The Association of HER-2 Expression with Clinicopathological Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Localized Prostate Cancer After Radical Prostatectomy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Study Endpoints

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Variables

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Clinicopathologic Characteristics of the Entire Cohort

3.2. Sub-Cohorts Divided by Levels of HER-2 Protein Expression

3.3. Factors Associated with BCR and BCR-Free Survival

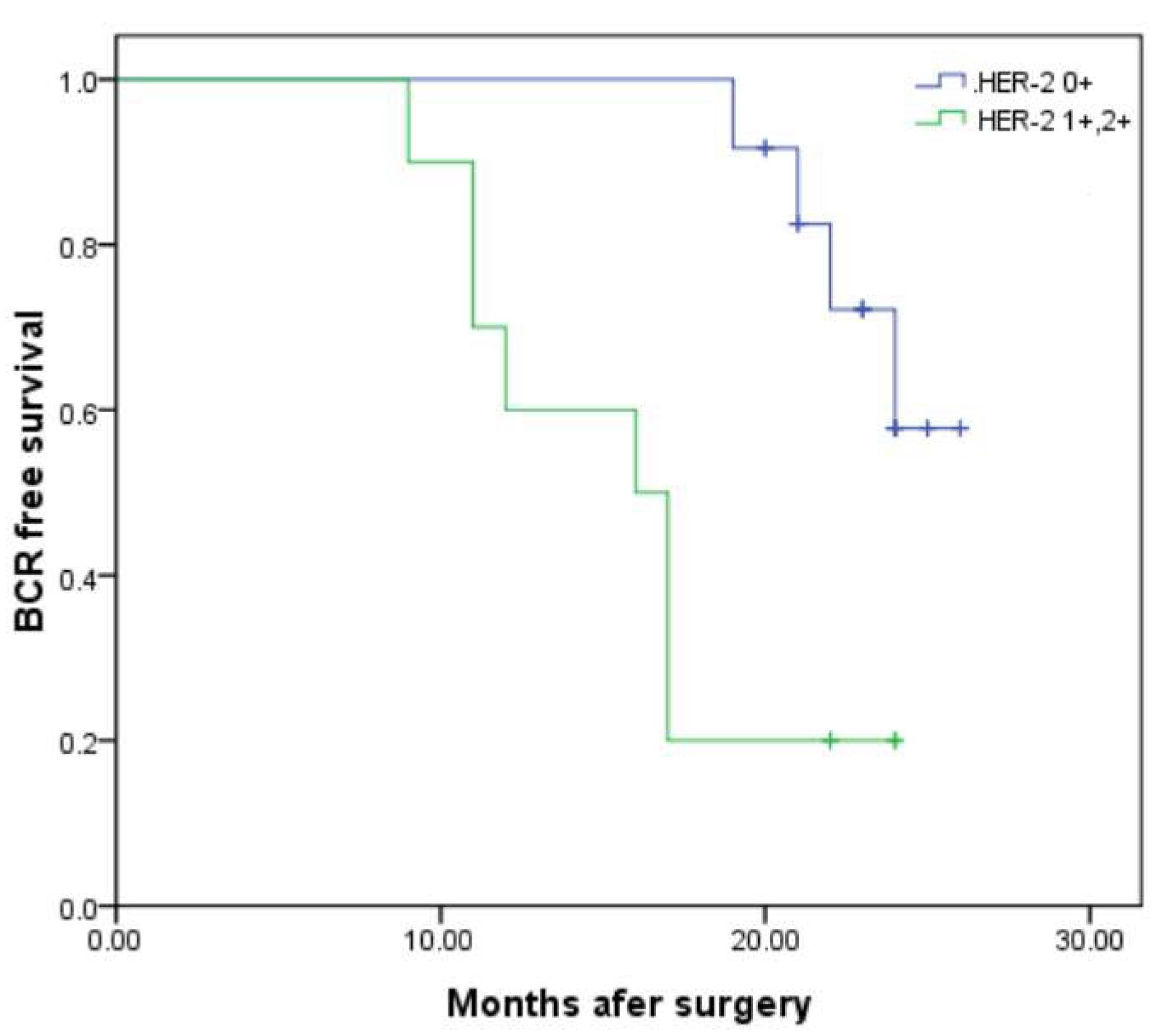

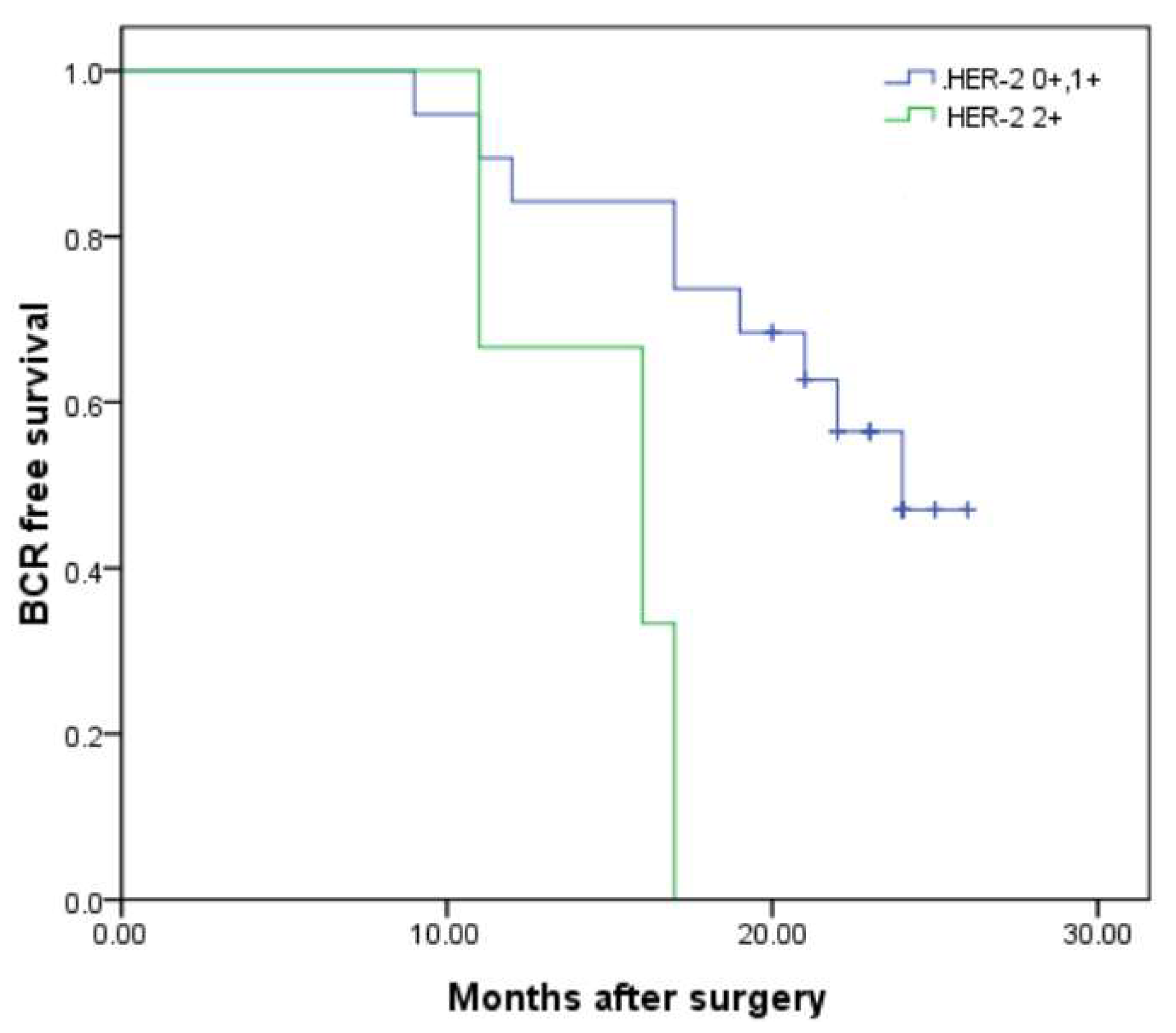

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informal Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ross, J.S.; Nazeer, T.; Church, K.; Amato, C.; Figge, H.; Rifkin, M.D.; Fisher, H.A.G. Contribution of HER-2/neu oncogene expression to tumor grade and DNA content analysis in the prediction of prostatic carcinoma metastasis. Cancer 1993, 72, 3020–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Press, M.F.; Bernstein, L.; Thomas, P.A.; Meisner, L.F.; Zhou, J.Y.; Ma, Y.; Hung, G.; Robinson, R.A.; Harris, C.; El-Naggar, A.; et al. HER-2/neu gene amplification characterized by fluorescence in situ hybridization: Poor prognosis in node-negative breast carcinomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 2894–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craft, N.; Shostak, Y.; Carey, M.; Sawyers, C.L. A mechanism for hormone independent prostate cancer through modulation of androgen receptor signaling by the HER-2/neu tyrosine kinase. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signoretti, S.; Montironi, R.; Manola, J.; Altimari, A.; Tam, C.; Bubley, G.; Balk, S.; Thomas, G.; Kaplan, I.; Hlatky, L.; et al. HER-2/neu expression and progression toward androgen independence in human prostate cancer. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000, 92, 1918–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, P.C.; Retik, A.B.; Vaughan, E.D. Anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy. In Campbell’s Urology, 8th ed.; Saunders (W. B. Saunders Co.): Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002; Volume 4, pp. 3107–3129. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, L.; Page, D.L.; Fleming, I.D. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- D’AMico, A.V.; Whittington, R.; Malkowicz, S.B.; Schultz, D.; Blank, K.; Broderick, G.A.; Tomaszewski, J.E.; Renshaw, A.A.; Kaplan, I.; Beard, C.J.; et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 1998, 280, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cookson, M.S.; Aus, G.; Burnett, A.L.; Canby-Hagino, E.D.; D’amico, A.V.; Dmochowski, R.R.; Eton, D.T.; Forman, J.D.; Goldenberg, S.L.; Hernandez, J.; et al. Variation in the definition of biochemical recurrence in patients treated for localized prostate cancer: The American Urological Association Prostate Guidelines for localized prostate update panel report and recommendations for a standard in the reporting of surgical outcomes. J. Urol. 2007, 177, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, I.; Scher, H.I.; Drobnjak, M.; Verbel, D.; Morris, M.; Agus, D.; Ross, J.S.; Cordon-Cardo, C. HER-2/neu (p185neu) protein expression in the natural or treated history of prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001, 7, 2643–2647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beerli, R.R.; Graus-Porta, D.; Woods-Cook, K.; Chen, X.; Yarden, Y.; Hynes, N.E. Neu differentiation factor activation of erbB-3 and erbB-4 is cell specific and displays a differential requirement for erbB-2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995, 15, 6496–6505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rink, M.; Chun, F.K.; Dahlem, R.; Soave, A.; Minner, S.; Hansen, J.; Stoupiec, M.; Coith, C.; Kluth, L.A.; Ahyai, S.A.; et al. Prognostic role and HER-2 expression of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood of patients prior to radical cystectomy: A prospective study. Eur. Urol. 2012, 61, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldscholte, J.; Berrevoets, C.; Ris-Stalpers, C.; Kuiper, G.; Jenster, G.; Trapman, J.; Brinkmann, A.; Mulder, E. The androgen receptor in LNCaP cells contains a mutation in the ligand binding domain which affects steroid binding characteristics and response to antiandrogens. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1992, 41, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, R.; Lin, D.; Nieto, M.; Sicinska, E.; Garraway, L.A.; Adams, H.; Signoretti, S.; Hahn, W.C.; Loda, M. Androgen dependent regulation of HER-2/neu in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 5723–5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardelli, C.; Jackson, M.W.; Choong, C.S.; Stahl, J.; Marshall, V.R.; Horsfall, D.J.; Tilley, W.D. Elevated level s of HER-2/neu and androgen receptor in clinically localized prostate cancer identifies metastatic potential. Prostate 2008, 68, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeppen, H.K.W.; Wright, B.D.; Burt, A.D.; Quirke, P.; McNicol, A.M.; Dybdal, N.O.; Sliwkowski, M.X.; Hillan, K.J. Overexpression of HER2/neu in solid tumours: An immunohistochemical survey. Histopathology 2001, 38, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, P.N., Jr.; Longmate, J.; Ruel, C.; Chee, K.G.; Longmate, J.; Ruel, C.; Meyers, F.J.; Gray, C.R.; Edwards, R.G.; Gumerlock, P.H.; et al. Trastuzumab plus docetaxel in HER-2/neu positive prostate carcinoma: Final results from the California Cancer Consortium Screening and Phase II trial. Cancer 2004, 100, 2125–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Aoki, S.; Tobiume, M.; Zennami, K.; Kato, Y.; Nishikawa, G.; Yoshizawa, T.; Itoh, Y.; Nakaoka, A.; et al. Lactate dehydrogenase, Gleason Score and HER-2 overexpression are significant prognostic factors for M1b prostate cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2011, 25, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Murray, N.P.; Badinez, L.V.; Dueñas, R.; Orellana, N.; Tapia, P. Positive HER-2 protein expression in circulating prostate cells and micro-metastasis, resistant to androgen blockage but not diethylstilbestol. Indian J. Urol. 2011, 27, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shariat, S.F.; Bensalah, K.; Karam, J.A.; Roehrborn, C.G.; Gallina, A.; Lotan, Y.; Slawin, K.M.; Karakiewicz, P.I. Preoperative plasma HER2 and epidermal growth factor receptor for staging and prognostication in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 15, 5377–5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Petrylak, D.P.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Chatta, K.; Fleming, M.T.; Smith, D.C.; Appleman, L.J.; Hussain, A.; Modiano, M.; Singh, P.; Tagawa, S.T.; et al. PSMA ADC monotherapy in patients with progressive metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer following abiraterone and/or enzalutamide: Efficacy and safety in open-label single arm phase 2 study. Prostate 2020, 80, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milowsky, M.I.; Galsky, M.D.; Morris, M.J.; Crona, D.J.; George, D.J.; Dreicer, R.; Tse, K.; Petruck, J.; Webb, I.J.; Bander, N.H.; et al. Phase 1/2 multiple ascending dose trial of the prostate specific cancer. Urol. Oncol. 2016, 34, 530.e15–530.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Entire Cohort | Cohort-1 (HER-2 0) | Cohort-2 (HER-2 1+, 2+) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 44 | 24 | 20 | |

| Age (years) | 67.95 ± 6.89 | 68.33 ± 7.70 | 67.5 ± 5.93 | 0.694 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.60 ± 2.13 | 25.51 ± 2.25 | 25.70 ± 2.02 | 0.771 |

| tPSA (ng/mL) | 29.49 ± 40.59 | 36.66 ± 51.68 | 20.89 ± 18.80 | 0.203 |

| f/t | 0.129 ± 0.01 | 0.119 ± 0.047 | 0.148 ± 0.046 | 0.177 |

| TPV (mL) | 34.77 ± 12.28 | 32.82 ± 11.09 | 37.11 ± 13.48 | 0.254 |

| BCP (%) | 44.65 ± 22.48 | 49.03 ± 17.91 | 39.01 ± 26.93 | 0.216 |

| GS (n, %) | 0.40 | |||

| ≤6 | 2 (4.5) | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0) | |

| 7 | 22 (50) | 12 (50) | 10 (50) | |

| ≥8 | 20 (45.45) | 10 (41.7) | 10 (50) | |

| pT stage (n, %) | 0.911 | |||

| pT2 | 26 (59.09) | 14 (58.3) | 12 (60) | |

| pT3 | 18 (40.91) | 10 (41.7) | 8 (40) | |

| PSM (n, %) | 19 (43.18) | 6 (25) | 13 (65) | 0.008 |

| Cohort-3 | Cohort-4 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (HER-2 0, 1+) | (HER-2 2+) | ||

| Number | 38 | 6 | |

| Age (years) | 67.79 ± 7.14 | 69.00 ± 5.44 | 0.694 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.53 ± 2.12 | 26.04 ± 2.34 | 0.588 |

| tPSA (ng/mL) | 31.25 ± 43.36 | 12.46 ± 0.50 | 0.299 |

| f/t | 0.129 ± 0.048 | 0.113 ± 0.069 | 0.521 |

| TPV (mL) | 32.72 ± 11.57 | 43.73 ± 8.49 | 0.004 |

| BCP (%) | 49.84 ± 18.86 | 29.37 ± 32.58 | 0.043 |

| GS (n, %) | 0.499 | ||

| ≤6 | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0) | |

| 7 | 20 (52.6) | 2 (33.3) | |

| ≥8 | 16 (42.1) | 4 (66.7) | |

| pT stage (n, %) | 1 | ||

| pT2 | 22 (57.9) | 4 (66.7) | |

| pT3 | 16 (42.1) | 2 (33.3) | |

| PSM (n, %) | 15 (39.47) | 4 (66.7) | 0.211 |

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSM vs. NSM | PSM vs. NSM | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| HER-2 0 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| HER-2 1+, 2+ | 2.333 | 0.897–6.072 | 0.046 | 2.691 | 0.619–11.71 | 0.042 |

| HER-2 0, 1+ | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| HER-2 2+ | 1.25 | 0.625–11.233 | 0.082 | 2.667 | 0.298–23.858 | 0.380 |

| No BCR 26 | BCR 18 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HER-2 0 (n, %) | 18 (75) | 6 (25) | 0.019 |

| HER-2 1+, 2+ | 8 (40) | 12 (60) | |

| HER-2 0, 1+ (n, %) | 25 (65.79) | 13 (34.21) | 0.023 |

| HER-2 2+ | 1 (16.67) | 5 (83.33) | |

| GS (n, %) | 0.151 | ||

| ≤6 | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| 7 | 15 (50) | 7 (50) | |

| ≥8 | 9 (40) | 11 (50) | |

| pT stage (n, %) | 0.100 | ||

| pT2 | 18 (69.23) | 8 (30.77) | |

| pT3 | 8 (44.44) | 10 (55.56) | |

| PSM (n, %) | 7 (36.84) | 12 (63.16) | 0.009 |

| NSM (n, %) | 19 (76) | 6 (24) |

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| HER-2 0 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| HER-2 1+, 2+ | 4 | 1.337–11.965 | 0.005 | 17.002 | 1.378–210.216 | <0.001 |

| HER-2 0, 1+ | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| HER-2 2+ | 1.615 | 0.825–2.424 | 0.015 | 2.849 | 1.234–3.246 | 0.004 |

| GS | ||||||

| ≤6 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| 7 | 1.5 | 0.613–3.670 | 0.374 | 8.745 | 0.535–2.822 | 0.151 |

| ≥8 | 1.25 | 0.493–3.167 | 0.638 | 5.441 | 0.789–2.632 | 0.452 |

| Surgical margin | ||||||

| NSM | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| PSM | 6.5 | 3.377–12.51 | 0.006 | 6.118 | 3.083–11.72 | 0.007 |

| pT stage | ||||||

| T2 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| T3 | 1.167 | 0.540–2.522 | 0.334 | 17.022 | 0.678–2.216 | 0.327 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; You, R.; Yang, X.; Du, P.; Liu, Y.; Ji, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Cao, Y.; Ma, J.; Yang, Y. The Association of HER-2 Expression with Clinicopathological Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Localized Prostate Cancer After Radical Prostatectomy. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2717. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212717

Wang S, You R, Yang X, Du P, Liu Y, Ji Y, Zhao Q, Cao Y, Ma J, Yang Y. The Association of HER-2 Expression with Clinicopathological Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Localized Prostate Cancer After Radical Prostatectomy. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(21):2717. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212717

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shuo, Ruijian You, Xiao Yang, Peng Du, Yiqiang Liu, Yongpeng Ji, Qiang Zhao, Yudong Cao, Jinchao Ma, and Yong Yang. 2025. "The Association of HER-2 Expression with Clinicopathological Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Localized Prostate Cancer After Radical Prostatectomy" Diagnostics 15, no. 21: 2717. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212717

APA StyleWang, S., You, R., Yang, X., Du, P., Liu, Y., Ji, Y., Zhao, Q., Cao, Y., Ma, J., & Yang, Y. (2025). The Association of HER-2 Expression with Clinicopathological Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Localized Prostate Cancer After Radical Prostatectomy. Diagnostics, 15(21), 2717. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15212717