Simultaneous Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement and Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair—The First Case in Serbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

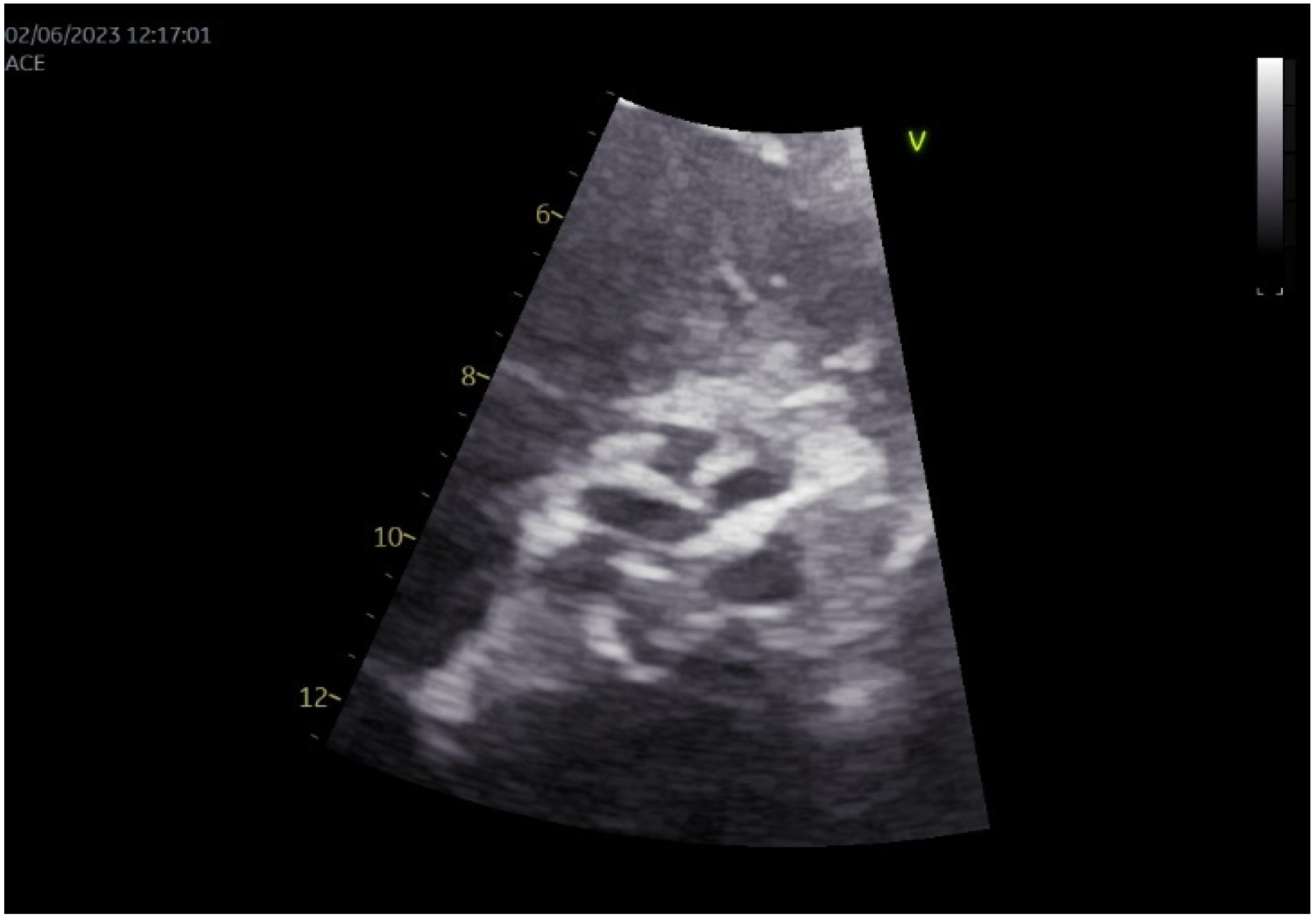

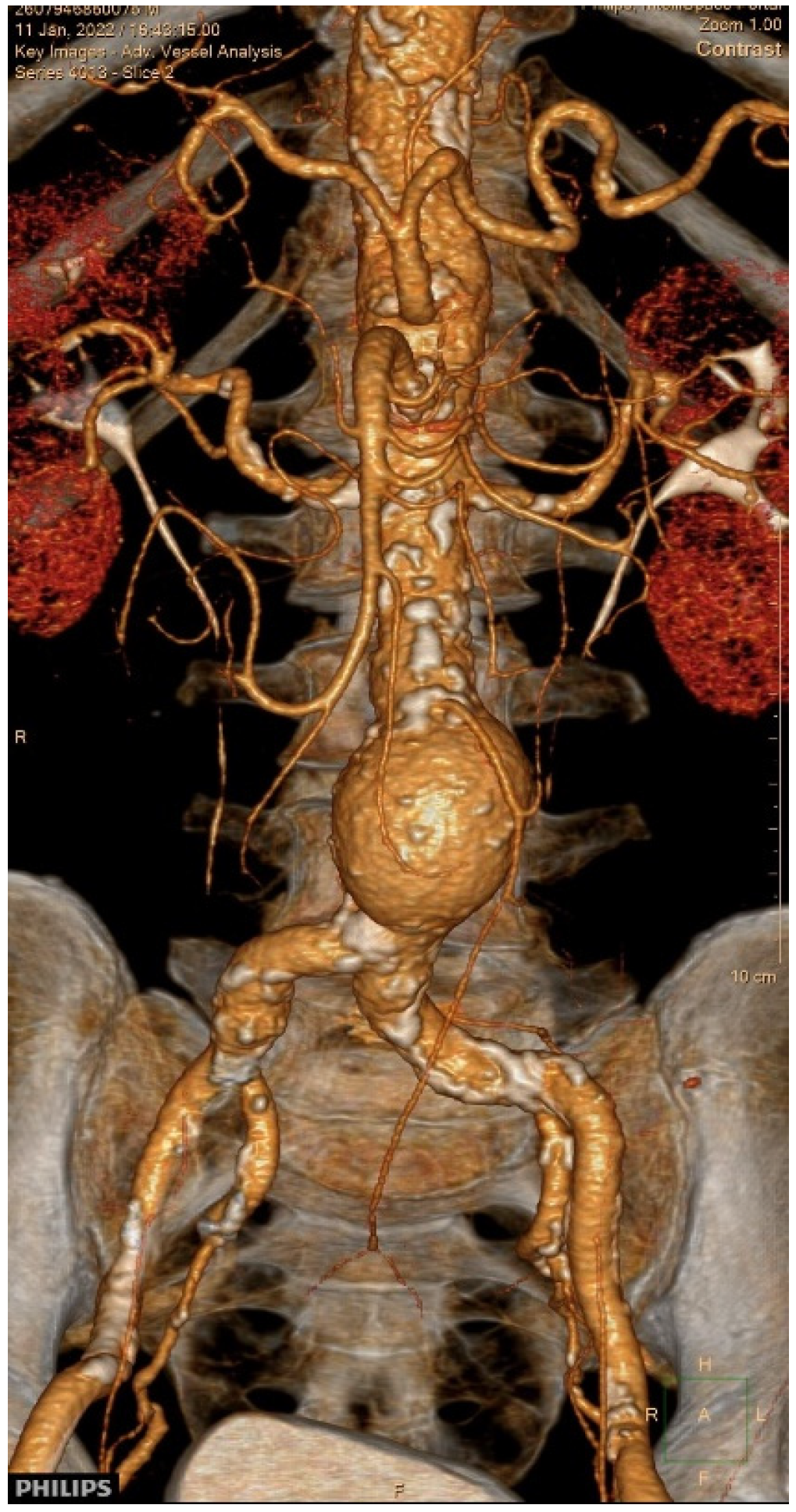

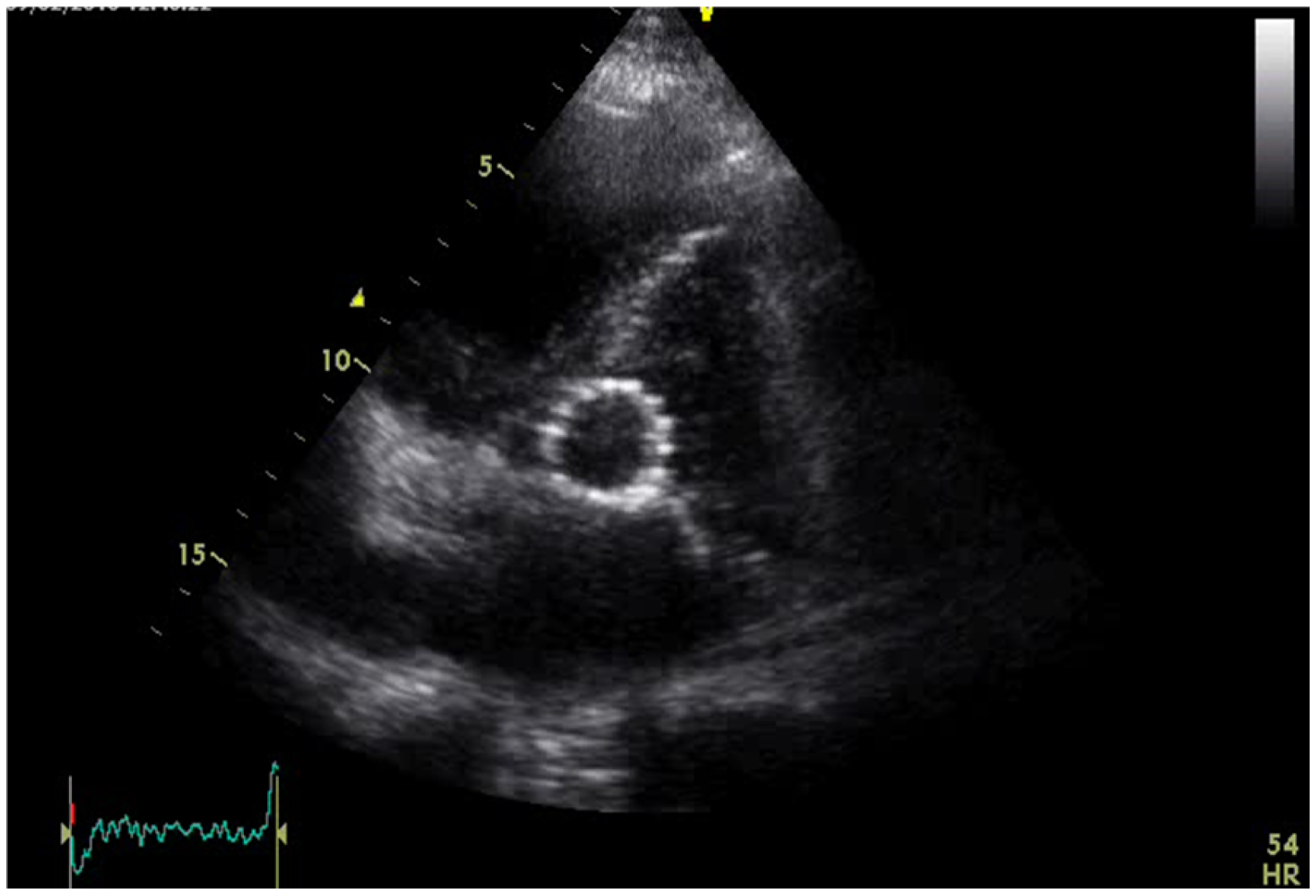

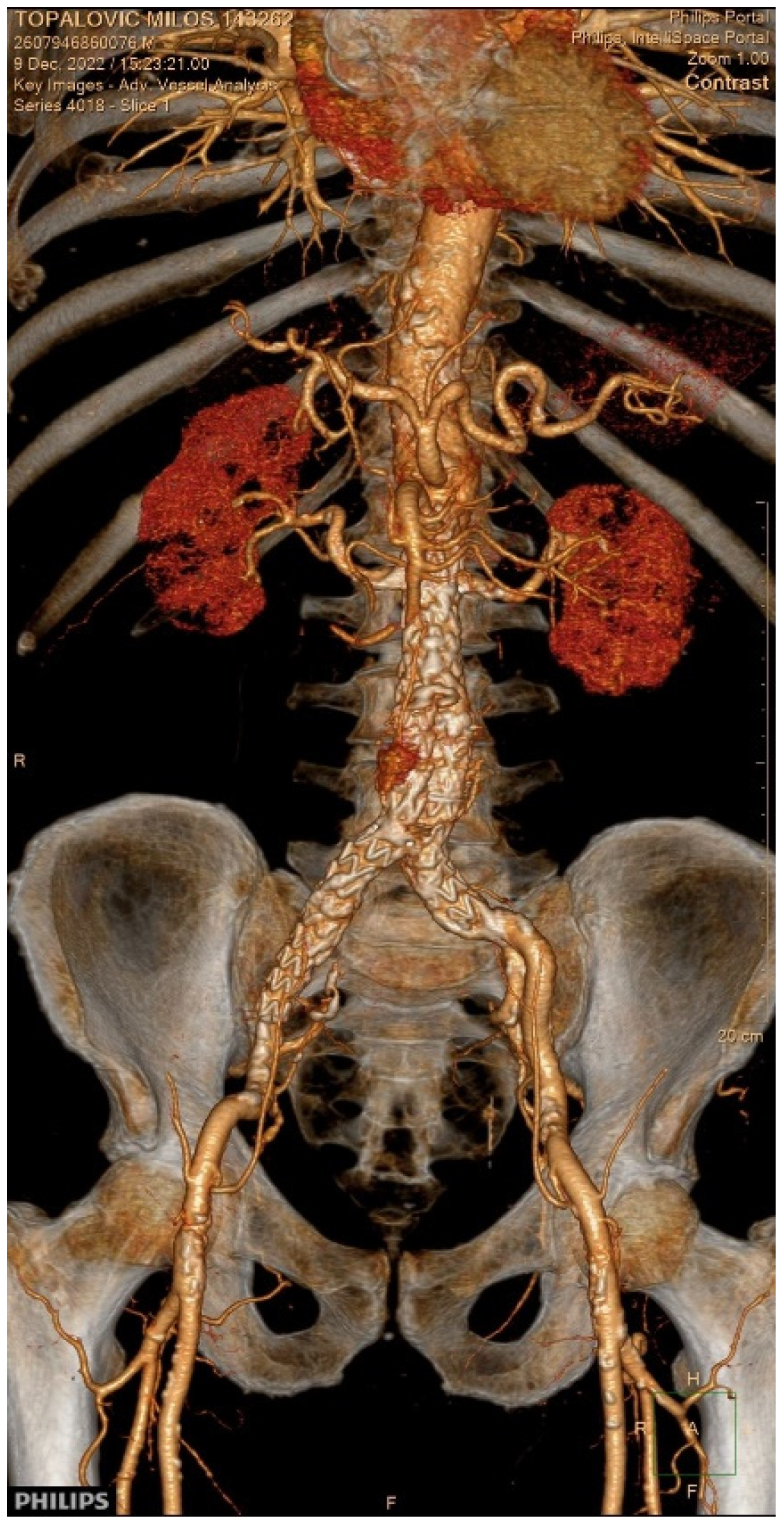

2. Case Presentation

3. Literature Review and Discussion

3.1. Search Strategy

3.2. Definition, Epidemiology, and Demographics

3.3. Justification for Combined Interventions, and Strategic Considerations in Procedural Sequencing

3.3.1. TAVR-First Strategy

3.3.2. EVAR-First Strategy

3.4. Procedural Sequencing and Complications

3.5. Post-Procedural Care

3.6. Prognosis and Follow-Up

3.6.1. Short-Term Outcomes

3.6.2. Long-Term Outcomes

3.7. Surveillance

3.8. Our Case

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Osnabrugge, R.L.; Mylotte, D.; Head, S.J.; Van Mieghem, N.M.; Nkomo, V.T.; LeReun, C.M.; Bogers, A.J.; Piazza, N.; Kappetein, A.P. Aortic stenosis in the elderly: Disease prevalence and number of candidates for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: A meta-analysis and modeling study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 1002–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmaljy, H.; Tawney, A.; Young, M. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement; StatPearls [Internet]: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jaegere, P.; Ronde, M.; Heijer, P.; Weger, A.; Baan, J. The history of transcatheter aortic valve implantation: The role and contribution of an early beliver and adopter, the Netherlands. Neth. Heart J. 2020, 28 (Suppl. S1), 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauri, S.; Bozzani, A.; Ferlini, M.; Aiello, M.; Gazzoli, F.; Pirrelli, S.; Valsecchi, F.; Ferrario, M. Combined Transcatheter Treatment of Severe Aortic Valve Stenosis and Infrarenal Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm in Increased Surgical Risk Patients. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 60, 480.e1–480.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsias, S.; Karaolanis, G.I.; Papafaklis, M.I.; Peroulis, M.; Tzimas, P.; Lakkas, L.; Mitsis, M.; Naka, K.K.; Michalis, L.K. Simultaneous Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation and Infrarenal Aortic Aneurysm Repair for Severe Aortic Stenosis and Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Report of 2 Cases and Literature Review. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020, 54, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harloff, M.T.; Percy, E.D.; Hirji, S.A.; Yazdchi, F.; Shim, H.; Chowdhury, M.; Malarczyk, A.A.; Sobieszczyk, P.S.; Sabe, A.A.; Shah, P.B.; et al. A step-by-step guide to trans-axillary transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020, 9, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, A.; Williams, R.M. Endovascular Aortic Aneursym Repair (EVAR). Ulster Med. J. 2013, 82, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Schizas, N.; Antonopoulous, C.N.; Patris, V.; Lampropoulous, K.; Kratimenos, T.; Argiriou, M. Current issues on simultaneous TAVR (Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement) and EVAR (Endovascular Aneurysm Repair). Clin. Case Rep. 2021, 9, e03929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medda, M.; Casilli, F.; Bande, M.; Glauber, M.; Tespili, M.; Cirri, S. Percutaneous treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm and aortic valve stenosis with ‘staged’ EVAR and TAVR: A case series. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2023, 18, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallitto, E.; Spath, P.; Faggioli, G.L.; Saia, F.; Palmerini, T.; Piazza, M.; D’Oria, M.; Simonte, G.; Cappiello, A.; Isernia, G.; et al. Simultaneous versus staged approach in transcatheter aortic valve implantation for severe stenosis and endovascular aortic repair for thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2024, 66, ezae379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, A.; Annabathula, R.V.; Allaham, H.; Chahal, D.; Toursavadkohi, S.; Gupta, A. In-Hospital Outcomes of Simultaneous and Staged Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement and Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Zaccarelli, M.; Testa, T.S.; Buscaglia, G.; Pratesi, G.; Crimi, G.; Balbi, M.; Di Gregorio, S.; Silvetti, S. Anesthetic Considerations in Combined TAVR and Aortic Endovascular Procedures, a Case Report. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2024, 27, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhaveri, K.D.; Saratzis, A.N.; Wanchoo, R.; Sarafidis, P.A. Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR)—A transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR)—Associated kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 1312–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drury-Smith, M.; Garnham, A.; Khogali, S. Sequential trans-catheter aortic valve implantation and abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2012, 79, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drury-Smith, M.; Garnham, A.; Khogali, S. Critical aortic stenosis in a patient with a large saccular abdominal aortic aneurysm: Simultaneous transcatheter aortic valve implantation and drive-by endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2012, 80, 1014–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh-Dastidar, M.; Dworakowski, R.; Lioupis, C.; Maccarthy, P.; Valenti, D.; El Gamel, A.; Monaghan, M.; Wendler, O. The combined treatment of aortic stenosis and abdominal aortic aneurysm using transcatheter tecniques: A case report. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 52, 895–898. [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi, Y.; Izumo, M.; Kusuhara, T.; Yokozuka, M.; Taketani, T.; Tanabe, K. Combined transcatheter aortic valve implantation and type II endoleak repair for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc. Interv. Ther. 2017, 32, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, H.; Watanabe, Y.; Kozuma, K. Successful transfemoral aortic valve implantation through aortic stent graft after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc. Interv. Ther. 2017, 32, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, B.R.; Greason, K.L.; Oderich, G.S.; Bresnahan, J.F.; Reeder, G.S.; Suri, R.M.; Mathew, V.; Rihal, C.S. Endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair to facilitate access for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 95, 1439–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluko, Y.; Diehl, L.; Jacoby, R.; Chan, B.; Andrews, S.; McMillan, E.; Sharkey, K.; Shook, P.; Ntim, W.; Bolorunduro, O.; et al. Simultaneous transcatheter aortic valve replacement and endovascular repair for critical aortic stenosis and large abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2015, 16, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, R.K.; Maisano, F.; Lachat, M. First report of simultaneous transcatheter aortic valve replacement, endovascular aortic aneurysm repair, and permanent pacemaker implantation after multi-vessel coronary stenting and left atrial appendage occlusion. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, F.; Cerillo, A.G.; Rizza, A.; Mariani, M.; De Caterina, A.R.; Palmieri, C.; Maffei, S.; Berti, S. Large abdominal aortic aneurysm in a high-risk surgical patient: Combined percutaneous transfemoral TAVI and EVAR procedure. J. Heart Valve Dis. 2015, 24, 310–312. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, Y.; Horiuchi, Y.; Yahagi, K.; Okuno, T.; Kusuhara, T.; Yokozuka, M.; Miura, S.; Taketani, T.; Tanabe, K. Simultaneous transcatheter aortic valve implantation and endovascular aneurysm repair in a patient with very severe aortic stenosis with abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Cardiol. Cases 2018, 17, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotzmann, M.; Hehen, T.; Germing, A.; Lindstaedt, M.; Yazar, A.; Laczkovics, A.; Mumme, A.; Mügge, A.; Bojara, W. Short term effects of transcatheter valve implantation on neurohormonal activation, quality of life and 6 min walk test in severe and symptomatic aortic stenosis. Heart 2010, 96, 1102–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, T.G.; Kalva, S.P.; Yeddula, K.; Wicky, S.; Kundu, S.; Drescher, P.; d’Othee, B.J.; Rose, S.C.; Cardella, J.F. Clinical practice guidelines for endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: Written by the Standards of Practice Committee for the Society of Interventional Radiology and endorsed by the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe and the Canadian Interventional Radiology Association. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2010, 21, 1632–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, R.A.; Otto, C.M.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin, J.P.; Fleisher, L.A.; Jneid, H.; Mack, M.J.; McLeod, C.J.; O’Gara, P.T.; et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2014, 129, 2440–2492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.; Kim, J.H.; Jeong, M.H. Minimally invasive transcatheter aortic valve replacement and sequential repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm in an octogenarian. Chonnam Med. J. 2021, 57, 228–229. [Google Scholar]

- Yammine, H.; Briggs, C.; Rolle, Q.; Ballast, J.; Frederick, J.; Skipper, E.; Downey, W.; Rinaldi, M.; Scherer, M.; Arko, F. Reemplazo transcatéter de válvula aórtica y reparación endovascular de aneurisma aórtico simultáneos. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 2156–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, J.; Tinoco, E.; Gallo, E.; Pereira, M.; Hipólito, L.; Silva, A. Severe aortic stenosis associated to large abdominal aortic aneurysm: Concomitant treatment with transcatheter aortic valve replacement and endovascular aneurysm repair. J. Transcatheter Interv. 2019, 27, eA201757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boljević, D.; Lakčević, J.; Farkić, M.; Mihajlović, V.; Veljković, S.; Šljivo, A.; Lukić, M.; Bojić, M.; Nikolić, A. Simultaneous Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement and Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair—The First Case in Serbia. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2785. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212785

Boljević D, Lakčević J, Farkić M, Mihajlović V, Veljković S, Šljivo A, Lukić M, Bojić M, Nikolić A. Simultaneous Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement and Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair—The First Case in Serbia. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(21):2785. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212785

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoljević, Darko, Jovana Lakčević, Mihajlo Farkić, Vladimir Mihajlović, Stefan Veljković, Armin Šljivo, Marina Lukić, Milovan Bojić, and Aleksandra Nikolić. 2025. "Simultaneous Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement and Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair—The First Case in Serbia" Diagnostics 15, no. 21: 2785. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212785

APA StyleBoljević, D., Lakčević, J., Farkić, M., Mihajlović, V., Veljković, S., Šljivo, A., Lukić, M., Bojić, M., & Nikolić, A. (2025). Simultaneous Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement and Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair—The First Case in Serbia. Diagnostics, 15(21), 2785. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212785