.7%) but lower than the overall PCR arm. These discordant comparisons are, however, underpowered, and Fisher p-values were generally nonsignificant or imprecise.

- The existence of PCR+/C− clinical cures supports the clinical relevance of PCR-detected organisms even when culture is negative (consistent with culture loss due to delays or fastidious organisms), but prospective evaluation and adjudication would be needed to confirm causality.

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

- Complete clinical cure (no baseline symptoms at EOS) occurred in 74.1% of PCR patients versus 62.7% of C&S patients (p = 0.020).

- Partial cure (≥50% symptom reduction) occurred in 82.4% versus 71.6% (p = 0.014).

- Per-symptom reductions were consistently larger in the PCR arm; statistically significant advantages were observed for lower urinary tract symptoms (dysuria/frequency/urgency/hematuria; −94.8% vs. −85.6%; p = 0.005) and leukocyturia (−87.5% vs. −78.6%; p = 0.042).

- The median time from specimen collection to first antibiotic was substantially shorter in the PCR arm (20 h, IQR 12–36) compared with C&S (52 h, IQR 30–66) (p < 0.001).

- Antibiotic appropriateness (adjudicated at EOS) was higher in the PCR arm (82.4%) than C&S (62.1%) (p < 0.001).

- Even though empiric antibiotics were permitted and frequently initiated at the baseline visit in the C&S arm (as is standard of care) the overall clinical outcomes in the C&S group did not surpass those of the PCR group. This indicates that faster, organism-specific results from PCR provided a meaningful clinical advantage beyond empiric therapy alone.

4.2. How Do the Data Support Mechanism (Timeliness First, Content Second)

4.2.1. Timeliness Is the Dominant Pathway

- ∘

- The large randomized difference in median time-to-antibiotic (20 h vs. 52 h) is the foundational process change produced by randomization to PCR.

- ∘

- Time-to-antibiotic was a strong, independent predictor in regression (adjusted OR per 1 h delay ≈ 0.95, 95% CI 0.926–0.975; p < 0.001), so even modest hour-level delays translate to clinically meaningful reductions in odds of cure across the observed range.

- ∘

- Mediation decomposition attributes the majority of the mediated effect to the time pathway (ACME_time ≈ 0.046 of the 0.0648 total indirect effect). These results are consistent with earlier randomized and quasi-randomized work in bloodstream infections showing that rapid identification improves outcomes primarily when operationalized into earlier appropriate therapy [10,11,12,13].

4.2.2. Antibiotic Appropriateness Is a Complementary Mediator

4.2.3. Residual Direct Diagnostic Effects Are Small

4.3. Exploratory Analysis: Partial Cure

4.4. Discordant Specimens and Clinical Relevance

- PCR+/C− patients achieved a complete clinical cure rate of 59.8%, compared with 35.7% in PCR−/C+ patients (numbers small, limited precision).

- These patterns suggest that many PCR detections that lack culture confirmation represent clinically relevant findings, such as fastidious, low-burden, or transport-sensitive organisms that molecular platforms can detect reliably even when culture recovery fails.

- Recent peer-reviewed evaluations of multiplex urine PCR platforms further reinforce this interpretation. Several well-controlled studies have demonstrated that Ct/Cq or ΔCt values align closely with culture-derived CFU levels, supporting the biological plausibility of semi-quantitative interpretation [19,20]. These studies also show that specimen collection method (clean-catch vs. catheter) does not materially change Ct/CFU calibration when consistent workflows are used—mirroring our findings that collection technique did not influence ΔCt–CFU relationships [19,20].

- Complementary work on genotype–phenotype agreement in urinary pathogens [21] demonstrates high concordance for major resistance determinants, reinforcing that multiplex PCR results, when interpreted with stewardship oversight, provide clinically actionable information rather than noise. However, these quantitative associations were modest and the reported ROC discrimination was only moderate, underscoring that ΔCt should be viewed as an adjunctive confidence metric that complements (rather than replaces) phenotypic AST.

- Collectively [19,20,21], these external data support the view that molecular detection is not merely more “sensitive,” but more complete, particularly for organisms commonly under-recovered by standard culture. Acting on those molecular findings (when contextualized with symptoms and stewardship guidance) can therefore produce meaningful symptom improvement. Nonetheless, careful review remains essential to avoid overtreatment of contaminants or clinically insignificant detections.

4.5. Clinical and Stewardship Implications

4.6. Heteroresistance, Polymicrobial Infections, and the Limits of Culture

4.7. Strengths and Limitations

- Randomized parent trial and paired testing on all participants support causal inference about Arm → time differences and allow rigorous linkage of diagnostics → prescribing → clinical outcomes.

- Prospectively collected time-to-antibiotic data enabled a well-powered mediation decomposition.

- Use of mixed-effects models and nonparametric bootstrap mediation inference increases robustness to clustering and distributional assumptions.

- Nonrandom mediator assignment. Time and appropriateness were not randomized; mediation estimates assume no unmeasured mediator–outcome confounding conditional on covariates.

- Appropriateness measurement. Appropriateness was adjudicated at EOS using combined diagnostic information and guideline reference, a pragmatic but imperfect measure that may incorporate circularity (treatment judged against the combined data). We mitigated bias by prespecifying adjudication rules and using sensitivity analyses.

- Discordant subgroup sample size. Small numbers in PCR−/C+ cells limit precision for subgroup comparisons.

- External validity. The trial population (older adults at six U.S. sites) may limit generalizability to different outpatient or younger populations and health systems with different turnaround logistics.

- Definition of time-to-antibiotic. In this study, time-to-antibiotic was defined as the interval from urine collection to the first diagnosis-guided antibiotic decision, rather than to the empiric antibiotic administered at baseline in the culture arm only. This differs from real-world practice, where empiric therapy is typically initiated immediately for all patients with suspected cUTI. Importantly, the PCR arm did not receive empiric therapy at baseline, whereas the culture arm did, an asymmetry that inherently favors the culture arm. Because empiric therapy begins at time zero for the culture-guided group, this definition creates a conservative comparison that reduces the apparent benefit of PCR. Despite this advantage, the PCR arm still demonstrated significantly better clinical outcomes. Thus, the mediation findings indicate that the PCR benefit is not an artifact of the timing definition but reflects genuine acceleration of targeted therapy once PCR results became available.

4.8. Implications for Future Research

- Implementation trials that randomize rapid result delivery plus stewardship action (versus standard reporting) would test whether changing the response pathway further amplifies benefit.

- Cost-effectiveness and long-term outcomes (recurrence, resistance selection) should be measured to fully characterize value.

- Diagnostic strategy optimization: parallel PCR + C&S workflows, interpretive reporting, and stewardship algorithms deserve prospective evaluation to define best practice and minimize unintended harms (over-treatment). Real-world evidence suggests such integrated approaches reduce severity and cost in complicated or recurrent UTI cohorts.

- Molecular quantitation and heteroresistance: studies that combine quantitative PCR metrics with single-cell methods or pooled phenotypic susceptibility testing may refine prediction of clinical failure and guide de-escalation strategies.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Baimakhanova, B.; Sadanov, A.; Berezin, V.; Baimakhanova, G.; Trenozhnikova, L.; Orasymbet, S.; Seitimova, G.; Kalmakhanov, S.; Xetayeva, G.; Shynykul, Z.; et al. Emerging Technologies for the Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infections: Advances in Molecular Detection and Resistance Profiling. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A.S.; Rao, S.N. Syndromic testing for the diagnosis of infectious diseases: The right test if used for the right patient. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76 (Suppl. S3), iii2–iii3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serapide, F.; Pallone, R.; Quirino, A.; Marascio, N.; Barreca, G.S.; Davoli, C.; Lionello, R.; Matera, G.; Russo, A. Impact of Multiplex PCR on Diagnosis of Bacterial and Fungal Infections and Choice of Appropriate Antimicrobial Therapy. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.; Baunoch, D. Comparison shows that multiplex polymerase chain reaction identifies infection-associated urinary biomarker–positive urinary tract infections that are missed by standard urine culture. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2023, 58, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardjadj, M. Advances in Point-of-Care Infectious Disease Diagnostics: Integration of Technologies, Validation, Artificial Intelligence, and Regulatory Oversight. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo, X.G.; Arcila, K.V.O.; Riascos, S.H.M.; García-Perdomo, H.A. Accuracy of molecular diagnostic techniques in patients with a confirmed urine culture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2022, 16, E484–E489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardjadj, M.; Chang, T.W.; Chavez, R.; Derrick, D.; Spangler, F.L.; Priestly, I.P.; Park, L.Y.; Huard, T.K. The clinical validity and utility of PCR compared to conventional culture and sensitivity testing for the management of complicated urinary tract infections in adults: A secondary (ad hoc) analysis of pathogen detection, resistance profiles, and impact on clinical outcomes. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangler, F.L.; Williams, C.; Aberger, M.E.; Wilson, B.A.; Ajib, K.; Gholami, S.S.; Goodwin, H.N.; Park, L.Y.; Kardjadj, M.; Derrick, D.; et al. Clinical utility of PCR compared to conventional culture and sensitivity testing for the management of complicated urinary tract infections in adults: Part I: Assessment of clinical outcomes, investigator satisfaction scores, and turnaround times. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2025, 111, 116601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangler, F.L.; Williams, C.; Aberger, M.E.; Wilson, B.A.; Ajib, K.; Gholami, S.S.; Goodwin, H.N.; Park, L.Y.; Kardjadj, M.; Derrick, D.; et al. Clinical utility of PCR compared to conventional culture and sensitivity testing for management of complicated urinary tract infections in adults: Part II: Evaluation of diagnostic concordance, discordant results, and anti- microbial selection efficacy. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2025, 111, 116646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Teng, C.B.; Cunningham, S.A.; Ihde, S.M.; Steckelberg, J.M.; Moriarty, J.P.; Shah, N.D.; Mandrekar, J.N.; Patel, R.R. Trial of Rapid Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction-Based Blood Culture Identification and Susceptibility Testing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacVane, S.H.; Nolte, F.S. Benefits of Adding a Rapid PCR-Based Blood Culture Identification Panel to an Established Antimicrobial Stewardship Program. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 2455–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasef, R.; El Lababidi, R.; Alatoom, A.; Krishnaprasad, S.; Bonilla, F. The Impact of Integrating Rapid PCR-Based Blood Culture Identification Panel to an Established Antimicrobial Stewardship Program in the United Arab of Emirates. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 91, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timbrook, T.T.; Morton, J.B.; McConeghy, K.W.; Caffrey, A.R.; Mylonakis, E.; LaPlante, K.L. The Effect of Molecular Rapid Diagnostic Testing on Clinical Outcomes in Bloodstream Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 64, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatfield, K.M.; Kabbani, S.; See, I.; Currie, D.W.; Kim, C.; Jacobs Slifka, K.; Magill, S.S.; Hicks, L.A.; McDonald, L.C.; Jernigan, J.; et al. Use of Multiplex Molecular Panels to Diagnose Urinary Tract Infection in Older Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2446842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messacar, K.; Parker, S.K.; Todd, J.K.; Dominguez, S.R. Implementation of rapid molecular infectious disease diagnostics: The role of antimicrobial stewardship. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 64, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, R.E.; Al-Haboubi, M.; Petticrew, M.P.; Eastmure, E.; Peacock, S.J.; Mays, N. Sankey diagrams can clarify ‘evidence attrition’: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of rapid diagnostic tests for antimicrobial resistance. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 144, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J. Explanation in Causal Inference: Methods for Mediation and Interaction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Schubert, M.; Liao, J. Causal mediation analysis in the context of clinical research. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardjadj, M.; Priestly, I.P.; Chavez, R.; Derrick, D.; Huard, T.K. Semi-Quantitative ΔCt Thresholds for Bacteriuria and Pre-Analytic Drivers of PCR-Culture Discordance in Complicated UTI: An Analysis of NCT06996301. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, P.; Vallabhaneni, A.; Ager, E.; Alexander, B.; Rosato, A.; Singh, V. Clinical Relevance of PCR Versus Culture in Urinary Tract Infections Diagnosis: Quantification Cycle as a Predictor of Bacterial Load. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardjadj, M.; Priestly, I.P.; Chavez, R.; Derrick, D.; Huard, T.K. Genotype–Phenotype Concordance and Ct-Informed Predictive Rules for Antimicrobial Resistance in Adult Patients with Complicated Urinary Tract Infections: Clinical and Stewardship Implications from the NCT06996301 Trial. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korman, H.J.; Baunoch, D.; Luke, N.; Wang, D.; Zhao, X.; Levin, M.; Wenzler, D.L.; Mathur, M. A diagnostic test combining molecular testing with phenotypic pooled antibiotic susceptibility improved the clinical outcomes of patients with non-E. coli or polymicrobial complicated urinary tract infections. Res. Rep. Urol. 2023, 15, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, J.; Hafron, J.; Holton, M.; Ervin, C.; Hollander, M.B.; Kapoor, D.A. The impact of polymerase chain reaction urine testing on clinical decision-making in the management of complex urinary tract infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.S.C.; Lukacz, E.S.; Juster, I.A.; Niecko, T.; Ashok, A.; Vollstedt, A.J.; Baunoch, D.; Mathur, M. Real-world evidence that a novel diagnostic combining molecular testing with pooled antibiotic susceptibility testing is associated with reduced infection severity and lower cost compared with standard urine culture in patients with complicated or persistently recurrent urinary tract infections. JU Open Plus. 2023, 1, e00021. [Google Scholar]

- Kardjadj, M. Clinical Utility of PCR in Complicated Urinary Tract Infections: A Paradigm Shift in Diagnostics and Management. JU Open Plus 2025, 3, e00114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, Z.R.; Rad, Z.R.; Goudarzi, H.; Goudarzi, M.; Pourdehghan, P.; Kargar, M.; Shams, S.; Hashemi, A. Detection of colistin heteroresistance in carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates in Iran. Int. J. Microbiol. 2025, 2025, 5571153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardjadj, M. Regulatory Approved Point-of-Care Diagnostics (FDA & Health Canada): A Comprehensive Framework for Analytical Validity, Clinical Validity, and Clinical Utility in Medical Devices. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2025, 10, 1622–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mod ITT Pop at EOS (N = 362) | p | Discordant Result Pop at EOS (N = 116) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Arm (n, %) | C&S Arm (n, %) | PCR+ and CS− (n, %) | PCR− and CS+ (n, %) | ||||

| Age | 65 yrs | 174 (90.2%) | 152 (89.9%) | p = 0.946 | 83 (81.4%) | 13 (92.9%) | p ≈ 0.493 |

| <65 yrs | 19 (9.8%) | 17 (10.1%) | 19 (18.6%) | 1 (7.1%) | |||

| Sex at birth | Male | 53 (27.5%) | 50 (29.6%) | p = 0.630 | 24 (23.5%) | 3 (21.4%) | p ≈ 1.000 |

| Female | 140 (72.5%) | 119 (70.4%) | 78 (76.5%) | 11 (78.6%) | |||

| Underlying comorbidity * | Yes | 105 (54.4%) | 91 (53.8%) | p = 0.893 | 61 (59.8%) | 9 (64.3%) | p ≈ 1.000 |

| No | 88 (45.6%) | 78 (46.2%) | 41 (40.2%) | 5 (35.7%) | |||

| Recurrent UTI (rUTI) ** | Yes | 113 (58.6%) | 95 (56.2%) | p = 0.610 | 58 (56.9%) | 8 (57.1%) | p ≈ 1.000 |

| No | 80 (41.4%) | 74 (43.8%) | 44 (43.1%) | 6 (42.9%) | |||

| Active UTI failed 1st-line | Yes | 87 (45.1%) | 92 (54.4%) | p = 0.081 | 49 (48.0%) | 5 (35.7%) | p ≈ 0.524 |

| No | 106 (54.9%) | 77 (45.6%) | 53 (52.0%) | 9 (64.3%) | |||

| cUTI Symptoms’ association | 02 symptoms | 166 (86.0%) | 144 (85.2%) | p = 0.828 | 87 (85.3%) | 13 (92.9%) | p ≈ 0.683 |

| 03 symptoms | 24 (12.4%) | 22 (13.0%) | 12 (11.8%) | 1 (7.1%) | |||

| 04 symptoms | 3 (1.6%) | 3 (1.8%) | 3 (2.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| cUTI Event | Mono-infection | 109 (56.5%) | 115 (68.0%) | p = 0.019 | 59 (57.8%) | 12 (85.7%) | p ≈ 0.074 |

| Poly-infection | 84 (43.5%) | 54 (32.0%) | 43 (42.2%) | 2 (14.3%) | |||

| Total | 193 | 169 | — | 102 | 14 | — | |

| Symptom | Mod ITT Pop at EOS (N = 362) | Discordant Result Pop at EOS Visit (N = 116) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Arm Enrollment/EOS (n) | % Change (PCR) | C&S Arm Enrollment/EOS (n) | % Change (C&S) | p | PCR+/C− Enr/EOS (n) | % Change (PCR+/C−) | PCR−/C+ Enr/EOS (n) | % Change (PCR−/C+) | p | |

| Fever | 20/2 | −90.0% | 18/5 | −72.2% | p = 0.185 | 8/1 | −87.5% | 2/0 | −100% | p ≈ 1.000 |

| Dysuria/frequency/urgency/hematuria | 154/8 | −94.8% | 132/19 | −85.6% | p = 0.005 | 80/18 | −77.5% | 12/4 | −66.7% | p ≈ 0.327 |

| Suprapubic/pelvic pain | 42/2 | −95.2% | 38/6 | −84.2% | p = 0.104 | 20/3 | −85.0% | 3/1 | −66.7% | p ≈ 1.000 |

| CVA tenderness | 25/3 | −88.0% | 22/4 | −81.8% | p = 0.572 | 12/4 | −66.7% | 1/1 | 0% | p ≈ 0.333 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 12/1 | −91.7% | 10/2 | −80.0% | p ≈ 1.000 | 5/1 | −80.0% | 1/0 | −100% | p ≈ 1.000 |

| Leukocyturia (pyuria) | 160/20 | −87.5% | 140/30 | −78.6% | p = 0.042 | 82/30 | −63.4% | 10/5 | −50.0% | p ≈ 0.552 |

| Change Category (Clinical Interpretation) | Mod ITT Pop at EOS (N = 362) | Discordant Result Pop at EOS Visit (N = 116) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR (n = 193) n (%) | C&S (n = 169) n (%) | p | PCR+/C− (n = 102) n (%) | PCR−/C+ (n = 14) n (%) | p | |

| Clinical failure subtotal (no change or addition) | 23/193 (11.9%) | 37/169 (21.9%) | p = 0.011 | 23/102 (22.5%) | 4/14 (28.6%) | p = 0.048 |

| Two additional symptoms (worse) | 1/193 (0.5%) | 8/169 (4.7%) | p ≈ 0.028 | 1/102 (1.0%) | 1/14 (7.1%) | p = 0.333 |

| One additional symptom (worse) | 2/193 (1.0%) | 10/169 (5.9%) | p ≈ 0.018 | 3/102 (2.9%) | 1/14 (7.1%) | p = 0.590 |

| No change (failure) | 20/193 (10.4%) | 19/169 (11.2%) | p = 0.806 | 19/102 (18.6%) | 2/14 (14.3%) | p = 1.000 |

| Favorable clinical outcome (≥1 symptom reduction) | 170/193 (88.1%) | 132/169 (78.1%) | p = 0.011) | 79/102 (77.5%) | 10/14 (71.4%) | p = 0.148 |

| One symptom reduction | 79/193 (40.9%) | 77/169 (45.5%) | p = 0.547 | 43/102 (42.2%) | 5/14 (35.7%) | p = 0.095 |

| Two symptoms reduced | 66/193 (34.2%) | 42/169 (24.8%) | p = 0.0311 | 20/102 (19.6%) | 3/14 (21.4%) | p = 0.654 |

| Three symptoms reduced | 23/193 (11.9%) | 11/169 (6.3%) | p = 0.047 | 14/102 (13.7%) | 2/14 (14.3%) | p = 1.000 |

| Four symptoms reduced | 2/193 (1.1%) | 2/169 (1.2%) | p = 0.763 | 2/102 (2.0%) | 0/14 (0.0%) | p = 1.000 |

| Total | 193 (100%) | 169 (100%) | — | 102 (100%) | 14 (100%) | — |

| Variable | PCR Arm (n = 193) | C&S Arm (n = 169) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-to-antibiotic start, h | 20 (IQR 12–36) | 52 (IQR 30–66) | <0.001 |

| Antibiotic appropriateness, n (%) | 161 (83.4%) | 105 (62.1%) | <0.001 |

| Metric | Mod ITT Pop at EOS (N = 362) | Discordant Result Pop at EOS Visit (N = 116) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR (n = 193) | C&S (n = 169) | p | PCR+/C− (n = 102) | PCR−/C+ (n = 14) | p | |

| % Complete clinical cure (no baseline symptoms at EOS) | 143/193 (74.1%) | 106/169 (62.7%) | p = 0.020 | 61/102 (59.8%) | 5/14 (35.7%) | p = 0.148 |

| % Partial cure (≥50% symptom reduction) | 159/193 (82.4%) | 121/169 (71.6%) | p = 0.014 | 68/102 (66.7%) | 8/14 (57.1%) | p = 0.553 |

| 100% symptom decrease with microbiological eradication (both clinical and culture) | 120/193 (62.2%) | 95/169 (56.2%) | p = 0.249 | 55/102 (53.9%) | 7/14 (50.0%) | p = 0.784 |

| 100% symptom decrease without microbiological eradication (clinical cure but culture persists) | 23/193 (11.9%) | 11/169 (6.5%) | p = 0.784 | 13/102 (12.7%) | 1/14 (7.1%) | p ≈ 1.000 |

| Predictor (Reference) | Model T: Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p (Model T) | Model M1: Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p (Model M1) | Model M2: Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p (Model M2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 65.79 (3.91–1108.08) | 0.0037 | 46.12 (2.90–733.7) | 0.0051 | 65.79 (3.91–1108.08) | 0.0037 |

| Diagnostic arm—PCR vs. C&S (C&S = ref) | 1.95 (1.12–3.39) | 0.018 | 1.67 (1.05–2.66) | 0.032 | 1.10 (0.33–3.71) | 0.880 |

| Time-to-antibiotic (per 1 h increase) | —(not in model) | — | 0.95 (0.926–0.975) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.926–0.975) | <0.001 |

| Antibiotic appropriateness (Yes vs. No) | —(not in model) | — | —(not in model) | — | 2.48 (1.45–4.24) | 0.001 |

| Any comorbidity (Yes vs. No) | 0.02 (0.004–0.089) | <0.000001 | 0.02 (0.004–0.089) | <0.000001 | 0.02 (0.004–0.089) | <0.000001 |

| Mono-infection vs. Polymicrobial (Poly = ref) | 3.49 (1.10–11.11) | 0.034 | 3.49 (1.10–11.11) | 0.034 | 3.49 (1.10–11.11) | 0.034 |

| Baseline symptoms—3 vs. 2 (ref = 2) | 0.083 (0.014–0.497) | 0.0064 | 0.083 (0.014–0.497) | 0.0064 | 0.083 (0.014–0.497) | 0.0064 |

| Baseline symptoms—4 vs. 2 | —(sparse) | 0.987 | —(sparse) | 0.987 | —(sparse) | 0.987 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kardjadj, M.; Priestly, I.P.; Chavez, R.; Derrick, D.; Huard, T.K. Clinical Symptom Resolution Following PCR-Guided vs. Culture and Susceptibility-Guided Management of Complicated UTI: How Time-To-Antibiotic Start and Antibiotic Appropriateness Mediate the Benefit of Multiplex PCR—An Ad Hoc Analysis of NCT06996301. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3107. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243107

Kardjadj M, Priestly IP, Chavez R, Derrick D, Huard TK. Clinical Symptom Resolution Following PCR-Guided vs. Culture and Susceptibility-Guided Management of Complicated UTI: How Time-To-Antibiotic Start and Antibiotic Appropriateness Mediate the Benefit of Multiplex PCR—An Ad Hoc Analysis of NCT06996301. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3107. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243107

Chicago/Turabian StyleKardjadj, Moustafa, Itoe P. Priestly, Roel Chavez, DeAndre Derrick, and Thomas K. Huard. 2025. "Clinical Symptom Resolution Following PCR-Guided vs. Culture and Susceptibility-Guided Management of Complicated UTI: How Time-To-Antibiotic Start and Antibiotic Appropriateness Mediate the Benefit of Multiplex PCR—An Ad Hoc Analysis of NCT06996301" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3107. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243107

APA StyleKardjadj, M., Priestly, I. P., Chavez, R., Derrick, D., & Huard, T. K. (2025). Clinical Symptom Resolution Following PCR-Guided vs. Culture and Susceptibility-Guided Management of Complicated UTI: How Time-To-Antibiotic Start and Antibiotic Appropriateness Mediate the Benefit of Multiplex PCR—An Ad Hoc Analysis of NCT06996301. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3107. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243107